Max Carmichael's Blog, page 17

August 22, 2022

Missing the Desert

This was the weekend when my region was forecast to get extreme rain and widespread flooding. Most of it was supposed to arrive on Saturday, but that turned out to be something of a letdown.

Still, I was sure there’d been enough rainfall in the mountains to raise the level of creeks in canyon bottoms, and most of my hikes involve creek crossings. So I figured it was time to drive over to Arizona and do the big climb from the desert to the fir forest. It was a really hard climb, but with no creek crossings required.

It was a perfect day for this hike, because it’s generally too hot in summer, but today’s cloud cover would fix that. Sure enough, it was in the 60s when I set out from the trailhead, through an overgrazed maze of boulders, mesquite, and big Emory oaks. But the humidity was almost 100% and the head-high vegetation was dripping from overnight rains. So I in addition to waterproof boots, I put on my waterproof, thornproof hunting pants and left my regular hiking pants in the car.

My destination, the mountain crest, was completely obscured by low clouds. And as I approached back and forth through the lowland maze, I was accompanied by the freight train sound of a raging flood not too far off on my right. I was surprised because it wasn’t raining, and I didn’t think any of the drainages near this trail had big enough watersheds to flood. But the trail led me away from the sound and I thought no more of it.

Then, less than a mile into the hike, the trail began climbing and led around a hill toward a narrow gully – the only gully crossing on this hike – and the freight train sound came back. It was coming from the gully! What the hell was I going to find?

I was shocked to find this littly gully, which had never had water in it before, turned into a churning torrent of muddy water, 8-10 feet wide at its narrowest. Then I began to visualize the landscape above, and I realized that the watershed for this tiny gully led 3 miles down from the crest, which was over 3,000′ above. So it was actually able to collect a decent amount of runoff and ultimately funnel it through here.

The logical thing would’ve been to start worrying about what would happen to this flood if the crest got rain later in my hike, but as usual all I could think about was getting past the obstacle. Fortunately there was a log across the surface of the torrent, which could be reached by stepping out on a slippery rock, with another shorter log as an intermediate foothold. And I found a soggy stick I could use to improve my balance while crossing.

But the intermediate log turned out to be rotten and immediately broke in half under me, briefly submerging one of my boots as I scrambled to leap to the opposite bank. Without that intermediate log, would I be able to get back across on my return at end of day?

It always amazes me how a loud a creek can be. Even the smallest creek can sound like a raging torrent from hundreds of yards away, and that sound can really set your nerves on edge if you know you have to cross it at some point.

This trail is very seldom used by anyone other than me, and the last time I’d been here, in March – long before the growing season – I’d gotten lost because the tread vanishes at many points. I knew it would be overgrown after this year’s long, wet monsoon, and it exceeded my expectations. Beyond the flood crossing, I was wading almost continuously through sopping wet chest-high grasses. The crest was still hidden behind clouds, but at least it wasn’t raining – yet!

Most of the cairns that mark some of the turns in the trail were hidden under the tall grass, so I kept having to stop to search for sticks and rocks that would work as route markers on my descent. And as I’ve noted many times before, these trails are always lined with rocks – loose or embedded – and the overgrowth also hides the rocks in the trail, so you have to either go very slow, feeling your way with each step, or be condemned to stumble or lose your balance often.

At times I was helped by a corridor where the surface of the grass had been trampled, and at first I thought another hiker might’ve come this way recently. But gradually I realized the trampling had been done by game, because it often led away from the actual hiking trail.

With all this stopping and trail marking, it took me forever to reach the saddle which marks the halfway point. Meanwhile the sky had darkened and I could see isolated rainfall behind me in the lower range to the south. I was so discouraged by my slow pace that I considered giving up and turning back, especially with the flood danger. But as usual, I threw caution to the wind and kept going, thinking the descent would go a lot faster.

In the next stretch – the final climb to the crest – the dense grass is replaced by scrub oak, and eventually by scattered pines and firs. Here, the trail often turned into a creek. The higher I got, the more it seemed that water was just flowing down the entire slope.

By the time I reached the saddle on the crest, it had taken me 4-3/4 hours to go 4-3/4 miles. My legs were sore and I was tired and out of breath, so I figured I’d just take it easy from here on, enough to enjoy the alpine forest, and turn back well before reaching the end.

But again, my compulsive nature won out. At the high point, there wasn’t even a view to reward me, since the peaks of the range were still hidden under clouds, so I continued down to the highway saddle – the terminus of the trail, which most hikers use as a starting point. It was empty – not surprising in this weather. I’d used up so much time already that I realized I’d get back to the vehicle near sunset, facing a 2-hour drive back home in the dark. So I decided to drive to Safford and stay there in a motel – I thought I might have enough points for a free night. The idea picked up my spirits – Safford is a strange place and could add to the day’s adventure.

Clouds were entering and darkening the forest as I proceeded back down the crest toward the saddle, and before long I ran into rain. The descent did go quickly, but the rain also increased. Realizing I could begin worrying about crossing the flood – at that gully which was still almost 5 miles away, and which was being steadily renewed by this rainfall – I forced myself to smile, on the principle that mind follows body.

If I couldn’t cross that flood, there’s no telling how long I’d have to wait for it to subside. There was no other way off the mountain, and it was too wet to start a fire to keep warm throughout the night. I might be forced to call for a catastrophically expensive rescue – using my GPS device since there was no cell signal. These were the things I was trying to keep from thinking.

As usual, the rain only lasted a half hour, but now, runoff was pouring down the entire slope, and the entire trail was functioning as a creek. As mentioned earlier, the sound of a flood is exaggerated and carries a long distance, so I was accompanied by that freight train roar most of the way down.

I’d never encountered runoff like this back home – I wondered if the geology of these mountains was the cause? Our local mountains, being all volcanic, might be porous enough to absorb most runoff.

In the end, I successfully failed to think about the flood until I literally reached the bank of the gully. It had gotten higher, wider, and angrier, but I could still see the diagonal log, and the sloping rock on the opposite side. I wasted some time scouting unsuccessfully for another stick to supplement the one I’d used in the morning, then gave up and just rushed across as best I could. It turned out to be both precarious and easy.

Evenings are usually spectacular in this valley, and this was no exception. But as beautiful as it was, I was getting really tired of humidity, lush vegetation, and spending nine hours in clothes drenched with sweat. This is really not my favorite kind of habitat to hike in. I was really missing the desert.

Ironically, the motel I got a free night in calls itself the Desert Inn. I knew from experience there were no decent restaurants open on Sunday night, but on the way I remembered I could pick something up at the Safeway and warm it up in the room’s microwave. So I enjoyed a celebratory dinner, a good night’s sleep, and an easy drive home the next day.

While sampling the motel’s breakfast the next morning, I idly studied the local newspaper, discovering that the Forest Service had scheduled a volunteer work session on that very trail for both Saturday and Sunday. Since I’d seen no sign of work or workers, they’d apparently had to cancel due to weather.

August 15, 2022

Life Renewing on the Burned Crest

Much of the story about this Sunday’s hike is not shown in the pictures. Of all the hikes I do in our region, this is the hardest to get to. It’s only 50 miles from home as the crow flies, but like many hikes in our local wilderness, it requires a much longer drive than the hikes I do 80-90 miles away in Arizona.

I always forget how bad the road is. It begins at 5,000′ as a paved 2-lane in good condition. It climbs onto a flat mesa at 5,600′, at the end of which it begins the serious climb, turning into a one-lane with blind hairpin curves and sheer drop-offs with no guard rails. Here, the rough pavement is littered with rocks that have fallen off the cliffs above.

After climbing to over 7,000′ in the foothills, the paved road drops into a narrow canyon where the ghost town nestles. There, the pavement ends, and it turns into a forest road up a dark, narrow canyon lined with flash-flood debris and shaded by old-growth conifers. As it slowly ascends the canyon, fording the creek again and again, it just gets rougher and rockier, until it crosses the creek one last time and begins the serious climb to the crest. Here, I switch into 4wd, and high ground clearance is essential.

Crawling over shelves of rock, slowing for steep sections and erosional gullies, watching carefully for approaching vehicles – including big trucks towing trailers – that I may need to stop or back up for, I finally reach the crest, at over 9,000′. Here, after our exceptional monsoon rains, a section of the road is flooded to 9″ deep, a muddy lake almost high enough to reach the door sills of my vehicle.

It’s always a huge relief to reach the ledge with its big parking area and incongruous permanent restroom. Surrounded by a steep drop-off with a forever view, it’s a platform in the sky that emphasizes how you’ve driven 4,000′ above the surrounding countryside.

I parked next to two other vehicles. I wasn’t particularly surprised – this is a legendary road, and on my one previous hike I’d met a couple from Texas.

We’d been getting a lot of rain, with cloudy skies and cool temperatures. At 9,200′ it was in the low 60s and positively clammy.

My goal was to get as far along the crest as possible, but what had drawn me back here now was curiosity. My previous visit, almost two years ago, had been a few weeks after an extreme wind event had toppled thousands of fire-killed snags across the trail. In a masochistic determination not to let that stop me, I’d fought my way over, under, and around a couple thousand fallen logs, and it was such a miserable experience I swore not to return until the trail had been cleared.

Earlier this year, in late winter, I spoke to the Forest Service trails supervisor, and she’d said that clearing that trail was a priority for the coming season. Then in early June, a hiker posted a report on the most popular hiking website, saying they’d encountered a trail crew clearing that trail and planning to reach the first milestone, a popular saddle below the peak of the range, by the middle of the month. But around that time, our monsoon storms started early, and I could find no update on trail condition anywhere.

So I took a big risk making that epic drive, hoping the trail would be clear.

The most recent entry on the trailhead log, from a month ago, was from a hiker who claimed to have climbed the peak. That was encouraging, because surely the trail to the saddle had to have been cleared. Nobody was as crazy as me, to fight their way through fallen logs just to reach a forested peak that didn’t even have a view!

So I started up the trail, soon leaving the small margin of intact forest behind and entering the moonscape burn scar, which has been filled by a thicket of aspen and thorny locust. I knew most of the crest would be like this. Despite being the highest-elevation trail in our region, it’s not a scenic hike – it runs through a devastated landscape, and your view is mostly obstructed by a dense ghost forest of dead tree trunks. But you do get glimpes, between the snags, of the surrounding mountains, to remind you how high up you are.

Just before emerging from the intact forest, I spotted a hiker up ahead, returning down the trail. He had a big gray dog, and it bounded down the trail toward me. I said something friendly and reached out my hand, and the dog started barking violently, jumping around me in a circle, threatening to attack. The owner approached, and I said, “Your dog seems a little suspicious!”

“No, he never bothers anybody.” Like it can’t possibly bother me to have a dog barking and threatening me. I love how dog owners always deny what’s happening before their eyes – despite the evidence, their pet can’t possibly bother anyone. I’m sure it comes from the lazy owner’s sense of guilt at not making the effort to train their pet – not to mention disobeying the leash rule on public trails.

Because the trail runs along the crest of a ridge connecting the highest mountains, it involves little climbing, and I was hoping I could move fast, and if enough of the trail was clear of blowdown, at best I might be able to go as far as 9 miles, and reach a cabin on a connecting trail, far beyond the highest peak.

And in fact, when I reached the point, about a mile in, where the blowdown had begun, I found a broad path had been cut through the logs. Smooth sailing!

About 3 miles in, the trail switches from the northeast to the southwest side of the ridge, an important milestone for me because you finally get glimpses of the interior of the range, where I do most of my hiking. And about 4 miles in, you reach a rocky outcrop where your view is for once actually unobstructed by dead trees.

And shortly beyond this, the cleared trail ended.

My heart sank when I saw those criss-crossed logs blocking the trail ahead. Why hadn’t they finished the job and cleared it all the way to the saddle, as promised? Hiking to this point, and no farther, made no sense.

Maybe the early storms had stopped them. Or maybe the money ran out. In any event, the Forest Service hadn’t updated its public trail information in almost a year – maybe they were ashamed to admit they hadn’t met their goals.

I knew the saddle wasn’t much farther, so I fought my way through the logs for another half mile. Then I encountered a logjam where the tread completely disappeared in a thicket of thorny locust. That was too much even for me, and I gave up and stopped for lunch in a small, sunny clearing where I sat and watched pollinators working the wildflowers.

At one point I glanced over my shoulder to find a chipmunk sitting on a log about 9 feet away, watching me in curiosity.

A big storm was dumping to the northeast as I headed back. Another began building to the southwest, and just as I entered the margin of intact forest before reaching the trailhead, I felt the first drops of rain.

The other two vehicles were still there. They must be backpacking. I couldn’t believe they’d fought their way through that logjam – another trail started here, running down into a side canyon – maybe that’s where they’d gone.

It rained on and off during the drive back, making for spectacular skies. For once, since my planned hike had been cut short, I would get home early enough to make a decent dinner.

August 8, 2022

Hiker in the Storm

This Sunday’s weather was forecast to be partly cloudy and warm. I’d been having such a hard time climbing – my lung capacity didn’t seem to be recovering – I felt I needed to keep pushing, forcing myself to climb higher on each new hike. And getting up in the higher elevations would help with the heat. Maybe I’d even get some rain.

With the wildfire closures, the only nearby hike I hadn’t tackled yet was my old favorite, which climbs to the shoulder of a 9,700′ peak and continues down a ridge to a saddle with dramatic rock outcrops. It would involve between 4,000′ and 5,000′ of accumulated elevation gain, depending on how far I got.

But first I had to get through the jungle in the canyon bottom, which occupied 2-1/2 miles of the hike. It was as overgrown as I’d expected, a riot of flowers, flies, and waist-high growth with heavy dew, completely covering the trail, soaking my canvas pants. As usual, I was drenched with sweat from the beginning, but in the sections where the creek was flowing above ground, I could wet my hat and head net for a little evaporative cooling.

And I’d worn waterproof boots, so my feet stayed dry.

The long climb to the 9,500′ crest was difficult and slow. I’m beginning to suspect the damage to my lungs was permanent, and I may never regain the ability to climb steadily at my normal walking pace.

I stopped at the spring below the peak, to rinse out my hat and head net. I’d been glad to see no recent cattle sign so far, but unfortunately found a big cowpie near the spring less than a day old. The beast was apparently hanging out in the high country – avoiding the Forest Service’s recent attempt at removal.

Far above the spring, just as I turned the corner into the interior and got my first view of a storm building over the wilderness, it began to rain. I first pulled on my poncho, then when I reached the saddle with its little surviving stand of pines and aspens, I changed into my waterproof and thornproof hunting pants.

Last fall’s trail crew had cleared most of the logs across this trail, but from here on, the main challenge was thorny locust, and they’d done nothing about that. I’d chopped about a half mile of locust with my machete a couple of years ago, but it’s fast growing, and if I wanted to continue I’d just have to fight my way through it.

I knew there would be little reward – after the slow climb to the crest, I knew I didn’t have enough time to reach the rocky saddle, and the intervening trail would just be a thorny jungle with no view and no landmarks. But I still wanted to give my lungs a workout, so I fought my way through the thorns for another mile or so, stopping at an arbitrary point on a traverse just below the crest of the ridge. Through an opening in the locust, I spotted something far down the canyon, a hazy spot that might or might not be smoke.

I watched it long enough to see it drift and change. Yes, there was a little fire down there, apparently a lightning strike. But the whole landscape was saturated, and another big storm was building over the mountains – surely this would burn out quickly?

After I began the hike back up the ridge, the vegetation was so dense that I didn’t get another view of the little fire. But it was soon raining again, and I knew I didn’t have to worry.

At the saddle, I trudged up the little rise that gives a view over the peaks of the range. The northern half of the interior was getting hammered by rain, and another storm was forming outside the mountains in the south.

Lightning and thunder were bombarding me from all sides up there, and the first part of the descent is totally exposed, so I wasted no time descending. The rain fell harder, blowing sideways, but I knew it would move on soon.

After the rain moved on, the air was so chilled I regretted leaving my sweater at home. But as it turned out, the hike down the long switchbacks and through the canyon bottom jungle went much faster than the climb up, and hiking kept me warm.

In the canyon bottom, I was really glad of the waterproof pants now that all that waist-high vegetation was soaked from the rain. Unable to see the rocks in the trail, I was constantly slipping and stumbling. And my third rain of the day began during the last stretch before the climb out of the canyon. I’d been accompanied by the sound of thunder continuously since reaching the crest hours ago.

Driving out of the mountains, and looking back at where I’d come from, I could see storms getting bigger both east and west, over Arizona. And back home, I’d no sooner parked in my driveway than it began to pour.

August 3, 2022

Art File

I’ve described before how the rising cost of living in California had driven me relentlessly from larger lodgings, where I originally had room for art and music studios, into smaller and smaller places, finally ending up in a tiny studio apartment with all my creative work and equipment far away in storage. It wasn’t until I moved to this remote small town in New Mexico that I could afford enough space to get all my work and gear together, and it still took me years to pull a lifetime of art and music out of boxes and set up studio space to continue that work after the dismal hiatus of struggling to survive in California.

Part of that process was finding a readily accessible way to store my thousands of works on paper and canvas – by me and others. For a decade and a half most of those paintings and drawings had been packed away in boxes, portfolio cases, and mailing tubes and stashed in various basements or garages. I needed a big flat file.

I was registered on an online community forum maintained by a couple of older men, 60s hippies who were fixtures in the local progressive subculture. At the end of July 2008, I posted my need for a file, and immediately got a response from one of those guys. It turned out his ex-girlfriend had left him a big flat file made by a local cabinetmaker from local pinewood. But it was stored in a shed way out in the mountains, an hour’s drive from town, and he didn’t have a vehicle that could move it.

So I bought it from him and drove him out there in my pickup truck. It took all day – we had to stop first at a rural settlement on the river to pick up a key, then we slowly drove for miles, winding back into the hills on a rough, narrow gravel road, finally reaching the shed. The file was so heavy that we had to remove all the drawers first to lift it into the truck.

But of course, once I got it home, I was faced with how to get this big wooden box into my house by myself.

First, I borrowed a dolly from a neighbor, and improvised a ramp from a sheet of plywood so I could roll the cabinet off the truck. Then I had to take my front door off the hinges and unscrew all the weatherstripping from the jamb in order to just barely scrape the file through the doorway.

Once I’d walked the awkward thing past my vestibule, put it back on the dolly, and rolled it into place, I could carefully reinstall all the drawers into their ball-bearing slides.

The cabinetmaker had put a huge amount of work into this file – precisely cutting, planing, and joining the pine planks for the sides, building the drawers from scratch, cutting perfect rabbet joints at all the corners. But for some reason he had neglected to finish it, leaving it topless, so John had given me a heavy sheet of particle board to put over it. I covered this with a Mexican blanket so it wouldn’t look so shabby in my living room.

After the Fire

After the FireJust as it was hugely liberating and inspiring to get my music, instruments, and recording gear out of storage after all those years, it was a revelation to rediscover my art. And soon I began a new series of work, filling the drawers of the file to the brim.

But my house fire in August 2020 put another stop to my creative work. I had to quickly remove those thousands of art works, re-pack them in boxes and portfolio cases, and move them back into storage.

Contractors moved all my furnishings out of the house in preparation for interior cleaning and repairs – all except for the file, which was too much of a hassle. It wasn’t until almost a year later, when the flooring subcontractor prepared to refinish my oak floors, that we absolutely had to get the flat file out of the house. So I again removed the drawers, took off the house’s front door and weatherstripping, and with a couple of young construction workers muscled the big thing out of the house and into a tight space in the already nearly full casita in back, in between my bed frame, fridge, and gas range.

In the process, one side of the cabinet was chipped. I salvaged the wedge-shaped piece of wood and quickly stashed it somewhere I thought it would be safe and retrievable, for however far away in the future it would take to fix this thing and get it back in the house.

Working Around It

Working Around ItThe flat file and its separate drawers were now taking up space in the casita, along with most of the other furnishings of my house. I had moved back into and was camping out in the main house, but it was now the middle of winter, and I needed at least one room of that casita as a workshop, to start completing the interior of the house and make repairs to items like the flat file.

I cleared out the workshop as much as possible, but the flat file cabinet had to stay there while I put in the wiring – it was too big to fit through the casita’s other doors. So I worked around it, moving it from place to place as needed.

Repairing the Chip

Repairing the ChipFinally, at the end of March, I was ready to start fixing up the flat file. But by now I’d completely forgotten where I put that missing wood chip. I looked everywhere but couldn’t find it – I would simply have to fabricate a new piece and glue it in. But how to match the original knotty pine? Knotty pine is no longer available, especially here.

Fortunately I had an old piece of scrap pine hanging around that had similar grain and color.

Refinishing the File Cabinet

Refinishing the File CabinetThe body of the file was quite worn, not to mention smoke damaged. But getting the old finish off took two days of heavy sanding, and in the process I discovered it had never been sanded to begin with – the surface was extremely rough under the finish the cabinetmaker had applied.

Like many things around here, it was paradoxical – the unfinished, imperfect product of a lot of obsessive labor.

I also found out early that sanding in the workshop raised far too much dust, and applying the finish indoors generated too many fumes. So I rolled the cabinet outside on my new dolly and applied three coats of polyurethane, sanding between each coat, covering it with plastic every night and uncovering it every morning.

Making Feet & Corner Guards

Making Feet & Corner GuardsThe base of the cabinet was the crudest part of it – inconsistent with the rest of the thing, the base was made out of rough, construction-grade two-by-fours. I wasn’t going to have that sliding around on my newly refinished oak floors, so I had to make feet, to which I would attach protective felt. I made these out of scraps of oak from another project, plus I cut corner guards to protect the vulnerable bottom edges of the cabinet, where the chip had come off earlier.

Moving It Back Into the House

Moving It Back Into the HouseLike a fool I was determined to get the cabinet back into the house by myself, and it did not go well – after taking off door and weatherstripping again, there was still only about 1/16″ clearance between the sides of the cabinet and the door jamb, and I ended up scratching up my new finish in a few places. But those were easily repaired.

Installing the Feet & Corner Guards

Installing the Feet & Corner Guards

Reinforcing the Cabinet

Reinforcing the CabinetI spent weeks puzzling over how to make a top for this cabinet. It would have to span over a yard of open space without warping, and there was no room to add bracing within the existing cabinet – the top would have to be framed above the existing front, sides, and back.

Plywood wouldn’t do – it should be solid wood – equivalent, if not superior, in quality to the expertly joined sides. But I didn’t have access to a broad selection of cabinet-grade wood – our local lumber yard only stocks a limited selection of “project boards” in poplar and oak up to 12″ wide. And I didn’t have the tools or setup to match the joinery of the sides.

Meanwhile, I realized that the top would need to be removable! A fixed top would prevent access to the drawer slides inside the cabinet, and they are mechanical parts that can wear out and break and need to be replaced. I decided to make the top hinged at the back with a continuous piano hinge.

A removable top added even more complexity to a project that just seemed to keep growing. And whereas a fixed top would reinforce the whole cabinet, a removable top would place stress on a structure that didn’t seem to have enough bracing as is. The top front crosspiece was so flimsy you could bend it up and down with one hand.

So I cut a couple of oak boards as cross braces for the body of the cabinet – they would just barely fit above the top drawer, and would stabilize the cross member in front, as well as to prevent warping of the sides. They would also need to be removable to facilitate getting your whole body inside the cabinet to work on the slides!

Building a Top for the File

Building a Top for the FileWe didn’t have any cabinet-grade wood panels available locally to cover the entire top, but I finally figured out a way to combine two different woods without more expensive tools. In addition to the oak boards, the lumber yard had a few 24″x48″ cabinet-grade pieces of birch plywood with a nice surface grain, and I was lucky to find two pieces that were book-matched.

I used the oak as edge binding and to join the two pieces of plywood down the center. I still didn’t have long clamps, but I managed to get enough pressure using bungee cords, and a doweling jig, to get reasonably fine joinery.

Being all hardwood, the top ended up really heavy.

Installing the New Top

Installing the New TopOnce I’d decided to hinge the top, I worried for weeks about how to align the hinge. Both the cabinet and the top were really heavy pieces, and the hinge would need to be attached with the top open, in such a manner that the top would be aligned with the cabinet when closed.

And the fit was not perfect – the original cabinetmaker hadn’t cut the sides perfectly straight, and I hadn’t thought to plane them earlier. Ultimately, searching online, I found adhesive-backed felt tape to line the interface between top, sides, and front. This would help keep dust out. I ordered it the week before I left for Indiana, and it was waiting for me 6 weeks later when I got back from the hospital.

To align the hinge properly was extremely complicated and took three tries, drilling a few holes at first, mounting a few screws, setting the whole heavy thing upright, relocating some holes and screws, lowering, removing and reattaching, etc.

And finally, I discovered that my house floor is uneven, and the cabinet flexes as it’s moved around the floor, so that in some positions, the hinged top is out of alignment, whereas in other positions it’s perfectly aligned. So I gave up and accepted imperfection.

I also realized that the cheap piano hinge from our local Ace is not really sturdy enough for the weight of this top. But it took me so long to install it, I’ll leave it as is for now, letting the next owner worry about that.

Refinishing the Drawers

Refinishing the DrawersI kept thinking I was almost done, until I realized the drawers still needed to be sanded and refinished – all 8 of them.

First I had to remove the wooden pulls – they were originally unfinished, and I decided to spray paint them black.

Refinishing the drawers took over a week, partly because I first sealed them with Danish oil to deepen the color, and I had to wait a day and sand between each coat. I had to keep moving them from place to place after each of the 4 coats, to keep them from running and sticking together, and to keep them free of dust from another project I was starting in the shop.

Installing the Drawers

Installing the DrawersFinally the drawers were ready! I assumed the project was done – what a huge relief! The last big piece of furniture repaired and restored to my house, almost two years after the fire!

I carefully carried each drawer from the casita, up onto the back porch, through the kitchen, and into the living room. When they were all there, I started by inserting the bottom drawer into its slides. These drawers have always been a tight fit, needing several firm pushes to get all the way in. But after the second firm push, one of the drawer sides exploded and ball bearings shot out across the floor.

I wasn’t finished after all. And thank god I’d made that top removable!

So I order a new set of slides for the bottom drawer, and waited another week for it to arrive. And meanwhile, I finally found that missing chip from the side of the cabinet. It was in the bottom of one of the drawers. If only I’d found it months ago, I would’ve saved a couple days of work fabricating a new patch, and the cabinet would’ve ended up looking better. So it goes.

But how to prop up the hinged top so I could work inside the cabinet? I hadn’t included that in my design yet, and there wasn’t much room to work with inside the cabinet. After a few days of design experimentation, I came up with the solution you see below, which works great.

August 1, 2022

Long Walk For a Shallow Dip

We’d been getting regular cloud cover and occasional rain in town, so I expected fairly good summer hiking weather. Like last weekend, I hoped I might even get some cooling rain in the mountains.

On the drive north, the sky was clear to the west, but there were broad, high clouds over the mountains on my right. And I was excited to get a little rain on the windshield as I headed toward them, but it didn’t last.

I knew just what hike I wanted to do, but I was a little worried when I crossed the river on the highway – it was in flood, 4 times its normal flow. To get to the trailhead, I had to drive across one of its perennial tributaries. Would that be in flood too?

But when I got there, emerging from a shady sycamore grove, the creek’s flow was normal.

This is one of the only two major perennial streams in our mountains that isn’t called a river. The trail begins near the creek downstream, and climbs over several ridges to meet the creek again deep in the wilderness. I’d only been there once before, briefly. It was a hike of over 15 miles round trip, the most I’d done since my illness. If I could make it all the way, I would deserve a dip in the creek!

On the long approach up a rolling basin, I was distracted again and again by wildflowers. The morning temperature was in the 60s, but the humidity is so high now, I was soon drenched with sweat again.

Finally I reached the steep climb to the pass, and now I was really sweating! On past visits I’d found these seemingly endless, exposed switchbacks the most daunting part of the hike, but now I didn’t mind them so much. At least I was getting an occasional breeze.

Beyond the pass you enter the backcountry, a land of deep canyons, burn scars, multicolored layers of rock and dramatic formations, with the crest of the range on your horizon. I’d always thought of this next section of trail as a seemingly endless traverse without much elevation gain, but this time I experienced it completely differently – as an endless series of steep erosional gullies lined with loose rocks. Just goes to show how much our experiences depend on psychology.

The reward at the end is the ponderosa pine “park” – a small, shady, grassy plateau before the trail becomes a ridge hike. But today, I’d been plagued by flies all along that traverse, and as expected the flies were even worse in the park. So I just rushed through it to the descent to the ridge.

On the ridge you are high above the canyon of the creek, with spectacular views to left and right. In the first saddle below the park was my first decision point – the junction with a trail that could be my short cut to the creek. I stood there a while trying to make up my mind. Although the temperature was probably only in the 70s, I was dripping with sweat and really wanted that creek, but I also wanted this hike to be an improvement on last week, with more mileage and/or elevation, and if I took this shortcut it would end up almost identical to last week’s hike.

So ultimately I decided to keep going up the ridge to the next creek crossing.

About another mile along the ridge, the trail begins descending steeply into the canyon, through burn scar regrowth, across erosional gullies, over more fractured white rock, much of it exposed with spectacular views of high peaks and multicolored cliffs of volcanic rock on the opposite side. I kept pushing the head net up from my face, thinking the flies were gone, only to have them return in swarms, dive bombing my eyes and nose.

When I reached the creek, deep in the wilderness, it looked completely different – narrower, choked with vegetation, its bed rearranged by floods. And the flies were terrible. There was no swimming hole, only a shallow channel choked with rocks, but all I could think about was shedding my damp, stinky clothes and getting in, somehow.

I found a channel between rocks that was deep enough to lie back in, and rinsed out my shirt, hat, and head net. The water wasn’t actually cold, but it felt marvelous after that sweaty hike! And while I was wet from the creek water, the flies briefly left me alone.

It’d taken me a long time to reach that crossing – a walk of close to 8 miles – and I knew the hike back would seem truly endless. But first I had to climb out of the canyon, about 800 vertical feet, and I had to take it slow – my lungs were still struggling, and I wanted to preserve the memory of that dip in the water and not get overheated.

Clouds had been massing over the crest in the distance – it looked like there might even be a storm elsewhere in the range. But not here. I knew the temperature couldn’t be above the low 80s, but it felt like the high 90s with all that humidity.

Finally I left the ridge and climbed to the pine park, where the flies swarmed me with a vengeance. And from there forwards, the trail really felt unfamiliar. The “traverse” back to the pass and the open country beyond the mountains felt even more endless than usual, and the rock-lined erosional gullies were harder to descend than they’d been to ascend. With my compromised foot and hip, I had to take it slowly and carefully.

And despite the approach of evening, it didn’t get any cooler. Over the pass, down the endless switchbacks to the foot of the mountains, and then the two-mile slog out the rolling basin, the sun burning down on me all the way. Dark clouds were moving out from the crest of the range, but that dip in the creek was only a distant memory by now!

July 25, 2022

Hike of Many Chapters

I always assumed this is my favorite hike because of the views – especially the view of the first canyon, lined with spectacular rock formations. And because it takes me to a place that feels remote, wild, liberated from the cramped, petty world of men.

But today, on my return hike, I realized that one reason why it feels so remote, is that the route passes through a dozen distinct habitats, topographically different and memorable places, each of which is like a chapter in the story.

I didn’t photograph all of these places today, since I’ve photographed them all abundantly many times before on previous hikes. Like it or not, this dispatch is more textual than visual.

I’ve also noted, after previous hikes, that this is one of the most difficult hikes I do. Since I’m currently weakened, recovering from illness, I didn’t know how far I would get. The hardest part is the climb out of the second canyon. Before tackling this trail, I mostly stuck to peak hikes, where you do all the work on the morning ascent and are rewarded by an easier afternoon descent. It still surprises me that I’m willing to descend that brutally steep and rocky trail early in the day, knowing I’ll have to climb back up it later, when the day is potentially hotter.

Our monsoon seemed to be returning after a hiatus, but this morning was still clear, sunny, and hot. I wore my waterproof boots and carried the waterproof hunting pants in my pack, hoping to get some rain later, but I was already drenched with sweat within the first mile.

Like other trails on the west side of our wilderness, this one starts by descending into a canyon, traversing down its west wall for about a mile up canyon. These canyons have steeper walls than most – sheer cliffs in some places – and the mostly exposed traverse through pinyon, juniper, and scrub oak forms the first chapter of the hike. As you traverse up canyon and descend toward the creek, more of the view ahead is revealed.

At the bottom you enter the riparian forest, with ponderosa pine forming the canopy and dense scrub willow lining the creek. In this very narrow canyon there’s no floodplain, and after crossing on stepping stones to the east bank, the trail continues upstream through the lush riparian forest for another third of a mile.

The third chapter consists of the thousand-foot climb up the eastern wall of the canyon, on a series of long switchbacks that progressively reveal more and more of the spectacular rock formations farther up the canyon. The slope above and below the switchbacks is often sheer, so the view is vertiginous.

At the top of the switchbacks, the trail cuts east into a shallow hanging valley lined with evocative rock formations. In pinyon-juniper-oak forest again, you work your way up to the head of this hidden valley, where finally you emerge onto a sort sort of saddle with a small rocky peak looming above.

The climb to that peak, on dozens of short switchbacks in loose rock at an average grade of 30%, is one of the hardest parts of the hike. Fortunately, it’s only 400 vertical feet! But when you get up there you have the most expansive views of the entire route: north to the crest of the range, east to the heart of the wilderness, west to the mountains of Arizona. This little peak forms the western edge of the rolling plateau you cross to reach the second canyon.

But even this central plateau is divided into distinct, memorable chapters. First, the long, mostly level walk on a surface of shattered white rock, winding between low scrub oak and manzanita and open patches of short ponderosa, mostly exposed with 360 degree views, feeling like you’re up in the sky although the elevation is only 7,200′.

Then you descend on ledges into a hidden valley, a couple hundred feet deep, where you cross a long patch of soft red soil, enter a dense ponderosa forest, and eventually begin climbing up a chaotic, deeply eroded slope which forms the next, and ugliest chapter of the hike.

That slope takes you to the rim of the second canyon, where you face the impossibly steep wall of Lookout Mountain, a long, nearly level ridge whose western wall consists mostly of 2,000′ tall talus slopes.

From this trail, Lookout Mountain is your theatrical backdrop as you begin to descend more than a thousand feet, in stages, into the second canyon.

The first stage is down the gully of a dry, vegetation-choked hanging drainage that you can’t see out of. This gets tighter and tighter, finally leading to a patch of shady mixed-conifer forest with such a shallow slope that it feels like a plateau.

The trail skirts this ledge and begins the final descent into the second canyon, which you dread, knowing you’ll have to climb up it on the way back. This part of the trail consists of loose rock with an average grade of 30%, zigzagging back and forth through a mixture of scrub oak and ponderosa along which you judge your progress by peeking through gaps in the forest at the wall of Lookout Mountain across the canyon.

Finally, again peering down through gaps in the forest and scrub, you spot more level ground below – the shady pine and fir forest above the elevated floodplain of the second creek. This is a huge relief!

That forest steps its way down to the grassy meadows of the elevated floodplain, where Lookout Mountain looms above at its full 2,000′ height, and you can barely hear the creek flowing below.

The trail continues steeply down to the willow thicket lining the creek. I was so hot and sweaty at this point I was looking forward to stripping down and taking a dip, but the wide creek is too shallow at this point, and when I took off my boots and socks, I realized that I had to keep the biomechanical tape and felt on my left foot and ankle – I’d need them on the return hike, and I wasn’t carrying spares. So all I could do was soak and rinse out my sweat-drenched hat and shirt and hope those would cool me a little.

Plus, monsoon clouds had been gradually building over the wilderness, stirring up cool breezes over the creek. So I spent the better part of an hour creekside, vowing to add spare tape and felt to my pack so I could immerse myself on future hot-weather hikes.

By the time I faced the brutal climb out of the second canyon, clouds had extended over it, giving me welcome shade. But in my compromised physical condition, it was still brutal and seemed to take forever – up the precipitous, rocky, seemingly endless switchbacks, up the claustrophobic, vegetation-choked drainage, and on the final climb in loose dirt at a 40% grade to the saddle at the top, where you face the steep descent on the chaotic eroded slope into the shallow hidden valley. Reaching that saddle felt like a major step forward in my recovery! I might not be able to hike as fast as I could a few months ago, but I could plod my way up the steepest slopes.

From there on, I had alternating sunlight and cloud shadow. Hoping for rain, all I got was occasional breezes and the sound of distant thunder from the east.

After crossing the plateau of white rock and scrub, I reached the little peak with the expansive view west, where I could see storms forming far away. Down another steep slope in loose rock, and out the hanging valley to the start of the switchbacks that descend back into the first canyon. It was a long descent, getting hotter the closer I got to the creek, simply due to reduction in elevation and the hothouse microclimate of the narrow canyon bottom.

The final traverse out of the first canyon seemed especially hot and endless. It wasn’t until an hour later, as I drove up the hill entering town, that I finally encountered rain, and by the time I got home it was a downpour.

July 18, 2022

Hot, Slow Climb Into the Sky

I was half inclined not to hike this Sunday. I hadn’t felt good on Saturday, and Sunday was forecast to be hot, reaching the low 90s in town.

I’d just finished repairing my deer-damaged 4wd Sidekick the day before. It seemed okay, but most of my favorite hikes involve long drives without a cell phone connection, and after an impact like that I wasn’t sure I wanted to immediately put it to the test.

There are typically two ways to get away from the heat: elevation and shade. But all the high-elevation hikes within an hour of town are either closed due to fire or involve long approaches through hot, overgrown low-elevation canyons.

Finally I realized that my best option actually involved the longest drive. One of the coolest places I know is a hanging canyon ranging from 8,500′-9,000′ down on the Arizona border, with a shady old-growth forest at its head. And most of the drive there retains full cell coverage and AAA road service would be available if the Sidekick broke down.

It was counterintuitive because if it was in the low 90s here, it would be 100 degrees at the entrance to that range, which is 1,000′ lower. But the trailhead is actually even higher than here – 6,500′ – and I would get there early enough so the climb to the canyon should be bearable.

The drive was a real leap of faith in my vehicle and my repair job. Not only did it start with 1-1/2 hours of high-speed, high-temperature driving, but it ended with a thousand-foot climb up the incredibly rough, rocky, high-clearance 4wd-only road to the trailhead, which few people besides me are willing to risk anymore. But the Sidekick performed perfectly.

I was drenched with sweat within the first half mile of the gradual climb up the first canyon. Our early monsoon rains had ensured that the trail was more overgrown by vegetation than ever, and I saw no evidence that anyone else had used it in the past month. Except bears! I found a continuous trail of fresh scat all the way up.

When I reached the switchbacks that take you to the high pass into the hanging canyon, I found a real puzzle. I was already fighting my way through thickets of thorny locust when I came upon big branches of elderberry that had been torn down, so that they blocked the trail and had to be climbed around. Dozens of mature branches, a dozen feet long and over 2″ thick, had been violently broken off, far back from the trail, requiring a long reach and a lot of strength. More strength in many cases than a human would have – and there was no sign humans had used this trail during the growing season, and why would a human pull down vegetation to block a trail anyway? It could only be bears, but bears don’t eat elderberries – all the berry clumps on the branches were intact.

Another surprise occurred when I reached out my thumb to touch a herbaceous leaf that reminded me of mint. I recoiled in pain at the lightest touch – it was stinging nettle! I’d never encountered stinging nettle in this region, but suddenly it seemed to be everywhere on this trail.

Wikipedia says stinging nettle is only native to the Old World, which is patently false. My aboriginal survival course in southeast Utah had included a lesson in how to cook and eat the native species. But in the more than 3 decades since then, I’d forgotten about them. On this trail, it was literally impossible to avoid touching them, so I was plagued by stings throughout the day. Why had they all sprung up suddenly this season, in this place, for the first time?

My lungs have turned out to be the slowest part of me to recover from their near-fatal crisis 2 months ago. Drenched with sweat, with little forest cover, I had to stop over, and over, and over again on the way up to the high pass, to catch my breath. When I finally crossed into the hanging canyon, and made the long traverse to the creek, it was loudly rushing, but it was no shadier and no cooler down there. The many crossings of the rocky, log-choked gully have always been a slow passage. As beautiful as it was, a riot of wildflower color, I found myself trudging and yearning to reach the upper end where the trail enters the shady forest.

I couldn’t believe how hard it was for me to hike uphill. The slightest grade just wore me out. Would I ever recover the capacity I had before the illness?

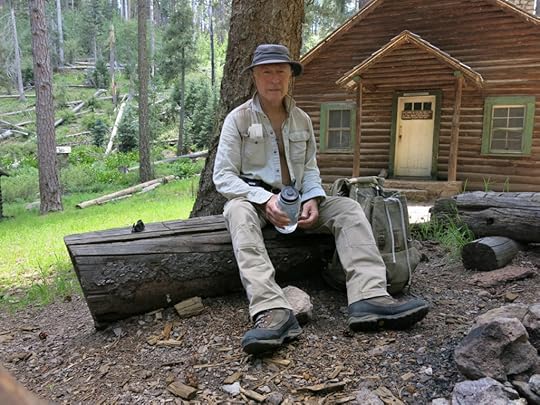

I stopped at the Forest Service cabin, just below the crest, to rest in the shade of the big pines and firs. The trail to the crest is 4 miles, gaining 2,750 vertical feet. It’s always been a difficult, slow trail, but today it was taking me 3-1/2 hours to hike those 4 miles – painfully slow.

Somehow, leaving the cabin, I got a second wind. I couldn’t climb any faster, but I’d trained myself to walk at half my usual pace, which enabled me to go farther without stopping to rest. And the saddle at the crest trail junction, with its long view toward Mexico, was carpeted with yellow flowers. A young couple was coming back up the crest trail – like most people, they’d done the long, slow drive to the alpine campground several miles north, so they could do the easy crest hike, which involves little elevation change.

I’d started this hike not knowing how far I would get. But from the junction, it was an easy hike north through shady forest to the next saddle, so I continued that way.

I typically pick my turnaround point based on my planned end time minus my actual starting time, divided by two. Closer to home, I usually have 9 hours to hike in summer, but over here, 8 hours is usually the most I have, in order to reach the cafe before closing time.

But when I reached the saddle where I’d planned to end my hike, I realized that despite the ascent taking so long, the descent would be much shorter – at my usual, much faster, pace. That might give me extra time to climb the 9,700′ peak above the saddle.

It’s not much of a peak – the original south side forest burned by the 2011 wildfire has been replaced by aspen thickets, so there’s barely a view. But the remaining forest makes for a nice shady spot to lie in the grass, and the minimal view of distant peaks peeking above the young aspens reminds you that you’re high in the sky.

A variety of birds were passing through, there was a nice breeze, and monsoon clouds were forming all around, occasionally drifting over the sun and providing even more cooling shade. My clothes were so drenched with sweat from the hot climb that they wouldn’t dry out until long after the hike, but I’d learned to ignore that minor discomfort, whenever my body had a chance to temporarily cool off.

In the past, I’d always tried to hike as far as possible, so I was left with no margin on the return and had to descend way too fast, which was hard on my joints. But today I felt I had enough time to return slower than usual. Hah! My joints still didn’t like it at all.

The flies had been with me all the way up, but on the return they became much more aggressive – maybe because of the rising heat – so I finally pulled on my head net. And the stinging nettles seemed to be jumping out at me at every turn.

But I got back to the vehicle with plenty of time to reach the cafe, for that beer, that burrito, and that room for the night. Amazingly, despite how hard and slow it had been, I’d hiked over 10 miles and climbed almost 3,300′, which represented a significant improvement from last weekend. Maybe I really was recovering!

July 12, 2022

Three Weeks in a Hospital, Part 3

Thursday May 26 – Sunday May 29:

Surprisingly, just as some of my symptoms disappeared and some of the more intensive treatments ended, I was finally moved out of the cramped shared room in the 4th floor general unit, to a private room in the Progressive Care Unit on the 6th floor. My eye and head were hurting too much for me to figure out why at the time, but a nurse did explain that the PCU was a “step-down” from the ICU, for patients who needed frequent attention but less intensive treatment.

Much later, as I began to comprehend the hospital system, I realized that the move from ICU to the shared room had probably occurred because they didn’t have any other option – they needed the ICU room for a more urgent case and there was nothing available in the PCU. The whole time I was suffering next to that self-destructive kid, dreading the next painful procedure and ignored or brushed off by the harried Med-Surg nurses, my hospitalist was simply waiting for a private room to open up in PCU.

During the past week, I’d been visited on a daily basis by a tall, young female doctor who seemed vaguely of Asian descent, but had a Spanish last name. I’d never figured out her role, and she seemed to have no relationship with the other specialties. But in PCU, I asked my new nurse who she was, and learned that all along, she’d been my hospitalist – the doctor who was supposed to have oversight of my case.

So the next time she arrived, I explained my confusion and concern, and asked for a review of everything that had been done and was being done by all the specialists. She relaxed in a chair at my bedside and asked me to describe what I knew already. And then smiled and said I was correct on all points – there were only a few things she needed to add. I liked her, but unfortunately she didn’t inspire any of the confidence I’d come to have in the senior specialists who’d dominated my care so far.

From the beginning, I’d made a relentless effort to cultivate good relationships with my nurses. After nearly two weeks, there’d been so many of them! Most of the younger ones turned out to be “travel nurses” who were taking advantage of high COVID-era pay rates to sign short-term contracts at hospitals all over the country.

But it hadn’t been easy. From the depths of my brain fog, I sometimes had to summon the rusty skills I’d once used leading professional teams in the tech industry, to keep the nurses from becoming my enemies. The biggest battle I faced was for pain meds. Under pressure from our society’s campaign against opioid addiction, which patients and doctors view as a War on Pain Relief, my nurses started out by claiming that nothing stronger than Tylenol was available. Then when, in my friendliest, calmest and most tactful manner, I revealed that I was aware of and had used stronger meds, they immediately assumed I was a devious addict trying to manipulate them. As nurses, the approval of stronger meds was out of their hands anyway – I would have to convince them to ask the hospitalist, so it was up to someone predisposed against me to convince someone I couldn’t even talk to.

When I asked for pain relief, the nurse would always demand, “But what is your pain level?” As someone suffering from chronic pain from multiple sources for decades, I’ve learned how to use the universal 10-point scale with great precision, often as a tool in recovery and rehab. So far I had felt no discernable improvement from the IV steroid. After a couple days of that, plus Tylenol, the eye pain still ranged between 7 and 8 on the scale of 10. But after a week of my best negotiating and superhuman patience, something suddenly changed. The absent hospitalist abruptly relented and approved the pain relief I needed.

At first we tried 5 mg of oral oxycodone. This helped, but only by a couple of points on the scale, so finally, I was approved for a minimum dose of dilaudid – hydromorphone, one of the strongest pain meds – via IV. That finally did the trick.

Doses could only be administered at 6-hour intervals, but I was now allowed to specify which drug I needed at each dose. New nurses continued to give me a hard time, either treating me like a criminal or claiming the meds were ineffective. But over a period of several days alternating dilaudid and oxycodone as needed, my pain level subsided from 8 to 3. After two weeks of severe eye pain and headaches, I was finally getting some relief! My head cleared, and I could actually start to think again. I could tolerate light, and read my iPad. Finally I had something to occupy me during the hours I lay awake, alone in bed!

My 70th birthday came and went. One of the specialist doctors did notice, and in passing, briefly wished me a happy birthday.

Abandoned in LuxuryMonday May 30

Nurses began dropping hints that I was going to be moved again. I told the hospitalist that I couldn’t deal with a shared room, but when someone suddenly showed up to move me later that day, I ended up in a room with two beds.

I told the orderly that wouldn’t work, and was wheeled back into the hallway, where the “charge nurse” threw a fit, saying no one had told her I needed a private room. So my bed was parked in the hall for another half hour – after which I was wheeled into a huge, luxurious private room with a wall of windows. After 2 weeks, I had returned to the same unit I’d started out in, right after leaving the Emergency Department.

But after being moved I was left alone for what seemed like hours. There was no one to take my vital signs, give me scheduled meds and hook up my IV, perform the next scheduled blood draw. The whole unit seemed almost abandoned – eerily quiet, with little foot traffic in the hallway. I kept calling for help, getting more worried each time, until finally my new nurse arrived and said this unit was for patients who needed less attention.

The rooms as well as the hallways here were decorated in soothing pastel colors, with large-format nature photos framed under glass. My room had a big modern sofa and several large armchairs in like-new condition. And I had a large private bathroom with ornate tiled walls, where I could see for the first time, in the mirror, how much weight I’d lost, how much muscle. My skin was all wrinkled and hanging from my bones.

I continued to get sporadic visits from the infectious diseases and neurology teams. Test results continued to trickle back from distant labs. Everything except the HSV2 and fungus continued to test negative. The effectiveness of the steroid was ambiguous. I believed it was another mistake that had put me at future risk. But they hinted that I might need another lumbar puncture, to rule out autoimmune disorders.

Skin-Walking Nurse

Skin-Walking NurseTuesday May 31 – Friday June 3

My Asian-Hispanic hospitalist announced that she was going on break, and her replacement would take care of me from now on. And the next day, when the replacement showed up, she said she was getting ready to discharge me!

I was shocked, and said so. The specialist teams hadn’t arrived at a diagnosis that would explain all my symptoms. The antibiotic, doxycycline, had run its course, but the antiviral, acyclovir – for the HSV2 in my spinal fluid – was still being administered daily via IV. My eye pain still needed strong main meds which would not be available at home. I was still sweating through my bedding every few hours.

The new hospitalist quickly backtracked. She would reach out to all the specialist teams, get them together for a conference, and determine what more needed to be done.

After the shift change that night, my new nurse arrived – a big man with black hair braided in a ponytail down his back. “You’re from New Mexico!” he exclaimed, reading my chart. “I’m from New Mexico!” He turned out to be a Navajo nurse from south of Albuquerque, on contract here for another couple of months. This encounter was one of the few highlights of my hospitalization. So alone, so isolated, now I felt like I had an ally from back home. He was my night nurse for 4 or 5 nights, and he was an expert at blood draws, which continued to be scheduled throughout the day and night. One night when he woke me up for the 3 am draw, I complained that he’d taken me by surprise. “I creep around in the middle of the night,” he said. “I’m a skin walker!” – a Navajo demon.

As most people are aware, they never let you sleep through the night in a hospital – interruptions are always scheduled, from meds to blood draws. I have sporadic insomnia at home, and was usually able to catch up after most interruptions, but the biggest challenges were to maintain a friendly, accommodating attitude when awakened from a deep sleep at 2 am to have a needle stuck in my arm, and to quickly figure out a breakfast order when awakened by the food service rep after a near-sleepless night.

Now the pain was under control, I was reading books and streaming my favorite radio stations on the iPad, actually discovering new music and adding it to my notebook. And the nurses were digging it. As much as I resent our dependence on devices, I would’ve been lost in that institutional environment without the iPad.

Vague memories of the fiction of Kafka rose up in my recovering mind, and I spent several days researching the author online. It was clear that my experience had been Kafkaesque in the popular sense, but the research gave me deeper appreciation and respect for the complex but short-lived author.

Whereas throughout most of this illness my periodic sweats had started on my forehead and spread throughout my body, they were now focused on the back of my neck and my butt. If I felt one coming on and got cold packs from the nurse soon enough, I could head off most of the uncomfortable sweating.

However, during most of this hospitalization I’d lost much of my control over hygiene and grooming. Nobody ever seemed to understand that I was sweating through my bedding and it needed to be changed at least daily. Nurses had occasionally wiped me down with antiseptic pads and brought me packets with toothpaste, toothbrush, and mouthwash that I tried to use at least twice a day. Midway through that stay in the awful shared room, I requested a razor and got up to shave for the first time in over a week.

But now, with not only a large bathroom but a pile of clean towels and washcloths, I could get really clean and shave as often as I liked.

After a week’s hiatus, the Physical Therapy folks found me again. I’d lost so much weight, so much muscle mass, and was so weak I didn’t know how I would ever regain my strength and capacity. “I climb mountains!” I kept reminding the therapists, afraid nobody in this low-elevation flatland would appreciate how much I had lost and would need to recover.

Our walks were now restricted to the small area of my current floor and unit, but at the halfway point there was a luxurious visitor’s lounge with a large aquarium featuring beautiful, flamboyant tropical fish, where we always stopped for a few minutes. And I really enjoyed getting to know my new therapist, a young woman from Saudi Arabia who was completing her education here before returning home with her family. As we watched the fish milling about behind their glass she confessed she was afraid of animals, especially dogs and cats – a healthy phobia in our pet-crazed social media world.

This Is Spinal Tap

This Is Spinal TapTuesday May 31 – Friday June 3

In response to the new hospitalist, the rheumatologists returned, continuing to question me and review blood results regarding possible sarcoidosis, a mysterious inflammatory disease that can affect multiple organs. But they could never find clear indications.

The neurologists did order another lumbar puncture to test for auto-immune problems and to see if the spinal fluid had changed. Being clear-headed at last, I was even more apprehensive, which got worse as day after day doctors and nurses predicted the puncture would be done that day, only to have it postponed yet again.

When an orderly finally arrived to take me to the basement, my mom had just shown up for a visit, after another of her heroic marathon walks the length of the massive complex. I could only wave and say I’d be right back.

Instead, I was taken to a curtained alcove in a larger room, where I lay abandoned, with no explanation, as technicians huddled across the dark room, their backs to me, gossiping around a computer monitor. Eventually I asked what was going on, and one of them explained the doctor I needed was driving over from another hospital.

After I’d waited an hour, the doctor arrived breathlessly, and I was given a 2-page form to initial in a dozen places as the doctor described all sorts of terrible things that could happen as a result of the procedure. I didn’t remember any of this from before. All I could think of was my poor mom, alone upstairs with no idea what was happening to me.

Finally they rolled me into the operating room, where a kid who looked like a teenage rock drummer started preparing me while behind my back, technicians fooled around with machines.

This went on for another hour, my stress rising to the breaking point. But when it happened, the procedure itself turned out to be anticlimactic – like before, uncomfortable rather than painful. My mom had left shortly before I returned to my room. She called later in tears – what a nightmare for her!

The results of the second lumbar puncture looked the same as the first, which the neurologists said was good news – things were not getting worse.

Final Days

Final DaysTuesday May 31 – Friday June 3

The physical therapist stopped coming, and during my final days in the hospital I walked around the unit alone, going faster and completing more circuits each time.

The young ophthalmologist returned to dilate my pupils and perform a final eye exam. He pronounced me normal except for a “weird texture” on my retina, about which he planned to consult some outside experts. But the exam itself drove my pain way back up the scale. I’d stopped needing dilaudid for the past couple of days, but now I had to go back on it.

A technician came to remove the catheter – a much easier experience than getting it put in. And finally, my sweats – the last of the original symptoms – simply stopped happening.

During the past few days I’d spent more and more time out of bed, either walking the halls or sitting up facing the outside world I hoped to re-enter soon. Despite still not knowing what had caused my illness, I was finally anxious to leave this place.

When we both agreed on discharge, the hospitalist arranged final summary visits from the neurology and infectious diseases teams. Both teams said the official diagnosis would be an HSV2 infection in the nervous system, but there was still no known explanation for all my symptoms, and they were still awaiting the results of many tests that took weeks to process. I learned for the first time that the female doctor on the neurology team was a subspecialist in neurological infectious diseases, and she gave me the name of a colleague at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix for any potential follow-up. She said to continue to treat lingering eye pain with oxycodone and tylenol, and it should eventually end. And if any HSV2 symptoms recur, I should go back on the antiviral.

Return to Life

Return to LifeSaturday June 4

At the end, there were forms to fill out and leave with the nurse. I had prescriptions that needed to be filled at the hospital pharmacy and picked up by the nurse. I still had IV sites on both arms that I had to track the nurse down and beg to be removed. I had to change from a hospital robe into my street clothes, for the first time in three weeks, and wait for an orderly to take me to the front door in a wheelchair. I had to call my brother for a ride.

I’d been attacked by mysterious forces which might always remain unknown. Taken out of my life, I’d been swallowed by a giant institution where I was largely helpless while being studied, often painfully and sometimes traumatically, by countless strangers – specialists in infectious diseases, pulmonology, neurology, rheumatology, nephrology, hepatology, radiology.

For three weeks I’d had no future, living only in the present. The raw data from tests had been reviewed, processed and presented to the doctors by inexperienced interns, so there was no guarantee that all of what I’d heard was accurate. Now that I was being discharged, I didn’t know if I was truly over it, or if symptoms would come back after I returned home.

The pulmonologists, who’d inserted a probe in my lungs and a needle through my back, studying me intensively, had never found an explanation for my respiratory failure. As a result, their treatments had only addressed the symptoms, not the cause. But still, I’d recovered – why? Could it happen again?

The specialists in infectious diseases, neurology, and rheumatology, who’d subjected me to painful scans and dozens of blood draws, had found the Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 in my spinal fluid – along with unidentified fungus. The virus could explain some, but not all, of my symptoms. They’d given me an antiviral, and while waiting to see if it helped, they’d tried to treat the fever with a cooling blanket and the pain with a high-dose steroid. The cooling blanket had worked but the steroid hadn’t relieved the pain, so finally I’d been given strong pain meds. The meds gradually brought the pain under control, so that after I was discharged, it remained manageable with weaker meds.

Was the pain now manageable because it was due to HSV2, and the antiviral was finally having an effect on the infection? No one could tell, but the infectious diseases neurologist warned that a recurrence was possible.

Leaving that hospital and riding to Mom’s house felt so strange – like being reborn, but as a much weaker and more vulnerable person. Would I survive? If so, how would I continue to change? Would any of those outstanding test results eventually come back positive, explaining my illness and raising new questions about my future?

I stayed at my mom’s house for 3 full days, resting and taking short walks, before taking on the daunting, all-day effort to travel back home alone. On those walks, I felt like a husk, a leaf, a feather, like a gust of wind could blow me away.

My 2020 house fire, and the continuing struggle to get everything back on track, should’ve proved that my life was largely out of my control, and could be ended without warning at any time. But apparently I needed still another, and more urgent, reminder.

Life is a miracle – let’s not waste it.

Three Weeks in a Hospital, Part 2

Monday May 16

In the ICU, a new nurse stuck wired probes on my chest and index finger, and attached a remote-controlled blood pressure cuff around my bicep. These all ran to a monitor screen on a tall stand near the head of my bed, so that with a stiff neck and eye pain it was almost impossible for me to see. But when I did manage to read it, I eventually figured out which line graphs and values indicated my pulse, blood pressure, and blood oxygen level. I was able to sleep that night, but by morning, despite the oxygen tube in my nostrils, my blood oxygen continued to drop.

The Infectious Diseases team had now faded into the background, to be replaced by an even larger team of pulmonologists. And they, along with the nurses and technicians, were seriously freaked out. They scrambled to switch me to high-flow oxygen through a mask, and more technicians were brought in to give me regular treatments of bronchodilators, also through a mask. At midday on Monday, one of the young pulmonology interns said my blood oxygen had reached a low of 84, and it was likely that I would die, so he needed my authorization on “Full Code” measures – painfully attacking my body with various machines in a last-ditch attempt to save my life.

Of course, both my comprehension and judgement were seriously impaired by my condition. I remember reluctantly agreeing to Full Code, after which, standing in front of the dry-erase board at the foot of my bed, the young intern demanded the name and contact info for my Power of Attorney. Fumbling with my phone, I found my friend’s number, and as I spelled her unusual name, he erased the center of the board and recorded the info there in red ink in huge block letters. And for the next three days, peering past the mask that was barely keeping me alive, all I could see most of the time was that bold red message that to me signified “YOU ARE GOING TO DIE!”.

Tunnel to the GraveTuesday May 17 – Wednesday May 18

For two days, I lay there breathing through the mask, enduring the clamor of the airflow, waiting for the next bronchodilator treatment. Staring at the red warning on the whiteboard, wondering if I would survive.

But the breathing treatments began to work, and my blood oxygen gradually improved. On Wednesday morning the pulmonology team returned, and their leader said they needed to perform a bronchoscopy – the insertion of a viewing scope though my mouth, throat and trachea into my lungs. This is normally done under some form of sedation, and the doctor said he planned to use ketamine, which would leave me semi-conscious but would keep me “calm” during the somewhat uncomfortable procedure. He said I would probably recover full consciousness with no memory of the procedure.

This was one time when I was briefed about a scheduled procedure – the hospital patient is not always warned. Much of the time someone just shows up to take you away for a procedure ordered by an anonymous doctor without any warning or schedule. Within a few hours, the machine was wheeled in, and the medication was administered, as the entire team assembled around my bed. I lost consciousness of the room, and instantly entered the nightmare.

Suddenly, I was pushed undergound into a dim, rocky tunnel. Dead grey rock surrounded me as a relentless weight forced me ever deeper. Always facing me was a dark wall crudely hacked out of stone, and the tunnel spiralled constantly downward avoid it. I’ve always loved exploring caves and mines, but this was completely different. This was an involuntary end-of-life experience.

I’d left the world of the living far behind, and the weight and pressure on me increased as I was pushed deeper underground. As much as it twisted and turned, there were no exit routes from this tunnel of doom – it only led deeper and deeper, and the rock walls became rougher and dirtier, with piles of rubble at their feet. This living burial seemed to go on forever, but finally it came to a definitive end – a blank wall of rough stone with more grey dust and rubble at its feet. The heaviest weight clamped down on me. This was the end of my life – I would never leave this filthy stone tomb.

I woke to a semicircle of shocked, fearful faces. The machine was rushed out of my hospital room, the doctor following with his eyes averted. One of the young interns stayed behind and timidly approached my bed. “I’m so sorry!” he said. “It was terrible to watch! Your arms and legs were thrashing violently during the whole procedure…”

Hours later the pulmonology lead returned, and unusually, took a seat next to my bed. “I’d like to apologize for what happened today. What was it actually like for you?”

He shook his head gravely as I described what I’d experienced. “I don’t think you should ever use ketamine for this procedure,” I said. “I agree – it was a mistake, and I’m truly sorry for what you experienced,” he replied. “However, we found a large amount of fluid both inside and outside your lungs – about 4 liters in total – and soon, probably tomorrow, we need to extract and test some of this fluid. The procedure, thoracentesis, involves inserting a needle through your back, guided by ultrasound, and it can be done here in your room.”

Needle in the Back

Needle in the BackThursday May 19