Jeremy Butterfield's Blog, page 29

November 5, 2014

averse to adverse to: 20 words not to confuse (9-10)

1. Takeaways – in a nutshell

Using “to be adverse to something” to mean “to dislike something” is considered a mistake by many people, dictionaries, and usage guides.

It has been suggested that this use may be more common in American English than in British English.

Beware of incorrectly using x averse in phrases such as “to have an adverse reaction to something”.

Conversely, beware of using adverse in compound adjectives formed with averse: risk-averse, not x risk-adverse.

2. In detail

2.1 Averse

How many times have you seen sentences such as “He was not adverse to compromising himself politically for the sake of his career” or “Are Scottish people adverse to a little sex in their movies?”

They seem to confuse two words that are almost identically spelled but have rather different meanings.

The standard construction to suggest that a person has a strong dislike of or antipathy towards something is averse to, often used with negation:

Examples (from Oxford Dictionary Online)

• Strong and aggressive, he is not averse to a bit of shirt pulling and uses his arms effectively to hold off defenders.

• Now some of you may know that if an opportunity arises of a little fun with a person of the opposite sex I’m not averse, rare as it is.

• I also stand to see the value of my property increase, which I’m not averse to.

• I am a recent alumna of the University of Waterloo and do not consider myself in any way averse to liberal writing.

• I’ve noticed I’m becoming more and more averse to what I call overt luxury.

As in all but one of the examples above-and note how most of them are first person statements-, averse in negative contexts is often a form of ironic understatement, or litotes: “I’m not averse to” means something like “I’m really rather keen on” (though perhaps reluctant to admit it). All the examples above also show averse being used in the structure to be averse to, i.e. predicatively.

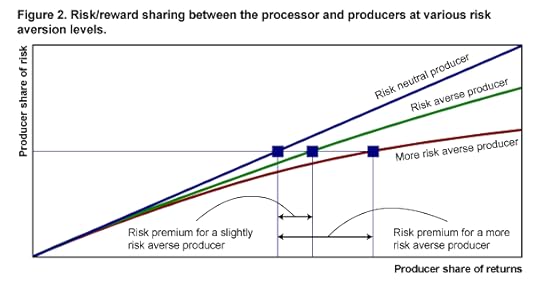

Averse is also often used as the second part of a compound adjective, such as risk-averse, change-averse and so forth.  Occasionally NOUN-adverse is wrongly used, as in this article on the use of “guys”.

Occasionally NOUN-adverse is wrongly used, as in this article on the use of “guys”.

2.2 Adverse

Adverse, broadly speaking, means: “unfavourable” (an adverse balance of trade, adverse circumstances, adverse weather conditions); “hostile” (adverse criticism, an adverse reaction); or “harmful” (adverse effects)

Examples (from Oxford Dictionary Online/Oxford English Corpus)

• From 1997 to 2000, the combination of adverse weather and declining sales led to retrenchment by any cooperatives.

• A series of meetings at the department after the leak of cabinet papers and the widespread adverse reaction to the government’s plans has led ministers to slow the process.

• Such events promote Belfast’s image and go some considerable way to countering the adverse publicity the city has often received over the years.

• The trials had been cancelled after the drug was found to cause an adverse reaction.

• Roadworks on three of the routes in and out of Skipton are having an adverse effect on local businesses.

In contrast to averse, in these examples adverse modifies a following noun (in other words, it is attributive).

3. Can the word’s origins help?

Without falling into the etymological fallacy, (the notion that a word’s original meaning, or its meaning in the language from which it derives, is its only true meaning) examining these two words’ origins may help clarify the distinction between them.

Both come from Latin, and contain the Latin verb vertere, “to turn”, found in so many other verbs and adjectives, (convert, divert, extrovert, invert, pervert, etc).

The late 16th century averse comes from Latin aversus ”turned away from”, past participle of avertere. The a- part gives it the meaning “away from”. The old-fashioned phrase “avert your gaze” means “turn your gaze away”, in other words “look away”. Remembering that, and the related noun aversion, may help to crystallize the distinction.

In contrast, adverse from Latin adversus “against, opposite”, suggests the notion of one thing being in opposition to another, and therefore hostile or unfavourable to it. Its related noun is adversity, a synonym for misfortune or difficulty.

4. adverse to: a complication

To be adverse to mirrors averse to structurally in certain phrases, particularly in legal contexts, e.g. “…‘adverse party’ includes every party whose interest on the case is adverse to the interests of the appellant…”–Wisconsin Statutes, 1947; “…the whole parliamentary tradition as built up in this country…is adverse to it“–Winston Churchill, 1942. But in this meaning it refers to things, to external circumstances, whereas, as we have seen, averse to refers to someone’s personal tastes and inclinations.

5. What do usage guides say?

The Oxford Dictionary Online has a note that calls e.g. “He is not adverse to making a profit” a mistake. The AP Style Guide and the British Guardian Style Guide draw an absolute distinction between the two words, as does Fowler.  Merriam-Webster’s Concise English Usage has a long, scholarly, slightly non-committal discussion pointing to potential overlaps between the two words. The grammar checker in Microsoft’s Word will flag up “not adverse to” as a mistake-which is helpful for many people, but could cause problems for those–often, but not necessarily, lawyers–who are using it correctly.

Merriam-Webster’s Concise English Usage has a long, scholarly, slightly non-committal discussion pointing to potential overlaps between the two words. The grammar checker in Microsoft’s Word will flag up “not adverse to” as a mistake-which is helpful for many people, but could cause problems for those–often, but not necessarily, lawyers–who are using it correctly.

A quick scan of Google Ngrams for “not averse to” and “not adverse to” suggests that while “not adverse to” was previously often confined to legal contexts of the kind mentioned at 4. above, recent decades show an increase in its use as a substitute for the preferred “not averse to”.

In the Oxford English Corpus, a simple search for “adverse to” shows that in British English 60 per cent of examples are in legal contexts, and therefore assumed to be correct, but in American English that figure is less than 1 per cent.

However, it cannot automatically be inferred that the use of the phrase in non-legal contexts is wrong. In fact, in AmE only one third of those non-legal uses were of the criticized use, while in BrE it was over two thirds. If one compares the number of times averse to was actually used with approximate estimates of how often adverse to was used for it by mistake, the figures are as follows: BrE 730/92; AmE 662/81 giving ratios of around 8:1 for both. This evidence does not suggest that the mistake is more frequent in AmE than in BrE.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Fowler's Modern English Usage, Grammar, Meaning of words, Oxford Online Dictionary, Writing Skills Tagged: 20 confusable words

October 30, 2014

Business Writing Skills: some tips for catchy headlines

In my previous blog on headings, I suggested that headings perform several crucial functions.

1. whetting readers’ curiosity;

2. providing sound bites of your topics;

3. helping readers home in on what is relevant to them;

4. helping you plan and structure what you write.

Today I would like to analyse the first two.

Whetting readers’ curiosity.

Your first task as a business writer is to motivate people to read what you have written. Their hearts may sink at the sight of yet another document, so it is your job to overcome their reluctance. Here are some thoughts on how to do just that.

Take a tip from journalists.

First, grab attention.

Journalists are great at creating headlines and summaries that grab the attention of readers, viewers and listeners. They do it not only in newspapers and online news, but also on TV and radio. Granted, in a serious business report it is not appropriate to use tabloid style headlines. But you can still use headings that are interesting rather than bland.

Some examples.

Here are three news headlines picked at random (on 28 November 2012).

‘You can photograph nudes anywhere’. (Yahoo news)

Intriguing, isn’t it? It makes you want to find out more. You sense there’s a saucy story behind these five words. (The item is about the Pirelli 2013 Calendar.)

‘UK rivers remain on flood watch’. (Guardian)

Very matter of fact, but it alerts people who could be affected to find out more.

‘One in ten workers underemployed.’ (BBC News)

Lays out the whole story in five words. If you go to the article, you find that the heading is slightly different: Underemployment affects 10.5% of UK workforce. Notice how the headline puts the figures in a way that people can understand at first glance, rather than as a percentage.

I can’t do that in business writing!

You may not be used to it, but why not try it? Here are six tips.

1. Use questions.

They engage the reader. Instead of the bland and uninformative “Current market situation” how about “Where is the market heading?“, “What’s new in the market?“, “Can the market grow any more?” and so on.

2. Create a picture.

People visualize as they read. Help them do that by suggesting an image. Like the Pirelli Calendar above.

3. Keep headings short.

Five to seven words is about right, as in the news headlines above.

4. Zap unnecessary words.

Use newspaper headline style to get rid of words such as “the” and “a”.

“The court rules in Bonzo’s favour” becomes “Court rules in Bonzo’s favour“.

5. More than one headline per page.

Exactly how many depends on what you are writing about. A single-page memo could have three or four.

6.Help people understand figures at a glance.

The BBC example above shows one way of doing this.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Business Writing Skills, Writing Skills Tagged: Catchy headlines

October 27, 2014

Voracious or veracious readers? 20 words not to confuse (7-8)

I’ve seen a few profiles on Twitter of people who call themselves “veracious readers“. Presumably they mean “voracious readers“. If so, their self-styled title is deeply ironic: even if they read a lot, they cannot be very attentive to the spelling of their reading matter.

I’ve seen a few profiles on Twitter of people who call themselves “veracious readers“. Presumably they mean “voracious readers“. If so, their self-styled title is deeply ironic: even if they read a lot, they cannot be very attentive to the spelling of their reading matter.

Voracious refers to people who eat a lot, and then, as a metaphor, to people who engage in an activity with great gusto and enthusiasm.  At several removes, it’s related to the verb devour, since both derive from Latin vorāre.

At several removes, it’s related to the verb devour, since both derive from Latin vorāre.

Veracious, in contrast, is a really rather rare word, meaning “truthful”, e.g. a veracious witness to great and grave events. So, a “veracious reader” would be a truthful one, though I doubt that is the claim people describing themselves as such are making. Like voracious, it too derives ultimately from Latin, from the word for “true”, vērus, which has given us words such as verify, verity, and the vera of Aloe vera.

Veracious is also used by mistake in phrases such as *veracious appetite instead of the correct voracious appetite.

Of course, veracious may be just a homophone typo for voracious. What I mean is that it is fatally easy to have two words in your mental lexicon that sound exactly the same, and to key one instead of the other, such as “two” for “too“. You know the difference, but when you type with only half a mind on what you’re doing, the wrong one takes over.

In case you’re not convinced that the two words sound the same, here is the phonetic spelling of voracious /vəˈreɪʃəs/, and here it is for veracious: /vəˈreɪʃəs/. Identical. The villain of the piece is that tricksy little symbol /ə/, which occurs in the first and last syllables. It represents the “uh” sound known as a “schwa“, which is responsible for a huge number of spelling mistakes in English.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Grammar, Meaning of words, Spelling, Writing Skills Tagged: 20 confusable words

October 17, 2014

Flaunting or flouting the law? 20 words not to confuse (5-6)

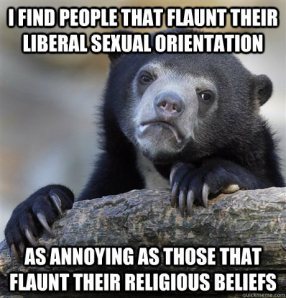

Put simply, it is this: Are people who write sentences such as “motorists who blatantly flaunt the regulations for their safety and well-being” (instead of flout) woefully ignorant dunderheads who need remedial English and should not be allowed into print, or are they just following a long-standing and perfectly legitimate linguistic trend?

How you answer that question defines your place on the descriptive-prescriptive spectrum (if you answer “yes”, you are probably an out-and-out prescriptivist). Your answer may also depend on where you live, and which dictionary or usage guide you take as your bible.

what do these words mean?

Though sounding similar, they have—at least in origin—very different meanings. If you flaunt something, you show it off in a way which is brash and overdone. The very use of the word suggests that  you don’t approve of whoever is doing the flaunting. Typical things that people flaunt are their wealth, their sexuality, and themselves.

you don’t approve of whoever is doing the flaunting. Typical things that people flaunt are their wealth, their sexuality, and themselves.

He flaunts his riches like everyone in the business.

Women should have it both ways—they should be able to flaunt their sexuality and be taken seriously.

Katie seemed to be flaunting herself a little too much for Elizabeth’s liking.

If you flout a law, rule, regulation, convention, and semantically related nouns, you do not obey them, and treat them with blatant disregard.

Around 10 smokers were openly flouting the ban when the Health Board’s environmental health inspectors arrived.

A quote from Chinua Achebe (1987) illustrates the confusion between the two. “Your Excellency, let us not flaunt the wishes of the people.” “Flout, you mean,” I said. “The people?” asked His Excellency, ignoring my piece of pedantry.

WHAT DO DICTIONARIES AND USAGE GUIDES SAY?

Merriam-Webster gives that transitive use of flaunt two definitions.

1 to display ostentatiously or impudently:

2 to treat contemptuously

while adding a note, which states that the use of flaunt in this way “undoubtedly arose from confusion with flout”, but that the contexts in which it appears cannot be considered “substandard”. Yet it hedges its bets by stating that “many people will consider it a mistake”.

On the other side of the pond, Oxford Dictionaries Online (ODO) states categorically that the two words “may sound similar but they have different meanings”.  The 1993 draft addition to the OED entry notes that the usage “clearly arose by confusion, and is widely considered erroneous”.

The 1993 draft addition to the OED entry notes that the usage “clearly arose by confusion, and is widely considered erroneous”.

Various British usage guides maintain the distinction rigidly, and the Economist style guide’s witty note runs “Flaunt means display; flout means disdain. If you flout this distinction, you will flaunt your ignorance”. The Australian Macquarie dictionary notes “Flaunt is commonly confused with flout”.

Nevertheless, ODO admits that in the Oxford English Corpus (OEC) “the second and third commonest objects of flaunt, after wealth, are law and rules”.

While that is true, closer inspection reveals that the “correct” flout the law, flout the rules, are several times more frequent, and this is borne out by the Corpus of Contemporary American. So, while Merriam-Webster is less prescriptive than Oxford, Macquarie, and British style guides, in that it accepts the “wrong” use, these figures suggest that many more people actually maintain the distinction than ignore it.

Furthermore, only a very small percentage of examples of flaunt in the OEC show it being used to mean “flout”.

Conclusion

Given the current state of things, any reply to my original question has to be nuanced. So, if you read something that contains collocations such as flaunt…rules, regulations, convention, you could try to suppress a sigh for the total collapse and degradation of the English language and just give the writer the benefit of the doubt: it is presumably part of his or her idiolect.

Flaunt has been used to mean “flout” since the 1920s, according to the draft addition to the OED entry, and appears regularly, particularly in journalistic writing. At least one dictionary recognizes it as having that meaning; in the long run, others may accept it too.

On the other hand, if you are writing or editing something, there is an argument that it would be wise to maintain the distinction. In that way, you will avoid the involuntary sighs of many of your readers as they are distracted from the content of your message by what they see as a flaw in its form.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Grammar, Meaning of words, OED, Oxford Online Dictionary, Writing Skills Tagged: 20 confusable words

Flaunting the law or flouting the law? 20 words not to confuse (5-6)

Put simply, it is this: Are people who write sentences such as “motorists who blatantly flaunt the regulations for their safety and well-being” (instead of flout) woefully ignorant dunderheads who need remedial English and should not be allowed into print, or are they just following a long-standing and perfectly legitimate linguistic trend?

How you answer that question defines your place on the descriptive-prescriptive spectrum (if you answer “yes”, you are probably an out-and-out prescriptivist). Your answer may also depend on where you live, and which dictionary or usage guide you take as your bible.

what do these words mean?

Though sounding similar, they have—at least in origin—very different meanings. If you flaunt something, you show it off in a way which is brash and overdone. The very use of the word suggests that  you don’t approve of whoever is doing the flaunting. Typical things that people flaunt are their wealth, their sexuality, and themselves.

you don’t approve of whoever is doing the flaunting. Typical things that people flaunt are their wealth, their sexuality, and themselves.

He flaunts his riches like everyone in the business.

Women should have it both ways—they should be able to flaunt their sexuality and be taken seriously.

Katie seemed to be flaunting herself a little too much for Elizabeth’s liking.

If you flout a law, rule, regulation, convention, and semantically related nouns, you do not obey them, and treat them with blatant disregard.

Around 10 smokers were openly flouting the ban when the Health Board’s environmental health inspectors arrived.

A quote from Chinua Achebe (1987) illustrates the confusion between the two. “Your Excellency, let us not flaunt the wishes of the people.” “Flout, you mean,” I said. “The people?” asked His Excellency, ignoring my piece of pedantry.

WHAT DO DICTIONARIES AND USAGE GUIDES SAY?

Merriam-Webster gives that transitive use of flaunt two definitions.

1 to display ostentatiously or impudently:

2 to treat contemptuously

while adding a note, which states that the use of flaunt in this way “undoubtedly arose from confusion with flout”, but that the contexts in which it appears cannot be considered “substandard”. Yet it hedges its bets by stating that “many people will consider it a mistake”.

On the other side of the pond, Oxford Dictionaries Online (ODO) states categorically that the two words “may sound similar but they have different meanings”.  The 1993 draft addition to the OED entry notes that the usage “clearly arose by confusion, and is widely considered erroneous”.

The 1993 draft addition to the OED entry notes that the usage “clearly arose by confusion, and is widely considered erroneous”.

Various British usage guides maintain the distinction rigidly, and the Economist style guide’s witty note runs “Flaunt means display; flout means disdain. If you flout this distinction, you will flaunt your ignorance”. The Australian Macquarie dictionary notes “Flaunt is commonly confused with flout”.

Nevertheless, ODO admits that in the Oxford English Corpus (OEC) “the second and third commonest objects of flaunt, after wealth, are law and rules”.

While that is true, closer inspection reveals that the “correct” flout the law, flout the rules, are several times more frequent, and this is borne out by the Corpus of Contemporary American. So, while Merriam-Webster is less prescriptive than Oxford, Macquarie, and British style guides, in that it accepts the “wrong” use, these figures suggest that many more people actually maintain the distinction than ignore it.

Furthermore, only a very small percentage of examples of flaunt in the OEC show it being used to mean “flout”.

Conclusion

Given the current state of things, any reply to my original question has to be nuanced. So, if you read something that contains collocations such as flaunt…rules, regulations, convention, you could try to suppress a sigh for the total collapse and degradation of the English language and just give the writer the benefit of the doubt: it is presumably part of his or her idiolect.

Flaunt has been used to mean “flout” since the 1920s, according to the draft addition to the OED entry, and appears regularly, particularly in journalistic writing. At least one dictionary recognizes it as having that meaning; in the long run, others may accept it too.

On the other hand, if you are writing or editing something, there is an argument that it would be wise to maintain the distinction. In that way, you will avoid the involuntary sighs of many of your readers as they are distracted from the content of your message by what they see as a flaw in its form.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Grammar, Meaning of words, OED, Oxford Online Dictionary, Writing Skills Tagged: 20 confusable words

Flaunting the law or flouting the law? 20 words you shouldn’t confuse (5-6)

Put simply, it is this: Are people who write sentences such as “motorists who blatantly flaunt the regulations for their safety and well-being” (instead of flout) woefully ignorant dunderheads who need remedial English and should not be allowed into print, or are they just following a long-standing and perfectly legitimate linguistic trend?

How you answer that question defines your place on the descriptive-prescriptive spectrum (if you answer “yes”, you are probably an out-and-out prescriptivist). Your answer may also depend on where you live, and which dictionary or usage guide you take as your bible.

what do these words mean?

Though sounding similar, they have—at least in origin—very different meanings. If you flaunt something, you show it off in a way which is brash and overdone. The very use of the word suggests that  you don’t approve of whoever is doing the flaunting. Typical things that people flaunt are their wealth, their sexuality, and themselves.

you don’t approve of whoever is doing the flaunting. Typical things that people flaunt are their wealth, their sexuality, and themselves.

He flaunts his riches like everyone in the business.

Women should have it both ways—they should be able to flaunt their sexuality and be taken seriously.

Katie seemed to be flaunting herself a little too much for Elizabeth’s liking.

If you flout a law, rule, regulation, convention, and semantically related nouns, you do not obey them, and treat them with blatant disregard.

Around 10 smokers were openly flouting the ban when the Health Board’s environmental health inspectors arrived.

A quote from Chinua Achebe (1987) illustrates the confusion between the two. “Your Excellency, let us not flaunt the wishes of the people.” “Flout, you mean,” I said. “The people?” asked His Excellency, ignoring my piece of pedantry.

WHAT DO DICTIONARIES AND USAGE GUIDES SAY?

Merriam-Webster gives that transitive use of flaunt two definitions.

1 to display ostentatiously or impudently:

2 to treat contemptuously

while adding a note, which states that the use of flaunt in this way “undoubtedly arose from confusion with flout”, but that the contexts in which it appears cannot be considered “substandard”. Yet it hedges its bets by stating that “many people will consider it a mistake”.

On the other side of the pond, Oxford Dictionaries Online (ODO) states categorically that the two words “may sound similar but they have different meanings”.  The 1993 draft addition to the OED entry notes that the usage “clearly arose by confusion, and is widely considered erroneous”.

The 1993 draft addition to the OED entry notes that the usage “clearly arose by confusion, and is widely considered erroneous”.

Various British usage guides maintain the distinction rigidly, and the Economist style guide’s witty note runs “Flaunt means display; flout means disdain. If you flout this distinction, you will flaunt your ignorance”. The Australian Macquarie dictionary notes “Flaunt is commonly confused with flout”.

Nevertheless, ODO admits that in the Oxford English Corpus (OEC) “the second and third commonest objects of flaunt, after wealth, are law and rules”.

While that is true, closer inspection reveals that the “correct” flout the law, flout the rules, are several times more frequent, and this is borne out by the Corpus of Contemporary American. So, while Merriam-Webster is less prescriptive than Oxford, Macquarie, and British style guides, in that it accepts the “wrong” use, these figures suggest that many more people actually maintain the distinction than ignore it.

Furthermore, only a very small percentage of examples of flaunt in the OEC show it being used to mean “flout”.

Conclusion

Given the current state of things, any reply to my original question has to be nuanced. So, if you read something that contains collocations such as flaunt…rules, regulations, convention, you could try to suppress a sigh for the total collapse and degradation of the English language and just give the writer the benefit of the doubt: it is presumably part of his or her idiolect.

Flaunt has been used to mean “flout” since the 1920s, according to the draft addition to the OED entry, and appears regularly, particularly in journalistic writing. At least one dictionary recognizes it as having that meaning; in the long run, others may accept it too.

On the other hand, if you are writing or editing something, there is an argument that it would be wise to maintain the distinction. In that way, you will avoid the involuntary sighs of many of your readers as they are distracted from the content of your message by what they see as a flaw in its form.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Grammar, Meaning of words, OED, Oxford Online Dictionary, Writing Skills Tagged: 20 confusable words

October 15, 2014

To home in on or hone in on? 20 words not to confuse (3-4)

Which of these two sentences is correct?

A teaching style which homes in on what is important for each pupil.

Or

A teaching style which hones in on what is important for each pupil.

Where you live in the English-speaking world will affect your opinion.

Which also means that whichever version you use, someone somewhere will think it wrong.

Many people use hone in.

A US copywriter spotted “home in” in a blog of mine, and kindly pointed out what she thought was a typo. She was surprised when I told her it was intentional. In a straw poll in her office – this was in the US, remember – everyone agreed hone was correct.

Wearing my language purist hat, I would classify hone in as a malapropism or an eggcorn.  But wearing my descriptivist hat, I would have to say it is an example of language change in action.

But wearing my descriptivist hat, I would have to say it is an example of language change in action.

Home in is a metaphor, from home used as a verb to describe how a missile or aircraft is directed to a target, as in:

The other helicopter located the dinghy by homing in on the bleeping of the emergency distress call.

To hone means “to sharpen a knife with a whetstone”, or “to improve a skill or talent”.

What data is there?

I looked in the Oxford English Corpus, which consists of about 2.6 billion words of data from US, British and several other varieties of English.

First, home in is about 70% more frequent than hone in. But there is a noticeable contrast between British and US English. In US English, home in occurs 532 times, while hone in occurs 421 times. So, hone in constitutes getting on for half the total pie.

But in Britain the picture is rather different. Of the total pie, 85% are examples with home in.

What do dictionaries and usage guides say?

Oxford Dictionaries Online in both World English and US versions notes at home in on that hone is quite common in mainstream US writing, but that many people still consider it a mistake, as do Collins and freedictionary.com. Macmillan lists it with no comment.

The OED doesn’t classify it as a mistake. Instead it notes that it is “originally US”, and gives the earliest example from 1965. The revised (4th) edition of Fowler’s Modern English Usage covers similar territory to this blog.

On the other side of the pond, Merriam-Webster notes the existence of hone in and suggests that it “seems to have become established in American usage”. The American Heritage College Dictionary (2004) gives “to direct one’s attention; focus” as a meaning of hone in. Garner’s Dictionary of Legal Usage considers it unequivocally wrong.

So…?

The hone in variant has been around for nearly half a century. It is used in many parts of the Anglosphere. Some dictionaries list it without comment, while others warn against it.

If you use it, you will not be misunderstood. However, if you do use it, bear in mind that some people will consider it a mistake, and therefore conclude that you can’t use English “correctly”. And others will come to the same conclusion if you use home in.

To steer clear of the problem, why not use focus on, concentrate on, zero in on, or any other synonym that suits your context?

Filed under: Advice for writers, eggcorns, Grammar, Meaning of words, OED, Writing Skills Tagged: 20 confusable words, American Writing

To home in on or hone in on? 20 words you shouldn’t confuse (3-4)

Which of these two sentences is correct?

A teaching style which homes in on what is important for each pupil.

Or

A teaching style which hones in on what is important for each pupil.

Where you live in the English-speaking world will affect your opinion.

Which also means that whichever version you use, someone somewhere will think it wrong.

Many people use hone in.

A US copywriter spotted “home in” in a blog of mine, and kindly pointed out what she thought was a typo. She was surprised when I told her it was intentional. In a straw poll in her office – this was in the US, remember – everyone agreed hone was correct.

Wearing my language purist hat, I would classify hone in as a malapropism or an eggcorn.  But wearing my descriptivist hat, I would have to say it is an example of language change in action.

But wearing my descriptivist hat, I would have to say it is an example of language change in action.

Home in is a metaphor, from home used as a verb to describe how a missile or aircraft is directed to a target, as in:

The other helicopter located the dinghy by homing in on the bleeping of the emergency distress call.

To hone means “to sharpen a knife with a whetstone”, or “to improve a skill or talent”.

What data is there?

I looked in the Oxford English Corpus, which consists of about 2.6 billion words of data from US, British and several other varieties of English.

First, home in is about 70% more frequent than hone in. But there is a noticeable contrast between British and US English. In US English, home in occurs 532 times, while hone in occurs 421 times. So, hone in constitutes getting on for half the total pie.

But in Britain the picture is rather different. Of the total pie, 85% are examples with home in.

What do dictionaries and usage guides say?

Oxford Dictionaries Online in both World English and US versions notes at home in on that hone is quite common in mainstream US writing, but that many people still consider it a mistake, as do Collins and freedictionary.com. Macmillan lists it with no comment.

The OED doesn’t classify it as a mistake. Instead it notes that it is “originally US”, and gives the earliest example from 1965. The revised (4th) edition of Fowler’s Modern English Usage covers similar territory to this blog.

On the other side of the pond, Merriam-Webster notes the existence of hone in and suggests that it “seems to have become established in American usage”. The American Heritage College Dictionary (2004) gives “to direct one’s attention; focus” as a meaning of hone in. Garner’s Dictionary of Legal Usage considers it unequivocally wrong.

So…?

The hone in variant has been around for nearly half a century. It is used in many parts of the Anglosphere. Some dictionaries list it without comment, while others warn against it.

If you use it, you will not be misunderstood. However, if you do use it, bear in mind that some people will consider it a mistake, and therefore conclude that you can’t use English “correctly”. And others will come to the same conclusion if you use home in.

To steer clear of the problem, why not use focus on, concentrate on, zero in on, or any other synonym that suits your context?

Filed under: Advice for writers, eggcorns, Grammar, Meaning of words, Writing Skills Tagged: 20 confusable words, American Writing

October 13, 2014

Coruscating criticism or excoriating criticism?: 20 words not to confuse (1-2).

There are dozens of words that are all too easy to confuse. There’s [sic] the obvious case of its’s/its, not to mention there/they’re/their.

But then there are a host of others which are rather more uncommon, even literary. Since many are words generally found in formal or literary writing, readers of which are likely to be more literate themselves, and therefore more critical, it could be a bit embarrassing for you as a writer to mistake one for the other.

Here are two of my top twenty. It’s well worth paying particular attention to them.

coruscating/excoriating

Coruscating is a journalistic favourite. Hacks in particular light on it in order to embellish their prose, all too often with scant regard for its true meaning.

It derives from the Latin coruscāre “to vibrate, glitter, sparkle, gleam”; “glittering” or “sparkling”, literally or metaphorically, is what it means in English, e.g. She preserves the steely delicacy and coruscating wit of Wilde’s writing.

So, it puzzles me that, despite its relative rarity, it is commonly misused in phrases such as coruscating attack, criticism, review by mistake for the slightly less rare but equally Latinate word excoriating.

This is the participial adjective of the verb excoriate, which in English has been used to mean literally “strip the skin off” someone,  and non-literally “criticize them mercilessly”, e.g. Audiences are excoriated for not understanding what composers write.

and non-literally “criticize them mercilessly”, e.g. Audiences are excoriated for not understanding what composers write.

Even more embarrassing than misusing the word in the first place is to compound the stylistic felony by doubling coruscating’s single letter r, as noted in The Guardian’s Corrections and clarifications column: “In the following article, Terry Eagleton’s ‘corruscating [sic] review’ of Richard Dawkins’s book The God Delusion may have been withering or possibly even acidulous.”

Alternatives whose meaning would be clearer to reader and writer alike are blistering, devastating, and scathing.

cache, cachet

People sometimes use cachet when cache is required. Despite having five letters in common, and coming ultimately from the same French verb (cacher), in English they are completely unrelated. A cache of something is a “collection of items of the same type stored in a hidden place” such as an arms cache or a cache of gold and rhymes with cash.

Cachet is “prestige, high status; the quality of being respected or admired” and rhymes with sachet. The next two examples show the words being used correctly:

Several inmates seized a cache of grenades and other weapons and killed six security officers, including a high-ranking counterterrorism official;

The department stores knew they had to offer something different, something perceived to have more cachet.

In the next one, cachet is wrong, and cache would be correct: Egyptian excavators this week chanced upon a cachet of limestone reliefs.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Grammar, Meaning of words, Writing Skills Tagged: 20 confusable words

Coruscating criticism or excoriating criticism?: 20 words you shouldn’t confuse (1-2).

There are dozens of words that are all too easy to confuse. There’s [sic] the obvious case of its’s/its, not to mention there/they’re/their.

But then there are a host of others which are rather more uncommon, even literary. Since many are words generally found in formal or literary writing, readers of which are likely to be more literate themselves, and therefore more critical, it could be a bit embarrassing for you as a writer to mistake one for the other.

Here are two of my top twenty. It’s well worth paying particular attention to them.

coruscating/excoriating

Coruscating is a journalistic favourite. Hacks in particular light on it in order to embellish their prose, all too often with scant regard for its true meaning.

It derives from the Latin coruscāre “to vibrate, glitter, sparkle, gleam”; “glittering” or “sparkling”, literally or metaphorically, is what it means in English, e.g. She preserves the steely delicacy and coruscating wit of Wilde’s writing.

So, it puzzles me that, despite its relative rarity, it is commonly misused in phrases such as coruscating attack, criticism, review by mistake for the slightly less rare but equally Latinate word excoriating.

This is the participial adjective of the verb excoriate, which in English has been used to mean literally “strip the skin off” someone,  and non-literally “criticize them mercilessly”, e.g. Audiences are excoriated for not understanding what composers write.

and non-literally “criticize them mercilessly”, e.g. Audiences are excoriated for not understanding what composers write.

Even more embarrassing than misusing the word in the first place is to compound the stylistic felony by doubling coruscating’s single letter r, as noted in The Guardian’s Corrections and clarifications column: “In the following article, Terry Eagleton’s ‘corruscating [sic] review’ of Richard Dawkins’s book The God Delusion may have been withering or possibly even acidulous.”

Alternatives whose meaning would be clearer to reader and writer alike are blistering, devastating, and scathing.

cache, cachet

People sometimes use cachet when cache is required. Despite having five letters in common, and coming ultimately from the same French verb (cacher), in English they are completely unrelated. A cache of something is a “collection of items of the same type stored in a hidden place” such as an arms cache or a cache of gold and rhymes with cash.

Cachet is “prestige, high status; the quality of being respected or admired” and rhymes with sachet. The next two examples show the words being used correctly:

Several inmates seized a cache of grenades and other weapons and killed six security officers, including a high-ranking counterterrorism official;

The department stores knew they had to offer something different, something perceived to have more cachet.

In the next one, cachet is wrong, and cache would be correct: Egyptian excavators this week chanced upon a cachet of limestone reliefs.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, Grammar, Meaning of words, Writing Skills Tagged: 20 confusable words