Max Carmichael's Blog, page 12

June 2, 2023

Birthday Trip 2023: Day Four

Day three was my birthday, and I wanted to avoid driving, so I just relaxed in my room, writing about day two and trying to figure out what to do next. On the dozen or so previous visits I’d made to this region, I’d seen all the famous and easily-accessed petroglyph and pictograph sites. More remote “rock art” locations used to be shown on AAA maps, until it became obvious that the general public saw this as an invitation to vandalize.

Since then, people who care about these artifacts have generally avoided publishing their locations. In addition to climate change, the spread of invasive species, and the breakdown of local communities, vandalism is one of the many tragic consequences of our mechanically-enhanced mobility. Giving random strangers access to the locations of prehistoric sites truly is an invitation to vandalize in a society with such poor social controls as ours. And if you care about these things, you really should get to know and establish trust with the local people who know where they are, before even thinking about looking for them.

But for this trip I’d been able to round up a few online accounts of lesser-known sites, written not by enthusiasts but by ordinary off-road adventurers. I’d printed those at home, and now in my room I laid them out on the spare bed, along with the relevant maps.

Usually I schedule trips to avoid holiday traffic and crowds, but my birthday fell on Memorial Day weekend this year, and day four was pretty much the big day, the Sunday before the holiday when most travelers would be packing up and heading home. My Sunday destination was a big canyon south of town which I’d somehow never noticed before, and which one of the adventurers said had “a lot of rock art”. A high-clearance 4wd track winds down it for about twenty miles from the highway to a river crossing, past which the track continues eastward. I had no hope of fording the river, but hoped to find a campsite and spend the night. I had no idea what the conditions would be like or how far my vehicle would get on what would likely be a difficult road.

After turning onto the back road, the first thing I found, even before the track entered the canyon itself, was a monster pickup truck and a huge travel trailer, detached, parked in a stark roadside clearing. I assumed the owners were out exploring in their UTV. I’ve always had trouble finding campsites in this region because most clearings are designed as parking areas for RVs, right beside the road, since people who travel with their own self-enclosed homes have less need for isolation.

I rattled and bounced across a rolling plateau for about three miles until the road finally wound down into the canyon proper, where I found a place to pull over. The author of the online report hadn’t given site locations so I wanted to check upstream on foot before driving ahead.

I walked nearly a half mile upcanyon but saw nothing promising. This is BLM land, open range, and I found occasional old cowpies throughout the day, but nothing recent.

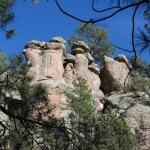

The canyon was already awe-inspiring, and it became more so the farther I went. Suddenly I rounded a bend and saw a spread of brilliant green ahead – a stand of cottonwoods. I came to a sidetrack that led up a sandy bank into a small grove, and behind it was a cliff that looked promising.

Rock writers in sandstone country typically made use of sheer cliffs that were darkly patinated and free of drainage from above. When you’re looking for sites, you look for smooth, shiny cliffs that are free of water streaking and are reachable by human hands. Sometimes they’re elevated dozens of feet above the canyon bottom, requiring field glasses to spot, followed by a steep climb up a boulder-strewn debris slope.

I drove up onto the sand bank, and soon saw the petroglyphs. It was a nice site, but sadly vandalized with prominent graffiti – names and initials are the typical product of Anglos with limited imaginations and boundless egos. There was a perfect campsite here, so I memorized the location in case I didn’t find a better one downstream.

I soon came to running water, and a pool full of tadpoles. I pulled over for a young couple driving up canyon in a small side-by-side UTV – obviously the owners of the big truck and huge trailer I’d passed near the highway. Their monthly payments for all these toys could exceed my Social Security income!

Past sweeping bends beneath towering cliffs, I was driving slowly and craning my neck from side to side, glassing for likely sites, and I finally spotted a second site, about fifty feet up a debris slope. It was on a series of barely patinated, eroded, and stained rock faces – not the best surfaces for preservation – but because it required a climb, it had escaped vandalism by lazy white folks.

Downstream, I found more water and more lush vegetation, driving through a shallow pool then encountering a muddy one about forty feet long whose depth I couldn’t determine, so I stopped. I heard an engine approaching from behind, so I backed up, and the young couple whizzed past again on their UTV, splashing through the big pool, which reached their floorboard. Too deep for me!

It was lunchtime, but the canyon was narrow here, and I had to roll a heavy boulder out of the way to make a parking space off the roadway. Then I heard an engine approaching from downstream, and climbed up the bank to watch them drive through the big pool. It was a lifted pickup with big tires, and the water reached the axles – well over a foot deep.

I was making a sandwich out of the back of my vehicle when the young people passed a third time. They laughed and said they’d dropped a phone down-canyon and had to return to get it. One of the hazards of riding in an open vehicle. I congratulated them on finding it. Definitely not a day for solitude in a remote canyon.

Just as I was preparing to carry my lunch up to the shade of a cliff, another vehicle approached from up canyon – one of these rare super-UTVs with a lifted suspension, fully exposed frame, widened track, and giant tires like something out of Mad Max. It was a friendly couple, probably in their early sixties, who had no idea where they were or where they were going, and asked if I had a map. Of course I was loaded with maps, including detailed topo printouts for this canyon, all of which the woman photographed with her phone.

Their RV was parked just off the highway at the foot of the high mountains, about twenty miles south. They were from Grand Junction, Colorado, “thirty minutes from the Utah desert”. They used to haul their boat to Lake Powell south of here, but were now more into backcountry exploring, and like almost everyone who visits these areas now, they base themselves in their RV and explore by UTV. Their goal was just to drive as far as possible all day on back roads, avoiding the highway, returning to “camp” by different routes if possible, so my maps were a great help. I warned them there was a river crossing at the mouth of this canyon, and the river was likely in flood.

After lunch, I had to climb and follow a ledge for several hundred yards to get past the deep pool. Back down on the rocky road, it was a hot day to be walking exposed under the sun, with cliff swallows swooping and crying overhead, the cliffs and rock outcrops approaching and receding over and over, as I rounded the never-ending sweeping bends, glassing for petroglyph panels above.

I climbed through a grove of cottonwoods and partway up a debris slope without finding anything, when I heard more engines coming up canyon. They passed below me, oblivious, a convoy of nine vehicles led by what looked like a boxy, repurposed game warden truck, followed by various Jeep Wranglers, Toyota FJs, and lifted pickups, and ending with a stock Toyota Highlander, which I was amazed could ford the deep pool. Then I descended and continued down canyon until I spotted the next site.

This one required a more precarious climb, but had been attacked anyway by enterprising white vandals. Nor was it as interesting as the earlier panels.

I continued downstream, but the canyon became wider and the cliffs taller, with debris skirts over a hundred and fifty feet high. I glassed promising, darkly patinated rock faces but could find nothing up there, I had no shade and it was getting hot, and I kept having to climb out of the track to let off-road vehicles pass, so I finally gave up. On the bright side, I’d encountered very few flies, despite the warmth, old cattle sign, and abundance of water. That original shaded campsite was beckoning – hopefully no one else had taken it yet.

As I walked back, I pondered my goal for these trips. Looking for more obscure prehistoric sites, I’m destined to reach a point where my vehicle can’t proceed and I need to walk miles on sun-exposed canyon roads, passed by UTVs and lifted pickups full of oblivious explorers. Is this really how I want to spend my time in nature?

Even if I had a more capable vehicle, that would just mean more driving time and less hiking time. Maybe I should be looking for better hikes, closer to the highway, instead of better prehistoric sites, and give up on the really remote stuff requiring long backcountry drives.

I reached my parked vehicle just ahead of the couple from Grand Junction. They’d crossed the flooded river – it reached the floorboard of their side-by-side, which was waist-high for me – exploring for an hour or so toward the Maze district of Canyonlands. I said I’d been looking for rock art, and they were surprised, as if they’d never considered any purpose for being here other than driving. So I tried to describe how to find the site I was hoping to camp at.

They were admiring the petroglyphs and bemoaning the vandalism when I arrived. “Why do people destroy things they don’t understand?” the woman cried. “Big question,” I answered, and the man grinned sadly, shaking his head. I actually think it’s complicated, with almost as many answers as there are vandals. In the old days, ranchers and cowboys likely saw the Indians as barbarians and prehistoric artifacts as the work of Godless heathens. Today’s young people have been abused by a dysfunctional society and are as likely to destroy as to create. I’d chanced upon a professional rock art website the day before and learned one of the most spectacular and well-known panels on the San Rafael Swell, north of here, had recently been defaced, so although most of the vandalism I’d seen today was historic, the problem is just as bad now, after generations of what we call “education”.

We talked pleasantly for a while, comparing our hometowns and favorite haunts – they said they lived in paradise but loved the desert too, and were hungry for information about this area. They said they’d been snowed on in the mountains last night, while I was sleeping my motel room below, in town. They said they had to drive home tomorrow, and I mentioned I was retired. They said that was hopefully only a few years away for them, but with all their investment in toys, I wondered how soon they’d really be financially secure. A rig like theirs – truck, trailer, and super-UTV – could cost well over $200,000, and when combined with a home mortgage, the monthly payments could postpone retirement indefinitely. They do save the cost of motel rooms, which for me can amount to $1,500 a year. But I’m guessing for many people I encountered that day, expensive toys would become a burden.

The sun was still high, so I filled my shower bag and left it on a rock to warm up while enjoying an early beer. Then I noticed a couple of cottonwoods separated by the perfect distance for my hammock – I’d had to replace my original Yucatan hammock after the house fire, and this would be the first test of the replacement.

That shower was wonderful and it felt great to be clean again and wearing clean clothes. Vehicles kept passing but I was screened by cottonwoods. I lit my oil lantern and made dinner after sunset, had an unusual second beer, and sat out under the light of the high half moon, admiring it and Venus, which was setting in the west. I had bad double vision, but it varied from minute to minute and I could sometimes reduce it by concentrating. In a tiny vehicle I’d paid $4,000 cash for, I’d carried everything I needed to be safe and comfortable outdoors. I would sleep out under the stars, the way I was taught.

I can enjoy nature in the daytime without leaving my home. But when I go camping, I want to recapture the experience of my ancestors, to adapt to and learn from new natural habitats both day and night. I spent much of my life learning the skills required to live simply outdoors, and I’m still learning – why would I want to give up that priceless achievement now? Why would anyone need to haul a familiar kitchen, bath, and bedroom with to them into the backcountry? It reminds me of the big box chain, Camping World, that specializes in RVs, trailers, and accessories. That’s not camping to me.

Finally I went to bed, and tossed and turned in the hammock for several hours. It’d been a few years since I’d slept in one, my back condition had been getting worse, and I’d settled into a habit of sleeping on my stomach, which isn’t possible in a hammock. It was 11:30 when bright lights suddenly hit the crowns of the trees above me. The light bounced around, then I heard a dog barking. I looked over at the sandy trail that led to my campsite, and saw a truck approaching slowly, a middle-aged woman walking beside it, and a big dog running toward me, barking. I yelled that the site was occupied, but the dog ran right up to my hammock, jumping and barking violently. I yelled to the woman, and she ran up to me and grabbed the dog. Without apologizing, she returned to the truck and with difficulty, they backed out.

I swore to bring “Occupied” signs to post at the access points on future trips. Giving up on the hammock experiment, I used a flashlight to find a level spot, unpacked my tarp, sleeping pad, sleeping bag, and pillow, and finally got to sleep well after midnight.

May 27, 2023

Birthday Trip 2023: Day Two

My next destination was a motel in a town four hours west. On the way, I would attempt a side trip into some forbidding back country, hoping to explore a remote canyon where others had found rock writings and paintings.

I headed west on what may be the world’s most beautiful highway, frustrated that I couldn’t stay in this area for months instead of days. In the past, I’d dreamed of exploring the sprawling, red sandstone plateau that loomed 1,600 feet above on my right. But it features forested habitat similar to our high mountains back home, and my vague goal for this trip was to find unfamiliar pictographs, not familiar habitat. So I kept driving past one of my favorite landscapes and reminiscing about past visits.

Past the alpine plateau, the road enters a land of red-and-white sandstone, following ledges between high mesas on your left and deep, sheer-walled canyons that are mostly hidden at right. It gets drier and more stark as you approach the River, and finally the peaks of one of my favorite mountain ranges emerge from behind the mesas to the west. They were still carrying a lot of snow, and while I was getting sick of snow at home a few months ago, I always thrill to see snowy mountains in the midst of desert at this hot time of year.

The River crossing is a truly awesome, heart-in-throat place which is normally passed too quickly on the highway. But my turnoff was just past the bridge on the right – an unmarked dirt road.

This is one of the few routes into the most inaccessible parts of the canyonlands – the terrain in which Jeep commercials are filmed. I’ve driven shorter, less rugged roads on similar terrain in nearby areas, but I expected this road to be the harshest test of my vehicle ever, and I wasn’t disappointed. Driving here comes with all kinds of warnings – if it rains, you’ll be stuck in cement-like clay, and if you break down and need a tow, it will cost a minimum of $1,500. Of course there’s no chance of cell phone service anywhere nearby.

I pulled over just past the turnoff to review my maps. And just as I finished, a convoy passed me: a late-model 4-door Jeep Wrangler and a Toyota FJ, both kitted out in full expedition gear. I pulled in behind them, and to my surprise and probably theirs, it soon became obvious I was faster than them. They stopped to take pictures, pulling over so I could pass.

This was completely new country for me. I discovered that the road follows ledges around the base of mesas, with a maze of canyons below on your right. My destination was only about nine miles away as the crow flies, but it takes over twenty miles of driving to get there because the road repeatedly winds back into deep coves then leads out around sharp points, following the ledges to skirt the network of canyons below.

Soil is very thin in this country, and like most, this road was built on bedrock, so I soon encountered what I’d expected: stretches of rumpled sandstone that you have to cross very slowly, rocking back and forth, if you can – there are always transverse ledges and spines that require high clearance. And then, when the road crosses a wash that forms the head of one of the lower canyons, there are sections blocked by boulders and ledges you have to carefully drive over so as not to break an axle, or a differential, or get stuck with a wheel in the air.

I was amazed at how well my little Sidekick did, especially considering its competition. I hadn’t even needed my 4wd yet, and I got farther and farther ahead of the Jeep and Toyota, but it still seemed to take forever. Each point I rounded revealed a whole new landscape.

Despite the dozens of very slow bedrock sections and boulder-lined washes, I was pushing my little vehicle everywhere else, averaging at least 15 mph. Finally I crested a rise and saw what I believed to be my canyon down in the bottom of a broad valley. Again I stopped to review the maps, and before I could get going again, the Jeep and Toyota overtook me for the second time, all waving and smiling.

But when I reached the bottom of the valley, I ended up passing the Toyota yet again – while all I was using were paper maps, the driver was checking GPS on his phone. Here, the road forked – I was taking the dead-end left fork up the canyon, thinking I would eventually encounter the Jeep, but I eventually learned that the others had taken the right fork farther into the backcountry.

I was here because an online trip report by “rock art nuts” said they’d found both petroglyphs and pictographs up the canyon. The road just followed the dry wash, which, since there had been rains a while back, was now hard-packed red clay. The surrounding valley started out open, but after a mile the cliffs closed in on both sides and I came to an old corral – the only human structures in this region are corrals. Beyond that point the wash was only wide enough for my vehicle, and I soon came to bouldery stretches that required all my ground clearance and concentration. Too late, I realized I should’ve parked at the corral and walked in, but fortunately I soon came to a campsite where I pulled up and parked. Time for lunch! And someone had long ago left a much-corroded chrome dinette standing here among the junipers, which I hauled into the shade.

Despite the spectacular surroundings, the long, strenuous, rough ride had left me in a strange mental and emotional state. I found I was suddenly severely absent-minded, with virtually no short-term memory. Powerful gusts blew down the canyon, knocking things over and sending me chasing after them.

After lunch, I packed for a hike up-canyon, but I kept locking the vehicle only to have to unlock it and unpack it again to find something I’d forgotten. I couldn’t get anything right the first time.

As soon as I started walking I discovered I was the first person to drive up here in a long time. The only remains of tracks were from a UTV.

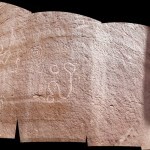

The road, such as it was, veered out of the main canyon into a side canyon, and the main canyon became impassable to vehicles. And past that point I found a simple petroglyph panel.

To my chagrin those were the only prehistoric markings I found in that canyon.

I returned and followed the road into the side canyon. All I found there was an old print of a cowboy boot, and some ranching debris.

So I returned to the Sidekick and drove back to the corral, where I saw another side canyon, and found an old road leading to a campsite in its mouth. I explored that canyon on a cattle trail, and found it was a box canyon, headed by cliffs with a dry pour-off high above, and with an old earthen dam below which had been breached by flood. As I approached, a great horned owl flew out of a juniper in front of me. It went left out of sight behind vegetation. And then as I proceeded toward the cliffs, I thought I saw something flying to a crack up there, so I snapped a quick picture. In my room that night, I zoomed in on the pic and sure enough, there was the owl, huddling under a small bush.

Like I said, I was in a weird state. I felt really disappointed at finding only one little petroglyph panel after such an arduous drive. I was perfectly aware I should be thrilled by the natural beauty surrounding me, as I would’ve been in the past, but I simply wasn’t, and I couldn’t figure out why. Maybe it was some kind of physical depression.

On the drive back to the highway I took it slow, stopping frequently for water and pics. My clutch is wearing out so that it needs annual adjustment, and it was becoming almost impossible to shift gears without stopping and turning off the engine first. That’s something I can fix and will probably have to in the next few days.

The day had felt either hot or cool when I was out of the vehicle, depending on whether I had shade from cliffs or clouds. But in the vehicle it was always hot – big windows all around – and I soon turned the A/C on high. The highway drive up the long wash from the river went smoothly, and went even faster once I emerged onto the rolling country below the snowy mountains.

When returning on the back road along those ledges I’d been hearing a strange squeaking noise from the back, and about ten miles from town I suddenly remembered that when I stopped in that canyon for lunch, I’d taken two bundles of firewood out of the vehicle so I could reach my clothes bag underneath, and set them loosely on top, so they hung out over the edge of the roof rack and would be easy to notice so I wouldn’t forget to put them back in afterward.

But in my absent-minded state I’d forgotten them completely, and in all the bouncing and shaking and rocking over twenty miles of that bad road they’d certainly bounced off, probably before I even left the canyon. And even if they’d survived that, driving 65 mph on the highway would’ve definitely blown them off.

But I watched for several more miles until I saw a turnoff. And once stopped, I found that the firewood bundles had settled into the space between crossbars of the roof rack, miraculously surviving all that rough ride and highway speed. Something good was finally happening!

As I drove north to town, I passed a continuous parade of big southbound pickup trucks hauling powerboats that were twice their size, heading south to Lake Powell. It was Friday evening, and dozens and dozens of Mormon families from the tiny hamlets of the remote interior were driving hours to spend their national holiday on the doomed reservoir.

Birthday Trip 2023: Day One

After making a solitary trip to my desert land last fall, I told everyone I would return for a more social visit in the spring. But over the winter I became immersed in finishing my book project, and as it got better and closer to being finished, the desert trip got pushed back.

The book was essentially completed a couple of days ago – I ordered a one-off print copy for my mom, who will be my first reader – so I was finally free to travel, just in time for my birthday.

On the planned day of departure – to my amazement – I was fully packed with a full gas tank, and left precisely on time, at a reasonable hour in the morning but with plenty of time to reach my first day’s destination long before sunset. For some reason, for the first time in my life, I was starting a trip not frantic and beside myself with stress, but fully prepared, having checked and double-checked my packing list. For perhaps the first time in my life, I was starting a trip in a state of perfect calm.

My little Sidekick was packed with everything I would need for a ten-day backcountry trip, yet it looked nothing like the humongous “overlanding” rigs every yuppie is now expected to have for expeditions like this. One reason I chose and keep this vehicle is that you don’t have to climb up or bend over to reach any of the cargo, and the rear passenger doors provide easy access to stuff packed in the middle. There was even plenty of headroom left to see out the back.

My usual starting point for this trip is a small town in southeast Utah. But it’s seven and a half hours from home, and years ago I vowed never to drive more than six hours in a day. In the past, I’ve started later and made an intermediate overnight stop. With a stop to make lunch, today’s drive would last more than eight hours, and by the time I reached the north end of the Navajo Reservation my calm was gone, I was thoroughly frazzled, and both my hip and shoulder were in pain. I did arrive long before sunset, but I still had to shop for supplies before dinner and a shower.

I’d booked a room in the motel Katie and I had discovered on our “rock art expedition” in April 1987. Designed by a student of Frank Lloyd Wright, it’s a small, modest structure that nevertheless won our admiration with its clever adaptation to its high-elevation Southwestern habitat.

I’d stayed there once since, a few months before COVID, and found it in harsh decline. The original clerestory windows that you opened with a long-handled crank had been replaced by fixed windows, the beautiful built-in hardwood furnishings hadn’t been maintained, and the place had been clumsily rewired so that my neighbor woke me up in the night because his TV was plugged in to my room through a ragged hole punched in the wall between us.

After COVID, two local women bought and refurbished the place. Now, it’s modern and fairly comfortable, but it’s lost much of the old “Wright” feel.

May 22, 2023

Wilderness Access, but at What Price?

Again I had trouble choosing a Sunday hike – my first choice, on the east side, turned out to still be inaccessible due to road closure. Then I drove west planning to try an alternate route to another trail that had been inaccessible since last fall, but at the last minute decided that was too risky, too. So I continued to the turnoff for a trail that had been wiped out last September by a big flood, because I’d seen some notes online that indicated someone had been using it recently – maybe they’d cleared a path through the damage.

This is one of those few trails leading to the crest of the range that are precious to me. So imagine my delight when I found that someone had cleared a path and laid down good tread through last year’s flood damage!

It had rained yesterday, the temperature was in the low 70s, and as soon as I reached the canyon bottom a rich cocktail of plant perfumes hit my nostrils. Spring flowers were out, and my boots and pants were soon soaked with dew.

But after I reached the abandoned cabin, the trail work ended. Distances on this trail are confounding. The cabin doesn’t show up on any maps – I’ve always assumed it’s two miles in from the trailhead. I’ve hiked this trail often enough that I was easily able to find my route through flood debris, blowdown, and overgrowth beyond the cabin, but two things soon became obvious: big floods like this renew habitat, and the equestrian trail crew had been here, because the trail was now lined with invasive dandelions.

Despite the online notes, and invasives spread by horses, I found no tracks anywhere. It looked like I was on virgin trail, especially as I began climbing the traverse to the first saddle. Birdsong surrounded me everywhere, and the traverse was more choked than ever by scrub oak, manzanita, and the thorny shrub I have yet to identify. I literally had to force my way through dense thickets in addition to climbing over occasional blowdown, all the way up to the saddle. Most hikers would’ve simply turned back, assuming the trail no longer exists, but I’ve gotten used to conditions like this and can follow even the most subtle indicators of a route.

Storm clouds had started peeking over the crest even before I left the canyon bottom, and now towered over the ridge to the east.

It took me over three hours from the trailhead to reach the saddle, which is shown on maps as a distance of less than four miles. This never fails to amaze me, because I’m good at estimating distances, and this part of the trail always feels closer to six miles. And I hadn’t been moving slow – the trail in the canyon had felt easier than usual to follow.

Past the saddle, the trail climbs steeply in a series of switchbacks, which are not shown on any maps. A hiker who had left a recent note online said the trail simply stops here, but of course I know the route well and had no problem continuing. But the shrubby overgrowth was so bad on this next ascent that I fell once, tripping over a low branch that had been hidden by the plants I was pushing through.

Beyond the switchback, there’s a traverse that rounds the base of a white comglomerate cliff and enters the head of the main drainage, revealing the arc formed above by the crest. As before, there were no human tracks anywhere, but elk love this area and are the only thing maintaining tread at this point. I suddenly realized that I so seldom find footprints on these wilderness trails because backpackers are the only people who penetrate as deeply as I do, and backpackers in this part of the range are few and far between.

The trail traverses toward a second set of switchbacks that lead to a second saddle. But these switchbacks are faint and easily confused with numerous game trails left by elk, so I usually end up finding different routes going up vs. coming back down. At the saddle, the little cairn I’d made a couple of years ago was still waiting for me.

Past the second saddle, there are only faint, occasional traces of a trail, but again, I know the route well. After entering intact forest, it climbs in several switchbacks – also omitted from the maps – and passes an old junction before beginning another long traverse toward the crest.

This traverse looks exactly like a game trail. If you can follow it, it leads across a series of narrow talus falls, through thickets of thorny locust, to more switchbacks that climb the back side of a sharp rock outcrop. The air was muggy and I’d been getting pretty hot climbing thousands of feet, but as I continued up this traverse the clouds had been spreading, it had been getting darker, and a cold wind had dropped the temperature to the 50s.

Stopping before a switchback that’s blocked by deadfall, I noticed a tick on my sleeve, and after brushing that one off, saw one climbing my pant leg.

It’d been a hard climb and I was really beat. And my time was running short, so I stopped at the top of the switchbacks, next to the upper part of the rock outcrop, instead of continuing a couple hundred feet higher to the ghost grove of burned aspens below the crestline, as before. I figured I’d gone almost seven miles and climbed 4,000′, although the map would show less than six miles and 3,600 feet.

On the way down, the leg cramps began, and continued for the next three miles. I always get leg cramps on this descent, and this is the only hike where I get them – despite other hikes being much longer and harder. I drink plenty of water, with added electrolytes, and stretch regularly, but it makes no difference. Something about this hike just triggers cramps.

I’d only felt one tiny raindrop, and now the clouds were moving off and the air was quickly warming. When I reached the first saddle, I stopped to do a complete series of lower-body stretches, and drank a bunch more water.

Despite all the precautions, I still fought cramps all the way to the canyon bottom. And when I reached the bottom and began seeing dandelions again, I slipped and fell a second time, at a debris-choked creek crossing, and thought more about trails, condition and maintenance, and the larger issue of wilderness access.

Although I usually give up when confronted with hundreds of fallen logs per mile, I figured I’d climbed over at least a hundred today, spread out over a distance of six or seven miles. And I’ve long been perfectly content with trails that are faint or overgrown by thickets. But the vast majority of hikers seem to expect trails that are clear and meticulously maintained – probably because most of their hiking occurs in crowded urban parks and popular national parks, where the effort and cost of trail maintenance is justified by the level of traffic.

I only recently had the revelation that trails themselves, as we know them, are a product of wildfire suppression. The trail networks in our national forests and parks would never have been sustainable before, in natural wildfire regimes, which regularly rearrange the landscape.

But very few hikers, even backpackers, will attempt to penetrate wilderness areas without trails. So the whole idea of “wilderness access” ultimately depends, to some degree, on wildfire suppression.

And the demand for wilderness access has led, since COVID, to some troubling trends in my region. Just over the border in Arizona, a coalition of urban mountain bikers has been granted a permit by the Forest Service to do all trail maintenance, and the mountain bikers have accompanied their work by a slick online propaganda campaign, in which they conceal or downplay their agenda as bikers, promoting their selfless work “for the benefit of all trail users”.

Equestrians are doing the same thing in my local forest. They got an exclusive permit to do trail work, and they’ve established a slick, authoritative website on trail conditions which likewise hides their agenda as equestrians, claiming to be selflessly improving trails “for the benefit of all trail users”.

It’s clear to me that both these special-interest groups are working proactively and effectively to assure themselves access to public lands. Equestrians know they’re accused of damaging trails and spreading invasive plants, and afraid of losing access, they’re positioning themselves so nobody can exclude them from wilderness.

Likewise, mountain bikers have been fighting for decades to get access to wilderness, and by making themselves indispensable to all trail users, they may finally succeed.

My question is, does anybody actually deserve good trails, and “access to wilderness”, at the cost of habitat degradation?

May 8, 2023

Trail Fraud!

Today I got to do the hike I planned last Sunday – 18 miles on good trail to rebuild my capacity. Only 20 minutes from town so I can get an earlier start and have more time to hike.

The first stretch is two miles on a primitive road, crossing and re-crossing a perennial creek below rock cliffs and pinnacles. I usually run into others in the first mile, and today was no exception – I met two birders from New England a quarter mile in. They’d already seen new warblers and were really excited. I encouraged them to continue to the narrows, the most spectacular part of an otherwise fairly boring hike.

I was a little surprised to find the road through the narrows recently rebuilt after last fall’s severe flood damage. It must’ve cost the private landowners an arm and a leg, and of course it’s likely to happen again every few years. The property up the road was recently sold, presumably to outsiders who had no idea what they were getting into – like the birders who built and had to abandon the cabin I found over in Arizona.

As usual, I made good time on the six-mile climb out of the canyon to the 9,035′ peak, where the trail is mostly shaded by forest and I was kept cool by a breeze. It really is nice to have a good trail for a change after slogging through deep snow or fighting my way through flood debris and thorny overgrowth for months.

On the way down the north side of the peak I ran into a friendly couple about my age, from a rural community west of town. They were trying to reach the iconic twin peaks north of town, but had missed the turnoff I used and had continued another 5 miles on the highway to the dirt forest road that accesses the fire lookout, driving that an additional 5 miles all the way up to a nearby saddle at 8,600′ instead. Now they were hoping to descend this trail in reverse from the high peak, to reach the much lower twin peaks. They asked about my hike and were pretty shocked by the distance I was aiming for. I gave them all the helpful info I could think of, but was perplexed because there’s no actual trail up the twin peaks, and I’ve never thought of them as a destination.

My destination was the “park” – the level basin at the far end of the eastward ridge, where the national trail crosses and drops to lower ridges. I love these incongruous geological features with their ring of tall pines surrounding a grassy meadow in the center, high in the sky on top of a ridge, and assuming I could make it that far today, I planned to collapse on the ground in the shade of a pine and rest a while.

But first, a half mile after passing the couple, I met a guy in his 40s or early 50s with a dog, running a chain saw, cutting logs that had recently blown down on the national trail. He refused my offer of help so I thanked him and continued another couple of miles on the gentle grades of this section, to the park, where I was still feeling good, but stopped to lie in the shade for at least 20 minutes.

This is one of the two longest hikes I do, and the longest I’ve done in over six months, by a margin of four miles. I expected to develop some pain on the way back, and sure enough, both feet got sore before I reached the lookout road. And I encountered the log-cutter and his dog again. He was finishing up for the day so he was glad to stop and talk a while. Turns out he’s a mountain biker and fisherman, and clears trails so he can ride them himself or use them to access fishing holes. Of course he resents not being able to use his chain saw in wilderness areas, which have the most attractive fishing holes and are now out of reach because of flood damage and blowdown.

The most interesting thing I learned from him is that this section of the national trail isn’t used by through hikers. He laughed when I mentioned other sections I’d found abandoned or blocked by flood damage. “All the through hikers just go straight north from town on other forest trails, to the river, and from there to Snow Lake (50 miles west of the official national trail),” he said. “Nobody but me uses the national trail anymore – they all want to be next to water.”

This confirms what I’ve long suspected. So many times, I’ve seen through hikers tramping along highways, short-cutting much longer sections of trail through backcountry, so they can save time or reach town quicker to resupply. We just had our big “Trail Days” celebration a few weeks ago, but that’s mostly about business – through hikers spend a lot in local restaurants, motels, and stores. I doubt anybody admitted they weren’t actually using the highly publicized, internationally-known trail.

After climbing to the high peak and crossing the saddle to the south slope for my final descent, I ran into the couple from the western community again, on their way back to their vehicle. This time we really got to know each other and exchanged names. She was admiring my old Swiss Army surplus pack, and he was curious about how much water I take on these marathon hikes. This was really turning into a social day, and I was glad I’d met friendly people who were willing to talk.

I was walking so gingerly on the descent I had to take a pain pill, but in general, I was surprised not to feel more exhausted during the last couple of miles along the canyon road. I only do this non-wilderness hike when I feel the need to pile on the miles, but most people find parts of it both beautiful and memorable.

May 1, 2023

Missouri Attacks!

Still trying to rebuild my strength and lung capacity after a frustrating winter, I planned to do a nearby hike on a trail I knew would be in good condition. But I’d seen road cyclists all over the area, and a last-minute check showed that the road I needed would be closed for our annual cycling race. So I fell back on my old favorite trail, an hour away on the west side of the mountains.

There was a brand-new city SUV, a Toyota Highlander, parked at the trailhead, and the trail log turned out to be unusually entertaining. On April 17, a party of two from Missouri had taken up four rows with an extended rant using a red pen that they’d obviously brought for situations just like this. According to the Missourians, the wilderness map shows a good trail here, but the trail is actually “very dangerous for backpackers” and “constantly giving out when you walk on it”. They reached the second creek, where another trail branches off, but found “the trail does NOT exist anymore for the past 50 years” and therefore they “tore off the sign”. Adding insult to their perceived injury, they found no Rainbows or Gila Trout in the creeks, and they admonished the Forest Service to “get out the trucks and start cutting some trails!!!”

The next log entry, a week later, simply said “Trail is great! Grow a pair of ovaries” with an arrow to the previous comment.

Shaking my head, I started down the trail into the first canyon. The Missouri rant was so over the top, I figured there was a good chance it was a prank. I’d made a prank entry myself last year after someone else had criticized the trail condition. This is a trail of contrasts – unlike most other trails in our wilderness, it’s been easy to follow and clear of overgrowth, deadfall, and blowdown throughout the three years I’ve been hiking it. But its route involves very steep ascents and descents that make it inherently the most challenging hike I do.

I knew it was going to be a hot day – record heat was forecast throughout the Southwest, with temps in the mid 80s in town. I already had my shirt unbuttoned before I reached the canyon bottom, where I expected the creek to be in flood – hence I’d worn my waterproof boots. I strapped on my gaiters just to be safe, but keeping my balance with a couple of handy sticks, I was able to use stepping stones without slipping or submerging my boots more than about two inches.

The trailhead log showed 18 visits in six months, and most of those were day hikes which typically end after only a mile, here at the first creek crossing. Even the backpackers often get no farther than the campsite less than a half mile upstream. But I was here for the full workout, as much as 17 miles out and back.

The flies started bugging me as soon as I began climbing the switchbacks and started to sweat, so on went the head net, which I kept lowering and raising as needed for the rest of the day.

Up on the rolling plateau between the first and second creeks, there’s enough loose dirt to read tracks. Equestrians had been up here months ago, but there was only one recent human track – some kind of sneaker. And at the west end of the plateau a dog – a big shepherd mix – appeared, barking, followed by a trail runner, a big girl who looked like a college student. She raced past me as I asked how far she’d gone – “to the West Fork!”. She was the Toyota driver, and I wondered if was her parents’ car – it would be a spoiled college student who owned a fancy new vehicle like that. Most surprisingly , I didn’t notice her carrying any kind of gear – she might’ve had a small water bottle in her hand, or not. I spent the rest of the hike marveling at someone who would run more than 11 miles on a trail with over 3,000′ of elevation gain, on one of the hottest days of the year, with no more than a liter of water – if any!

I was even more perplexed when I started down the rock-lined switchbacks into the canyon. I did three months of trail running in our Mojave Desert mountains back in 2002, when I was in peak condition, and I recall only being able to run up about 300′ of elevation gain on good trail before slowing to a fast walk. And when I reached steep, rocky sections I was definitely walking. This trail has two sections of switchbacks, each dropping/climbing 1,400′, with sharp, loose rocks underfoot for much of the way.

I simply didn’t think it would be possible for anyone to run either up or down those sections. It would be like running in a road with a dump truck ahead of you pouring a layer of bricks in your path. Crazy.

I reached the beautiful floodplain of the second creek and discovered the Missourians were not pranking after all – they’d not only torn off the old trail sign, they’d either stolen it or hidden it somewhere. This was even worse than expected. What kind of hiker destroys a trail sign?

I’d already known their excuse – “the trail does NOT exist anymore for the past 50 years” – was false, because I’d hiked that trail several times in the recent past, for over a mile upstream, to a beautiful swimming hole. I began to think hikers – and especially backpackers – should have to pass a test in order to qualify for using our trails. Apparently what’s happening is that in our age of social media and parents who assume schools will raise their kids for them, naive, ignorant, and poorly socialized young people have unlimited free access to unreliable information online, and conceive wilderness trips they’re completely unprepared for. And when the reality doesn’t match their preconceptions, they take it personally and lash out.

In this case, the result was sad, because those historic trail signs are not easily replaced. And I hold outfitters like REI partially accountable, because their products and photo spreads set false expectations for conditions in the burn scars that now cover much of our public lands.

Despite being in the midst of a heat wave, I decided to bypass the swimming hole and continue across the second creek, over a shoulder toward the third creek more than a mile and a half away, because that would yield a much better workout. The third creek is a little too far for a day hike, but I did get as far as I’ve ever gone before, to the edge of a cliff a couple hundred feet above the third creek. And I paid for it on my return.

I found no tracks other than wildlife on this stretch of trail – I’m the first hiker here in the past six months.

It was the last day of April, but it felt like mid-June. After turning back, I could tell that despite bringing four liters, my drinking water was running low. But there were two creek crossings on my return where I could refill if needed.

Starting up the switchbacks, I began to feel the strain on my body, and thought about that girl again. I was having to stop about every 50 feet to catch my breath, and my whole lower body was on fire. I figured she must’ve known in advance that this is one of our few trails that are clear of overgrowth and blowdown in our current fire/climate regime – how could you run in shorts through thorn thickets and fallen trees? But in general – what kind of human would run up and down a steep trail like this, on loose, sharp rocks, with little or no water? It still boggles my mind.

The climb took me over an hour, and I finally swallowed a pain pill while crossing the rolling plateau.

I ran out of drinking water on the descent into the first canyon, but I decided not to refill at the creek – the final ascent to the trailhead is only another mile in the shade.

The pill kicked in and I felt much better climbing out of the first canyon – although it still feels like it will never end. At 14 miles and 4,400 feet of elevation, this was the longest hike and biggest climb I’d done in the past six months! Hopefully it’s another step forward in the recovery of my lost capacity.

PS: Directly above the Missouri rant on the trail log, there was an entry from a party of four, an “RAF/NMPA Work Party” claiming to have spent 3 days on the trail. I found this curious since this party claimed to have been working on the trail at the same time as the Missourians’ bad experience, so I looked it up when I got home. Turns out RAF is the Recreational Aviation Foundation and NMPA is the New Mexico Pilots Association. These guys weren’t using or working on the trail – they were installing a porta-potty at a dirt airstrip which has recently been refurbished nearby. Since there’s no rural community near this remote location, the only reason for an airstrip is so airplane hobbyists can fly in and out, adding it to their life list.

And of course, the past history of this airstrip apparently includes plenty of use by drug smugglers from Mexico….

The No Good, Very Bad, Absolutely Worst Trail Ever

Still trying to rebuild my strength and lung capacity after a frustrating winter, I planned to do a nearby hike on a trail I knew would be in good condition. But I’d seen road cyclists all over the area, and a last-minute check showed that the road I needed would be closed for our annual cycling race. So I fell back on my old favorite trail, an hour away on the west side of the mountains.

There was a brand-new city SUV, a Toyota Highlander, parked at the trailhead, and the trail log turned out to be unusually entertaining. On April 17, a party of two from Missouri had taken up four rows with an extended rant using a red pen that they’d obviously brought for situations just like this. According to the Missourians, the wilderness map shows a good trail here, but the trail is actually “very dangerous for backpackers” and “constantly giving out when you walk on it”. They reached the second creek, where another trail branches off, but found “the trail does NOT exist anymore for the past 50 years” and therefore they “tore off the sign”. Adding insult to their perceived injury, they found no Rainbows or Gila Trout in the creeks, and they admonished the Forest Service to “get out the trucks and start cutting some trails!!!

The next log entry, a week later, simply said “Trail is great! Grow a pair of ovaries” with an arrow to the previous comment.

Shaking my head, I started down the trail into the first canyon. The Missouri rant was so over the top, I figured there was a good chance it was a prank. I’d made a prank entry myself last year after someone else had criticized the trail condition. This is a trail of contrasts – unlike most other trails in our wilderness, it’s been easy to follow and clear of overgrowth, deadfall, and blowdown throughout the three years I’ve been hiking it. But its route involves very steep ascents and descents that make it inherently the most challenging hike I do.

I knew it was going to be a hot day – record heat was forecast throughout the Southwest, with temps in the mid 80s in town. I already had my shirt unbuttoned before I reached the canyon bottom, where I expected the creek to be in flood – hence I’d worn my waterproof boots. I strapped on my gaiters just to be safe, but turned out not to need them.

The trailhead log showed 18 visits in six months, and most of those were day hikes which typically end after only a mile, here at the first creek crossing. Even the backpackers often get no farther than the campsite less than a half mile upstream. But I was hoping for the full workout.

The flies started bugging me as soon as I began climbing the switchbacks and started to sweat, so on went the head net, which I kept lowering and raising as needed for the rest of the day.

Up on the rolling plateau between the first and second creeks, there’s enough loose dirt to read tracks. Equestrians had been up here months ago, but there was only one recent human track – some kind of sneaker. And at the west end of the plateau a dog – a big shepherd mix – appeared, barking, followed by a trail runner, a big girl who looked like a college student. She raced past me as I asked how far she’d gone – “to the West Fork!”. She was the Toyota driver, and I wondered if was her parents’ car – it would be a spoiled college student who owned a fancy new vehicle like that. Most surprisingly , she wasn’t carrying any gear – she might’ve had a small water bottle in her hand, or not. I spent the rest of the hike marveling at someone who would run more than 11 miles on a trail with over 3,000′ of elevation gain, on one of the hottest days of the year, with no more than a liter of water – if any!

I was even more perplexed when I started down the rock-lined switchbacks into the canyon. I did three months of trail running in our Mojave Desert mountains back in 2002, when I was in peak condition, and I recall only being able to run up about 300′ of elevation gain on good trail before slowing to a fast walk. And when I reached steep, rocky sections I was definitely walking. This trail has two sections of switchbacks, each dropping/climbing 1,400′, with sharp, loose rocks underfoot for much of the way.

I simply didn’t think it would be possible for anyone to run either up or down those sections. It would be like running in a road with a dump truck ahead of you pouring a layer of bricks in your path. Crazy.

I reached the beautiful floodplain of the second creek and discovered the Missourians were not pranking after all – they’d not only torn off the old trail sign, they’d either stolen it or hidden it somewhere. This was even worse than expected. What kind of hiker destroys a trail sign?

I’d already known their excuse – “the trail does NOT exist anymore for the past 50 years” – was false, because I’d hiked that trail several times in the past, for over a mile upstream, to a beautiful swimming hole. I began to think hikers – and especially backpackers – should have to pass a test in order to qualify for using our trails. Apparently what’s happening is that in our age of social media and parents who assume schools will raise their kids for them, naive, ignorant, and poorly socialized young people have unlimited free access to unreliable information online, and conceive wilderness trips they’re completely unprepared for. And when the reality doesn’t match their preconceptions, they react like Donald Trump.

In this case, the result was sad, because those historic trail signs are not easily replaced. And I hold outfitters like REI partially accountable, because their products and photo spreads set false expectations for conditions in the burn scars that now cover much of our public lands.

Despite being in the midst of a heat wave, I decided to bypass the swimming hole and continue across the second creek, over a shoulder toward the third creek more than a mile and a half away, because that would yield a much better workout. The third creek is a little too far for a day hike, but I did get as far as I’ve ever gone before, to the edge of a cliff a couple hundred feet above the third creek. And I paid for it on my return.

I found no tracks other than wildlife on this stretch of trail – I’m the first hiker here in the past six months.

It was the last day of April, but it felt like mid-June. After turning back, I could tell that despite bringing four liters, my drinking water was running low. But there were two creek crossings on my return where I could refill if needed.

Starting up the switchbacks, I began to feel the strain on my body, and thought about that girl again. I was having to stop about every 50 feet to catch my breath, and my whole lower body was on fire. I figured she must’ve known in advance that this is one of our few trails that are clear of overgrowth and blowdown in our current fire/climate regime – how could you run in shorts through thorn thickets and fallen trees? But in general – what kind of human would run up and down a steep trail like this, on loose, sharp rocks, with little or no water? It still boggles my mind.

The climb took me over an hour, and I finally swallowed a pain pill while crossing the rolling plateau.

I ran out of drinking water on the descent into the first canyon, but I decided not to refill at the creek – the final ascent to the trailhead is only another mile in the shade.

The pill kicked in and I felt much better climbing out of the first canyon – although it still feels like it will never end. At 14 miles and 4,400 feet of elevation, this was the longest hike and biggest climb I’d done in the past six months! Hopefully it’s another step forward in the recovery of my lost capacity.

April 24, 2023

Trails of Ozymandias

It was late April and I figured my favorite high-elevation trails would be sufficiently snow-free. But a combination of snowmelt flooding and blowdown in this windy season had left so many inaccessible. Plus, I was losing too much productive time to hiking and chores, so I needed to stay within the local area – leaving only one good option, the crest trail east of here.

The day was going to be warm but partly cloudy, and up on the crest it should be cool. Getting an early start, I drove 12 of the 40 miles east, only to be reminded that the highway over the range is closed – cracks in the roadway indicate a potential failure, our climate taking its toll on the works of man.

Another option, closer to town, would take me through exactly the same kind of terrain I’d been hiking all month. The early start meant I now had an on-time departure. So I decided to violate my better judgement and drive over to Arizona after all. I would decide on a hike once I got there.

To my dismay, when I entered the range, I found cars and people everywhere. But there was no turning back now, so I decided to take the most remote trail, which involved a very rough high-clearance 4wd drive up a rock-lined canyon. Hopefully that would discourage the riff-raff.

But I found two cars parked at the turnoff – hikers walking up the canyon since their vehicles wouldn’t handle it. And approaching the most difficult section, I saw a well-dressed, distinguished-looking older man, standing in the road ahead, staring and frowning at me. I smiled and waved, but he just kept frowning back, refusing to move. It was really hard to drive around him safely, but I smiled and waved again, while he kept staring and frowning.

I parked and started up the trail. After a quarter mile, I met a twenty-something guy coming down, carrying binoculars but without a pack. I asked if he’d gone to the waterfall, and he said he was looking for birds. Of course! All these people were birders, here for the big spring migration! That’s why the old guy in the road had been pissed at me. Birders treat everyone else as an obstacle in the way of their competitive obsession.

But this was good news for me – birders aren’t hikers, and would stay within a mile of their vehicles. I had the wilderness to myself.

The winter of pain and trail closures had weakened me, so I felt slower than usual. And even on the lower, eastern segment, our windy season had snapped living pines and firs that now blocked the trail.

Blowdowns continued when I reached the hanging canyon – our prevailing southwest winds funnel through here from the saddle above. And just below the crest, a 100-foot-tall fir had been snapped off right next to the historic Forest Service cabin. It was a miracle the log cabin hadn’t been crushed – the tree fell less than a foot from the corner. But its branches damaged the roof, which will need repairs in the next month or so to avoid water damage.

I’d been climbing with my shirt unbuttoned, but the saddle is a wind tunnel – when I reached the crest I encountered a bitter gale and had to pull on both my sweater and shell jacket. Clouds were building and casting cold shadows too. But I fought my way south – I thought I had just enough time to reach the saddle I’d hiked to six months ago, when our monsoon was transitioning to winter snowstorms.

The last stretch of trail was where I found the most remaining snow, plus more blowdown – and this is the rockiest part of the trail. In my weakened state, I’d been slipping, stumbling, and even falling a few times so far, narrowly avoiding injury. I found a couple of faint bootprints on the upper trails, but their treacherous condition is discouraging most hikers.

On the way back, I thought about how, through a combination of our ecological ignorance, hubris, and a changing climate, nature is systematically destroying the works of man. From the eastern highway to trails and a wilderness cabin, my whole day told the same story. And these aren’t skyscrapers and palaces we’re talking about – these are basic infrastructure even the most environmentally-conscious of us take for granted. Like it or not, none of it’s sustainable.

The descent was really hard on my knees – more evidence the long winter weakened me. I was hobbling by the time I reached the vehicle. And to add insult to injury, the birders were running the cafe staff ragged – I had to wait an hour for my order while they were deliberating over their fine wines. And they’d taken all the rooms at the lodge, even on a Sunday night. I had to drive all the way home in the dark, arriving exhausted at 10pm – having put in a 14-hour day to accomplish a 7-hour hike.

April 16, 2023

The Map Is Not the Territory

Another warm, clear Sunday. I wasn’t sure if the snow had melted yet from my favorite high-elevation trails. But studying the map for the trail I’d aborted last Sunday, it looked like I might be able to use it to reach a 9,700 foot peak farther east. At almost 19 miles out-and-back it would be a long shot, depending on trail conditions and my endurance. But the map showed it as part of the CDT so I figured it would be in good condition.

On the drive east, a deer suddenly raced across the highway in front of me. Then another followed, slamming into the side of my vehicle. I slowed and pulled over, glancing in my rearview mirror. The deer that had hit my car was rolling on its back, kicking its legs. Then it jumped to its feet and ran off, following the first deer, as if nothing had happened. More deer followed, all racing across the highway in single file. It was like a lottery to see which of them would get hit. And it was only a little over a year since my last, and first, deer collision. Fortunately for me, there was little damage this time.

The first trail – shown on some maps as the “old CDT” – climbs almost 1,500 feet to a saddle where other trails branch off. Nearing the saddle I met an older couple with an off-leash dog. The dog barked hysterically at me, and as usual they struggled to leash and subdue it. I asked them if they were enjoying the hike, but they ignored me.

I had three choices at the junction. The left-hand branch was the branch I’d hiked last Sunday – from the opposite direction. Straight ahead a trail went down the drainage, and a sign marked it as the “New CDT”. Interesting. The right-hand branch I planned to take, shown on my map as the CDT, had faint tread traversing the slope, but whoever had put up the “New CDT” sign had blocked this trail with logs.

I started up it anyway, but it turned out to be a disaster. Frequently blocked by deadfall and blowdown, with many places where there was simply no sign of a trail. I continued as best I could, but after 3/4 of a mile I came to a broad, shallow valley where the trail completely disappeared. I cut for sign in a circle about 100 yards in diameter but found nothing. The trail shown on the map as the CDT simply didn’t exist on the ground.

So I returned to try the “New CDT”. It started okay – a couple had even gone down it before me – but it rapidly turned into an erosional gully with no sign of a trail. The farther down I went, the worse it got, turning into a debris flow choked with fallen logs. So this is the new CDT? Good luck, through hikers! Again, I fought my way 3/4 of a mile down before giving up and turning back.

I still had a couple hours left for hiking, so I decided to go up the left-hand branch a mile or so – the one I’d hiked last Sunday – just for the exercise.

Back home, I checked the official CDT website. They show the trail that no longer exists as the official route. This year’s crop of through hikers will likely be really confused. If they take the “New CDT” they’ll end up fighting their way down a flood-damaged canyon with no surviving trail, adding 15 miles and several days to their trip. I hope they’re carrying enough food!

April 10, 2023

Smoke Alarm

It looked like spring was finally here. Still hoping to regain more mileage and elevation on my Sunday hikes, I decided to try an area in the high mountain range east of here, a range that had been off limits for months due to heavy snow.

I’d always assumed the trails on the west side of the range could only be reached after long, slow drives on poorly maintained dirt roads. One of those roads actually reaches the crest, at 9,500 feet with the highest peak only a mile and a half farther – more driving and less hiking is definitely not what I need.

But further map research over the winter had revealed a couple of high-elevation trails that should be little more than an hour’s drive from home. They topped out over 9,000 feet, so I expected some snow, but one had mostly southern exposure, which should be bare by now.

So I headed over there. And ironically, just like last week, I’d ignored the fact that the access road starts by crossing a river, which of course was in flood now.

So there I was, 45 minutes from town, blocked and in search of a second option. I’d previously hiked three trails in the vicinity and had no desire to repeat them. But a little over three miles north there was another dirt road I’d been curious about for a long time. It was known to be challenging to drive and would ultimately yield more driving time and less hiking time in my day. But it didn’t cross a river, and it featured several trailheads – including the CDT, which should be in better shape than the now-brutal Forest Service trails.

The road is historic and fairly legendary. Built originally by the military in the 1870s, it was improved in the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps, and during the same period, it became the narrow corridor between our two huge wilderness areas.

The first stretch runs up a mesa toward the distant crest and goes quickly. The first trailhead was well-marked, and I set out on a surface pockmarked by hooves. Within a half mile I came to a side drainage, with a view toward the river canyon, downstream to the right. And I saw smoke, drifting through the pinyon and juniper.

As I stood watching, the smoke moved off and dispersed. I followed the trail around the head of the drainage and came to a junction where a branch trail went down toward the river. I saw another cloud of smoke drifting just below the canopy. Damn! This is the dry, windy season when most of our wildfires start – had I avoided a flood only to be turned back by a forest fire?

Today’s air was perfectly still, the sky was mostly clear, and we hadn’t had any storms for weeks. But the last couple of days had been cloudy in town – maybe there’d been dry lightning over here?

There were isolated remnants of a burn scattered around me. They looked recent but not fresh. This was on the edge of last year’s mega-wildfire. I watched carefully and couldn’t see an origin for the smoke, so I headed down the branch trail. After about a hundred yards I saw a meadow off to my right in the bottom of the drainage and made my way over there for a better view. Again, isolated charred logs and patches of ash-covered dirt, and another little cloud of smoke drifting through the trees. I touched a charred log – it was warm, but it was in the sun. I hadn’t smelled smoke yet at any point.

I decided to return to the main trail and keep going, while remaining vigilant. Maybe I’d get a better view into the river canyon, if that was the source of the smoke.

After climbing a steep, rocky slope, I reached a sort of grassy plateau dotted with junipers, and suddenly noticed another wisp of smoke drifting through the crown of a low tree. What the hell?

In the distance I could see what appeared to be the edge of a precipice, so I headed over and found myself atop the rimrock of the river canyon. But there was no smoke anywhere to be seen. So I returned to the main trail and climbed still higher.

Eventually I had a view back over my approach. And the first thing I saw was a cloud of smoke which appeared to lie in the side drainage I’d first encountered. There was an active fire, burning toward my route back!

I took off running down the trail. But with 4 liters of water in my pack for warmer weather, I couldn’t really run on the rocky stretches without risking a broken ankle. My heart was pounding, even when not running. If the trail was on fire, I’d have to try to bushwhack around it. Or reverse and go the long way around, connecting with other trails to reach the road much farther north, fifteen miles or more. Meanwhile, my vehicle might be destroyed by the fire.

I was exhausted when I reached the side drainage – and there was no sign of smoke. I began to wonder if maybe the “smoke” I’d seen had actually been dust raised by the passage of a vehicle on the road, a mile farther away. In any event, I had no interest in retracing my steps after that desperate run downhill.

The next trails were about 7 miles north, past the gnarliest part of the old road. It climbs in hairpin twists up a tall ridge, then winds down in more hairpins into a dark, narrow, rocky canyon, where it basically turns into a path up a debris flow, crossing and recrossing a network of flowing creeks, where my vehicle slowly rocked over small boulders, humps and ruts, averaging less than five miles per hour.

Finally the road left the creek and climbed through more hairpins over another high ridge, and I emerged in the north country, with a long view north and the main crossing point of the CDT. I hadn’t really studied the topography of any of these trails that trended eastward toward the crest of the range – starting from trailheads a little below 8,000 feet, I just figured they would go up over ridges and down into drainages, while gradually rising toward the crest. I knew I was about 12 miles from the crest and wouldn’t reach it in the time I had left – I was just exploring, in preparation for a better-planned return.

As I’d expected, this part of the CDT was in better shape than Forest Service trails – it’s maintained annually whereas a few forest trails are cleared once or twice a decade, and most are simply abandoned. But I couldn’t find any recent tracks, and heavy growth from last summer’s monsoon meant that tread was nonexistant in many places. I had to imagine a path forward much of the time, but I’m getting pretty good at that!

The first milestone shown on my map was called “Rocky Point”, which I was hoping would offer a vista across the landscape. But I hadn’t checked to see how far it was, and the trail just kept climbing, and climbing. This area had burned patchily, and I could sometimes see north between the trees, but that wasn’t very interesting. Finally I spotted a peak with talus slopes ahead – maybe that was it? But the trail turned, and climbed around its flank, where I finally got some longer views west across country I already knew well.

Past the talus peak, the trail climbed toward outcrops I figured had to be Rocky Point. It turned out to just be a slope dotted with outcrops. I could see a much taller peak in the distance, with a trail traversing across it. After making my through the rock outcrops and across a saddle, I found myself on that trail. I was glad to be gaining some good elevation. I knew this trail would eventually connect with the one I’d attempted earlier, but I didn’t know how far I would get in the time I had.

The trail eventually reached its high point, a little below 8,800 feet, crossing another saddle into a shaded north slope where some patches of snow remained. There, the trail condition deteriorated farther – but I’d been noticing faint bootprints and finally confirmed that one medium-sized person had been here before me, maybe as long ago as last fall, before the snows. That’s another thing about the CDT – despite all the effort put into maintaining it, it tends to see little use outside the window of late-April to early-May, when most through-hikers start north.

Even harder to follow now, the trail began to gradually descend, across saddle after saddle, until in a shallow drainage, I came upon the junction with the other trail. Nothing spectacular, but my time was up.

As soon as I turned around and started back, I discovered that the downhill run I’d done after that early-morning smoke scare had damaged my left knee. It was like having a knife in my knee, so I now only had one good leg to hike about 5 miles downhill on.

Despite the excruciating pain, this had been a beautiful day and a pretty nice trail. I wish it had better views of the crest to the east – all I had was narrow glimpses through surviving stands of conifers. But the west flanks had been cleared in past wildfires, and were so steep that the traverses were impressively dizzying.

Another thing that impressed me was the past trail work. In level spots this trail had often been outlined with rock berms, and on traverses and switchbacks it had been built up with retaining walls that must have taken many days to construct, sometimes using rocks weighing over 200 pounds.

Still, the drive is a little too far, and the accumulated elevation gain turns out to be too modest, to encourage a return visit.

But back home, studying my photos, I realized something I should’ve guessed on the trail, something I learned when I first moved here, and had since forgotten. Tolkien’s ents aside, we think of trees as passive and immobile. But junipers can forcibly eject their pollen in explosive clouds. The “smoke” I saw on that first trail was actually juniper pollen. And the smoke I saw lying in that drainage had to have been dust from a vehicle on the road. That knee damage turned out to be pointless.