Max Carmichael's Blog, page 4

May 12, 2025

Crossing the T

Again, I was yearning for a long drive to a hike I’d never done before. The region that regularly draws me is the extremely rugged maze of interlinked mountain ranges about two hours’ drive north of here. It’s mostly unprotected cattle range, mostly unknown to hikers, anchored by the tiny town notorious as headquarters of the right-wing anti-government movement. I’ve done enough hikes there to know that most of them are really hard to drive to, and many are overrun with cattle or defended by rogue bulls. But I love the remoteness, the solitude, and the fact that despite being grazed, this area features native habitat in better condition than much of our big, famous wilderness area.

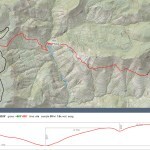

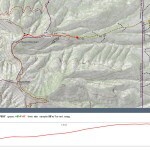

In the upper part of this area, right below the east-west crest that tops out at 9,000 feet, there’s a T-shaped convergence of abandoned, unmaintained, unpublished trails. Back in 2021, I’d hiked the stem of the T from the south – probably the hardest route-finding challenge I’ve ever faced, since there was literally nothing left in the entire seven miles but occasional cairns, many buried in tall grass.

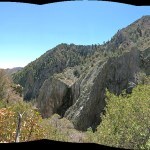

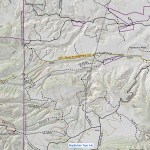

The top bar of the T is divided into an east half and a west half, traversing the slopes below the crest for a total of seven and a half miles. Last fall when my knee injury prevented me from hiking, I drove to the unmarked trailhead at the east end of that crossbar, hoping I could return later to do the whole traverse. But the backcountry access road was so slow as to make it impractical.

So for this Sunday I had a brainstorm. I’d driven the crest road several times, passing the western trailhead of the T’s crossbar at a high saddle in dense mixed-conifer forest. Despite being shown on maps as abandoned, the trailhead features a maintained kiosk. The hike would start with a major descent into a canyon, which I’m usually not crazy about, but returning with an ascent would be better for my knee.

The day was forecast to be warm, but this trail would lie between 7,000 and 8,000 feet, and I believed most of it would be forested with at least partial shade.

At the kiosk, I noticed that someone had tucked a handwritten message into the bottom of the signboard: “You are in the Greatest & Most Blessed Country. Please Learn English. Thank you” I pulled the message off, turned it over, and discovered they’d removed and written on the back of the Spanish-language “WELCOME TO YOUR NATIONAL FORESTS” placard which the United States Forest Service posts on every kiosk.

I found this stranger’s act exemplary and instructive on many levels.

First, you may disagree, but the handwriting and the word “blessed” suggest to me that the writer is a woman. Next, the use of adjectives “greatest” and “blessed” suggest that the writer is insecure about her “country” – she feels her country needs to be defended, while vandalizing a kiosk that is both the creation of that country’s government, and a public resource to be shared among all citizens. This is both ironic and suggestive of dissonance between her idea of “country” and the actual country as defined by its government. To the extent we believe we’re citizens of this country, we all share that dissonance – we want our country to consist only of what we like about it, and we reject anything we don’t like.

In fact, there’s no such thing as “my country, our country, my nation, our nation”. The very concept is a divisive fantasy that means something different to everyone. Borders on a map, armies, a constitution, a capital, a president, an administration, a congress, states, superhighways, power grids, a national currency, etc. etc. – I would argue that all of these defining features are inherently destructive and unsustainable.

The messenger’s use of the word “blessed” could be interpreted in two ways: as blessed by the grace of the Christian God, or in the secular sense of blessed with beauty, diversity, solitude, etc. Again, I’ll make an assumption that she intended the Christian interpretation.

The physical context of this message is also highly suggestive, and may indicate her emotional state. Deep in the forested mountains, surrounded by natural beauty, this woman should have reached a state of serenity, but the sight of the placard in Spanish triggered her insecurities to a laser focus on her language, which she clearly feels is under attack. Despite the use of “please” and “thank you”, her act of vandalism was clearly the result of hostility, triggered by the Spanish language in this beautiful, peaceful location. This is the kind of soul sickness spread by this divisive colonial culture, society, and nation.

If I could reply to her message, I would point out that I’m a white person with an English last name, raised to speak English. But most of my ancestors were Gaelic-speaking Scots who were forced by the English to leave their homes and emigrate to this land, which had been conquered and stolen by the English from Native Americans. English is neither my native tongue nor the native language of this “country”. Like me, the kiosk vandal is a colonist, a descendant of either invaders or exiles. None of us has the right to impose one language or another on our neighbors.

So as best I could, I restored the Spanish placard to its place on the kiosk, and cheerfully set out down the trail.

As I said above, this trail starts by descending into a canyon – over 700 vertical feet – and unfortunately for my knee, the grade averaged more than 20 percent and increased in places to over 40 percent on loose rock or scree. Of course, I found none of the elaborate steps built long ago in the national monument I hiked last week – this was a clear trail, but there was no sign of humans on it. I initially assumed it was being maintained by cattle, but saw no tracks during the descent.

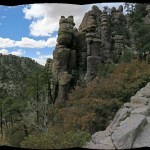

After spending the first half of the descent in mixed-conifer forest, I was surprised to suddenly emerge in a long stretch of mostly clear slope: an expanse of fractured bedrock with thin grasses and sporadic shrubs and small trees. This bedrock seemed to be mostly volcanic conglomerate containing colorful pebbles.

I approached the canyon bottom through open ponderosa forest, and could see it was lined with a broad, white debris flow from the 2018 wildfire that burned the crest at the head of the canyon. A very tall and slender narrowleaf cottonwood towered above the debris. And here is where I found the first cattle sign.

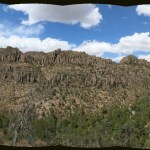

On the opposite bank of the canyon, I encountered a recently built stock fence, tight switchbacks that climbed the steep slope this side of the fence, and all the way up, cattle sign weeks and months old. Apart from the fence, I still hadn’t seen bootprints or any other sign of human use, so I began to assume that cattle were keeping brush off this otherwise abandoned trail, which had so far been really easy to follow.

Then, halfway up, I encountered the first of several broad swaths of bare, fractured rock. I was really enjoying the variety of healthy native habitats on this trail. The trail hugged the fence for a while, and I noticed how recent it was – maybe within the past few months. But fencebuilding in roadless country requires horses, and I’d seen no sign of horses, which can persist for up to a year.

The trail finally topped out in a vast area of bare rock, a broad shoulder past which I would enter a new watershed with views toward the area I’d discovered four years ago. I left the cattle sign behind and entered a segment of trail that was clearly being maintained by elk.

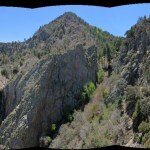

This next segment of trail traversed the steep south-facing slope below the crest of this range. On my right was a distinctive peak that I’d rounded on that previous hike, forested but with dark talus slopes on its north side.

The varied terrain continued, with the trail descending a scree slope at a 40 percent grade at one point, into a bare-rock ravine where I was surprised by a trickle of surface water.

This appeared to be an elk highway. But suddenly I came upon tiny fragments of orange rind, dessicated into thin, brittle shards. How quickly would they completely dry out? And how long would they persist on the surface without being scattered or buried by rodents, wind, rain, and erosion? We hadn’t had much precip over the winter but we’d sure had a lot of wind. I guessed they were over a month old, maybe many months – maybe they’d been left by the fencing crew. Maybe the fencing crew had been the only humans on this trail in the past year.

I’d stopped a lot, and climbed slowly on the ascents, and this hike was taking much longer than expected. I remembered the terrain ahead from the previous hike, and the trail junction I was trying to reach didn’t seem to be getting any closer. I’d been hoping to get to town before the market closed at 4 pm, but it wasn’t looking likely.

The trail had been climbing steadily, and I remembered it would descend before the junction. Just as I reached what seemed to be a high point, I stopped in frustration to check the topo map. After puzzling over it for a few minutes, I looked up, and behold! The old, partially collapsed trail sign was in shadow, right off the trail, less than ten feet ahead of me. I was already at my destination and hadn’t realized it! To celebrate, I reassembled the pieces of the sign as best I could.

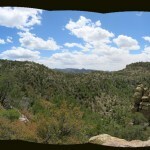

Wind had been picking up all day, and since the trail was more exposed than I’d expected, I was grateful for cooling breezes. What I love about this trail, in addition to the varied habitats, is that it’s a traverse overlooking endless, rugged, roadless terrain, with views that shift dramatically as you proceed from watershed to watershed.

But it was getting later and later, so I began hiking faster than was probably good for my knee.

When I reached the bald shoulder above the deep canyon, and began descending those seemingly interminable short switchbacks, all I could think of was the tall, steep climb on the other side. After reaching the bottom and starting up, I did have to take it slow in most places, but I’ve been working up to it for months now, gradually increasing the elevation of my hikes, so my wind isn’t bad.

After reaching the vehicle, I raced up, over, and down the crest on that terrible rocky road, and reached the market in town 5 minutes after closing, to find lights out and the door locked…

May 5, 2025

Imperial Monument

Not sure what it is that keeps making me want to venture far afield these days. I’m gradually increasing the distance and elevation of my Sunday hikes, but there are plenty of those near town.

The hikes take up less than half a day, so I spend more time driving than hiking. But I don’t mind the highway drives – they clear my head and allow my thoughts to wander freely.

I usually plan to grab an after-hike meal at some acceptable cafe near the destination. Since I get tired of cooking for myself, that’s an incentive in itself. But the main attraction may just be to escape from the stress that can overwhelm me at home. Driving two hours away seems like a mini-vacation.

For this Sunday, I picked an area based on a Mexican restaurant, then studied the map for nearby hikes. The most convenient was a small trail network in a National Historic Site that preserves the ruins of a pioneer-era fort. It’s hidden in foothills between two mountain ranges – the big one I hiked last week, and a much smaller one I’ve wanted to hike but can’t because most of it’s within private land.

The access road continues over a pass toward my second option, a National Monument on the west side of the big mountain range. In almost 20 years, I’d never explored either of these places – they’d been just too far for my typical all-day hike. The Historic Site turned out to feature some pretty mid-elevation Sonoran habitat, but the trails didn’t look as attractive as what I expected in the Monument, so I filed this area away for future reference and kept driving over the pass.

The country on the southwest side of the pass is rich-looking high-desert rangeland around 5,000 feet in elevation. It feels protected by the mountains to north and east, and remote, although the Monument is served by a roughly paved two-lane highway.

Halfway there I saw an isolated grove of tall conifers just off the highway. I immediately knew it was a cemetery – white colonists of European ancestry identify evergreens with eternal life, and will plant them if suitable habitat is not available. These trees appeared to be Arizona cypress, relocated outside their natural montane habitat. The sight evoked a wave of youthful memories; high school lovers are attracted to cemeteries for both privacy and the romantic pastoral setting, and the first night I spent with my high school sweetheart was in a tiny hilltop cemetery far out in the country, under a grove of pines much like this. Guess you could call us proto-Goths.

Back home, I actually found a web page about this cemetery, which belongs to a ranching family that has been prominent here since pioneer days. Two children of the founder were the first buried there, in 1885.

It’s a small Monument, roughly five miles square, encompassing some of the spectacular rock formations on the west side of the range. I normally avoid National Park Service properties, disagreeing with Ken Burns and the whole “American’s Best Idea” philosophy. The NPS view is that nature is best developed and managed for tourism, but the habitats they manage were actually stolen from native people who used them for subsistence in harmony with native ecosystems.

The tourists who visit national parks subsist on anonymous commodity food and other resources from distant habitats that have been destroyed by industrial agriculture. So National Parks are an integral part of the industrial society that destroys natural habitats and enriches elites.

Another reason I avoid NPS properties is the crowds. I normally encounter other hikers on roughly one out of ten hikes, but today I passed ten other hikers in less than half a day. And this is a remote Monument with much less traffic than most.

The weather was perfect – temps fluctuating between the 70s and 60s, depending on cloud cover and wind, which increased throughout the day.

Getting a late start, I took the first available trail, which started up a canyon bottom through the shade of a riparian forest of tall ponderosa pines, Arizona cypress, and big oaks – white or Emory. Unlike the narrow, overgrown, often abandoned trails I normally hike, this was a wide, laboriously built and heavily trafficked tourist trail. It soon climbed above the canyon bottom and I got my first views of the famous rock formations atop the opposite slope.

After a mile and a half I came to a junction with a branch that headed toward a side canyon. As developed as the first trail had been, this junction was even more impressive, with trail signs in massive stone foundations and dry-stone steps and retaining walls leading up the new trail. Frequent park visitors take features like this for granted, but to me they speak strongly of imperial power and entitlement, like the pyramids of Egypt and Central America. I assumed they had been built by the young men of the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps.

Turning into the side canyon, the trail took me directly under spectacular rock formations that were often obscured by forest.

In less than a mile, the trail crossed the head of the canyon and began to climb switchbacks toward the crest. And approaching the crest, the trail became a series of stone steps, constructed with enormous effort by those young men, a hundred years ago. The final climb through the rimrock formations was like something out of the Lord of the Rings movies.

Storm clouds were rapidly covering the sky, and I had to pull on my shell in the sudden cold.

The trail topped out on a rolling plateau where fanciful outcrops rose sporadically out of pine and oak forest. I figured I’d gone about three miles, which, doubled, would be the maximum I wanted to put on my recovering knee – so I turned back, hoping for rain along the way.

As usual, I was paying more attention to my immediate surroundings on the way back. I realized that this would be a perfect place to drop acid – one of the two best I’ve ever seen, along with Arches in Utah.

I noticed how bedrock features had been used or even reshaped by trail builders, and marveled at long drystone retaining walls that had been built below steep sections. Crossing a talus slope, I estimated that many of the stones that had been moved and meticulously placed weighed over three hundred pounds. That long-ago CCC effort was truly like the building of the pyramids! As a kid, I’d taken park features like this for granted, but now I could only see them as reflections of imperial might, the will of the nation imposed on the landscape “for all time”.

I prefer to live lightly on the land, hoping to “leave no trace”.

The final group of fellow hikers that I passed was a family of three with a dog – on leash. Reviewing the NPS trail guide later, I noticed that dogs are not allowed on this trail. That family was training their preteen son to disregard both laws and the common good. Best to start them early, I guess.

On the drive to town for my Mexican meal, I could see rain falling over the pass, and ahead, dust storms had been stirred up by high wind. My little vehicle, taller now with the suspension lift, was hard to keep on the road.

It was even harder crossing the playa the next day, when the wind suddenly carried a dust storm across the freeway, briefly eliminating visibility and driving some vehicles off onto the shoulder. By the time I reached town, I had just missed our first rain in months.

May 3, 2025

Bringing the Family to the Rocks

Some of my friends lost their parents years ago, and never became actively or intimately involved in their late-life care or affairs. Other friends envisioned their retirement as a liberation, hoping to escape the expensive, crowded city where they’d spent their professional lives to some scenic, idyllic rural paradise like the one I found nearly 20 years ago.

But if their parents were long-lived like mine, they might’ve then found themselves trapped in the city, caring for their parents instead of enjoying the freedom of their retirement. Their own health, fitness, or financial security may even begin to decline, eroding those dreams of an active life in a healthier location.

Eighteen months ago, when I found myself suddenly responsible for the care and affairs of my elderly mother and disabled brother, I faced two major obstacles. First, after decades of creative frustration and years of joint pain and arduous rehab, my quality of life now depended on having all my time free for creative work and wilderness exploration. I’d become desperately selfish.

And second, my family was 1,500 miles away.

Who Should Move?

Who Should Move?When I told people I was helping my family, the immediate assumption was that I would move to be with them. But mother and brother were living in the center of Indianapolis, a sprawling metro area of nearly a million people, in a monotonously flat, highly developed landscape with neither mountains nor wilderness. An expensive place to live and a dangerous place to drive, with virtually no traffic enforcement, increasing lawlessness, and rising traffic fatalities. Over and over again, I had to explain that I’d spent years searching for this refuge far from crowds and traffic, where I could live cheaper, healthier, and closer to nature and wilderness. I couldn’t conceive of leaving that for a big city – especially in a flat landscape with no wilderness.

It’s common now for families to be geographically fragmented, hundreds or even thousands of miles apart. If it was inconceivable to leave rural New Mexico to care for parents in a distant city, what were the options? For the first year and a half, the only option for me was constant travel, and I found myself spending more and more of my time back there, until last winter when I lived in Indianapolis most of the time. That was the breaking point for me – traveling and living in that crowded, expensive place, caring for my family instead of making art and hiking the wilderness, was destroying my physical and mental health and fitness.

Objections No Longer Valid

Objections No Longer ValidSo I talked it over with mother and brother, and instead of the superficially easier option of moving me to them, we decided to move them to me. I thought this might be something for others to consider! Trapped in a crowded, expensive metro area caring for your parents and dreaming of some distant time when you can finally escape the city – what about the option of moving the whole family to a cheaper, healthier place?

The arguments against such a move are obvious. How could you subject your elderly parents to the shock of leaving their familiar environment for a strange place where they’d be surrounded by strangers? What about other family members, and friends, who’ll be left behind? What about the significant loss of healthcare resources in a rural region far from the vast resources of a metro area? And what about the cost of the move itself?

In my family’s case, moving became an option only gradually, as we all came to realize those were no longer valid objections. Mother and brother had become increasingly isolated and immobilized by disabilities, so they were no longer an active part of their urban environment and community. The frustration they were feeling made them more open to a move to a completely new environment which might offer new friends and experiences.

Yes, the healthcare resources here are extremely limited. But this is primarily a working class family community, and in that social class, family unity means more than advanced medical care or high-end services. That’s a value system we could all learn from. Our rural small town is far safer than the big city, and in the long run, occasional travel to the nearest city for specialist care is much cheaper and healthier than living there full-time.

Yes, the move is expensive, but the one-time costs are more than offset by the ongoing, long-term savings. Mom’s flight had an overnight in Phoenix, where a homeless man slept on the sidewalk across from our room – at the foot of a corporate bank tower – a reminder of the dehumanizing, inequitable urban environment we were leaving behind.

Move Already Paying Off

Move Already Paying OffOur 98-year-old mother suffers from severe hearing impairment, hypertension, mild incontinence, chronic urinary infections, physical weakness, chronic anxiety, and mild memory loss. Onset of chronic UTIs last summer resulted in hospitalization, confinement to wheelchairs, and total loss of independence in care facilities. She finally began to recover from the UTIs last December, walking again and regaining memory and mental acuity.

Our solution was to fly her here with a hired nurse companion, to arrive at an “assisted living” facility which is like a funky motel, with meals and 24-hour aides to administer meds and do personal care and housekeeping. Her new room is bigger than the room she left in Indianapolis, with a private bath instead of the shared bath she had back there – and for half the monthly room and board.

Reclaiming Independence

Reclaiming IndependenceThe transition was hard on both me and our mother, but the long-term advantages are already clear to both of us. She loves her new caregivers. She actually has more access to care than in the big city, where resources have deteriorated since COVID. She has much more social interaction and a better diet than when she was living at home. She loves nature, and with me nearby to take her on outings, her quality of life is dramatically improving.

For our mom, losing her independence during the past year has been much harder than moving across the country. She hates to be so dependent on me, and it’s inspiring to see the ways in which she resists the process of aging and reclaims her independence whenever possible. She fights memory loss by capturing her experiences daily in a journal, and a couple of weeks ago she decided to get her hair dyed red – not like most older women, in an attempt to hide her gray hair and look younger, but to show she’s still a creative woman who can make her own decisions.

My brother, morbidly obese with a chronic leg injury, still drives but has become mostly confined to home, where he gets an aide twice a week, and his social life takes place online. I’m looking for a subsidized apartment for him, and we plan to use a “bariatric transport” company which will move him here in 24 hours of continuous travel in a specially equipped van.

Going to the Rocks

Going to the RocksDuring recent years, as I’ve shared my hiking dispatches with our mother, she’s become obsessed with rock formations. She’s endlessly curious and wants to know what they’re made of and how they got that way. When I visit her, she always wants to “go to the rocks”. So on Friday, I took her on a picnic to a state park a 45-minute drive east of town – a spectacular place I still hadn’t seen myself in all the time I’ve been here.

Cowboys and Girls

Cowboys and GirlsOn the way back, I decided to take a different route, up the river valley where I’d first fallen in love with this area, while staying with new friends at their hot springs “commune”.

That turned out to be a lucky decision, because rounding a bend in the road, we came upon a scene right out of the Old West: cowboys and girls riding hard down a hillside, driving cattle to a corral. There were between six and eight riders, most of them teenage boys and girls, led by adults. It happened so quickly, I had to make a U-turn and pull off the road just as they were finishing up out of sight, so my mom could get a glimpse and I could snap a crude photo.

Ranchhands on horseback is a sight you almost never see in these days of ATVs and UTVs, and we just happened to stumble upon it! A typical day in the Land of Enchantment.

April 28, 2025

Dry Springtime

Over to Arizona again, this time to climb the first couple miles of my favorite long hike in the range of canyons. Clear skies, temps in the mid-70s, and bone dry everywhere.

There’s a 1.5 mile forest road leading to the trailhead. Most people park at the entrance and walk, because the road is completely lined with big loose rocks that would likely destroy their vehicles.

The road is gated to keep cattle out of the wilderness, but some fool – probably an ignorant city dweller – had left it open. Because I wanted to hike the trail not the road, I drove all the way to the trailhead, at less than 5 mph over those rocks.

Again, it recalled my long-standing ride quality quandary. Shortly after buying this vehicle, on a 2019 camping and hiking trip with a friend, I’d literally become a nervous wreck trying to keep up with his new Toyota FJ on rocky backcountry roads. He rocketed ahead of me going 45-50 mph, while I was getting shaken to pieces doing 12 mph.

I ended up spending $1,000 on new shocks, with no change to the ride. Eventually, I did this entire suspension upgrade, and now, if anything, it rides even rougher.

After buying a pair of noise-canceling headphones, I learned that what stresses me out is not the ride, but the noise of the vehicle slamming or rattling like a machine gun over every tiny imperfection in the surface.

And after scouring the forums for this popular vehicle, I’ve concluded that ride quality is complex and highly subjective. Some people say this vehicle rides rough, while others with the same model claim it’s not a problem.

Eventually, I recalled field trips I made back in the 90s and early 00s with a scientist friend who drove old trucks owned by the Department of Fish and Game. Off the highway, he used to drive the rest of us nuts by never exceeding 15 mph – he said he was extending the life of the vehicle by reducing wear on the suspension. Conclusion: there’s no objective standard for ride quality, nor is there a proper speed for driving rough roads.

The trail starts out climbing the upper valley of a creek, through pine forest burned at low intensity in the 2011 wildfire. I found old cattle sign here, unfortunately showing that the gate had been open for weeks, if not months. Cattle were likely all over the wilderness by now and would be impossible to eradicate.

A half mile into the wilderness, the trail begins switchbacking up to the dry waterfall, which is over the ridge at my left, in the next drainage south. With my bad knee, I hadn’t been able to hike this trail in over a year, but someone had cleared it since the last monsoon. I did find stretches of trail, and nearby ground, that had been turned over by an animal looking for insect larvae, and since I found no bear sign, concluded it must’ve been coatis.

Surprisingly, there remained an algae-choked trickle of water over the falls.

One attraction of this climb is the views it reveals over the inner basin of the mountains. The next stage, the climb to a saddle overlooking the upper, hanging canyon of the creek, involves a series of short, steep switchbacks, each one with a better view.

At the top, my hat was blown off by a torrent of wind down the hanging canyon. It would’ve been a great place to hang out otherwise. But it was past noon and I was getting hungry – part of the plan was to get a late lunch in the cafe at the entrance to the mountains.

After descending all the switchbacks into the final creek valley, I came upon a hiker just starting up the trail. He said he’s from Alaska – a snowbird – and lives here seasonally. We discussed my knees, the weather, and the drought, and he asked me about the condition of the Emory oaks, which I hadn’t really focused on.

On the drive out, I noticed the leaves on the oaks were mostly dead. Unlike most deciduous trees, Emory oaks drop and regrow their leaves in late winter and early spring. I’d noticed them changing but hadn’t looked for drought effects.

In the desert, I’m used to the foliage of shrubs drying up as a reaction to extreme drought. What freaks humans out is seldom a disaster for resilient wildlife and habitats.

I avidly attacked an excellent burger in the cafe, but I’d just gotten over a week-long bacterial infection and my stomach wasn’t prepared. By the time I started the drive home I had terrible stomach cramps that lasted for hours.

Then on the drive north to the dry lake, I entered a dust storm. The interstate remained open to the turnoff for my hometown, but it was closed past there, so on the final leg of my drive, climbing into the mountains, I was joined by an endless parade of big rigs and city drivers, all of whom were angry at being detoured hours out of their way. The only thing that kept me relatively calm was the pain meds I’d taken for knee and shoulder.

April 21, 2025

Roadside Attraction

It’s a remote two-lane blacktop through vast, lonely, dry ranchlands punctuated by stark buttes and small mountain ranges. Most who drive it are commuting to or from the giant mine, isolated on another road that branches off north. Preoccupied with concerns of job and family, with little thought to the barren country they routinely race past.

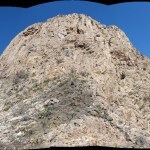

For humans, this dry country is defined by the river that allows farming on its occasionally broad floodplains. But to shortcut a bend in the river, the highway rises onto a plateau, and near the eastern end of this plateau, the road passes below a distinctive peak surrounded by sheer bastions of rimrock. That peak had always beckoned me, but until now it seemed too short a hike to justify the hour-and-a-half drive.

From the highway, the rimrock looks unclimbable, so I researched it online. As I look for more obscure hiking areas, what I’m finding is that my only predecessors in these overlooked places are the “peakbaggers” – the geeky, competitive subculture that cares more about numbers and life lists than nature, beauty, or even athletic challenge. The number that matters to peakbaggers is topographical prominence: the height of a peak relative to the lowest contour line that completely encircles it. The goal of a peakbagger is to climb the most peaks with the most prominence, verify their ascents, and share them with their community for bragging rights.

The vast majority of peaks don’t have trails to the top, so unlike regular hikers, peakbaggers spend most of their time bushwhacking rather than following trails. But since prominence is their goal rather than elevation or distance, peakbaggers typically avoid wilderness areas within sprawling mountain ranges, where tall peaks are connected by tall ridges, drastically reducing their prominence. So a broad distinction between hikers and peakbaggers is that the former use trails to hike or backpack long distances across varied terrain, while the latter drive to the base of an isolated peak, race up it, log a GPS coordinate, and race back down.

My recent experience reinforces this distinction. Hikers are simply not discovering many of the places I’m hiking these days, because they’re not maintained or known as hiking areas. They lack trail networks. The only people who are hiking them are the peakbaggers.

In this case, their GPS tracks had shown me the route around that sheer rimrock.

Despite being right off the paved highway, this is such an overlooked area that the maps don’t even show the high-clearance 4wd track that accesses the route. It climbs up a shallow outlying ridge and dead-ends at a hilltop clearing. A short distance above I could see a fence traversing the slope toward a ravine that divided me from the rimrock peak, and I started by following that fenceline toward the ravine.

Another clear day, with less wind, and mild temps. Lots of cattle sign, but nothing recent. I love this habitat along the state border, combining species and genera familiar from the Mojave, with Sonoran plants like ocotillo and honey mesquite. And the rocks here have a subtle variety and beauty it’s easy to miss while driving past. In fact, the entire landscape becomes more beautiful the more you focus on the subtle contrasts.

The head of the ravine is a small basin on the back side of the mountain, where minor draws converge from the rimrock above. My route would ascend a hump between two of these draws, punctuated by rock formations that mostly hid the peak I was aiming for.

Like most of our volcanic terrain, it was slow walking, picking my way between sharp rocks, cacti, and yucca, but it wasn’t annoyingly slow, and the weather was perfect. At the head of the hump, I emerged onto a small ledge, and beyond that, the real climb began – up and across the steep slope below the rimrock, toward what I assumed would be a gap through which I could reach the actual peak.

I’d been sick the whole night before with I’d assumed was food poisoning. I’d felt better in the morning but still wasn’t sure I was up to this climb. I was ready to give up at any point, but I took it slow, and as I rounded the slope, it gradually became clear that the rimrock ended in a sort of cove between here and the peak. The peak itself rose out of the end of the ridge formed by the rimrock.

The gap in the rimrock turned out to be a narrow ramp, and at the top I emerged onto a narrow, juniper-dotted mesa, with the peak at its far end.

The peak, only a couple hundred feet above this mesa, is guarded by bare rock walls, but I could now see what appeared to be a climbable gap. The final slope was the steepest I’d faced yet, but it was lined with cool, spherical rock nodules or concretions, and climbing straight up, before I knew it I had reached the gap and was levering myself over the final boulders to the very top.

This was a real 360 degree peak – not like one of those rounded, forested mountaintops that dominate our larger ranges. The top, an irregular platform of blocky boulders, was roughly 25 by 50 feet, with two separate federal benchmarks, and a sheer drop on all sides except the gap I’d climbed through.

From up there, I really fell in love with the subtle patterns on the landscape: landforms, rock outcrops, bedrock transitions, and vegetation. Impossible to convey in a photograph. I wanted to stay for hours just soaking it all in. But I was trying to regain muscle mass, I’d done three full workouts during the week, and if I left now, my lunch would still be 3 hours late.

My knee must be improving, because despite the steepness I made it back down to the mesa quickly and safely. From there it would be a piece of cake. And not a single cow or bull, as far as the eye could see. This was quickly becoming my favorite short hike in our area!

As usual, on the way back I was paying more attention to the details. The lichen here is fantastic, and the ocotillos more than made up for the early-season lack of wildflowers.

Following the ravine and fenceline back to my vehicle, I took a shortcut that led me across a slope of dense, sharp volcanic cobbles – just enough to keep it from being a walk in the park.

I’d planned this trip assuming I would get a hearty lunch at the cafe in the Mormon farming village on the edge of the floodplain – but it was closed for Easter!

And when I finally got home in late afternoon, and warmed up a batch of leftover Mexican food, I discovered it wasn’t food poisoning after all – I had a case of stomach flu, and would start the week sick, unable to eat, so weak I could barely stand. Gotta take the bad with the good…

April 13, 2025

Pollen Peak

The vast wilderness area north of my hometown encompasses canyons and mountains that rise to a nearly 11,000 foot crest in the west. That’s where most of my all-day wilderness hikes have taken place, accessed via the highway that leads west out of town and then north past the wall of mountains rising on your right.

But I’ve become more and more curious about the lower mountains that rise to the left of that highway, along our border with Arizona. Most of them lack wilderness protection and are grazed by cattle from bottom to top. But they do host an old network of unmaintained trails, and the area is so far from cities that these trails are seldom used by humans.

There’s one small mountain group, at the center of a broad network of intersecting trails, that I’ve been especially curious about because although it’s easy to find on the map, I’ve never been able to identify it from the highway, and it’s really hard to get to. First you have to ford a river, then you need to drive almost 15 miles uphill on increasingly bad ranch roads. The overall distance from town is less than 80 miles, but I figured it would take at least 2-1/2 hours one-way – more than I can justify for an all-day hike.

But now that I’m doing short hikes, it suddenly seemed doable.

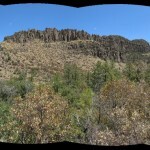

In this severe drought, the river was dry, so that was no problem. The main ranch road climbed to a mesa, where immediately to my right appeared a spectacular canyon with sheer basalt walls.

A little farther upstream, the road crossed the dry wash above the canyon and climbed to a higher mesa, from which I could see the ranch house in the valley to my left. And I could finally see the mountains I was heading for: a higher pyramid-shaped peak at left and a lower rounded peak at right, connected by a low ridge.

The road was graded all the way to the Arizona border, where I found a crude gate. On the other side the road was just a trail over volcanic rocks. I opened the gate and waited for several cows to usher their new calves out of my way.

The road past the gate turned out to be the rockiest I’ve ever driven. No way would I have been able to drive it before my recent suspension lift. Mile after mile, it just kept getting worse: big, sharp, loose volcanic rocks, with chunks of bedrock sticking up a foot high in places. My maximum ground clearance is now a little over 11 inches, so I had to pick my lines carefully. I couldn’t go more than 5 miles per hour in most stretches, and I often had to slow to walking pace.

The suspension upgrade hasn’t improved the ride quality at all, which is kind of what I expected. The farther I crawled over these rocks the less sense it made to drive rather than walk – but the trailhead was still miles away, and I wanted to at least reach the lower of the two peaks, which would be over a mile from the trailhead.

When I figured I was a half mile from the trailhead, I found a place to pull off the road. That turned out to be fortunate, because beyond here, the track got even worse, climbing at a perilous grade on even bigger loose rocks, and there were no more places to turn around before the end.

I’d been expecting a hot day, but it turned out to be very windy. It was hard walking on those loose, sharp rocks, and the track got continuously steeper, until it topped out on a shoulder of the rounded mountain, with the trailhead just ahead.

Almost as soon as I started up the trail, I had one of the worst allergy attacks I’ve ever had. I’d packed Zyrtec that morning, but foolishly left it in the Sidekick, which was now a half hour back down that hill of loose rock. So for the next couple of hours, I used up the bandannas I carry in my pack, sneezing constantly, so violently I had to stop walking to hold my balance, my nasal membranes burning, a mucus factory working overtime.

At the same time, clouds were moving over and the wind was increasing, so I had to pull on my windbreaker and cinch my hat down tightly.

Along the way, I distracted myself by examining the spectacular views north, and as I crested the first peak, northwest. The top had burned patchily in past fires, but still hosted tall ponderosas, and eventually I got a narrow view of the taller, pointed peak a mile south. That’s where I stopped to turn back, figuring I’d gone at least a couple miles.

On the way back, despite my constant, violent sneezing, I managed to clamber off-trail several times to shoot panoramic photos over the low country between here and the higher mountains to the north. All that wild country was beckoning me, and hopefully I’ll be able to hike it someday.

Past the trailhead, I began picking my way back down that steep slope of loose rock, and immediately realized it was too dangerous to ever drive in my vehicle. Regardless of ground clearance, if I lost traction and slipped, I was bound to damage something underneath on either a loose rock or a sharp outcrop of bedrock. I don’t want to think about how long it would take to get a tow out here – I might have to pay Matt’s Off-Road Recovery to drive over from southwest Utah, and I’m not confident that even Matt could make it up this road.

But after reaching the Sidekick and bouncing back down the road at little more than walking pace, I began to get better and better views east toward our high mountains. I’d taken a Zyrtec and a pain pill – usually very effective at drying my membranes.

I kept wondering what was triggering my allergy. Both oaks and pines can bloom in spring, and both were all around, stirred up by the fierce wind. I’d had a bad attack in town the other day, but nothing like this.

At home, I had to take a second Zyrtec – not usually recommended – and a second pain pill, but despite running my air purifier on high and flushing my sinuses with the neti pot, I had yet another bad attack within a couple hours. Can’t remember anything like this before!

April 6, 2025

Glorious Clouds and Rocks

It had snowed yesterday – just flurries in town, but I was looking forward to driving northwest for a view of fresh snow on our high mountains. Out of curiosity, I checked my photos of Aprils past. In 2012 it snowed here on April 14, in 2017 it snowed on April 1, and in 2021 it snowed on April 29. So not that unusual.

When I left the house it was freezing outside and I had to scrape frost off the windshield. I was planning to hike the first mile or so of one of my favorite wilderness trails, and on the drive north I could see snow on the slopes down to 7,000 feet. But most of the crest was obscured by a layer of clouds.

Along the highway, I passed hunting hawks of different species. Turning east off the highway, I followed the paved road up the edge of the broad floodplain of our famous river, then climbed the rough dirt road to the mesa at just over 5,000 feet. Eleven miles north I turned east again on a ranch road which drops into the valley of a big creek – now dry outside the mountains.

The creekside ranch apparently has a new owner, who has posted “Beware of Dog” signs every hundred yards for the two-mile stretch of ranch frontage. Must be quite a dog!

With its long approach on rough back roads, this trail doesn’t get much use – last entry on the trailhead log was more than two months ago, and the only tracks I found were from cattle.

Towering white clouds were forming and growing above as I hiked the rolling terrain, crisscrossed by shallow washes and crowded with Emory oaks and alligator junipers.

After traversing the maze of washes, the trail climbs gradually to a high bench before hitting the first slope of the mountains. My destination was a sheer rock outcrop that forms a natural dam across a steep canyon. It was really farther than I should’ve hiked at this stage of my knee recovery, but it provides a great view over the mesa.

And with the towering white clouds against the deep blue sky, and glimpses of fresh snow on the crest, this was the most glorious day for a hike I’d seen in a long time!

The sky just got better and better on the way back, with cloud shadows drifting across the slopes and occasional rays of sunlight glistening like diamonds on far-off patches of snow.

I grew up in the rural Midwest – a place whose wild, native history was totally erased long ago. Then, I spent most of my adult life in huge metropolitan areas – Chicago, the San Francisco Bay Area, and Los Angeles – participating in a series of cultural and technological revolutions that defined historical eras in our colonial society.

And now, I’m blessed to have found a refuge far from the colonial capitals and urban sprawl, far from the centers of imperial wealth and power, at the edge of this vast mountain wilderness.

March 30, 2025

Short & Steep

Continuing my knee rehab, I’m looking for 2-mile hikes with increasing elevation gain. And this weekend, I realized there’s a nearby 8,000 foot mountain that I’ve always avoided because the hike to the top and back is only two miles. It’s our most iconic mountain because its profile suggests a bear.

Since it’s only a 2-mile hike, I hadn’t really studied the topo map, and it wasn’t until I started climbing that I realized this is by far the steepest hike in my repertoire – an average 22% grade from bottom to top. So not so smart for my knee.

It’s just tall enough to host an island of ponderosa pines at the top, so one of the highlights of the climb was the final transition from pinyon-juniper-oak to ponderosa forest.

And of course there was a decent view, to northeast, northwest, and southwest.

When hiking downhill with patellar tendinitis, it seems the important thing is your gait. You need to use your whole foot, landing on the heel and rolling forward to grip with your toes. So I tried that on the entire 1,054 foot descent. It was still hard on my knee, but hopefully not as hard as if I’d descended mindlessly.

March 23, 2025

Five Fires in One Mile

After a week’s hiatus, here’s a short Dispatch from a short hike (still rehabbing knee).

Pics are dull under a cloudy sky, but after the hike I added up all the wildfire scars seen today and realized it’s actually kinda interesting.

The hike begins at 7,200 feet elevation, at the eastern foot of a long east-west ridge, in the narrow, pine-forested canyon of a seasonal creek. It traverses through pleasant, open ponderosa forest thinned by a 2020 fire that started at the west end of the ridge and mainly burned on the crest and the north slope – but surprisingly sneaked around to burn at low intensity at the southeast end.

The trail climbs the east end of the ridge toward an isolated outcrop of striking, bulbous white rock, where you next enter a gentle, exposed slope lined with ferns, locust, and scrub oak that is the small scar of a much older high-intensity wildfire that killed all the pines in this spot. That wildfire opened up dramatic views to east and south.

Climbing to the north side of a rocky peak, the trail briefly re-enters intact forest, which is where I turned back today, at a little over 8,100 feet elevation. But through the trees, I could see west toward the high-intensity burn scar of the 2020 fire. Temps were in the 60s today, but I found patches of snow in shaded spots from 7,000 feet upwards.

Turning back and emerging from the forest, I could see south across the canyon toward the apocalyptic moonscape left by a 2014 fire, and west to the Black Range, devastated by high-intensity mega-wildfires in 2013 and 2022. I’ve hiked all these burn scars extensively.

March 9, 2025

Dangerous Beauty

For almost 35 years, I’ve hiked to the plateau above my land in the Mojave Desert, a beautiful oasis with a prehistoric ceremonial site, and considered that the most dangerous hike I do. It requires climbing 400 vertical feet straight up a 67 percent grade on a surface of loose dirt, loose boulders, yucca spines, branching cholla cactus, and big, spreading acacia shrubs covered with thorns. I sometimes step on boulders heavier than me that I expect to be solid, and have them tip over under my feet. In places the easiest route is up ramps of crumbly granite bedrock, where a slip would result, at minimum, in torn flesh and broken bones. And I almost always make that climb alone, in a place with no cell signal.

On the way to one of my favorite hiking areas along the Arizona border, I pass a small mountain range with low granite peaks, cliffs, and boulders that reminds me of my mountains in the Mojave. The peak of the range has always intrigued me, because from the highway it looks unclimbable, a spire of solid rock. And while researching the area online, I was surprised and excited to learn there’s a population of desert bighorn sheep there.

The map shows a dirt road running up a southwest canyon toward the foot of the peak, and I wondered if maybe I could climb from that to the base of the spire and traverse around to the back, to see if it might be climbable on the north side.

We’d had a dusting of snow in town the previous day, and as I drove over there, I was surprised to see quite a bit of new snow on the high mountains peeking over the horizon. The drive includes about 15 straight miles on the interstate, which was a good test of the Sidekick’s recent alignment. And the unmaintained dirt roads to the foot of the peak turned out to be a good test of the bigger tires and suspension lift.

I’m under so much stress that I’m barely sane, and shortly after turning off the highway, I mindlessly took the wrong road toward the peak. It ran up a wash lined with deep, dry sand where I was immediately afraid of getting stuck, so I shifted into low range 4wd. I plowed a mile up that sandy wash, on edge the whole time, not realizing it was the wrong road until I’d reached the very end.

Back on the main road, I tested the Sidekick lift on deeply eroded and rocky stretches, and never bottomed out. It was great not to be stressing over the right line to take all the time. The road I needed, up the canyon to the foot of the peak, hadn’t been driven recently, and turned out to be as bad as the abandoned mine roads in the Mojave. As in the Mojave, the alluvial fan was lined with creosote bush, and there was even a deep dry wash next to the road just like in the desert. The peak loomed higher and more forbidding as the walls of the canyon closed in, but the road kept climbing and climbing, much farther than I’d expected.

I finally sensed the end was near, and backed off into a small clearing to scan the slopes ahead. They looked far too rugged to climb, and that deep wash, lined with big prickly pears, separated me from them anyway.

But farther up the canyon it looked like there might be a more gentle slope I could traverse left toward the sheer base of the peak – the direction I was hoping to explore.

I set off up what was left of the road. It soon ended – without space to turn the Sidekick around, so I was glad I’d stopped early. Here, floods had left a wall of rocks above the wash, but I could see some kind of narrow, overgrown corridor leading up to the right of the rock wall. I tried to follow what looked like an old mule trail, but in many places it was choked with cactus.

In the meantime I was scanning that slope across the wash that I’d hoped to climb. No dice – the lower part was too steep, and the wash was blocked by spreading prickly pears.

Above, I could see a little pile of mine tailings, and suddenly I emerged into a clearing that featured the rusted steel frame of a bench seat from a pickup truck. The path continued, and soon I saw a gap where I might be able to cross the wash between prickly pears, and hopefully climb to the mine tailings. It looked like I might be able to use that to bypass the slope I’d originally hoped to climb.

I immediately discovered this was dangerous terrain to climb – as dangerous as that plateau hike I make in the Mojave, with the same features. The slopes here were loose dirt and loose rock alternating with steep ramps of rough bedrock, and the way was blocked again and again by shrubs with inch-long thorns, prickly pear, and big agaves that would impale you if you happened to slip on a loose rock.

But atop the tailings pile was a flat ledge and the mouth of a mine.

It was a shallow mine, and fairly recent, with oxidized plastic containers and a rusty old can of insect spray – maybe from the 60s or 70s. Like most mines, it had some interesting rocks piles outside the opening – surprisingly similar to rocks in the Mojave.

The mine was on a slope opposite the one I’d hoped to climb, across a deep, narrow gully choked with boulders and cacti. As I picked my way from the mine toward the gully, I could see that this slope was much rockier, and got rockier still higher up. And the rock looked exactly like the rare metamorphic rock in the canyon on my Mojave land, which I’d never seen anywhere else.

If I wanted to continue this hike, I was going to have to climb this steep, thorny slope. The metamorphic rock has a rough, sharp texture which can be good for climbing, but at this level it was too steep, so I had to climb the loose rock – exactly what the bighorn sheep had been doing. Sometimes I was able to follow their route, but the higher I climbed, the more dangerous it got.

I was hoping to climb above the gully and traverse left onto the easier slope, but above the gully my way was blocked by a broad ramp of bedrock at about 40 degrees. It was just too dangerous to traverse.

So I turned right, where across a rockfall of sharp boulders, I could see a long, steep bedrock ramp leading up to the horizon, where there appeared to be a juniper beckoning me. I picked my way carefully over the boulders, and stepped out onto the ramp. The surface was like a really coarse carpenter’s rasp – a fall would tear your skin off down to the bone, and sand your bone down to bone meal. Traction was really good for climbing up, but how would I get back down? I blocked out the thought.

The ramp only took me part way – the rest of the climb was in loose dirt and loose rocks, winding my way between thorny shrubs, cacti, and agaves. I was more and more convinced this was a terrible idea and I’d end up badly injured or dead, but I was on autopilot and couldn’t give up.

I finally passed the little juniper, and emerged on a small ledge with a killer view. There was still a higher slope leading up to the sheer base of the peak, but I wasn’t going any farther today. I had little hope that I’d be able to get down from here intact.

It was lunchtime, and I snacked on homemade trail mix. I’d hoped to reach the cafe in the Arizona mountains across the big basin, but I was half convinced my life would end below this peak.

I’ve never been so cautious on a descent. I inched down that long ramp on my butt. I never want to tackle a climb like that alone again – but taking a slightly different route, somehow I got down without slipping or falling once.

The Sidekick did really well on the drive out. It makes a hell of a noise, but I wore my noise-cancelling headphones and drove faster as a result.

It was after 2 pm when I reached the cafe. Starved for protein after working out during the week, I ordered the steak instead of my usual burrito. My knee was killing me, so I took a pain pill.

This was not the kind of hike I’m supposed to be doing, to recover from the knee injury. Like I said, I’m barely sane. It’s like I’m on autopilot, blindly doing the same dangerous things I did at half my age – but now my family depends on my survival.

A half moon was rising in front of me as I drove home in late afternoon. I’d only hiked four fifths of a mile out and back, with 566 feet of elevation gain. An incredibly dangerous place, but incredibly beautiful.