Max Carmichael's Blog, page 6

October 14, 2024

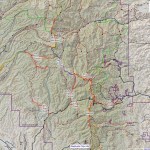

High Color

This marks the hopeful return of my hiking Dispatches, after a three-month hiatus due to knee pain and family troubles. In August, I got an injection for shoulder pain, and the dosage was so high it gradually wiped out pain in both shoulders and the knee, but in September and October, travel prevented me from walking or doing rehab. The long rest seems to have finally eliminated my knee pain – knock on wood! But on my first short walk around town last week, I got bad shin splints – is this old body ready to curl up and die after all?

I was really missing the high mountains, so I decided to make another long, arduous drive for a short hike. We’re having apocalyptically warm weather this fall, and the high in town was forecast in the low 80s, but that would mean 70s in the mountains – perfect.

Since my first journey to the northern edge of our wilderness, four months ago, monsoon rains had torn up the steep, winding, one-lane forest road over the 9,000-foot crest, cutting deep gullies and exposing more embedded rock. Driving it now was like driving over a debris field. As long as I wore my noise-cancelling headphones I could just bounce my little truck over the rocks, although with no weight in the bed there was a lot of wheelspin. But on the last stretch I frequently had to pull over for bigger vehicles, took off the headphones, and the rattling left me a nervous wreck by the time I descended to the open country on the east side.

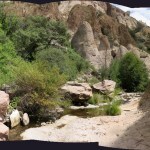

I picked this remote hike because I needed to protect both the recent shin splints and the long-term knee issue, and this is one of the few pretty hikes in our area that doesn’t involve big elevation changes. I wasn’t thinking of the fall color, but that turned out to be a bonus. We’re at the tail end of a severe drought, so I was surprised to see all the creeks still running.

There are a few small ups and downs to bypass creekside bluffs, and I took short steps or sidestepped down those to protect my legs, so it was a very slow hike.

All in all, it took me almost two hours to hike less than three miles on a very easy trail – but after such a long hiatus this is how careful I need to be.

It’s amazing how noise-dependent my stress level is. The headphones made the rough drive back over the crest tolerable, despite the traffic. For almost the whole distance, I ended up stuck behind a family in a big crew-cab truck. They were sightseeing, never exceeding about 7 mph, the kids hanging out the side windows, yelling at each other and tearing branches off roadside aspens.

My next goal was the tiny restaurant in the ghost town at 6,600 feet. They’re only open on weekends, spring through fall, because the road closes in winter. Basically a burger place, they have counter service inside with tables outside beside the creek, which has been channelized for flood control. It was a perfect chance to chill after the arduous road over the crest and before the final dangerous one-lane descent to the highway.

Despite not being able to do big hikes, trips like this refresh my soul. Spending my days in flat lands, in airports and airplanes, in city traffic – that just destroys me. Friends keep advising me on how to take better care of myself on these trips, but I’m actually the expert on that now, and it still doesn’t help. I simply waste away when I’m deprived of access to mountain wilderness.

September 9, 2024

High Lonesome Ranch

With weather cooling off, I could target lower elevations in my “no hiking” weekend road trips: drive somewhere interesting, explore a little, have lunch, drive home. This time it would be a remote, quiet, hardscrabble village at the edge of a Mormon farming community, at the foot of mountains I’d like to hike.

Lunch was red enchiladas, smiling and chatting with the local country folks. On the way back, I hoped to check out access to the east side of a wilderness area I’d explored from the south last winter.

Back then, I’d hiked across open range between two cattle herds and up a steep canyon between sheer cliffs, into a white-out blizzard of sleet at the top. And on the way back I’d been threatened by a bull and two ranch dogs. The storm had prevented me getting deeper into the wilderness, which encompasses most of this northern section of this extremely long and narrow range. But this section is so rocky and beautiful, I wasn’t giving up. After studying maps, I was hoping to find a less risky approach from the east, but I knew I’d be crossing more ranchland and had no idea if the roads would be open.

Also, I was driving my low-clearance 2wd pickup and had no idea how bad the roads would get. It’s a long approach on graded gravel, past an uninhabited backcountry railroad crossing, then more miles on an ungraded dirt and rock road that gets progressively rougher and less traveled, often detouring around washouts. I passed a spread-out herd and lots of what I assumed were feed dispensers, but didn’t see another human or moving vehicle. These flats looked terribly overgrazed.

The map showed two roads leading to the wilderness boundary at the foot of the mountains, one branching off from the other. I continued straight without ever seeing the branch, the road getting rockier, showing only one clear tire track. Eventually I reached a No Trespassing sign. There was no gate, and I see could see the road ahead cresting a rise, so I continued to the rise to see what was beyond.

From the rise I saw a metal roof down in a hollow, and couldn’t tell if it was a shack or a shed, so I turned back. A rural landowner myself, I have great respect for No Trespassing signs, but this sure was a beautiful place with the cliffs rising all around.

Some research back home revealed that this was where Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O’Connor grew up. At over 160 square miles, it supports 2,500 mother cows with 3-4 full-time cowboys, none of whom I saw.

On the way back, looking for the branch road turnoff, I stopped to watch a dust devil cross the road ahead. I assume overgrazing encourages their formation.

https://maxcarmichael.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Dust-Devil.mp4I found the turnoff in a big cleared area with more feed dispensers. After driving through a deep gully I reached a primitive gate. There was no sign here, so I continued, closing the gate behind me.

This even less-traveled road led back into a beautiful box canyon on the north side of the crest I’d hiked last winter. It dead ended at a stock dam, windmill, and water tank at the foot of the mountains, with a huge bull and a cow lounging a dozen yards apart – an odd couple to find isolated and alone like this.

God, what a beautiful place! I figured once I got my knee working again, I could probably find a way around the bull.

To someone familiar with this country, the vegetation is markedly different over here. This area is 2,000 feet lower than my home, and significantly drier, and on the way back I wondered how different it was before the introduction of cattle. I hope I can figure out a way past the bulls and dogs in the future!

August 26, 2024

Postcard Canyon

Our weather had cooled off – town was only forecast to reach 84. I still wanted to get away to someplace cooler, but now had more options nearer home than where I’d gone last Sunday. The county seat north of us was only forecast to reach 78, and there’s a fairly level hike on the way there that should be easy on my knee, and a couple of cafes for lunch afterward.

This is a canyon hike that was recommended within the first couple of months after I moved here, but for various reasons I’d never explored it. The trail begins at the end of a long gravel road with multiple creek crossings, and before I got my 4wd Sidekick, I was paranoid about my truck getting stuck. Then when I started doing long day hikes, I saw that being a canyon hike, this trail offered very little elevation gain, so it didn’t interest me.

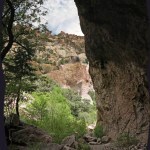

But I’d been told the canyon was spectacular, and I’d seen photos to confirm it. So knee pain now gave me an excuse to hike it.

The trail goes up the floodplain about 300 yards before entering the narrows. First thing I saw was a big rattlesnake – almost four feet long. It just moved off the trail without rattling.

The sky was partly cloudy, with a lot of deep shadows in the narrow canyon, so I had a struggle taking photos. It was beautiful, as expected, but muggy, and more than 400 feet lower than home. I’d gotten a late start and it was hot there.

Eventually I emerged from the canopy onto a dramatic stretch of exposed bedrock. Trying to protect my knee, and worried about the cafes closing at 2pm, I stopped where the canyon widened out. It’d taken me 45 minutes, but with a lot of stops figured I’d gone less than a mile.

On the way back, I spotted a school of trout, up to a foot long, in a pool below a cascade. It’s definitely a beautiful place, and there’s supposed to be another “narrows” further up, but it’s not really a hiking trail – it’s more for people who like to walk a short distance, without much effort, and hang out enjoying scenery.

By the time I got to the town with the cafes, it was after 2, and the better one was closed. Fortunately the other, a “greasy spoon”, was open, and I got a decent burger with the worst fries I’ve ever seen. A big storm was gathering and I decided to grab provisions at the market and check into the motel.

I’d passed the modest county fairgrounds on the way in, and in the motel office saw a poster for the fair – which was ending today. This is the biggest county in the state but has a population less than 3,600, with only 289 in the town. It’s the national center of the rural pro-Trump, anti-government movement, but I’ve always found the people friendly, I’ve never felt threatened or even uncomfortable here, and the surrounding habitat is wilder and better protected than most places I know in California. There are a lot of trails nearby that intrigue me so I keep feeling drawn to this area.

After I was settled into my room, I glanced out the window and saw a teenage girl feeding her horse outside the office. This is that kind of place. An hour later it was raining. My knee was sore again and despite getting a shot week before last, I still had residual pain from my right shoulder.

Early next morning, I woke up refreshed and hit the road south. A half hour later I found myself stuck behind an interesting outfit – a tall box truck with side windows in the box, towing what appeared to be a fairly large hand-made wooden boat. I patiently waited a few miles for a long enough straight stretch to pass.

August 23, 2024

The Agony and Ecstasy of Songwriting

This Dispatch is going to be a deep dive into the creative process. I know most of you are music lovers and hope you find it interesting – raw and unfiltered from the horse’s mouth instead of highly processed in movies like Once or the upcoming A Complete Unknown.

The last time I wrote new songs was over a decade ago – and those were just experiments, nothing memorable. After that, I became concerned about the hundreds of hours of archival recordings I’d accumulated with bands and friends, and began editing and releasing some of those. Meanwhile I was writing my epic novel and starting on a big painting. It wasn’t until early 2020 that I got the itch to write new songs. Maybe reviewing those archival tapes had reminded me of the era in which I matured as a musician – the post-punk years of 1978-1980 – because it finally hit me that although that’s what got me started, I’d only written a few true post-punk songs, instead plunging straight into primarily instrumental experimentation with my band, Terra Incognita.

But by 2020, I found myself listening to bands that carried the classic post-punk sound into the Eighties and beyond: Psychedelic Furs, Public Image Limited, New Order, The Cure, The Durutti Column, The The, Cocteau Twins, The Go-Betweens, The Smiths, Lowlife, The Railway Children. Some of those bands I’d heard of in the Eighties, but dismissed as I became obsessed with African music, so now I was discovering and falling in love with them for the first time, more than thirty years late.

However, I felt that the purest form of that original post-punk sound had been achieved by New Order immediately after Ian Curtis’s suicide, in their 1981 recordings of “Ceremony” and “Dreams Never End”. But rather than developing it further, they abandoned it in favor of club dance music.

More than the snarl of John Lydon or the slashing guitars of Delta 5 and Gang of Four, New Order’s use of clean tones fattened with the chorus effect, with the guitar playing rhythm and the bass playing melody, seemed to symbolize the revolutionary nature of post-punk. To me, it was more of a breakthrough than Sixties rock, because Sixties rock was primarily blues-based, and post-punk had nothing to do with Black music. This is important because academics tend to dismiss all rock music as a ripoff of the blues. The roots of post-punk are hard to trace, but to me it evokes traditional Gaelic styles like pipe band music transposed to a rock format – bands like Big Country and New Model Army made that transparent later in the Eighties.

Anyway, New Order’s abandonment of their origins made me want to write songs in that style, and in early 2020 I recorded some instrumental tracks to my favorite post-punk beats and did some vocal improv over them. Then the pandemic took over, my house caught fire, and the next two years were spent trying to recover. During that hiatus, I discovered that the goth subculture, inspired by Joy Division and The Cure, had actually rescued that early sound and perpetuated it worldwide in a series of obscure bands that continue to this day.

Through pain, illness, trauma, and the stressful work of helping my family, I kept getting ideas and making notes about the new songs I wanted to write. In my heart, I really just wanted to write classic post-punk songs, but I’d spent decades studying and experimenting with African genres – especially my favorite, Nigerian Yoruba apala music. And as I reviewed and analyzed my work since 1980, I realized that my forté as a songwriter and composer is to invent new sounds by fusing distant, unrelated traditions – like I did with Nigerian juju and Appalachian in the Eighties, and apala and Native American in the Nineties. Could I fuse apala with post-punk or goth?

From the HeartOccupied with family duties, I literally didn’t have time for music until I was forced to make time in April of this year, setting Katie’s songs to music for her ceremony. That, and the ceremonial handover of African drums from a colleague, a few months later, have provided the impetus for my new songwriting effort.

Turning Katie’s lyrics into songs proved to be easy, and I began wondering if the pain and trauma would end up making me a better songwriter and singer – that’s the old cliche. Singing lyrics that poor lost Katie had addressed directly to me definitely got my heart into my voice. Here’s the latest, a true story from the beginning of our relationship:

https://maxcarmichael.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/ChapelofLove.mp3After finishing a series of Katie’s songs, I sat down and organized my notes, which included dozens of potential themes or ideas for songs. But of all those songwriting notes I’d accumulated since 2020, the most urgent was to “write from your heart”. In the past, the work of inventing new genres had allowed my brain to dominate. I’d written songs about things that inspired me in nature and prehistory, but by the time I finished the songs I’d ironed most of my feelings out of them.

More recently, when I wrote lyrics and tried singing them over instrumental tracks, they always came out as either too cerebral or as plaintive, mystical garbage, which is a rut I used to get in when smoking pot.

Making it even harder, in addition to evoking strong feelings in my songs, I was still determined to work outside existing genres, making everything up as I go along, combining instruments, rhythms, melodies, and harmonies from exotic and obscure traditions, while showing my love of nature and indigenous cultures and embodying the questions I’ve pursued and the lessons I’ve learned from an adventurous life. I always need a challenge.

Clear Creek Canyon GirlFortunately, there was one subject that was still fresh in my heart – an encounter with the past in Indian country, in which I fell in love with someone who was about as inaccessible as you could get. I decided to start with that.

I started out by writing the story of my impossible love in the form of rhythmic lines, but when I tried various ways of setting those lines to music – with African drums, drum kit sounds, a bass line, or guitar chords – by the end of the day I was back in the same old boring rut.

So I studied my music library for inspirations – beats or structures I could adapt. Maybe I could use other peoples’ songs as disruptors to prevent me from falling into past ruts.

I started with PJ Harvey’s “The Wheel”. I spent another day using that as a touchstone – and I do love the song – but it turned out to be totally the wrong feel for my story.

So on the third day I turned to New Order’s “Love Vigilantes”. I like the song, and I love the power and simplicity of New Order’s rhythm tracks, but mainly I had the idea that the story resonated with mine in some nonintuitive way. To make things easier on myself, I settled on drum kit sounds as a placeholder, hoping to work the African drums in later. The “Love Vigilantes” approach worked, but you’d be hard-pressed to recognize the inspiration in the final result!

Each time I started over, I deleted six or eight hours of previous hard work, which takes motivation and discipline. On all three days, I was in pain and taking meds, and the meds pushed the pain into the background enough for me to work. I had to get my heart and mind to work together somehow – fiendishly tricky.

I finished it on that third day, and the result literally had me in tears. Maybe it wasn’t just the tragic love story – maybe those years of pain and trauma had something to do with it. In any event, the joy I feel after an accomplishment like this is better than anything else in life.

And the song was long – almost six minutes! Afterward, I happened to hear Gordon Lightfoot’s “Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” on the radio. A six-minute tragic folk ballad, it reached the top of the pop music charts in 1976. Can you imagine something like that competing with Taylor Swift today?

I can’t share my new song with you until it’s ready for legal distribution – weeks of further work – but here’s a snippet of “Clear Creek Canyon Girl”:

https://maxcarmichael.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Clear-Creek-Canyon-Girl-snippet.mp3Stranger to the World

After that success, I was really stoked, but it still wasn’t Afro-Goth. I didn’t know what it was, it seemed a one-off like many of my compositions. So for the next song I went for broke and took New Order’s “Dreams Never End” as my inspiration – a track that’s sacred to me. The subject would be my childhood pastor, who set me on a life path as a seeker. I wanted to honor him while showing how hard a path it is.

I started writing lines based on the phrasing of “Dreams Never End”, but as I might’ve expected, I soon lost control of the subject. What was it about? My long-lost pastor, or my entire life story? How could I narrow it down and turn it into something that might engage an unfamiliar listener?

I recorded a rhythm track roughly inspired by DNE, using software drum kit sounds, and tried singing some of the lines I’d written over it, finding a key that seemed to work with my voice, and a chord progression I could alternate repeatedly. But the lines I’d written were woefully incomplete, so I spent the next two weeks trying to outline the song and focus the theme, in between doing rehab exercises and struggling with the side effects – insomnia, hot flashes, splitting headaches – from a shot of prednisone a doctor had given me for pain. This, after finishing the first song in three days! This is my kind of art, moments of ecstasy separated by days of agony.

But after seven or eight drafts I finally got something that was enigmatic but heartfelt, triggering tears again by the time I reached the end. I’d recorded an acoustic guitar track to sing over, and now I added bass and electric guitar, still trying for that post-punk sound.

But now, it had so many echoes of the New Order song, I realized I had to make big changes to avoid a copyright issue. I slowed the tempo way down, and that actually allowed me to put more feeling into my vocals. Then I realized the tempo was similar to one of my favorite apala songs, so I recorded syncopated talking drum tracks using big and little drums. In the past I’ve used banjo to take the place of lamellophone (mbira, thumb piano) in apala, so I tried a banjo track. But that made it sound way too folky, so I tried the same part on bass, and the song really began to work.

I muted the original drum kit tracks – the song seemed to be working with just talking drums, electric bass, and electric guitar. But now that I was closing in on it, I discovered I didn’t really have an ending – I just had a series of verses, all with the same phrasing. The last set of lines could be used as an ending, but I wanted them to have a different chord progression and melody, something climactic. I remembered a brief passage in a song that’s been playing on an LA radio station I listen to daily, a song by an obscure indie-pop band from the early Nineties. An achingly beautiful melody with a seven-chord progression that occurs once in the middle of the song.

I fit that to the existing key of my song and recorded a track with the guitar chords at the end. Singing over them in that melody took my voice a little too high for comfort, and totally changed the character of the song, but I decided to keep it for now. Now, the song seemed too powerful for just the talking drums, so I tried adding the kit drum sounds back in, and voila! Afro-Goth!

After listening to it from the beginning, I realized the main melody was just too close to New Order’s. I mean, the beat was now completely different, none of the instrumental parts were similar, but I’d succeeded in singing too much like Peter Hook. So I experimented to see if I could “apalafy” the vocal melody, using melismatic singing. That actually worked, in that I ended up loosening and putting soul into what had previously been a bleak, metronomic performance.

But the ending still bothered me, and my heart sank when I listened to the full song on my big speakers, and the new ending melody suddenly reminded me of a famous, sappy old pop song, probably by Barry Manilow.

What could I possibly do after investing this much time and work? The answer turned out to be simple. I ignored the high-pitched melody from the indie-pop song and sang my final lines in a lower register over the same chord progression, to a melody I just made up. At first I sounded a little like Elvis doing a gospel standard, but that inspired me to put even more soul into it. It ended up subtly evoking early rhythm & blues.

I’m sure I’ll work on it more at some point, but for now I’ll consider it done and start on something new.

Here’s a snippet of “Stranger to the World”. Can you hear the talking drums? Does it remind you of “Dreams Never End”?

https://maxcarmichael.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Stranger-to-the-World-snippet.mp3

August 19, 2024

In Search of the Cool

Now that I’ve embarked on a new, hopefully temporary Sunday routine of one-day road trips, I’m starting to get more analytical and organized – another aspect of my lifelong struggle between left and right brains. But the problem with remote destinations in this remote region – even after decades of internet, web, GPS, smart phones, apps, and social media – is that reliable information is often lacking. And when no one answers the phone or nothing shows up on Google Maps, you have to actually drive a couple of hours to find out if something exists or is open. I find that refreshing and hope it’s never completely “fixed” by the techno-utopians.

I’d been suffering through so much heat at home that I wanted to escape to the Arizona alpine plateau, which would be 15 degrees cooler – in the 70s. Driving north past the big ranches west of town, I approached a pair of bikers weaving constantly back and forth in opposition to each other. They pulled over and stopped as I got close. Their bikes were new and futuristic, stark black and white, as were their outfits – they reminded me of the Apple or Elon Musk aesthetic. But a little farther up the road I saw them in my rearview and they passed me, and began weaving their bikes theatrically back and forth in opposition again. And then, a few miles farther, I passed them again, stopped on the shoulder, gesticulating at each other. More weird city people invading our rural refuge.

The route crosses a series of intermediate passes, and approaching the highest, at 8,000 feet, I remembered there was a forest road heading north along a long ridge that overlooked the canyons and basin to the east. For once, I wasn’t on a schedule and decided to check it out.

It was pretty well graded and led through mature ponderosa pine forest dappled with sunlight and shade. I wasn’t planning to go very far, and I hadn’t seen anything interesting yet, when after a little more than a mile I saw sky through the trees to my right, and wondered if that was the rim of the ridge. Shortly after that I came to a dirt track leading off in that direction.

Winding beneath the big trees, it took me to a campsite on the edge of a rock cliff overlooking a broad thousand-foot-deep canyon toward the distant skyline of our 11,000 foot mountains thirty miles away. It was the most spectacular campsite/picnic spot I’d ever found in my home region. It was litter-free and someone had left a little stack of firewood. I even found a young Arizona cypress growing on the rim, a tree I’d never seen in this area.

From there I drove to the Arizona hamlet at 8,000 feet, a two-hour drive from home, where I was hoping to get lunch. But the grill was closed – once again, no definitive info online – so I decided to drive higher onto the volcanic plateau, another half hour of driving across one of my favorite wild, uninhabited landscapes, to an isolated lodge that I knew was open daily.

The drive winds through burn scars and intact spruce-fir forest, climbing over ridges and into and out of side canyons, passing the broad grassy meadows that line much of this plateau. At an elevation of over 9,000 feet, I came upon the lodge suddenly and pulled off. There were two motorcycles parked in front.

I found the restaurant door unlocked and went in. Two retired-looking biker couples stood examining a map on my left, and a sign said to seat yourself, so I took a seat at the counter until one of the men came over and told me the restaurant didn’t open until noon. I went outside to wait at a table, and the bikers rode off.

I needed to pee, and hadn’t seen restrooms in the restaurant, so I entered the main door of the lodge. The reception counter was unoccupied, but a very old man slumped on a sofa opposite, staring at something in his lap – probably a phone. I peered into the office and up the stairs, then turned and asked the man if there was anyone working today. I was standing less than six feet away, but he ignored me.

“Excuse me, sir,” I said. Then he slowly looked up with an angry glare. Even more slowly, he took a tiny device out of his ear and shook his head in apparent disgust.

“Did you say something?” he snapped.

“Sorry to bother you,” I replied. “It’s nothing.” He put the device back in and looked back down without another word.

I went back outside and tried the restaurant door. It had been locked.

At my table on the front deck, a constant swarm of hummingbirds surrounded a feeder behind my left shoulder. It’s an incredibly beautiful spot, and the weather was perfect. I watched a thunderhead develop across the highway, behind the spruce forest, far to the west. A four-door Jeep arrived with two more retired couples. After I told them about opening time, they wandered off to examine the property. A half hour later an older couple arrived, and likewise wandered off.

This place is known in both the Phoenix and Tucson metro areas. It’s a long, arduous drive, but that’s what bikers seem to crave, and summer in those urban hellholes makes people desperate for relief. And this is paradise compared to the crowds and traffic of closer getaways like Sedona and Flagstaff.

Nearing noon the two couples returned and asked me what I knew about this place – I’d spent the night here once and had dinner. Then the restaurant door was unlocked and our small group filed in.

I had a burger that appeared to be nothing special but tasted unusually good. I overheard the couples telling the waiter they were from Yuma but were spending the summer in Show Low – an interesting life plan. I wondered if they were staying in personal RVs or vacation homes. Yuma houses a legendary prison and is notorious for being the hottest town in the U.S., with an average summer high of 115. I’ve heard it called the armpit of the Southwest. I wondered how anyone would choose Yuma as a retirement destination. But if they did, why would they need to choose a summer home in the same state? Tax reasons?

And then consider the options – towns that would offer a summer refuge. My first choice would be the casual resort village across the plateau at 8,400 feet, but it’s very expensive. Show Low is basically a bustling redneck town, only slightly higher in elevation than my hometown, center of a big ranching district – no way would I consider it a pleasant summer retreat. These folks intrigued me.

We finished at roughly the same time and exchanged a few words at the door. I mentioned I’d overheard they were from Yuma, and said I knew it by reputation, having only passed through. One of the women said “We live there, we’re not from there! We’re from New York state.” Apparently I’d touched a raw nerve, and the mystery deepened.

Driving off, I made it only a few miles down the road when I approached a trailhead and decided to check it out. I’m not hiking, but I really wanted to immerse myself in this beautiful forest with its crystal-clear, high-elevation air.

Unsurprisingly, only a few yards up the trail my legs took over, and I realized my body was desperate to walk. I simply couldn’t avoid exploring farther. A storm had come over and raindrops were falling so I grabbed my shell out of the pickup.

The trail climbed steadily, 300 feet in elevation to the top of the ridge, and unfortunately this patch of forest had been touched by the massive 2011 fire – not at high intensity, but enough to thin it out, creating a maze of deadfall and near-continuous thickets of locust regrowth. One treat was the strawberries – I’d never seen so many, although they were small, and most were not ripe yet.

Light rain fell on and off. I was hoping to get across the ridge with a view into the big river valley to the east, but this turned out to be part of a broad network of ridges and canyons. After three quarters of a mile I turned back – my first, very short, hike in almost a month!

On the way back, I was reviewing my interactions with the folks at the lodge – I’d also had a brief conversation with the other couple. Apart from the occasional angry old man, most interactions with strangers in isolated, lonely places like this are much friendlier than you’d have in crowds or in town. People tend to be excited to meet strangers and discover secrets of their lives. As a result, you briefly get a more optimistic and tolerant view of humanity, which is paradoxical for someone like me who values solitude and is generally considered a cynic. But like all pleasures, it’s fleeting.

August 12, 2024

The Shape of Things to Come

Three weeks with no hiking Dispatches! I hope that’s given some of you a chance to catch up?

The big news is that I’m writing songs. The last time I had a sustained burst of songwriting was thirty years ago – that’s why this is big news for me. Life got in the way, but I can already tell it was worth the wait. More on that in the next Dispatch.

A lot still stands in the way. I have more pain than ever, it’s out of control, disrupting my sleep, requiring too many meds. After working indoors all week, my body and soul need wilderness hikes on the weekend, but those are no longer possible due to a knee problem – with a two-month waiting list for treatment. Not only does my body require more maintenance than ever, but also my fire-damaged house, my overgrown yard, my dilapidated vehicles – especially in monsoon season with weeds exploding, animal pests invading, heat that requires hands-on management throughout the day due to a lack of effective insulation and cooling. And alongside all that I’m constantly managing my family situation back in Indiana, solving daily and weekly crises remotely, forced to make decisions for all of us, usually alone.

As painful as it may be for me, the inability to hike or do creative work is a first-world problem. What we call “the arts” have roots in traditional, indigenous ways of life, but our versions of these arts are so far removed, so decadent, that most of them have no place in a healthy, sustainable culture. A subsistence culture has no use for oil paintings, literary fiction, violin concertos, opera, or ballet. Songwriting, painting, and literary storytelling are things I do because I’ve been compelled to do them since childhood, and doing them is the most rewarding thing I know.

Maps and BurritosUnable to hike on Sundays, I drive to somewhere even more remote than my hometown where I can spend time outdoors and get a midday meal. Since discovering a wooden relief map in this visitor center years ago, I’ve been wanting to return and photograph it. Unfortunately the plexiglass cover results in excessive glare.

I spent a few hours reading beside this creek.

No matter what else is on the menu – seafood, steak, burgers, Thai, sushi – if there’s a half decent burrito I’ll always order that. But it feels bizarre to be eating it at midday instead of after a long hike.

Storms are forming and rain is falling, but not enough. Still, our skies are as spectacular as ever.

July 21, 2024

Losing a Mind, Finding a Soul

I went for a short hike near town – the start of a longer hike I do regularly when I don’t have a hurt knee. This first stretch gently ascends a canyon bottom on a primitive road, finally becoming a foot trail nearly two miles up the canyon.

Returning down the road I encountered an older couple. The man looked like a 19th-century outlaw, with bright eyes, an impressive mustache, and a hat I envied. We agreed that the canyon was surprisingly dry considering the rain we’d had in the past week. That led to talk of climate change, and a world that’s going to hell in a handbasket. As locals, we agreed that we’re probably living in the best possible place – high in the mountains and far from the crowds. The man said “I’m just glad this is all happening at the end of my life – kids today are facing a bleak future.”

Not wanting to end on such a sour note, I replied “Well, the canyon’s full of beautiful flowers and butterflies today.”

The man smiled. “A friend told me he goes to the forest to lose his mind and find his soul.”

Enjoy the flowers and butterflies!

July 18, 2024

High on the Crest

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but they often suck at expressing the feelings inspired in nature. My current series of Dispatches reports on hikes or drives to the 9,000 foot crest of various Southwestern mountain ranges, but I’ve gradually realized that neither the pictures nor my reports have conveyed the feelings these places inspire.

I literally become ecstatic when I reach the crest of a mountain range, especially if it includes an unobstructed view to one or both sides, across the landscape thousands of feet below. That experience is the goal of my favorite hikes. In the major ranges of the Southwest, the crest averages 9,000 feet in elevation, 4,000 feet above the alluvial fans at their feet. In the Mojave Desert, the crests are much lower, as are the surrounding basins – the ridgelines of my favorite desert range seldom reach 5,000 feet, whereas the alluvial fans lie 1,000 to 2,000 feet below. But the feeling I get is the same regardless of the numbers.

Why? What is a crest, and why is it special?

Of course there’s the view – climbing from one side, when you reach the crest, you discover a whole new world, as far as the eye can see. The crest is where the weather happens – air is squeezed, wind funnels across, clouds form, rain or snow falls. A crest defines watersheds – the high line that diverts creeks to one side or the other. Reaching the crest fills my heart to bursting.

On the way to a doctor’s appointment in Tucson, I noticed the eastbound lanes of the interstate were under construction. With all that driving, I wondered if there was a chance of getting a short hike in. So on my return, I took a detour off the backed-up interstate. I knew there was a forest road that crossed the crest of one of my favorite ranges, and I’d seen it from far away, snaking up the mountain, but I’d never driven it. If I could drive up there, I might be able to hike the crest trail for a mile or two without taxing my knee.

It was a beautiful drive on a spine-hammering road starting out as deeply washboarded gravel, rising in single-lane hairpin turns on hard-packed dirt, rocks up to two feet in diameter embedded in hard-packed dirt, and ledges of solid bedrock. It took forty-five minutes to drive the ten miles to the crest. I passed several deer, and in a shady grove in the foothillls, a group of kids on an outing supervised by two women. But I didn’t pass another vehicle all morning on that narrow, twisting road.

I was thrilled to reach the crest, to cross the watershed and glimpse the eastern landscape, the mountains I was familiar with from many previous trips. Here a side road continues a thousand feet higher to a campground in the sky. I drove below tall firs that emphasized the altitude – everywhere there was a feeling of being on top of the world. I passed some kind of official crew camping at a dispersed site in a grove of giants below the road – they were gone when I returned in the afternoon. At the 8,400-foot campground I saw one RV, but apart from me and these there wasn’t another vehicle on the mountain. I parked, breathed the clean high-elevation air, and ate the tacos I’d picked up on the way.

The crest trail starts at the parking area outside the campground, and climbs through a fern-covered burn scar. It was hot out in the open – probably in the mid-80s. The trail traversed above and around the campground, and nearing the actual crest I came to a side trail, and followed it to a small saddle where I got my first view west. Clouds were building over the mountains south of me, and the west looked stormy.

I rejoined the main trail, which continues traversing across the east side of the crest, through patches of shade and thickets of thorny locust, and onto a narrow ledge below a sheer cliff. Past the cliff, the trail curves back into a hollow where I came upon an older couple struggling to control two big dogs – the people from the RV. Patches of forest and burn scar alternated across the slopes, jays and woodpeckers flitted through the trees and snags above me. Eventually the trail reached a saddle on the crest. I’d intended to turn back here, but there wasn’t much of a view, so I kept climbing.

Past the saddle, the trial climbs steeply through more burn scar, to a sort of barren hump with an expansive view west. I made my way to a rock outcrop, from which I could see rain falling out in the plain. But an outlying ridge blocked my view south, so I decided to climb even higher.

I reached a small hollow that was choked with ferns, charred logs, and thickets of locust. I tried going off-trail, hoping to get a view, but found myself blocked by forest. So I returned to the trail and continued still higher, out of the jungle and around the shoulder of the outlying ridge, and here I found my view to the south, at an elevation of 9,100 feet.

I was just shedding my pack and digging for my water bottle when I heard the sound of jets. It was two A-10 Warthogs, a fearsome machine designed to fly low and obliterate people and vehicles on the ground. They were flying up the canyon below me, just above the trees, and I watched them cross the crest in front of me.

On the way back, I detoured off the crest trail and down onto a very primitive forest road, hoping it would be easier on my knee and give me better views to the east. But it was so rocky I had to walk very slow – tottering between a problem foot on one side and a problem knee on the other.

At one point I heard screeching high above, and turned to see two golden eagles circling each other. Later, in a shady grove of tall firs, I came upon an empty Forest Service “Guard Station” – rustic cabins used periodically by work crews. Everything here felt high, remote, and lonely. Far from the world of screens, cities, celebrities, the rich and powerful and their advanced technologies – except that killer jets could thunder past at any moment.

Driving back down the crest road I passed a side road to another “park” – rural vernacular for a level place on top of a mountain. As I was checking my map, an old guy on a motorcycle approached and passed me.

I got turned around and climbed the side road, over a ridge and down into a densely forested basin, where I noticed the motorcyclist on the road below me. I finally emerged in the “park” – a grassy meadow surrounded by fir forest, with informal dispersed campsites, all empty. The motorcyclist passed me again and returned up the road without stopping – apparently just out for a ride in the sky, no need to get off the bike.

Shortly after I started back up the road, I encountered a big pickup pulling a loaded horse trailer down that steep, rocky trail. There was barely enough room for me to pull over, and the driver was staring straight ahead with his jaw clenched.

I began thinking about the RV at the campground. Most of these roads are single-width, and trees often fall across them. Rigs like that sure couldn’t back up in an emergency, and there’s absolutely no space for them to turn around. I guess they just count on other people to come by and save them if anything goes wrong.

Now I would continue down the main road off the crest to the east, and I immediately found that it’s just as bad as its western counterpart, and I could go no faster. But now it was like rush hour, one vehicle after the other passing me on their way up the hairpin turns. I had to pull over and stop to let the motorcycle guy past for the third time – he was going twice as fast as me, bouncing over all those rocks.

Halfway down I was approaching another blind turn when out shot a late-model minivan. The driver saw me and slammed on the brakes, going into a slide toward the sheer drop-off, his tires catching at the last minute. I pulled over, stopped, and rolled down my window, shouting “Slow down!” as he pulled alongside. It was a vanload of students on a field trip with their bearded, conservatively-dressed professor driving. He responded with a big smile, saying “How ya doin?”

I understood the rancher types with their pickups and trailers – they’ll drive anywhere. But I couldn’t fathom people who would drive minivans – let alone big RVs – up a rocky, narrow, seemingly high-clearance road like this.

Again, I passed lots of deer – mule deer, all very small. When I finally reached the oak-studded foothills, I came upon another big truck towing an even bigger horse trailer, the animals all sticking their heads out the side to watch me pass. This truck had broken down on the road, and its young cowboy driver was sitting in a folding chair behind the trailer. He said a hose had burst and his wife was on her way to get a replacement. Down here it was in the mid-90s.

After bouncing over rocks for hours, never knowing who was going to show up around those hairpin curves, my nerves were completely shot by the time I reached the paved road in the canyon. I got dinner and beer at the cafe, and decided to grab a room for the night – the only other option was driving home in the dark. But my troubles didn’t end there – it was over 90 degrees in the room and took three hours for the window air conditioner to cool it down. Makes a better story that way, right?

July 15, 2024

Long Drive for a Short Hike

To help my knee recover, I was preparing for a major change in my lifestyle and routines – daily short walks around town instead of long weekly hikes in remote mountain wilderness areas. But I still wanted to get out in nature on Sunday, and it was still hot, so I was desperate for a shady, high-elevation hike with little elevation change.

Since it would be a short hike, I could justify a longer drive, and there’s a ridge trail on the Arizona border, in one of the most remote parts of our region, that I’d been saving for a situation like this. It runs south from the rugged backcountry road that leads to the “valley at the end of the world” that I’d explored last October. I knew it would be forested, at least at the start, and it offers the option of a side trip with a total of four miles out-and-back and less than 500 feet of elevation change.

Driving toward the turnoff at a high point on the highway, I watched a range of mountains in the northwest, a range I’ve seen and driven past dozens of times – and driven through once – but have never been able to figure out. The topography from a distance doesn’t intuitively match the topography once you’re in it. I vowed to study the topo map in detail at home later, drawing a transect across the high points and comparing it with the profile as seen from the road.

The backcountry road is difficult and slow, but the most spectacular in our region. It winds up over a low forested divide, then down into the broad forested valley of a major creek, then up over an exposed pass with a forever view, down into the narrow forested canyon of a tributary creek, and finally up onto a forested plateau at 7,200 feet. None of this is visible from the highway. Despite the road featuring a popular campground and a series of dispersed campsites, I only passed one other vehicle in 13 miles.

The trailhead is just past the Arizona state line. Getting out, I realized this hike wasn’t going to meet all my criteria – it simply wasn’t high enough for cooler temps. It was already noon and the temperature here was in the mid-80s. And the plateau forest, a mixture of ponderosa, pinyon, Gambel oak, and alligator juniper, was open enough that shade was spotty.

The trail showed no recent bootprints but was well-traveled by cattle and horses, and it started out fairly level. Early on, it ran near the rim of the plateau and I got a view west over the “lost valley” toward the distant 9,000-foot Mogollon Rim. I saw a wildflower I’ve never seen in our local mountains, but couldn’t easily get my camera to focus on it.

The trail traversed down into a shallow gully and passed a junction with a mostly abandoned side trail that crosses back into New Mexico. Past the junction, the main trail got rockier, with more ups and downs, entered a recent burn scar, and eventually emerged on the rim of a big side canyon, where my map showed it would descend 400 vertical feet. To save my knee, I would turn back and explore the side trail I’d passed earlier.

Fortunately this canyon rim featured rimrock that made it a rewarding destination in itself.

I returned to the junction, and a short distance down the side trail I found a gate and wilderness signs, marking the state line. The tread was faint, overgrown in spots, and occasionally blocked by logs, but I had no trouble following it. Parts of the surrounding slopes were sadly overgrazed. When the trail started climbing between a series of low peaks, I climbed just high enough to get my bearings on the topo map, then turned back.

Back at the trailhead, it was after 2 pm, and I’d hoped to stop at a cafe on the highway for a late lunch, but the cafe closes at 3. I really didn’t want to repeat that difficult road, and wasn’t sure I could make it in time that way. My other option was the road over the mountains, where I’d been stopped by fallen trees the last time I’d tried it. I decided to try it again.

It’s another spectacular road, but since I was hurrying I didn’t stop for photos of the views. It basically climbs the crest of this small mountain range, through dense and mostly intact fir-and-aspen forest, to the shoulder of the summit at 8,700 feet, and then descends steeply to an 8,000-foot pass on the highway. It’s a 15-mile drive on gravel and rock, and to my chagrin, took 50 minutes, so I missed lunch at the cafe. On straight roads my vehicle is slower than most, but on this extremely twisty one you couldn’t make better time without sliding off and plunging hundreds of feet to your death.

Still, it’s a beautiful and really remote landscape, I didn’t see another vehicle anywhere up there, and I was glad I’d finally explored it.

By the time I got home, I’d spent 5-1/2 hours driving and 2 hours hiking. I wonder if most Sundays will be like this while my knee recovers?

I did study the map at home and finally discovered that those mountains I’ve always watched from the highway are indeed a named range, but a little-known one that’s omitted from most maps. The backcountry road crosses the middle of the crest as viewed from the highway, which is counterintuitive because the profile from the east masks the interior topography. It’s really complex, but I’m starting to figure it out. The only bummer is that all of it, including the wilderness area and the high peaks, is overrun with cattle.

July 8, 2024

High Priced Views

Sunday was forecast to be clear across the area, with a high in town of 95. I faced the same old challenge, finding a hike that would keep me out of the heat without crippling my knee. Reviewing the map of hikes I’ve already completed, I noticed there was a gap in the crest trail east of town. At over 9,000 feet average elevation, it should be cooler, and hiking it would connect previous hikes on the northern and southern segments, yielding a total of 21 continuous miles hiked on that crest.

The out-and-back distance would be ten miles with an accumulated elevation gain of 2,200 feet, which is about all my knee can handle now. The only problem was that the access road is the worst in our region, requiring all of my vehicle’s ground clearance in low-range 4wd to climb over 3,000 vertical feet of exposed bedrock ledges. I’d only driven the entire road once, and had sworn never to do it again.

Plus, I didn’t know what kind of trail conditions to expect – would it be cleared or blocked by logs and overgrowth? There had been two mega-wildfires across that crest – would I find shady forest or exposed thickets? Fortunately, there was a shaded option about an hour’s drive downhill if the crest hike didn’t work out.

I can take the lower gravel-and-rock-lined half of the road at an average of 30 mph, but my vehicle’s safe average on the second half – a distance of seven miles – is 5 mph, with much of it at less than walking speed. Still, I was feeling pretty good until I reached the 9,400 foot turnout for the trailhead, and the inside door handle broke off when I tried to get out. No problem, I just rolled the window down and opened the door using the outside handle.

Then I stepped out into the sunlight, and it already felt like the mid-90s at 10 am. Not a cloud in the sky, not a breeze in the air. Maybe this wasn’t such a great idea, but it’d taken me more than two hours to get here – I was committed whether I liked it or not.

Another reason why I’d chosen this hike was because it started with a descent, and hence ended with an ascent, which would be easier on my knee. At the beginning, it teased me with a patch of shady forest, then confronted me with a wall of New Mexico locust. The locust, the first wave of regrowth after the alpine mixed-conifer forest had been burned off, had grown to ten or twelve feet tall, and covered the ridges and slopes in virulent green as far as the eye could see, interrupted only by scattered patches of surviving forest.

My route forward was indicated by a shoulder-height corridor of younger growth through the mature thicket. Apparently a crew had cleared a path a few years ago, and new growth had completely fill it in since then. Virtually no one had used this trail in the past decade, so on the ground below, there was no tread – no actual trail – at all. There was only hard, uneven dirt. Not only did I have to push my way through a thicket of thorns, I was continually stubbing my toe or tripping over the stumps that the earlier trail crew had left, which were now hidden under the regrowth.

I’d had a lot of experience with locust thickets before, but never this much – this was probably a hundred times what I’ve encountered elsewhere. It shows how much we lost in these fires, that hundreds of square miles of forest were replaced by this. Of course the main impact is on the native ecosystem, but for me, it involves always hiking in long sleeves and long pants made from a rugged material, and holding my arms upraised in front of me, twisting from side to side as I push forward, to deflect the thorny branches.

Ridge trails wind up and down and around high points and saddles, and the thickets were interrupted often enough by trees that I could occasionally escape the burning high-altitude sun. I saw and heard lots of birds, and although my route was only sparsely scattered with wildflowers, butterflies and other pollinators were abundant.

After about a mile, I came upon what was obviously an old, long-abandoned forest road, and remnants of that would reappear over the next few miles. This led me from the 9,400 foot level to the 9,000 foot level, around which the remainder of the route would oscillate.

My main purpose in taking this route was to see unfamiliar parts of the landscape, to complete my mental map. But in this early stretch, I didn’t see anything I hadn’t already seen from other angles.

I’d brought a map, and after two miles I knew I was approaching a major saddle, a divide between east and west, at the head of a long west-side canyon. That would be a little more than halfway.

I reached the expected saddle and found myself looking down a long, wide canyon, eerily deforested by the wildfires and lined with bright green locust and Gambel oak. My map didn’t show the name, and it wasn’t until reaching the next big canyon that I realized this is the one hikers sometimes use to do a loop with the next trail. A cairn in the middle of the saddle marked the point where the canyon trail came up, and I followed it a ways down, but it seemed to be equally overgrown with even less tread.

From the beginning, I’d found big logs cut to make way for the trail, which I assumed had been done long ago, after the 2013 wildfire. But now I was beginning to notice logs that seemed to have been cut recently, often surrounded by sawdust. And past the cairn for the big canyon, the nature of my route completely changed. It was lined with cowshit, and occasionally horseshit, and dotted with the invasive grasses that cattle spread. Luckily the cowpies were at least a year old, maybe more.

And I found bear scat only a few hours old, and started making more noise to announce myself.

Past the saddle the route seemed to climb forever, once again through a wide swath like an old road, until it finally crested on a long plateau with expansive views to east and west. The view to the east was across a high, rolling basin, and at the southeast end of it was the 10,000 foot peak I climbed two weeks ago. I’d never seen it from this angle, and today’s hike was intended to link up with the trail I take north from that peak. The long plateau also brought the first breezes of the day, a huge relief in such an exposed position.

I was also joined on my right by a barbed-wire fence; west was cattle country, and east was federal wilderness – but the cowpies on my side proved the fence wasn’t holding.

At the end of the long plateau my route began traversing the west slopes of a series of hills. The old roadway ended and most traces of the route disappeared. I followed what looked like faint animal trails, always keeping the fence in sight below. The fence trended gradually downwards, so I knew I was heading for the junction saddle that would be my turnaround point.

I knew I was on the right track when I came upon a cairn, followed by a ponderosa with a blaze in its bark – neither of which were accompanied by a trail. After a mile and a half, the barest vestige of a trail appeared, and I emerged on the rim of the next big canyon, and saw my old familiar trail descending the opposite slope, with the high peak behind it in the east. That peak is an old friend, and I was now seeing the back side, which I’ve hiked so many times, in perspective for the first time.

Below, I could now see my current route continuing down to the saddle, but I’d visited that saddle many times and it held no attraction. This canyon rim view provided a much better turning point.

It’d taken me four hours to go five miles, fighting through that locust. I dreaded the hike back, especially since it involved more uphill in this heat. It seemed to take forever to reach that midway saddle, but I was so tired I wasn’t even aware I’d passed it, so that in the end, I suddenly found myself facing the final ascent by surprise. That last stretch was the hardest, especially knowing I had that nerve-wracking drive left to do.

With so much locust to push through, I was constantly reminded of how important my hiking clothes are. You can’t get clothes like this at REI – they make outdoorwear as if wildfire never existed, using thin synthetic fabrics that are expensive and wouldn’t last one day in these conditions.

My shirts are made from chambray, a lightweight but tough cotton weave, and my pants are canvas. Thorns do tug at them and they don’t last forever, but they do last at least a year, which for me means up to 1,000 miles of hiking. There are tougher fabrics, but they’d be too hot in our summers.

After seeing dozens of logs sawn through recently to clear this route, I was puzzled that the trail crew didn’t attempt to clear the locust thickets. At home that night, I found an online report that a Forest Service crew from Montana had cut those logs in April. Apparently they were only equipped, or only had time, for sawing logs, so they just pushed through the locust like me. Or maybe they were horseback, and made their horses endure the thorns?

I made much better time returning – five miles in three hours – but the drive down the mountain took 50 percent longer. I hope I never try it again.