Max Carmichael's Blog, page 15

December 5, 2022

Mystery Spot

By Sunday morning, it’d been raining on and off in town for almost 24 hours, and I assumed the crest of the mountains would be getting even more. The vast majority of trails in our region involve canyon bottoms or major stream crossings, any of which could be flooded. And I was really enjoying listening to the rain outside while staying warm and dry with a roof over my head.

Plus, I was still trying to go easy on my knee, so I needed a trail that didn’t involve long steep climbs. There was really only one option – to try the national trail from the starting point I’d used last week, but in the opposite direction. I was pretty sure it would also be overgrown with cosmos and feature the dreaded volcanic cobbles, but I had no other choice. Really hard to get motivated, but you know me.

On the plus side, it was warmer – in the 40s starting out, expected to reach 60 in town later. But most of the landscape was blanketed by fog.

From the remote westbound highway, the southbound trail winds through a dispersed camping area on a maze of dirt roads. Those roads would be muddy now, so instead of hiking from the highway, I drove through the campground all the way back to where the foot trail started, a little over a mile from the paved highway. This detail would become important later.

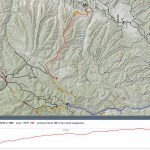

This trail starts at around 6,200′, in ponderosa forest at the base of terraced bluffs of volcanic conglomerate which the rain had stained a dark russet. I had studied the topo map months ago and picked out a vague destination about 8 miles in that should yield me about 2,500′ of elevation gain – but gradually, which would be easy on my knee. I would judge how far I’d gone by the time it took – I generally hike about 2 miles per hour including stops.

Several miles beyond that point, this trail would connect with a trail I’d taken last spring, and a little beyond that, it would connect with the trail that provides the longest hike in my repertoire – 18.3 miles out and back. Together, these converging trails form a sort of tripod intersecting on the crest of our local mountain range, so today’s hike would help fill a gap in my local hikes.

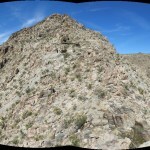

It wasn’t raining when I started out, but the thick fog, drifting slowly in and out of canyons and over ridgelines, limited my view to a hundred yards or less, so I had no idea what kind of landscape I was traversing. But the first mile or so climbed up the conglomerate bluffs, and along the way I got to enjoy some of that exposed rock.

This mountain range tops out at 9,000′ and consists of a maze of forested ridges which all look the same from a distance, so it’s normally my least favorite terrain. But the fog completely transformed it. Foliage, fire-killed tree trunks, soil, gravel, and stone were all saturated, so all the colors were darkened, and again I was walking outdoors in an intimate interior space, enclosed by the fog, with little sense of distance or elevation.

Climbing out of the ponderosa forest, I entered the pinyon-juniper-oak woodland and was immersed in a powerful pine fragrance, like turpentine but sweeter. That fragrance remained with me as long as I was in that habitat – I’ve hiked it for 16 years in all conditions but have never experienced anything like this before.

There was plenty of burr-laden cosmos parviflorus beside the trail, but unlike the eastern segment I’d hiked last week, this part of the trail was clear and easy to follow. And amazingly, it was cobble-free, the ground remaining nice and smooth until the later, higher segment became a little rockier. All in all, one of the easiest trails I’ve hiked in this region. I wasn’t pushing myself, but inevitably made good time.

A little over an hour into the hike, I’d reached the ridge top where the trail leveled out, and a light rain began to fall. My boots were already soaked from wet grass – I’d worn my waterproof boots and pants – and now I pulled on my rain poncho. It would rain lightly from then on, until the last mile of my descent at the end of the day.

Around the same time it started raining, I heard a man yelling, down in a canyon hidden by the fog, somewhere west of me. I figured it must be hunters, but there was no road or trail down there, so they must be on foot.

As expected, my walk continued for miles up ridges through low, open woodland – bathed in that amazing fragrance – with intervals across level, wooded, grassy meadows where the trail was flooded. My nose and cheeks itched from catching invisible strands of spider web that spanned the trail between branches at face height. The fog kept me blind to the landscape around me, and except for a couple of short steeper climbs, it became hard to tell whether I was going up or down at any given time. I was yearning to reach the higher-elevation ponderosa forest, just for some variety.

About 2-1/2 hours in, I did reach ponderosa forest, and the kind of pale, lichen-encrusted exposed bedrock I was familiar with on the crest of the range. And the trail began descending steeply into a hollow, which I didn’t remember from the map. I didn’t feel like I’d gone far enough to reach my planned destination, but this descent definitely wasn’t part of the program.

I continued anyway, crossed a little valley with running water and a faint UTV track, and began climbing again. Very strange. This part of the national forest is not designated wilderness, so I felt lucky not to encounter livestock depredations.

Less than a half mile beyond the hollow, I spotted a sign up ahead, and getting closer, a dirt forest road! I checked my watch – I’d only been hiking 3 hours, including lots of stops – how could I possibly be at the road, which I’d assumed was over 10 miles from the trailhead, and connected the three arms of the tripod? I still felt fresh, like I could keep hiking for miles beyond this point.

I noticed an old Forest Service trail sign that claimed I’d hiked 9-1/2 miles from the highway. 9-1/2 miles in 3 hours! That was much faster than my normal average speed, and I’d been taking it easy all the way. I could only assume it was because the trail was in such good condition. Wow! Now I was really excited. Why not continue to the connecting point with the trail I’d hiked last spring, and make it an even 10 miles? 20 miles out and back would be the longest day hike I’d ever done.

The road was muddy and flooded in places as it wound back and forth between the tall ponderosas. I was looking for a fence that ran alongside and intersected with another fence that was perpendicular, less than a half mile east. But I never found it, and eventually the road I was on started descending steeply off the crest. Where was the other trail? Now I was really confused.

So I returned to the trail I’d come up, and began my descent.

About a mile from the road, I heard a single gunshot – it sounded like a .22 rifle, somewhere west of me, where I knew there was no road or trail. Could it be the same hunters I’d heard, 6 miles or more to the north, bushwhacking on a completely different route from me?

Again, in the fog, I noticed that it was sometimes hard to tell if the trail was climbing or descending. I remembered from the map that this trail climbed over 2,000′, but it neither felt like I’d climbed that far in the morning, nor was descending that much now, in the afternoon. Very strange.

Eventually, I reached the final ridge that descended toward the trailhead. But even there, it felt like I was climbing more often than descending. I thought of the Mystery Spot, a tourist attraction in the California mountains designed to disrupt your senses of gravity and perspective. In the fog, this trail was becoming my mystery spot.

The freshness I’d felt at the top had now completely vanished. My feet were sore, my hip was starting to hurt, and I truly felt like this was the longest hike I’d ever done. The trail seemed to traverse in and out of dozens of side canyons on its way to the end of the ridge, all looking the same.

Finally, as I was about to shut down my feelings and switch into survival mode, I emerged into the final landscape of exposed, russet-colored, terraced conglomerate. Here, the fog had lifted enough for a view of several miles across the landscape. I saw a big canyon to the east, and reaching the end of the ridge, I could see north out over the valley of the highway. I was near the end and could stop to enjoy the view.

I also suddenly remembered that I hadn’t taken the trail from the highway – I’d chopped over a mile off the hike by driving through that campground – so I hadn’t actually gone 10 miles, and couldn’t claim this as my longest hike. Damn! Why did it feel so long anyway? Why was I so sore, and so exhausted, if I’d only gone the kind of distance I’ve been routinely covering for years now, but with even less elevation gain than usual?

It got even worse when I arrived home and checked the maps. My mapping platform contradicted the Forest Service sign I’d found, showing that the distance from highway to forest road is only 8 miles, not the 9-1/2 miles claimed by the old sign. And most discouraging, the forest road I’d reached, and continued east on to find the other trail, was not the road I thought it was. It was several miles short of the road that would “connect the tripod” and close the gap between the three trails.

All in all, instead of hiking 20 miles in a day, I’d hiked less than 14 miles, and only felt like I’d hiked 20. And the elevation gain was less than I’d expected, too. Clearly not a day for the numbers, but on the plus side, I now know the trail’s in good shape, and next year, when the days grow longer, maybe I can return and do the whole thing.

November 27, 2022

Day of the Cosmos

November 21, 2022

Four Eagle Hike

It was time for my first hike in three weeks – after the hiatus of visiting family in the flatlands of a Midwestern city. Before that, I’d blissed out on the exposed rock and forever views of my beloved desert, so now that I was back home in southwestern New Mexico, I wasn’t anxious to bury myself in the forests and thickets of our local mountains.

The views being better on the west side, I decided to head over there and choose a trail while driving.

The temperature was in the low 20s and I had to scrape heavy frost off the windows before starting. A low haze hugged the landscape ahead – probably some effect of the cold. At the end of September, I’d discovered that most of the west side trails had been wiped out by flash floods, and the access road to another had been cut off by the same floods. Now, two months later, I hoped that road would’ve been fixed, so I took a chance and detoured about 16 miles up the dirt mesa road – only to find “Road Closed” and “Impassible” signs at the turnoff.

By the time I got back to the highway, the false start had delayed my day’s hike by an hour. Without much hope of success, I decided to do a “reconnaissance” hike on my old favorite trail, which leads up a canyon to a high saddle with views over the wilderness. I assumed the canyon part of the trail had been damaged by the floods, but at least I would find out how bad it was.

Entering the foothills on the highway, I suddenly saw a half dozen geese wheeling low overhead, on their way south. They looked really big – I’m used to seeing them much higher.

Starting the hike on the traverse into the canyon, I scanned the ridge above, on my left, as a possible alternative if I found the canyon too choked with flood debris. I figured I could return up the traverse and bushwhack up the ridge and see how far I got.

Then, on the final approach to the canyon bottom, a big black bird emerged from the bend below me. A friend has often been skeptical of my bird sightings, correcting me when I’ve misidentified eagles, so I’ve become insecure about bird identification, and reluctant to take pictures of what might be some more humdrum species. This bird wasn’t flying like a vulture, and its coloration wasn’t right for a raven, but I was still slow on the draw and failed to get a pic as it gracefully flapped its way past me.

I continued, and three minutes later another one emerged. This time I knew it had to be a golden eagle, and I was a little quicker with the camera. Two eagles! They must be migrating and had temporarily joined up here.

But after another three minutes, yet another eagle. Three! It was like scheduled flights leaving an airport. I was almost at the creek crossing in the canyon bottom when the fourth eagle emerged from the riparian canopy, following the first three. This one passed within 60′ of me, but wasn’t visible long enough for a photo. This was the third time I’d encountered a convocation of migrating eagles – it’d been at least a decade since the last.

And to my surprise, the canyon bottom, and its creek, showed no evidence of flooding. I wouldn’t need a bushwhacking alternative, but after the false start, I didn’t have enough time to go my usual distance on this trail. I would just hike 5 miles up to the viewpoint on the shoulder of the 9,700′ peak, but that was okay – it would be a “soft” resumption of my broken hiking routine.

Unusually, there had been two other vehicles – pickups – parked at the trailhead. And about 3 miles up the trail in the canyon bottom, I spotted a dog ahead, and then its owner appeared – a backpacker, probably in his 40s. We stopped to talk, and unlike many “outsiders” I’ve met on these trails, he seemed glad to meet me and reluctant to continue his descent. As he revealed his familiarity with the area, I assumed he was local.

He’d spent two nights up on the crest trail, but he wasn’t returning happy. He’d only made it as far as I’ve gotten on a day hike, and was surprised to find I’d gone that far, as he complained about the overgrowth and deadfall he had to fight his way through. He said it was just too much work to be worth it. He said the trail was much worse now than 2 years ago, when he’d gone almost twice as far.

We agreed that in the current wildfire regime, most wilderness trails are simply unmaintainable, and he wasn’t adapting well to the new normal. He said the only way to keep trails open now is with mechanized equipment. Local trail crews had applied for a permit to bring chain saws in the wilderness, but they’d been denied, which he seemed to think was a shame.

I didn’t think it was appropriate to touch on the issue with a frustrated stranger, but afterward I revisited the question of whether human access to wilderness is good or bad. It sits within the larger problem of wilderness itself – an artifical Western concept that denies the cultural nature of pre-conquest habitats. We only preserve wilderness areas because our unsustainable society has degraded or destroyed all other habitats.

What does this mean for trails? Pundits and policymakers claim that access to natural areas encourages people to care about them, and this is lost when trails are abandoned. But the effort and cost of maintaining trails in this new regime are more than we’re willing to invest.

Talking to the backpacker slowed me even more, so I embraced this as a more leisurely hike than usual. The low haze was starting to clear as I reached the crest, but it was still chilly up there, with patches of snow in shady spots. Knowing this trail well, I continued past the crest for another half mile so I could log more mileage and elevation while still ending the hike at a reasonable time.

Unfortunately, on the downhill stretch beyond the saddle, my right knee started hurting, and I remembered the same thing had happened on my last local hike, a month ago in late October. Strangely, I’d had no trouble in the 30 miles of hikes I’d done in our rugged desert mountains. Why did my knee hurt in New Mexico and not in California?

Maybe it was the cold – it is colder here this time of year. But the more I pondered, I thought it might also be the activity itself. Here, I hike on trails that are mostly hard-packed, where I end up pounding my way downhill, which creates repetitive impact on the knees. While in the desert, with no trail, I tend to pick my way cautiously downhill, in random directions dictated by obstacles, and the ground is often loose, absorbing impact.

In any event, I’m going to be even more frustrated now since I’ll need to rest that knee for weeks!

In the meantime, even with knee brace and a pain pill, it was a really painful return to the vehicle.

At least the pain pill put me in a good mood while driving home. And as dusk turned to night, I saw a bright falling star leaving a long trail, directly ahead over the highway.

November 7, 2022

Desert Trip 2022: Day 7

On Tuesday, I actually got up at dawn, long before the sun crested the rim of the basin and warmed the campsite.

I really felt like I was just getting started here, and hated to leave. But I was running out of food and water. I’d brought 15 gallons of water and only had about 3 gallons left – I still can’t explain why. And after breakfast, my food supply was down to cheese, jerky, half a cabbage, a couple days worth of granola, a can of beans, and miscellaneous snacks.

My new rotomolded cooler, one of the highest-rated on the market, still had ice after almost a week. But I’d started with three 5-pound blocks of block ice, occupying about 60% of the interior volume, and had kept it in shade for all but a couple hours on the first day, in temps that never got above 70 and probably averaged less than 55. I was hoping for slower melting – it would presumably be much faster in hot weather, when my old cheap coolers would last up to 4 days.

Long-time readers may have noticed I took fewer pictures than usual. I carry a spare battery and SD card, but was trying to conserve both space and energy by avoiding things I already had good photos of from previous trips. And this is not the most colorful time of year anyway! Still, I ended up with space on the original card, and time to spare on the original battery, after 6 days of shooting.

I apologize to my desert friends that I didn’t see on this trip. You were often in my thoughts, especially as I visited places or experienced things that might interest you! Unfortunately, the only plan I was able to make in advance was my flight to Indiana to visit family. I wasn’t sure until the last minute when I would actually head out to the desert, and then car trouble stranded me in Flagstaff, so even if I had made plans to visit desert friends, I would’ve had to change or cancel enroute.

But to be honest, the main reason I didn’t plan to visit friends in the desert is that I needed to reconnect with my land, and I didn’t know what that would be like. I didn’t want to plan an itinerary because I wanted to be able to follow my heart once I got there. I hadn’t gone camping or backpacking in years, most of my old familiar gear had been replaced, and I was frankly a little apprehensive about the whole experience.

And of course once I got out there, I wouldn’t be able to communicate with anyone – except by climbing to the peak I described on Day 6.

The drive out of the mountains and over to Kingman for lunch was uneventful and unenlightening. One bright spot was not having to stop in Needles – seems like I’ve always been forced to stop there in the past.

The drive went to Hell when I turned south toward Phoenix. I’ve always had problems with Arizona drivers, and that highway, which alternates between 2 and 4 lanes, was a race course for big rigs, monster trucks, and strangely, Tesla Model 3’s. The speed limit was 65, Arizonans wanted to go at least 85, and everyone stuck behind me became enraged.

Ironically, the landscape is beautiful, but I could rarely enjoy it. Excepting the one-hour stop in Kingman, what I’d expected to be, at most, a 7-hour drive turned into 9 hours of stress. Then I had to sort through my gear and pack for the flight, but thanks to Ambien I did get a good night’s sleep!

Thanks for reading. I hope you and your families are all enjoying peace and good health, and I hope we can meet up soon, ideally in our beloved desert mountains!

Desert Trip 2022: Day 6

I woke up on Monday not knowing how or when my trip would end. I only knew I had to reach a hotel at the Phoenix airport by Tuesday night, to catch my flight to Indiana (and family) early Wednesday morning.

The last time I’d talked to my mom, last Wednesday morning, she’d sounded upset that I might be out of touch for almost a week while camping in the desert. Like me, she’s prone to anxiety attacks, and throughout the trip I’d been increasingly worried about her.

I’d been sending pre-recorded text messages from my GPS unit, every day, to reassure her I was okay, but hadn’t briefed her to watch for those, and wasn’t sure she’d even notice the GPS emails among the dozens of junk messages she gets each day.

In addition, during each hike so far, whenever I crested a ridge and had a line of sight for dozens of miles out of the mountains and across the open desert, I turned on my cell phone and searched for a signal to call her, but could never connect with a tower.

By Monday, I could easily imagine her having a panic attack and calling on my friends to come out and find me. So I was worried about staying another day without being able to reassure her. But I was so happy to be here, and felt like I was only just settling in and getting started – I couldn’t remember any time in the past decade when I’d felt so at home on my land. I would really hate to leave a day early.

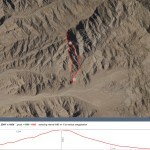

From our campsite on the ledge above the big wash, I gazed up at the peak looming to the north, where an ambitious but failed mine perches on a dizzying precipice just below the summit. The hike to that mine, which I’ve done many times both solo and with friends, is one of the most challenging hikes in the range, but the peak above it is the only place where I was sure I could get a signal on my phone to call and reassure my mom.

My imagined need to justify staying out here another day led me to completely ignore the difficulty and danger of that climb. When I decided to do it, packed and started off on the hike, I was only thinking of a quick out-and-back that would leave my afternoon free. I was in complete denial that it would be the scariest, hardest, and longest hike of the entire trip, with the sole purpose of making a phone call that turned out to be unnecessary.

The peak stands almost 2,000′ above camp, but you can’t see it or the mine from below, since massive rock outcrops rise between. The peak itself is only a mile and a half away in horizontal distance, making for a 25% average grade – which is pretty extreme in itself, far steeper than any of the hikes I do back home.

However, the lower half of the climb is misleadingly straightforward, on a gentler grade traversing bare ground between shrubs and smaller outcrops. Back in the early 90s when I was romping all over these mountains like a bighorn sheep, I would look at a distant peak and say “It’ll take me only an hour to get there”, and I was usually correct. Now, I couldn’t remember my estimate for this peak – fanciful numbers between 45 and 90 minutes were bouncing around in my head.

One ascent with friends, about 25 years ago, had gone bad because my partner’s girlfriend, who was in good shape but was afraid of heights, was having a major meltdown by the time we reached the mine. She had to be coached all the way down, step by step, in abject terror and hating us both for taking her up there. And on one of my more recent ascents, I’d tried a different route that turned out to be even harder, and fell and cut myself pretty bad on a rock coming down.

Today, it was at that halfway point that I realized my mistake. This was going to be a long, tough one. But there was no turning back, and at least I wouldn’t be taking the same route on the way down – I planned to cross the ridge below the mine and drop into the next drainage east, to check the seep above the shade house where I’d lived back in 1992.

The upper half of the climb to the mine involves finding your way around and over ramparts of granite that block the way forward, using bouldering moves that were made more dangerous by my heavy old pack, which has no waist strap and swings back and forth, threatening to throw me off balance – another example of my bullheaded commitment to old-fashioned, low-tech gear.

Getting past those stone ramparts gets harder and harder the higher you get, until the last one, which forces you to climb to the top of the outcrop overlooking the mine works, and then downclimb the north face, using more bouldering moves. On each of those successive ramparts I’d found scat from groups of bighorn sheep – mostly rams, I’m assuming, because that’s what I’ve seen up here before – but it was all months old, at least. In fact, I’d seen lots of old sheep scat on every slope, ridge, or saddle I’d been to so far, here around the rim of our interior basin on the west side of the range.

Well below the main works of the mine I came upon a graded ledge containing bed frames and springs for 5 people – a feature I’d completely forgotten. That, in addition to the collapsed hexagonal cabin above, would’ve hosted up to 9 workers at a time, on a knife-edge ridge exposed to the most brutal winds in the range – but also with the most spectacular views.

Taking a quick look around the mine works – nothing had changed since my last visit, in 2011 – I was reminded of some recent comments by a friend who knows these mountains much better than I do. He also knows and respects my interest in native cultures and prehistoric sites, and questioned why we’d bought this property in the first place, since it’s been so torn up and abused by Anglo mine works, ruins, and trash.

My co-owner, on the other hand, has long been interested in Western (colonial) history, including mining, and views this place as an open-air museum.

My own take is that – apart from these being the only large intact parcels of private land on this side of the mountains – it’s also the perfect base and point of access for nearly 50 square miles of wild habitat, for the prehistoric cultural sites that surround our basin, and for the plateau, the heart of the range. And although I could easily do without all the mining stuff, the broader history of our species shows that these ruins and this junk can provide valuable resources for a resourceful subsistence community, sometime in the unknown future after our own culturally bankrupt society fades away and the regional climate becomes salubrious again.

I’d only been past the mine to the actual peak once before, in March 1990, and I’d completely forgotten both the route and the configuration of the peak itself, which is a quarter mile beyond the mine and 300 vertical feet above. It’s a beautiful, completely wild, grassy little plateau, tilted westward, where you can completely ignore the mining junk below and revel in the 360 degree view, blocked only in the north, across another long canyon, by the north wall of the range.

There, I got my first cell phone signal in the past 5 days, and spoke to my mom, who, as it turned out, wasn’t worried at all.

I hated to leave that place, but the 1-1/2 mile climb had taken 3 hours, and I had to start back down – both to ensure a warm shower, and because I was dreading the descent. On the last climb to the mine, I was with a friend who knew of a partial trail down the eastern slope, past the mine tailings, into the drainage that led to our seep.

Holding onto an old water pipe, I made it past the tailings, to the upper stage of the old cable tramway they used to lower ore into the side canyon beyond, but could see no clear trail from there. There was only a faint suggestion that I began to follow, but it continued only as far as the next little saddle on the outlying ridge between this and the next drainage. Below that, there might’ve been a switchback, so I kept going, but any sign of a trail completely disappeared, and I couldn’t spot anything else on the surrounding slopes. So I began picking my way down this dangerous slope of loose rock, as carefully as I possibly could, aiming for what I thought was the outcrop of metamorphic rock surrounding the seep, far below.

As expected, it was a nerve-wracking descent. I remembered making it on acid, back in the early 90s, after dosing at the mine and having a total freakout when I contemplated this slope from above. The way I prepared myself then was by imagining I was a mountain sheep, clenching the ball of my foot with each step for better traction. Whether real or imagined, it worked back then, but the boots I wear now are far too stiff for that.

Crossing back and forth over the continuously steep and narrow drainage to the seep, to avoid sheer pouroffs and rock walls – sometimes on the surrounding slopes and sometimes in the boulder-choked dry streambed itself – I slowly and carefully made it past what I’d originally thought to be the seep, and finally to the cleft of the seep, whose dammed-up tank amazingly held water – the only standing water I’d seen yet within our watershed of almost 50 square miles. But the seep itself looked completely dry, and there were no bees using it.

The descent of less than a mile had taken almost three more hours, and I could forget that warm shower, but reaching this point, from which I had a clear and relatively easy route back to camp, was a huge relief.

Following the old water pipe to the shade house, I briefly checked it out. Someone had been here and left an empty pop bottle since my last visit, moving the old box springs under the roof, but everything was otherwise intact.

I found the old road to the shade house completely undriveable without major work – a boulder weighing several hundred pounds has fallen into the lower part, and all the steep sections have additional erosion.

My last night in the mountains was bittersweet. I built a tiny fire with the last of my catclaw, ate the last of my leftovers and drank the last of my beer, but I found myself compulsively walking away from both the fire and the lantern, to let my eyes adjust and experience the land in its natural state.

The strap from my sleep screen that secures it under my bedding had torn off the night before, so I tried to do without it at first, but the mosquitos were persistent again and I had to fit the screen around me as best I could. I really wished I could keep sleeping out there under the stars for the rest of my life.

November 6, 2022

Desert Trip 2022: Day 5

Again, I found myself lying in bed after dawn, waiting for the sun to rise above the eastern ridge and warm me up. Meanwhile, I watched the mosquitos desperately trying to reach me through the screen. I got to know them individually, and finally, the most active one suddenly appeared inside! It had apparently found a gap under the screen’s edge. Now I had to get up.

As forecast earlier in the week, clouds had appeared before dawn, but they cleared as I had breakfast and got ready for the next adventure. After hiking northeast on the first day, and east on the second and third, today I would go southeast. First, up to Blockhead – the monolith on the southeastern ridge – and hopefully, if I had time, past it to the head of the canyon with the spring. It’s an area that shows on the map as a jumbled plateau punctuated by a maze of boulders and outcrops, leading farther south to Mesquite Canyon, which I explored a few years ago.

The approach crosses the bajada of the basin and the combined wash that drains the plateau and the spring in the northeast corner. After a little over a mile of bajada, you join the wash that drains the high southern end of the bajada, and eventually hit the old road into the southern gulch, which climbs through a low pass and drops into the big wash that drains the southeastern ridge.

My first objective was the old mesquite tree and its spring. It’s tucked away back in a canyon that winds tortuously between cliffs and fanciful outcrops of ancient granite. I knew there was tamarisk in this canyon, but I was under no delusion of finding water in the spring, which usually has to be dug out of deep sand. And I wasn’t prepared for the state of the venerable tree.

At least it wasn’t completely dead. New growth had emerged from its lower trunk, and I figured it would take a lot more than the current drought to kill a tree with such deep roots. But it was still pretty sobering. The water sources in this range all seemed to be dry – where was the wildlife getting its water?

I realized it had been gradually getting warmer, day to day, throughout my stay. My shirt was unbuttoned all the way down and I had to add sunscreen to my chest.

I climbed up the ledges behind the dry spring and continued up the narrower canyon winding south across the basin below Blockhead, until I reached a bend where I thought I should leave the wash and traverse the slope above. This was a new approach for me – I’d come over from farther west in the past. And on the traverse, I began to be pursued bees. They never actually stung me, but I vowed to take the opposite side on the way back.

Cresting the ridge below Blockhead is another of those magic moments, because you’re suddenly above the Lost World. But since the days were so short now, and I always wanted to get back to camp to shower before the sun set behind the peak and plunged everything into shadow, I realized I didn’t have time to continue to the head of the next canyon. All I could do was gaze longingly at the route above me.

I did have time to climb past Blockhead and check out the continuation of the ridge westward, where again I found natural campsites, level protected places along the crest. And I got even more spectacular views.

I was bee-free on the descent down the opposite side of the drainage, and the hike back across the basin was beautiful in the low light of late afternoon. But I still didn’t make it to camp before shade descended, and had yet another chilly shower.

This was the first night when mosquitos joined me for dinner. The moon was up later, approaching half. And I began to notice more satellites, which really annoyed me. Yes – I’m using them for my GPS messenger, and the images you see on these route maps. But I’m not embracing them happily. They’re a scourge on our night skies.

I thought about the tamarisk I’d seen so far, in three widely separated drainages. Our gulch actually seems to be the worst place in the range – at least here on the west side. The plateau is also bad, but not so much. Here in the desert, after more than a century, tamarisk remains confined to short stretches of drainage, as opposed to along perennial streams elsewhere in the Southwest. And in the drainages where people haven’t tried to “eradicate” it, it seems to have established an equilibrium with native plants, which often thrive in proximity.

Because it’s a wild plant, it’s smarter than you – if you fight it, it comes back stronger. In a place like this, the lesson may be: Don’t fight it!

Since the moon was still up after dinner, I took one of my moonlight walks up the gulch. Moonlight walks have been such a big part of my desert experience! Coming back, I heard a piercing ringing from the north bank, then an answering sound from the south. Crickets? It was really loud.

I thought about the old mesquite, and my favorite willow up on the plateau. Trees here overgrow in wet periods, then die back almost to the ground in a long drought, finally resprouting from their lower trunks. That seems to be a pattern of the desert.

I’m naturally tense, but dinner, beer, and a walk finally relaxed me. Back at camp I continued to study the sky. I saw a red star above Orion and wondered if it could be Mars. Through the binoculars, the Pleiades were so beautiful, and a dense area of the Milky Way below Cassiopeia. In bed, bracing my elbows, I could finally see three moons of Jupiter. Two more meteorites before I fell asleep, and of course the damn satellites.

Next: Day 6

Desert Trip 2022: Day 4

As at home, Saturday was to be my day of rest.

The wind was only a memory. And as I finished breakfast, sitting with my back to the sun, facing the dramatic peak north of camp and watching the occasional bird swoop from boulder to boulder, I was suddenly struck by the silence. At home alone, I’m always listening to music – usually streaming radio from some distant city. It keeps me company. But now, after that relentless wind on the plateau, the silence was welcome.

As occasionally happens, after taking a pain pill the night before, my back pain had vanished by morning. I’d started doing all the right things – stretching, walking a lot, lifting mindfully and using lumbar support – and it troubled me no more on this trip, which after a week under the threat of paralysis was a huge relief.

In the shade of the big boulder at the north end of camp, there’s a little alcove that at this time of year provides shade for one person, so I sat there reading for a couple of hours. I was so still and quiet that a covey of Gambel’s quail came within a couple yards of me, foraging for about a half hour, without ever noticing I was there.

Again, I scanned this landscape of precious memories – the ridges, slopes, canyons, bajada, washes. When I got up to pass from shade to sunlight, I felt the extremes of temperature – it felt like going instantly from the 60s to the 80s – something we’re not used to when living indoors – the power of the sun!

Despite the cool weather, I was frequently pestered by flies, in all sizes. I decided to revisit my old stash above camp – miscellaneous materials for the over-ambitious projects we had three decades ago: a 100 gallon galvanized water tank, some PVC pipe for a well lining, a wheelbarrow, a roll of barbed wire. It was eerie, like stumbling upon the work of a stranger – is that the bail I built, to clean rocks out of the well? Those projects will never materialize now – those materials will likely never be needed by those who come after.

This whole place goes on without me. Despite my early ambitions, I haven’t really made a difference. I’m so little a part of it, virtually insignificant, and that’s probably a good thing.

Back at camp, I discovered sunburn from the past two days of hiking. I’d forgotten to apply sunscreen – a hat protects me at home, but here, the pale, reflective rock, gravel, and sand that cover most of the ground bounce the sunlight up from below.

After lunch I moved to a sitting spot on the now-shaded east side of the boulder. In the past, in really hot weather, I’d always hiked up to the shade house in the side canyon with all the mining ruins. But now, this boulder shaded me enough that I didn’t need to leave camp.

By mid-afternoon the whole camp was in shade of the peak above, and the temperature quickly dropped. I hadn’t been planning to shower, but I had to gather more firewood, and that got me all sweaty again.

It felt like that windy, cold Thursday night on the Plateau had been my test, my trial, and this calm day had been my reward.

The meat I’d bought in Flagstaff last Tuesday had been sitting in my cooler for four days and nights, so I planned to grill it all tonight and keep the surplus for the following nights. I still wasn’t sure how long I could or would stay.

It took a while for the meat to cook – previous campers (maybe even myself) had set the rocks in the fireplace a little too high, and I had to remove some to get my new grill closer to the coals.

As the moon, Jupiter, the stars and Milky Way came out, I was reminded of my lifelong history with the night sky. The reflector telescope I had as a small child, the refractor I got a few years later. That led me to all the science stuff I had growing up, mostly from my dad: the telescopes, a microscope and collection of mounted slides, the Visible Man and Woman models, rocket models.

Life has led me away from science, and all that’s left is the images, the memories they evoke, seeing these things like the night sky as my life draws toward its close, like old friends.

My Dad wanted to do what I’m doing now – he was on that path. One of the inevitable tragedies of my selfish life is that I can’t pass on that desire, that momentum to the next generation.

Part of me wants to believe that only the time I spend here in the desert is real – but that’s not completely true – it’s only a fantasy I’ve believed in deeply.

Moving around camp, I began using my new headlamp out here for the first time – an innovation I finally picked up from other desert friends. At home, it allows me to hike longer, because I can return in the dark. Here, I was figuring out how and when to use it, versus my trusty oil lantern. The problem was I kept forgetting I had the headlamp on!

When the firewood ran out, I went to bed, the screen keeping me safe from buzzing mosquitos, and I saw another falling star before dropping off to sleep.

Desert Trip 2022: Day 3

After that long struggle to get warm in the driving wind and plummeting temperatures, when I did fall asleep, I slept like a log. I woke at 6 am, feeling totally refreshed, as the southeastern sky was beginning to glow above the ramparts of rock surrounding my camp.

But the wind was still roaring unabated through the pinyon, juniper, and tall granite boulders, and even without wind chill, I realized the temperature had to be somewhere in the 30s now. There was no way I was going to crawl out of my tarp cocoon until sunlight reached my campsite.

That was another little detail I’d forgotten in my absence from this place. We feel protected camping next to a rock outcrop or under a high peak, but here, I was essentially down in a hole – at the western foot of a high ridge, where, still without the ability to build a fire in this wind, I ended up lying in shade for another three hours, until the sun finally topped the ridge and began to warm me.

While lying in wait, I remembered seeing a falling star before falling asleep last night – the second I’d seen so far out here. And I began pondering my plan for the day.

During my last visit to this area, a friend and I had hiked to a canyon just south of here, just over the crest that loomed above me now. Our goal had been to relocate a prehistoric olla – a ceramic storage jar – that he and other friends discovered under a juniper near the head of that canyon.

Our hike had been cut short by rain, so I still didn’t know exactly where that jar was, but it tantalized me as another part of the puzzle of our ancient cultural resources. Assuming I could make it safely down the dry waterfall, my hike back to base camp should only take a couple of hours, so if I could find a way from here over to the head of that southern canyon, and if I could make my limited water last, I should have plenty of time for a side trip before heading home.

After breakfasting on granola and an orange – no coffee today – I had less than two liters of water to get me back to base. Which depending on the side trip, could take all day. With the wind, it was still chilly, so I might be okay.

I believed the head of the side canyon was due south of me. I couldn’t see the actual crest, or a saddle which might be my point of access, because of intervening spurs of the mountain, but I could see a drainage that might be my way up. Much of it was boulder-choked, but I could also see some patches of bare, shrub-dotted ground that might provide an easier route. It would be an experiment.

As usual, the terrain proved much more complicated above than it looked from below. But after an hour of scouting routes, climbing over ledges, detouring around giant boulders, and crossing gullies, I found myself exactly where I’d hoped to be – on a ridge that formed the saddle directly at the head of the southern canyon. And there were junipers dotted all around, any of which could hide that olla.

What a place, and what a perspective! The wind was fading to a pleasant breeze, a majestic pyramidal peak rose a couple hundred feet above the head of the canyon, and I had views into the Lost World – the huge southeastern basin – as well as over Blockhead, the granite monolith on the south wall of our own interior basin, which we stare at from camp.

I ended up exploring the entire crest at the head of the canyon, peering under every juniper, but never saw the olla. I did find several great campsites – ridgetops in this range often feature level areas protected by boulders or low rock walls – and a few stone tool flakes. But my water was too limited to explore downward into the canyon.

So I found my way back down to the plateau campsite and packed up for the return to base. I had only about two-thirds of a liter of water left and would eventually start to dehydrate, but it shouldn’t be too bad.

I still wasn’t looking forward to the climb down to the bajada. But when I reached the rim, it didn’t look so scary this time. I took it very slow and careful, but still had a few near-falls – as usual, lucky to recover balance before getting in trouble. And before I knew it, I was back in the big wash.

On the way home, I tried to compare hiking here with the hikes I do back home in less arid country. It’s much more dangerous here. It’s not as hard on the feet, but with the slopes of loose rock and gravel, it can be hard on the ankles. And of course there are the long slogs through deep sand.

I’d finished my water halfway there and was just beginning to get a little dehydration headache when I finally dropped from the bajada into the wash below camp.

Back at base camp, I found a big tarantula nonchalantly strolling past my vehicle – it looked identical to the one I’d passed two days earlier farther up the gulch. My back was still hurting, as was my heel – probably a delayed reaction from the back down the sciatic nerve – so I took a pain pill. I was filthy and overdue for a shower, so I made further attempts to stop the leaking seam – I had a binder clip I use for bags of chips, and rolled up the taped seam, finishing with the clip, which slowed the leak to a slow drip.

All clean, the next chore was dinner. I’d used most of my catclaw the night before the backpack, grilling a whole chicken leg. That produced leftovers, which I would combine and reheat on the stove, but I still needed a campfire. I scrambled to the boulder above camp where friends had a stash of firewood, but the pieces were just too big for a one-person fire. I was taught the leave-no-trace school of fire-building – never use anything bigger around than your thumb. My catclaw fires use branches a little thicker than that, but I’m most happy with small-diameter firewood, and catclaw makes wonderful coals for grilling.

After sundown, as I was working, I was swarmed by clouds of insects that looked superficially like mosquitos, but didn’t buzz – and they bounced up and down like mayflies. The wind had vanished and the air was perfectly still.

I was pleased with my new gear. The folding chair had looked drab, even ugly, at home, but here the colors fit in perfectly, which had been my plan. People buy high-tech gear that looks great in the city, but it can make a campsite look like an REI showroom.

I was surprised and a little concerned about my water situation. I was running through 5 gallons – a third of my supply – in less than two days at camp. Yes, I’d lost a little in the shower leak, but I couldn’t account for the rest. In the old days, Katie and I had never brought more than 5 gallons for the two of us, for a 3 or 4 day stay. But then we hadn’t been hiking like I do now.

After dinner I mused about my fears and lack of confidence on the backpack. It was clearly all in my head, and my habit of pushing myself won out in the end.

Our campsite is elevated on a ledge above the wash, with a 180 degree view across the gulch and interior basin, ringed at the horizon by jagged ridges. Under the star-strewn sky, scanning that dark jagged profile, I was again reminded of how this landscape, which looks so bleak and monotonous to the novice, is for us filled with hidden magic – countless special places we’ve explored and shared, hidden to view until you’re upon them. Just gazing across this landscape triggers memories that span decades, flooding my head and heart. I thought about the desert journals lost in my house fire – all those details that might never return to mind.

In bed, I was soon joined by mosquitos, and got up to assemble the sleep screen I’d found on eBay to replace my burned original. Thankfully, it still allowed me to see the stars clearly: the early constellations of Cygnus, Cassiopeia, and Pegasus, and when I woke hours later to pee, Auriga and Orion. I saw three meteorites, including one that left a long trail.

November 5, 2022

Desert Trip 2022: Day 2

In this transitional season, I’d brought both my warm-weather sleeping bag and my super-insulated down bag, but with the (slightly incorrect) weather forecast in mind, planned to use only the warm-weather bag – a very cheap synthetic bag which is probably only good to the mid-40s.

On that first night I started out with only t-shirt and skivvies inside the bag, but had to pull on thermal bottoms sometime before dawn. Still, it was a deep, full night’s sleep.

But wind had come up before dawn, and when the sun reached my bed and I finally crawled out, it was blowing hard. First order of business was to boil water for coffee, but in the gale-force wind across camp I had to box my stove in to retain the heat, and it still took over a half hour to get it to boil.

The wind was so strong I had to lean into it to cross the campsite, and my back pain returned so that I was forced to walk bent over at the waist, anyway. Then I discovered the wind had blown the solar shower off the hood of the vehicle, and after only one shower, it had burst a seam landing on the rocky ground. I’d lost over a half gallon of precious water. I tried duct-taping it, but it still leaked. I filled it anyway and laid it in the sun upside down so it wouldn’t leak while I was out hiking.

I mentioned the other day that I had no agenda for this trip, but that wasn’t strictly true. I’d brought all the artifacts I’ve collected in past decades, up on the plateau at the “puberty site” below the statue, with the intent of repatriating them. Today I planned to hike up there, return the potsherds and tool flakes, and spend the night – my first backpack in 7 years.

For the past few years, I’d been hiking with about 25 pounds in my Swiss Army surplus rucksack, but for backpacking I would carry at least 10 pounds more, and when I pulled it over my shoulders, that extra weight felt like it would destroy me. I realize that serious mountaineers carry up to 65 pounds, which is simply inconceivable.

The day’s plan seemed crazy from the get-go, and it was only my typical bullheadedness that got me started. My back felt like it was being sliced in half at the waist, and I knew that one wrong move carrying that heavy pack would paralyze me. The pack felt so heavy that I didn’t think I could make it to the base of the plateau, let alone climb that perilous 500′ slope beside the dry waterfall. And the wind – one of our typical desert winds that blows steadily in one direction at 30-50 knots, in this case out of the northeast, and can last for up to 3 days. Assuming it didn’t blow me off the mountain or into a cactus or yucca, how could I possibly sleep up there, where it would be even worse?

Feeling about 100 years old, trudging up the dry, loose sand of the big wash, I forgot to stretch – something I’ve learned to do near the start of any serious hike, to reduce pain and protect my joints. Hiking near home, I’d forgotten how most desert hikes involve long, arduous walks in sand. On the plus side, the long, winding wash that drains the plateau is beautiful, with spectacular rock formations in the bends. And the bright yellow rabbitbrush added some color to this otherwise fairly drab season.

Now for the part I’d been dreading: the 500′ vertical climb to the plateau.

I’ve done this climb at least a dozen times since the early 90s – both solo and with friends, including a couple who haven’t been in very good shape. The last time I’d been up there was in April 2016, by myself. I’ve always considered it a dangerous climb – very steep, requiring many short bouldering moves and traverses of loose rock at the angle of repose, including sizable boulders that appear stable but tip or slide when you put weight on them. And plenty of yucca blades or cactus spines to impale yourself on if you make a single mistake.

But today, despite all that past experience, it truly terrified me. I felt there was a serious chance I’d be injured or even die trying to reach that plateau. I knew I had to try, but I was scared to death.

With a little reflection, I realized the several traumas and close calls in the past few years had undermined my confidence. On the surface, I was in really good shape, doing hikes up to 20 miles in a day, at 2 or 3 times the altitude and with far more elevation gain than I would face here. But those hikes were mostly on trails. I was out of practice for hiking in the desert.

If I did make it, how would I get back down alive? That scared me even more – downclimbing is always more dangerous.

I’d long forgotten the best route, so I just went slowly and stopped frequently. At that rate, after almost an hour, I finally made it up past the giant thumb rock, safely, to the little saddle where you drop over into the dry waterfall itself, and that accomplishment restored some of my confidence.

The next, and most spectacular, stretch involves using some simple bouldering moves to get past the smooth and sometimes slick exposed granite faces of the dry waterfall. I love this part because it’s all rock.

The plateau, which I’ve always considered the heart of the entire mountain range, is a rugged, rolling basin partly enclosed by steep boulder slopes at its eastern head and southern rim, and traversed by a winding streambed that drains from east to west. This area hosts most of the pinyon pine in the range, from the rim down to the wash itself.

It’s obviously favored ram habitat. Shortly beyond the rim I came upon the third ram skeleton I’ve found up here, and after that, some more recent lion scat.

This is one of the wettest parts of the mountains – there’s a sheep drinker with two large water tanks at the head of the plateau, and I’ve found water in the stream more often than not. But underscoring what a dry year this has been, the only evidence I found of water was a patch of damp sand below a discontinuity in the rock, midway up the streambed.

Near the head of the canyon there’s a raised bench or ledge a hundred feet above the south bank of the streambed, marked by a dramatic boulder pile. On that ledge is the most important prehistoric site I’ve found on the west side of the mountains – a truly magical place, the western counterpart of the sacred site on the east side. My sometime friend, the Mojave Preserve archaeologist, said it was most certainly used in girls’ puberty ceremonies. It consists of a large overhanging boulder, with a smaller boulder forming a sort of table under the overhang, and “cupules”, little bowls, ground into the stone tabletop, which he said were used to mix face paint.

The ground for a large area around shows evidence of ancient campfires and is littered with potsherds and the occasional stone tool flake. But in general, it’s a modest site, and raises a whole string of questions. There were no villages or permanent camps in these mountains – the nearest would’ve been on the river, almost 50 miles east, requiring very long treks between water sources. And the historical tribes familiar for these ceremonies were based almost twice as far away, to the west. It’s hard to imagine a small group of teenage girls, accompanied only by one or more older women, carrying pottery jars and other gear many days across the desert and up that dangerous climb, to perform a ritual in this extremely remote, often dry place.

The steady, gale-force wind was still scouring my campsite on the ledge. No chance of a fire tonight – I even scouted between the many big boulders for a calmer location, but the wind was penetrating everywhere.

But with that heavy pack off my shoulders, my energy returned. I did a short hike up the slope toward the statue – I’d been that way a few times, but couldn’t remember my previous route. Not that it matters much – every route involves climbing over, under, or around huge boulders all the way up.

I made it about halfway and realized I didn’t have enough time to go farther. But everything up there – the elegant pines, the house-sized, white granite boulders, the view across the open desert – is beautiful. And in the brief dusk after sunset, I climbed back down to the streambed and made it most of the way up to the sheep drinker at its head, maintained by the Bighorn Society.

With no fire, I had a cold dinner – the same nuts and jerky I’d had for lunch. I’d only brought four liters of water for the overnight, and in this cooler weather, with the wind, had saved two of those for the next day’s return hike.

One problem with backpacking solo is that there’s nothing to do after sunset, especially if you can’t build a fire. There you are, between 6 and 7 pm, with nothing to do but go to bed early! I had a lot of time for reflection, and decided it was time to relax my standards and adopt some modern, lightweight gear – replacing my heavy old canvas and leather pack with something ergonomic, and my cheap sleeping bag with something more efficient.

So I went to bed at about 7 pm, with my feet to the wind so it couldn’t blow sand into my bag. As before, I stripped down before getting in, and was warm at first. But with the wind roaring like a freight train, that didn’t last.

About an hour later, I added my thermal top – essentially a sweater. And an hour after that, with the wind still raging, my legs got too cold and I pulled on my thermal bottoms.

Still another hour later, my legs got cold again. That wind just sucks away whatever heat your body can generate – I’ve even gotten cold inside my down bag, which is good to well below zero. So I crawled out into the frigid night and pulled on my heavy canvas hiking pants, and got back into the bag.

That still wasn’t enough. After another hour, I donned my thermal cap, and an hour later than that, still awake, I got up again to struggle into my storm shell jacket, pulling the hood completely over my head before getting back in the bag. I can’t remember wearing a jacket to bed before, but may well have sometime in the dim past!

Soon it was midnight, I’d been lying awake for five hours, the wind was still raging, and my feet were cold. The only piece of clothing I had left was a spare pair of wool socks, which I managed to fish out of my pack and pull on over my heavy hiking socks, without leaving my bag.

But only a half hour later, I was cold again, with another six hours of increasingly colder night ahead of me. How could I survive? I’d been in this position before, and once, far too cold to lie still, had spent an entire night pacing back and forth, wrapped in a heavy coat, to keep my heat up.

So I tried the only remaining trick – I got up once again in the dark, and folded my plastic tarp over the sleeping bag, so that the open side was downwind. I had no way of holding it closed, but I had a couple of bungee cords that I used to anchor the side and corner of the tarp to my pack.

Amazingly, this finally worked, and I fell asleep almost immediately after.

Next: Day 3

November 4, 2022

Desert Trip 2022: Day 1

On Wednesday morning, only needing to buy gas – filling my cans at Arizona prices then topping up at California prices in the desert oasis – I finally headed west across the desert. The highway has been closed to through traffic for most of the past decade, due to bridges washed out in past flash floods, never to be repaired. We can drive around these washouts, but it’s been great to discourage visits from strangers.

The sand-and-gravel road past the ghost town was graded for a gas pipeline test several years ago, and remains fast to the test site, midway up the fan to the pass. But beyond there, a zillion minor ruts forced me below 20 mph average, and past the airstrip, my speed dropped to between 5 and 15 mph as usual.

I was shocked to see how dry everything is – perhaps drier than I’ve ever seen before. The creosote bushes on the alluvial fan have dropped almost all their leaves, with remaining leaves brown and dead, except for a few shallow drainages where highly localized storms caused a little runoff this year. I think we all hoped this year’s wet monsoon would bring rain to these mountains, but that simply didn’t pan out.

Nevertheless, visitation has really dropped off. The rancher has stopped visiting our gulch, and the only recent tracks on our side road were from a single fat tire dirt bike.

Entering the mountains and dropping into the lower gulch, there was little recent erosion, lots of new growth, and no established vehicle tread, so as occasionally in the past, I had to find my way up the big wash as if I’d never been there before. Our improvised gate was still up – the dirt bike had simply gone around where anti-government vandals had cut our fence – and everything else around camp looked as it had three and a half years ago.

It was great to be home, but I was still under a cloud of stress from back pain, feeling like such an idiot for letting it happen. It would hang over me for the next couple of days, always threatening to paralyze me if I made the wrong move in this challenging terrain.

Stopping for lunch in the pass on the way in, I reached camp around 1 pm and immediately prepared for a hike up the gulch. I had no destination in mind and would decide enroute.

My first stop was at the hidden cache of our shade structure, which remained untouched and sheltered. That cheered me up, along with the health of the riparian vegetation.

Invasive tamarisk had regrown significantly in the mid-gulch, but native vegetation still looked good outside the one historical tamarisk patch. New growth and erosion meant that anything but bike travel up the gulch would now be quite destructive, so it was great to see no one had been here to try.

The day was almost perfectly calm in the wash, and when I reached the outlet of the old road up to the mine, which I hadn’t visited in decades, I decided to head up there. The lower part of the road remains in good repair, and as I climbed, I encountered some nice gusts that kept me from overheating. But the road gains 500′ in elevation, becomes quite steep, and crosses a drainage where it’s been eroded beyond driveability, sometime since the early 90s.

Exploring beyond the ledge where the stamp mill was located and the mules corralled, I discovered a well-built mule trail into a side canyon that I couldn’t remember. I followed it a few hundred feet higher in elevation until it was blocked by a giant cholla next to a cliff a dozen feet high. I vowed to return when I had more time, because this trail seemed like a practical route to the crest, not much farther above.

From there, I climbed over a low shoulder and dropped down to the “swimming pool”, a huge concrete water tank I’ve always fantasized about filling with drainage from inside the mine. And at that point, what had so far been an exhilarating hike turned somber.

A mature bighorn ram had fallen in the tank, which is 12-15′ deep, with no way up the nearly sheer walls. This tank is obviously a trap for wildlife, but the only way I could imagine an adult bighorn falling in, is if it was in flight, perhaps from a lion, bounding up the slope from below, and for some reason unfamiliar with this spot and its hazard.

The fall would surely have broken bones, and with luck, caused a concussion that might’ve made the death by dehydration/starvation a little easier.

It was hard to get that tragic image out of my mind on the way back to camp. Despite the breeze up above, the climb had made me sweaty and I was anxious for a shower – I’d filled my new solar shower before leaving camp. But now I remembered that the sun drops below the peak behind camp early, especially this time of year, resulting in an immediate temperature drop. It was getting windier, and I’d be shivering despite the warmth of the water.

Having failed to bring firewood or charcoal, I gathered dead catclaw on my way back to camp, and after arriving, showered quickly, then started preparations for dinner. That’s when I discovered I’d also forgotten newspaper, which I usually carry in my vehicle for tinder. Not a huge problem – this year’s dried-out annual vegetation is always available – but in a pinch I used blank pages from my notebook.

Living and sleeping indoors, it’s sadly easy to forget the night sky even exists. We’ve often complained about the encroachment of skylighting from distant cities, illuminating our horizon out here, but that first night was a revelation to me, after three years of no camping.

The moon was nowhere to be seen, but Jupiter was rising in the east, and without the moon, it easily dominated the sky. My familiar constellations were back, and I took my binoculars to bed, taking care not to trigger more back pain as I wriggled into my warm-weather bag. My new sleeping pad was, frankly, even more comfortable than the old one. I would almost say it’s more comfortable than my mattress at home.

Next: Day 2