Max Carmichael's Blog, page 2

September 21, 2025

Rain Over the Basin

We still had a few hot days ahead, and I’d decided to make the long drive north to the volcanic plateau for a level hike through aspens, fir, and spruce. But on my way out of town I pulled over, realizing I really wanted to do the shorter drive southwest to the range of canyons. I didn’t know what hike I would do there, but the drive – on the Interstate and straight, lonely highways – would be so much easier.

I arrived at lunchtime and had a delicious brunch in the cafe first. Then as I drove back into the basin I encountered crowds of birders, and realized I would need something remote and unpopular.

The gnarly road to my favorite trail, lined with big loose rocks, passes a side trail that I’d partly hiked from the opposite direction last year. It’s a boring trail that I’d always avoided before my knee injury – it just goes from road to road, traversing the western slopes of the basin, without any sort of interesting destination. Its only redeeming feature is the occasional views east over the basin.

Storm clouds were gathering over the range, so I might even get lucky and get rained on!

Before heading over here, I’d considered this trail, but rejected it because it would have too much elevation change for my knee. But at this point, what does it really matter?

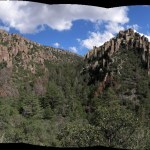

The remote, boring trail was overgrown with agaves and catclaw acacia. It hadn’t been maintained in years, and there was no evidence anyone had hiked it this year. I walked in and out of dark cloud shadows and narrow ravines. The trail was lined with beautiful wildflowers, some of which looked new to me.

At the halfway point, I rounded a bend and saw a big outlying ridge across a deep ravine – I knew the trail would start climbing that ridge on switchbacks. But it seemed to take forever, first to cross the ravine, then to climb the long switchbacks. In the meantime, I was treated to thunder and the sight of rain, three miles east across the basin.

The whole mountain range was teeming with butterflies – mostly black – but they were too shy to photograph.

I was wearing the knee brace, which masks the pain, but I was sure I was going to suffer later when I took it off. I’ve got it set to allow 45 degrees of flexion, and with that, I can hike normally except on steep stretches. But without the brace, I can’t stand to put any weight on the knee while it’s bent. This is how it’s been for almost 17 months now.

What a boring trail! But what a beautiful day, in a beautiful place. In the past I would’ve stayed overnight, but I have to watch my expenses now that the whole family depends on me.

September 15, 2025

When Rocks Were People

After sixteen months and three tries, our local doc’s attempts to fix my knee have failed again. I can’t waste more of my precious life on failures. Time for the big-city options, an hour’s flight or up to a five hour drive away.

In the meantime, I’m no longer worried about making it worse. What limits me is the harder the hike, the longer I’m immobilized with pain afterward.

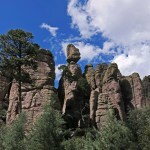

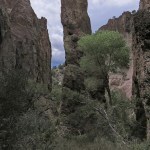

The hike I chose for this Sunday was in the national monument over in Arizona. I wasn’t looking forward to the crowds, but the habitat would be spectacular, the distance manageable, and the elevation changes should be okay for my knee.

This trail starts on the crest, drops down through the rocks into a series of small, narrow canyons, then loops back up to the start. Pulling into the parking lot, I had to pee really bad, so I stepped behind a tree and checked to make sure nobody could see me.

Five minutes later, as I was placing the sunshade in my windshield, I heard yelling and noticed a car passing me, leaving the parking lot. I walked out, asking “What did you say?”

The small SUV was already past, but a middle-aged matron with beehive hairdo leaned out the window and yelled, in a nasal East Coast accent, “If you gotta pee, go behind a tree where nobody can see ya!” I laughed, but I started the hike feeling like everything was against me – my knee, my doctor, the square tourists in this formerly wild place that had been sanitized by the empire into a recreational enclave.

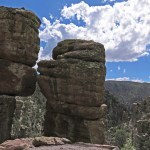

So much disappointment saps your motivation. As I passed one group of out-of-shape tourists after another – cheerily agreeing with them all that it was a beautiful place and a beautiful day – I asked myself again and again what I was doing there. The miles of stone stairways winding through the rocks, result of Herculean labors by the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps, actually made the trail harder to negotiate with my knee injury. Our hallowed National Park Service has even provided catchy names for natural features, handed down from English imperial history. I compulsively shot photos for a Dispatch, without really seeing what I was shooting.

I normally hike in remote locations where I’m totally alone and am often the first visitor in weeks, months, or even years. Here, with tourists both in front and behind me, I felt pressured to just finish the damn hike. The rocks became overwhelming, and the only saving grace was the plants – especially the grasses, which were thriving in our late monsoon.

As the trail began descending a side canyon, I could hear a small waterfall hidden in the rocks below. Soon I came to a trickle of water, and finally, to a pool I could cross on boulders. The side canyon emptied into the main canyon and I came to a trail junction. My loop continued onto a traverse across the slope of the main canyon. This part of the loop was much less traveled – even overgrown in places – and here, I became fixated on the grasses.

Nearing the turnoff where the trail left the main canyon to climb back to the crest, a young couple caught up with me – the old cliche of a tiny girl with a huge guy to keep her safe. As they were passing, the boy asked “Have you seen anything cool?”

Surprised, I asked him to repeat, and when he did, I replied “Are you kidding? Everything here is cool!”

That got me started wondering what wasn’t cool – the stone stairs? The tourists? The fact that it’s a national monument?

Natives talk about the time when animals were people. Before humans, animals had to figure out how to live, by trial and error. Then when we came along, the animals became our mythical teachers.

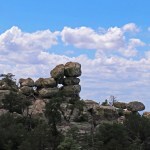

Long ago I came to realize that everything is alive. Everything has its own form of awareness, and the ability to interact with the rest of us.

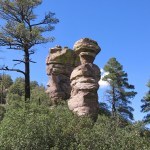

This place reinforces my notion of rocks as living beings, more than any place I can think of. It’s spectacular, but it can also feel a little spooky. As you recognize human features in the rocks, you realize we’re outnumbered here. Way outnumbered by this looming crowd. Barring some mutual apocalypse, they’ll be here, watching, long after we’re gone.

The lonely traverse up the main canyon, away from the stairs and the tourists, had somewhat lifted my bad spirits. Parts of the trail had reminded me of favorite rocky, shady spots on hikes in the Pinalenos, the Arizona White Mountains, the Mojave Desert, even taking me back to the Sierra Nevada of my youth. Lush, intimate pockets in a vast, monumental landscape.

September 7, 2025

Alcoves, Rock Outcrops, Nooks, and Crannies

Our weather’s getting cooler – at least for now – but it still wasn’t cool enough for low elevation hiking. And since my knee is still (hopefully) recovering, I needed a level hike – which are hard to find at cooler elevations. But to narrow my choices even more, I wanted a decent lunch spot somewhere along the way. I’d already done the northwestern option last Sunday, and the northeastern option offered a couple of untried lunch spots that didn’t excite me at all.

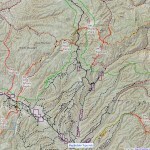

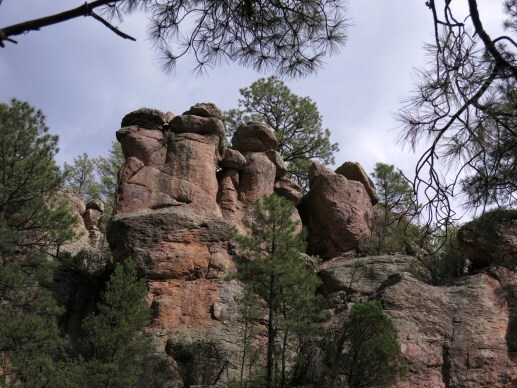

But looking at the map again, I realized the northeast route offered the possibility of a shady canyon hike at over 7,000 feet, accessed via one of our most iconic backcountry roads. The map shows a trail running less than a mile down the canyon, but I figured I could keep walking to get my mile in. The Forest Service has a web page for that trail mentioning “alcoves, rock outcrops, nooks, and crannies”, but all I was interested in was the elevation and shade.

Not a cloud in the sky as far as the eye could see. But I was encouraged to find the river running – and actually in moderate flood. Amazing that in town we can still be in severe drought, while only thirty miles east they’re having a sustained wet monsoon.

Leaving the highway and climbing to the mesa, I found abundant wildflowers and lush grassy slopes all around, and actually began to get excited about the coming hike, despite the boring sky. This road starts out well-graded gravel, but as it dips into canyons it gets rockier – and it’s popular, so you gotta watch those blind curves and be ready for big pickups going too fast and tourists going too slow.

I parked in the tiny campground in the dark, narrow canyon that had seen a lot of debris after past wildfires. I saw a couple other vehicles back in the trees, but no people. The campground track had once crossed the now-dry creek, but floods had made it undrivable. There was no trailhead so I just followed what was left of the vehicle track until it ended and I found a trail sign.

Taking flower photos slowed me down a lot. I came to a spot where the creek held a little water in bedrock, then reached a cairn where the trail began climbing. I checked my map and found this should be the spot where the canyon trail branches off. But there was no tread through the new growth of annuals, so I just started finding my way down the banks of the creek.

Within a hundred yards or so I found the barest vestige of a trail – maybe just a game trail. It soon petered out, but short stretches would reappear at random. No worries, I’m pretty good at find the best route, and I couldn’t go wrong in this narrow canyon.

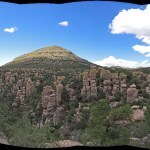

I saw some rock bluffs along the dry creek, and a formation on a slope above, but after a half hour I still hadn’t reached the “alcoves” etc.

Finally I saw something off through the trees that might be an alcove. And from there on, the slopes on both sides of the canyon became rockier and rockier, until I came to a narrows with an overhanging rock wall.

This is where the party began! I laughed, remembering how I had disregarded the name “Rocky Canyon”, thinking it would just offer mild temps. Little did I know it would turn out to be one of the most spectacular short hikes in our entire region.

Of course, the rocks were still mostly hidden behind trees, and up slopes that were a struggle in my knee brace. But even the canyon bottom was a beautiful, magical place.

No trail in this narrow, rock-walled stretch of canyon – I mostly stepped precariously from boulder to boulder in the creekbed, protecting my knee as best I could.

I’d spent more than an hour so far, on what was intended to be a one-mile out-hike, but I had to keep going until I ran out of rocks. In the end, it took me an hour and a half, and when I checked the map I found I’d hiked almost two miles and dropped over 400 vertical feet. No matter, I was in heaven – and the weather was perfect. I even had a breeze.

With less stops for photos, it only took me an hour to get back to the campground. Looking up, I spotted a few clouds through gaps in the canopy. The last remaining camper was just leaving, but others were arriving in a huge pickup.

Monsoon clouds were beginning to fill the sky as I drove up onto the mesa and headed back toward the highway. I had a late lunch at the less boring of the two untried spots – I was the only customer, not a good sign. But the huevos rancheros were actually pretty good, so I’ll be back.

September 1, 2025

Before the Flood

I invited my neighbor along for this short hike in one of our most spectacular canyons. We seem to be entering another active phase of our Southwest monsoon, and impressive clouds were spreading over the high mountains as we drove north. But the creek, normally running, was mostly dry.

I only went about a mile up canyon, and by the time I was halfway back the sky was pretty threatening. We both welcomed the rain, but this narrow stretch of canyon wouldn’t offer many escape routes during a flash flood.

The rain hit as we walked from the vehicle to the cafe for lunch, and continued steady all the way home – one of our best rains this season.

August 30, 2025

Rocks Above

This one’s for my mom. Just a stroll through a nearby canyon that’s normally one of our wettest places year-round, but is now bone dry, late in monsoon season.

August 25, 2025

Nature Walk

I needed another short, level hike to continue my knee rehab. There are several of those within a half hour of home, but after last week’s three-day getaway, I had returned to problems that were just getting more acute and less surmountable.

I discovered that my favorite backroads cafe had reopened, and after studying the trails, realized that a short “nature trail” in the canyon bottom would be perfect for my knee. When I’m in shape, I avoid these easy, dumbed-down hikes, but now…

So I headed across the border to Arizona again, for an escape and a decent lunch as much as for a hike. Our frustrating monsoon was in remission, only a few small clouds lurked on the horizon, and the afternoon high there was forecast to reach 90.

It got hot there in the canyon bottom, with the paved road, and tourist cars, sporadically visible through the trees, just across the creek. But I immediately began noticing tiny marker labels at the foot of trailside trees, and became obsessed with finding them all – so that I had to periodically force myself to back off and scan the habitat around me, and up to spy the looming rock formations.

On this hot day I was alone, until on the way back I encountered a knowledgeable young couple who confessed they’d become equally obsessed with the labels – and had noticed, as I had, that whereas labels identified yuccas, sotols, beargrasses, cholla cacti, and even grasses, none of the abundant agaves or prickly pears had been labeled.

In the trailside plants and labels, several aspects attracted my scrutiny.

First, I was both amused and delighted that in many cases, they’d chosen to label potentially hard-to-identify specimens like seedlings or plants that were damaged or mostly dead.

Next, I have a tree guide, and for years I’ve been struggling to identify the trees here, from the canyon bottom at 5,000 feet to the crest at almost 10,000 feet in elevation. So I was glad to see some of the harder-to-identify trees labeled via widely varying specimens.

And since I’ve barely scratched the surface of shrubs here, I was pleasantly surprised by labels on some of those.

Finally, especially after seeing the Apache pine, I began to wish they’d included Apache names for these…

August 22, 2025

Knee Trial in Paradise

My doctor had unlocked the knee-immobilizer brace three weeks ago, recommending I take it easy for a couple weeks, then start doing occasional short hikes. But I re-injured it somehow a week later and iced it for another week. And now, on this road trip, with one of my favorite trails nearby, I decided to finally try it out.

It’s hard to imagine a more beautiful hike anywhere. There are two routes to the peak, converging up neighboring canyons, with a “crossover” trail between them at bottom. I’ve been hiking parts of it for many years. Four years ago I finally did the full 18-mile loop, at the peak of a wet monsoon, finding a hallucinatory diversity of fungi. And two years ago I hiked the best part of it in snow, which if anything made it even more spectacular.

But today I could only do the first mile, and I was hoping that would get me to a view of the unique, iconic sandstone formations up on the ridge.

This is the most popular trail on the plateau, and even on a weekday the parking lot was nearly full. But everyone was spread out and I was alone almost all of the time. I did meet a man my age on the way back, starting a final hike before surgery.

Halfway in, the trail leaves the tiny river and begins climbing. To protect my knee, I followed an informal trail that led directly up the valley toward the interior meadows. It was these meadows that finally freed my mind of the anxiety that had driven me here. I was at peace, just looking and breathing, if only temporarily.

Gone Fishin’

When my dad died 16 years ago, I actually kept his backpacking rod and small tackle box with a decent spinning reel, but I haven’t fished since I was in high school. And most of that was with Grandpa, in Midwestern rivers and ponds, for small fish like perch and bluegill that Grandma fried at home. I still prefer inland freshwater fish like that over any kind of seafood or anadromous fish.

But this week I was heading to a fishing-centric retreat in search of something more elusive – recovery from stress I simply couldn’t handle at home.

The drive north was an adventure in itself, through a couple of cloudbursts in some of my favorite country.

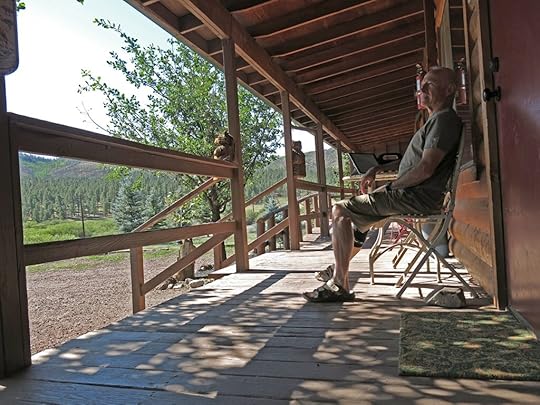

I’ve been visiting this remote mountain resort for fifteen years, first discovering it on a ski trip to the nearby slopes run by Apaches. It’s a narrow valley carved by a tiny Western river out of a volcanic plateau. The plateau was discovered early by cattle ranchers, and the surrounding forests by loggers. The valley, which extends only about three miles before dead-ending, lies at 8,300 feet, stays cool all summer, and has become a popular hot-weather retreat for folks from Phoenix and Tucson.

There are bed-and-breakfasts and scores of cabins for rent, but I stay in the only motel, with eight small rooms with varying numbers of beds and an attached convenience store – the only one in the valley.

Gas, groceries, and other necessities can be found in predominantly Mormon towns up to a half hour away, but the valley has a legendary historic restaurant, an excellent cafe for breakfast and lunch, and other options which come and go. I especially like the quaint museum honoring an early Native American painter and his family.

It’s a resort, and lots of palatial vacation homes are hidden in the forest above the valley, but it retains a modest family orientation, rooms and cabins are affordable, and I’ve always felt welcome there. One of the main draws, apart from trout fishing, is the nightly ritual of elk – a large herd – coming out to feed in the roadside meadows. And there are often Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep grazing along the highway into the valley.

The plateau, averaging 9,000 feet in elevation, extends about 20 miles east to west and about 30 miles north to south, and the northern two-thirds of it consists of gently rolling grassy meadows punctuated by low forested ridges and clear lakes.

At its western edge, the plateau rises to its highest point, a sprawling 11,400 foot mountain lined with spruce-fir-aspen forest that spawns three major rivers. On the morning of my first day, I headed there from the valley on a dirt forest road.

From the foot of the mountain, the southbound road curves east into the meadows. The grassy meadows covering the rest of the plateau extend farther than the eye can see, and hence seem to be endless. Others have suggested that country like this is common farther north, in Colorado or even Utah, but I’ve never seen or heard of a plateau that sits like a table in the sky like this, without a wall of mountains to contain it. And here, it rises directly from the southern desert.

At the center of the plateau, I turned off on another road that heads to the northern rim.

And once back on the east-west highway that skirts the northern edge of the plateau, I decided to check out a trailhead I’d used once, on a fork of the river. It turned out that a wildfire in May had damaged the trailhead and campground and the road was closed.

On my second day, I did an experimental hike – the first with my recently-unlocked knee brace. And on the third morning, I headed home – back into the nightmare.

August 20, 2025

Alone in the World

here I am again

trying to escape my unbearable life

even here, high in the mountains, far from towns, far from home, hard to shrug off the pressure, the need to be obeying my schedule, my obligations, getting things done, solving problems every damn minute

at sunset last night the elk came out into the roadside meadow, between fifty and a hundred, cows nursing calves

my mind absent with stress, i left my car lights on during dinner, came out in the dark to a dead battery, a little over a mile from my room and a couple hours from the nearest AAA service

i called them and sat in the car waiting for an hour, went back in the restaurant to pee, had to explain to the servers, the cook came out and jumped my battery, got me started

it’s morning, i’m on the veranda in the sun

sky clear, air warming to mid-70s by afternoon

watching the road, people visiting their vacation homes, contractors resupplying or renovating

want to drive across the alpine plateau, never get tired of that endless dreamlike landscape, meadows and lakes and volcanic ridges, but if i wait till afternoon monsoon clouds will come to complete it

brought my guitar, working on a song about a visit with a sometime girlfriend 34 years ago

beautiful, talented young woman struggling with mental illness, to whom i brought an abundance of patience and gentleness but no relevant experience or skills

how as an adult from a severely dysfunctional family she was alone in the world, society demanding she follow the rules, stand on her own two feet

and she tried, again and again, to fulfill society’s expectations, to conform to the patterns of career, home, relationships, consumerism and the market economy, while randomly but continuously derailed by terrifying hallucinations and the impaired judgement and faulty decisions that resulted and regularly misled her

under that relentless pressure from this fundamentally suicidal and homicidal society, afraid of being locked up in an institution, she believed she had been given all the resources she needed to succeed, and when she sought treatment, it was for the symptoms, not the illness

and we think if we could just elect the right president, solve climate change, and allow trans people to serve in the military, we could get back to normal

as i listen to the radio at home every day i note music that surprises me, and after the list nears a couple dozen I review them and download the ones that still surprise me

did that before leaving on this trip, and the result is probably the best playlist I’ve ever put together, ranging from John Mayall (1960s) to Arthur Russell (1980s) to obscure, short-lived British and American indie projects from the past 20 years, women with angelic voices, men who sound like pipe organs, Ethiopian jazz, and “world music” collaborations

so it’s on continuous shuffle on the boombox beside me on the veranda here

and because i can’t just sit and do nothing, i’m writing this Dispatch

and yes, wishing you were here

August 10, 2025

Rocky Road in the Sky

Our heat wave was forecast to taper off in a few days, with the monsoon clouds returning. And doc says I can start doing short hikes, also in a few days.

But meanwhile, I needed a Sunday road trip, and the area that intrigued me the most is low elevation and was likely to be pushing 100 degrees.

I studied the maps over and over, and finally realized that at the west end of that area, there’s a 6,500 foot peak with a road traversing it. I’d never considered exploring it because the top is covered with communications towers, and I hate towers on mountaintops. But it’s also surrounded by spectacular desert terrain and other mountains and buttes with colorful rocks, and the vegetation around there is a delightful mix of Sonoran and Mojave genera, so why not give it a shot?

After crossing the mountains south of town, I discovered the vast southern plains were blanketed with a mysterious, low-lying haze. It wasn’t windy, so I wondered if it might be humidity.

Then when I turned north, I was surprised to see some monsoon activity far ahead. I drove through the Mormon farming village, crossed our iconic river (muddy and barely visible amid its broad, dense canopy), and enjoyed an interval of rain before reaching the alluvial mesas and the turnoff for the “backcountry byway”.

Backcountry byways are dirt and gravel roads graded and maintained for recreation on BLM land. The map shows that this one crosses the iconic river, way the hell in the middle of nowhere as it makes its big bend west, so that was something else to look forward to.

The monsoon clouds spreading from the north were intermittently cooling off the air, enhancing the landscape, and making photography a challenge in their shadows. I had a great view of the mountain with the towers, which I’d never identified before.

After less than a mile on the byway, I pulled over to deflate my tires. Regular cars use this road, but regular cars have soft suspensions.

At the river, I could hear folks making noise down in the picnic area, but couldn’t see them for the trees. Despite the humongous copper mine to the north, this landscape is pretty miraculous, with a legendary river hidden in a narrow canyon in the midst of harsh and colorful desert.

Past the river, the road gets rougher and cuts back into a long valley toward the foot of the mountain. I came upon a big late-model pickup driving less than 10 mph on a straight, wide, recently-graded stretch. I followed them for almost a mile as they continued to drive in the middle of the road, blocking me. Finally we came to a wide enough spot I could squeeze past them.

And at the head of the valley, the road gets narrower and begins climbing the shoulder of a long outlying ridge.

When the road crested the shoulder, I stopped to check my map, and discovered that the road to the summit starts here. Communications tower access roads are notoriously poorly maintained, and I had to shift into low range 4wd just to get up the turnoff.

This road, accessing the summit from the northwest, climbs over a thousand feet in two miles, so the views northeast are pretty spectacular. But it’s also very narrow, rocky, and steep, so I had to pay close attention. There are no wide spots, so I kept wondering what I would do if I encountered another vehicle.

I considered that unlikely, but just as I came to the only wide spot before the crest, I saw a side-by-side heading down toward me. What are the chances? And what would we have done if we’d encountered each other a few minutes earlier or later?

Fortunately, they said there was no one behind them.

When I reached the crest, I got a view to the southwest. But the road became even rougher. I began to realize this was probably the gnarliest road I’d ever driven – but after driving that road to the crest of our eastern range a couple weeks ago, I was fairly calm. Guess I’m getting used to this.

I stopped in the saddle below the summit, at nearly 6,400 feet. The temperature was perfect, with a little breeze, and I had a snack – with many stops for photos, it’d taken me almost an hour to drive the two miles, and I was very late for lunch.

Here, as on the lower slopes, I found widespread tree mortality, presumably from our long, severe drought. But I also saw some happy seedlings of both pinyon pine and juniper, so all is not lost. And cliff swallows constantly swooped past me.

I had no interest in driving to the top, with its forest of towers, and this narrow, rocky ridge was no place to linger.

The road south brought me into the head of a canyon which was very dark under the spreading thunderhead. I’d wondered if the southeast road might be better than the northwest one, but now I discovered it’s much worse – lined with sharp rocks, ledges, and deep ruts. But after a few rains, it’s also lined with very pretty flowers.

It traverses down another long ridge, and from what I could see of the next stretch of road far below, it seemed like an easier surface.

My view from above turned out to be an illusion. This descent was lined with volcanic cobbles literally from top to bottom. In the past I would’ve been a nervous wreck, but the flowers were so good I took it all in stride.

It had taken me two hours to drive five miles. This end of the road connects with an unlikely highway, a high-speed thoroughfare in the middle of nowhere that connects the giant mine with the city that supplies it, far away in the big river valley. That was my route back to the farming village, where I slowly carved my way through a very late lunch of lemonade, chips and salsa, and red enchiladas.

And after that, an hour-long drive home – discovering on the approach to our southern mountains that the haze was indeed due to wind. A wind so strong it slowed me down on the plain and tried to push me off the highway in the mountains. But those clouds had really cooled off our heat wave!