Lording it over – or lauding it? All glory, laud, and honour … Commonly confused words (29-30)

Quick takeaways

Quick takeawaysIf you laud someone, you praise them.

If you lord it over someone, you treat them arrogantly and in a domineering way.

Very occasionally, lorded seems to be used for lauded.

Conversely, and rather more often, laud (in all inflections) seems to be used for lord, which I find more difficult to explain semantically. However, this eggcorn goes back at least to the 19th century.

Perhaps someone can help.

You should be lorded because…

(No, the above is not from a conversation between a member of the government and a Tory party donor.[1])

In a Daily Express online article (ok, I know, I know, an organ that is not necessarily the guardian of the nation’s orthography), my eye was caught by the juxtaposition of a standard spelling and an eggcorn.

In the body of the article, someone was quoted as saying “You should be lauded because you’re wearing uniform, you should be celebrated for wearing uniform.” But the summary box at the side (I don’t know what you call that; somebody will no doubt enlighten me) had “You should be lorded because you’re wearing uniform.”

(Interestingly, when I looked again after a few hours, the mistake had been corrected, possibly by a vigilant sub-editor, if such people still exist)

Inevitably, this set me wondering whether this was a complete one-off, or a more widespread homophone eggcorn. It gets only a passing mention in the main online eggcorn database, so I decided to do a bit of my own linguistic gumshoeing.

Remind us. What’s an eggcorn, again?

In case any gentle readers have forgotten what an eggcorn is, here’s the OED definition: “An alteration of a word or phrase through the mishearing or reinterpretation of one or more of its elements as a similar-sounding word.”

And for those who have forgotten (wake up, you at the back!) what a homophone, as opposed to a homophobe, is: quite simply, it is a word pronounced identically to another one that has a different spelling. The classic case is, of course, the dreaded their/there/they’re.

(For those who wish to pursue the topic, here’s a link to a Grauniad list of homophone confusions.)

Why this eggcorn makes sense

The OED definition misses out a crucial feature of eggcorns: they are not arbitrary or random (in the older sense of that word). The change has to be semantically and grammatically justified — at least in the mind of the eggcorner. So, to take “lorded” being used instead of “lauded”, as in the quoted example: a) the verb to lord exists as part of the phrasal verb to lord it over and is probably part of most people’s vocabulary, so it is a spelling waiting to be appropriated for the “laud” meaning; b) if you use lord as a transitive verb, presumably you are “making someone a lord”, i.e. you are putting them in an exalted position, so that makes sense semantically, and explains the eggcorn. But, was it a hapax? The answer is no.

If you are enjoying this blog, and finding it useful or interesting, there’s an easy way for you to find out when I blog again. Just sign up (in the right-hand column, above the Twitter feed) and you’ll receive an email to tell you. “Simples!”, as the meerkats say. I shall be blogging semi-(ir)regularly about issues of English usage, word histories, and writing tips. Enjoy!

I like being lauded. Who doesn’t?

First, I looked in the Oxford English Corpus. It throws up 1,699 occurrences of lord as a verb. If you filter out the word over in a five-word window either side (on the assumption that, if used with over, lord couldn’t be an eggcorn for laud) that reduces the number by about half (to 841), but a quick scan of those remaining citations did not reveal any as an eggcorn for lauded.

However, a search on Google for be lorded minus “over” (to filter out the passive use of “to lord it over someone”) does throw up a few echt eggcornisms, such as:

“Like many organizational processes, socialization and prestart training may simply be lorded as positive features of the organizations [sic] human resource …”

And in a comment on a Bradford Herald & Argus article of 27 July 2015 about new investment in the city centre:

“Any other city in the country this would be lorded as a big investment and showing confidence in the city.”

So, while rare, this eggcorn is not unique [2].

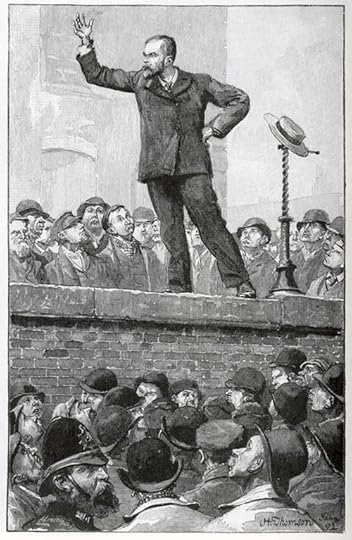

Don’t laud it over me!

A demagogue attempting to “laud” it over a crowd, but not seeming to have much success.

What surprised me, however, is that in the OEC data laud appears to be more often used for lord than the other way round. A search for laud as verb followed immediately by it produced 77 examples, of which 7 were eggcorns, e.g.:

“So confident was Blair of this that he lauded it over his critics , sneering before parliament…”

A Google Ngrams search unearths plentiful examples of the eggcorn this way round, in a wide range of texts, including novels by Catherine Cookson and Barbara Taylor Bradford.

More surprising to me was that this form goes back to the nineteenth century, often appearing in religious tracts of various kinds:

“…that ambitious and seditious demagogues might laud it over the throne, and the aristocracy; and bow the neck of the lordly and the mighty to their unhallowed yolk.”

Truth’s Advocate against Popery and Fanaticism, 1822.

“What has become of your self-complacency? Where the pride and the lauding it over your poor fellow-sinner?”

The Gospel magazine, and theological review. Ser. 5. Vol. 3, no. 1 July 1874

The only explanation I can think of for laud it over in those days is this, but hope someone can supply a better one:

Laud meaning praise is a word used principally in religious contexts;

People in the nineteenth century would have been familiar with it in that context;

If they heard but never read “lord it over”, they would learn it as an idiom, a gestalt, and slot the word they knew – laud – in;

For US writers, lord referring to the aristocracy might not be in their active vocabulary, and this might have helped block that analysis of the phrase.

Convinced? I’m not, but it’s as good a guess as any.

(On the eggcorns forum, a wag has suggested that “perhaps the person ‘lauding it over’ me is singing his own praises so loudly that he can’t hear me?”)

All glory, Lord, and honour

The correct version is, of course, All glory, laud, and honour, to thee, Redeemer, King.

I remember first singing this, with its simple, stirring tune at school. But I have to confess that if I hadn’t been learning Latin and hadn’t seen the words written down, I would have interpreted it as “Lord”. And that is what many people do, as a Google search will quickly show [3].

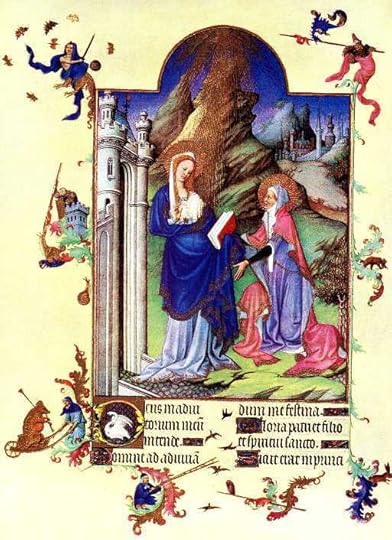

Lauds

From the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. In Books of Hours, a portrayal of the Virgin being visited by her cousin Elizabeth was often placed at the beginning of the section on Lauds.

Lauds is “A service of morning prayer in the Divine Office of the Western Christian Church, traditionally said or chanted at daybreak, though historically it was often held with matins on the previous night.” It is one of the parts of the daily round of prayer: matins, lauds, prime, terce, sext, none, vespers, compline. Auden wrote a sequence of poems about each one (excluding matins) including Lauds, with its sing-song echoic stanza pattern, based on the medieval poetic form, the cossante.

Among the leaves the small birds sing;

The crow of the cock commands awaking:

In solitude, for company.

Bright shines the sun on creatures mortal;

Men of their neighbours become sensible:

In solitude, for company.

The crow of the cock commands awaking;

Already the mass-bell goes dong-ding:

In solitude, for company.

Men of their neighbours become sensible;

God bless the Realm, God bless the People:

In solitude, for company.

Already the mass-bell goes dong-ding;

The dripping mill-wheel is again turning:

In solitude, for company.

God bless the Realm, God bless the People;

God bless this green world temporal:

In solitude, for company.

The dripping mill-wheel is again turning;

Among the leaves the small birds sing:

In solitude, for company.

1 As a transitive verb, to lord can mean to make someone a lord, though this use is archaic.

2 I sometimes wonder if there any totally unique [please don’t tell me I can’t qualify “unique”] eggcorns.

3 Google also showed me a version titled “All glory, praise, and honour”, presumably because laud is such an archaic word.

Filed under: Advice for writers, Confusable words, eggcorns, Grammar, Meaning of words, Poetry, Spelling Tagged: easily confused words, W.H. Auden