Max Carmichael's Blog, page 14

January 30, 2023

Snowy Ridge

Conditions hadn’t changed since last week’s stroll across a basin teeming with pets – our mountains were still blanketed with snow, our trails muddy, our creeks flooded. But I felt ready for a more challenging hike, if I could only find a lower-elevation trail that didn’t cross any major creeks. And preferably something less popular than last week’s pet parade.

I reluctantly settled for the segment of the national trail that climbs from the remote valley northeast of town toward the crest of the range just north of town. I’d hiked that segment in dense fog at the beginning of December, so it would be nice to experience it with good visibility.

Mornings were still below freezing, so I’d be spared the mud until later in the day. On the way up the valley, the landscape reminded me of possible alternatives, so I pulled over and studied the national forest map. It’s huge but doesn’t show enough detail, and I didn’t want to end up on a lengthy detour that would turn out to be a wild goose chase, so I continued to the now-familiar trailhead.

The large campground around the trailhead was blissfully abandoned – I had the day to myself, and savored the initial climb through windy volcanic badlands to the ridgetop.

The next stretch traverses the eastern rim of the long ridge, winding back and forth, in and out of shadowed slopes that held up to 6 inches of snow. The snow was trodden and pitted by a chaotic mix of old and new tracks that I eventually sorted out as a man who had been here yesterday, and a horse and dog that had been here last weekend. Even where untracked, the snow had a soft inch on top of a harder base, but the tracks made for an uneven surface which turned my gait into a sort of lurch.

Birds were active. I’d seen hawks hunting down in the big valley, and flocks of dark-eyed juncos would surround me on the ridge, throughout the day.

This hike averages about 7,200′ elevation, and I was hoping the snow wouldn’t be too deep. But three-and-a-half miles in, the trail crosses to the west side of the ridge, where the patches of snow were up to a foot deep. The man from yesterday had turned back, and I was now alone with the deep holes punched by the horse. And the snow was sometimes soft enough to sink through, so now I was lurching even more. But there were still a few dry stretches of trail, and I stopped in one to put on my gaiters.

With no fog, I could now see how the trail approaches the crest of the range, starting from 7 miles to the north and trending south to within less than 2 miles before turning east to climb around the head of an intervening canyon. From a clearing 3 miles north of the crest, I could even identify the road climbing to the fire lookout, despite my recently impaired vision.

On the second half of the hike I was walking in almost continuous snow, ranging from 6 to 16 inches deep. But this segment of trail is mostly either level or at a gentle grade, so I was making good time and could take it slow where necessary.

I was hoping to go at least 6 miles, and as before, was relieved when I finally reached the ponderosa forest above 7,400′. This rolling plateau of broad meadows and exposed bedrock continues to the edge of a little valley, and past that, begins the climb towards the head of the next canyon. I figured I’d passed the 6-mile mark and didn’t want to have to climb back out of that depression in deep snow, so I stopped and enjoyed the snowy forest for a while before turning back.

Last weekend’s horse and dog tracks continued – I assumed they’d had someone waiting to pick them up at the other end of the trail.

It was a long 6+ miles back, but at least most of it was downhill, and the snow eventually got shallower, to be replaced by mud. I’d timed it just right, completing the one-hour drive home by sunset – with the sun directly in my face so I had to hold one hand up to block the glare.

January 25, 2023

Gifts of Music

All music lovers owe their families and friends a debt of gratitude for the gift of music – not just for introductions to songs or artists, but for the mind-expanding opening of doors onto new genres, and sometimes even unfamiliar cultures.

For musicians, discovering new music has even deeper significance, because it can inspire and even influence our own work.

I’ve been especially blessed because I grew up in a culture which treated music as an indispensable way of life. Even before I formed indelible memories I was immersed in music, and for as long as I can remember I was singing and playing music with my family.

The 1960s music revolution unfolded in the outside world as I progressed from junior high through high school in our small farm town. Until the end of the decade, we only had AM radio, so cutting-edge music could only be found on LP record albums and 45 rpm singles at distant big-city record stores. They couldn’t reach us until someone’s parents drove them there and back, and were either played for groups of us in listening parties or briefly loaned out by the lucky few.

Beginning in the 1970s, my friends and I made and shared cassette copies of our own music and LP records, and that continued over the next three decades, ending in the new millenium when we could burn music CDs on our computers. Schooled in the DIY culture that followed punk rock, we appreciated these cassettes more than the later CDs because cassettes were a little more tangible – they wore our friends’ handwriting and sometimes handmade art, and they had their own dedicated mobile device, the boom box, which had speakers so a room, car, sidewalk, or beach full of friends could all listen.

At this point, the only way I can repay this debt is by paying it forward. Here are just a few of the cultures, genres, and artists gifted to me by family and friends. In most cases I’ve avoided posting live videos of the artists performing, because they’re not available, because the sound quality is poor, or because I want to save them for a later topic.

Delpha & Stella

Maternal grandmother Stella and paternal grandmother Delpha represented my rural Scottish cultural ancestry. Delpha and Stella sang me to sleep with Scottish lullabies, and throughout my early childhood, we met with their large extended families at the Williamson and Carson homeplaces out in the country, for reunions and Sunday sings, all of which featured Appalachian mountain hymns and songs, many of Scottish origin.

Thus it was like coming home when I discovered the Stanley Brothers of Virginia in the mid-1970s. They sang just like my Williamson uncles, with much the same repertoire. “Angel Band” was a song rendered sweetly by Uncle Wib, and “Amazing Grace” was one Stella sang to inspire neighbors in the nursing home before she died.

That old Appalachian music is the first and one of the most important influences on my own work.

After his brother Carter’s death in 1966, Ralph Stanley regularly included a song on each of his albums performed in the ancient style of lined-out hymnody, which was brought to North America by exiles like my Wiliamson, Carson, and Carmichael ancestors in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Joan & Vern

My parents met during the post-war jazz revolution – the birth of bebop – and they were both aspiring musicians, Joan training as a concert pianist and Vern studying violin but jamming on jazz percussion and vocals. I heard so much jazz growing up in the 1950s that it simply became my natural environment, and I didn’t even learn all the names of artists or songs until, in some cases, decades later.

But at the same time, Mom and Dad also loaded our huge hifi sound system with world music and classical music. After they divorced and my brother and I moved to our mom’s hometown, she regularly took us to jazz, classical, and world music concerts in the big city. And after I grew up and left home, my parents avidly followed my music and kept listening and exploring new genres and artists. My dad was listening to Nirvana in his 80s!

I never tried to play jazz, but jazz styles and ideas crept in unconsciously, and I can recognize them occasionally in my work. And today 1950s jazz is one of my favorite listening genres.

My dad was a great whistler and scat artist, and he often whistled “Scotland the Brave”. He gave me one of my first LP record albums, a recording of the Black Watch pipe band. Scottish bagpipe melodies have also occasionally found their way into my work.

Miriam Makeba is the first African artist I ever heard – again, on my parents’ record player.

In parallel with the British Invasion that sparked the 1960s youth music revolution, there was a much quieter invasion from a Portuguese colony – the collaboration between American jazz saxophonist Stan Getz and Brazilian popular music. Despite the stiff competition, Stan’s Brazilian albums stayed in rotation at our house. This was the first international “fusion” music I ever heard, and I followed in Stan’s footsteps two decades later, as I tried to integrate African styles with my Appalachian heritage.

My mom tried to teach me some Bach on her piano, and one of her favorite artists of the 60s, the Swingle Singers, made a career out of jazzing up Bach in a capella. I was obsessed with European classical music in college, and every now and then a classical theme will still pop up in my work.

Mom took me to meet her linguistics professor at Indiana University, who sang old folk and blues songs with his wife, and they introduced me to the Pentangle, a lesser-known but unique British jazz-folk fusion group I still listen to often.

James

I’ve eulogized James elsewhere in Dispatches – one of my principal elders and mentors, leader of a group house in Menlo Park that I shared for little over a year, in 1978-79. But what a productive year! I drew, I painted, I taught myself bluegrass banjo and flatpicked guitar, I wrote stories and songs. And James, an amateur musicologist and passionate social critic, introduced me to the transgressive sounds of the Velvets, the Modern Lovers, and punk rock, all of which became the main inspiration for my work in the next year – not to mention the inspiration for most rock music throughout the following decades.

Mark

Mark is one of my two best friends from high school. We were introduced by my mom because we both wanted to form a band, and we did, and wrote songs together then, sang and played together throughout the 1970s, wrote and recorded together again in 1980, and recorded sporadically throughout the 80s and 90s as a guerrilla music and art duo, the Didactyl Brothers. We’ve always inspired each other in our shared habit of making music, art, and literature with equal passion.

Mark has written and performed both rock and country songs, and we share the love of old-time Appalachian music. But shortly after James introduced me to punk in Menlo Park, Mark was discovering post-punk down south at CalArts. The transition from one to the other was like the blink of an eye, and when I started Terra Incognita in San Francisco in 1981, we were operating in the very loosely-defined post-punk realm. Mark and I listened to Public Image and Joy Division constantly, but you will hear very little of their direct influence in any of my work. I agreed with them that our society was morally bankrupt and needed to collapse, but instead of wallowing in the failure, I wanted to start exploring the alternatives.

Jon

Jon was a founding member of Terra Incognita, a vocalist and percussionist, and one of our leading lights. Culturally voracious, he introduced me to West African music and led or co-produced TI’s ventures into performance art, multi-media cabarets, community-building, and art/science conferences. He arranged the party at our loft which brought together legends of African music for the first time, and triggered my obsession with Nigerian Yoruba music that remains one of my primary influences.

The first African cassette Jon gave me was of the Ramblers Dance Band from Ghana, but I found their highlife style too sweet, so Jon recommended Fela Kuti of Nigeria. I found this album at the legendary Down Home Music in the East Bay, and “Water No Get Enemy” remains my favorite of Fela’s. It may have been an inspiration for the sax I picked up a few months later.

At the same time, Jon gave me a book that heavily referenced the father of juju music, I. K. Dairo. I didn’t actually hear juju until almost two years later on King Sunny Ade’s first international release, but when I did, the genre became my main obsession. I finally saw Dairo in Berkeley in the 90s, shortly before he died.

Jon is also an Asian scholar, and gave me a cassette of this Indonesian gamelan album in the mid-80s. It became a favorite for late-night art sessions at the loft.

Scott

Scott joined Terra Incognita as a bandmate and one of the first loftmates in 1981, playing drums and sometimes experimenting brilliantly on other peoples’ instruments that he was completely unfamiliar with. I’d moved on from Joy Division by then, but Scott showed me that the re-formed New Order had potential – after all, they released what may be the greatest rock song of all time, Joy Division’s “Ceremony”, that summer. Years later, after I’d recovered from my African fixation, I finally embraced New Order’s decades-long repertoire, and it made me want to resume writing rock songs.

Katie

Katie was my life partner, songwriting partner, and bandmate for four years, helping me resurrect Terra Incognita and turn it into a successful performing band. A developing singer and bassist, she was a very sophisticated listener, introducing me to everything from Nina Simone and Kitty Wells to The Raincoats and early REM. But it turned out to be her cassette copies of the Meat Puppets and Holger Czukay, which we listened to over and over, year after year, in the car on road trips, and in the loft during art sessions, that became pillars of my library and inspirations for my later work.

Katie also turned me on to grunge in the early 90s. It inspired a few songs as I revisited rock in my new band Wickiup, and became a staple on mountain-bike rides, but didn’t survive the millenium.

This slow-burning track by dubmeister Czukay includes one of my favorite guitar solos of all time.

Sebastian

The Portuguese artist Sebastian Mendes was only a friend for a short time in the mid-80s, but he had a profound and lasting impact when he gave us a cassette copy of two albums by this English chamber ensemble, because he thought they sounded like our early recordings. It may seem like a stretch, but we did use some of the same instruments – ours were electrified but retained the crispness of their acoustic kin. The Penguins’ composer, Simon Jeffes, was also adventurous and had a sense of humor that TI lacked, and they remain my all-time favorite instrumental group.

Josiah

Josiah was a member of The Invertebrates, an underground San Francisco band that started roughly the same time as Terra Incognita, and in the same place – Club Foot. But we didn’t meet until 1985, when Mark, fiddle player in the reborn Terra Incognita, met Josiah, and our two bands began sharing gigs.

Josiah’s best friend from college, another artist, became one of my best friends, and Josiah became part of our extended family of artists and musicians that persists to this day. He was also writing for a music magazine and passing me cassette compilations from time to time – he made sure that reggae and dub became pillars of my library.

One cassette Josiah gave me in the 90s contained a one-off album by alcoholic Texan Jon Wayne that became my ultimate icon of music that’s so bad it’s brilliant.

Mike

In early 1988, having spent a year recording an album and unsuccessfully trying to pitch it to independent record labels, Katie and I decided we needed new talent and a bigger sound. I put up ads for backing musicians with a “spiritual” dimension, and Mike showed up raring to be our drummer and percussionist. He’d studied under jazz-funk adventurer Ronald Shannon Jackson at Boston’s Berklee College of Music and Woodstock’s Creative Music Studio and he’d briefly worked in New Orleans. But most important to me, he played talking drum and had worked in Ken Okulolo’s band, a Nigerian who played bass on King Sunny Ade’s early international tours.

Mike became one of my best friends while stage-managing our performances and introducing me to an amazing variety of music from around the world, both live and recorded.

Sun Ra is Mike’s guru of spiritual music, but with my grounding in Scottish pipe bands and old-time hymns, Albert Ayler’s spellbinding fusion of jazz, gospel, and military bugle calls struck a deeper chord.

Early on, Mike gave me a tape of pygmy music that I’ve never been able to source anywhere else, calling it the “ultimate music of the world”. I studied it seriously and, bewildered, attempted to reproduce it, and in the process discovered how it was made – spontaneously by everyone in a multigenerational community of hunter-gatherers, based on what they’d learned from animals and their ancestors and added to with their collective creativity.

But even before studying it I agreed with Mike. Pygmy music really is the ultimate music, making modern jazz, and centuries of European classical music, sound like the bumbling of ignorant toddlers. I could never hope to do anything this sophisticated.

Millie

Millie and I became partners two years after the 1989 earthquake that destroyed the Terra Incognita loft and ended the Terra Incognita band. I had realized my dream of establishing a spiritual home in the desert and mastering aboriginal survival skills, and we began exploring remote parts of the Southwest together. She was a talented singer and dancer and wanted to start a band, but mixing music and romance had ended badly for me, so I continued to work alone and she taught herself guitar and started a rock band with a girlfriend.

But like Katie, she was a sophisticated listener, and got me hooked for life on the unique Scottish band Cocteau Twins, which I had ignored in the 80s, along with so much of the developing post-punk scene, as I became obsessed with African music.

A musical friend in the late 80s, saxophonist Benjamin Bossi, had tried to get me interested in Hugo Largo, a newly formed East Coast band that used nearly the same instrumentation as Terra Incognita – electric guitar, bass, and cello. But as usual, I blew him off, and didn’t even give them a listen until 1991, when Millie gave me a cassette of their second album. The lyrics remain some of my favorites 30 years later.

Serge

Shortly after our debut in 1985, the reborn Terra Incognita was recruited for a multi-media extravaganza celebrating the legacy of Julian Beck and the Living Theater. Algerian-born Serge El Beze had been a member and was one of the organizers, so I got to know him first as an experimental theater person. We did more shows together, and I saw him perform music with free jazz pioneer Don Cherry, but with the rise of North African DJs and the international dance scene at the start of the 90s, Serge reinvented himself as Cheb i Sabbah, international music DJ.

From year to year, he migrated between residencies in San Francisco clubs, producing magical nights that were a healthy alternative to the bone-thumping, mind-numbing house music scene. Almost every time I went, I discovered new artists, rushing back to the booth to ask him who it was. I developed a bad habit of dragging new dates to his shows, partly because it was the best dance scene in town, but also partly to impress them with my worldliness. Serge was always friendly and generous in his courtly, gentlemanly, professional manner.

Gnawa music became one of only two genres of African music that I regularly listen to in the desert – the other being Nigerian Yoruba apala, which I discovered on my own.

The kora music of Mali became a staple of “world music” in the 90s, but Kasse Mady earned a permanent place in my library for his loyalty to rural traditions. Like Ralph Stanley, he’s a singer who will send chills up your spine. This piece is more urbanized, but it’s the first track I ever heard from him, the one that sent me back to Serge’s DJ booth to find out who in the world it was.

January 24, 2023

Pet Parade

My headache had been so bad on Saturday, I didn’t expect to hike on Sunday, and turned off my alarm before going to bed. But I woke up feeling good for a change and took a leisurely approach to deciding where to go. I couldn’t do any of my usual hikes because of deep snow, flooded creeks, or deep mud, and exertion was making the headaches worse so I wanted something without a lot of elevation gain. And it was getting too late for a long drive so I also needed something close to town.

I decided to check out a segment of the national divide trail, a little farther south, which I believed would be completely unused this time of year. I’d never been there and wasn’t even sure there would be a recognizable trailhead, but I printed a topo map, bundled up, and headed out into sub-freezing temps under a clear blue sky.

This would be a meandering route through open woodland across a rumpled basin, a maze of low hills and shallow drainages between 6,000′ and 6,400′, trending north toward the small mountain range southwest of town that I’ve climbed over a hundred times in my short midweek hikes. I was starting where the national trail crosses the highway south, and at best, if conditions were really good and my headache didn’t intervene, I might make it the entire 8 miles to the popular trailhead at the foot of the mountains. I knew it wouldn’t be a spectacular hike but I expected to make good time and hoped to achieve more mileage than in all the difficult snow hikes of the past two months.

This segment of trail crosses multiple cattle grazing allotments, encountering gate after gate, and several dirt roads used by ranchers and off-road enthusiasts. I began to notice mountain bike tracks during the first couple of miles, which makes sense, because even competitive mountain bikers seem to do most of their riding on gentle trails.

About two miles in, I heard voices behind me, then a whirring sound, and stepped aside to let a biking couple ride past, followed by their dog. They appeared roughly my age, were overdressed for the weather, and were riding slow, hence the dog had no trouble keeping up. I’d never seen adult mountain bikers ride so slow, and while I was friendly as usual, I was sorry they had to haul these expensive, resource-intensive machines out, further distancing themselves from nature, instead of using the feet they were born with.

I encountered them again, returning, shortly before reaching the graded forest road at the midpoint of my hike. They had stopped to chat with a male hiker, also our age, who was heading up the trail with his dog. We all agreed this trail had suddenly become popular because it remained snow-free and less muddy than others near town. Having caught up with the single guy, I knew I was faster than him, so I continued up the trail, observing to myself that no one can seem to do anything anymore without a dog by their side.

When I reached the graded road I saw the male hiker’s car, a new Honda SUV. On this 8-mile segment of trail, he was only walking 2 or 3 miles total, and the mountain bikers were doing about 8 miles out and back, which is nothing for a bike, but is a decent workout for a dog. This jibes with my experience of dog people. With few exceptions, when you own a dog, your main priority is not to stay fit or experience wild nature. Dog people may say they’re going for a hike, but what they really mean is that they’re obligated to walk the dog(s), ideally for a half hour a day, and they seldom go farther on foot than 2 or 3 miles.

Once past the graded forest road, the trail begins a gentle climb into the foothills of the low mountain range. A mile or so past the road I approached another gate with a middle-aged woman on a horse and two more dogs. The dogs ran to meet me, and the woman waited for me to open the gate for her. She said she was trying to train a “new horse” and it wouldn’t carry her close enough to open the gate from the saddle. Of course getting off the horse would be too much trouble, I thought to myself. But I’m always nice to strangers as long as they’re nice to me.

After letting them through I kept climbing until I came out on a series of broad, heavily grazed grassy ledges overlooking dozens of miles of alluvial landscape to the east, punctuated by low hills and bounded by distant ranges. I’d been diligent about hydrating and realized I was running low on water, despite having plenty of time to reach the next trailhead. I normally bring 3 liters in winter, but had packed only 2 this morning, with the idea of a shorter hike, before deciding on this trail. I hated to turn back now, when I could practically see the trailhead only a mile or so away across the foothills, but dehydration would definitely bring my headache back, so I just went another quarter mile, then reluctantly turned around.

I hadn’t gone too far back before meeting the equestrienne and her entourage of pets. She’d started at the northern trailhead, and like the male hiker I’d met earlier, she was only doing about a 3 mile round-trip. As is typical, I was the only serious trail user among the whole day’s crowd.

Returning, I walked slower and paid more attention to habitat. The maze-like basin south of the foothills was just high enough for a few pinyon, but consisted mostly of open juniper-oak woodland with bunchgrasses, beargrass, and various shrubs in between. I remained frustrated to be unable to do the full distance, but was grateful my headache hadn’t returned. It was an easy hike I wouldn’t be anxious to revisit, but it’s always interesting to see a familiar landscape from a slightly different vantage point.

Two miles from my vehicle I came upon yet another party, a couple my age, this time with two obviously expensive purebred dogs, one a big shaggy wolfhound. They struggled to restrain the dogs as I passed. Like I said, I’m always friendly, but after passing them I’d exhausted my tolerance for pet owners.

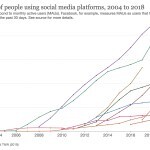

When I was a kid growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, pets were for kids, in affluent or midde class families. Working class families couldn’t afford pets. The lifespan of cats, dogs, and horses is how long it takes humans to become adults, so as you became an adult, you left your pet behind. Childless adults, and parents whose kids had grown up, did not have pets.

In subsequent decades, as capitalism and technology increasingly fragmented human communities and isolated individuals, turning social services into commodities, individuals became lonelier, more vulnerable, in need of companionship their dwindling human relationships couldn’t provide. With the advent of social media in the new millenium, childless, socially isolated adults acquired pets in order to share and get “likes” from distant people called “friends” that they could only interact with digitally.

But social media can’t fully explain the epidemic of pet ownership among adults. Why do most childless adults now own pets, whereas virtually none did when I was a child?

The most common answer I’ve heard is that “I’ve always had one”. But this is simply acknowledging a habit you can’t control, like smoking cigarettes or drinking yourself into a stupor every night. To me, it suggests that in some sense, you never grew up – when you reached the age of adulthood and your childhood pet died, you simply got another one, clinging to that juvenile master-slave relationship with animals.

It’s widely acknowledged that for childless or single adults, pets are acquired as surrogate children or “living plush toys” – something to cuddle since you lack a human companion. The latter clearly shows the infantile nature of much pet ownership.

Mental health authorities commonly claim that pet ownership improves the individual’s mental health. But the anthropocentric and individualistic nature of our culture ensures that these specialists remain ignorant of the broader context, the root causes of social isolation and the ecological and sociological impacts of pet ownership. According to a recent Forbes survey, 78% of pet owners acquired their pets during the COVID pandemic.

Pet owners love to claim that they’re “animal lovers”, when all they really are is pet lovers. On today’s 12-mile hike through mostly wild, native habitat, I encountered 6 people with 7 pets, 840 lbs of humans with 1,230 lbs of pets. These people obviously consider themselves nature lovers, but by taking their pets into nature they reduce their opportunities for encountering wildlife, since their pets either scare wild animals away or actively chase them.

Geographically and ecologically, both humans and their domestic animals displace wildlife, taking resources away from wildlife, damaging and destroying native habitats and hastening the extinction of wild species. I’m sure all the trail users I encountered consider themselves conservationists or even environmentalists, but in reality, as a group, they’re increasing their consumption of natural resources by 150% through the practice of pet ownership.

Most of the world is inhabited by poor people who can’t take proper care of their pets. Dogs and cats roam semi-wild, eating garbage and human feces. But the U.S. is also failing to control its pets. According to some sources, the U.S. has about 60 million indoor cats and 70 million feral cats. Almost 80 million dogs and over 9 million equines, 300,000 of which are feral. On a societal level, pet ownership is clearly ecologically irresponsible.

The devastation of pet ownership isn’t just ecological, it’s also social. Affluent pet owners live in social bubbles where everyone has the luxury to observe the social compact. Cats don’t kill songbirds, dogs don’t bark or chase strangers. But it’s very different in working-class communities like mine. Working-class families now own pets, but can’t take responsibility for them. Cats and dogs run wild through neighborhoods, the nights are a cacophony of barks and sirens.

And it’s not completely true that affluent pet owners observe the social compact. The pet industry has trained affluent consumers to favor so-called “rescue” animals – a marketing euphemism for shelter animals, which is in turn a marketing euphemism for strays. These animals are largely untrainable, so now, their affluent owners increasingly enable their anti-social behavior.

When I encounter old friends I haven’t seen in years, I want to hug them. But if they’re a dog owner, the untrained rescue dog always precedes them – to me, it’s like they’re thrusting their animal at me. Instead of my friends reaching to hug me, the first thing I get is their dog jumping at my chest, soiling my clothes. Would you let your child kick a friend in the chest?

January 16, 2023

Snow Mistake

2023 was not starting well for me. I’d had to skip my New Year’s Day hike due to the onset of an episode of severe back pain. And less than a week later, I developed a headache that became continuous, accompanied by deterioration in vision. The previous episode of back pain, last May, had led to the mystery illness – also with headache – that sent me to the hospital for three weeks.

On the plus side, there was no eye pain – the original symptom of the mystery illness – and no fever, which is what had sent me to the hospital. A headache specialist at our local urgent care clinic refused to give me pain medication because it could mask the underlying condition, but while I waited for a brain scan, she could offer a muscle relaxer, which might or might not help.

Ironically, I woke up with eye pain the following night – but it was gone the next morning. And still no fever. The muscle relaxer seemed to be helping, and I added the last of my back pain meds for a relatively pleasant day. By Sunday morning both headache and back pain were at level 2 or below. I hadn’t planned on a hike, but my body was desperate for exercise.

The weather forecast was confusing. A National Weather Service warning for the entire region predicted dangerous winds up to 70 mph, with fallen trees and property damage. And here I was with my neighbor’s 80 foot tall elm overhanging my house. But that forecast was for the whole of our topographically complex region, and local forecasts only predicted gusts up to 40 mph, peaking in late afternoon. Plus rain beginning before noon and turning to snow in the evening.

Complicating my decision further, a strength workout on Friday afternoon had made my headache worse, so it was likely that a strenuous hike would do the same.

The known side effects of muscle relaxers include dizziness, clumsiness, confusion, and reduced cognitive capacity. So I was not at my best when I decided to go for a shorter hike near town. It was one of the steepest, and would take me onto the crest at 9,000 feet, where I should have expected at least foot-deep snow. But most other hikes would involve mud, which I figured would be even worse.

How long would I be gone? Would I return to find my house destroyed by a fallen tree? I moved the vulnerable stuff to the opposite end, just in case, and hit the road.

It was already snowing lightly. In my reduced mental state, I’d forgotten that temperatures in the narrow, dark canyon around the trailhead were always much lower than in town, despite being only a few hundred feet higher. There was snow and ice on the mountain road and deep snow even on the south slopes above. I made a snap decision to take the ridge trail instead of the peak trail, since the peak trail is one of my regular midweek hikes. In my confused state, I was forgetting that the ridge trail traverses a steep north slope that holds some of the deepest snow in our region until spring.

So it was another gaiter day. I encountered up to 6 inches on the lower part of the climb, but that was doable. A big man had been up the trail before me, and subsequent melting and freezing had left a crust and solidified his tracks, followed by a couple more inches of powder, so it was the worst possible surface to walk on. He’d also had an older crust to walk on, so some of his tracks were near the surface, while others were deep holes where he’d sunk in. And the new powder made it impossible for me to anticipate whether my next step would land on hard crust or sink into a deep hole. I literally lurched and stumbled up the mountain and across the north slope, where the snow was now up to 14 inches deep.

I tried to go slow to minimize the impact on my headache, but I could feel it coming gradually back. It was still pretty minimal compared to other sensations, like cold face, fingers, and toes, so I kept going, determined to go at least as far as the previous hiker.

The day’s storm hadn’t actually made it here yet, but the wind was rising and the dark storm clouds were racing out of the west and over my head. What the hell was I doing up here?

This is a trail that used to be one of my favorites, but became totally overgrown and virtually impassable after a 2021 wildfire that burned around the entire ridge. I used to take it to the stock pond at the end of the ridge, a little over 6 miles one-way, with about 2,500′ of accumulated elevation gain. I didn’t expect to get nearly that far today, and the way things were going, I would be lucky to get to the first milestone, a rocky shoulder about 2-1/2 miles in.

But I did reach the shoulder, after 2-1/2 hours of slogging and stumbling through deep snow. The previous hiker’s tracks continued past that point, but I’d lost my competitive drive. And as I turned back, the storm hit the north side of the ridge, and on my return, I faced gale force wind driving snow in my face. The snow turned into a blizzard by the time I began my final descent. And something weird started happening to my boots.

There were patches with little or no snow on the descent, and whenever I walked over one of them, a ball of snow and pine needles developed under the arch of each boot. I stopped to knock them off on rocks, but as soon as I resumed walking, the snowball returned. I eventually found it was easier to keep walking (awkwardly) on the snowballs, because they would fall off by themselves when I hit the next patch of deep snow.

These snowballs got worse the farther down I got, because the snow gradually became thinner and I had to cross longer stretches of bare ground. I had to grab a stick before getting in the vehicle, so I could poke off the final snowballs before swinging my feet inside. That’s when I discovered a kernel of solid ice balled up on the synthetic cords that secure the gaiters to my boots.

I hit heavy rain as I approached town, but the tree and my house were still standing. And we never actually got high winds in town – the most we got was a gentle breeze. Fortunately my headache was manageable, and I took another muscle relaxer along with the maximum dose of acetaminophen to help me sleep.

Online forums showed that the gaiter snowball is a familiar phenomenon. I’d worn these gaiters in snow over a dozen times so far and had never encountered it – apparently conditions have to be just right, with light snow over wet, unfrozen ground. Others have succeeded in preventing the snowball by coating their straps with oil or wax.

January 9, 2023

Crossing Icewater

Severe back pain had forced me to skip last Sunday’s hike, so I was eager to make up for it. But we’d also had more snow, and I knew the high elevations would have from one to two feet. In addition, warming temperatures would be adding a lot of snowmelt to the creeks, making crossings difficult or impossible.

I decided to return to my old favorite on the west side, the hike that crosses a canyon and a plateau before dropping into the second, bigger canyon. It tops out at about 7,200′, so any snow that hadn’t already melted should be manageable.

I knew the long ranch road up the mesa would be slow, with deep ruts, mud, and puddles in low spots. When it’s dry and graded you can get up to 50mph, but in winter or the monsoon it can be undriveable without 4WD. As I headed up in early morning the mud was mostly frozen, but it was the roughest and slowest I’d ever seen.

Still, the snow-covered crest of the range, ahead, drew me forward.

Approaching the trailhead, I spotted something red through the branches of a juniper, and a pickup truck appeared, with a tall guy loading some gear in the back. I got out and wished him a good morning while shouldering my pack. It was warm in the sun but I knew the canyon bottom would be shaded and below freezing, so I was wearing thermal bottoms and kept my storm shell on.

According to the trail log no one had been here for more than two weeks. Most visitors only venture a little over a mile to the first creek crossing. A few try the canyon trail beyond that, and even fewer continue up the switchbacks like I do.

On the way down into the first canyon I could hear the creek roaring, far below, but the sound of water is exaggerated in canyons, so I didn’t worry until I got a glimpse down into a bend, and involuntarily exclaimed. It looked flooded.

I always stop a half mile in to stretch, using that first half mile as a warmup. That’s where the other hiker caught up with me. He was in his early 20s and loaded for backpacking. I asked and he said he was planning to be out 3 or 4 nights, and as I guessed, he was headed for the big creek, the third canyon along this trail. We chatted a bit but he was anxious to move on.

Shortly after that, I got overheated and had to pack up my jacket.

When I reached the crossing, it was higher than I’d ever seen it – at least a foot deep, too high for my boots. But a trail crew had built a dam upstream, with flat rocks the ice-cold water was rushing over – a sort of submerged walkway for hikers. Without that, I would’ve had to give up on this hike.

When researching my waterproof boots and gaiters, I’d read a review by a hunting guide who said they’d kept his feet dry after months of running through creeks. I couldn’t run across this creek – it was at least 12 feet wide and the bottom was lined with big loose rocks. But I’d find out how good my gear was at keeping my feet dry across that dam.

The rock dam was loose and precarious, but steadying myself with a couple of sticks from along the bank, I made it across. The current had driven the water inside the gaiters and about 5 inches up my boots – another couple inches and they would’ve been swamped. But my feet remained dry inside.

It was really cold in that dark canyon bottom, but I knew climbing the switchbacks would warm me up and dry out my boots.

Past the crossing there’s a branch trail that goes up the canyon, requiring many more creek crossings. Continuing on the main trail I followed the young backpacker’s tracks onto the switchbacks, noticing another large footprint that was over a week old. The climb to the plateau is in two main parts – the switchbacks out of the first canyon that gain about a thousand feet, then beyond the ridgetop, the very steep, rocky section that climbs the remaining 400′ to the little peak at the western edge of the plateau. That’s where I found the first snow, and the backpacker’s tracks disappeared.

What the hell? I backtracked and tried to find where he’d turned off, but the ground was too rocky to hold sign. So I continued onto untracked snow, and wondered what he was up to. There’s really no place to go from that peak, other than on the trail. It’s atop a band of rimrock, the uppermost of several layers that continue all the way down to the third canyon. If he was trying a shortcut to the third canyon, he’d have to circumvent cliffs a hundred feet tall, ending up stuck in a maze of box canyons and brush all day, and be lucky to even reach the creek by nightfall, with the trail another mile or two upstream past several more flooded crossings.

Crossing the plateau in the sun, I had to stop yet again to take off my thermal bottoms, and eventually my sweater. I saw the two-week-old footprint there in thawing patches of dirt, but by the time I’d crossed the valley at the east end of the plateau and climbed to the saddle above the second canyon, his footprints had disappeared. I was the first hiker in a long time to enter that second canyon, and as expected, the initial descent held the deepest snow I would find all day, so I had to put my gaiters back on. This was turning into a day with a lot of stops!

Despite the initial snow, the steep descent went quickly. I kept my gaiters on because I was hoping to use them to cross the next creek. But I should’ve known better.

The second creek drains a much bigger watershed, and was running at twice the volume of the first creek. I scouted upstream, where it gets rockier, but couldn’t find anyplace to cross without swamping at least one boot in ice-cold water.

Still, it was great to see and hear so much snowmelt barreling down! I climbed back up the bank and continued on the canyon trail, hoping to find a way across at the next crossing, a half mile upstream. But of course that was just as flooded.

Despite being stopped by the second creek, I was feeling pretty good. It was a beautiful day. I’d had to stop so many times, I wasn’t even trying to push myself – I was just enjoying my remote, wild surroundings. I wasn’t even daunted by the long, difficult climb back out of the canyon – I would just take it easy.

And a few hundred feet above the floodplain, I was relieved to meet the backpacker on his way down. “Where the hell did you go?” I exclaimed.

He laughed, looking a little embarrassed. “I just stopped on that little peak, to hang out for a while.” I cautioned him about the flooded creek, but he said he had sandals and didn’t mind getting wet. Again, he seemed anxious to keep going.

I continued to wonder why he would start a backpack by stopping for three hours, only two miles in. But when I reached that peak myself, and my phone suddenly registered a voicemail, I realized that he’d probably stopped because that was the only place in the area where he had a signal. He was probably doing business on his phone, or catching up with his girlfriend.

His nonchalance about crossing ice-cold creeks up to his knees was what really made me think. I realized that with my Reynaud’s syndrome I’ve become paranoid about getting my fingers and toes wet in cold weather. But my problem with creek crossings goes back farther, because with my chronic foot inflammation, I can no longer go barefoot, and need to use custom orthotics at all times. And sandals and water shoes are not made to accomodate orthotics.

I thought back to the primitive skills course I’d taken in my late 30s. We students all wore serious hiking boots on that 2-week backpack covering about 120 miles, but the three young instructors all wore sandals the whole time, while walking farther and carrying much more weight than we did. Ben, the youngest, wore flat leather “Jesus sandals” with no arch support, and I tried to emulate him afterward. That may have been what injured my foot to begin with and set off this condition.

Cody, another intern on that course, went on to become a prominent aboriginal skills instructor, and became famous for trekking all over northern Arizona, all year ’round, in a t-shirt, shorts, and bare feet. You people whose feet remain strong, and who can endure river crossings in snowmelt, don’t know how lucky you are!

That young backpacker became the hero of my day, setting out in January, embracing multiple crossings of the third snowmelt creek, which would be four times as big as the first. I wished I could do that, and gave serious thought to the waterproof, insulated socks that are now available. Surely my foot could tolerate short episodes in sandals with good arch support. Sure, it would mean a lot slower hikes, with all the changes of footwear and drying out of gear, but I might get over my fear of cold water.

My back pain had been on the edge of triggering all day – I’d had to maintain perfect posture, squatting instead of bending at the waist, being scrupulously mindful of the angle of my lower spine. And when I reached that little peak and began descending from the plateau, I developed a sharp pain in my right knee. It was the same knee I’d had trouble with a couple months ago, but this was different pain, probably sciatica from my back episode. I strapped on my knee brace, but that barely helped so I took a pain pill.

I could handle gentle slopes, but at every steep section I cried out involuntarily. I had to go really slow and keep my leg as stiff as possible. I was not looking forward to the creek crossing, but needed to get there before dark, and the sun was definitely setting.

Finally I reached the frigid canyon bottom and the creek crossing, which was even more flooded from the day’s snowmelt. To prepare for the possibility of slipping and falling in the water, I packed my warmest clothes and camera in a plastic bag inside my pack. I pulled on my lined Goretex ski gloves and gripped two stout sticks, and crossed the flooded rock dam with no problems.

But my problems weren’t over. Starting up the rocky trail, I simultaneously developed cramps in my left foot, right quad, and left hamstring, and it was all I could do to keep from falling over. After the cramps subsided a little, I dug a packet of electrolyte supplement out of my pack and mixed it with the last of my drinking water.

My knees were really tired at this point and I couldn’t keep the sharp pain from being triggered, even on this ascent, so from time to time I cried out involuntarily – it was like someone was pounding a nail into my knee. What a mess!

But the pain meds were doing their job – the pain had moved into my backbrain, and my forebrain believed it had been a wonderful hike. It was dark by the time I reached the vehicle, and I had to drive slow all the way down the chewed up mud of the ranch road.

I stopped at one point to retrieve a spare water bottle, and when I got out of the vehicle both legs cramped up again. What a day! After waiting another five or ten minutes for the cramps to subside, I finished off my water, resumed driving, got up to 40 mph, and then suddenly there were two huge cows right in front of me in the road. I slammed on the brakes, went into a skid, and they finally reacted, heaving awkwardly out of the way at the last minute in typical cow fashion.

Sound of first creek from about 700′ above:

https://maxcarmichael.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/MVI_1564.mp4December 26, 2022

In Search of a View

I should’ve been all hiked out. I’d walked 28 miles and climbed almost 9,000 vertical feet in the past week.

But it was Sunday, and if I didn’t hike, I’d probably just lie around reading a book I’d already read multiple times.

And it was Christmas – I should have been with my family. I thought about dropping in on my neighbors, but they had families too, and small houses that were even less set up for entertaining than mine. I didn’t want to put them in an awkward position.

Looking at the map of our local wilderness area, I suddenly had a brainstorm. I’d learned in the past year that there were dramatic canyons tucked away in the north part. You can reach them either from the far north, which is a four hour drive from town, or from the center, which is an hour and a half away. I found a trail from the center that should either take me into one of those canyons, or along the rim, in only about 4 miles one-way.

By the time I figured that out, it was pretty late. But it would likely be a short hike, so I hit the road.

Unfortunately, on the way out of town I immediately found myself behind a couple of bloated minivans from Texas. They turned out to be sightseers traveling together, driving well below the speed limit, and it’s a two-lane mountain road with hairpin turns and no opportunity for passing. Every time we passed a turnout, I prayed for them to pull over and let me pass. But they never did. They held me up for an hour and fifteen minutes until we all reached the big scenic overlook, where they finally pulled off to take pictures and I got back up to normal speed.

I’ve avoided trails in the center of the wilderness because it’s strictly lower elevation pinyon-juniper-oak habitat, and the Forest Service and Park Service have designated that area as the focal point for tourism. People flock there from all over the world, which is exactly what I try to avoid. Plus, it’s where the three forks of our famous river meet, and the main trails involve dozens of river crossings, which is no fun in winter. But the center is where the most trail maintenance has occurred, so the trails there tend to be in the best condition.

As expected there were already several vehicles at the trailhead when I got there, despite it being Christmas Day. But what bothered me the most was the condition of the trail I’d picked. It turned out to be an equestrian highway, and their hooves had churned it into a mud bog. It was still partly frozen at 11am, but it was forecast to be warmer, and I knew it would all melt by the time I headed back in afternoon.

This is the kind of trail I normally find boring – a very gradual ascent north through grassy meadows and open woodland to a low saddle. From the saddle, it descends into the canyon of the middle fork of the river, which is heavily forested, primarily with tall ponderosa pine. But just before the saddle is a junction where the “rim” trail takes off to the west.

My tentative plan was to go west along the rim, hoping for a view of the canyon from above. The problem with canyon trails here is that you’re mostly buried under the riparian canopy and can’t see the spectacular cliffs and rock formations above you.

But just east of the saddle I could see a point where I might get my first view over the canyon, so I clambered over there.

The view wasn’t very enlightening, since the dramatic part of the canyon was hidden behind a butte. But I did have a perspective west on where the rim trail would take me.

So I went back to the junction and headed west. This was immediately a better trail – narrow, traveled only by wildlife. The map showed a shortcut that bypassed some of the first trail along the ascending ridgetop, and I found its outlet and decided to try it on my return.

This rim trail wasn’t intended as a rim trail – these are not sheer-walled canyons cut through flat plateaus like the ones in northern Arizona and Utah. This trail simply traverses upper slopes on its way to junctions with other trails, farther west. Gullies in those slopes take it in and out and up and down along the way, always through forest, so I never got a satisfying view of the canyon – only tantalizing glimpses through the trees, of white pinnacles and strangely fluted cliffs. There were some nice red capstone bluffs above me, and some cool white ones across the canyon in the distance, but no trails go there.

Keeping in mind my late start and the stressful drive back on that mountain road, I was watching the time. I figured I had about 4-1/2 hours to hike if I wanted to get back before dark. But I’d gone slowly and made a lot of stops and sidetracks, so I kept going until I had less than 2 hours left. Thinking of the unexpectedly slow progress I’d made last week in Arizona, I guessed I’d only gone between 3 and 4 miles so far and should get back to the vehicle with plenty of driving time.

With the trail in good shape and no serious climbs, I was back to the “shortcut” in no time. I followed what looked more like a game trail down the narrow ridgetop, but it eventually disappeared. The ridge got steeper and steeper, but never reconnected with the main trail. Eventually I reached the edge of a bluff, and could see no sign of the trail below. Was I even on the right ridge? I felt totally lost, and turned back to return to the rim trail.

Back on the main trail, just past the junction with the rim trail, I met a young couple, tourists doing a late hike. The man asked me how much farther it was to the end, wondering if they would have enough time to get back before dark. It wasn’t clear what he meant by the “end” – as I said, the trail goes over the saddle and descends to the river, and the total distance is over 4 miles, but he believed it was only 3 miles to the end of the trail. I just said they had more than 2 miles to go to reach the river, and after leaving them, wished I’d clarified there was no way they’d get back before dark.

For my part, I got back with plenty of time. And at home, plotting my route on Caltopo, I discovered that with all the stops and sidetracks, I’d gone almost 10 miles in 5 hours – not too shabby for a hastily-conceived reconnaissance with lots of stops. It was now clear that to get a proper view of that rugged canyon, I’d have to approach it from the north, and that would not be a day trip.

December 23, 2022

Return to Boulder Canyon

Three and a half years ago, I tried to hike this canyon without a map, and ended up mistakenly scrambling up a three-mile-long pile of giant logs and boulders, enticed by pink ribbons that turned out to have nothing to do with the actual trail, and almost losing my mind.

I did reach a spectacular waterfall, but was left with a powerful yearning to come back some day and find a less maddening route all the way up this canyon to the crest of the range. It would be a route that’s unique in taking you from high desert, through Southwest riparian habitat, to alpine fir forest at 9,000′, with massive rock formations and views across the landscape on your way.

One reason I got in trouble in 2019 was that floods had washed out part of the lower trail, and I could find no information on how or whether I could reconnect with the upper part. Being well-watered this canyon is dense with vegetation as well as boulders – it’s a jungle where it’s easy to go astray – and there was no record of anyone using this trail since 2015, two years before the big wildfire that led to the flood damage. It’s a remote and challenging trail that likely never saw much use anyway.

But when planning this trip I revisited the crowd-sourced page for this trail and found that a group had hiked it in September, claiming it had been rebuilt by a trail crew and was now clear and easy to follow.

I’d driven the access road twice before – it’s a very rocky high-clearance-only path roughly bulldozed up the alluvial fan behind the state prison, to the creek crossing, about a mile below the mouth of the canyon. On both previous visits, the creek crossing had been flooded to over a foot deep and blocked by 18″ tall boulders, so I was assuming I’d again have to park at the crossing, find a log to cross the raging creek on, and walk the rest of the way up the old road on the opposite side.

With a perennial stream, this canyon has always been attractive to miners, ranchers, the military, and prison developers. The map shows the dirt road continuing up two miles past the mouth of the canyon, making two more creek crossings in the process. At least two different water pipelines were laid down the canyon in the past – a old buried iron pipe, and an elevated PVC pipe which formerly supplied the prison. But even before the wildfire, floods destroyed both the pipelines and the upper part of the road.

Following the road and trail as shown on the map, from the first creek crossing to the crest road, would be 6-1/2 miles and over 4,000′ of accumulated elevation gain, so I was expecting a long, challenging day, and hit the road over an hour earlier than usual. But when I reached the creek crossing, it was less than 8″ deep and was clear of boulders. So I drove across and continued to just before the mouth of the canyon, where there’s a turnout. Now the hike I was planning would be two miles shorter, round-trip, and I should have plenty of time!

Since the lower part of the trail follows the old road, it’s always interesting to see how drivable that road is, and how far people have made it up recently. With floods, this canyon has regularly been conveying the top of the mountain down from time immemorial, and the top of the mountain surrounds you all the way up, in the form of white boulders that fill the creekbed and have been bulldozed into rows beside the road.

It was below freezing, and even here at 5,500′, little patches of snow hung on in the shadow of boulders. Entering the mouth of the canyon, I was glad I’d parked where I did – what was left of the old road needed higher clearance than I’m comfortable with. But tracks showed that a bigger truck had recently been up here. And someone had been collecting sections of the old PVC pipe and stacking them alongside the road, presumably to haul out at some point. It would be an even more beautiful canyon without the ruins.

I started making noise as soon as I entered the riparian forest, to alert bears. I’d encountered a black bear here on my last visit, and this range is reported to have the highest density of bears in North America.

Before long I came upon a flock of 7 wild turkeys. And a little farther, a boulder I figured would stop even the biggest truck. But no, some macho dude had made it over that, all the way to the next creek crossing, where there’s a graded turnaround, since no vehicle on earth can cross at that point now.

After a little deliberation and searching for sticks, I crossed the roaring creek on a thin, sinuous fallen tree trunk I expected to flip on me at any time and dump me in the ice water. A few dozen yards from the bank, the old road reappeared, rockier than ever. And a few hundred yards up canyon, I came to the third creek crossing, which was both easier and more dangerous.

That third crossing was probably where I got lost before. But on the other side, after climbing over a towering tangle of logs and branches, I found a series of faded pink ribbons which actually led me through a thicket and back to a surviving segment of the old road. From there, it was a straightforward “walk in the forest” until I reached the next flood washout.

I never found this route on my previous attempt, but here, another pink ribbon beckoned me up to the left, where a faint trail bypassed the washout, climbing high up the bank, and back down, to rejoin the next surviving segment of the old road.

Rounding the base of a boulder, I came upon a rock alignment – again, something I hadn’t encountered on my previous visit. The rocks showed a branching of the trail, and a marker post with an arrow directed hikers toward the first waterfall, partway up the opposite side of the canyon. Apparently that’s the destination of most visitors here.

Continuing on the left branch, I reached the original end of the road, at the base of the massive boulder pile. There, two tributaries come together to form the lower creek, and that would be my moment of truth, since that’s where the old trail had been washed out.

Back in 2019, after wasting over an hour scrambling over flood debris in the lower canyon, I had finally relocated the road and reached this point. I hadn’t seen evidence of a trail continuing on this side of the creek, but I saw a pink ribbon in the trees across the base of the boulder pile, so I clambered across and went that way, which led eventually, with utmost difficulty and increasing desperation, to the waterfall.

Now, however, I spent more time scouting, and finally noticed a pink ribbon hanging from a tree, straight up the bank from the washout, and some disturbed ground that might have been a faint game trail. I decided to go up there – it was about a 40% grade – and continuing, found what was obviously a new trail bypassing the old one that had been washed out. It was very narrow and very precarious, climbing 50-60 feet above the creek, skirting the vertical bank in places. But eventually it led to the original trail, which followed the left-hand tributary.

This tributary canyon was narrow, and on the left side, the trail was forced to wind back and forth between big boulders at the base of a cliff. Rounding one huge boulder, I surprised a small troop of coatis. And I finally came upon a small, very old pile of bear scat – the first I’d seen so far. So much for all my noisemaking to warn away bears!

And at last, I came to the final creek crossing, beyond which I hoped to find my trail to the crest.

Since this tributary was smaller than the lower creek, it was easier to cross. But the old trail had been blocked by debris on the other side, and I found another narrow, precarious bypass that again took me 50-60 feet above the creek and involved climbing over deadfall and boulders. It had become obvious that the September hikers had been exaggerating – this trail had hardly been rebuilt, let alone cleared. The best you could say is that an expert can find a route.

Now I was in deep shade, where snow had collected up to 8 inches. But the trail to the crest consists of nearly 40 switchbacks climbing 2,200 vertical feet, and the slope they climb faces west. I figured every other switchback would have enough southern exposure to melt the snow, and I was right. All the way to the top, I only had limited patches of snow to deal with, up to a hundred yards at a time.

But I had more immediate obstacles to get past: deadfall and overgrowth. Far from being rebuilt and cleared, the switchbacks were blocked again and again by deadfall logs and small, tough shrubs. And I began to suspect that the September hikers had lied about coming this way, when I kept finding old rotten trunks and branches blocking the trail that you would normally break or toss aside in order to pass. Removing obstacles is just good manners, to improve the trail for the next visitors.

Eventually, I did find a deadfall log across the trail with a recently broken branch that someone had removed in order to step over it. I concluded that the September hikers preferred to go around obstacles rather than removing them – I guess they figure that’s the job of trail crews. I did my part by breaking branches and hauling small trees off the trail wherever possible.

The switchbacks seemed interminable, and I came to a few spots where tread disappeared completely and I had to scout a route before relocating the trail. But the reward was the view, which got better with each increase in elevation. Finally, on the last switchback, I got the full view south out of the main canyon, and shortly after that, I crossed the crest into the interior of the range. I’d done it – what I’d been dreaming of for years!

Unfortunately, that seemed to be the end. I’d expected to continue up this ridge about another mile, to the crest road, but the trail ended abruptly at a distinctive cairn, with nothing ahead but a maze of deadfall across a steep, overgrown slope.

I scouted and I scouted, finally returning to the cairn in dismay. I checked my map, which showed a tiny dogleg at this point. What if I just went straight up the slope?

That’s what I did – about a hundred feet, climbing over deadfall logs. And finally spotted the continuation of the trail, on the opposite side of yet another couple of deadfall logs.

In short order, that took me to the fairly level top of the ridge, partly forested, holding deeper snow, where I had glimpses of the high peaks of the range, arrayed to north and east.

I knew I’d only gone about 5 miles so far, and it’d taken me 5 hours. I hoped to go faster on the way down, but I was still surprised at how much slower I was hiking on this trip. The guy who created the Arizona hiking website collects all sorts of data – including your average hiking speed – and his average speed is quoted at over 3 miles per hour. I couldn’t believe this, so I looked at his list of recent hikes, and it turns out he typically hikes an average of 5 miles, with an average of 1,000′ of gain – less than I get on my short midweek hikes.

In any event, I was now where I wanted to be – on top of the world. I had no need to go any farther – only to reach the crest road – and I didn’t want to rush on my way back.

Going down those switchbacks was so much easier! I’d achieved my goal of reaching the crest, and despite all the obstacles, I decided the condition of this trail is just right for me, as is. Enough ambiguity, deadfall and overgrowth to make it a challenge without making it a bummer. Yes, I benefited from a few pink ribbons, for which I’m grateful – but they could’ve been put up any time in the past couple of decades. Wild animals are now keeping it open and maintaining tread – no human workers needed.

And in the canyon bottom, I encountered what I assume was the same troop of coatis. This time I could see at least one was a juvenile, and while the others hid, the biggest adult perched on a boulder above and chuffed at me for a while.

One thing I noticed on the way up, but puzzled over on the way down – the soil of the trail in the tributary canyon bottom was “turned” as if with a plow – like walking in mashed potatoes – with frequent deep holes like large hoof prints, but at random, without any identifiable pattern. It was another thing that slowed me down, and I still couldn’t figure out what caused it.

Returning those 5 miles, with many stops, took 3 hours. But at sunset, what should I find at my vehicle, but a big black bull?

Some may remember my past experiences with bulls in the wild – being followed, chased, and charged. But I was tired, and it was getting dark, and my vehicle was right there. Standing behind a barrier of brush, I yelled and clapped my hands, but the bull ignored me. So I emerged in the clearing, and still yelling, walked past the bull to my vehicle. It moved off a little and stood watching to see what I would do. So far, so good!

This was a first for me. I unloaded my gear and got in the Sidekick, while the bull stood like a statue, never making a threatening move. If only they could all be so placid!

December 21, 2022

Lesson in Snow Hiking

I’m on a little road trip to this Arizona mountain range, for better access to trails that are just too far for a day’s drive. But it’s winter, we’ve had our first couple of regional snowstorms, and as usual I was targeting high-elevation trails. The crest of this range lies above 9,000′, topping out over 10,700′. I expected at least a foot of snow on the crest, but with little previous opportunity to test my winter boots and gaiters, I wasn’t sure how the snow would affect my hikes.

On the evening before my first hike, driving into the town that lies at the foot of the north wall of the mountains, I could see that the snowline was well below 7,000′ – on the shaded north side of the range. One of the hikes I was most interested in approached 10,000′ on that north slope.

The hike I really wanted to start with is on the south side, an hour’s drive from town. But in the morning, unforseen difficulties delayed me more than an hour, so I ended up stuck with a closer north slope hike, where I could expect the most snow.

That morning, I reconsidered my options on the north side. I couldn’t find any online trip reports for my first choice – the only info I could find was a reliable source saying the trail was long abandoned and likely impassable. Without snow, I’d be interested in trying it anyway – it climbed a canyon which was reported to be spectacular, very rocky with many waterfalls. But I couldn’t see myself routefinding, bushwhacking, and fighting my way past hundreds of obstacles in deep snow.

Of the remaining options, I ended up aiming for the “National Recreation Trail”, the most famous trail in the range, which starts in the northside canyon, just outside of town, where a terrifying, vertiginous paved road climbs all the way to the crest. The trail starts at a campground just below 6,700′ and switchbacks to a 9,400′ saddle, where it drops steeply towards one of the mountaintop campgrounds which are inaccessible in winter. Depending on my progress in the snow, I planned to turn off at the saddle and take a spur trail nearly a mile farther, to a 10,000′ peak bristling with communications towers and a fire lookout. I normally despise man-made structures on peaks, but at this point it seemed my best opportunity to reach that elevation, for one of the most spectacular views in the range.

On the way up the road, a couple of little Japanese sedans raced past me – the road is closed for winter at the crest, but is plowed to the 7,500′ level where there’s a cluster of vacation cabins. At 6,000′ I encountered solid patches of ice in shady stretches of road, and despite switching into 4WD, found my extreme all-terrain tires had almost no traction on this road with hairpin curves and 700′ dropoffs with no shoulders and no guard rails.

Before the recent era of mega-wildfires, this trail was likely popular and regularly used, despite its over 3,000′ of accumulated elevation gain. But a short distance from the lower trailhead, it dips into a narrow canyon which was washed out and filled with debris after a fire 18 years ago. Very few people made it past that obstacle until a few months ago when the trail was rebuilt by convict labor, and with the absence of a local hiking culture, I figured I would be one of the first up it in almost 20 years.

A few inches of snow covered the campground, which remained in shade, well below freezing. There was a Subaru already parked in what I assumed was the trailhead parking area, and walking back through the campground, I had to avoid vehicle tracks which were solid ice. There was no trailhead marker for this famous trail – I had to search and guess where it casually began, at the back of a group campsite – and as I stopped there to put on my gaiters, a young woman appeared with an off-leash dog, returning down the trail.

Their tracks ended after only a quarter mile, at the previously blocked creek crossing. I wondered if she’d driven all the way up that perilous road just to walk her dog for a few minutes in the snow?

Even before the crossing, I’d encountered snow up to 8 inches deep, and I was still below 7,000′. My chances of reaching 10,000′ didn’t look good. Past the creek I began climbing the switchbacks, where the only tracks were from deer.

I kept hoping for stretches of trail that got enough sunlight to melt the snow, and I did find occasional bare patches that enticed me to keep going. But they were few and far between, and I climbed about a mile and a half through snow that averaged six inches deep before I reached sunny slopes.

This area had been badly burned, and the ground consisted mostly of small boulders. The trail was a shallow trough that collected deeper snow than the surrounding ground, but the surrounding ground was too dense with obstacles to make it worthwhile to go off trail to avoid the snow. So I kept trudging, the snow getting gradually deeper the higher I climbed.

More than halfway up to the crest, the trail crosses out of the first canyon, makes another half dozen switchbacks, and finally begins a long traverse to the saddle at the crest. Up there the geology changes and you encounter spectacular rock formations, and get your first view of the peak with the towers. But virtually all that traverse is shaded north slope where the snow was now at least a foot deep. I’d always wondered what it would be like to walk a long distance in snow that deep. If I’d known what it was like, I wouldn’t have tried it!

I did reach the saddle – it took me more than four hours to go four miles. Now I know – it takes me more than twice as long to climb in snow.

At the saddle, I found the trail to the peak. It was really steep, and the snow was drifted up to 16″ deep. I followed it about 200 yards, to where it crossed a knife-edge ridge and began a short descent before the final climb. I could see that the rest of it was in shade and the snow would just get deeper, but at least I got a view across the crest to the highest peaks.

One consolation I had on the way up was the assumption that the descent would be easier and go much faster. This turned out to be true – I could go much farther without stopping to catch my breath – but I had to be careful too. Like most trails in the Southwest, this was lined with rocks, and every dozen yards or so I stepped on a rock hidden beneath the snow. The sharp ones threw me off balance, and when I stepped on a tilted one, one foot immediately slid out from under me.

The sun was going down when I crossed back into the first canyon, and could see how much farther I had to descend to the creek crossing and the campground. At this point it was obvious that this trail had been built primarily on slopes where the deepest snow would collect. I had really put my snow hiking ability to the test today, and would be likely to reserve hikes like this for snow-free conditions.

But with the end in sight, I started paying more attention to the habitat. These Arizona ranges host very different plant life from our New Mexico mountains, and I always look forward to it.

Back at the vehicle after more than 7 hours of snow hiking, my hips and ankles were worn out from all that instability. This would be a great trail to hike without the snow – the convicts did a great job, and only about 3 logs had fallen across since their work.

It was the eve of the shortest day and the sun was well set as I descended that icy road, lucky to have no one behind pressuring me – although I did pass a Jeep and an SUV on late runs up to their cabins.

December 18, 2022

Snow Practice

This will be a short one. I’m planning some hikes over in Arizona in the coming week, so I didn’t want to drive far or use up a lot of energy today. I picked a segment of the Continental Divide Trail just south of town, starting at just under 6,400′ near the highway and climbing a ridge to a series of modest 8,000′ peaks. I’ve done versions of this hike several times in the past, and I expected quite a bit of snow up there from the past week’s little storm. I thought it might be good practice for Arizona, where I expected even more snow.

The day was forecast to be cloudy, starting in the high 20s and reaching the high 40s. I didn’t expect it to snow. Since the drive was short, I got an earlier start than usual. Low clouds made it a dark day, and I was all bundled up, wearing my old insulated ski gloves.

After climbing through a maze of rocky foothills, the trail reaches the ridgetop and ponderosa pine forest. Approaching the first peak, the trail meets a dirt forest road that services communications towers. In the past, the trail continued up the road to the peak, then dropped to a saddle before climbing to the second peak. But when I reached the road, I discovered that the trail has been re-routed around the peak to the saddle, so I went that way, and that was where I found the most snow, averaging about 6 inches but with drifts up to a foot deep. Another man had climbed up there in the past couple of days, but he’d turned back without reaching the saddle. I continued to the saddle and up to the second peak in virgin powder, and it started snowing pretty good after I reached the second peak.

I generally love being in mountains in snow, and today was no exception. The forest was beautiful, and I found it really exhilarating, especially after more snow started falling. I returned to the saddle and found my own route up to the first peak, and from there, continued down the road to the trail junction. It snowed for about an hour, then the sky tried to clear, but it was snowing again by the time I dropped from the ridge back into the foothills. What a wonderful opportunity!

December 12, 2022

Fantasy in Freefall

As my regional options for long, high-elevation day hikes have shrunk due to post-wildfire deadfall, overgrowth, erosion, and flood damage, my motivation has reached an all-time low. Yes, there are a few favorite trails left – one to the east, two to the west, and three over in Arizona – but I’ve already hiked all of those in the past two months, so to avoid repetition I’m trying hikes that normally wouldn’t challenge or otherwise interest me.

This Sunday’s goal was a trail that branched off of one I’ve hiked before, in the eastern range, following a canyon bottom from 7,000′ to 9,000′. I was planning to explore the crest trail beyond the junction, then return down the other canyon for a loop.