Max Carmichael's Blog, page 10

October 23, 2023

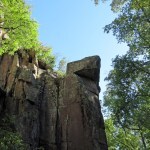

Lonely Tower

I started this Sunday with a conflict between need and desire. I needed to go easier on my problem foot, but I desired to see some fall color, which would most likely occur at higher elevation – entailing lot of climbing. None of my options were good, so my departure was delayed 90 minutes while I tried to make up my mind. Fortunately, the hike I settled on was in Arizona, where I would get an hour back crossing the state line. And although it involves a strenuous climb, it’s shorter than my usual Sunday hikes. I told myself I could take it slow to protect my foot.

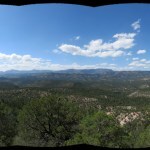

The sky was clear, and the high was forecast to be in the mid-80s at the bottom. It was in the 70s when I set out, but it already felt like the 80s in the sun, and the first mile is exposed, as you climb above the northeast valley. The only tracks I saw were from the small herd of equines that grazes the lower slope, which surprised me, since this is the most popular trail in the area and fall is peak hiking season.

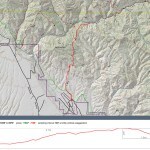

This trail, which I’ve hiked four times before, ascends the northeast and north slopes of a massif that stands alone surrounded by valleys, which are themselves surrounded by higher ridges. The top is essentially a lookout post for the entire northeast part of the mountain range, and in the past, a fire lookout was built and used up there. It’s a pretty hike with a lot of exposed rock and dramatic transitions between habitats.

Finally, as I left the foothills to traverse the northeast slope of the mountain, I got a little intermittent breeze and my mood improved.

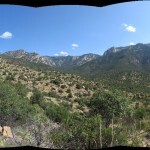

After climbing over 1,200 vertical feet, you turn a corner away from the northeast valley and into a big ravine that runs down between the twin peaks of the mountain. From here you view the northwest skyline of the range. And here I found my fall color, tucked into a corner of the steep ravine. You can also see your destination from here, high above to the southwest.

Long traverses and many switchbacks take you up into the cleft of the ravine, where you pass through a small stand of firs. The outer slopes are lined with oaks and pinyon pine, but these firs survive in the narrow ravine that channels cool air to lower elevations.

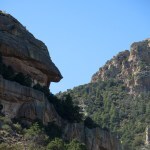

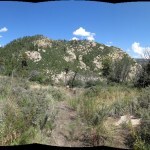

Past the ravine you traverse higher up the north slope until you enter the small fir forest that clings to the steep north slope of the peak, which tops out just over 8,000 feet. There, the trail passes behind towers of stone and begins a series of ten switchbacks that take you to the crest. I always find this stretch challenging, regardless of my conditioning.

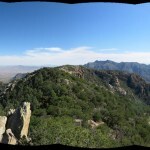

The summit ridge is like a knife edge, making for a dramatic climax to all those switchbacks. The big basin south of this mountain is suddenly laid out for you. And at the west end of the ridge are the vertiginous stairs that lead to the abandoned foundation of the lookout.

The weather was perfect up there. I really hated to leave, and procrastinated as much as I could. Interestingly, the summit register showed a lot of visitors, even during the hottest days of our summer heat wave, up until ten days ago. Despite being perfect weather, this was the first time I’d made this climb without running into other people.

On the descent, just as I left the fir forest something small and dark flitted out of the low grass and annuals on the slope next to the trail – I first thought it was a butterfly. But it dove into a clump of bunchgrass, and kept hopping about, clinging for less than a second to the dead stalk of an annual then hopping to the ground. And so forth. I was some kind of tiny bird, barely bigger than a hummingbird, keeping within less than a foot of the ground, moving so often I couldn’t focus the camera on it. I stood there trying to snap pictures as it hopped to and fro only four or five feet away, completely ignoring me.

After descending the other three series of switchbacks and traversing out of the steep ravine, I found myself back in the northeast valley, with the sun casting long shadows. Here, I’m always dazzled by the colors of dying agaves.

At the base of the foothills, nearing the trailhead, I came upon the horses and mules. My foot was sore, but not as bad as on other hikes since I started changing my gait. I sure wish my podiatrist hadn’t retired!

October 16, 2023

Long Way Down

The medical scare and trip to Tucson had screwed up this week’s schedule. I probably should’ve skipped my Sunday hike, but it felt like the only thing I could salvage to feel good about the week.

But I got up late, so I would have to find a shorter trail close to town. The one I picked is almost 12 miles out-and-back, starting from a long dirt road and descending over 2,000 feet into the canyon of one of our biggest creeks, just before the mouth where it joins the river. I prefer to start out climbing and finish by descending, but I figured it was “only 2,000 feet” – I’m used to twice that in my Sunday hikes.

The dirt road begins 18 miles north of town, about a 40 minute drive on the highway. I’d never explored it before, and was mildly surprised to find it pretty damn rugged, with a lot of exposed bedrock and steep, winding grades, so that it took me another 40 minutes to go another 7 miles. The long 8,600 foot high ridge that I’ve hiked many times loomed above on my left – this road skirts its steep north slope – and I got a new view of the burn scars from the 2020 wildfire.

Rounding a rocky bend into a side gully, I surprised a small hawk which had just caught a squirrel. Struggling to take off with its heavy prey, it literally dragged the squirrel through the dirt until it reached the dropoff on the other side and could soar across the gully into the lower forest.

I didn’t meet any humans on the road, but there was a pickup with extended ramp, and a detached flatbed trailer, parked at the trailhead. There was also a corral and lots of cowshit, all more than a week old.

The trail starts in ponderosa forest, down a shallow canyon next to a barbed-wire fence. I saw only one human footprint, going down; the other recent visitors had been on horseback, weeks or months ago.

The fence soon veered off, and although the creek was dry, lush vegetation and rocky bluffs made the canyon pretty. I hadn’t studied the map in detail and was surprised when, after a mile and a half, the trail began climbing away on the west slope. And I was really disappointed to meet my nemesis, the dreaded volcanic cobbles. My feet were not looking forward to this.

All I could think of, picking my way carefully over those rocks, was that I was adding to the elevation I’d have to regain on the way back. But as usual, I kept going, and was finally surprised to reach a dirt forest road that didn’t show up on my map. The trail apparently continued on the road.

And the road ran, fairly level, for a mile and a quarter, out a finger of ridge in a stark corridor that had been logged, partly as a firebreak and partly by woodcutters. Near the end, I heard chopping, and encountered a guy swinging an axe, splitting logs that had been cut into short sections by the Feds. “Free wood!” he enthused. His truck was nowhere to be seen so I assumed he was expecting a ride later.

On the positive side, I got occasional glimpses of the big canyons ahead. And finally the road ended at the wilderness boundary, and I faced the descent.

The trail into the big canyon started steep and even rockier than before. I immediately realized I should give up and turn back. But then I saw somebody coming up, in bright colors. It was a young through-hiker, finishing the national trail in reverse.

I’d read somewhere, recently, that the latest fad in the through-hiking subculture is to compete for the most outlandish outfit, but this was the first time I’d seen it in person. Forget the sleek, expensive space-age creations from REI – this kid could’ve just stepped out of a flea-market circus, his broad floppy hat ringed with big rainbow-colored fake flowers, and below that a garish striped shirt and mismatched paisley pants. Imagine tramping alone through thousands of miles of federal wilderness and national forest, camping along remote streams and rivers, just waiting for that moment when you can impress another young hiker – hopefully the opposite sex – with your bizarre costume!

I asked how far he’d come today, and he said about twelve miles – and he’d hated to leave the river, with little or no water between here and town. I realized the mountain biker I’d met cutting logs on the real national trail, earlier this year, had been right. No through hiker uses the official trail anymore, when they can follow the river instead.

We talked awhile, but if I was going to do this I needed to get going. He said “Enjoy the views!” which I did find encouraging. I wondered how much water he was carrying, and how far he would get tonight. We were 17 miles from the highway, on the other side of the high ridge, with another 12 miles from there to town.

The views did get better, but the upper part of the trail was a nightmare of rocks. My masochistic side took over – I’d come this far, I had to get somewhere nice before turning back. Down and down I went into the big canyon, and much of the trail was exposed, on a still day with solar heating.

I knew exactly where I was headed, because I’d hiked to the mouth of this canyon last year, along the opposite slope. That had been a much more spectacular hike because the opposite slope mostly consists of grassy meadows tended prehistorically by Native Americans, yielding views both long and deep, into the narrow, sycamore-lined canyon.

Still, it’s always exciting to hike deep into backcountry and encounter a site you’ve reached before, on an equally long trek through completely different terrain.

This is the driest time I’ve ever experienced in this region, and the creek was much lower, but still running. I was already in a lot of pain from the descent – I tried sitting on a log for a while, but knew I needed to get going. When planning the day, I’d ignored how much longer it would take to ascend than to descend. I would probably end the hike in the dark, starving and barely able to walk.

On the ascent, I discovered that walking too fast on the descent had given me shin splints and a sore knee. But I had to keep going, and I knew the hardest part was waiting near the top. I just shut down my mind and kept trudging, slipping and stubbing and stumbling among the rocks.

I made it up, and the hot sun was getting mercifully low as I paced out that interminable woodcutter road. The outlandish through-hiker’s footprints disappeared – he’d apparently bummed a ride with the woodcutter!

The trail down into the side canyon was even harder than I’d remembered, and the sun was setting by the time I reached the bottom. My entire lower body was on fire, but I knew the climb up this canyon to the trailhead would be easier. Dusk was beginning when I reached the vehicle – and the pickup and trailer were gone, probably belonging to the woodcutter and a partner.

I drove the 40 minutes back out the dirt road in the dusk. About halfway, I suddenly noticed a big bull elk standing on the bank just above the road, like a ghost.

My Tucson

I had to make a sudden, unplanned three-hour drive to Tucson for a medical exam. It took me a while to get ready, so I decided to stay overnight and hit the medical center the next morning.

Tucson is one of my long-time waystations. Its low-rise sprawl spans the huge basin below the 9,000 foot Santa Catalina mountains. I’ve visited most parts of that sprawl, from the airport in the far south (my favorite in the U.S.), to a friend’s house on Sabino Creek in the far east, to REI and Whole Foods in the far northwest, to the Sonoran Desert Museum (actually a zoo) just west of the city. My first-ever visit, more than 20 years ago, was downtown, to hipster hangout Hotel Congress. I stayed there twice, danced at the nightclub, and ate at the cafe dozens of times, beginning in 2006, as I commuted from New Mexico to San Diego on my longest-lasting tech industry contract.

So I know the city pretty well and have a few favorite places. One of those is the Reid Park DoubleTree hotel. I stayed there first in 2008, fifteen years ago. Reid Park, about four miles east of downtown, is dominated by a golf course, and the hotel is an affordable midscale resort and conference center. Many people say it’s in the middle of nowhere, but I routinely shop in that area, and there’s a wide variety of restaurants nearby. Like every Western city, Tucson has the full spectrum from cheap motels to trendy boutique hotels and luxury resorts. I’ve tried all extremes, but prefer the comfortable, unpretentious DoubleTree.

I last stayed there in 2018, and the place seems to be struggling in the wake of COVID. Their low occupancy rates can no longer sustain a restaurant – they serve breakfast, and a lobby bar features a limited food menu. But the staff is still friendly, the grounds are still clean, and the rooms are still being regularly renovated. I’ve stayed in the tower before, with a great view of the mountains, but this time I got a cheaper courtyard room – with a private patio shaded by orange trees. At the lobby bar, I enjoyed my favorite local IPA and one of the best burgers of my life.

The Hospital

The HospitalThis was a bizarre, disorienting trip in which I drove three hours to check into a big-city hospital Emergency Department for tests I couldn’t get at home, tests which would otherwise require months of waiting for an appointment. After last year’s nightmare illness, I dreaded being inside a hospital again, and was half hoping they’d turn me away.

But the staff accepted my situation and went right to work. I saw one doctor after another, and the second said they would keep me overnight – something I was ready for but not happy about. Then I waited four hours for an MRI, had a complete neurological exam, and was discharged – they’d found nothing wrong – after a total of eight hours in the maze-like bowels of the hospital.

I booked another night in another DoubleTree courtyard room, enjoyed a salad in the bar, and early to bed.

The Eclipse

The EclipseWanting to at least do something fun in the city before heading home, I found the nearby U of A was hosting an eclipse event. Visitors were advised to park in the Cherry Street garage, which I found on Google Maps. I drove through campus on Cherry Street, less than ten minutes before the maximum, but the garage didn’t seem to exist, a big crowd was swarming over the parklike intersection, and there was no street parking.

At the same time, my Native American friend was urgently trying to reach me, and I couldn’t keep dismissing his calls. So I drove off campus and found a shaded spot in front of a house where two women were putting up Halloween decorations. Before calling, I turned my notebook into an eclipse viewer, punching a hole in a page with my ballpoint pen, held it out my car window, and saw the crescent – Tucson was getting the 80% version.

The Museum

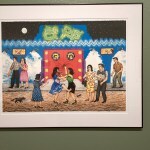

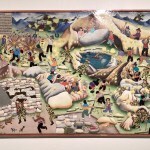

The MuseumAfter the call, it was almost time for the art museum to open. I’m a fan of regional art museums. In keeping with Latin culture, Tucson’s modest museum is built as an inward-facing courtyard, blank on the outside, incorporating historic adobe buildings along one side. Their permanent collection is poor, so temporary exhibitions are the draw. A sort of smaller, inverted, rectilinear Guggenheim, the building starts at street level and spirals underground.

I spent two hours there, longer than ever before, ending on the easily-overlooked upper floor, which hides, like an afterthought, a disappointing selection of modern art. There I found an Alexander Calder print featuring a spiral. He’d made a belt buckle with a silver version of that same spiral, and in high school, as a friend of the family, I made a belt for it.

Finding my way out, I hoped to eat at the busy cafe. But I was starving and it was all light fare.

The Restaurant

The RestaurantA few blocks up the street is a Mexican dinner house I’d tried before. When I travel from my small town to the big city, I have no interest in sushi, Thai, or any of the other exotic cuisines city people favor. Mexican food at home is so limited, all I’m interested in is better Mexican food.

The hostess put me in the far corner at the window, which was fine with me. But right next to me was an enclosed stone staircase leading to a dark cellar, and my waiter, a young gay man with bleached hair, said if the goblin bothered me, I should just toss it some chips.

October 9, 2023

Thunder Ridge

I’d come up with a theory that the pain in the outside of my foot was due to a combination of weak toes and a long-term shift of weight from the ball of my foot to the outside. Both were habits adopted to protect the ball of my foot from chronic inflammation – along with wearing stiff-soled hiking boots. So for this Sunday’s hike I wanted a fairly easy trail to practice correcting my gait.

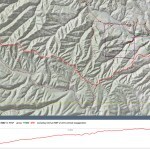

All the trails on the fringes of our wilderness are either in bad shape or involve steep climbs, so I decided to drive up to the heart of the mountains and take a ridge trail that runs westward 14 miles, ultimately connecting with the major west-side creek I hiked eastward to a couple weeks ago. Below this east-west ridge lies a narrow canyon in which a creek drains eastward, and the map shows a connector trail from the ridge down to the creek, that I could use to make a loop hike of about 14 miles round-trip.

I knew from a previous partial hike on this trail that the grades are gentle, and the ridge is only 400 feet above the canyon, so it shouldn’t be too hard on my foot. Even better, the trail had been reported cleared last year, and I didn’t remember it being very rocky.

The morning was chilly, but the sky only showed a few distant filaments of cloud and the high was forecast to be in the low 70s. Trails in this area are popular with tourists, and there were couple of horse trailers, a pickup, and a school bus from Colorado parked around the trailhead. I found it fairly easy to concentrate on my gait, and the climb to the ridgetop warmed me up. It’s 3-1/2 miles to the first junction, where I’d turned south on my past visit. This ridge offers long views to the north and east, but nothing particularly spectacular. It’s just nice being on a ridge, having views to both sides, and despite the “mindful walking”, I made good time.

Past the junction I entered unfamiliar ground. Despite being an easy trail, it maintained interest by crossing a series of knife-edge saddles with yawning views, then traversing mostly bare slopes consisting of white conglomerate terraces. Most of the canyons in this area are lined with bluffs of white conglomerate, sometimes containing caves where prehistoric people built modest cliff dwellings.

The habitat alternated between scrub, pinyon-juniper-oak woodland, and open ponderosa pine forest. But the ridgetop trail was mostly exposed, and the air was mostly still. Solar radiation made it feel like the 80s.

I was still moving at a good pace, and based on the time it took me to reach the first junction, I started watching for the connector trail that drops into the canyon on my left. But I kept going, half hour by half hour segment, and never saw any sign of another trail.

From the lower part of the ridge, the view to the northeast had been the main attraction. But now, a series of peaks to the southwest formed my horizon, getting closer and closer across the canyon of the creek below. Whereas most of the ridgetop is burn scar, the canyon and slopes on my left were darkly forested with ponderosa pine.

Trudging onward, focusing relentlessly on my gait, I began to realize I’d somehow missed the connector trail. No problem – I’d just turn back when half my time was gone. But my foot was getting tired and I wanted to stop somewhere where there was a nice shady spot to rest. Those were few and far between on this exposed ridgetop.

Eventually I came to a small clearing with a spreading juniper, took off my boots and relaxed for a while in the shade. I figured I’d gone between 7 and 8 miles.

On the way back, I looked more closely for the connector trail, and never saw the slightest sign of it. In fact, it doesn’t exist on Forest Service maps – it probably ended up on my mapping platform because some dude bushwhacked down there once, capturing his route on GPS.

Cumulus clouds had been building on the northwest horizon, forming a dark mass that gradually loomed over me. Thunder was booming almost continuously up in the clouds, but I couldn’t see any lightning yet. I wasn’t looking forward to hiking this exposed ridge in a storm.

First I felt a few drops, and then it began to fall in earnest, so I pulled on my poncho and speeded up. Both feet were hurting, and I had a cramp in my left hip that was making my whole leg numb.

I walked in rain for a half hour, thunder rolling overhead, as the storm spread to cover the entire visible landscape. When the rain moved off, I could see lightning far in the east, but thunder still boomed overhead. The trail becomes even more exposed at the east end of the ridge, where I began to feel really vulnerable. I couldn’t remember ever hurting this much at the end of a hike. But my theory had worked – there was no more pain on the outside of my foot. And on the final descent to the trailhead, the sun came out and the colors were glorious.

It’s a long, difficult drive home through the mountains, where I faced sporadic rain and switched into 4wd to keep from sliding off a precipice. Town was dry, but within a block of home the heavens opened up and we got a brief but heavy downpour.

October 2, 2023

Valley at the End of the World

There’s a large, mountainous area near here that I drive past regularly, on our loneliest regional highway, on long trips to other places – yet for seventeen years it’s remained a mystery.

The area encompasses 1,200 square miles, all within national forests, and is so rugged that it contains virtually no level ground. I knew it has a named mountain range, but from outside, it’s impossible to distinguish that from other, better known mountains. Landforms intrigue me and it really rankled that I couldn’t figure out the topography of this region.

From maps, I could see it contains a river, but the canyon or valley of that river can’t be seen from outside and would take hours to reach on dirt roads. The same maps show a network of hiking trails crisscrossing most of the area, and I’d tried two of those trails on the far east side closest to my home. One was abandoned and lined with sharp rocks, the other was abandoned and heavily used by cattle.

I’d avoided exploring this area because, in addition to being overrun with cattle, I’d assumed most of it was below 8,000 feet elevation and hence less interesting than the surrounding higher mountains. But this Sunday I needed to give my problem foot a rest, and the weather was forecast to be mild, so I decided to explore the unknown land by vehicle.

The unknown land can only be reached by vehicle from the north or east, on one of four dirt roads that are rocky and require high clearance. The road nearest to home enters from the east, winding and climbing up and down through tall, parklike ponderosa forest at an average elevation of 6,500 feet. It took me a half hour to go six miles, where I reached the first milestone, a trailhead and campground. Whereas on my previous short forays on this road, I’d found every turnout occupied by a huge RV trailer, today the whole area was unoccupied.

When I stepped out of the vehicle at the trailhead, the wind almost blew me over, and I had to close the windows to keep blowing dust out. We hadn’t had wind like this since last spring – the tops of the pines were thrashing and roaring like a freight train.

In contrast with trails in my well-publicized local mountains, where a majority of visitors come from places like New York and California, the vast majority of the visitors listed on this trailhead log were from Arizona and New Mexico. I’d gotten a late start and ate a typical hiking lunch, sitting on a log in the shade. Apart from the wind, the temperature was perfect, and forecast to be mild all day.

As I drove away, a Forest Service ranger arrived in a maintenance vehicle – the only other vehicle I met on that road all day.

My next destination was a cliff dwelling which is marked, surprisingly, on Google Maps, another six miles up the road. Past the forested campground, the road climbed, and climbed, and climbed, becoming rockier and rockier, emerging from the ponderosa forest onto steep slopes dotted with shrubs and junipers, with fortress-like bluffs of volcanic conglomerate looming high above. I got a panoramic view of lower ridges and canyons to the south, and I kept scanning the cliffs above, seeing many caves but no cliff dwellings. So I zoomed in and took photos, hoping to spot the cliff dwellings later, when I had a chance to blow up the photos at home. Guess I should pack field glasses in my vehicle!

The road topped out on a knife-edge saddle with the most spectacular views I’ve seen from any road in this region. Above was the stone rampart, on the west was the deep canyon of the next watershed, and beyond the lower country in the southeast rose my familiar home mountains. I was forming my first mental map of this unknown land, and unexpectedly, I was impressed.

Past the saddle, the road wound down into the next watershed, becoming rockier and slower. It entered more pine forest, crossed the head of the new canyon, and climbed again onto a forested plateau between mountains on the north and south. Here I crossed the state line, met one of the dirt roads coming in from the north, and reached a second trailhead. The log at this one recorded mostly visitors from Phoenix or Tucson – a five-and-a-half hour drive away. My friends tend to dismiss Phoenix as a hotbed of ecological abuse, but I’ve learned that the sprawling, water-wasting megalopolis is actually full of nature-loving outdoor enthusiasts, with fantastic landscapes like the Superstition Mountains nearby. How had they found out about this remote, poorly-publicized area far to their east?

At the western end of the plateau I began my descent into the remote valley of the obscure river. The road became really vertiginous, with a dropoff of hundreds of feet, until I eventually reached a precarious wide spot to pull over and study the view. This was the hidden valley I’d wondered about for years!

I was surprised to spot isolated homes and ranches scattered throughout the darkly forested landscape, but I couldn’t see a floodplain – it seemed to be all steep ridges and deep canyons, and on the far side, the 9,000 foot rim of the alpine plateau I knew and loved from many previous trips. This valley had remained hidden from that high plateau.

At the bottom, the road passed a very funky compound, strewn with rundown buildings and dusty vehicles, and immediately forded the shallow river. Then on the other side sprawled a big, well-tended pasture with the kind of modern, upscale ranchhouse you see throughout rural Arizona.

The road wound down the valley, crossing and re-crossing the river, beneath a lush canopy bordered by sheer, dark volcanic cliffs. Homes and ranches were sparse, separated by long stretches of dense riparian forest, and the construction varied between traditional working ranches, funky weathered cabins, and what appeared to be the occasional modest vacation home. Most rural settlements in Arizona are very affluent compared to New Mexico – I hadn’t seen this kind of diversity elsewhere. The fact that the valley is populated at all was an unexpected revelation.

The river road dead-ends about fifteen miles downstream. I drove most of the way, checking out remote trailheads I’d always wondered about. Most of them seem to be used by equestrians, many of which are probably hunters living in towns a few hours away.

The wind was still roaring, and when the road occasionally climbed high above the river I could see it sweeping in waves across the billowing canopy of narrowleaf cottonwoods. Cumulus clouds were forming and I was wondering if I’d have to drive that marginal dirt road in the rain later. I also wondered where these people do their shopping. After checking the map I discovered the nearest gas is over an hour away, on another of these slow, rocky, high-clearance dirt roads. The nearest small town, with shopping, is an hour and a half. And this river must flood regularly, stranding residents from each other and the outside world for days, maybe even weeks at a time in a wet year.

I turned back north when the road became gnarlier, and pulled off at one of the trailheads I’d long wanted to explore. The trail started steep – bad for my foot – and was badly eroded, lined with sharp rocks, and used only by equestrians, so it was also deeply pitted. I only went about a half mile, far enough to climb several hundred feet above the river, to a saddle with partial views east and south.

I’d hoped to explore the upper valley, but my time was running out. I was also curious about the road that accesses the valley from the northeast, the road I’d passed up on the plateau. In fifteen miles, it climbs over the shoulder of a 9,000 foot peak and might offer more spectacular views. The extra distance meant I probably wouldn’t get home until after 7 pm.

I’d passed a total of four vehicles in the valley, but there was still no one on the upper roads, despite it being a weekend. The northeast road climbed gently through parklike ponderosa forest, then steeply up a ridge. I could tell there was an amazing view south, but only found one small break in the trees. Then the road turned down again into a hidden interior valley, and finally began climbing a long, narrow canyon that I believed led towards the high peak.

The habitat in this canyon was completely different – moist, and lined with a pure, dense stand of tall firs, with seedlings bordering the road. The wind was still roaring overhead, and I came to a fallen tree blocking the road. Why hadn’t I thought of this – blithely driving through forest in high wind?

Only six inches in diameter, the tree turned out to be easy to swivel to the side. But then the road entered a burn scar, and I came to tree after tree I had to move off the road. When would I reach one I couldn’t move?

That happened shortly afterward. A tree had fallen from a high bank so that it was wedged in place across the road. I couldn’t budge it by hand, and what if an even bigger one lay beyond? I had to turn back, and retrace my morning’s path on the slow eastern road.

Just before reaching the east-west road, I encountered a 4wd flatbed truck on big tires, with two guys in the cab. I waved them down and warned them about the fallen tree, but they were only going a short ways up the road and weren’t worried. After talking to them, I remembered I had heavy duty nylon straps in the back and might’ve been able to pull the fallen tree out of the way with my vehicle. Or not – there was still the likelihood of more, and the time wasted doing road work instead of driving home.

Of course, with the wind, the clouds, and the setting sun, the landscape just kept getting more beautiful. That eastern road into the valley has to be the most beautiful road in this entire region. In the words of the Governator, I’ll be back.

In the end, it took me six hours to drive 71 miles on those dirt roads, for an average of 12 mph. I ended up driving a total of nine and a half hours and got home in the dark exhausted, starving, and in pain.

If you wanted to escape civilization, that hidden valley might be your best option in the American Southwest. No, it’s not wilderness, and you’d have a motley collection of neighbors. But there’s plenty of water for living and gardening, wild birds and other game love riparian corridors like that, and the bad roads and flooding keep out the riffraff. And the whole area is far more spectacular than I’d ever imagined – truly a hidden gem.

September 25, 2023

Painful Paradise

It’d been almost exactly a year since a catastrophic flash flood washed out the road to one of my favorite nearby trails. At least I remembered it as one of my faves. The main road up the mesa leads to two trails, and I’d checked this one several times during the past year. As of April 30, the road was still impassable, and since July, the weather had been too hot to even consider this lower-elevation trail.

This Sunday was forecast to be clear and warm – in the low 80s in town. I headed out, and lo and behold, when I reached the turnoff, the “Road Not Passable” sign had been removed.

In fact, this far into a drought, the big creek was completely dry at the crossing.

This trail starts at 5,300 feet and winds up a shallow, rolling basin to the foot of a 7,700 foot mountain, where it switchbacks up over a 6,500 foot saddle and enters a big new watershed lined with white rock pinnacles. Back there, it traverses the forested upper slope of the mountain to a narrow ridge that trends northward like a bridge for a little over a mile, with a spectacular view north across a deep canyon to the crest of the range many miles away.

Then the trail drops into the wild, upstream canyon of the big creek that was dry where I crossed it on the way in, in long traverses and switchbacks, descending over 800 feet to where the creek flows perennially. Thus the attraction of this trail is crossing multiple watersheds, gaining spectacular views, getting way back in the wilderness to a place where you feel really remote, isolated, and fully immersed in wild nature.

With the road recently repaired and our heat wave ending, I turned out to be the first non-wild creature to hit this trail in a very long time – probably in the past year. And the drought meant that I was facing a fairly clear trail with very little overgrowth. But what I’d forgotten is that almost all of this trail is lined with rocks – really hard on my problem foot.

And like last week’s hike, although the air temperature was mild, the sun was damn hot, with not a cloud in the sky and not a hint of a breeze on that initial climb.

Past the saddle, I began to get a little cooling breeze. Having resigned myself to a hike where I spent most of my time concentrating on my footing, I made decent time past the saddle and across the seemingly interminable traverse of the mountain’s back side, reaching the next milestone, the small level “park” lined with tall pines – a rare and always welcome source of shade.

From the park there’s a lot of serious up and down as you head north on the narrow ridge. The latter half of this traverses a burn scar which is popular with wildlife. A lot of birds, very active. I spooked a whitetail buck there, but after he first ran uphill away from me, I next spotted him running downhill to a vantage point behind me. Then I came upon a dove that simply trundled up the trail a short distance ahead of me, reluctant to fly away.

Leaving the ridge, the descent into the remote canyon cooled me off, despite being mostly through burn scar. My foot was hurting already, but this stretch of trail is relatively rock-free, and I had pain pills for the return.

This is a trail which is not shown accurately on any maps I’ve been able to find. My mapping platform omits most of the switchbacks and reports the out-and-back distance at a little over 13 miles and almost 3,000 feet of elevation gain, but with the switchbacks and new routing, I’ve estimated it at 15 miles and almost 3,500 feet.

The creek is hidden beneath a deciduous canopy in a dense corridor of vegetation, so you hear its wonderful sound before you come upon it. I laid down on a gravel bar beside the water and spent fifteen minutes trying to sort out the trees overhead.

The climb back to the ridge would seem daunting if it didn’t unfold in many distinct sections, with increasingly rewarding views. But my foot was getting worse, so I popped a pill, knowing it wouldn’t take effect for another 45 minutes.

Out in the exposed burn scar of the ridge, I suddenly noticed a small hawk trying to catch a tiny bird. The two of them, hunter and prey, spiraled toward me, only a dozen feet above the hillside, until when they were right overhead the hawk noticed me and backed off. I’d accidentally saved the little bird from being eaten.

I also noticed another whitetail – or maybe the same one.

Past the pine park, it’s mostly downhill, and the rocks on the trail get really bad. Constantly focused on where to put the next foot, I became pretty good at it, but I still rolled my already weak ankle a total of three times, and swore to wrap it in the future.

The worst rocks are on the descent from the saddle to the final basin. It was there that I swore never to hike this trail again. It’s just too damn hard on the foot and too dangerous for the ankle. I suppose young people could do this kind of thing without even noticing it, but it always amazes me that a trail would even be built and maintained across such rocky ground.

On the plus side, throughout the final two-mile trudge down the low basin, quail were constantly exploding out of the brush next to me, over and over, every few minutes. It may have been the same coveys, just moving downhill ahead of me. Never seen anything like it.

I was exhausted after the hour-and-a-half drive home, but while unloading the vehicle I suddenly came upon a chicken – a blonde hen – in my back yard. She circled around me, clucking, then approached tentatively.

I hear a rooster from time to time and remembered my neighbor mentioning somebody a block away who has chickens, so I called next door. Meanwhile, the hen fluttered up onto the tall fence between our houses. My neighbor said it might be the people in the next block, so he walked over to check. It was starting to get dark, and the chicken stayed up on the fence.

The guy down the street arrived, along with my neighbor and his wife. “Is it blonde?” he asked, in a strong accent. I beckoned him over and showed him the chicken. “Yes! There she is! I won’t have to tell my wife we lost her!” He reached and grabbed the hen, cradling her in his arms. By that time, another neighbor had showed up in my driveway, carrying her kitten. My neighborhood has turned into a sort of commune.

September 18, 2023

Purgatory Ridge

Expecting cooler temperatures even in the lower, hotter mountain ranges across the border in Arizona, I finally enjoyed an abundance of choices for this Sunday’s hike. But when I reviewed the latest trip reports from the range I was missing the most, I was surprised to find that a trail that had stopped me more than four years ago had been cleared last fall, by convicts from the nearby state prison.

This trail climbs a ridge above the spectacular canyon that I finally hiked last December, before our snowpack got too deep. Both hikes lead to the 9,000 foot crest, but the ridge trail is actually longer – my mapping app shows it at six miles one-way, 12 miles out and back, topping out at 9,341 feet, accumulating just over 4,000 feet of elevation gain.

It’s a two-and-a-half hour drive, but I would leave early and gain an hour crossing the state line, so I hoped to start at the same time I usually begin local hikes. The hike, and the mountain range, are scarred by the prison I have to pass and the giant astrophysical observatory that dominates the skyline, but the rock formations, habitat, and wildlife more than make up for those deficits.

It’s designated a “Wilderness Study Area”, so the entire range is open to cattle, but they have such lush forage at low elevation that they seldom venture onto the slopes.

After our hot, dry summer, the perennial creek was running at an all-time low. Someone had stolen the trail sign, but as predicted, the trail itself was much easier to follow. I found fresh boot prints in the first hundred yards, but whoever had started out soon turned back. It appeared that I was the first on this trail since at least last spring, if not since last fall.

The trail climbs steeply to the ridge top, revealing a view of the big canyon on your right and the crest with its boxlike Large Binocular Telescope. The trail surface alternated between bare gravel, bedrock, and grass, and I was soon sweating and overheating, realizing that almost the entire route is exposed to the sun. Temperatures may have dropped across the region, but I’d picked the hottest trail possible.

Not only was it hot, it was a continuous steep climb, at a minimum grade of 15 percent. I was still out of shape relative to previous years, resulting in a lot of stops to catch my breath and mop the sweat off my face. Thankfully the flies mostly left me alone up on that dry ridge.

In one mercifully shady stretch I found a plaque commemorating last year’s convict work party.

This outlying ridge ascends to the crest by means of a series of small peaks, and as the trail reaches the foot of each one, it becomes a seemingly interminable series of switchbacks. These make the climb possible, but they also make it longer!

Past the gate with the convict plaque, the trail got harder to follow – it seems like they focused their work on the lower third of the trail. As usual, I rejoiced when I first encountered ponderosa pines, but the rocky terrain prevented them from establishing enough forest cover to cool me off. The air temperature wasn’t bad – it was the solar heating that was killing me.

As each of the ridge’s intervening peaks loomed in front of me, I was hoping it would be the last one before the crest. But again and again, I was disappointed, and began wondering if I really had it in me to finish the climb.

Finally, I found myself on the last series of switchbacks ascending to the crest. Here I had to climb over or around many deadfall logs and branches – it seemed that the convicts hadn’t made it this far, but someone had stuck little flags in the ground, many years ago, which usually indicates planned trail work that hasn’t actually taken place yet.

The last switchback unveiled the crest and the beginning of a burn scar colonized by aspen seedlings and thorny locust. But now, between me and the end of the trail, I faced a long, narrow bridge of rocky ground broken up into more little peaks. To cross this bridge I would have to ascend and descend each intervening peak. My map showed that after that hot, brutal climb, I still had almost a mile and a half of this to go. I couldn’t believe the entire trail is only six miles long!

The lizard population up here was exploding. It seemed like there were up to three lizards per square yard, including multiple species and sizes, and they were often hanging out together. I’d never seen anything like it.

The hike across the bridge involved even more obstacles and even steeper climbs, but I was determined to finish this damn hike, even if it meant limping back in the dark.

The Forest Service recommends hiking these trails downward from the crest, so I was watching every patch of bare ground for footprints. I still didn’t find any until I reached a fairly level stretch, where intact forest returned, only a quarter mile from the end. Apparently this trail is just too daunting for everyone but me.

A lovely patch of spruce-fir forest awaited me at the end, but that last quarter mile still felt endless. The ascent had taken me more than five hours, and the Forest Service sign contradicted the distances shown on my mapping platform. I had my pick of total distances for this hike, ranging from twelve to fifteen miles! My best estimate was thirteen and a half.

I didn’t have much time to rest at the top – my foot was hurting and it would only get worse. But that wasn’t the only thing slowing me down on the descent – my knees were complaining too, and I still had an ankle strain left over from a couple weeks ago. Combine a 4,000 foot descent with a steep, rocky trail, and you have a recipe for a lot of pain.

But if you could ignore the telescope above and the prison below, it remained a beautiful landscape, and once the pain pill took effect I was really glad I’d come.

Moving as fast as I could, it took me just over three hours to get back to the vehicle. I’d booked a cheap motel room, but that was well over an hour away. A comedy of errors followed, delaying my dinner until 9 pm, and bedtime until 10. Today I drive home. Call me a masochist.

September 11, 2023

Road in the Sky

This weekend was forecast to feature what I hoped was the last of our seemingly endless Southwest heat wave. Ironically, Sunday, my hiking day, was forecast to reach 90 in town, while highs in the following week were predicted to drop into the 70s.

I’d already done all the high-elevation hikes in our area, except one – the crest hike that requires a two-hour drive and traverses a moonscape burn scar with hundreds of logs across the trail. I was grimly determined to deal with both the drive and the logs, when at the last minute I remembered another crest route – a route I’d never considered because it’s not wilderness, and most of it consists of a road instead of a trail. At this point, even if I didn’t get much hiking in, it would be worth it just to escape the heat.

This route is approached from the west side of the north-south range east of town. I’ve delayed exploring this area until the past six months, because all the hikes must be accessed via long drives up long ridges – “finger” mesas – on rocky roads. After several tries, I’d given up – none of the trails have been cleared in the wake of two mega-wildfires, one in 2013 and one in 2022, that burned almost the entire crest of the range.

At 10,020 feet elevation in the south half of this range, the second-tallest peak hosts an active fire lookout, and I’ve climbed that many times on what is probably the best-maintained trail in our area. But in the north half of the range, there’s actually a forest road that climbs to a cabin less than two miles from the 10,165 foot summit.

It’s almost 18 miles from the highway at 6,200 feet to the cabin at 9,500 feet. I’d driven the lower 9 miles twice – the last mile of it is over sharp ledges of bedrock with a sheer dropoff and is very nerve-wracking. The upper 9 miles is widely reported to be one of the most brutal roads in existence, completely undriveable without high clearance and low-range 4wd. Since I was looking for more hiking and less driving, my plan was to try to drive within 7 or 8 miles of the summit, but I didn’t even know if that would be possible with my vehicle.

Since the road follows the crest of the range and spends about three miles traversing a burn scar up there, I would be exposed for most of the hike. I wasn’t worried about sun, since there would likely be a breeze across the north-south crest, but we were forecast to get clouds in the afternoon, and although I hoped for rain, lightning would be a real concern.

The vertiginous upper road climbs over 2,000 feet in the first six miles, and it turned out to be barely driveable in low-range with my 9 inch ground clearance, as I slowly pushed the little vehicle up a seemingly endless series of sharp bedrock ledges. Including the easy stretches, I averaged about 6 miles per hour.

I did bash the undercarriage pretty good in one spot, but the payoff was the views. Approaching the crest, I was facing the highest points in the range across a wide canyon that had been burned to a moonscape. I was looking for a saddle with a surviving stand of conifers where I could park in the shade, and I finally found one, at the site of a SNOTEL – a snow telemetry site maintained by the National Weather Service.

From the snow telemetry installation, I had about a four-mile walk on the road to the cabin, followed by about two miles on a trail I was sure was unmaintained and overgrown. But first, I was curious about the junction with the northbound crest trail, a trail I’d hiked many times from the south, and tried to reach recently from a canyon that parallels this road, below on my right.

The first thing I noticed was wildflowers – they were probably peaking now at this elevation, helped by the little moisture we’d received in the past two weeks. Then I reached the trail junction. I suddenly realized that although I’d be walking a road, the road here is actually a segment of the crest trail. That made me feel better – I wasn’t choosing to walk the road, it was actually the only route available.

Since the trail junction marks the beginning of the crest, it also marks the crossing to the eastern watershed. This is a huge watershed in which three long creeks cross a broad basin to merge into one at the bottom. The surrounding ridges and slopes are topographically diverse, ranging from cliffs and pinnacles to shallow slopes blanketed by annuals. I’d never seen any of it before so I made slow progress as I stopped to study the landscape opening out below me.

Walking the crest, I hadn’t expected much elevation gain or loss, but this is where I realized it would actually be a rollercoaster. My whole day would be spent ascending and descending hundreds of feet, crossing back and forth between eastern and western watersheds, over and over, up in the sky.

After about two-thirds of a mile with that eastward view, the road crossed to the other side, where I could view that badly burned canyon I’d seen on my way up. The stands of aspen and fir that had been killed in the fire created bands of black and tan on the slopes that alternated with white outcrops of volcanic conglomerate and green regrowth of locust and Gambel oak.

There are always hawks along a crest, and I encountered the first of the day here.

Finally I reached the cabin, and the end of the road, in a small forested basin facing east. I remembered seeing photos of this cabin on InciWeb, wrapped in foil to protect it during both of the big wildfires. Structures like this are where firefighters invest most of their effort.

I could barely discern the trail leaving the cabin for the peak. There was no sign, but there was a vague disturbance in the annual ground cover, heading up in the direction of the ruined outhouse. When I followed that, I noticed a branch veering off into the forest. No one but animals had used this trail in the current growing season – it was almost completely overgrown and blocked repeatedly by deadfall. But it had been used heavily by firefighters last summer, so there was enough tread left under the vegetation that I could read it by going slow.

Before approaching the summit, the trail climbs to a 9,800 foot peak – it’s actually hard to identify the summit from a distance because it’s surrounded by peaks that are only slightly lower. The almost invisible trail first crossed to the eastern slope, then at the top of the lower peak, crossed again into a new watershed that was tributary to the big canyon I’d seen on the drive up. I was crossing so many watersheds it was hard to keep track!

Past the lower peak, the trail traversed a steep slope that had been badly eroded and colonized by thorny locust. Here, I flushed a small hawk, not much more than a foot long, probably a Cooper’s or sharp-shinned. This was the slowest part of my hike, and the hardest to follow. But again, the trail crossed watersheds, and I was facing east again on an even steeper slope, where the trail seemed to be maintained by deer and elk. I’d seen no evidence of humans on this trail, probably not since the summer 2002 wildfire.

The last stretch crossed back to the west, and climbing through dense ferns, entered a young stand of aspens, fir, and spruce. A wide corridor had been cut through these, and a few small peaks rose on my right, but I had no idea if any were the actual summit, so I just kept following the open corridor.

Finally I emerged from the trees, and could see another peak about a quarter mile away across a low saddle. My trail seemed to continue downwards to the east, looking more like an old road. I checked my map, but still wasn’t sure, so I started up the opposing peak, and soon found myself stopped by regrowth and deadfall with no easy way forward. Checking the map again, I became convinced I’d passed the actual summit – it was probably one of those little bumps I’d passed in the forest.

I returned into the corridor through the forest, and eyeballed an easy way up. Sure enough, I soon emerged on a little rocky bump, where a rusty can covered a jar with a record of ascents. I had no interest in that, but just below the bump, a grassy ledge offered a 360 degree view, a view I’d only dreamed about.

Clouds had been forming for the past hour or so, looking like a storm in the north, with wind rising and temperature falling. Now I could see curtains of rain to the north and east. I tried to absorb these views, but was most captivated by the view of the big eastern basin. I became more and more convinced that this was the most beautiful landscape I’d ever found in this area. It was worth walking that long road, just to reach this view!

Returning, I could see rain ahead in the west, and as I emerged from the corridor in the forest, there at 10,000 feet, I was hit by showers blown by a strong wind, and had to dig out my rain poncho.

From the next couple of hours it would rain on and off, with temps in the 60s, occasionally clearing here and there. I’d definitely escaped the heat wave!

After leaving the cabin and rejoining the crest road through the burn scar, I came upon two hawks, soaring together and apart, hovering, diving and briefly grappling mid-air. My views of the landscape were an ever-changing pageant of monsoon weather.

As I left the western watershed and re-entered the eastern for the final segment before the trail junction, it was great to be able to see the southern peak that I’d climbed so many times, from this angle. When descending the back side of that peak I’d been facing this road, but at nine miles it’s just too far to pick out with the naked eye.

It hadn’t been a long hike, nor entailed as much elevation gain as I prefer, but I couldn’t have gone much faster – the unmaintained peak trail made it challenging and slow. The drive up the road had taken two hours, and the hike, with many stops, had taken six-and-a-half. With the two hour drive back home, it turned into a ten-and-a-half hour day.

And the agonizing drive down that road, where I bashed my undercarriage on rocks twice, convinced me that I shouldn’t be doing this anymore. Comparing the way my vehicle drives on rocky roads vs paved highways, I finally realized that the MacPherson struts that make it handle well on pavement, are definitely not designed for off-road use. They have little give, producing a stiff ride, which is just miserable on rocky roads, where I have to drive extra-slow.

This is more pronounced when I see others driving the same roads in more capable vehicles. On this Sunday evening, I was surprised to encounter a young guy driving a pickup with camper shell up the upper part of the road, obviously intending to camp out at the cabin. We met in a rare level clearing with plenty of room to pass, but as he continued, it suddenly dawned on me that if I’d met him at most places on this road I wouldn’t have been able to back up for him without destroying my vehicle. My road clearance is so marginal I need to scope out a precise line to get over these rock ledges, which I wouldn’t be able do in reverse. In some situations I’d be obligated to back up for the other driver, and there are plenty of rednecks around here who would sooner shoot me than give way.

September 4, 2023

Old Reliable

I didn’t feel like driving this Sunday, but the day was forecast to be hot and I wanted to keep working on my conditioning. There was really only one option near town, the eighteen-mile crest hike that utilizes part of the national trail. It’s not wilderness, it’s close enough to town that I often meet casual hikers near the lower and upper trailheads, and cattle occasionally use the upper part, but it allows me to achieve serious mileage and elevation on a reliable trail. And even though it’s not wilderness, it proves how healthy our mountain habitat is in general, compared to public lands near urban areas.

The approach is on a sporadically maintained primitive forest road up a narrow canyon. There were two other vehicles at the trailhead, but the only track I found on the road, and on the upper trail, was from a single mountain bike. The upper trail is so steep and rocky I assumed the biker took the gravel fire road to the crest from the opposite side, and rode down this canyon segment.

The habitat along most of this trail is lush even in a drought, but we’d gotten enough rain recently that wildlife was really thriving. Heading down though dense regrowth past the shoulder of the 9,000 foot summit, I noticed a hummingbird working the flowers ahead and froze where I was. The bird also stopped, to perch on a low branch beside the trail. I waited several minutes, then slowly moved a couple yards closer and froze again. I kept moving closer in stages like this until I was literally only a yard away, and the hummingbird – probably a female broad-tailed – hung in there, staring back at me with what appeared to be curiosity.

That experience was so cool that I kept stopping in flower-dense areas during the rest of the hike, hoping pollinators would ignore me and approach. It generally worked, but I was paying so much attention to what was happening above the trail that I slipped on a rock and tweaked my ankle at one point. My reinforced boots allowed me to keep hiking, but it was swollen and sore the next day.

The lower part of the trail is mostly shaded, but burn scars and scattered clouds along the crest meant that I was moving between hot sun and chilly shade for most of the day.

The last two-and-a-half miles are very seldom used, running just below the crest through wildfire burn scar and remnant forest on a steep and rocky slope. I heard whooping and hollering behind me, and the grinding of tires on gravel, and was glad the mountain bikers were sticking to the fire road.

There’s always at least one hawk working this slope, and today there were three, along with many other birds closer to ground. But finally, I heard tires behind me, and scrambled to find a place to safely get off the trail on this steep slope.

It was a group of three mountain bikers, the first of a convoy of twelve. The leader, the oldest, stopped to placate me, warning about the others to follow and wishing me “peace and tranquillity”. He said they were riding to honor the race which had been cancelled this year – a downhill race where they get a permit to close off one of our most popular trails, and competitors bomb down in full body armor on $10,000 bikes.

The other riders were spread out over a half mile, and from then on I kept having to quickly find a safe place to step off the trail so they could pass. The last group was a duo, and the young female rider lost her balance on a loose rock so I had to wait patiently while she figured out how to get going again.

Riding high on their machines, they were obliviously disrupting all the wildlife I’d been enjoying in my frequent stops. Our natural habitats were just a colorful backdrop for their adrenaline sport.

When I reached the “park”, the shallow natural basin at the end, I stretched out on pine needles in the shade and rested for a full half hour before heading back. The next day, lying on the sofa with an ice pack, I found myself wondering how much longer I can keep doing these punishing marathons!

Eighteen miles is a long hike, even on a good trail, and I was getting pretty sore by the time I reached the shoulder of the peak. That’s an important milestone because it’s all downhill from there.

And by the time I reached the trail crossing four miles from the end, I was limping. I collected some trash left by hikers or bikers during the day, and I finally took a pain pill to get me through the last two miles on the canyon road.

August 28, 2023

Sweaty Canyon

I’d been waiting all summer for the weather to cool off enough so I could hike the canyon trail over in Arizona that had finally been cleared. According to the forecast, it still wouldn’t be cool enough, but we’d been having monsoon weather for past week, and I was hoping I’d have cloud cover, and possibly even rain, in the afternoon, to cool things off.

Over the past four years, I’ve been exploring every trail that climbs from the accessible northeast basin of the range, through the wilderness area to the 9,000 foot crest. Every trail, that is, except this one – so this was now my holy grail.

I’d actually tried it a year and a half ago, and found the final 1.3 mile stretch seriously impassable. But a professional trail crew had finally cleared it this year – twelve years after the 2011 wildfire.

Not only would this complete my exploration of the northern canyons, but it would be the longest hike I’d ever done in this range. What limits me is the distance from home – the long drive means less hours available to hike. So today I would leave early.

About thirty miles south of town, a pronghorn crossed the highway in front of me. Hadn’t seen one for a few years – I took it as a good omen.

Despite the early start, air temperature was already in the 80s when I reached the 5,240 foot trailhead at 8:30 am. And despite our summer-long drought, and the fact that the creek started out bone-dry, I was soaked with sweat and swarmed by flies within the first mile. These northern canyons hold moisture – from our wet winter and a few rains in June – and unlike in our canyons back home, I found an impressive display of wildflowers and pollinators.

One or more bears had preceded me on the trail this morning, leaving scat all the way up. The first stretch is a steady four-mile ramble at a shallow grade, under red cliffs and spires, through riparian forest dominated by sycamore, cypress, ponderosa pine, and oak. The creek was running intermittently, but often choked with algae. I saw no human tracks anywhere – presumably the heat’s been keeping hikers away.

There’s supposed to be an apple tree on the trail about three miles in, but I hadn’t found it before and didn’t find it this time either. The heat combined with humidity were really exhausting and discouraging.

Moving slower than usual due to the heat, I finally reached the junction where the big side canyon comes in from the west. Beyond here, the trail becomes very rocky and very steep, climbing continuously at an average grade of 21% for the next three miles, but it also enters dense mixed-conifer forest that provides more shade. Scattered clouds were forming so I was hopeful for cooling temps.

But it was so muggy, even occasional shade failed to provide relief. I couldn’t remember when I’d been this physically miserable on a hike. The only things that redeemed it for me were the beautiful forest, the rock formations, the flowers and the pollinators.

Finally, after a mile and a half, I reached the end of the forest and the edge of the burn scar. It was taking me much longer than expected, and I hated to think I might fail to reach the crest.

I had to at least confirm that the upper trail was accessible. On my previous attempt, I’d gotten lost in a deeply eroded ravine choked with deadfall and regrowth. The ravine remained a nasty place, but big cairns on each side showed where to cross, and clear tread continued on the opposite side.

This restored trail had already been colonized by annuals, responding to moisture that remained in the soil from last winter. But I quickly learned to just ignore the annuals, striding through them as if they didn’t exist. I could see the narrow drainage above this burn scar, where a band of forest had escaped the fire. That was my next destination – I’d failed to bring a map, but assumed it led straight to the crest.

Cloud cover was now almost complete, and the air temperature was dropping, but I kept sweating just as hard. I was relieved to reach the intact forest, only to discover it led to upper slopes that had been completely cleared by fire. The ground here was white gravel, and as far as the eye can see, it was blanketed with ferns and thorny locust, in some places shoulder-high. The trail showed as only a vague disturbance in the dense vegetation.

In this treeless landscape, that 21% grade felt Sisyphean. From my perspective, I couldn’t tell how near I was to the end – I assumed much of what I was looking at were false peaks. I was pushing my way through waist-high annuals, climbing a seemingly endless series of long switchbacks toward the ever-darkening sky, stopping often to catch my breath.

Here in this alpine burn scar where you could almost touch the clouds, wildflowers were lush and pollinators were working as hard as ever – I even saw hummingbirds.

Finally I was high enough for a view east, but I wasn’t sure what I was looking at. And then it felt like the last switchback was approaching a saddle. My clothes were drenched with sweat and my whole body ached, but I’d reached the crest!

It had taken me 5-1/2 hours to go seven miles, climbing almost 4,000 feet, in tropical humidity. I’d felt a few sprinkles on the last switchback, but that would be it for the day. I was rewarded with a view into a new watershed, but this saddle wasn’t a place to linger. And I had to make much better time on the way back, to reach the cafe, burrito and beer before 6 pm closing.

I expected to be cooler on the way down, but even the effort of descending kept me hot and sweaty. I’d allocated nine hours for the entire hike, and I thought that would leave me plenty of time, so I made plenty of stops, especially enjoying the sight of a couple of beautiful Englemann spruce trees, isolated here in one of their southernmost habitats.

I’d been drinking plenty of water and adding electrolyte supplement, but in the next two miles the leg cramps hit, eventually paralyzing me. I rested, I stretched, I pushed through them, but they took a half hour to subside. And air temperature was rising as I descended.

Suddenly I noticed three apples on the ground beside the trail. Then I looked up – the famous apple tree was right next to me! I never would’ve noticed it if I hadn’t seen the apples on the ground first.

Finally, within the last two miles, I took off my shirt and rinsed both it and my hat in the stream. It didn’t stop me from sweating but it felt better having a shirt soaked with creek water instead of sweat! I arrived at the vehicle with just enough time to change clothes and drive to the cafe right before closing.