Max Carmichael's Blog, page 8

April 22, 2024

Both Near and Far

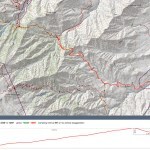

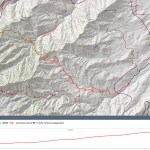

After last Sunday’s bushwhack in Arizona, I needed a hike that was both nearer and in better condition. But since I was still trying to rebuild capacity, I chose the mostly boring hike, twenty minutes from home, that totals 18 miles out-and-back, with over 3,000 feet of elevation gain.

A short drive meant an early start, giving me plenty of time to move slowly and mitigate the impact on my joints, which hadn’t faced anything this long since last September. But the proximity to town and the easy start on a road up a spectacular canyon means this is a popular trail, and within the first quarter mile I encountered an older couple with a dog that looked like a wolf.

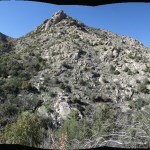

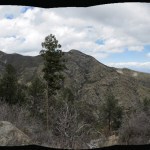

It was chilly in the canyon, but I expected a high in the 70s in the afternoon. I made good time climbing the steep section through the dark forest, out of the canyon to the five-way trail junction at 8,000 feet – the four-mile point. Just past that, on the forested traverse across the next watershed, I stepped aside for a thirty-something trail runner, a guy who’d gone up to the peak with his dog and was returning – a pretty good run at twelve miles and almost 3,000 feet of elevation.

Just below the peak I encountered a forty-something woman wearing a t-shirt from some statewide environmental group. She was perky and immediately asked me where I was coming from, but as I answered it was clear she wasn’t familiar with the area, and she seemed uptight and anxious to move on. She said she’d driven up the road to the crest and was just doing a short hike down this trail.

I’d been avoiding this trail because just past the peak there’s a segment that holds deep snow late into the spring, and I’d brought my gaiters just in case. Sure enough, I needed them – patches were up to eighteen inches deep, and soft enough to sink in.

I was feeling okay, but began to doubt the wisdom of going all the way to the pine park at nine miles. I figured I would pay attention to my body and turn back whenever it seemed right. But it never seemed right. A quarter mile before the pine park I encountered a chubby guy in his 40s or 50s, also with a dog, and it turned out he was the same mountain biker I’d run into last September, using a chain saw to clear logs off the trail so he could ride it. He’d picked the same day as me to return seven months later – how likely is that?

At the park, I stretched out on pine needles to rest, but was quickly swarmed by ants, so I moved to the grassy meadow in the middle, which seemed ant-free. I wasn’t feeling too bad after the first nine miles, but was a little concerned about how I’d feel another nine miles later, after a 3,000 foot descent on knees that had been punished last Sunday.

I recalled the story about the blind men and the elephant. All the people I’d run into on this hike had only seen part of it – as usual, I was the only one who’d covered it all.

And I’d been suffering from allergy all day – surprising because pollen is mostly settled this late in the season. But coming down from the peak I noticed a big alligator juniper completely blanketed in pollen. Apparently our long winter delayed the blooming.

I ended up going slower and slower as my joints began to complain, and in the end, the eighteen miles took me ten hours, including the stops. I ran into yet another hiker with dog shortly before the end. The guy was tall and skinny, but his dog was tiny, and I thought what a tasty morsel it would make for a native predator. This canyon is popular with bears.

Four parties out of five had dogs, and a few days earlier I’d noticed an article in the national media titled “Too Many People Are Getting Dogs”. Something I’ve been saying for years. Most pet owners are irresponsible, and the few who are only encourage others to get them, calling themselves “animal lovers” as our planet becomes more and more domesticated and wild animals and plants suffer and go extinct.

April 15, 2024

Jungle Fighter

You’d think I would’ve learned by now that the twelve-to-eighteen-mile hikes I crave are simply not accessible from January through April. But I guess it will always be frustrating to give those up every winter.

I was so frustrated this weekend that I decided to return to the route I’d hiked over in Arizona only four weeks ago. The trail continues down into a new canyon, and it appeared to have been cleared of brush, so this Sunday’s goal was to reach the bottom of that canyon, adding a thousand vertical feet to the return hike.

The day was forecast to be clear, with afternoon temperatures at the trailhead reaching the 80s. My vehicle’s air conditioning was destroyed when I hit a deer two years ago, and on the back road that leads to the trailhead, it was warm enough already that I had to roll down my side window. There, I was amazed to discover brittlebrush – encelia farinosa, one of my favorite spring wildflowers in the Mojave Desert – covering the foothills.

By the time I hit the trail in the mouth of the canyon at 9:15 am, it was already warm enough that I had to unbutton my shirt. The sweat was dripping off me as I labored up the steep, rocky trail over the shoulder into the tributary canyon. Spring flowers were exploding, but I was discouraged to notice isolated patches of invasive brome grass even within the wilderness study area, which hasn’t been grazed in decades. Other than that, the vegetation here is remarkably wild.

Past the trail junction above the tributary canyon, the dauntingly steep climb to the distant saddle felt as hard as ever. Damp stretches of trail showed the tracks of three hikers who preceded me more than a week ago, two men and a woman. Despite the trail being clear all the way, I had to stop frequently to catch my breath, and it took 3-1/2 hours to go the four miles. As the tributary canyon narrowed, a cool breeze came up and I had to re-button my shirt.

Last time, I’d ventured less than 200 yards on the trail into the new canyon, where as I mentioned above, a trail crew had cut brush. But now I discovered their work ended right beyond the point I’d reached before. Beyond that, the trail was overgrown with shrubs, blocked by deadfall, and in many places the old tread was completely eroded away – all 1,000 vertical feet of it.

I debated turning back, but after a few minutes of that I started pushing through, figuring I would just see how bad it was. The advantage of the brushy overgrowth was that it stabilized the soil, so in overgrown stretches, you could easily follow the old tread. I found myself comparing this with the scrub oak thickets that have replaced mixed-conifer forests near home after wildfires. The scrub oak thickets have very stiff branches, but they only reach chest height, so you can use your torso to force your way through, optimizing your center mass and avoiding scratched hands.

But these Arizona post-fire thickets had long, slender trunks and branches that grew high overhead and arched over the old trail, interlocking from both sides so I had to walk with my arms upraised and head bent forward so my hat would keep the branches out of my eyes. My hands ended up covered with scratches, but since long stretches of overgrowth alternated with clear stretches, I kept going.

My first goal was to round a corner to my left which would give me a view of the crest above, featuring the summit of the range. But when I reached that point, it looked like the canyon bottom was only a few hundred feet below, which encouraged me to keep going.

For the next hour, I pushed my way through thickets, crawled under fallen logs, stepped high over the outstretched branches of deadfall crowns, and inched carefully across steep slopes of loose dirt where the old trail had completely collapsed. One blessing was a scarcity of thorny locust, the scourge of higher elevation burn scars back home, but there was still enough to damage my new shirt and canvas pants.

Switchbacks took me downstream of the point I’d seen from above, and I knew it would be even harder to bushwhack back up from the bottom, but now I was committed.

The old wildfire had almost completely destroyed the mixed-conifer forest on this slope, but as I approached the bottom, where the fire had been slowed by cooler temps and higher humidity, I finally entered intact forest, and soon I found myself on a grassy bench. Below lay a broad debris field which had been colonized by post-fire trees and shrubs. I had to pick my way through more thickets and deadfall, stepping precariously over the boulders in the debris flow, while somewhere beyond, the stream was roaring, still unseen.

On the other side of the overgrown debris flow I reached a vertical bank and saw the stream cascading over rocks ten feet below. A major post-fire flood had deposited the hundred-foot-wide debris field, then vegetation had colonized and stabilized it, and finally, winter snowmelt and summer monsoon flows had cut a deep channel along the edge of the debris field.

Of all the backcountry water sources I’ve visited, this had to be the purest – its origin is the back slope of the summit, an endangered-species preserve where humans are prohibited and there are no trails, and the entire canyon has been free of livestock for decades. I just had to fill my drinking bottle and take advantage of it.

Surprisingly, now that I knew what to expect, the bushwhack out of the canyon was easier than I feared. I just had to take it slow.

The descent from the saddle is so steep, it was hard to control my speed going down. I kept telling myself I had plenty of time, then a few minutes later I would find myself running down a stretch of hard-packed dirt. Unsurprisingly, that took its toll on my knees.

But the worst was yet to come. I’d forgotten how much worse the surface is on the final two-mile stretch to the trailhead. This is not only steep, it’s either lined with loose rocks or cut into deep steps by rectangular boulders emplaced by the original trail-builders. The result is one of the hardest trails I’ve ever found on the knee joint.

On the plus side, as I traversed the lower slopes of the tributary canyon I was serenaded by frogs – or toads? – with a resounding croak like a slow, low-pitched machine gun. Due to the long bushwhack, the steep grades, and the brutal trail surfaces, it ended up taking me 8-1/2 hours to go less than 11 miles out-and-back.

I spent the night in my new favorite small-town motel, discovering a burrito that turned out to be big enough for three meals, and waking up to an espresso bar next door. I keep saying I live in paradise, but sometimes it’s hard to end one of these weekend getaways…

April 8, 2024

An East German in the Wilderness

I woke on Sunday not knowing where I would go for today’s hike. I was tired of driving, but snow and runoff were still a problem in the mountains near home. I literally didn’t have any appealing choices, so I started to drive southwest toward Arizona, halfheartedly intending to try another bushwhack in cattle country.

I only made it about twenty miles, then turned back in dismay. I would just bite the bullet and do a less desirable hike nearer home, and since at this point I was getting a late start, it would be shorter than usual.

After a stop at home to review my options on the map, I set out on the highway north, toward the western crest of our high mountains. There I would find a series of options, and since driving helps me think, I would pick one enroute.

I arrived at the trailhead almost two hours later than usual, but with daylight savings time that still left me up to seven hours for hiking. I’d picked the old favorite trail that had first introduced me to our local wilderness. It involves a lot of elevation gain, but I expected deep snow at the top that would make me turn back early without getting much mileage. So be it – at this point I just needed a damn hike.

The sky was clear all around, the air was chilly, but the high was forecast to reach 60 at the mid-elevations.

You’ll notice I didn’t take many photos this time. One reason is that I know this trail so well I could almost hike it blindfolded. The other reason will become evident.

The trail starts at 6,400 feet, climbs over a ridge at 6,800 feet, then traverses down to the canyon bottom, dropping back to 6,400 feet. Then it follows the canyon upstream for a couple of miles, to the base of switchbacks which take another mile to reach the crest at 9,500 feet. The hike I’d done last Sunday, in a storm, had involved worse trail conditions and more mileage and elevation gain, but for some reason this hike felt much harder, especially the steady climb up the canyon bottom. Shortly before I reached the base of the switchbacks, I stopped to dig a lunchtime snack out of my pack, and saw a guy coming up the trail behind me.

I run into other hikers on maybe one out of every five hikes in this region, which is fine with me. One of the great advantages of this region is the high ratio of mountains to people. We simply have a lot more wilderness than we have people who use it, and that enables solitude for those of us who treasure it, and a sense that we’re discovering wild habitat for ourselves.

Sometimes the hikers I meet are even more intent on solitude, and ignore me or toss off a gruff greeting as they pass. Other times they’re friendly and stop for a brief exchange of small talk.

But as soon as this hiker stopped, I could tell he welcomed my company – for whatever reason. He appeared to be in his mid-thirties and spoke with a soft German accent. I asked him how long he’d been in the area, and he said only a couple of days – he was on his way west to Arizona. He immediately announced he was vegan, and complained about the cafe in the town at the base of the mountains, where the smell of frying bacon had nauseated him as soon as he opened the door. He said he was on a goodbye tour of the U.S., returning to Germany after living here for twelve years – most recently on a horse farm in Connecticut. Then he said, “You must know about the BLM and horses?” I nodded yes, and he went on a long lament about his concern for animal welfare and the treatment of wild horses in this country.

He just kept talking, and he seemed like a really nice guy, but I wanted to finish my hike in the time I had left, and said so. I was obviously moving more slowly so he set off ahead of me.

Much later, I reached the patch of deep snow below the crest, and strapped on my gaiters. It was at least 18 inches deep, but fortunately the melting sequence had packed it hard enough that I could mostly walk across the surface. The German’s tracks had veered off-trail at some point so I figured he was bushwhacking to the peak. I avoid the peak because it’s forested and has no view – the trail takes me to a rocky outcrop with a glorious view of all the high peaks of the range.

On the way down, I had just crossed the snowy patch and unstrapped my gaiters when I noticed the German a hundred yards ahead, dropping down through the forest from the peak. I yelled at him and he came up the trail to meet me.

I asked why he was returning to Germany after so long in the U.S., and he struggled to answer. He said he was uncomfortable with the way things are going here, but admitted that politics are bad everywhere. When he’d left Germany there hadn’t even been a Neo-Nazi party, but now they represent twenty percent of the government.

He complained about how bad racism is in the U.S.. He’s been working as a carpenter, and white people in the building trades blame Mexicans for taking their jobs. He also complained about their sexism and antagonism toward sustainable construction. That led to a complaint about materials that are non-recyclable or even toxic, from which he launched on a long, excited discourse about a landfill in Brooklyn that began as a dump for fat rendered from horses before the advent of cars, and is now a park, where relics from past generations keep eroding onto the surface. The German’s complaint there was the “Do Not Remove” signs all over the park – apparently he felt these artifacts should be free for everyone.

He’d been walking ahead of me, which made it harder for me to understand his accent, and he kept wanting to stop and just talk, so finally I passed him and took the lead. I was beginning to resent the nonstop conversation, which completely prevented me from enjoying the wilderness and views around me, and disrupted my usual rhythm of stopping for pictures, snacks, and hydration. Instead, I began hiking faster than usual and made much fewer stops.

Back on the subject of the U.S. vs. Germany, he said he’d grown up in East Germany, where his family had been oppressed by both the Nazis and the Russians, so he sympathizes with Native Americans. But he complained about how rude they’ve been on the few instances he’s met them. That’s when I told him about my place in the desert and my Native friend, and the German said he really envied my experience. He wondered if maybe he was making the wrong decision, and should stay in the U.S., moving to the West where people might be more open-minded.

I mentioned I’d done carpentry myself since childhood, even working on construction projects here and there as an adult. That’s when the German stopped complaining and really lit up. He said his passion is for wood-framed construction, and began an endlessly detailed description of the little houses he built for the goats on the farm in Connecticut. One he built in the shape of a wooden ship, with a surrounding deck, a sleeping loft inside, and a wooden anchor on the front door. He told me about something he’d built out of cherry and walnut – maybe some kind of cabinet – with wooden hinges and a wooden lock. This is when I began to visualize the classic old German craftsman out of Grimm’s fairy tales, deep in the Black Forest, carving gingerbread decorations in the lintels of doors and windows.

More random stories of living on a kibbutz in Israel, persecution by hard core Zionists, wanting to have kids but accepting it wasn’t likely to happen. He enjoys being the “bad uncle” to his sisters’ kids but rejects the loss of freedom that comes with raising a family. He didn’t completely monopolize the conversation – I regularly interrupted with questions and comments, and he did ask me a few questions about my life – but by the time we reached our vehicles I was more than ready for a break.

His vegan and animal welfare complaints had put me off at first, since they often reflect an ignorance of ecology and a bias toward domesticated animals at the expense of wildlife. In general, he’d spent a lot of time sharing simplistic complaints on complex subjects. Then he’d proudly mentioned a photo someone had shared of him taking a dump off the side of a sailboat, and said since he’d left the farm he’d launched a project of him pissing at various scenic spots around the U.S., which he was sharing with friends. I said I expected his friends’ kids would love that, and I finally realized that even in his 30s, the German was a kid at heart – that characterized everything he’d said. And in some way, that made him lonely, and anxious to connect on this wilderness hike.

I’d been able to share my experience of moving west to escape the European worldview that dominates the old colonies of the eastern U.S. I’d described how I’d pursued, met and befriended Native Americans, and how they’re struggling to survive our “progress”. I’d described how I’d moved to southwest New Mexico hoping to grow my own food, stayed on a commune and almost tried to join it. The German and I parted as friends, and we both seemed elated by the experience. He seemed impressed by what little I’d managed to share about my accomplishments and experiences. I can only wonder how he’ll continue to ponder all the topics we discussed, and whether he’ll really return across the ocean to stay – because it sounded to me like he might be better off here.

April 1, 2024

The Winter That Wouldn’t End

I was still trying to rebuild capacity, but most of the high-elevation hikes remained blocked by snow or flooded creeks. I settled on a handful I thought would work, then checked my Dispatches to see when I’d last done those hikes. It’d been a year and a half since I’d done one of my favorites over in Arizona, so I picked that one.

Once again, I underestimated the weather. The forecast for nearby towns predicted cool but not cold, rain in the evening, and windy. I ignored the windy part and the elevation differences.

As I left home, the wind, out of the southwest, turned out to be so bad the interior of the car sounded like a jet engine. My noise-cancelling headphones really paid off.

It’s a two-hour drive, the sky looked stormy, and when I first glimpsed the mountains they were enveloped in a dark cloud.

Even after last week’s experience, I was forgetting about the first mile of the trail, which sees heavy cattle use. The beginning, which winds through a maze of shallow gullies, boulders, and big oaks, was completely trashed by cattle, and there were cattle grazing all over the next segment, which climbs through some granite hills to a narrow gully that carries runoff from the crest.

The temperature at base was probably in the high 40s, and I started out wearing only my sweater. The climbing made me sweaty, but the wind made me chilled, and even after I pulled on my shell jacket my still-sweaty arms were freezing.

The trail past the creek was pocked with the hoofprints of one or more horses, but devoid of human tracks. I’ve always been one of the few people that use this trail, especially from the bottom, and it’s often overgrown and hard to follow in places.

Not long after passing the cattle, I discovered my right thumb was in severe pain that seemed to come from the bone itself. I had no memory of injuring it – it was like a sudden-onset arthritis. I use that hand a lot on a hike, no way around it.

The trail climbs through the foothills until it hits the upper slopes, which require switchbacks and long traverses. Here the wind, and the wind chill, became brutal. My arms were still freezing and I wondered if I should turn back. But as usual I just tried to speed up to generate more body heat.

The horses had destroyed the tread on this part of the trail, dislodging the retaining rocks that the trail builders had laid on the downhill side, resulting in loose, pitted dirt and rocks that were hard to walk on and will erode rapidly. And on the final switchback to a saddle on an outlying ridge, I came upon the severed leg of a recently killed deer. I’d seen a dog track and wondered if the equestrians were hunters?

On the next stretch, the long traverse through dense oak scrub transitioning to mixed conifer forrest, the clouds began to break for a few minutes at a time, and that brief sunlight finally warmed my chilled arms. The wind was as ferocious as ever, but the dense scrub oaks, followed by the big firs, gave me some protection.

Here, the equestrians had ripped branches off trailside bushes and trees – the higher branches they could reach from horseback – which they then dropped on the trail behind them. What were they thinking?

I finally reached the saddle on the crest, finishing a climb of more than 3,000 feet. The wind was bending the trees and roaring like a freight train up here.

The crest part of the trail started out snow-free, but the higher I climbed the deeper it got. Fortunately the beautiful fir forest blocked most of the wind. I managed to climb another three-quarters of a mile and 600 feet higher, reaching a trail junction just below the peak. The snow was up to 8 inches deep there and I could see it would be deeper ahead, requiring gaiters. Knowing there are no good views ahead, I didn’t feel it was worth strapping them on, so I turned back.

This is one of those hikes whose reported distance varies widely depending on your source of info. CalTopo, the mapping platform I use, shows today’s hike at 4.7 miles one-way and 9.4 miles out-and-back, but every other source calls it 5.4 and 10.8 – quite the discrepancy. Based on the time it takes me when I’m in top condition, I’m confident it’s close to 11 miles.

The walk back down the crestline took me in and out of that howling wind. It had to be between 60 and 70 mph up there, yielding a wind chill in the mid-20s, which I was not dressed for. I dug my lined gloves and thermal bottoms out of the pack and stuffed them in the inside pockets of my storm shell, so they’d be warm if I needed them.

As I headed down the switchbacks below the crest sleet began to blow in my face, so I cinched my hood as tight as it would go. I could see rain falling twenty miles across the desert, and a half hour later it was moving down the valley below me, where my vehicle was parked.

I was past the saddle on the outlying ridge, down the long traverses into the foothills, when it began to rain, lightly at first then harder. I had to dig out my rain poncho. Fortunately the lower elevations were much warmer.

At the base of the foothills I rounded a small oak tree and came face to face with a bull. I couldn’t believe it – the third Sunday in a row. I wasn’t even sure I was on the trail anymore, so I backtracked until I realized this had to be it. I simply walked around the bull, and he resumed grazing behind me.

When I reached the vehicle, not only was my thumb on fire, but the palm of that hand was hurting as well, so I took a pain pill. It wasn’t enough – it was aching so bad when I got in bed that night, I had to take a second pill to get to sleep.

March 25, 2024

Crazy or Suicidal?

The high elevations were still blocked by snow, so I remained in search of lower-elevation hikes. Driving back from Arizona last week, I’d again wondered about the interesting-looking but unexplored mountains I was passing. Years ago I’d researched them online and concluded they were surrounded by private land, inaccessible behind ranchers’ locked gates. Also, I was trying to maximize both distance and elevation gain in my Sunday hikes, which could only be achieved in the high mountains protected within national forests. But since then I’d found a couple of trip reports from people who’d actually been able to hike in some of those “unprotected” ranges.

So during the past week, I’d spent some time digging deeper online, and found ways to access nearly all those unexplored mountains, all of which were low enough to be snow-free. I picked the nearest one to experiment with first.

I always check the weather forecast for the entire region the night before, and this time, I concluded there might be a little rain in the higher elevations in early morning. I’ve never been so far off with my expectations!

The temperature was in the mid-30s when I left home at 8 am, but by the time I crossed town sleet was falling, and as soon as I hit the highway south I was in a blizzard of sleet which began piling up on the road. The temperature would continue to drop throughout the day. I pulled over and shifted into high-range 4wd, but whenever I tested for traction I found 45 mph was my safe limit.

These conditions continued through the mountains south of town, and even when I reached the vast valley beyond, dropping from to nearly 4,000 feet elevation, the storm ended but visibility remained limited to about five miles.

My main source of information on these unexplored mountains turned out to be a website for “peakbaggers” – an obsessive and competitive subculture similar to birders, whose goal is to add as many hilltops as possible to their life lists, while mostly ignoring the rocks, habitats, and wildlife they’re passing on the way.

Whereas hikers’ websites focus on developed trails in national parks, forests, and preserves, peakbaggers are used to bushwhacking off-trail, because the vast majority of “baggable” hilltops are not on protected land. They’re accustomed to finding ways around gates and fences, while ostensibly honoring private property.

Like my beloved Mojave Desert, the stateline region near me has few paved roads, and the range I was heading for today is fifteen miles off the highway – you can only see its distant profile, none of the details – and that’s one thing that made it appealing. A sort of final frontier. The drive started with 56 highway miles and ended with 20 miles on dirt ranch roads.

This range belongs to a rare class with only one other member that I know of: long, skinny north-south mountain ranges split in half by an interstate highway. And it’s made rarer still by lying along the state line. The gate I reached at the end of my road, plastered with “No Trespassing” signs, lay right on the border.

I found myself in an interior basin surrounded by low hills and buttes topped by bands of caprock. Directly north loomed the mountain I wanted to explore, a rampart of cliffs deeply dissected by steep canyons. From the road where I parked there was no apparent route up, but the peakbaggers had found a way up the leftmost canyon through narrow gaps in the cliffs.

Their goal is always to reach the peak by the fastest and easiest route, but my goal was to cover as much distance and elevation as possible in a day hike, so I’d planned a route up the rightmost canyon, which I hoped to continue northward from the peak along the crest, maybe even returning by a different route farther west. But without a trail, I had no way of knowing how hard and slow my route would turn out to be. The peakbaggers’ route involved 6 miles out-and-back with 1,800 feet elevation gain, and all 18 of them on record in the past 15 years had followed it slavishly.

Like them, I initially followed the fence north along the state line. The basin had been heavily grazed but I found no recent cowpies on the New Mexico side. On the Arizona side I came in view of an abandoned horse trailer, then a corral and water tank. When I came parallel to it I saw 15 or 20 cattle grazing over there.

I cut northeast toward the mouth of the canyon I wanted, over a broad stony debris field cut by meandering sandy washes – tough and slow walking. I reached another fence and had to crawl under it where it crossed a wash. Eventually I reached an alluvial fan covered with catclaw, mesquite, and prickly pear that rose gently toward a low divide. I was able to follow a wash partway, then at the end, picked my way up a difficult slope lined with sharp volcanic rock and masses of prickly pear.

I’d had my eye open for cattle, and finally saw a herd of a couple dozen off to my right, in an elevated draw beyond the mouth of the canyon. Based on the fencing I’d seen, they could drift across my return path, but I couldn’t tell if there was a bull among them.

Weather had been moving around the landscape all morning. I’d been hiking across open country and wasn’t worried about finding my way back until I reached the steep canyon. Working my way up the first wash I came to, I had to divert up the opposite slope to bypass boulders and big oaks, and discovered the canyon bottom was divided into two parallel washes by a tall debris pile running down the center. The washes were choked with boulders and vegetation, and the debris pile consisted of jumbled boulders that were really slow going.

The drainage was blocked ahead by a cliff, and above that loomed the caprock with its narrow gap. At left I could see a steep slope that I hoped to use as a route to the upper gap. I began memorizing features of the landscape I could use to find my way back.

Experts advise “seniors” to work puzzles as a way of exercising and retaining their memory skills as they age. Bushwhacking is one way I do that. On a hike like this, I stop at critical points and look both forwards and backwards, trying to memorize features for my return, and I do that at least a dozen times per hike. Features I’ve only seen once, in a landscape I’m seeing for the first time. If I had GPS or a smart phone I suppose I could record my route, but this is a much healthier way.

The slope I’d scouted turned out to consist of loose rock lined with agave and prickly pear, dissected by narrow, deep gullies – one of the most hazardous hikes I’ve ever done. And shortly after I reached it, dark clouds closed in and sleet began to fall. I was now crossing the state line into Arizona.

By the time I reached the little saddle in the gap at the top, I was in a full-on sleet storm. I huddled in the lee of a boulder to check the topo map I’d printed at home. I knew I had to circle behind the cliffs to reach the summit, and based on the topo map I’d expected some sort of traversible slope, but all I could see from here was boulders and thickets.

I wasn’t happy about it, but I fought my way up through storm, thickets, and boulders, eventually emerging on a more open slope where I could see more sheer caprock above. I had to keep traversing and gaining elevation while staying below that.

I was on the back side of the mountain now, although the storm still obscured the view below me. At the end of the caprock I rounded a bend and overlooked a shallow cove, the head of a backside canyon. The slope was mostly bare of vegetation and boulders, and as I made my way across it the storm intensified. As I approached the saddle at the top of it, the wind howled through, hammering me with sleet. What the hell was I doing here? I’d had no inkling the weather could get this bad.

It was so bad I was in denial. I just wanted to keep going until it either stopped or I reached some kind of shelter. And as I began traversing the opposite slope, the storm suddenly subsided, a patch of blue sky opened, and a view of the northern plain emerged, 2,000 feet below me. I’d been climbing for the last two hours without a drink of water, and it was lunchtime, so I stopped in the temporary sunlight for a drink and a snack.

Due to Raynaud’s syndrome my fingers had gotten chilled in the lightweight glove liners I’d started out with, and I now switched to the lined Goretex gloves. I had to keep flexing them for the next half hour or so to get my fingers warmed up, and after stashing the glove liners in my pocket to warm them up, I would wear both pairs, one inside the other. When the sun wasn’t shining it was damn cold up there!

With storms drifting over the crest, I found the topo map inadequate to orient me. I had no idea how much farther the peak was, or what kind of terrain to expect. The way ahead threatened to be blocked by cliffs or boulders, but I picked my way across it, rounding another corner, where I was relieved to find a gravel-lined rock ledge. I was able to follow this a hundred yards or so, until it ended in a maze of trees, brush, and boulders that choked a steep, narrow defile. In the distance beyond loomed a hunchbacked peak – much too far to be the summit I sought.

I started clambering up through the maze, hoping the summit lay somewhere above me. Another storm was forming. A tiny voice kept saying I should turn back before I got in real trouble, but I seemed to be on autopilot. I literally threw myself into thickets of stiff brush, clambering over them on all fours like some kind of giant beetle. Finally I emerged into the head of the narrow gorge, and thought I saw a way up it to the crest. It turned out to be a rockfall just wide enough for me to climb up, and at its top I emerged onto a gentle slope across the top of which ran a fence.

It was a very recent fence, and as I approached it I saw it crossed a rock pile where I could probably step over it. The wind was howling through here, too, but mercifully carrying no sleet. Once past the fence, I saw the peak rising at my left. It was a steep climb in wind that constantly threatened to topple me on the rocks, but I’d come this far and wouldn’t be stopped. At my right was the edge of the caprock and a dropoff of nearly two thousand feet, but I didn’t even glance at the view until I’d actually reached the top.

The view was spectacular, but what next? I’d originally hoped to continue northwest along the crest, but it’d taken me more than half the day to get here, and it was time to turn back.

Amazingly, all that memorizing paid off – I was able to follow more or less the same route going down as coming up. As usual, I kept surprising myself by encountering features I remembered from the morning.

But the weather had prevented me from hydrating sufficiently on the way up, and that took its toll on the way down – I developed a bad cramp in my left thigh just as I was picking my way across some gnarly rocks between two prickly pear. Perching precariously in place, I somehow managed to take off my pack and mix some electrolyte supplement in my water bottle, and after ten minutes of tense drinking and resting was able to proceed.

When I reached the gap at the head of the first canyon, recalling all that loose rock and sharp vegetation below, I realized it’s very similar to a perilous descent in my desert mountains, which I’d last revisited in fall of 2022. Every time I do something like this, I wonder how much longer I’ll be able to safely subject my aging body to such abuse and danger. I ended up falling three times on this hike, but each time I landed softly and safely.

I did stab my finger on an agave blade on the way down, and was surprised not to impale myself many times. I’ve never hiked in a place so full of blades and spines.

The cattle had moved off by the time I reached the mouth of the canyon, but as I picked my way down the difficult slope of volcanic rock and prickly pear, I noticed them a half mile away at the base of the alluvial fan, near my route back. To avoid them, I would divert westward across the difficult debris field, toward the state line.

But they noticed me, formed into single file, and began running west to intercept me. As I continued, they stopped and began to mill around in the area where the fences converged. I noticed a bull in their midst, and he stopped and turned around to see what I would do. I had to divert eastward again to avoid aggravating him.

About halfway down the basin toward my vehicle, I noticed an unusual animal off to my right. At first I thought it was a goat, but then realized it was a big black dog with white markings. It saw me and began barking. Great!

I kept going, but the dog kept barking, and another bark joined it, behind me. I ignored them, but their barks kept getting closer. Dogs don’t generally scare me, but here I was alone in the midst of someone’s very remote cattle range, and I had no idea what to expect. I kept going, the barks kept getting closer, and finally I turned to confront the two dogs. They were really worked up, angrily jumping up and down about a dozen feet away across a shallow wash. I talked to them in a friendly voice, calling them good boys, but they wouldn’t calm down.

Finally I just turned around and kept going, picking up a hefty branch along the way, and eventually they lost interest and turned back.

Thus ended my big experiment with off-trail hiking in unprotected ranges. A 71-year-old man, hiking alone far off the beaten path, overtaken on a mountaintop by winter storm and gale-force winds, falling on loose rock surrounded by lethal blades and spines, threatened by bull and dogs. Many people would hesitate to believe my story, and most people would consider me crazy or suicidal.

I was plenty sore, and the cramp returned as I drove out, trying to work the clutch pedal over rocky stretches of road. I had to stop, get out, drink more water, and stagger around for another ten minutes until it began to fade. But I managed to get home before dark – just as another unpredicted sleet storm began.

March 18, 2024

Sunlight and Shadow

For me, the onset of daylight savings time, in March of each year, means that I can venture farther west for my Sunday hikes – because Arizona rejects daylight savings time, and when crossing the state line, I gain an hour. This is especially important in late winter when the high mountains are still covered with snow, because Arizona offers more lower-elevation hikes, and with daylight savings time, I can leave my home at 8 am as usual, drive 2-1/2 hours, and still hit the ground at the reasonable time of 9:30. Yeah, I’m still not gaining much daylight – but everything’s psychological.

I decided to return to the area with interesting granitic and metamorphic rocks and dramatic topography that I’d started exploring a little over a month ago. It can also be accessed via an old ranch road that would allow me to bypass the initial steep climb and deep canyon and get closer to my original destination, the ridge above the next watershed to the north.

I’d already discovered in a short midweek hike that I’d lost a lot of conditioning during my recent trip back east. Today’s hike would require a climb of over 3,000 feet, but the round trip wouldn’t be much over 8 miles, so I should have plenty of time to stop and catch my breath.

The dirt road to the trailhead is less than 4 miles long, but it took 20 minutes to drive because much of it is rocky. It crosses the mouth of the creek that drains the deep canyon I’d hiked to last time, in a grove of cottonwoods that had just leafed out. Then it climbs past a corral to a bench above the creek, where the trail begins.

There was already a cloud mass hanging over the crest of the range, and as the day progressed, the entire sky filled with scattered, ever-changing cumulus clouds, so that I found myself moving between sunlight and shadow, warmth and chill. Sometimes it became quite dark.

The trail was steep from the beginning. The overall average grade is almost 14%, making it one of the steepest long trails around, with a lot of short climbs in the 30% – 40% range. I soon came to a gate past which the vegetation changed dramatically, and I understood why the broad slopes above are blanketed with stands of tall native grasses – cattle have been fenced out of this entire watershed.

I spent a long time climbing over the rounded foot of an outlying ridge, finally reaching a side canyon that I knew led to the junction with the trail I’d explored last month. Past there, I expected to have to find my own way up the abandoned, overgrown continuation. But the rocks here continued to excite me – so much like the rocks in my desert mountains.

I reached the junction, and had gone a few yards down the main trail when I suddenly realized it had been cleared, and very recently – within the past couple of weeks. I’d actually been looking forward to some routefinding and bushwhacking, but this meant I could go faster and potentially farther.

The trail leads up the gentler left slope of a canyon whose right slope is lined with granite, and a sheer-sided granite outcrop above that slope became my landmark. Below that outcrop, the trail cut sharply left into a smaller side canyon, and the vegetation changed dramatically.

Whereas below, the slopes had been lined with grass and open oak woodland, from here on up they became a steep maze of boulders and thickets of oak, manzanita, and thorny locust.

I was aiming for a saddle on the ridge above, but the convoluted terrain at the head of this watershed required the trail to switch back and forth before getting there. And the grade was still steep so I had to stop often to catch my breath. It had rained here yesterday, and the ground was damp, but thankfully in this granite terrain the trail was sandy, not muddy.

Finally I could see the high saddle up ahead and knew I was on the verge of a new watershed and a new canyon.

Normally in an out-and-back hike, after only going 4 miles I would be only about halfway to my destination. But I’d dreamed about reaching this point for a long time, and I wasn’t in shape to go much farther. Still, I continued down the trail a few hundred yards – the trail crew had continued too – hoping to get a better view. The slope I found myself on had been burned in an old wildfire, but still bore some living pines and firs, whereas the opposite slope, far across the big canyon, was heavily forested.

I now had a phone signal from the city below the mouth of the canyon, and by the time I’d returned a call, I decided to call it a day. I discovered later on the map that if I’d continued only about a half mile, I would’ve rounded a corner and obtained a view of the summit of the range.

Still, I felt great. After going three weeks without a hike, I’d climbed over 3,000 feet and gained a view into a new watershed. And this is still my favorite place for rocks in our entire region.

On the way down, I noticed isolated, charred skeletons of pines rising among the oak thickets on the upper slopes. These slopes which I’d accepted as covered with thickets had once been lined with mixed-conifer forest.

Passing some burned snags cut by the recent trail crew, I caught a strong odor that immediately sent me back to my childhood bedroom with its cedar chest. I leaned to sniff the fresh cut. Years after the wildfire that had killed the juniper, the heartwood retained enough fragrance to fill the air around it.

Past the trail junction, paying more attention to my surroundings, I discovered a few more early flowers. The grassy slopes enabled clear views, and far below me I watched a white-tailed buck crossing between clumps of oak. And when I finally reached the livestock fence with its hikers’ gate, what did I see on the other side but a bull, blocking the trail!

With the fence between us, I yelled at it to move, with no effect. I was in no mood to wait, so I passed through the gate, but on the other side I caught my sleeve on a prickly pear cactus. Standing about twenty feet away, the bull watched me, unconcerned, as I cursed and struggled out of my sweater. By the time I’d picked the tiny glochids out of my elbow, I was more pissed at myself than worried about the bull. It was a young one anyway, and hornless, and it had resumed grazing, ignoring me. I’m still getting used to these local bulls – so far they’ve seemed to lack the aggression of our desert bulls.

I made a short detour around the young bull and reached my vehicle with plenty of daylight left.

The entire crest was obscured by clouds when I left for home the next morning, and a storm brewed to the east as well. That country is littered with low desert ranges that might offer some interesting winter hikes.

February 19, 2024

Twelve Years After

The trail up the main canyon on the west side of our high mountains, the canyon that drains the highest peaks of the range, has been catastrophically washed out and inaccessible since the mega-wildfire turned the upper slopes into a moonscape twelve years ago.

While looking for another snow-free low-elevation hike for this Sunday, I thought of one that leads to that abandoned trail. So I checked the trail maintenance log, and to my surprise, discovered that the canyon trail was cleared last fall, to 3-1/2 miles beyond the junction. Even better, a trail up a major side canyon was cleared to about the same distance. Long-abandoned trails in the heart of the wilderness are opening up – at least until the next wildfire or erosion event.

The frost on the windshield was fairly light when I started on Sunday morning. The sky was mostly clear and the high in town was forecast to reach 60. It takes an hour and fifteen minutes to reach the trailhead, perched on a spectacular mesa high above the mouth of the canyon.

I’ve only hiked the trail into the canyon twice in seventeen years – it’s too short and involves too little elevation gain to make the drive worthwhile for a day hike. But it’s a popular trail so I was surprised to find the trailhead parking empty.

When I surmounted the first outlying ridge and could see up-canyon, I realized this two-mile trail into the canyon is actually a spectacular hike in itself – because this is one of the most dramatic canyons in the range, lined with cliffs and studded with monumental, colorful rock outcrops.

Halfway between the trailhead and the canyon bottom, the trail swerves back into a deep side canyon. I was to learn that with all the snow we’ve received, every side canyon now hosts a running stream.

Climbing back out of the side canyon, you find yourself traversing the north slope of the main canyon below isolated outcrops, with the creek roaring far below. Across the canyon on your right loom nearly sheer cliffs. Eventually you encounter switchbacks that take you down toward the creek.

I’d expected the creek to be in flood, and I wasn’t wrong. The newly cleared trail up the side canyon is a little over a mile beyond the junction, past a big washout that had stopped me in the past. Sure enough, last fall’s trail crew had cleared a path across the washout, but when I reached the mouth of the side canyon, about thirty feet of icy, foot-deep water separated me from the opposite trail. I would have to continue up the main canyon.

Now I was in view of the rock towers on the high ridge between the two canyons. And in a third of a mile I expected to reach another trail that comes down the north slope at my left. The upper part of that trail is an abandoned mine road that had long been washed out and buried in debris – I’d descended it two or three times shortly after moving here, to reach a swimming hole in the creek. But now, when I reached the biggest washout, I discovered someone had recently brought a Caterpillar down the road, clearing it and filling the washout in the trail.

Past that road, the trail climbs higher and higher above the creek, meeting the wilderness boundary after another third of a mile. Now the canyon was beyond spectacular – but clouds were darkening the sky overhead. I began noticing how much work had once been put into building this trail, across talus slopes, rock faces, and slopes of loose dirt. I’d never seen a trail anywhere in this region that had been built like this – with dry-stone retaining walls up to fifteen feet tall supporting terraces up to 80 feet long, and walkways across gullies reinforced with one-inch rebar and heavy wire mesh. By contrast, our recent trail crew had only been able to clear a temporary path that would wash out at dozens of gullies in the next heavy rain.

Eventually, the trail began dropping toward the canyon bottom.

In the canyon bottom, I found some recent deadfall blocking the trail – the first I’d encountered today. Here, at about 6,200 feet elevation, shade had kept snow from melting, and I found the very recent tracks of two hikers and a dog. They ended at the first creek crossing in the entire distance of this trail so far – where I would have to stop as well. The trail crew had stopped here, but the old, abandoned trail continues for another ten miles, climbing to the 10,000 foot crest just below the highest peak in the range. From the highest parts of the trail, I could just glimpse that crest, its deforested, snow-blanketed slopes glittering in occasional sunlight.

The clouds gradually broke up as I headed back, and sunlight brightened the colors of lichen on the outcrops above me.

Past the flooded junction with the side canyon trail, the trail enters the shade of the canyon’s nearly sheer south wall. And I began noticing how big the sycamores grow here along one of the range’s few perennial streams.

Reaching the junction with the trail out of the canyon, even after climbing the switchbacks I was still mostly in shade from the south wall. But when I reached the deep side canyon with its spectacular rock bluffs, I finally found myself on a west-facing slope, catching some warming rays from the setting sun.

Past the side canyon, I was in the home stretch, and once I’d climbed the opposite side I was back in the last of the sunlight. It’d taken me almost 8 hours to go less than twelve miles, but I’d gone slowly, stopping often to admire the view and take pictures, and that newly cleared trail had involved a lot of careful scrambling. I’m looking forward to returning when the creek’s low to explore that side canyon trail!

February 12, 2024

Danger and Discovery

Even before Saturday, all the high elevation trails had been blocked by deep snow. But on Saturday it snowed lightly on and off for about 16 hours, leaving up to four inches here in town, at 6,000 feet. Yet daily highs were ranging from the 40s to the 50s throughout the region, meaning creeks would be flooded with runoff and most low-elevation trails would be muddy.

Before going to bed Saturday night, I finally decided to explore a mountainous area over on the Arizona border that I’d been eyeing from a distance for years. It ranges from 4,000 to a little below 7,000 feet, but it features dramatic rocky peaks, with no hiking trails but a network of old mining and ranching roads. It’s more than an hour and a half drive to get there, and it would be a shot in the dark – I didn’t know what kind of surface to expect, and the roads and the ground might be too muddy now.

The only info I could find online was a trip report on Peakbagger from a guy who tried to climb two of the most dramatic peaks. He failed, but dropped his phone near the top of one peak and had to return the next day to retrieve it. His report mainly consists of complaining about the lost phone, but it includes a GPS route from the nearest road that might be useful.

But getting out of town turned out to be the biggest challenge of the day. Both driver- and passenger-side door locks were frozen, and the de-icer I’d bought earlier didn’t work. I had to climb through from the rear hatch to start the engine and the heater, and it took 35 minutes to warm up the interior enough to free the locks and melt the frost off the windows.

I anticipated ice on the highway, and sure enough, immediately outside of town the surface turned to pure ice. I switched into high-range 4wd, but was still limited to 35 mph – at that speed I could feel my all-terrain tires begin to slip. Big pickups and tractor-trailer rigs passed me going 45 – I guess the extra weight and tire surface helps. The ice lasted half the distance south through the low mountains, and it was a tense drive.

By the time I left the mountains for the vast alluvial plain, dropping below 6,000 feet, I was running so late I knew this would be more of a road trip than a hike. But as I drove north toward the new country, the rocky peaks emerged from the horizon, tantalizing me.

The dirt road that led to them was the first surprise. The first part of it leads north up a rough wash and clearly floods and washes out after a heavy monsoon rain. It’s only after the first couple of miles that the road climbs out of the wash and spends the rest of its time up on ridges, on surfaces that range from gravel to packed dirt. This is lonely country; I was the only driver on this road, all day.

My second surprise came when I checked the map again and discovered this area lies within my county. The longest route across the county I grew up in in Indiana takes less than a half hour; that this remote area is an hour and a half from my hometown, which is in the middle of the county, is pretty crazy.

Approaching the first peak, the road reached the edge of a bluff with a dramatic view. To take the peakbagger’s route I would continue on the road until it reaches the foot of the peak. But below me was some country that looked interesting in itself, and would yield more mileage and elevation in my hike. There was a high-clearance 4wd road leading down into this country – it turned out to be very sketchy, but by stopping regularly and scouting lines I managed to make it all the way down to a corral, windmill, and stock tank on the bank of the big wash. Cattle were milling about there, so I drove back up and parked on a ledge.

I had an amazing vista: it appeared that I could follow the wash upstream, through a dramatic gap in low bluffs, and from there, up alluvial slopes to the foot of the cliffs. My map showed that the hidden north side is gentler; I hoped to circle around and climb it from the back.

It had been a long time since I’d bushwhacked off-trail, but I was motivated by having new country to explore. The main obstacle seemed to be waist-high thorny mesquite, which blankets heavily grazed land throughout the Southwest. I would just have to wind my way through it.

This is very dry country. I could see snow on northwest slopes down to about 5,400 feet, but I was surprised to meet running water in the wash – bedrock was close to the surface, and when it emerged, there were interesting water-sculpted features and cascades.

The gap in the rock bluffs turned out to be a slot canyon that involved some creative scrambling. I’d forgotten how much fun hiking without a trail can be!

Past the bluffs I emerged in a sort of overgrazed bajada, a rocky expanse of cactus, grass and mesquite that was at first like a superhighway leading toward the base of the peaks. Farther up, it was divided into ridges and gullies so I had to pick a route, but I came upon a well-marked cattle trail that led me up to an old fence and gate that divided this from the grazing on the north side of the peaks. The gate clearly hadn’t been opened for years and took all my strength to re-close.

Now I was nearing the saddle between the two peaks, and needed to start traversing up the slope of the right-hand peak. I didn’t know what I would find on the north side and I wanted to start gaining some elevation while I could. It was a 20-degree slope, and I began encountering snow, but had thankfully left the mesquite behind.

I was intrigued by a narrow gap in the cliffs above, a slot that appeared to contain a steep chute that might be a shortcut to the crest. But I could see snow in there, and I had no idea how technical it would get up close, so I filed it away and kept traversing.

As I rounded the corner toward the north side, I could see a towering fin of reddish rock blocking my way ahead. Between me and the fin lay a steep snow-covered slope heavily forested with pinyon pine – this would be my only route to the crest. The grade was more than 30 percent, and the trees appeared to get thicker toward the top.

That forest lay mostly in the shade, so I didn’t mind the effort of climbing – it kept me warm! But the ground beneath the 4-inch-deep snow consisted of loose gravel or scree so there was a lot of slipping. The steep grade required me to sidestep most of the way, zigzagging between trees.

The slope narrowed as I climbed, with a cliff closing in on my right and outcrops emerging on my left. The cliff on the right eventually forced me to cross the outcrops on the left, where I found myself on an even steeper east slope strewn with deadfall, scrub, and bare scree.

After finding my way across that final slope, I emerged on the north end of the crest. I’d never actually believed I would make it up there, especially while climbing that forest slope, so I was inclined to just savor the moment and call it a day.

But after checking my watch and calculating how much time I had left – assuming the ice would’ve either melted or been cleared off the highway home – I realized there was no reason why I couldn’t continue and try to reach the peak, which loomed another 200 feet above the ridge south of me.

First I had to climb another steep, forested, snow-blanketed slope. But when I did, I found myself standing on the rim of a great stone funnel, facing the slot in the cliff I’d wondered about from below. Vertical cliff walls towered on both sides of the slot, and when I shouted, it came echoing back. A chute of scree fell vertiginously away below me. It appeared that you might be able to climb it from below, but going down would be terrifying and probably suicidal.

I’d been excited to reach the lower edge of the crest, but now I was ecstatic. This was the most spectacular rock formation I’d ever reached in all my years in this region.

And the peak appeared to be only a short climb above.

I kept climbing up a slope of bare rock with a thin coating of snow, and reached a wall of stone, with the summit looming behind it. The only gap lay at my right, a window at head height, its sill a 45-degree ramp cascading to a drop of hundreds of feet, with no hand or footholds I could see.

I took off my pack and tried edging toward the window. But I soon ran out of holds. If I was roped and anchored, with a partner, I probably would’ve tried it. But gripping the last available hold, I reached my camera up over the sill, and it didn’t look like there was a non-technical route to the summit on the other side.

I estimated I’d gone between three and four miles in 3-1/2 hours – about what you’d expect while routefinding and bushwhacking new terrain. The alluvial slopes had gone quickly, but the slot canyon and snow-covered upper slopes had gone very slow. I expected the descent to be treacherous.

But the descent of that snow-covered scree actually turned out to be both easy and fun – probably because there were plenty of trees and branches so I wasn’t worried about falling. And my landscape memory served me well on the lower ground – I only strayed once, finding myself across a deep gully from the cattle trail, but that was easily remedied.

I reached the stream and the slot canyon sooner than expected, and not long after, the windmill appeared above the trees of the big wash. Back at the vehicle, I suddenly realized the shrubs surrounding me were creosote bush! My favorite desert plant, after a day of the kind of hiking I treasure in the desert. And I was left with plenty of time to get home before dark.

I’d only gone 6-1/2 miles and climbed a little over 1,600 feet – I would normally consider that a failed day trip. But how can I forget standing on the crest of that great stone rampart, overlooking a hundred miles of wild country – and a little farther down the crest, in that echoing amphitheater of stone with its narrow gateway over the same country, its perilous cascade of scree falling away at my feet. Fortunately, there’s more to explore in that area.

I encountered a final mystery on the way out – where the road runs down the wash, the bank was lined with half-buried old cars. I couldn’t tell whether it was by design or by accident – some trailer-trash rancher upstream might’ve had a junkyard that was washed down in a flood?

February 5, 2024

Round the Mountain

Today’s mission involved a trail I’d been wanting to try for more than a year. It traverses the east slope of one of my favorite ranges across the border in Arizona, at mid-elevations so that I expected it to be snow-free in winter. It begins in the big southeastern canyon at just over 6,000 feet and tops out on the northern crest at 8,700 feet, but in crossing a half dozen intervening ridges and canyons, it climbs up and down as much as a thousand feet per canyon, so an out-and-back hike can accumulate some decent total elevation gain.

The full one-way distance is more than fifteen miles; I was hoping to get about halfway and back in a day hike. But the drive is a little over two hours and I couldn’t avoid getting a late start – it took me fifteen minutes to get the hard frost off my windshield at home.

I drove west under a cloudy sky, but it was beginning to clear as I drove up the canyon to the trailhead.

The southeastern trailhead is on the highway up the canyon, but the map showed that I could avoid the first intervening ridge and thus get farther into the backcountry by taking a short cut from a lower picnic area. I found an older man parked there in a pickup with camper shell; he preceded me up the trail dressed in colorful old-school flannel – making me feel like a real yuppie in my high-tech fleece. I soon passed him, and he remarked on how cold it was.

But this first segment of trail, climbing to the first ridgetop, unfolded at an average 15 percent grade, so I quickly shed layers. Sunlight glinted off the snowy crest thousands of feet above, while the thawing dirt of the trail had been deeply chewed up by horses as well as hikers’ boots. Thankfully it was sand and gravel and didn’t stick to my boots like the clay mud farther north. And I was admiring the surrounding igneous boulders and outcrops, which reminded me of my beloved desert.

That first climb was about 1,300 feet, and ended at a knife-edge saddle overlooking a completely new watershed. The tallest peaks of the range glittered above, and I could hear a creek roaring a thousand feet below. Far to the north I could see a prominent bare-rock peak rising from the distant ridge I hoped to reach. From here, it looked much too far – especially since at the end of the day I’d have to climb back up out of this canyon.

The upper part of the descending trail was frozen solid under a thin layer of snow, and was steep enough that I had to go slow to keep from slipping. This trail was literally clinging to the wall of the canyon, with overhangs in some spots. Eventually I reached switchbacks that were mostly in sun, but there were so many I soon lost count. It seemed to take forever to reach the creek.

Brush had been cut recently all along this trail, and cut branches had often been left blocking the trail. The canyon was impressively rocky; the bottom was lined with sycamores; I easily found stepping stones to cross on.

Although the slopes on the opposite side of the canyon were gentler, they were also rockier, with big exposed slabs of igneous rock. After crossing a much smaller side canyon, I reached a bigger side canyon bearing a creek as big as the first, lined with solid rock. I began noticing metasedimentary rock with deformed strata just like the rock on my desert land. This is what I love – much rockier than the landscape around my New Mexico home.

Past that canyon, the trail climbed over a low divide where I reached a junction with an ascending ridge trail, now abandoned, then down into a hollow where I met the lower end of the abandoned trail. The recent trail work ended here.

Past that junction, all human tracks ended and the trail was either blocked by shrubs or overgrown with tall grasses. But I was able to keep going by reading the landscape.

I made it another two-thirds of a mile before running out of time. My planned destination was another mile and a half farther and 1,200 feet higher. With an earlier start, I might’ve made it.

But I wasn’t disappointed; this route had turned out even better than expected. Sure, it’s a challenge climbing over those intervening ridges, but this turned out to be the most spectacular landscape in our region, and I look forward to returning in better shape, and with more time.

I flushed a white-tailed buck out of the second canyon, and a dove out of the brush along the trail, but I was surprised not to see any hawks or eagles.

I took my time climbing out of that first deep canyon. It did take about an hour, but the frozen part was easier going up than going down.

The final descent to the trailhead was mostly in shade. I discovered someone had come partway up on horseback while I was over in the backcountry, so the trail was even more chewed up than in the morning.

Another night in a motel, followed by a lonely drive home through a wild landscape.

January 29, 2024

Reset and Recovery

I assume everyone has experienced setbacks, and starting over. Losing the ability to do something essential, and facing a slow, arduous recovery of that ability. That seems to be the theme of my life now – every few months, I lose the ability to hike, and I have to fight my way back to a slightly lower capacity than I had before – so that in the long run, I’m gradually losing capacity. One step forward, two steps back.

When I say essential, I mean hiking is the way I keep my blood pressure low. When I can’t hike at capacity, my blood pressure quickly goes up 30 points, and if it stays there indefinitely I’ll have to start taking daily meds like most people my age.

Today was supposed to be my latest recovery hike, after more than a month off. I knew I shouldn’t tackle a hard one, and my favorite crest hikes were inaccessible anyway because we had more snow last week. I finally decided on a canyon hike I hadn’t done since last May. It’s a slow climb through a flood-damaged canyon to a mid-elevation saddle, and from there I could descend into a second canyon if I had time and the inclination.

It was a little below freezing when I left town, but it was forecast to reach the mid-50s later. Approaching the mountains on the highway, I saw a lot of snow above 8,000 feet – my saddle would be at 8,200, which shouldn’t be too bad.

This is a trail I’ve hiked many times, but it was washed out a few years ago. Last May I discovered that the first two miles had recently been cleared, and beyond that, it was slow going but I could find my way.

This time around, I expected to be out of shape from the hiatus, and at 6,800 feet, beyond the cleared section, I was surprised to run into some snow, which made it even harder to get through the obstacles. Boulder-choked narrows that had to be climbed around, debris flows of loose rock, big snow-covered logs that had to be crawled under or cleared of snow and climbed over. And that was only in the canyon-bottom section.

A mile beyond the cleared section, I came upon three heavy-duty cardboard boxes with plastic handles, containing square seven-gallon water jugs, sitting right on the trail. These could only have been carried in by pack horses or mules, and had to have been left by the equestrian group that has the permit to do trail work. They had to have been left here since my May visit, but there was no corresponding evidence of additional trail work. This was the second time I’ve come upon gear left by these people – using public trails as long-term storage for their gear. The cardboard will rot – what were they thinking?

Three miles in, the trail leaves the creek and begins traversing in and out of side drainages, climbing, at a steep grade, almost a thousand feet to the saddle through dense oak scrub. Since this trail is seldom used by anyone other than me, the stiff scrub has closed over it, and fire-killed trees continue to fall onto it. Since last May, despite a poor summer growing season, I found it had become almost impassable. As a recovery hike, it was brutal, and I had to put on my gaiters halfway up to keep snow out of my boots.

In May it had taken three hours to go the four miles – today, with the snow and worse trail conditions, it took three-and-a-half. I’d really wanted to continue into the second canyon, but only about 50 yards down the side trail I sank into 16 inches of snow and gave up.

In the little saddle, my boots in the snow, I sat in the sun on the end of the only snow-free log, eating my lunch of nuts and jerky, and noticed the last storm had dropped about four fresh inches here, on top of the earlier snowpack. Despite the effort of getting here and my disappointment at having to turn back, the landscape was beautiful and I’d have a fantastic view going down.

The steep grade and tricky footing quickly took their toll on my knees, making the descent almost as slow as the climb, and painful. Remind me to avoid this one in the future, unless I can somehow rebuild my capacity without another setback!