Jeremy Butterfield's Blog

May 28, 2025

The cultural significance of ladybirds across languages

I’m not sure when I first knew about ladybirds – perhaps as a child of five or six. At that age you’re closer to the ground and so much closer to small creeping things than you’ll ever be again, able to observe them with that goggle-eyed curiosity born of novelty. The age when a lifelong passion for insects first fires up to forge you as an entomologist.

Or not, in my case.

I’m more of the etymologist persuasion, that inclination so often confused with the insecty one. Last spring, however, I was fascinated to see dozens of ladybirds on the stems and flowerheads of our Euphorbia amygdaloides var. robbiae, also known as Mrs Robb’s bonnet. That fount of all knowing, the interweb, tells me such a site for overwintering is not unusual. Ladybirds perform the useful task of snaffling aphids on an industrial scale.

Image courtesy Martti Salmi on Unsplash

Image courtesy Martti Salmi on UnsplashEvery day I get a Danish word of the day to help with my learning. One such was mariehøne, ‘ladybird’, literally ‘Mary hen’.

Which led me to ask where the ‘Mary’ part came from.

Your house is on fireUnlike me until recently, you probably already knew that the Mary in question is Our Lady of Sorrows, the Virgin Mary. The native British ladybird typically, but not always, has seven spots. Seven is the number of Mary’s sorrows, which start with Simeon in the Temple at the time of Jesus’ presentation:

‘And Simeon blessed them, and said unto Mary his mother, Behold, this child is set for the fall and rising again of many in Israel’

meaning that some will rise in faith and be blessed and others fall away. Then Simeon tells Mary: ‘Yea, a sword shall pierce through thy own soul also.’ Mary, ‘Our Lady of Sorrows’ or ‘Mother of Sorrows’, Mater Dolorosa, is portrayed in the goriest versions of Catholic art pierced by seven rapiers, as in this gloriously gruesome image from the Chapel of the True Cross (CapilIa de la Vera Cruz) in Salamanca, Spain.

Aged five or six I had no idea about all that bloodthirstiness. But what I do remember is, in company with other playmates, picking ladybirds delicately up and then softly blowing them off my hand to the incantation of ‘Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home, | Your house is on fire and your children are burnt.’ Nobody knows for sure how old it is, but it’s recorded in the earliest known book of nursery rhymes, Tom Thumb’s Pretty Song-Book of 1744, which measures a diminutive 3 x 13⁄4 inches, to fit snugly into a child’s paw.

And your children are burntOther languages load this inoffensive and beneficial insect with religiosity. In German it’s ein Marienkäfer (Mary’s beetle) and in Swedish Jungfru Maria(s) nyckelpiga (Virgin Mary’s keyholder, literally ‘key maid’). In Irish it’s bóín Dé, which I believe means ‘God’s little cow’, an association that appears in Russian too, with бoжья коровка and in Argentina with vaca de San Antón (St Antony’s cow). Presumably the spots are reminiscent of a cow’s hide.

May 21, 2025

What’s the opposite of a placebo?

Last week I posted about the mock-Latin origins of gazebo and, tangentially, about Jane Austen and ha-has.

My point about gazebo is that it imitates Latin, specifically, the second conjugation first-person future indicative. Two other words with the same grammar immediately come to mind: placebo and nocebo. One is familiar in its modern psychological sense but goes back to mediaeval Latin; the other is a relatively modern invention, far less often used than its positive twin.

You’ll probably have come across placebo in one of its two modern meanings; a) ‘a medicine or procedure prescribed for the psychological benefit to the patient rather than for any physiological effect’; or b) ‘a substance that has no therapeutic effect, used as a control in testing new drugs’ (definitions taken from the Online Oxford Dictionary).

The first meaning goes back to 1770 and is defined with admirable and elegant concision in this 1811 quotation from a medical dictionary:

Placebo,… an epithet given to any medicine adapted more to please than benefit the patient.

R. Hooper, Quincy’s Lexicon-medicum (new edition)

A 1938 quotation, from a journal of the American College of Physicians, sceptically and wittily explodes much of the history of medicine:

The second sort of placebo, the type which the doctor fancies to be an effective medicament but which later investigation proves to have been all along inert, is the banner under which a large part of the past history of medicine may be enrolled.

Annals of Internal Medicine vol. 11 1417

The earliest OED citation for the second meaning, i.e. as a control, is from 1950, but I’ve no idea if that is truly the earliest evidence for that use (trigger warning for those who prefer data as an uncount noun):

It is… customary to control drug experiments on various clinical syndromes with placebos especially when the data to be evaluated are chiefly subjective.

Journal of Clinical Investigation vol. 29 108/2

The scientific literature is full of examples of experiments where people have derived real physiological benefits from medicines or drugs which in principle exerted no actual effect on their bodies. In other words, any benefit may originally have been ‘all in the mind’, but it translated to the body.

If a placebo is a medicine given to a patient for its beneficial psychological effect, what, then, is a nocebo, literally ‘I shall harm’?

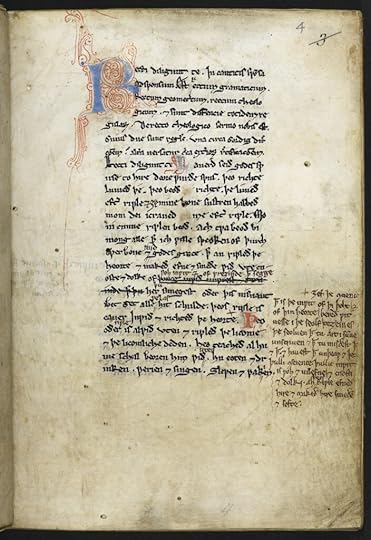

A page from the earliest copy of the Ancrene Riwle, held by the British Library, Cotton MS Cleopatra C VI, f. 4r.

A page from the earliest copy of the Ancrene Riwle, held by the British Library, Cotton MS Cleopatra C VI, f. 4r. Again, according to Oxford, it’s ‘a detrimental effect on health produced by psychological or psychosomatic factors such as negative expectations of treatment or prognosis.’

It’s first recorded from 1961.

That’s a harder idea to get your head around. A couple of the OED examples seem helpful. The OED also points out that it’s mainly used in the phrases nocebo effect and nocebo response and that it often applies to negative effects experienced after the administration of a placebo.

Attempts to define the secondary effects of placebos, i.e., the nocebo effect.

Encephale vol. 58 486 1969

Patients experiencing the nocebo effect… presume the worst, health-wise, and that’s just what they get.

Washington Post 30 April (Home edition) f1/2 2002.

I’ve looked for examples, and AI was helpful. For instance, patients might experience nausea or drowsiness when taking medication if they’ve been told they will, even if what they’re taking has no physiological effect because it’s a placebo. In other words, placebos and nocebos both illustrate how our expectations and beliefs can affect our experience in direct ways.

(Note, incidentally, the plurals in –os rather than –oes.)

Such thoughts were far from the mind of the person who first recorded placebo back in the early thirteenth century, in the Ancrene Riwle, the rules governing the life of anchorite nuns.

Like lavabo, discussed in last week’s post, the word’s origins are religious. It repeats the first word of the first antiphon of the Vespers for the Dead ‘Placebo Domino in regione vivorum’ (Psalm 114, Vulgate), ‘I will please the Lord in the land of the living.’

The other second conjugation verb in English we probably all know is habeas corpus. But that’s for another time.

May 14, 2025

Gazebos and Jane Austen – or not

As I write, my partner and I are on holiday in our favourite hideaway, buried in the heart of the Herefordshire countryside. Where we stay is a converted railway station on an extinct country line from Ross-on-Wye that was zapped by the Beeching Report in the 1960s. In its extensive gardens sits a gazebo where, weather permitting, we spend a lot of time chatting, browning our protruding legs and reading.

Image of a glorious gazebo courtesy of Brice Curry on Unsplash.

Image of a glorious gazebo courtesy of Brice Curry on Unsplash. A book I’ve been rereading here is Sense & Sensibility. Gazebo to me sounds very Jane Austen, just as a ha-ha does. But, disappointingly, a website that’s a thesaurus of every word she ever used assures me gazebos do not figure in her writings (but I’m happy to be corrected if someone tells me they do, and where). Nevertheless, I maintain it’s the sort of word that ought to have occurred, redolent as it is of some of the country estates — Mansfield Park, Barton Park, etc. – she set her comedies of manners in. Otherwise, you might think I was merely clickbaiting you.

And speaking of Mansfield Park, thanks to one of my readers, I am reminded that Austen situates a ha-ha at the grand mansion that is Sotherton, home of Maria Bertram’s betrothed, James Rushworth. On a walk in the grounds, Maria and Henry Crawford are determined to reach a knoll in the ‘park’, but the gate to the park is locked. Maria, egged on by Henry, decides she can slip round it, which horrifies her strait-laced cousin Fanny:

“You will hurt yourself, Miss Bertram,” she cried; “you will certainly hurt yourself against those spikes; you will tear your gown; you will be in danger of slipping into the ha-ha. You had better not go.”

The blindingly obvious phallic imagery of the spike tearing a gown, and symbolically, Maria’s virginity, foreshadows the disgrace caused by her later elopement with Henry Crawford.

Which language?Which language do you think gazebo comes from? Perhaps Italian, because of it’s –o ending, like piano or casino or ghetto? Or maybe Spanish? Or even Arabic, a gazebo being a bit like a tent travellers across the sands might pitch?

If it’s possible to describe words as ‘made up’, this one certainly fits that bill. It’s probably an invention based jestingly on Latin: it jokingly conjugates to gaze as if it were a Latin verb gazēre, ‘I shall gaze’, in the first-person singular future indicative.

No doubt, whoever first coined it and the people who first heard it thought it a terrifically clever learned wheeze. The OED first cites it from 1741, well before Jane Austen’s birth (1775), in a work by the Irishman Wetenhall Wilkes titled An Essay on the Pleasures & Advantages of Female Literature:

Unto the painful summit of this height | A gay Gazebo does our Steps invite. | From this, when favour’d with a Cloudless Day, | We fourteen Counties all around survey.

Mr Wilkes was clearly a bit of a mansplainer avant la lettre. Another work of his was A letter of genteel and moral advice to a young lady: being a system of rules and informations, digested into a new and familiar method, to qualify the fair sex to be useful, and happy in every scene of life.

His poetic lines display one meaning of gazebo, ‘A turret or lantern on the roof of a house, usually for the purpose of commanding an extensive prospect’ as the OED puts it. But nowadays the word means a roofed or tented structure in a garden, with open sides to provide shelter from the elements while allowing a view from within. These can be pop-up affairs with a canvas or similar roof, to provide shelter on beaches or in gardens, or sturdy, solid constructions, like ours, with its wooden posts, beams and roof.

If mock-Latin is indeed its origin, gazebo is not the only first-person singular future indicative Latin verb lurking in English. If you visit ruined monasteries, as we often do, the guidebook may draw your attention to a lavabo for the monks, a trough or basin for them to wash their hands in, sometimes built into a wall and furnished with a water supply and a drain. Wenlock Abbey has a notable free-standing one.

Lavabo, the physical object, comes from the earlier lavabo, the ritual washing of hands by the priest during celebration of the Eucharist, at which he recited Lavabo inter innocentes manus meas, ‘I shall wash my hands among the innocent’ (Psalm 26:6ff.). Since Vatican II, this has been replaced by Lava me, Domine, ab iniquitate mea, et a peccato meo munda me (‘Lord, wash away my iniquity; cleanse me from my sin’).

Lavabo is from a first conjugation Latin verb. Two more futures from the second conjugation are placebo and nocebo. I’ll come back to them in the next post.

April 30, 2025

Another cod etymology bites the dust.

February 17, 2025

An expert talks about ‘Words of the Year’ – what they are and what they’re not.

January 25, 2025

Burns Night and Burns Suppers

This 25 January, as every year, people in Scotland, Britain and the worldwide Scottish diaspora will gather merrily to celebrate the birth date of Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns. Though it’s a gathering now as jolly as any birthday party, the event started life as a commemoration of Burns’ death in 1796 at the young age of thirty-seven. In 1801, a group of nine of his friends met at the Burns Cottage in Alloway, Ayrshire, on what would have been his birthday to reminisce about him and then turned their gathering into an annual event. Now it’s celebrated by countless millions. Other poets, like Keats, Shelley and Chatterton died untimely, but none has ever lodged so firmly in so many people’s hearts.

Over the decades and centuries since that first gathering an order of service, as it were, has sprung up for Burns Night or a Burns Supper. But a Google search suggests plenty of uncanonical interpretations, such as a Burns Supper on a double-decker bus, an underwater Burns Supper (how?) or on the former Royal Yacht Britannia. Some venues even seek to cash in on the occasion by turning it into a fully-fledged Burns Day.

Apologies to those who know the drill like the back of their hands. What follows is for those unfortunates who won’t be attending a Burns Supper, or for novitiates.

And some wad eat that want it;Exact arrangements vary, but the running order of a typical Burns supper goes like this:

The host – or staff member acting as such at a commercial venue – says a few words about why everyone’s gathered, and when people are seated, recites the Selkirk Grace.

Its four lines, shown in the headings of this post, celebrate our good fortune in having enough to eat and thank the Lord. They’re in Scots and display typical features: verb forms differing from Standard English, like hae (‘have’), wad (‘would’), thankit (‘thanked’), and different spellings reflecting pronunciation, like sae for ‘so’.

It’s popularly believed that Burns wrote this grace. He didn’t. It existed in the seventeenth century as ‘The Covenanters’ Grace’. Burns recited it at supper at the Earl of Selkirk’s – there’s still an earl of that title – in 1794, and at other times, so it became indelibly associated with Burns’ name.

If there’s to be a starter a soup as hearty and nourishing as Cullen skink or cock-a-leekie would be appropriate. Some eateries will serve the haggis as a starter or even a ‘gateau’ and then have a meat main dish, which might include skirlie (yuy-yum) as an accompaniment.

But the highlight is of course the presentation of the haggis, traditionally piped in on a silver salver. At home, you might serve it more simply on an ashet.

Both words are interesting. Salver took the French salve and added an –r to give an –er ending on the analogy perhaps of platter; ashet is a reformulation in British mouths of French assiette, ‘plate’ and is a mainly Scots word.

The host or other officiant then recites Burns’ famous ‘Address to a Haggis’. Only after that can people tuck in to their haggis, which should always be served with neeps (short for turnips) and tatties (Scots for potatoes). And often with a whisky and cream sauce.

On the perennially vexed question of ‘when is a turnip not a turnip’, what Scots mean is often Brassica napus, which others would call a ‘swede’ or ‘rutabaga’, as opposed to the smaller and generally white-fleshed Brassica rapa turnip. Funnily enough, though neeps might be Scots, and dialectal elsewhere, it comes from Old English næp, which is a direct borrowing from the Latin nāpus you can see above in the botanical name.

But we hae meat, and we can eatRemembering the whole ‘Address to a Haggis’ is a major memory feat, especially because several words may be unfamiliar to the reciter outside the world of the poem. Possibly, the simple rhyme pattern AAABAB helps, as it gaily drives the narrative forward over the work’s eight stanzas and forty-eight lines.

For those pressed for time, here’s my free summary. Please spare the brickbats.

What a glorious-looking and -smelling thing is a haggis, the pinnacle of pudding perfection! As men race to tuck in, one man who’s fit to burst says grace. Forget your fancy foreign grub: it would give a sow the boke and so enfeeble men they’re like a withered rush. The haggis-fed rustic with sword in hand will hack off heads and limbs like thistle tops. Give Old Scotland haggis, not poncey soups!

For anyone wanting the organ grinder, not the monkey, the link to the unadorned full text is here.

If you know none of the rest of the poem, many readers will, I’m sure, be familiar with the opening couplet.

Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face,

Great Chieftain o’ the Puddin-race!

It’s worth stating, because we’ve probably forgotten through familiarity, that addressing a haggis is a startlingly novel and hilarious example of personification, designed to bring a smile to the listeners’ faces from the start. And if you’re wondering how a haggis can be a ‘pudding’,* it very much is one according to the fourth Collins definition: ‘a sausage-like mass of seasoned minced meat, oatmeal, etc, stuffed into a prepared skin or bag and boiled’. In haggis, the ‘minced meat’ is lamb.

Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face,

Great Chieftain o’ the Puddin-race!

‘Fair fa’ in that first line is a formulaic ‘expression of blessing’, using the Scots variant fa of fall. Sonsie is a highly polysemous word, to use the lexicographical jargon: it has many meanings. As part of personification, the line reapplies the meaning ‘comely’ or ‘bonny’ from people to a thing, as you can see in 3 (3) of the Dictionaries of the Scots Language online. In that same entry, there’s a nice quote for another meaning of sonsie, ‘engaging and friendly in appearance or manner’: ‘Burns was handsome and sonsie, courteous and brave, clever and self-perceptive.’

I’d love to go on with my commentary, but there’s not room. And you may be relieved. If you wish to explore further, this link has a parallel translation in Standard English. And this one glosses the unfamiliar words. There, that should cover all bases.

Poor devil! see him owre his trash,

As feckless as a wither’d rash.

The only other linguistic comment I’ll make is that feckless in stanza 6 means ‘weak, feeble’, not its often-used meaning of ‘irresponsible’.

And sae the Lord be thankit.Back at ‘the order of service’, after the haggis or main course, there could be pudding or dessert. (I noticed several venues offering cranachan, yum-yum, a Scottish Gaelic word.)

There could be another Burns reading.

Next comes the section when the host or speaker comments on Burns’ importance and legacy in the ‘Immortal Memory’.

Then there could be a further Burns reading, followed by a ‘Toast to the Lassies’, who may then reply with ‘A Reply to the Toast to the Lassies’, sometimes called ‘Toast to the Laddies’.

Finally, there could well be some Scottish dancing to a band in a ceilidh, another Scottish Gaelic word (pronounced KAY-lee). And then a rousing rendition of ‘Auld Lang Syne’.

I’ve left a couple of words uncommented. So, to finish, whisky is from Gaelic, shortened from whiskybae, from Scottish Gaelic uisge beatha, literally, ‘water of life’. And if you take a ‘wee dram’ of whisky, you’ll be using a word, dram, that goes back to the Classical Greek drachma, the coin. How so? Because fifteenth-century apothecaries brought it into English from French, which in turn took it from Late Latin, as a unit of measurement supposedly equivalent to the weight of the coin, or one-eighth of an apothecary’s ounce.

Cullen in the Cullen skink starter mentioned is a wee village on the North-East coast of Scotland. The skink is from a Middle Low German word meaning a ‘shank, shinbone’ and is directly cognate with Modern German Schinken and Danish skinke, ‘ham’. You see, before fish became part of the recipe, a shin of beef would be used to make a skink, a potage or soup.

That same noun skink produced the verb in the final stanza of ‘Address to a Haggis’, meaning the thin, clear, watery soups that Burns objected so strenuously to.

Auld Scotland wants nae skinking ware,

That

jaups

in luggies.

(‘splashes in small wooden dishes’)

My partner and I will be celebrating in York.

Meanwhile, wherever you are, here’s a toast to you on Burns Night: slàinte mhath! (slan-jee-var).

* I expatiate on puddings in this November post for British Pudding Day.

This is a version of a post originally published on the Collins Dictionary site here.

Image: courtesy of Nina Garman on Pixabay.

January 20, 2025

Penguin Awareness Day, penguin suits, Penguin books & Welsh

Image by Siggy Nowak from Pixabay5-minute readPenguins

Image by Siggy Nowak from Pixabay5-minute readPenguinsIt’s #penguinawarenessday today. Which is a jolly good thing since, I suspect, most people other than Pingu fans and naturalists will be blissfully unaware of them for the rest of the year.

I bet you’ll never guess from which language English borrowed penguin. Could it be from those adventurous mariners the Dutch, as their word is pinguïn? Or perhaps from a Polynesian language? Nope, neither of those. It’s most probably from…

…

…

…

…

Welsh.

Which is interesting, because very few Welsh words have entered the mainstream of English, the royal corgi being a highly visible exception.

The Welsh origin is from pen meaning ‘head, headland’ and gwyn meaning ‘white’. And according to the OED etymologists it was probably first applied to the now extinct Great Auk. The pen part features in Penzance, Penmaenmawr and Penrith, and gwyn in the Christian names Gwyn, Gwynn, Gwynne.

Infinite were the Numbers of the foule, wch the Welsh men name Pengwin & Maglanus tearmed them Geese.

That’s an extract, dated 24 August 1577, from the log kept on the Golden Hinde by the priest Francis Fletcher on Sir Francis Drake’s circumnavigation of the world. (‘Maglanus’ we know as Magellan.)

Having waddled into English, the word has dived into other languages such as French pingouin or Russian пингвин (peengveen) or Finnish pingviini. In French, some people use pingouin to mean ‘penguins’, but this is frowned upon by naturalists, since technically it refers to auks. Manchot is the preferred term.

The list at the foot of the Collins entry for penguin shows how most European languages have adopted the word, including Greek πιγκουίνος, but the odd-person-out is Czech with its tučňák. I am reliably informed that’s because it’s a sort of compound consisting of the adjective tučný, ‘fatty’ and the affix –ák, which suggests the referent has the characteristic just named.

We so often use words and phrases that characterise human behaviour in animal terms. Some obvious examples: a nasty man is a swine; a wily one is an old fox; a greedy person is a pig or a gannet, and a treacherous friend is a snake. (Add your own examples here ****************)

Those words above used metaphorically draw on a central conceptual metaphor: PEOPLE ARE ANIMALS.

What’s more, when we liken someone’s behaviour to that of an animal, the behaviour concerned is almost always bad, as the previous examples suggest (The early bird catches the worm is a fairly rare exception).

What we’re doing with that kind of language is making use of the overarching conceptual metaphor BAD HUMAN BEHAVIOUR IS BAD ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR.

Sweeeeeeeet!If you watch footage of penguins moving on land, they look clumsy, comical, almost touchingly vulnerable, quite endearing in their ridiculousness, even sweeeeet. But the metaphor we draw from their behaviour is the opposite of warm or affectionate. As the OED puts it: ‘humorous or derogatory. A man wearing black-and-white evening dress, esp. one having a stiff or pompous demeanour’.

The earliest use comes from that now-defunct engine of lively prose and teenage excitement, Melody Maker, 1 April 1967:

Good Music had the sort of melody and clipping beat that even Victor Sylvester didn’t have to alter so that the Brylcreemed penguins and their sequined partners could jig about in the ballrooms.

Even better, because it suggests pomposity beyond the starchiness, is this from 1996:

When, for the third time, a penguin with attitude announced the absence of a number of menu dishes, I felt distinctly uneasy.

Eat Soup Dec. 45/2

Photo courtesy of Ian Parker on Unsplash.

Photo courtesy of Ian Parker on Unsplash.Away from the realms of imaginative writing, penguin suit for evening dress and white shirt is a phrase anyone might use. It dates back to the very beginning of the 1960s (I bought myself a penguin suit. M. Terry, Old Liberty 36, 1961), while this next quote neatly epitomises the convention-hating attitude of the decade:

Some smooth bastard in a penguin suit. R. Jeffries Traitor’s Crime iv. 46, 1968.

What was news to me, courtesy of the OED, is that penguin suit can also mean astronauts’ gear:

The astronauts donned the tight-fitting overalls, known as a penguin suit, in which tension is produced by several layers of rubberized material.

N.Y. Times, 10 June 1971

The most visible penguin in people of a certain age’s lives will have been the one on the covers of the hugely successful Penguin paperback series, launched in 1935 and still going strong. It was chosen as the symbol as something ‘dignified but flippant’.

Those paperbacks did not stand up to repeat handling. I remember dutifully covering mine with transparent adhesive plastic (now, memory, just what was it called?) to make them last longer and stop grubby fingerprints or Marmite stains sullying their sunshiny orange. You had to spread the plastic ever so, but ever so carefully to make sure no bubbles or blisters disfigured your book’s synthetic second skin.

Some choice quotations from famous authors referencing the Penguin paperbacks are at the end of this blog.

Meanwhile, English being so footloose – nay, cavalier – with parts of speech, it was inevitable that Penguin books should hatch a verb. Its parent seems to have been a rather snotty GBS in a 1941 letter:

I have had to let Pygmalion be penguined. My days of respectable publishing are over, I fear.

24 Feb. in Coll. Lett. 1926–50 (1988) 597

The phenomenon of Penguining is past its peak; nowadays much fiction and non-fiction appears first in hardback and then paperback, regardless of publisher. In this next quote, the author is looking back to that golden age. But there is a vast range of Penguin Classics.

For an author, to be ‘Penguined’ was a mark of high merit.

J. Sutherland, Bestsellers ii. 30, 2007.

Finally, the Chambers Slang Dictionary and Wiktionary concur that penguin is slang for a nun (black habit, with white wimple, coif, etc.). Wiktionary also claims it is a juggling manoeuvre: ‘A type of catch where the palm of the hand is facing towards the leg with the arm stretched downward, resembling the flipper of a penguin’.

And last of all, Urban Dictionary suggests it describes a way of keeping warm: ‘When two or more people try and stand as close together as possible with both hands in their pockets to avoid cold weather and strong winds’. That is a deeply attractive metaphor, but I have no idea whether people actually use it.

Penguin BooksThe TLS gives them its blessing, 1 August 1935:

We shall look forward to more Penguin Books, and we wish the experiment—a bold one—all success.

Orwell reads a stack of them to while away the time as he sits on a roof in Barcelona in the early days of the Spanish Civil War:

Sometimes I was merely bored with the whole affair, paid no attention to the hellish noise, and spent hours reading a succession of Penguin Library books which, luckily, I had bought a few days earlier; sometimes I was very conscious of the armed men watching me fifty yards away.

Homage to Catalonia x. 177, 1938 (1937)

Dame Iris in the person of one of her characters dismisses Penguin’s polight English fiction:

There were a few Penguin novels, but they looked dull English tea-party stuff.

I. Murdoch, Unofficial Rose v. 51, 1962

And someone writing in The Scotsman skewers the pretensions of a fresher:

A spotty first-year student in faculty scarf and tweed jacket, reading a Penguin Classic while trying to light a brand-new pipe.

Scotsman (Nexis) 11, Nov. 5 2002

“penguin, n.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, December 2020, oed.com/view/Entry/140106. Accessed 13 January 2021.

Chambers Slang Dictionary, Jonathon Green, 2008. Edinburgh: Chambers.

Collins English Dictionary online.

NB: This is an updated version of a post published on Penguin Awareness Day in 2021.

December 21, 2024

Festive tradtions — pre- and post-Christmas & Hanukkah

Ah! British Christmas. So cosy, so nostalgic. What’s not to love about this time of year? Christmas cards and carols and Christmas trees and cake and plum pudding and turkey and cranberry sauce and mulled wine and kissing under the mistletoe and Boxing Day walks. And if we’re lucky, snow. All so very trad, so very heart-warming, so very British.

Yet even seemingly unchangeable traditions once upon a time weren’t traditions at all. And some traditions die: it used to be the norm to put up your tree only on Christmas Eve, whereas nowadays most go up well before. Christmas markets didn’t exist in this country until a few years ago, but we’ve adopted this Continental habit with gusto.

To an extent, our modern Christmas is a Victorian invention. That’s true for the cards and the trees and the mulled wine and the turkey and the kissing under the mistletoe, which nobody knows how began. (The –toe part has nothing to do with feet, though confusing it with toes started as long ago as Old English. It’s a distorted version of the OE word tān, ‘twig’, so it’s a ‘mistle twig’.) If any of these traditions existed before, such as eating turkey, associated with Christmas even in the Tudor period, they were strengthened in Victorian times. And when we eat turkey, we’re eating a sort of misnomer: originally Turkey cock referred to a guinea fowl, and then when turkeys first arrived from across the Atlantic they were wrongly thought to be a species of that bird.

and the goose is getting fatWe share society with people of different religions and faiths or no religion at all. The shift to talking about or advertising ‘the Festive season’ rather than ‘Christmas’ arguably reflects this. One could even argue, persuasively or not, that the ‘season’ more accurately reflects what happens in the lead-up. ‘Christmas isn’t just for Christmas’, to coin a phrase.

One major ‘festive season’ celebration, on 6 December, concerns St Nicholas, the saint who ultimately morphed into Santa Klaus and is the patron saint of New York, Russia and Greece. Even today, in Belgium, and especially Flanders, Sinterklaas, dressed in scarlet bishop’s robes, sporting a luxuriant white beard and crowned with a mitre, gives presents to good children on 6 December. And in the Netherlands, apparently, about a third of the population give presents only on St Nicholas’ Day. Similar traditions obtain in the Italian-speaking cantons of Switzerland, in Northern Italy and Slovenia.

The ‘season’ sets off earlier each year in the UK. When the first Christmas jumper is donned is a personal choice, but I spotted my first one on 29 November – worn by a salesperson. Christmas Jumper Day itself falls on 13 December, a respectable twelve days before the main event.

Except, of course, that 25 December isn’t necessarily the ‘main event’ even for practising Christians. In Hispanic countries la Nochebuena (literally ‘the good night) and in France Le Réveillon de Noël are when the feasting takes place, on Christmas Eve. I remember being in Madrid one 25 December and going to the cinema that day, which provoked a mild sort of cognitive dissonance.

Please to put a pennyDecember is also an eventful month for Judaism. Hanukkah/Chanukah, which in Hebrew means ‘dedication’, covers eight nights and days celebrating the rededication of the Temple in Jerusalem after its recapture from the Greeks by the Maccabees in 164 BC. Central to the celebration is the ritual lighting of a hanukiah, a candelabrum with nine arms and cups, rather than the seven of the menorah. The reason the festival lasts eight days is that’s how long the small jar of oil found in the temple burned, rather than the one day it was expected to last. The central holder of the hanukiah contains the ‘helper’ candle, the shammash, used to light the others over the eight days.

If you’re wondering if Hanukkah and Chanukah are different, no, they’re not, they simply reflect different transliterations of the Hebrew first letter of the word, ḥeth (ח). That sound in Modern Hebrew (a voiceless uvular fricative [χ]) is broadly similar to the ch of loch pronounced by a Scot, and accordingly the sound was first transcribed as ch-. However, ch– at the beginning of a word is likely to be pronounced in a standard way, as in chair, so the h– replaced it – and is, additionally, slightly closer to the sound in Biblical Hebrew.

Hannukah places light at its centre, symbolic of spiritual illumination; indeed, it’s also known as the ‘Feast of Lights’. Light symbolism plays a hugely important role in Christian Advent, too, in recognition of the symbolic significance of light in the Bible and in particular of Jesus’ words in the Gospel of St John, ‘I am the light of the world…’, ‘Ego sum lux mundi…’ (8:12). On Advent Sunday, the evening service at York Minster starts in almost pitch darkness. In a powerfully symbolic ritual, one by one each member of the congregation lights the candle they hold so that they journey literally from darkness to light.

And in the murky depths of midwinter in Sweden, where December days are at their briefest, light and the person who symbolically delivers it assume a poetic resonance. In mid-December Swedes celebrate the Feast of Sankta Lucia, Saint Lucy, an early fourth-century Sicilian martyr, and this is a major part of their Advent tradition. Lucy’s very name derives from the Latin for ‘light’, lux. In Swedish churches on 13 December, a woman representing her leads a group of others, all robed in baptismal white and bearing candles, while she is crowned with a wreath of lighted candles.

in the old man’s hatThat thirteenth of December date was once hugely significant because it marked the winter solstice in the Julian calendar. It was kept for Sankta Lucia even though the calendar changed to the Gregorian.

And on this winter solstice, 21 December, pagans, druids and others will gather to celebrate at Stonehenge, in Wiltshire, England. Finally, thinking about faith-based events before Christmas, Bodhi Day on 8 December celebrates the date on which the Buddha achieved enlightenment – bodhi in Sanskrit, a language which has donated scores of loanwords to English and sits in the table of donor languages between Portuguese and Russian.

So much for what happens pre-Christmas. But why do we celebrate Jesus’ Nativity on 25 December anyway? After all, we have no dated birth certificate.

The date was first commemorated in 336 under the Emperor Constantine (who incidentally was proclaimed emperor at York in AD 306, quite possibly where the Minster now stands.) In Constantine’s time two pagan beliefs which have potent symbolic parallels with the Nativity were celebrated on that same date: first, Sol Invictus (‘unconquered sun’) the reborn sun god, marking the return of longer days after the winter solstice; second, Mithra, the god of light associated with the sun whose cult was hugely popular among the Roman legions.

Come 26 December we may already have celebrated the Nativity in the West, but some orthodox churches don’t until 7 January. Again, as with St Lucy, that’s the result of the difference between the Gregorian and Julian calendars; our Gregorian 7 January is the Julian 25 December and orthodox Churches in Russian, Serbia, Georgia and elsewhere follow the Julian calendar, which is thirteen days behind, for religious purposes. And meanwhile, Hanukkah will just have begun because this year its start coincides with Christmas Day. It’s always on the twenty-fifth day of the Jewish month of Kislev, but it’s literally a ‘moveable feast’, because that date changes each year when transferred to the Gregorian calendar.

And while many good little girls and boys will already have received their presents on 25 December, if they’re of Luso-Hispanic or Italian heritage, they might have to wait till 6 January, the Feast of the Epiphany, or la Befana in Italian (derived from the Italian Epifania) or ‘Day of the Kings’ in Portuguese and Spanish, Dia de Reis and Día de Reyes, respectively.

Whichever ‘winter feast of your choosing’* you tuck into, I hope it’s as scrumptious as you expect it to be.

Merry Christmas!

* A phrase coined recently by Tim Hayward of the BBC’s radio programme The Kitchen Cabinet.

This is a transcription of a post originally written for Collins Dictionaries. You can view it here.

Image: courtesy of Jamie Street on Unsplash.

December 18, 2024

By the same token

You could have knocked me down with the proverbial feather the other day when on BBC Radio 4 I heard the enjoyably ‘verbal’ Jay Rayner use a phrase I hadn’t heard in yonks:** ‘by the same token’.

The context was a discussion on that entertaining BBC cookery programme The Kitchen Cabinet raised by a certain James about whether truffles are overrated and what other ingredients the panel of experts thought were equally so.

Discussion veered off onto what foods you shouldn’t have to eat if you don’t want to, brussels sprouts being one, with the great retort, ‘How can I make brussels sprouts nice?’ – ‘By not eating them.’

That speaker finished with ‘If you don’t like brussels sprouts, just stay away’, and then Jay rounded off the discussion: ‘And by the same token, James, if you don’t really like truffles, you don’t have to eat them.’

By the same token. What on earth does it mean?

It made my antennae quiver because, in the dim and distant past, before language databases were invented, we harmless drudges had to invent ‘natural-sounding’ examples to put in dictionaries to illustrate how a word or phrase might be used.

More than that: applying for my first job as a lexicographer at Collins back in the eighteenth century, I was sent various tests – by post, believe it or not, or snail mail. One included providing definition and context for twenty idiomatic phrases, one of which was ‘by the same token’.

My definition was ‘for the same reasons and in the same way’, I’m very sure, because I can still remember it: I was pleased with its concision. But I’ve no idea how my made-up example went.

Looking at the Collins Cobuild Dictionary definition just now, I see it reads: ‘You use by the same token to introduce a statement that you think is true for the same reasons that were given for a previous statement.’

That explains its appearance on the Kitchen Cabinet perfectly. The example Cobuild gives reinforces it:

If you give up exercise, your fat increases. By the same token, if you expend more energy you will lose fat.

What surprised me is that Cobuild doesn’t label it ‘formal’, nor does the Oxford online dictionary. Hmmm. Perhaps it’s not formal as such, merely that it’s not often in conversation that one refers back so self-consciously to a preceding statement or argument.

Whatever the truth of the matter, it made me wonder how old the phrase is. It turns out to be a lot older than I would have guessed.

The word token is Old English (as tác(e)n) and related to Modern German Zeichen and Danish tegn. In the OED it first appears in Bede and King Ælfred’s translation of Pastoral Care.

The OED records the phrase first in the Paston Letters in 1463:

And to þis [course] Maister Markham prayed you to agre by þe same token ye meved hym to sette an ende be-twyx you and my maisters your brethren.

Such a long lineage and still going strong!

But my interest was even more piqued because of another idiomatic phrase I was asked in my test to define and contextualise: in the van.

The van we’re talking about here is of course a shortened form of vanguard, and ‘to be in the van’ of something such as a political or artistic movement means to be at the forefront of it, as we would more commonly say. Dutifully, I will have put down my definition and example. They must have worked, because I got the job.

Collins Cobuild doesn’t define the phrase. Which perhaps makes sense because it’s somewhat archaic or precious, I’d say, and not terribly common (Cobuild is systematically based on frequency). Oxford Online gives the definition 1.1. ‘the forefront’, and its first example is ‘he was in the van of the movement to encourage the cultivation of wild flowers.’

Now, archaic, precious, or whatever the phase may be, the Collins test turned out to be a test of how deeply one knew one’s own language, which in effect meant how attentively and widely one had read.

This was brought home to me years later. Riffling through mountains of old files before we consigned them to the great forest in the sky, I found previous failed applicants’ tests.

Among them was: ‘Tell the boys to load it in the van.’

** ‘Yonks’ is very British, I know, but I have to use it. It’s such a great word and one I’ve loved since adolescence – its as well as mine.

November 28, 2024

Lessons from the book of life

(5-minute read – and worth every second)

During the final rallies of her election campaign, US presidential candidate Kamala Harris drew on one metaphor time and time again. She said she was determined, or she saw a nation determined, ‘to turn the page on hatred and division’.

It’s an effective rallying call. It certainly sounded positive, inspiring even. But what can it possibly mean, literally? A page of what?

It’s a metaphor, of course. And the underlying metaphor is ‘life is a book’. How does that work?

Well, definitions of metaphors in language generally suggest we use them to describe person or object A in terms of person, animal or object B because A and B are similar in some way. ‘He’s a bit of a mouse’, ‘means’ he’s so shy he practically scurries away, like a mouse, when he sees someone. So far so good. But where’s the resemblance between a book with its cover, spine, dust jacket, and pages, and life?

There’s no obvious similarity, objectively speaking. If you think about it for a moment, ‘life’ is an ungraspable abstraction, while a book (for the purposes of this discussion) is a highly concrete physical object. When we speak about life as a book we’re using what’s called a ‘conceptual metaphor’, and ontological conceptual metaphors enable us to speak about abstracts it might otherwise be difficult, if not impossible, to describe.

Turning the pageThe similarities don’t objectively pre-exist prior to the metaphor, but thanks to the metaphor people begin to see similarities which certainly shape not only how we talk about life but also how we think about it, how we conceptualise it. Thanks to the conceptual metaphor we can now refer to different periods of our lives as chapters, Kamala Harris could talk about turning the page, and anyone who has a change of heart can turn over a new leaf.

And once the conceptual metaphor is established in our minds, we build on that to imagine and actively create similarities. The Cobuild Dictionary notes a chapter can refer to a period in someone’s life or in the history of a country or institution. This wide coverage lets people elaborate the linguistic metaphor in colourful ways. Remember, a physical book has chapters. So, in examples I’ve gleaned from the Collins Corpus, we talk about the end part of life, a career, etc. as a closing chapter (‘Her final days in a rest home in London marked the closing chapter’). Conversely, a different phase of life can open the next chapter or a new chapter (‘We are entering the next chapter of the financial crisis’). In those cases, it’s still possible to have the physical book in mind, as it is when we talk about something being a closed book, in its meaning of a matter resolved beyond all doubt and one not to be reopened (‘reopened’ is also a hidden book metaphor): ‘I know the past is a closed book, but she doesn’t.’

And metaphorical chapters can be dark or triumphant, painful or glorious, sorry or remarkable, none of which you’re likely to apply to a physical chapter, so they’ve now become absolute metaphor.

He’s an open bookThe ‘life is a book’ metaphor isn’t the only one to draw on books. You and I can be a book too, in answer to the conceptual metaphor ‘people are books’. Hard to believe? Well, people can be animals (‘Don’t be beastly!’ ‘What a pig!’ ‘You gannet!’), so why not go two steps and beyond down the Great Chain of Being to inanimate objects?

We may describe someone as an open book and we’re using that same metaphor when we talk about someone being easy or hard to read, or reading someone like a book. Some people are closed books (‘You’re a closed book. Whatever is going on behind those crinkly eyes, you never let on’) so that closed book metaphor has a dual application: to life, as mentioned above, and to people.

When we jokingly say Don’t judge a book by its cover, it’s that ‘people are books’ metaphor again. In addition, it makes use of another conceptual metaphor, ‘generic is specific’, that is, this specific ‘book’ aka person applies to everyone everywhere.

Some conceptual metaphors cross languages. For instance, ‘anger is hot fluid in a container’ (‘He was fuming’, ‘Smoke was coming out of her ears’, ‘Don’t blow a gasket!’) has parallels in languages as diverse as Chinese, Hungarian, Zulu and Tahitian. What about people as books?

I believe in Danish you can say ‘I can read you like a book’ (Jeg kan læse dig som en bog) and you can say ‘like an open book’ (som en åben bog). Spanish speakers can describe someone as (como) un libro abierto, (‘(like) an open book’), Italians talk about people being un libro aperto or un libro chiuso, with the same meaning of candour and being able to understand at a glance what a person is like, on one hand, or taciturnity and inscrutability on the other.

However, when it comes to Don’t judge a book by its cover, the lexicographical truism that an idiom in one language mostly doesn’t translate word for word into another comes true. As also that the other language might not use a proverb at all. French, Spanish and Italian all have proverbs influenced by their religious past that mean literally ‘the habit doesn’t make the monk’, L’habit ne fait pas le moine, El hábito no hace al monje and L’habito non fa il monaco, respectively. But do people use them as much we use the English? In French you’re more likely to say (Il ne) Faut pas se fier aux apparences and the Collins Spanish Dictionary has a similar paraphrase, no hay que fiarse de las apariencias as well las apariencias engañan, ‘appearances can be deceptive’. The Jewish sage Rabbi Meir said, ‘Do not look at the flask [of wine] but what is in it.’ And the Arabic Almdaher khadda’ah, means, guess what? ‘Appearances can be deceptive’.

Finally, I’ll leave it to you, dear readers, to ponder whether taking a leaf out of a person’s book relates to ‘life is a book’, ‘people are books’, or something else.

NB: This is a transcript of a post by me commissioned by Collins Dictionaries and posted on their website here.