Max Carmichael's Blog, page 16

November 4, 2022

Desert Trip 2022: Prologue

Three and a half years had passed since I’d last visited my place in the desert, the place I’ve long called my spiritual home. That’s the longest absence in the 32 years since my Los Angeles friend and I bought the place, but the time span of three and a half years doesn’t begin to convey the changes I, and our society, have gone through.

COVID being the most obvious one, of course, and the reason why I didn’t visit in early 2000. But then my house caught fire, I was only minutes from dying or losing it completely, I had to shuffle between emergency housing for over a year, and repairs still haven’t been completed. Shortly after the fire, I had a near-death experience during a routine dental procedure. And this year, I was hospitalized for three weeks with a mystery illness and again came close to dying.

Since 1989, I had visited our land at least once a year, except for the years 2001 and 2002. That was also one of the hardest times of my life. Traumatized by the end of a relationship, broke and in debt after the collapse of my dotcom business, I’d begun reevaluating my whole existence. What had long felt like a spiritual quest now seemed an idle fantasy, and those remote desert mountains seemed irrelevant to my future.

But in 2007 I renewed my connection with the place by organizing annual campouts with others who love it, including several new friends – a new community brought together by our desert land. These eventually led to a more formal, conservation-oriented meeting in 2019, engaging scientists with Native Americans. I’d almost finished organizing the second meeting when COVID hit in 2020.

Why do I even own this place, and why is it so important to me?

Originally, in the mid-1980s, after falling in love with the desert and learning that people had lived there prehistorically, I gradually found myself wanting to live out there, off the land, like those prehistoric people. My artist friends and I had been camping out there throughout the decade, “domesticating” it for ourselves and generally finding it comfortable and pleasant as well as beautiful and magical. And as I learned more about the natural resources available, it seemed actually doable.

I took a course in aboriginal survival skills, and in spring 2002, after an unusually wet winter, I moved to my land and tried to survive. I relied on local water sources and began harvesting wild foods, but as most would expect, it’s not easy to go straight from civilization to a desert wilderness. And I had a girlfriend back in the city. So the desert would remain a place to visit, not to inhabit.

From the beginning, my co-owner and I had been telling people we wanted to be “stewards” of our land. On sporadic visits, we worked hard cleaning up trash and trying to eradicate invasive plants that conservationists said were destroying native habitat. But we were both struggling with jobs and relationships in the city and never had enough time to be real stewards in the desert.

At that last meeting in 2019, each of us spoke about how we came to love the desert, and what it means to us, and we each had completely different stories. In the end, it’s like asking: Why do people fall in love with each other?

Despite our early impression of comfortable camping, the desert eventually lived up to its reputation as a harsh mistress. Numbing, immobilizing heat in mid-summer. Sudden plagues of unknown insect pests that can drive you out of camp. Days of relentless, scouring gale-force wind that makes even the simplest chore an ordeal. Winter nights that freeze your water jugs solid.

I mentioned the prehistoric denizens, and my own failure to make the desert home. Does anyone actually live out there now? Not in our wild mountains, but a few diehard desert rats remain on or near the highway – like our local rancher, who lives in a house with indoor plumbing and electricity like the rest of us, driving to the nearest town for supplies. And the survivors of the last native inhabitants live similarly modern lives on their reservation, a few hours’ drive away.

Conservationists bemoan the damage caused to natural habitats and populations by industrial society: water sources fouled by domestic livestock like cattle and burros, fatal respiratory diseases spread to native bighorn sheep, riparian habitat degraded by invasive tamarisk, soil crusts trampled by off-road vehicles, underground aquifers threatened by commercial water development. I’ve heard scientists say the desert – or even the entire planet – would be better off if humans were completely eliminated.

A Different Kind of TripIn recent decades, as my focus broadened to the native tribes and their territory in the Southwest, I spent less and less time on our land and more time exploring other parts of that territory. Even though I allocated up to three weeks for these trips, driving hundreds of miles between states and mountain ranges stressed me out and left me with less time for camping and hiking.

I gave myself ten days for this trip, with no agenda other than simply to reaquaint myself with our land. It had been far too long.

Stuck in FlagstaffIt takes two days to reach the land, and Flagstaff is the midway point, where I typically stop for the night and shop for groceries and other supplies.

I’d spent a few hours on Saturday packing, and being out of practice, I’d forgotten how to protect my lower back when lifting the heavy water jugs, so I triggered my severe back pain and jinxed the trip before it even started. I knew it could only get worse since I would later need to lift the even heavier new ice chest in and out of the vehicle.

All my camping gear, except for sleeping bags, was new and untested, since my old gear had been destroyed in the fire. So another purpose of this trip was to test the new gear.

Late Sunday morning, after loading up, I started the engine, and felt it lurching and stumbling. There’d been no previous warning, so I shut it off and restarted. It seemed to be missing a cylinder, but it was driveable, and there was no way I was going to delay my trip another day to get it checked out locally. Maybe the problem would clear up as the engine warmed up.

Instead, the drive over the mountains to Flagstaff became a seven-hour ordeal. I faced a dramatic loss of power that required downshifting and revving to the redline to get up grades on the highway, and that was especially nerve-wracking on the interstate, under pressure from tractor-trailer rigs on a tight schedule and city drivers enraged to be caught behind me. And I was burning through fuel much faster, with gas prices that were already burdensome.

I made it to Flagstaff, but spent an hour Monday morning driving all over town trying to find a shop that would check my engine. The shop I finally found was downtown, but they couldn’t help me until afternoon.

Flagstaff is one of those Western boom towns that suffers from overdevelopment and hectic traffic. I’ve come to hate it, and strive to limit my time there to the bare minimum. But this time, I was stuck there for two days, most of which I had to spend wandering around town on foot, waiting for the shop to get started. My vehicle needed a tune-up, and parts had to be ordered overnight. And as a traveler from out of state, I was price-gouged by the shop.

I ended up walking loops around downtown, and out to the northwest along the Rio de Flag, a man-made drainage channel that features an artificial pond and riparian corridor. I spent hours one morning in the library reading from a surprisingly limited selection of magazines. None of my experiences made me want to return for more.

Finally, late Tuesday afternoon, I was able to do my shopping and hit the road, with only time enough to reach Kingman, a little over two hours west. By that time I needed to do laundry, in order to have enough clean clothes for a week of camping. So it was a third night in a motel – all in all, car trouble increased the cost of my already expensive trip by about 50%.

The whole time, I was suffering from back pain, wondering if and when it would immobilize me and require emergency treatment. And driving, hammering the accelerator to get up those grades, triggered my chronic hip pain. Was this simply destined to become another poorly-conceived trip from Hell?

My packing is always guided by a Gear List I started decades ago and have continuously updated, but I failed to update it before this trip, so there were some new developments, like a USB C adapter for my camera, that required a last-minute search in Flagstaff, and a few things I disregarded in my rush, like firewood, that turned out to be important once I reached the desert.

On the plus side, the forecast was for mild weather throughout my stay, with mostly clear skies and temperatures ranging from the high 40s to the low 70s. Unfortunately, this was the forecast for the nearest settlement on the highway, more than a thousand feet lower than I’d be camping, and I’d unconsciously stored it in my mind as the weather to prepare for – leading to some issues in the days ahead.

October 17, 2022

A Day in the Clouds

The world changes around us, and we must adapt. I’ve lost most of my high-elevation hikes to flood damage and debris in their canyon approaches, and I’m still not sure what to do about it.

This Sunday arrived with a forecast of rain all day, for the entire region. I considered postponing my hike and staying home – the vast majority of hikers avoid “bad” weather – but rain was forecast for Monday as well. And one of my main goals has always been to experience habitats in all conditions.

With the need to avoid flooded creek crossings, there was really only one remaining option – the crest trail east of town. I’d last hiked it less than two months ago, in late August – the trail had just been reopened after this year’s big wildfire, which had burned patches on the peak and destroyed my favorite fir trees. I wasn’t looking forward to returning, because overgrowth and fire damage had slowed me down then, and I expected conditions to be even worse now after much more monsoon rain.

Resigned to a day of frustration, I pulled on my waterproof pants and boots, and packed cool-weather accessories – the temperature was in the high 40s.

The sky was clear over town, but when I emerged from the pass into the eastern river valley, I saw that most of the crest ahead was blanketed by clouds. And nearing the top of the narrow, winding road, I entered the cloud layer, and the slopes around me disappeared.

This trail takes more than 5 miles to climb the 2,000 vertical feet to the 10,000′ peak, so the grade is mostly gentle, and for some reason I had a lot of energy and moved fast for the first 3 miles. This is normally a trail with continuous views far across the landscape to east and west, but today visibility ranged from 200′ to only 50′. I was all socked in.

Then my energy crashed, my legs seemed to lose all their strength and I suddenly felt exhausted. My fingers got chilled – Raynaud’s syndrome – so I pulled on wool gloves and stuck my hands in my pockets until they warmed. I’d been walking in a cloud all the way, and in the last mile before the peak, a light rain began to fall.

The rain only lasted about 15 minutes, and as I crossed to the back side of the peak, the clouds receded over me and I spotted tiny patches of blue above.

I’d seen horse poop on the way up, and their hooves had punched postholes in the wet dirt of the trail on the backside, making for tricky footing. Despite the wishful thinking of the Feds, horses and hikers are generally not compatible trail users.

In the big burn scar from the 2013 fire, on the western slope of the peak, I got my first view to the west, and could see storms developing and clouds flowing from canyon to canyon in the direction I was headed. And I discovered that the horsemen who’d made the trail harder to walk had cleared most of the thorny locust where the trail passes through thickets. So I was able to proceed faster than expected. Maybe I’d get to the rock formations, halfway to the far junction saddle?

Before I knew it, I was at the little saddle at the western base of the peak, where the trail marker tree had burned down.

At this first junction saddle, the horsemen had stopped and turned back, but after crossing the deeply eroded basin below, I found that another hiker had added tread to the trail down the narrow canyon since my August visit, so it was a little easier going.

I’d been walking downhill for over a mile now, and my energy had returned. And so had the rain, this time harder and longer. Making good time, I continued past the little saddle where I’d turned back in August, where the trail leaves the narrow canyon and passes to the west side of the crest. And since the trail gets better there, I shortly reached the first of the two rock formations. Would I actually make it to the next junction saddle?

The rain slacked off, and the hike seemed to go faster than ever before. I came to the long descending traverse, a corridor through Gambel oak, that leads to the saddle, and found a continuous trail of fresh bear scat, literally dozens of piles lined up in a row. I came upon a flock of band-tailed pigeons, flapping through the canopy, a hundred yards from where I’d first encountered these birds more than a decade ago. They’re hard to miss because their wings make a lot of noise. Then I suddenly emerged into the saddle, so smothered by the cloud I could barely see the forest on the other side.

More firs had been killed here by this year’s wildfire, and this saddle was no place to linger. But what a hike! I’d gone at least 9 miles – by the end of the day, I would’ve covered more than 18 miles and 4,500 vertical feet, far more than expected. And in the chill and the damp, my gear was working – I was warm and dry. Despite not being able to see out of the forest, I was feeling pretty happy about the way things were going.

On the way back up the narrow canyon, rain started again, harder than before, and this time it lasted all the way to the peak, more than an hour, as thunder crashed off to the west.

Approaching the peak, I developed a sharp pain in my right knee. It’s strange – for a decade, I had sporadic tendonitis in my left knee – that’s why I have multiple knee braces. But now, for some reason, it’s shifted to the right knee. Maybe it has something to do with the chronic inflammation in the left foot and the right hip. Ah, the joys of aging with an active lifestyle!

I toughed it out for another mile going downhill, then finally stopped to strap on my brace. But the brace didn’t help, so after another half mile of limping, I took a pain pill. That did nothing for the pain, but made me feel good in general, so I could ignore the pain, which is sometimes the way it works. Trying to discourage abuse, doctors often claim that pain meds don’t work, but the fact is that they help immeasurably even when they don’t eliminate the pain.

During the last two miles, it started raining again, this time harder than ever. It would continue for the next two hours, becoming a torrential downpour on the drive home.

It was getting really cold and I donned my storm shell under the rain parka, and my thermal cap under the hood. Here above 9,000′, after a day up in the clouds being rained on for hours – conditions most hikers would avoid like the plague – I was warm, dry, and despite the sharp pain in my knee, feeling great. Not even the low visibility could dampen my mood – I’d actually come to enjoy being socked in, surrounded by the gently flowing cloud blankets. Like the walls of a house, they temporarily obliterated the endless outer landscape, and I’d spent most of the day walking through interior spaces that felt intimate and, despite the storms, comforting.

October 10, 2022

Endless Monsoon

This year’s exceptional Southwest monsoon, which started early, in June, slacked off a little in mid-September. But then it resumed with a vengeance – the heaviest deluge in our local mountains occurred in late September, and in early October, with the onset of cool weather, we’ve turned into the Pacific Northwest.

Not that the Pacific Northwest doesn’t have its beauties, but that’s not what I moved to southwest New Mexico for! What a gloomy week. It started as I was in the midst of repairs on the outside of my house. Most of the work I’d planned for October would’ve occurred outdoors, and now all I wanted to do was lower the window blinds, collapse on the sofa, and read a book.

Sunday, my big hiking day, was forecast to be mostly cloudy but hopefully rain-free across the region. And I’d already decided to drive over to the range of canyons in Arizona, where I guessed it wouldn’t be quite so chilly, with even less chance of rain.

Hah!

Approaching the range from the northeast, I could see only light clouds. But once I entered the valley of the main creek, and started crossing bridges, I discovered it was in full flood, higher than I’d ever seen it. This range had been getting at least as much rain as we had, and it was plenty chilly here.

The part of the range accessible to me, this northeast basin, really only offers four choices of big hikes, and only two of those are interesting to me. I was tentatively planning to redo a version of my favorite, which involves driving a mile and a half up a really gnarly high-clearance 4wd track consisting almost entirely of big loose rocks. Fine, except there’s a creek crossing, and I wouldn’t know if it was too deep for my vehicle until I got there. And I didn’t think there was room to turn around at that crossing, which was at the end of the worst part of the road.

So I checked my maps and pinpointed the spot downstream where that creek met the graded spur road and emptied into the main creek, and slowed at that point to take a look. It was coming down pretty heavy, but I didn’t think it would stop me, so I continued.

Heavy rain had washed more dirt out from under and around the rocks in the road, so it was even rougher than usual. At the start of the really bad part, I parked and scouted on foot. It turned out the creek crossing had been widened, smoothed, and dammed at its downstream end with flat rocks by the original road builders, so even now, the flow was just shallow enough for my vehicle – no more than 8 inches deep. So I made it all the way to the trailhead.

Because the approach is so daunting, and impassable for most vehicles, this trail sees little use. I’d last hiked it in mid-July, and concluded nobody had been up it since at least May. But it does offer a popular short version, to the waterfall overlook, that is well-known enough to attract even novice hikers.

I made my way up the forested side valley, accompanied by the clamor of its little creek, collecting heavy dew from the chest-high overgrowth on my waterproof boots and canvas pants. But after crossing the creek, changing into my waterproof hunting pants, and starting up the switchbacks on the opposite slope, I got lost.

It wasn’t that I’d lost the trail – somebody had lost it before me, and spent a lot of effort thrashing about, trampling vegetation and creating spurious trails that got me so confused I couldn’t relocate myself in the heavy overgrowth of annuals on that steep, shrubby hillside.

Unlike my predecessor, I knew where the trail was supposed to be, so eventually, I just cut straight up the slope, and reached one of the switchbacks before going too far.

Like most of the trails in this range, it’s well graded for hiking, which means it has a narrow tread but generally neutral camber cut through the slopes it crosses. But with this kind of overgrowth, you often can’t see it and have to just keep pushing through the vegetation to reveal the tread ahead. My precessor apparently lacked the experience to do that, and immediately ventured off-trail when he or she couldn’t see the trail ahead.

It got worse, higher up the switchbacks. On the steepest traverses, instead of pushing through the overgrowth which leans across the trail from above, this earlier hiker crossed below, punching postholes in the wet slope, increasing erosion that undercut the original trail. At one point, they even created a new bypass above the original trail that was actually more difficult and further increased erosion.

Clouds had been closing in as I climbed above the waterfall toward the entrance to the hanging valley, the next phase of the hike. In the valley, there were still glimpses of blue sky and rays of sunlight that lit the aspen seedlings, now turning gold. I could hear the creek raging below me – the next question would be how passable it would be. The trail traverses down to the creek, where it follows the narrow bottom, crossing back and forth, for roughly a mile.

The canyon bottom was beautiful with this much water, and there are enough rocks that I was able to cross – 8 or 10 times – fairly easily. But it’s slow going. I keep wondering why this trail is so damn slow. It always takes more than 3 hours to complete the slightly less than 4 miles to the crest – a distance I can normally cover in less than 2 hours on other trails. On today’s hike I paid more attention, and settled on two factors: the mile following the creek, which is like an obstacle course, and the fact that much of this trail involves crossing small talus slopes which have been heavily colonized by shrubs, often thorny locust. There’s no way you can go fast across talus.

I finally made it past the creek section and began the traverse to the head of the canyon and the crest of the range. That’s when I was hit with my first hailstorm of the day – a fairly light and short one, but it brought with it colder temperatures.

I stopped at the cabin to take off my rain poncho and pull on a sweater, then I proceeded up to the crest, which is normally a wind tunnel. It was calm today, and the cloud ceiling was a few hundred feet above, leaving me a view across the plains to the southwest – one of the main payoffs of this hike.

In the saddle, at the junction with the crest trail, you can go left or right. I’d gone right in July, so it made sense to go left today, especially since the left choice offered more options. I’d arrived at the trailhead late today, so my time was shorter than usual.

The first, one-mile stretch of the crest trail is a continuous traverse, blessed by that amazing view. The aspen seedlings had turned gold all across the slopes, but the heavy cloud cover muted their beauty. And all along that traverse I could hear thunder from a storm far to my right, over the range’s western foothills. I could also see a storm forming directly ahead of me, and wondered what it had in mind.

At the next milestone, a junction saddle, I had a really hard time deciding where to go next. The most reasonable choice would be to climb the peak of the range, directly ahead – less than a half mile and a few hundred vertical feet. It was a dead end, so my return hike would be shorter and I’d have plenty of time to negotiate the obstacle course on the return to my vehicle.

But that peak is completely forested and offers no views – a total anti-climax – so I ended up taking the other option, and risked returning to the vehicle too late for dinner at the cafe and a room at the lodge.

Option two is a mile-long descending traverse around the western flank of the peak, leading to a small saddle with the potential to continue less than a mile for a view into the big southern canyon. Three different spectacular views in one hike – how could I pass that up?

It’s not the easiest traverse, crossing a broad, forested talus slope with big sharp rocks. But I made the saddle in good time, checked my watch again, and decided to continue to the viewpoint into the big canyon.

I was only a short distance below the saddle when lightning struck in the cloud directly above me, I was near-deafened by thunder and lashed by gale-force wind, and more hail started crashing down. After quickly pulling my poncho back on, I was barely able to snap some pictures across the head of the canyon, before rushing back up into the partial shelter of the conifer forest.

The storm followed me up to the junction saddle, and most of the way across the traverse to the head of the first canyon, lasting longer than most of our monsoon storms. But what a view!

I made good time on the crest traverse and the upper part of the canyon trail, running down smooth stretches, so that by the time I reached the creek, I began to think I might actually get dinner and a room tonight. And the clouds began parting, lighting up the aspens in the hanging canyon.

I’d been up this trail several times in the snow, and at this point, I could envision this once-in-a-lifetime monsoon simply transitioning seamlessly into a winter of heavy snow, with no break in between. We’ll see, but that would be something to remember, here in the arid Southwest.

I did reach the vehicle with plenty of time, although I used up the surplus time at the trailhead changing into dry clothes and footwear, so I had to literally bounce my little Sidekick down that rocky track.

Since so few people use this trail, later, when I had wifi, I checked trail reports on the popular Arizona hiking website, and found a report from early September. His story clearly suggested that he was the one who’d messed up the trail, and if so, likely left the trash I found in the hanging canyon. Not everyone who hikes is either skilled or conscientious.

October 5, 2022

DIY Front End Repair

At dusk, near the end of a 2-hour drive back from hiking in Arizona, I hit a deer head-on, about 10 miles south of town. My little 4wd Sidekick managed to limp home, as I took back streets to avoid drawing attention to the smashed headlights. But only a block from home, engine temperature reached critical and smoke started pouring out of the engine compartment.

April 8: Surveying the Damage

April 8: Surveying the DamageI’d killed a large animal, with the vehicle I rely on to get to my land in the desert, and to go hiking in the mountains every week – some of the only things that make my life worth living. I was in shock, literally traumatized, for days afterwards. But there was still coolant in the radiator, and I was able to drive across town to the local body shop.

Unfortunately, they couldn’t source most of the necessary parts for my old vehicle, but they estimated that if they could, repairs would cost $4,200, more than the vehicle is worth.

Most people I know drive late-model vehicles and maintain collision and comprehensive insurance for situations like this. But I haven’t been able to afford those luxuries for decades, and in any event, you don’t carry anything but liability insurance on a cheap 27-year-old vehicle. And unlike my more “successful” friends and family, I can’t afford to replace my vehicle with something new every few years.

So I was pretty depressed. Finally I began pulling things apart, surveying the damage, and doing my own searches for parts.

The deer was sideways when I hit it, its body stretched across the width of my vehicle, so the damage was fairly uniform across the front. The upper part of the front end, which had been convex, was pushed inwards. The grille exploded, the headlights and A/C fan were smashed, and the A/C condensor and radiator were driven back towards the engine, where the cooling fan housing impacted the fan belt.

I initially thought the radiator was okay, but later found there was a slow leak, probably from impact against the condensor.

In my 20s and 30s, I worked on my 1965 VW Beetle, rebuilding the engine and the front end. But I hadn’t tackled anything like this before!

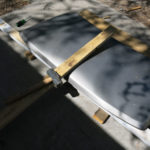

April 8 – April 13: Straightening the Frame

April 8 – April 13: Straightening the FrameOf course, I was able to find a few helpful YouTube videos on repairing this kind of damage. I’ve always kept a come-along – a hand winch – for my desert trips, and I picked up some heavy-duty nylon straps at our new Harbor Freight. Luckily I had an invasive elm tree along my driveway in back that I could use as an anchor. I’ve since had it removed, so I better not hit any more deer!

The front cross-member that was bashed in is called the upper radiator support. It’s not a structural member, nor does it actually support the radiator – it just spans the space between structural members on each side, and holds the horn and the hood latch. But because it was smashed in along with the structural parts it bolts to, I had to straighten it all in place. It’s normally convex, and I used the straight edge of a board to determine how much I needed to pull it back out, winching successively at a few different points to approximate the original shape.

The impact with the deer drove it back a maximum of 3 inches, and I was able to pull it back out about 2-1/2 inches. The vehicle has a tube frame, and the longitudinal tube on one side was slightly compressed by the impact, which made it impossible for me to completely pull the crossmember all the way back out.

As you can imagine, bending all this steel was extremely difficult, and took several days of blocking my tires, setting the handbrake, winching and letting the vehicle sit for hours under tension. Then releasing it, checking the displacement, and starting all over again. But the amount of restoration I was ultimately able to achieve was adequate for everything inside to fit and function properly.

April 13: Straightening the Hood

April 13: Straightening the HoodIn a big city, a person with modest means trying to fix this kind of damage would head to a junkyard for salvage parts. But here, the nearest yard is a 2-hour drive away – with a decent selection almost 3 hours away in El Paso – and any body parts I found would be in the wrong color. I wanted to try bending and beating things back into shape as best I could.

The hood was really tricky – light gauge metal but stiffened by welded cross-bracing – so I had to try a series of different wooden “jigs”, using a sledge, clamps, and my body weight, to straighten out the compound curves that had been deformed. The impact had broken a bolted-on hinge, and I was able to find that online, along with everything else that I couldn’t fix.

April 14: New Headlights

April 14: New HeadlightsThe formed sheet-metal framing around the headlights had been pushed in, and had to be pulled back out. But new headlights were readily available online, and when they arrived, the hardest part turned out to be aligning them. The screws were really hard to adjust, and I didn’t have a level space facing a wall to shine them on, and compromised with my sloping driveway and the front wall of the casita.

I live in the middle of nowhere – it’s not like most people around here are going to notice the difference…

April 19: New A/C Fan

April 19: New A/C FanI replaced the fan before discovering the radiator leaked, thinking I might be almost done! And then I got sick…

June 29 – July 14: New Radiator

June 29 – July 14: New RadiatorAfter I got out of the hospital, and began to recover my strength, I ordered the new radiator.

A radiator is a tight fit! It took a lot of wiggling and jiggling to get it to slide all the way down in its channels, between the A/C condensor and the stiff plastic fan housing. Everything around my old engine is slathered in oil, so working with mounting bolts and hoses underneath was a messy job. And there was a lot of stuff in the way, resulting in bruised and scraped knuckles.

Meanwhile, I realized I should replace the thermostat too, so I had to put everything on hold until that arrived.

Then, I had to flush the cooling system, which took another couple of days. Unbelievably, everything I replaced worked right off the bat, and there were no leaks in the cooling system. The new thermostat even seemed to fix the engine surging problem I’d had for years!

July 14–15: New Grille

July 14–15: New GrilleThe new plastic grille was one of the cheapest parts – $30. After I screwed it on, I realized the hood needed some more work – the panel gaps at the sides were annoyingly big. I used a ratchet strap to bend it down a little more. Then I really thought I was done.

October 4: New Horn

October 4: New HornThe use of car horns is strongly frowned upon here – it’s considered the height of rudeness. And traffic is blessedly light anyway – most of my driving is out on the open highway, where I can go a half hour or more without even seeing another vehicle. So it was a while before I realized my old horn wasn’t working. No surprise – it took a direct impact in the collision. Like other parts, hard to pick the right one online, but easy to install.

[image error] October 4: Good Enough for NowAs you can tell, I was only able to work on this project sporadically over many months. I had a lot of time to reflect on what I was doing, what others weren’t doing, and what I might rather be doing with my time.

I often thought I would rather be working on my visual art project, or my music, or my book. But I realized that, although I grew up in a culture that valued craft and manual labor, at this point, I don’t know a single other person who would consider repairing their own vehicle. Not a single person – correct me if I’m wrong!

Most people I know have newer vehicles that are so automated and computerized that many of their components can’t even be repaired by specialists, and must be completely replaced when they fail. But even if their vehicles could be repaired, most people have long renounced the necessary skills and tools, perhaps believing that their superior intellects and educations entitle them to live off the manual labor of others – the proletariat romanticized by the highly educated Bolsheviks.

Even when I’m not working on the old Sidekick, I’m aware that everyone else in my unusually diverse neighborhood has newer vehicles – except the old hippie couple down the street, who cover their windows with insulating panels to save energy, and drive a dilapidated van from the 80s.

The fact is, I don’t want an automatic transmission, or power windows, or cruise control, or GPS, or cameras on the outside of my vehicle – and especially not a damn touchscreen!

I’m sure some of my neighbors are embarrassed by the old, obviously damaged vehicle sitting in my driveway. I’m glad I don’t need to rely on an automotive status symbol to prove that I’m a success. And even at my advanced age, I can agree with the young Harlan Hubbard that “I wanted to do as much as I could for myself, because I had already realized from partial experience the inexpressible joy of so doing.”

October 3, 2022

Saving the Day

What a day.

When I got up in the morning, my two choices were to drive to Arizona for a hike that didn’t interest me, or to revisit a hike closer to home that I’d done only two months ago, and take a branching route that had never interested me. I chose the latter.

This was my third drive up the west side of the mountains in three weeks. Last week, I’d discovered there’d been catastrophic flooding on the west side that had taken out the canyon trails. Today’s trail didn’t follow a canyon, but the access road did cross the biggest creek in the range. I didn’t think the crossing would be a problem, because the creek had a very wide channel there, and the water level would be low enough for my vehicle by now.

Approaching the creek, the dirt access road enters a shady sycamore forest, emerging abruptly into the light to descend a steep bank into the creekbed. It’s a good thing I was driving slowly, because the road ended suddenly in a four-foot drop-off, and the creek, which had previously been about 15 feet wide, was now more than 60 feet wide. A huge amount of water had come down, recutting the whole broad channel. I assumed the ranch on the other side of the creek had another access road, because they weren’t going to be using this one for a while.

Nor was I. My choices of local hikes were rapidly diminishing, and it could be years before most of those trails were salvaged, if ever. I turned around and drove out to the mesa road, where I stopped to ponder my options to redeem this ill-fated day.

There was really only one that didn’t add a lot of driving. I could continue up the mesa and re-do the hike I’d done only two weeks earlier, that had ended at a swimming hole. I hated to repeat a hike I’d already done so recently. And it would involve a creek crossing that had surely been devastated by flooding, but at least the creek would now be low enough to cross.

And there was a possible way of putting a new spin on that hike.

The day had started clear and cool, but the forecast was for partly cloudy skies and a chance of rain in town, which meant I had to dress for rain in the mountains. Dark clouds were massing over them as I drove north to the next trailhead.

And at the bottom of the long traverse into the canyon, I began to glimpse fallen trees and a new debris flow in the bottom. The flood had pushed shattered trees way up the bank on each side.

I crossed the rushing creek and found a logjam hanging six feet above the current creek level on the other side – that’s how high the flood had reached here.

Drifting clouds kept changing the landscape from sunlight to shadow as I climbed the long switchbacks, turned into the long hanging valley, and trudged up the steep trail of loose rock to the little peak at the start of the rolling plateau. There, the broad vista of the western edge of the wilderness spread before me. But it was the ridge in the middle of that view that interested me.

As I continued east across the plateau, I had my eye on the series of rock outcrops and peaks that punctuated that ridge. For the past two years, on every hike along this trail, I’d dreamed of bushwhacking up that ridge. It seemed to offer views into the deep, rugged canyons on both sides, but it clearly had very steep sides, which would need to be traversed to bypass sheer cliffs, and some of those slopes included dangerous talus.

All summer, while recovering from my illness and finding my lung capacity reduced, I’d avoided the challenge of bushwhacking, while sticking to trails I believed to be in good shape. But today, I was finally in the proper mood. I’d made a false start and the day was too advanced to try one of my marathon trail hikes, so why not go exploring off trail?

The best approach to the ridge was hard to judge. The north edge of the plateau seemed to lead more or less directly up that ridge, but the lower part of it was densely forested, and that forest could hide a lot of arduous ups and downs.

Previously I’d assumed the best way up would be to follow the trail to the saddle above the next canyon, then turn left and bushwhack up a low ridge that seemed to lead directly to the higher ridge.

But now, after descending partway into the hollow below the saddle, I realized the trail would add a lot of distance that I might be able to avoid by taking a short cut from here, completely avoiding the saddle and its low ridge.

This did involve crossing an intervening gully, and traversing around a rocky bluff, but what surprised me was how quickly I could gain elevation when I didn’t have a trail to follow!

My lung capacity was still limited – I had to stop a lot to catch my breath – but for most of the hike to the ridge, I was just hiking straight up the slope, which varied between 30% and 45% grade. That gets you a lot of elevation, and some great views!

The rock underfoot was also rapidly changing, from pink to orange to white. I hadn’t thought about it much at the start, but one of those distinctive outcrops became my first milestone, and it turned out to be even more interesting than I’d expected.

Just before reaching the big outcrop, I came to a little ledge featuring a couple of wind-sculpted junipers – a dead one and a live one that offered enough shade for me to rest a while and enjoy a snack.

Afterwards, continuing toward the first peak of the ridge, I noticed what seemed to be a cave on the up side of the outcrop. Sure enough, some hiker in the distant past had stopped there, accumulating a pile of firewood that seemed excessive, considering no one else had reached this spot in ages.

The peak I reached afterward had some great views of storms developing over the region, but it was only a temporary stop. I had my eye on two little peaks higher up that blocked my way to the long “hogback” in the middle of the ridge, which bore an attractive fringe of tall ponderosas.

Unfortunately, the first of those two little peaks turned out to consist completely of talus – large, sharp, loose rocks – colonized by dense thickets. And while I was fighting my way through that, a light rain began to fall. Hanging to the branches of shrubs on that perilous talus, way up in the sky, I climbed precariously to within a few yards of the peak, then scouted a few dozen yards to left and right for an easier route around, only to conclude it was just too dangerous to continue.

My way up the ridge was blocked.

I hadn’t gained the desired view into the big canyon to the north, but I wasn’t really disappointed to turn back. I’d bushwhacked over a mile on steep slopes, climbing a thousand feet above the trail, discovering a shelter cave. Not too shabby for an old guy recovering from a long hospitalization.

As I scanned the landscape around me, I noticed a flash of white farther down the ridge – it was a white-tail deer bounding from rock to rock, mostly hidden behind tall scrub oak. I was really surprised to see it atop this steep, rocky ridge – not typical deer habitat.

I fought my way down to the rise above the rock outcrop, and paused for a few minutes to consider my return route. The way I’d come up was known, but there was also the possible route to my right, down the arcing extension of the ridge I stood on, which seemed to connect to the rolling plateau in an area of dense forest and shrubs whose topography was unclear. It was a hard choice, but in end my mood spurred me into the unknown.

The first part of it, down an open slope of grass and low shrubs, went incredibly quickly – I could even run down in some places. But when I reached the trees, it got more complicated.

I somehow managed to avoid gullies, but near the bottom, I found myself in open forest blocked by a maze of scrub oak, mountain mahogany, and manzanita that I just had to push through for a long distance, trying to hang onto my sense of direction to avoid missing the plateau.

Hence it was a big relief when the shrubs suddenly opened ahead of me, revealing a cairn and the plateau trail.

Clouds were still moving all over the landscape, alternately threatening rain or highlighting slopes and rock formations, as I returned across the plateau. And the flies, which had deserted me up on the high ridge, began to swarm me again.

About a third of the way down the switchbacks, some serious rain began to fall, but it cleared before I reached the bottom. And the climb out of the canyon to the trailhead, which usually finds me sore and exhausted, seemed a lot easier than usual.

I couldn’t remember a recent hike that had made me this happy.

September 25, 2022

Total Washout

The day before, I’d driven a half hour east of town to attend the harvest festival that I started when I first moved here, in 2006. I was truly grateful to see it resurrected two years after the start of COVID, with a new generation of volunteers to keep it going.

A few of the old-timers are still around, too, and it was good to see them. But everyone else was just a stranger.

After forcing down a mediocre lunch prepared by one of the food vendors, and after enduring a mediocre performance by what used to be called a folk singer and is now called a “singer-songwriter”, I discovered that the mother-daughter country gospel act had canceled due to a family injury. And I realized that they were the only reason I was there. I’d been in charge of “entertainment” – everything from oral history and poetry slams to music and the announcing of prize winners – and they were one of the first acts I’d hired, and my personal favorite. In their honest, angelic voices, they’d delivered the songs I grew up with in the Appalachians.

So I left early.

I devoted hundreds of hours to that festival, and I’m still proud of it, although it’s no longer part of my life. It now seems to be self-sustaining, and it’s the only event in that rural valley that brings everybody together, once a year.

That night I tried to figure out where to go on my Sunday hike, and was stumped. I had a busy week coming up and didn’t want a long drive or an overnight, but most of the nearby hikes were undesirable due to monsoon overgrowth.

I woke up in the morning completely unmotivated and could barely get out of bed. I’d found a recent online trip report from a trail over in Arizona that I really wanted to try, but it would involve 5-6 hours of driving and an overnight, so it was out of the question right now.

After delaying my start to make up my mind – and almost giving up – I finally made a decision, and hit the road late. I would drive an hour and a quarter northwest and take a slow, overgrown canyon trail up to a high saddle, where I could cross into a more remote canyon and eventually reach the confluence of two big creeks. The latter part of the hike would offer some epic views.

I’d hiked the first canyon ten times in the past four years, but always found it maddeningly slow – the rampant vegetation, the debris flows, the random piles of logs, the continual detouring around giant boulders, the dozens of creek crossings. Really, the only reason I ever came back here was for the views you get once you climb out of the canyon to the crest. I had only made it to the remote confluence, in the farther canyon, once before. Out and back, it would be a little less than 13 miles and 4,000′ of elevation gain.

Driving north up the highway into the valley of our famous wild river, I saw signs for the river festival, and realized it was also on this weekend. It’s organized by our local environmental non-profits, and features conservation-oriented lectures, panel discussions, field trips and workshops.

I’d volunteered and attended several sessions at the river festival in my first year here, ultimately deciding that something more subsistence-based and inclusive – like my harvest festival – could be more effective for both land and community. The river festival is just preaching to the choir – the liberal retirees and idealistic youth that always temporarily patronize this sort of thing, but seldom put down roots in this land or this community.

I reached the turnoff for the trailhead, and discovered that the little creek was flowing vigorously out of the foothills and past the highway, something I’d never seen before. And I quickly found that the long gravel approach road had been washed out by debris flows at many places – something that should’ve tipped me off even before reaching the trailhead.

The road was in such bad shape it took me twice as long as usual. And at the trailhead I was surprised to find two vehicles – only the second time I’d had company here. According to the log, there was a birder from Arizona – he wouldn’t go far! – and a party of two planning the same remote destination as me.

Like most of these west-side trails, it traverses down into the canyon first, then continues upstream a few miles to the base of switchbacks that then lead to the crest. In this case, it’s 3/4 of a mile from trailhead to first creek crossing, and that’s where I had my next surprise. The canyon bottom had been scoured by a very recent flash flood – probably in the last couple of weeks – that had brought down tons of debris – rocks and shattered logs. The creek was roaring along but was precariously crossable on submerged rocks thanks to my waterproof boots.

But the farther I went, the less trail was left. What made this trail bad to begin with with – the narrowness of the canyon forces it to stay in or near the creek – means that when there’s a bad flood, the trail just gets wiped out, and the going gets very tough, since you have to find your way over, under, or around an obstacle course of shattered logs and boulders while trying to stay out of the rushing, foaming water.

I kept thinking of the other hikers ahead of me. Surely I would meet the birder soon – they typically stop after only a short distance to watch and listen for birds. But although their footprints were everywhere, they all must’ve gotten a much earlier start than me. I was beginning to feel like a real loser.

In the end, I made it less than a mile and a half before giving up. The general outline of the canyon I knew so well was still there, but the canyon-bottom trail was completely gone, and I had no desire to spend my day in this congested, scrambled up place. It had become such a brutal scramble, I couldn’t believe the birder was still ahead of me. I was sure the party heading for the high saddle and the remote confluence would not make it – it would take them most of the day just to get through this apocalyptic canyon. Presumably they were young people who would just embrace the challenge.

I remembered a party I’d gone to in 2008, where I met a guy returning from a hike on this trail. The original trail ascends over 4,000′ to the crest of the range, passing an iconic 10,600′ peak and connecting to a broad network of crest trails, but that network has been completely abandoned since the 2012 wildfire.

The guy I met had been part of a large group of young people who set out to reach the iconic peak, a round-trip hike of 18 miles and over 5,000′ of elevation gain. He was older than them, and gave up and headed back as the sun was beginning to set. He arrived at the party around 9 pm, sore and exhausted.

The others continued, scrambling on dangerous talus slopes well after dark, returning long after midnight – the kind of adventure many of us have had in our youth.

Back at my vehicle after only two hours of hiking, I tried to think of another nearby option for the remainder of the day. But they would all require long backcountry drives and would likely have experienced the same amount of flooding and disruption. Most of my high-elevation hikes are in this area – would all those trails now be lost? It would take a huge effort to rebuild them – an effort I doubt will be practical. This was the worst flood damage I’ve seen in this area in 16 years.

This Sunday’s hike was a total washout.

[image error]

September 19, 2022

The Rainbow at the End of the Swimming Hole

I wasn’t looking for a swimming hole. And I certainly wasn’t looking for a rainbow. I wasn’t even that excited about going for a hike, although I knew it would be good for me.

The night before, I’d pretty much decided to do my old favorite nearby trail, but it’d been less than two months since I’d last hiked it, hence my lack of enthusiasm.

The day was supposed to be partly cloudy, with rain possible in the evening, and there would be creek crossings. So I had to wear my waterproof boots again, and pack my rain gear – as with every damn hike since late June.

It was cool enough in the morning that I had to wear a jacket, but I stopped halfway through the one-hour drive to take it off.

This is the hike that drops into the first canyon, crosses the creek, climbs 1,400′ on switchbacks to cross a rolling plateau, and finally drops 1,200′ into the second canyon. And although I think of it as my favorite nearby hike, it’s one of the hardest on my list, because of the several very steep, rocky sections that are especially brutal now with my reduced lung capacity.

Recent hikes had been fly-free, but they reappeared with a vengeance in the first canyon bottom, and kept swarming me all day, so I had to view everything through my head net. Fine, it in no way obstructs my vision, but it does get sweaty, and this was another sweaty day.

Unusually, there was another vehicle at the trailhead, a bashed-in Kia Soul from Wyoming all plastered with outdoorsy stickers. But the only tracks on the switchbacks out of the first canyon were from horses – the Wyoming visitor(s) had gone up the abandoned canyon trail.

The horses had been here some time ago, and I knew it had to be my nemeses, the shrub-and-tree-hacking Backcountry Horsemen.

One alternative I’ve long considered here is to bushwhack up the high ridge between the two canyons, instead of dropping into the second canyon. The ridge is steep and punctuated by dramatic rock formations and talus slopes, so it’s probably extremely challenging.

Crossing the plateau, I kept eyeing that ridge. It would give me great views, and a return hike that would be all downhill, as opposed to the brutal climb out of the second canyon.

But when I reached the decision point on the saddle overlooking the second canyon, I chose to go down. A guaranteed dip in the creek seemed a decent trade-off for the harder return.

[image error]

[image error]

The horsemen had gone crazy on the trail down into the second canyon. This trail had been clear of brush to begin with, so they’d widened it into a 10′-15′ clear-cut corridor. But there was nothing they could do about the loose rocks and 30% grade. Despite all the effort they’re putting into it, it appears to me that the only people using this trail are the equestrian trail crew and me.

The hike to the canyon bottom isn’t long enough for me, but the continuation up the other side is too long for a day hike, so by the time I reached the creek, I’d decided to give the old, abandoned trail up the canyon another try. Last summer, on a much hotter day, I’d gone about a half mile up and found a tiny, debris-filled swimming hole.

Today, I discovered the horsemen had hacked their way to that same place, then given up. So I used my bushwhacking skills to trace the old creek trail farther up, helped by occasional cairns and pink ribbons.

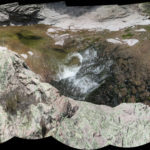

On the way, keeping track of the creek in gaps between trees, I noticed a possible swimming hole. And when the trail finally ended in a debris flow, I headed back there.

I’ve been to some great swimming holes, but this one has to make the all-time list. There isn’t a pool big enough to actually swim in, but it has bathing completely covered.

For over a hundred feet, the creek flows over bedrock – the ubiquitous white volcanic conglomerate – and over time, it has carved tublike hollows on its way down a gentle grade. The upper stretch is flat, then it pours over a little falls into the first pool, which leads into the second, which is bathtub-shaped and about 4-1/2′ deep. The overflow goes over another flat stretch and into a larger pool that’s at least 6′ deep.

When I stopped downstream in July, the water was barely cool, but now it’s actually cold! Too cold to stay in – probably in the mid-to-low 40s. This amazed me, since our night-time temps in town haven’t dipped below the high 50s yet. But the source of this creek is all above 9,000′.

After my first dip in the bathtub pool, I noticed there were fish in there. When spooked, they would spill over the flat stretch into the downstream pool, then shimmy their way back up.

I only stayed long enough to rinse my sweaty clothes and take a couple of icy dips, but when I started to dress I discovered my Raynaud’s syndrome had kicked in for the first time since last winter, and my fingers were yellowish-white, numb, and tingling, barely functional. And it was getting cooler in the canyon – the high fishscale clouds of morning had been underlaid by thunderstorm clouds which were spreading and casting occasional shade.

The one-mile climb out of the canyon was as bad as expected, and took an hour. Most of the way up, there was a voice in my head whispering “Just give up. Just lie down and die. This is not worth it.” This is the price you pay for the dip in a wilderness swimming hole. My fingers didn’t get back to normal until after I’d gone most of the way back up.

My right knee had been complaining on downhill stretches, so after re-crossing the plateau I strapped on my knee brace for the descent into the first canyon.

With my stop at the swimming hole, and especially with having to go slow on the steep sections, it’d ended up taking me 9-1/2 hours to go 14 miles, with 4,100′ of accumulated elevation gain. And there were more delays on the drive home.

I’d no sooner started driving the badly eroded ranch road down the mesa – with the sun lowering behind distant cloud layers toward Arizona – than I noticed a partial rainbow over the mountains to the south.

I could see rain obscuring the far south, where I was headed, and as I continued down the mesa, the partial rainbow acquired a faint double.

Where the road drops down off the mesa there’s a good spot for a scenic view of the river valley and the south end of the wilderness, so I pulled over and got out. And saw the whole rainbow, arching over the valley!

From then on, it was a show of clouds and light, even after dark, and I drove home through scattered showers. I got home way later than usual, for dinner and a shower, but it was worth it.

September 12, 2022

Stalked by a Hawk

Last Sunday’s hike had involved a long drive and an overnight, so today I wanted to stay closer to home. But many of my favorite crest hikes could only be reached via a canyon-bottom trail, and after our wet monsoon, canyon bottoms had turned into jungles.

There was one crest hike very close to town that I hadn’t tried since my recovery, because it started with a “primitive” road up a narrow canyon with at least a dozen crossings of a perennial creek. And on my last visit, shortly after the start of the monsoon, the creek had flooded so high it couldn’t be crossed on foot.

But our rains had slacked off recently, so I figured I’d give it another try.

This is the longest of my day hikes – 18-1/2 miles out and back, with 4,400′ of accumulated elevation gain. The only reason I can achieve that much mileage in a day is because the trail’s in better condition than any others – most of it follows the Continental Divide Trail, which is completely restored annually, as opposed to our national forest trails, a few of which are only partially cleared at much longer intervals, with the rest completely abandoned.

On the down side, with the exception of one short canyon passage, it’s the least spectacular of my hikes. You’re mostly hemmed in by forest, and when you’re not, you’re crossing burn-scarred slopes with only nearby views of featureless forested mountains. I end the hike at a “park” – a shallow bowl on the crest of a ridge with tall ponderosas around the edge and a grassy clearing in the center.

The hike starts at 6,600′, following the primitive dirt road eastward up the canyon for two miles. The creek was running briskly, but my waterproof boots made all the crossings easy. Spectacular rock formations rise on both sides but are mostly hidden behind the trees, until you reach the mid-section, where the canyon narrows and the road becomes steep bedrock, with the creek pouring down it.

Here, I found the road completely destroyed by erosion. Not even the ruggedest and highest-lifted Hummer or Jeep Wrangler could get up this road now – there were multiple 3-foot-high ledges and 3-foot-diameter boulders blocking the narrow passage between shear cliffs.

I recalled the day a couple of years ago when I’d met a young couple from California who were hoping to view a property at the end of this road, high in the forest. The road had been barely drivable for my vehicle then, with 4wd and 9″ ground clearance, but they’d made their way up to the midsection in a Prius, finally giving up and hiking the rest of the way. I wondered who owned that property now, and what they would do with the road, if anything. It’s simply a misconceived road in the wrong place.

Less than a mile up the “road” past the midpoint, you reach the hiking trailhead. From there, you wind and switchback up the densely forested side of the canyon to a long level ledge through parklike forest. That takes you to the upper part of the canyon, where the trail rejoins the creek and climbs steeply to a forested saddle where it joins the CDT.

The CDT crosses eastward to another densely forested watershed, where it traverses in long switchbacks up a south-facing slope to the 9,000′ peak. Apart from short rocky sections, this is mostly a smooth forest trail on packed dirt, so I was able to make good time.

Northwards past the peak, the trail reaches the edge of the 2014 wildfire, dropping toward a saddle through alternating burn scar and surviving stands of mixed conifers. Here, I found very fresh bear sign, then suddenly came upon a young couple hiking up from the saddle, where the trail meets the gravel road to the nearby fire lookout.

The young woman was busy leashing a medium-sized black dog, but what immediately caught my eye was the black cat wrapped around the young man’s shoulders. “Wow, you’re the first hikers I’ve ever seen with a cat!”

“That’s right, ignore the dog, he’s used to it!” said the girl, laughing.

We had a brief, friendly chat, while the cat on the guy’s shoulder fixed me with an intense stare. They seemed anxious for more, but I felt like I was running out of steam and wanted to keep my momentum.

Shortly after leaving them I felt a shadow passing over and figured it was a vulture. Instead, I saw a large hawk just settling into an upper branch of a low snag next to the trail, to peer down at me curiously. We watched each other for a while, then I continued, finding the couple’s vehicle at the road, with a New Jersey plate.

Past the saddle the trail begins traversing further east around a series of rounded slopes through moonscape burn scar which has filled in with shrubs and annuals. Here I was joined by the hawk again. Why? Normally a hawk will only pay attention to a human if it has a nest nearby, but this hawk was stalking me a quarter mile from where I’d first seen it.

As usual at this time of year, the annuals on the slope were at their peak of flowering, but hard to photograph. Nearing the intact forest after another half mile of traversing, I was amazed to find the hawk again joining me, briefly. I guess it was just curiosity!

The trail crosses into yet another big forested canyon, where it continues to traverse the head, just below the crest, descending gradually toward a saddle on the eastern rim. At this point I was really fading. My legs and right hip were burning and I was deeply fatigued. I’d only gone between 7 and 8 miles – how would I make the full 18-1/2? I stopped to stretch my hip, and that helped a little, but I was still worn out. Then, nearing the saddle, I came upon recent cattle tracks. Great.

But I’d come this far – I had to reach the park. Once there, having finally crossed to the north side of the long ridge, I didn’t continue to the grassy center – I collapsed on pine needles in the shade of the big ponderosas and Gambel oaks.

I lay there for a long time, knowing it was getting late, but figuring the return hike would go faster since it was all downhill past the peak.

Finally I forced myself to get up, and trudged back out of the park and over the crest. On the long traverse back toward the road saddle, after another session of stretching my sore joints, I took a pain pill, and by the time I’d reached the road I was feeling good again.

Surprisingly, the New Jersey van was still there. And just as I reached the top of the traverse to the peak, I glimpsed them through the trees ahead, and their dog shot forward barking hysterically and threatening me.

I was making good time, so at this encounter, while the woman struggled to subdue her young dog, we talked even longer. Despite the Jersey plate, they’d been living in town for a year, cobbling together miscellaneous jobs. They hoped to see me again later.

I was really feeling much better as I strode down the mountain, smiling and spreading my arms to stretch my shoulders. I hadn’t seen any recent footprints on the CDT, but when I eventually reached the creek trail I began to notice occasional mountain bike tread, and when I finally reached the upper part of the dirt road in the canyon bottom, I realized two people had ridden their mountain bikes here while I was hiking. Then at the rocky midpoint of the road I found footprints of another couple who’d walked up today. And just past the eroded, undriveable part there were off-road-vehicle tracks and horse poop, also from today. Apparently there’d been a whole crowd down here on every conceivable conveyance while I was up higher hiking. Nice to be able to get away from the riffraff!

September 5, 2022

Blowin’ in the Wind

It was September already, and there was only one of my regular crest hikes that I hadn’t tried since my May-June illness and loss of capacity. It was in the range of canyons over in Arizona, southwest of here, and was far enough that it involved an overnight stay.

The last time I’d been up there was the end of January. We hadn’t had much snow, but there were some drifts that had enabled a test of my new waterproof boots.

Now I was wearing those same boots during the summer monsoon, to help with creek crossings and fend off rain. It appeared that our thunderstorms were on the wane, but I brought the boots anyway, and was glad as I saw a layer of clouds over the mountains ahead. Then I remembered the creek crossings at the beginning of the trail, sometimes a challenge even at low flow, and was doubly glad.

The first half of the hike involves a steep climb from a lush riparian corridor at 5,800′, deep in the central basin, to a “pine park” at 8,000′, up on the shoulder of one of the range’s tallest peaks. It starts with three crossings of the range’s most famous creek, which turned out to be running high as expected, and up to 15′ wide. Trusting in my boots, I basically just ran across on submerged rocks, but at the second crossing I encountered a father and son who were wearing sneakers, and I helped them find a stick to make their crossing safer.

Despite it being a holiday weekend and this being a popular getaway from Tucson and Phoenix, I didn’t see anyone else after that. The 2,000′ climb from oak scrub to mixed conifer forest is very steep – when I started hiking here 3 years ago I considered it one of my most daunting climbs – so with my current reduced lung capacity I approached it with a stiff upper lip. But it actually wasn’t too bad. I realized I was in exactly the same position I’d been in 3 years ago – having to stop often to catch my breath, I’d trained myself to climb more slowly so I didn’t have to stop as often. I covered the 3 miles to the park in 2 hours, which didn’t seem bad. And as usual, I was grateful for how much better maintained the trails are here than back at home. Fighting through monsoon overgrowth of shrubs and annuals has become a real chore this year, but there wasn’t nearly as much of it in these mountains.

Clouds were drifting back and forth over the crest, and the temperature was mild when I started out, but I was soon sweating through my clothes, and before I was even halfway up to the park, I was sweating so hard it was dripping constantly from my hatbrim, nose, and chin – another thing I’m getting really tired of.

Then, as I continued past the park and rounded the corner into the big upper canyon, I was hit by a blast of cold wind, and quickly became chilled. This cold wind chased me for the rest of the climb – my hat and shirt didn’t dry out until I reached the end – so it was only the effort of climbing that kept me from being miserably cold.

This second stretch of the hike is not quite as steep as the first half, and I was able to maintain a good pace until the last mile, when I really ran out of steam and had to stop often. It’s always been a hard slog – it originally took me 3 tries to reach the top. But today I was determined to go farther than ever before – to explore a little of the crest trail beyond the junction, into the other big canyon in the south of the range.

In the bleak, burned saddle at 9,300′, the trail disappears in overgrowth of annuals, and makes a sharp turn to traverse the next peak toward the actual crest trail. It’s only because I’ve hiked it before that I know where to go at this point – there’s an almost invisible path through the shoulder-high ferns that you can only detect when you’re right on top of it, and even then you have to use landmarks ahead and behind to keep on track.

But this traverse lies at the southwest head of the long, deep canyon, and today’s wind was out of the northeast, so the entire canyon was acting as a funnel, and all along this traverse I was subjected to gale-force wind, intensifying as I reached the junction saddle. I was only able to keep my hat on by cinching it down tightly over my ears.

It’s always great to reach a new watershed, with new vistas – this hike progresses across 3 major ones – but it was so damn windy I couldn’t linger. I only explored about 300 yards up the crest trail before it was time to turn back.

My shirt and hat were finally dry, but now the wind was in my face as I started back down the big canyon. It’d been a grueling hike and I was feeling a little sick at first, running out of breath and having to stop occasionally, but after the first mile of descent I was okay. The lower I climbed, the wind gradually slowed and temperature gradually increased, until when I reached the pine park I was actually warm again.l

From the pine park, you’re descending a north slope in late afternoon, so you’re mostly in shade, with long shadows from the crest cutting across the slopes ahead, making wonderful patterns of light and dark. As usual, I was looking forward to burrito and beer in the cafe, but still lingered as much as time allowed, to admire flowers and butterflies.

August 29, 2022

Fall of the Elders

Since mid-June, when this year’s massive wildfire burned through the habitat of one of my regular hikes, I’ve been yearning to go back there. But the Forest Service had issued a closure notice for that entire area effective until the end of the year.

The trail is really popular with Texans from El Paso, so on Saturday, on a whim, I checked the web page for that trail on the most popular online hiking forum, and found trip reports from a couple of weeks ago saying the trail had just been reopened. So this Sunday’s choice of a hike was a no-brainer!

I was especially concerned about the beautiful old-growth fir forest on the back side of the peak. That forest had survived the big 2013 wildfire as an island of lush alpine growth, and there were two ancient firs I really loved that stood on each side of the trail, like sentinals. During this year’s fire, the incident team had noted that the burn on top of the peak was low-intensity, so I was pretty sure my favorite trees had survived.

The weather forecast I quickly checked before leaving predicted cloudy skies and mild temperatures, so I reluctantly pulled on my heavy waterproof boots and packed the heavy, uncomfortable waterproof hunting pants. I was so tired of dressing for rain! But by the time I’d crossed town and entered open country, I noticed there wasn’t a single cloud in the sky ahead. Damn! Had I forgotten to refresh the weather page? It doesn’t auto-refresh on every platform – maybe I’d been looking at yesterday’s forecast.

The highway was virtually empty of other vehicles, but I came close to hitting deer twice – our deer population has exploded again, and driving anywhere outside of town is super stressful. But on the plus side, as I was slowly winding up through the tall forest toward the pass, a bobcat crossed in front of me. I hadn’t seen one in years.

Since this is our most popular trail with out-of-towners, I always expect to meet other hikers, and today was no exception – within the first 2 miles I encountered a single middle-aged man heading back out. We exchanged brief greetings but that was clearly all he was interested in. Most people using this trail are simply heading for the famous fire lookout on the peak, but I’m here for the wilderness – I bypass the lookout and continue several miles farther on the crest trail.

This year’s fire had stopped its southward advance at the peak, 5-1/2 miles north of the trailhead, and its scar couldn’t even be seen until you reached the top. But the 2013 wildfire had turned most of the crest into a treeless moonscape, colonized in the intervening years by shrubs and annuals. After this year’s wet monsoon, I saw plenty of flowers and birds in that area.

And during the initial traverse through the old burn scar, I was a little encouraged to see some small clouds rising behind the crest to the north. Maybe I’d get some weather after all, to justify my preparations!

By the time I reached the end of the burn scar at a saddle below the peak, a storm was definitely brewing in the north. And it hit me just as I crossed the southeastern shoulder of the peak, quickly developing into a heavy hailstorm as I scrambled to change pants and pull on my poncho.

Climbing the final switchbacks to the peak, I finally came upon scars of this year’s fire. Here, they were simply small black bare patches in a sea of lush annuals – it looked as if windblown sparks had started spot fires that had burned out without spreading.

But when I traversed around the peak through the lush forest below the lookout, I became confused. This area alternates between dense stands of fir and small grassy meadows surrounding isolated stands of venerable pine, fir, and Gambel oak. Here, many firs had been killed while their immediate neighbors had been spared. As before, there were small black bare spots where ground fires had burned with high intensity, but hadn’t seemed to have spread. The more I looked, the harder it was to tell where and how the fire had actually burned, because most of the ground cover was grass and forbs, which could’ve come up after the fire.

Suddenly I came upon two blackened stumps, and realized my favorite firs had not only been killed – they’d completely burned down. It was so strange – firs only 40 feet from them hadn’t even been scorched.

The peak forest is an island. Forest on the slopes below it was destroyed in the 2013 fire, and the trail there is crowded with seedlings of thorny locust and aspen. Some of this survived this year’s fire – enough to really slow me down.

And at the bottom, a trail junction and saddle where some tall ponderosas had survived the 2013 fire, this year’s fire had burned hot. The tree holding the trail signs had been torched – its charred trunk lay on the ground, and the trail signs had apparently burned to ashes. I’d often stopped at this saddle for a shaded lunch or a few minutes’ rest, but it was a bleak place now.

Beyond the saddle was a bowl that had been turned into a chaos of fallen logs by the 2013 fire, and these logs had clearly provided fuel for this year’s fire. Now that those logs had burned, along with the new growth of shrubs, this year’s wet monsoon was quickly eroding the bare soil and washing it downstream.

Below the bowl is a narrow canyon, whose forest had been partly killed by the older fire. This year’s fire had killed all the rest, and this summer’s rains were alternately flooding the creek with debris and cutting it into deep gorges.

The trail through this canyon had been cleared of logs just last fall – 8 years after the 2013 fire – and now it was rapidly being eroded away. As usual, it was only my past familiarity that enabled me to follow it. Slowed down by all the fire damage, I only made it to the second saddle – a mile short of my destination. The rain had finally stopped, and despite frequent thunder from surrounding storms, I could pack away the poncho for the rest of the hike.

The rain had chilled the air here between 8,000′ and 10,000′, so I could climb the 1,400′ back to the peak without much sweating, which was a relief from the heat and humidity of so many recent hikes. And as usual on crest hikes, there were no flies bothering me!

The long descent gave me an opportunity to watch storms developing far away across the landscape, as well as to appreciate flowers and fungi I’d missed on the way up. Just below the peak, I surprised a small hawk from the slope just above the trail. It first thought to perch on a seedling right in front of me, then decided it was too close and soared away to a much farther branch, so I couldn’t get a good picture.

The work of my hikes seldom ends when I reach the vehicle. During a wet monsoon, or in winter snow, my gear gets soaked and filthy. I can’t relax back home until it’s stashed somewhere for next morning’s cleanup, and the next day begins with a cleaning session for hat, boots, pants, poncho, etc.