Jeremy Butterfield's Blog, page 7

October 5, 2021

Derevaun Seraun

A fascinating story of (over)interpretation by critics, analysed by an Irish-language expert.

‘As is always the case with Irish, the anglophone world is never slow to project all kinds of ridiculous fantasies onto our language.’

‘… I think he was spot-on when he said that the phrase was ‘probably gibberish’. It’s meant to sound Irish without meaning anything. It suggests Irish but leaves the whole thing open to interpretation. I imagine that Joyce chose these meaningless Irish-sounding words very carefully, knowing that a tantalising puzzle with no solution would have critics of his work swarming all over it like flies on shite.’

This is a question I have been meaning to deal with for a while. It was never discussed by Cassidy but it is of some interest.

Derevaun Seraun is a phrase found in Joyce’s Dubliners story Eveline. It is uttered by a dying old woman, the mother of the eponymous Eveline.

There is no doubt that it sounds Irish and some people claim to hear some clear message in it. As a fluent Irish speaker, do I hear anything Irish in it? Well, I have to admit that when I say it to myself, I do find Irish words in it. I hear (in a Munster accent) the words dearbhán saothrán. Dearbhán means a voucher, as in a card exchangeable for a certain amount of money in a bookshop or a restaurant and saothrán means a culture, specifically a culture of bacteria or fungus on a Petri dish.

Neither of…

View original post 447 more words

September 29, 2021

To intend doing or to intend on doing? Which is correct?

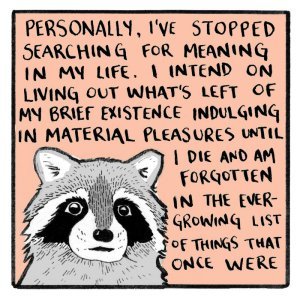

The other day a tweep – well, actually a renowned linguistics Professor – tweeted a cartoon including the frame shown below:

I agree with the sentiments but not the phrasing.

I agree with the sentiments but not the phrasing.Note that structure: ‘I intend ON living out what’s left of my brief existence…’

Shurely shome mishtake, I thought. Presumably a one-off.

But no, it’s not a one-off. More than that: it seems to be really quite common, especially, of course, in that hotbed of solecism ( ) the US.

) the US.

It’s been discussed on WordReference.com. A French speaker raised the issue there and was advised (sigh) by a Canadian TEACHER (double sigh) to use ‘intend on + –ING’, which was then marked wrong by their teacher. Whereupon, depressingly, others opined about the niceties of using intend on + –ING without quite twigging that IT IS PLAIN WRONG according to long-established syntax.

It is also covered in the comprehensive list of errors (also published as a book Common Errors in English Usage) of Professor Paul Brians.

So, is it ‘acceptable’?It’s non-standard. But that doesn’t stop it being quite frequent. (Rather like ‘hone in on’.)

As any dictionary or grammar will tell you, to intend can be followed by one of two structures: a to-infinitive or an –ING form. It’s one of those verbs that allow both forms with no difference of meaning (cf. to like doing/to do, bother…, start…, begin…, continue, etc.)

If I come across it in something I’m editing, should I change it?Up to you. But unless it’s part of a dialogue in the mouth of a character who uses non-standard or colloquial forms, some people will consider it wrong. Also, it depends, of course, on whether your editing style is to implement changes or merely notify the author about something you consider to be amiss.

How did it come to be?There’s a complicated theory and an easy one. The complicated one, which is mine, runs like this:

The adjective intent is used in the structure to be intent on doing something, i.e. to have a very strong desire and intention to do it, to be determined to do it. Its meaning thus overlaps with that of the verb to intend.

Somehow, at some stage people who said/wrote ‘to intend on doing something’ must have muddled the two structures up. It’s not obvious how, though.

‘Intent on’ usually has the verb ‘to be’ before it, so e.g. am/is/are/was/were intent on going. However, the t/d alternation is a fertile source of mistakes in English in eggcorns such as centripedal and mood point, so perhaps that’s the root of the problem. Take the phrase ‘I’m intent on going’, let that last t of intent be interpreted as a d and we get ‘I’m intend on going’. In rapid speech, I suppose that could be interpreted as ‘I intend on going.’

Convinced?

No, me neither, but I can’t work out how it could have happened otherwise. The easy answer, as suggested by Prof. Brians, is that the structure has been influenced by to plan on +-ING. That sounds very plausible to me. Regularisation of patterns seems to be a motor of language change/variety.

Perhaps it’s a mixture of those two factors mentioned.

Do let me know if you have – as I’m sure you will – any better suggestions. But anyway, the fact is that once the pattern started, thanks to the ubiquity of online writing and the ubiquity of ignorance it seems to have spread like wildfire.

It’s non-standard, but is it used a lot?Surprise, surprise. Yes! Three corpora consulted throw up these proportions:

Collins Bank of English (2012; 3 billion 670 million words, 4 billion 417 million tokens)intend.* on .*ing = 658

intend.* .*ing = 10,384

So, of the total of both occurrences, 5.95 per cent are the non-standard, which surprised me…until I looked at the next two corpora.

Oxford New Monitor Corpus (April 2018; 7 billion 980 million words, 9 billion 286 million tokens)intend.* on .*ing = 4,926 = 48.1 per cent. Even more of a shock!

intend.* .*ing = 5,315

Well, that certainly changes the picture and helps explain how the French speaker mentioned earlier was told intend on +-ING was correct – by a teacher, to boot.

Brigham Young Corpus of Web-Based English(A measly 1.9 billion words from 20 countries)

These results are not dissimilar to the previous, shock, horror!

intend.* on .*ing = 606 or 42.85 per cent

intend.* .*ing = 858

Looking at the raw figures for US/Canada/UK gives us the following:

intend.* on .*ing 122 | 55 | 105

intend.* .*ing 41 | 10 | 172

In other words, in this corpus, US and Canadian speakers PREFER intend on +-ING.

At this point, it’s time to give up. Open the gates to the barbarians and welcome them in. Give them alot [sic] to eat and drink…in fact, a feast, a banquet, a surfeit. Reassure them that whatever twisted utterance they come out with is perfectly correct. I jest, of course—somewhat.

No doubt it won’t be too long before ‘the dictionaries’ record this and give it the green light.

As a footnote, in a poll on Twitter in which I asked if people (when editing) would change intend on keeping, 30 per cent said they wouldn’t. Which doesn’t, of course, tell me why they wouldn’t. Except that one person told me it’s ‘colloquial and common’ in the US.

September 22, 2021

Is the autumn equinox the start of a new season? – Collins Dictionary Language Blog

With the autumn equinox happening this week, we look at when precisely the new season begins.

Source: Is the autumn equinox the start of a new season? – Collins Dictionary Language Blog

July 13, 2021

There are metaphors and there are metaphors (2) – as creatively extended by Val McDermid vs the bog-standard metaphors we all use

In last week’s post I did a sort of mini Bluffer’s Guide to conceptual metaphor. (If those at the back of the class need their memories refreshed, please follow this link.)

Now, a claim that one strand of conceptual metaphor theory also makes is this: literary metaphor, far from being uniquely creative, makes widespread use of standard conceptual metaphors but does something rather special with them, such as extending or elaborating them.[i] For example, even Dante’s famous

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

Mi ritrovai per una selva oscura

Ché la diritta via era smarrita

(‘Midway upon the journey of our life |I found myself within a forest dark, | For the straightforward pathway had been lost.’ [Longfellow’s version, courtesy of Project Gutenberg])

is nothing more nor less than an example of the LIFE IS A JOURNEY conceptual metaphor with the novel twist of the selva/forest thrown in. Which is a case of the entailments I mentioned, in this case from the source domain of real, physical journeys where you might get lost and end up in a ‘forest dark’. What Dante has done here is to extend the basic conceptual metaphor by adding the forest.

How artists extend or elaborate conventional metaphors was brought home to me forcefully and repeatedly while reading a detective novel Broken Ground[ii] by the inestimable Val McDermid.

In particular, it is animal-related metaphors that mostly caught my attention. I also include similes on the basis, as one author puts it, airily ignoring the oceans of ink spent on distinguishing similes from metaphors, that a simile is ‘a metaphor with the scaffolding still up’.[iii]

Several of the images both extend a conventional linguistic metaphor and acknowledge an underlying conceptual metaphor. In the hands of a creative writer I imagine such wordplay just flows unhindered from the metaphorical pen. That is one vital aspect of creativity: to take an existing form and refashion it.

The novel’s protagonist is the feisty DCI Karen Pirie, based in Edinburgh.

1. Two upper-middle-class Embra women, Dandy and Willow, discussing Willow’s violent husband, are confronted by Karen, who has overheard their (staged) conversation.

‘Dandy pushes her chair back, recoiling from this harsh truth, shock rearranging her face. But Willow became still as a cat watching prey.’ p.22

English makes use of dozens of feline metaphors and similes. The one acknowledged here is ‘to play cat and mouse with someone.’ At its simplest level that exemplifies the conceptual metaphor PEOPLE ARE ANIMALS, specifically WOMEN ARE FELINES (cf. sex kitten, cougar). It is also an example of the conceptual metaphor (my interpretation) HUMAN VICTIMS ARE ANIMALS’ VICTIMS (to rub sb’s nose in it, to lick your wounds, etc.).

2. DCI Pirie has taken over a case from a local male detective inspector, Wilson, who is not best pleased.

‘He’d pushed back the hood of his well-filled Tyvek suit and his white hair stood out in a halo like a red-faced Albert Einstein. “DCI Pirie, I presume?” he demanded, thrusting his head forward like a farmyard rooster staking out his hens.’ p.94

Here what is being referenced is the pecking order idiom, which depends on the conceptual metaphor (my interpretation) HUMAN HIERARCHY IS ANIMAL HIERARCHY (top dog, underdog, to rule the roost, etc.)

3. Wilson is later very put out by the fact that the body in the case will be wheeched off to Dundee for forensic investigation:

‘“I’m not comfortable with letting the body disappear down the road where we’ve got no input into what’s going on.” Wilson’s prickles were fully extended again.’ p.105

‘Prickles’ picks up on the metaphor of someone being prickly but goes beyond that by mentioning metaphorical (physical) prickles. The underlying conceptual metaphors are ANGRY HUMAN BEHAVIOUR IS DANGEROUS ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR and AND ANGRY PEOPLE ASSUME PARTS OF ANIMALS’ ANATOMY (makes my hackles rise).

4. After an altercation, DCI Pirie’s colleague jokes ‘ “Another name to add to the Christmas card list.”’

‘Karen pulled a face. “I’m not here to make friends. I can’t be doing with all that pissing up lampposts business. Murder isn’t territorial.” ’ p.105

This sounds like an original metaphor – at least it’s new to me and not mentioned in any idioms dictionary I’ve consulted. It plays to the fact that dogs assert their dominance over other dogs and mark their territory by urinating. As in 2, the conceptual metaphor is HUMAN HIERARCHY IS ANIMAL HIERARCHY.

The same colleague picks up the image much later when DCI Pirie wonders why her boss is so down on her.

‘“She’s one of those women who see other women as a threat?” Karen hazarded.’

‘“Maybe. But that’s not what this is about. This is dogs and lampposts. She wants control of HCU [Karen’s unit]. And that means ownership. […] She wants you out.” ’ p.221

5. A detective planted in Karen’s unit by Karen’s boss to spy on her has a bruising encounter with said boss.

‘For a fleeting moment, he wondered whether he’d backed the wrong horse in a race he hadn’t even known was being run.’ p.138

‘Backed the wrong horse’ references the pervasive conceptual metaphor LIFE IS A GAMBLING GAME (they’re bluffing; if you play your cards right, etc.) and the widespread use of horse-racing metaphors (horses for courses, under the wire, inside track, etc.) What Val McDermid has done here, though, is to extend and thereby re-animate the metaphor by mentioning an aspect of the source domain (in other words, made use of a ‘metaphorical entailment’) that is usually latent: that there is a physical race being run.

6. Later, Karen cannot believe that someone has no sinister motive in wanting to have dinner with her.

‘Or had she become jaundiced by the job? Had she grown so underexposed to the milk of human kindness that she didn’t trust it when someone poured her a glass of it?’ p.266

If a metaphor can be truly dead and buried, surely ‘milk’ in this Shakespearean idiom is. Yet it is brought to life here by activating an entailment from the source domain of physical milk: it can be poured into a glass.

7. My last example takes a rather clichéd metaphor and again springs a surprise on the reader by activating an entailment from the source domain. A former banker – and, potentially, Karen’s love interest – explains what happened in his bank when the global financial crash happened.

‘ “All around me people were being fired. They were literally staggering out of the office like they were drunk. They couldn’t believe their personal gravy train had walloped straight into the buffers.” ’ p.270

The underlying conceptual metaphor is A CAREER IS A JOURNEY and extension of the metaphor consists in two things: first, specifying the vehicle for the journey as a train, in this case ‘the gravy train’, and second, taking from the source domain the knowledge usually never activated in metaphors, that trains are stopped by buffers. Compare to hit the rails, to go off the rails.

Whatever you happen to be reading at the moment, I wonder how many animal metaphors it will contain. I bet there will be a few.

[i] Kövecses, Z. (2010). Metaphor A Practical Introduction (2nd edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press, Chapter 4.

[ii] McDermid, Val. (2019) Broken Ground [2018] (pback edn). London: Little, Brown Book Group.

[iii] Geary, James. (2011). I Is An Other: The Secret Life of Metaphor and How it Shapes the Way We see the World. London: HarperCollins Publishers, p.8.

July 12, 2021

New Conversations Day – Collins Dictionary Language Blog

My thoughts on ‘conversation’ as in New Conversations Day.

Collins Rubric: ‘With 12th July being New Conversations Day, we look at the lingo around conversation, chatting, and different terminology for talking around the world.’

Source: New Conversations Day – Collins Dictionary Language Blog

June 30, 2021

There are metaphors and there are (conceptual) metaphors and there are (animal conceptual) metaphors

The more I think about it – and I’ve been thinking about it for quite a while – the more fascinated I am by conceptual metaphors. And the more convinced that they are psychologically real.

Say again?In the words of a leading expert:

‘Metaphor is not simply an ornamental aspect of language, but a fundamental scheme by which people conceptualize the world and their own activities.’[i]

You’ll know the idiom this illustrates. Clue: joy.

You’ll know the idiom this illustrates. Clue: joy. Image courtesy of fancycrave1 on Pixabay.

Take the idioms connected with the idea that ‘life is a journey’: He’ll go far, to get a good start in life, I’m at a crossroads and so forth.

Metaphors in general come about through ‘understanding one conceptual domain in terms of another conceptual domain’.[ii] And conceptual metaphor theory states that conceptual domain A is conceptual domain B. In the life is a journey metaphor, life is the ‘target’ domain and is written first and journey is the ‘source’ domain and comes second. It is conventional to use small capitals, i.e. LIFE IS A JOURNEY (but I can’t do small caps in WordPress!).

By means of conceptual metaphors, typically we understand and verbalise what is abstract – especially emotions – in terms of what is concrete. Thus, love is a journey (we’ve reached the end of the line), life is a journey, again (where do you want to go in life?), an argument is a journey (we’ve covered a lot of ground) and so forth.

One crucial function conceptual metaphors perform is to enable us humans to understand, frame, describe and even experience things – especially emotions – in ways that we and other people can understand. For instance, how to describe anger, a much-discussed emotion in the conceptual metaphor literature?

If looks could kill…

If looks could kill…Image courtesy of Pixabay, OpenClipart-Vectors.

Describing extreme anger

I was fuming.

You blew a gasket.

He blew his stack.

She literally exploded.

They hit the roof.

This little conjugation of ire might seem like a random collection of English idioms to do with fury. But have you ever asked yourself why these particular and very specific images?

Underlying and connecting them all are several conceptual metaphors: the source domain is our body and the conceptual metaphors are that OUR BODIES ARE CONTAINERS; that OUR EMOTIONS ARE (substances) LIQUIDS inside these containers; that the (substances) liquids can be heated (or frozen); and, specifically, that ANGER IS HEATED LIQUID INSIDE A CONTAINER capable of causing that container to explode when the liquid (i.e. the anger) reaches a certain temperature (intensity). In all of these conceptual metaphors, ANGER is the target domain.

Metaphorical entailments

Source and target can often be connected by what are known as ‘metaphorical entailments’. For example, in the case of ANGER IS HEATED LIQUID INSIDE A CONTAINER, we apply many facets of what we know about the physical properties of heated liquids to the target domain of ANGER. We know that heated water can produce steam, so we talk of someone getting all steamed up. We know also that a heated liquid can cause a container to burst or the top to come off, so we say he flipped his lid.

As another granddaddy of conceptual metaphors notes, ‘Emotions are often considered to be feelings alone, and as such they are viewed as being devoid of conceptual content.’[iii] But the opposite is the case: conceptual metaphors help us think about and give voice to otherwise inexpressible and ineffable sensations.

Here’s a thought experiment: think of the last time you were very, very angry. How would you describe it?

Now, try doing it without recourse to metaphors.

Who’s a nice doggy, then?

Who’s a nice doggy, then?Image courtesy of GemmaRay23 on Pixabay.

One key ‘source domain’ for conceptual metaphors is the animal kingdom. So far, I’ve amassed well over 1,000 in relatively common use. I’ve blogged elsewhere about how ‘it’s a dog-eat-dog world‘ has been eggcornised to ‘it’s a doggy-dog world’ and about animal similes for people being fit.

[i] Gibbs, Raymond W. Jnr. (2008). In: Gibbs R.W. Jnr. (ed.) Cambridge Handbook of Metaphor and Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p.3.

[ii] Kövecses, Z. (2010). Metaphor: A Practical Introduction (2nd edn). Oxford: Oxford University Press, p.4

[iii] Lakoff, George. (1987). Women, Fire and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind. Chicago: Chicago University Press, p.380.

June 1, 2021

Say Something Nice Day! – Collins Dictionary Language Blog

A bit late in this National Say Something Nice Day, but…better late than never.

I hope you’ve had a good one and have a lovely evening.

Yours truly’s thoughts on the matter are in this Collins blog.

With Say Something Nice Day on June 1st, we look at what we can say and do to make someone happy in our everyday interactions.

Source: Say Something Nice Day! – Collins Dictionary Language Blog

May 24, 2021

Road map or roadmap. One word or two?

Short answer: both are ‘correct’ but usage seems to be shifting in favour of the single-word form.

Image by Dewald Van Rensburg from Pixabay

Image by Dewald Van Rensburg from PixabayI’m updating this post almost a year to the day after I first posted it. And guess what? That tired old cliché of roadmaps is still haunting us. If I go to the UK government website, I find this statement: ‘Planned easements at Step 3 of the Roadmap to go ahead from 17 May’. As for ‘easements’, we’ll come back to that unintentionally comical word lower down.

A year and a bit ago now, on 11 May 2020, the UK government put before parliament its plan for the way out of Covid-19 restrictions.

In the 50-page document, roadmap (spelled thus, as one word) appeared no less/fewer than seven times.

The Scottish devolved administration, however, spelled it as two words last year. This year the tartan politburo prefers the phrase ‘route map’. Anything to make on it is doing something different to the rest of the UK, yawn mega yawn.

But back to the matter in hand: between road map and roadmap, which is correct?

Well, obvs, both. If you look in the dictionaries – Oxford Online, Collins, Cobuild, Merriam–Webster, Webster’s New World College, Oxford Advanced Learner’s, Cambridge – you will find it typeset as two words. But here’s the thing. Words like this with a space between their two elements are what is known as ‘open compounds’ while roadmap and its ilk are ‘solid compounds’. Over time, almost like old couples, open compounds merge into solid ones.

It’s a historical process that has happened repeatedly. When Jane Austen wrote any body she did not mean ‘any old cadaver’; body in her sense meant ‘person’:

“It is very pretty,” said Mr. Woodhouse [sc. to Emma]. “So prettily done! Just as your drawings always are, my dear. I do not know any body who draws so well as you do.

When the great humanist Roger Ascham expressed his views on education, he wrote in deed, as was common, says the OED, until 1600 or thereabouts:

The Scholehouse should be in deede, as it is called by name, the house of playe and pleasure.

a1568 Scholemaster (1570) Pref.

Other examples going further back in time are alone (all adverb+one), although (all adverb+though) and albeit (all conjunction+be+it.) An analogous process produces the frowned-on *alot for a lot. The people who write it as a single word clearly perceive it as a unit of meaning in its own right and not dependent on the meaning of lot.

Someone on Twitter suggested that the road map spelling refers to the physical object and roadmap to the figurative meaning. It sounds vaguely plausible, but the only similar duo I can think of is black bird/blackbird, a distinction which is rather different.

In any case, the literal meaning is nowadays pretty rare (satnav rules, OK!) and searches in corpora show that each of the two forms is used for both literal and figurative meanings.

In an up-to-date corpus of 20 varieties of English, roadmap is about twice as common as road map. In a corpus built in 2104, the two forms were even-stevens, just about, but by the time of a 2018 corpus the ratio was 3:1 in favour of roadmap.

So, editors might be in a bit of a quandary if they come across road map. Should they change it to roadmap? The safest bet would be to raise it with the author and point out that the dictionaries are behind the curve on this one. I have it on good authority that the next Macmillan revision will change to roadmap. At the moment, Macmillan offers the solid form as an alternative to the open compound.

Meanwhile, let’s see how long we wait before most dictionaries mirror this new reality.

As for easements in Step 3 of the Road Map … it is probably just my scatological turn of mind that reminds me that the Tudor lard-arse Henry VIII built a magnificent Great House of Easement at Hampton Court capable of accommodating 28 of the lower orders for the relief of their bodily functions.

Oxford Online gives the word two meanings in current use, one being a legal right to cross or use someone’s land for a specified purpose, the other being a state of comfort and ease. Collins multiple offering says much the same while adding an architectural meaning. Merriam-Webster echoes Oxford.

Why relaxation, alleviation, or some similar word was not chosen, heaven knows. Perhaps some mandarin, policy wonk or spad has a wicked sense of humour.

May 19, 2021

Honey catches more flies than vinegar (2). A Pan-European proverb? On prend plus de mouches avec une cuillerée de miel qu’avec cent barils de vinaigre; Más moscas se cogen con miel que con hiel

‘Why is he blogging about this obscure proverb again?’ you might be asking.

5-minute read (but read carefully!)

The answer is: because it’s a mystery. Versions exist in several languages, a fact which suggests a common origin, perhaps in Latin, or even Greek, as is the case with many proverbs. That led me to channel my inner Sherlock. However, though I tracked down a couple of Latin versions, they look more like back-translations from the vernacular. Which raises the possibility that it just spread from one vernacular language to another.

Image by Gabriel Manlake on Unsplash

Image by Gabriel Manlake on UnsplashCuriouser and curiouser, to coin a phrase. I deal with all that in the second part of this post.

Meanwhile, in the previous post about ‘Honey catches more flies than vinegar’ I said it seems to have passed into English from Italian in the third quarter of the seventeenth century. The person who first put it in print, Giorgio Torriano, I therein called ‘an Italian teacher’. That description rather sells him short. Perhaps ‘pedagogue’ would be sufficiently grand and accurate (but without the negative connotations that can cluster round the word.) For not only did he collect and publish proverbs – which merely requires a train-spotting bent of mind – he also wrote grammars of Italian for his audience.

Learning Italian in the UK is nowadays a minority pursuit. In contrast, in the late sixteenth century to know Italian was an important weapon in the intellectual armoury of the elite: Lady Jane Grey, Queen Elizabeth and James VI and I’s consort, Anne of Denmark, all knew la bella lingua. John Florio, the author of the first substantial Italian-English dictionary, was a groom of Queen Anne’s chamber and enjoyed a position at court. Torriano inherited Florio’s manuscripts and in 1639 published New and Easie Directions for attaining the Thuscan Italian tongue and the year after that The Italian Tutor.

The volume from which ‘Honey gets more flyes to it, than doth viniger’ was Torriano’s 1666 Piazza universale di proverbi Italiani, or, A common place of Italian proverbs and proverbial phrases digested in alphabetical order which provides the OED with a few dozen citations. One of them includes the first citation of the piquant idiom ‘His father was born before him‘, meaning he inherited wealth: The English something to that purpose say, of a rich man that never purchas’d his Estate, His Father was born before him.

Nowadays we might be tempted to think of proverbs as trite or clichéd and even take fully to heart Orwell’s injunction: ‘Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.’1 But in Florio and Torriano’s day they were considered the summit of human wisdom. So much so that Florio included a staggering six thousand Italian proverbs in a supplement called Gardine of Recreation to his second Italian-teaching work Second Frutes.

The naughty-schoolboy-in-me-looking-up-rude-words-in-the-dictionary could not resist another Torrianism. Apparently, according to the OED, there was a phrase cricket-a-wicket cited only from Florio in the OED and meaning a bit of how’s your father. Torriano records this in a garbled form as ‘fare frit frit, to play Cricket, a cricket, to make the bed cry, jigga-joggy.’ An interesting use of the reduplicative possibilities of English. And fare frit frit has a ring to it.

Does the proverb exist outside English and Italian?Yes, very much so. Read on.

As it happens, the Italian version which Torriano used is not recognised today. Il mele catta più mosche, che non fà l’aceto contains elements of dialect such as mele for miele while cattare meaning ‘to take’ has fallen out of use. The writers at an Italian Word of the Day site assured me that the modern version would be Si prendono più mosche con una goccia di miele che con un barile di aceto, (‘More flies are taken with a drop of honey than with a barrel of vinegar’) with variations in the verb and the quantities of both honey and vinegar. It gets over 100K hits on Google, not all of which are from dictionaries or in some other way metalinguistic. Those hits show the aforementioned variations in the verb (pigliare, acchiappare).

In the previous post I mentioned that seventeenth-century French had l’on prends plus de mouches avec une cuillerée de miel qu’avec cent barils de vinaigre (‘…with a spoonful of honey than with a hundred barrels/casks of vinegar’).

The body responsible for promoting the Spanish language, the Instituto Cervantes – the equivalent if you like of the British Council – has a multilingual idiom collection. According to it, French has on prend plus de mouches avec du miel qu’avec du vinaigre. Searching for this on Google, however, suggests it was the original formulation but that nowadays it has many variants, such as on ne prend pas les mouches avec du vinaigre. Those are the only two forms listed in the Trésor de la Langue Française.

Spanish has the same proverb:

Más moscas se cogen con miel que con hiel

(‘more flies are caught with honey than with bile’).

Given the taboo nature of coger in Latin America, there are variants such as se atrapan, se cazan and so forth, as well as in the quantities, as happens in Italian.

According to the Cervantes file, the expression exists in exactly the same form in Portuguese, Galician, Basque and Catalan. It also exists in a similar form in Greek: Περισσότερες μύγες πιάνεις με το μέλι παρά με το ξίδι (literally ‘more flies you catch with the honey than with the vinegar’).

The exception here seems to be German with its pork addiction: Mit Speck fängt Man mäuse (‘with ham you catch mice’).

Danish seems to have the more widespread version: du kan fange flere fluer med honning end med eddike (‘you can catch more flies with…’ the usual suspects)

Is there a Latin source?The spread across languages made me wonder if there was a common Latin source.

It seems not – probably.

The only Latin I could find by Googling plures muscæ captantur (at a guess) retrieved aceto non captantur muscæ (‘with vinegar are not captured flies’), not classical, chronologically speaking, but from a Latin article by an eminent Dutch philologist in an academic journal of 1891. I presume it to be an on-the-spot translation back into Latin. But if so, then from which language? Dutch is the logical answer. And whadya know!

There in Dutch (so the Interweb informs me) is je/man vangt meer vliegen met (en lepel) honing/stroop dan met (en vat) azijn.

‘You/one can catches more flies with (a spoonful) [of] honey/syrup than with (a barrel) [of] vinegar.’

I can’t say how common it is, but the existence of Delft tiles (whether real or virtual I am not sure) suggests a certain spread.

But the plot thickens.

I then tried changing the Latin verb to capiuntur and lo and behold I get two hits on Google for melle, non aceto muscæ capiuntur, which means, guess what, ‘with honey not vinegar flies are caught.’

Those two citations come from the 1794 work of an eighteenth/nineteenth-century Croatian Latinist Georgius Ferrich (1739–1820) and prefaces one chapter (XXXI/31) in a collection of 113 Latin fables derived from Croatian (Fabulæ ab Illyricis adagiis desumptae, ‘Fables Selected from Croatian Proverbs’). The Croatian epigraph of the fable is Medom-se, ne ostom muhe hittaju, which is followed by melle, non aceto muscae capiuntur, meaning what you’d expect it to by now.

Job done for today. I can go home.

1 Orwell, George (1946). Politics and the English Language. http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks02/0200151.txt Accessed 17 May 2021.

References

“born, adj.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2021, oed.com/view/Entry/21674. Accessed 17 May 2021.

“cricket-a-wicket, adv.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2021, oed.com/view/Entry/44392. Accessed 17 May 2021.

“honey, n. and adj.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2021, oed.com/view/Entry/88159. Accessed 17 May 2021.

Wikipedia, ‘Croatian Latin Literature’. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Croatian_Latin_literature. Accessed 17 May 2021.

Ferić, Đuro. (1794). Fabulæ. Electronic version available at http://www.ffzg.unizg.hr/klafil/croala/cgi-bin/getobject.pl?c.401:2:31.croala.392018. Accessed 17 May 2021.

Ferrich, Georgius (1794) [see previous]. In Corpus Corporum, at Zurich University.

May 13, 2021

Honey catches more flies than vinegar. Background to a proverb (1)

‘I really should get out more often’, in the words of the traditional self-depreciating sign-off by writers of letters to Private Eye that correct some trivial mistake. But lockdown has not yet been entirely unlocked so there isn’t much point. In this state of self-imposed semi-incarceration the thrill of finding a rare proverb being used in a current source is vastly magnified until it’s as intensely pleasurable as that first glug of champagne or the sight of a flaming sunset.

Imagine, then, if you will, my electric excitement upon reading ‘You catch more flies with honey than vinegar and you catch more readers with good prose than bad.’1

More exciting still, if that is possible without the top of my head spinning right off, is what a bit of research on the jolly old Interweb throws up.

Some proverbs surely most everyone knows, like ‘A stitch in time saves nine’.2 (But then again, I may be making a middle-aged assumption.) Others are less well known but not unknown, such as ‘Half a loaf is better than no bread’. And then there are the vanishingly rare or obscure ones such as ‘There is reason in the roasting of eggs’ (1659, every action has a reason, no matter how bizarre that action seems) and ‘Honey catches more flies than vinegar’ and its variants, meaning, gentle speech and tact achieve more than criticism or reprimand – a truth a certain Home Secretary might be advised to bear in mind. Not to mention gazillions of people on social media.

As with many proverbs, it seems to be an import from another language. In 1666, Giovanni Torriano, a well-known teacher of Italian ensconced in London, published a collection of proverbs titled Piazza universale di proverbi Italiani, or, A common place of Italian proverbs and proverbial phrases digested in alphabetical order. Short titles were clearly not a thing in them days. Included in it was:

Honey gets more flyes to it, than doth viniger

the Italian for which Torriano gave as Il mele catta più mosche, che non fà l’aceto3 (literally ‘The honey catches more flies than not does the vinegar’). Earlier than that, as the OED and The Oxford Dictionary of Proverbs make clear, there was a French version, noted in a 1624 source: souvenez‐vous que l’on prends plus de mouches avec une cuillerée de miel qu’avec cent barils de vinaigre ‘remember that one catches more flies with a spoonful of honey than with a hundred barrels of vinegar’.

That French version is clearly mirrored in the next OED citation, the which4 is only natural, given that the source in question is a translation from French:

A Man catches more Flies with one spoonful of Honey, than twenty Tun of Vineger.

tr. H. de Péréfixe de Beaumont Coll. Brave Actions & Memorable SayingsKing Henry the Great 51

This is tun meaning ‘a large barrel or cask’.

In its ‘standard’ form Honey catches more flies than vinegar is first cited in the OED as being from the 1766 edition of the book that popularised a put-down, The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes, though the phrase Goody Two-Shoes itself is several decades older (1687).

But older than that OED citation is the appearance of the phrase in a work by Benjamin Franklin, in the 1744 edition of his annual almanack Poor Richard:

Tart Words make no Friends: a spoonful of honey will catch more flies than Gallon of Vinegar.

Preceding it was the wise old saw

If you’d lose a troublesome Visitor, lend him Money.

while ‘Make haste slowly’ follows.

Another great American also made use of our vinegary wisdom. In an address to the Temperance Society in 1842, Abraham Lincoln enjoined his listeners thusly,5 adding alliteration into the bargain:

When the conduct of men is designed to be influenced, persuasion, kind, unassuming persuasion, should ever be adopted. It is an old and a true maxim, that a ‘drop of honey catches more flies than a gallon of gall.’ So with men.

The most up-to-date citation in the OED references another great American statesman:

Obama seems to have added honey to his arsenal in dealing with foreign leaders, and the old adage says that honey catches more flies than vinegar.

2009 Austin (Texas) Amer.-Statesman (Nexis) 1 May a10

1. Laura Freeman, ‘Painted Out’, Spectator, 1 May 2021.

2. As regards frequency, in one corpus ‘a stitch in time…’ appeared 33 times, ‘half a loaf’ 27 times and ‘honey catch more flies’ once, in a misquotation of the Lincoln version.

3. A proverb that illustrates two facets of Italian: a) the use of the definite article for uncount nouns being different from English; and b) the use of the ‘pleonastic’ non, which is explained here.

4. It would be a good idea to revive this antiquated English usage: it makes it unambiguous that the reference is to the whole preceding clause.

5. If you are the kind of reader whom thusly made sit up and take notice, that was my intention. Though often derided, thusly is recorded in dictionaries, with or without a label.

References:

“honey, n. and adj.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, March 2021, oed.com/view/Entry/88159. Accessed 13 May 2021.

‘Quote For The Day’, The Atlantic, 11 March 2010. https://www.theatlantic.com/daily-dish/archive/2010/03/quote-for-the-day/189425/ (accessed 13 May 2021).

Freeman, Laura (2021). ‘Painted Out’, Spectator, 1 May 2021. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/why-should-art-have-ever-been-considered-a-male-preserve- (accessed 13 May 2021)