Max Carmichael's Blog, page 31

May 17, 2017

The People Who Adapted

Art on the Rimrock

From the Mojave Desert, I traveled northeast to the Colorado Plateau, where I camped among pinyon and juniper near the rim of a sandstone canyon. My campsite faced the setting sun across a broad, shallow basin blanketed with sagebrush.

In the morning, I drove farther into the back country, passing prairie dog colonies with their popup lookouts, and followed a trail down from the top of a mesa to a rimrock escarpment. Hundreds of feet below, a creek opaque with grey-green sediment raged, carrying water down from snow on distant peaks.

Near the end of the escarpment, ancient people had made pictures in the sandstone. These pictures are attributed to farmers from a thousand or more years ago who lived in earth houses, whose remains are found all across Utah, often under modern towns and cities.

Village in the Canyon

During completion of an interstate highway, a boy who lived in a canyon in its path told his father about ruins he’d seen on a hill that was being attacked by bulldozers. Eventually, the bulldozers were temporarily halted and a team of archaeologists surveyed and excavated the hill, finding the largest known village site of the mysterious farmers who are believed to have created much of the prehistoric rock art in Utah.

After the village site and its house ruins were excavated and artifacts removed, construction of the interstate highway resumed, almost completely destroying the hill and its ancient village. In partial compensation, the state opened a museum to store and display artifacts and educate the public about the vanished community.

The Canyon

The Art

Anglo settlers have always known this canyon to be rich in rock art.

The People

Apart from the rock art attributed to them, the ancient farmers are known for their earth houses, which archaeologists misleadingly call “pit houses.” This term reflects the Anglo-European bias in favor of technologically advanced societies that attempt to “rise above” nature and dominate the earth. Anglo archaeologists considered the ancient farmers more “primitive” than their Anasazi neighbors who built cliff dwellings far above the ground; in comparison, these primitive farmers seemed to be living underground in pits like animals.

But as I noted last fall in Closing the Circles, these “pit houses” were actually mostly above-ground, and both spacious and comfortable. Unlike the “pueblos” of the Anasazi and modern Indians of the Southwest, these earth houses were not defensive, indicating that their populations had achieved a peaceful existence. The boxy, densely populated “pueblos” with their dark, cramped rooms would more accurately be termed “fortified apartment blocks,” built and inhabited by a society that was out-of-balance, and fearful, like ours.

But most importantly, the earth houses of the ancient farmers were supremely adapted to their environment. These people did not try to engineer their habitat on an industrial scale like the Anasazi – or like our own society.

Of course, the best evidence of this society’s success would be seen not in their houses and other artifacts, but in themselves, their gardens, and the health of the natural ecosystems they inhabited, all of which seem to be lost to us now. But maybe not completely lost – modern tribes may be directly descended from the ancient villagers, and recent excavations in other parts of this area are showing that some of the ancient farmers’ fields and irrigation networks were used continuously into historic times, when they were appropriated by early Anglo settlers.

As the museum exhibit asks, “What can these ancient people teach us?” Unlike us, they put the well-being of the community above that of the individual. They lived in harmony with nature. And instead of trying to control nature, they adapted their way of life to changing conditions in a challenging environment.

As a result, they thrived for a thousand years in this place, sustaining a larger population than we do there, even with our advanced technology and vast wealth. But, also unlike us, they sustained their traditions of hunting and gathering, so that when conditions changed dramatically, instead of fighting nature, they could temporarily set aside their village farming way of life and became nomadic foragers and hunters.

The Girl

For me, the centerpiece of the museum was the multi-media story of a farmer girl who had died at the age of seventeen. From her damaged skeleton, forensic scientists had reconstructed the girl’s appearance and her likely life history, archaeologists had added cultural and societal context, a sculptor had created a life-size likeness of the girl, and a girl from a nearby modern tribe had voiced her long-forgotten story.

I’ve taken the liberty of creating this abridged version of the girl’s story, omitting some technical details and modern perspectives that can be found in the full museum version:

The Modern Nation

Anglo homesteaders came in advance of the modern nation, but within a century the nation had caught up. Its bulldozers razed the hill of the village, and its freeway paved the floodplain where the villages kept their farms, so that now the valley and its once-bustling community is merely a passing glimpse from the closed windows of the racing metal boxes rushing urban Americans from city to distant city.

I was told in the museum that Native Americans in the surrounding areas were outraged, and a native elder placed a curse on the Department of Transportation, leading to a series of mishaps and tragedies, and pleas from the government that the curse be removed. And later, laws were passed to prevent this sort of cultural destruction. But laws can be overturned, and arrogant, domineering nations seldom last as long as this community of People Who Adapted.

Homeward Bound

On my way home, I stopped in one of my favorite mountain ranges, at the far eastern edge of the territory of my favorite Indians, the heirs of the ancient farmers. I pushed my little truck dangerously through a raging stream to a clearing under tall green cottonwoods, below a cliff of layered sandstone.

When I got out of the truck, I discovered the ground was covered with shelled pine nuts. The modern Indians had used this very spot to process their harvest, a harvest they’ve sustained for thousands of years!

Crossing the last range of mountains toward home, I drove through a sleet storm at 8,500′:

May 13, 2017

The Original Organic Abstraction

In my earliest childhood, I was surrounded by the organic abstraction of midcentury textile patterns:

When I started experimenting with Sumi ink on paper in 2011, organic abstraction flowed spontaneously from my brush:

Then, a few days ago, I visited perhaps the most interesting rock art in the Mojave desert, in a lush canyon oasis on the sacred mountain of the Colorado River tribes, where their creator god began his journey down the river. During my visit, I encountered the kitsch of white peoples’ religion, I picked up their abandoned plastic trash, and I convinced an Anglo family to stop desecrating the site with their loud pop music.

May 11, 2017

Return to the Lost World

First Glimpses, and the Dream

I first saw the Lost World in April 1994, from high on the central ridge of the mountain range:

In a large and complex range, with many interior basins, this is the largest: a valley eight miles long and four miles wide. And since the passage of the Desert Bill in October of that year, it can only be legally accessed on foot.

But the barriers in the way of entering this remote valley are even greater. The Lost World is almost completely surrounded by eighteen miles of high, steep ridges and peaks. Its mouth is little more than a mile wide.

That opening at the south end of the valley is two miles from the nearest legal road, a poorly-maintained track through deep sand. From the road, it’s a two-mile hike uphill across low desert through sparse creosote scrub. There are other points where a legal road approaches within two-to-four miles of the valley, but most of those approaches involve a strenuous climb over the intervening, steep, tall ridges that almost completely encircle the valley.

I returned for another view in October 1994, and again in December 1998. I was clearly becoming obsessed with that vast, unexplored, difficult to reach valley:

Many years passed, in which I dreamed of somehow getting back in there. I remembered that in 1992, a friend who studies the wild mountain sheep had taken me in a helicopter over the north end of this valley, and across a deep canyon on the east side where I could see lush vegetation. He’d also given me a map of water sources that he’d made in a very wet year, and the map showed that even in a good year, the Lost World is devoid of water sources except in two places, both near the mouth of that canyon we’d flown over. So unless I visited after several years of heavy rainfall, I’d need to carry my own water for miles into the valley. And the warmer the weather, the more water I’d need to carry.

2015: The Northeast

The barriers to access, and the lack of water, stood in my way for over twenty years. It wasn’t until 2015 that I first set off to enter the Lost World, hiking up a smaller exterior basin on the east and over a high, steep ridge, to end up near the mouth of canyon we’d flown over. Unfortunately, the desert was still in a deep drought, and I had ended up hiking into a heat wave, so the springs were dry and I only had enough water to get back out. So I was only able to explore about two miles of the main valley floor. However, beyond my wildest expectations, I discovered potsherds, worked stone, and petroglyphs – prehistoric rock art of the Old Ones – showing that people had spent time over here, in wet years when there was reliable water nearby, probably near those very boulders.

In 2016, I did an eight-mile round-trip hike from my land in the north, up to a ridge that overlooks a northwestern corner of the Lost World. There, I had a limited view of the valley’s eastern wall, including part of the area I visited the previous year. I wanted to go back, but there was a wall in my way.

The routes I took in and out of the valley in 2015 were extremely rugged, prompting me to take a closer look at the alternatives. One was two miles to the south, but looked even more rugged on approach. Another was far to the west, and would involve a long hike around and over a narrow pass that opened into the lower, southwestern edge of the valley. Again, I would have to carry all my water. And this spring, I finally found myself in the desert again with a forecast of cool weather and rain, the best conditions I could hope for.

2017: The Southwest

I had a three hour drive to get near the pass, including about forty miles on paved highway, interrupted by several miles of detour on dirt roads, and ending on thirty miles of poorly-maintained or unmaintained, and heavily eroded, gravel, sand, and bedrock tracks. On the way, before I got to the really bad parts, I had to stop and deflate my tires for traction in sand. So I didn’t arrive in the mountains until early afternoon. Once I’d located a campsite, I did a two-mile hike to the mouth of Mesquite Canyon where I knew there’d be afternoon shade at the foot of a short cliff. There, I encountered abundant cottontails, jackrabbits, quail, and mourning doves, and anything red I carried was an endless curiosity for hummingbirds.

By the time I returned to camp, heavy, dark clouds had formed over the northern part of the range. I gathered branches for firewood and grilled all the meat I had left from last week’s shopping. Just as I finished laying out my bedding, it began to rain.

I quickly gathered my things up and retreated into the now-crowded cabin of my truck, where I watched and listened to heavy rain on the metal roof and lightning and thunder eight to ten miles to the north. It rained intermittently hard for about forty-five minutes. Then I unpacked all my bedding and laid it back on the wet sand. It was so windy, I had to turn my sleeping bag around, but after that, I finally got a good night’s sleep.

I woke early the next morning, and was able to load my pack and start hiking toward the pass by 9 am. The weather was perfect for conserving water – it would be in the 60s all day. I figured I would aim to be back by 6, for a total of nine hours of hiking. Over open ground, I could theoretically make eighteen miles in that time, but I knew I’d be stopping a lot for photos and side trips. And “open ground” is misleading in desert scrub, where every dozen yards you need to detour around a sprawling creosote, catclaw, or cactus, around an even larger granite boulder or outcrop, or down into and up out of a deep wash with steep banks of loose sand.

After the first mile of gentle uphill slope, I entered the pass itself, two miles of traversing across the foot of a steep ridge, with views of distant mountain ranges to the south between smaller, isolated peaks that form the southern walls of the pass. This pass is a really beautiful and interesting area in itself, but I was on a mission and didn’t linger much.

Finally I came out into the southwest side of the Lost World, and rounded an outlying shoulder of ridge to get my first view to the north and the extent of the big valley. Both sides of the valley are scalloped by cross-ridges and tributary canyons, many of them sizable basins in themselves, but I intended to march north past as many of these as I could, to see how far up the main valley I could get in the time I had.

Of course, the most thrilling aspect of visiting a place like this is the fact that you’ll be the only human in a huge area, perhaps the only human visitor in decades, and you will see no buildings or vehicles or ruins or any other sign of human life other than the prehistoric petroglyphs and tiny artifacts I found in 2015. I hoped to find more rock art, so I did stop and explore any prominent outcrops or boulder piles along my way that exhibited desert varnish, the black bacterial weathering that provided a canvas for the Old Ones.

In the end, I found no rock art – not surprising, since according to my biologist friend there are no springs on the western side of the valley – but I did penetrate to the northern half of the valley, where I had a view of the entire northern ridge line, including all the points where I’d looked down into the valley since 1994.

What a glorious day! I found no shade on my route, but the weather was cool enough that I didn’t need any for a change. There were so many birds out, everywhere, following me, curious about what I was doing, making noise if they thought I was threatening a nesting area. By the time I had rounded that last shoulder of ridge and taken my pictures to the north, it was time to quickly grab a snack and immediately head back. My left foot and right hip were hurting pretty bad, so I downed a couple of painkillers as well. As glorious as the day was, and as beautiful as the valley and pass were, it was a fairly painful trek back. I figured my round-trip hike to have been about thirteen miles, the longest hike I’d done in seven or eight years, since my hip condition began to deteriorate, and I had surgery.

By the time I returned to my campsite, the sun was going down, and I was exhausted, sore, and thirsty. But as I approached the back of my pickup truck, I heard a loud buzzing, and discovered that hundreds of bees were swarming the bed of my truck. I suddenly realized they’d been attracted to water that had pooled in the pickup bed from last night’s rain, since the truck was parked downhill on a slight incline. All my stuff was locked in that truck. What was I going to do?

I knew they could be Africanized “killer” bees, which have been known in this mountain range for decades. But I was desperate. I thought if I could get into the truck somehow, I could drive up the wash so that the water would drain out, and maybe the bees would lose interest. I skirted the edge of the swarm to see if bees were moving around the doors. They were, but they seemed to come and go on the passenger side, so that I might be just able to race over, unlock the door, jump in, and slam it closed without any bees following me. I didn’t give myself time to think, I just set down my pack, took the field glasses from around my neck and set them on the sand, and pulled the camera out of my hip pocket and also set it down on the sand. My folding chair was leaning against the pickup bed, so I grabbed it and moved it away, careful to move slowly so I wouldn’t anger the bees. Then I watched the bees moving past the passenger door, and made my move when I saw a short break in their traffic.

I made it, and got the door closed without letting any bees in! But before leaving that morning, I’d packed the truck willy-nilly with all my unrolled bedding and everything else I didn’t want to leave outside, so now I had to pack everything into the narrow space behind the seats, and awkwardly maneuver over the brake and shift lever into the driver’s seat. Finally, I drove a hundred feet away, up the main wash, left the truck, and cautiously walked back over to the campsite to get a drink of water from my pack.

But now, a second group of bees had separated from the main group and were swarming all over my pack, my camera, and my field glasses! My heart sank. I was so tired, so thirsty, so sore. How was this going to end?

I walked away up the wash, a hundred feet from the swarm, and sat down on a rock ledge. But soon, a bee followed and found me, so I moved another hundred yards out into the desert. I was alone in the middle of nowhere without water, food, or shelter, all of which the bees now controlled.

And even way out there, another bee tracked me and started harrassing me, so I had to get up and keep moving. I made a great circle out into the desert, thinking I’d come up on the truck from the opposite direction and see if they were still swarming the bed. On the way, I remembered that beekeepers use smoke to control hives, and I remembered I had a lighter in my pocket. I knew that dead yucca blades generate a lot of smoke, and although there were few yucca in this basin, I’d seen one up the wash, so I detoured over there, pulled off some dead blades, and scrounged some dead grass for tinder. Soon I had a smoking torch.

By the time I returned to the truck, there were only a few, sad-looking bees crawling along the bed. The sun had dropped behind the western ridge and it was noticeably cooler. When I walked over to camp, I saw only a few bees, so I started a fire in last night’s fire ring. The wind was blowing north, so smoke from the fire would keep any remaining bees away from my pack. And soon, the remaining bees were gone, and I was able to get a drink of water out of the pack, and to drive my truck back over.

I figured that with the area in shadow, it had probably gotten too cool for the bees, and they’d headed back to their hive, which was probably up Mesquite Canyon, or even over the high ridge in the next drainage. I could probably have just kept walking circles out in the desert and waited for them to leave. But the experience had really spooked me, and turned me off camping in this area. So I packed up and drove outside the mountains onto the vast western alluvial fan, where I camped that night at lower elevation on desert pavement, among very sparse scrub, with a sunset view of bright sand dunes and distant, dark ranges.

In the morning, there were just a few bees left crawling feebly around the bed of my truck. I planned to spend the day and night in town resting my foot and hip and restocking for my next attempt to reach the Lost World via an eastern approach.

2017: The East

I had so much business in town, I didn’t get back to the mountains until mid-afternoon the next day. On the way down the long dirt road past the eastern side of the range, I saw trucks blocking the way ahead, and came upon a young woman urging a tortoise across the road. She turned out to be a recent biology grad consulting for the gas company, doing tortoise training for their pipeline maintenance personnel, big guys who hovered awkwardly in the background.

I encountered two more tortoises on that road – probably a record – because the tortoises know when rain is coming, and emerge from their burrows to drink. Eventually I reached my destination and scouted a place to leave the truck opposite the canyon I was hoping to use as a route to the Lost World. Then I loaded my pack and headed up this basin I’d never explored, toward a spring I’d long heard about but never visited.

It turned out to be a mostly overgrazed bajada of soft sand undermined with animal burrows, a slow and uncertain walk uphill, but it was a cool day and rain clouds were gathering all across the desert. I was carrying a rain shell and a plastic tarp to throw over my pack, and as always was actually hoping for rain. I’d started at 2 and wanted to be back by 6 to look for a campsite, so I could theoretically cover as much as eight miles round-trip.

At the head of this basin is a giant formation of granite that looks like the Dark Tower of Barad-Dur in the Lord of the Rings, abode of the Evil Lord Sauron, so I came to think of this area as the Canyons of Mordor.

The ungrazed lower part of this basin was rich in biological soil crusts, and as I got farther in, I came upon some of the biggest silver cholla I’d ever seen. Then I encountered more birds, who teamed up and challenged me in groups, flying straight up and flapping their wings at me, showing off their dramatic black-and-white banding.

Finally I reached the head of the basin and dropped down into the main wash, which curves out of sight below the towering ridge line, which is dauntingly stony. I’d seen lots of old cowpies out in the basin, and now I came upon some abandoned plastic piping, indicating that ranchers had fed the spring water down for their cattle at some point.

Then I came around a bend of the wash, saw a big boulder covered with desert varnish, and realized some of the patterns on the rock had been made by the Old Ones. I was surprised, since friends who knew of my interest had visited this spring and hadn’t said anything about the art.

I continued up the wash, and found lots more abandoned piping, and thickets of invasive tamarisk I had to fight my way through. The canyon became steep, narrow, and winding, and there were many pouroffs and blockages of house-sized boulders that had rolled down from above, in addition to thickets of catclaw and tamarisk. The surrounding slopes, of dark, ancient granite, are topped by many strange pinnacles that our imagination can easily make into recognizable forms. But it’s a world of stone, even more so than other parts of the range.

This is supposed to be an important spring, but the higher I climbed, the more I despaired of finding water. And the ridge above wasn’t getting any closer, it was just getting steeper and more forbidding. This would not be a good route into the Lost World. Then clouds began pouring over the peaks, and I knew it was time to turn back. A few drops of rain were beginning to fall and I was getting cold.

By the time I got back to the truck, it was raining lightly. I was anxious to get to my favorite campsite – in fact the only campsite – on this side of the mountains, but it was a long stressful drive at low speed over deeply eroded dirt and rocks and uphill through deep sand. It began to rain harder, and when I finally reached the site, someone else had claimed it with a big truck and loads of gear. I wasted some more time looking in vain for another site, then I gave up, turned around and drove back down to the main gravel road out of the mountains.

I headed north, through increasing darkness and intermittent heavy and light rain. Night was falling and the storm was spreading, and the road had high banks with no place to pull out. I reached a high area of desert pavement beside a smaller mountain range and was finally able to pull off under a transmission tower. Someone had camped here and left their fire circle, but it was under a damn powerline and transmission tower, and after seriously considering it, I realized I wasn’t set up to cook dinner or lay out my bedding in the rain, a situation I’d never had to provide for in the past. This was a new experience and nothing to really complain about – being driven out of the desert by rain!

I still had to stop somewhere and re-inflate my tires. I did that in the dark, in heavy rain, beside the road. It takes a half hour. I reached town, and a motel, by 9 pm, under continuing heavy rain in the desert.

Perspectives

What’s next? Well, it would be cool to explore all those side basins and canyons. But that would take multiple days, and too much water to carry. If only we’d get several wet years in a row, to recharge the fracture zones in the granite and get the springs going again. Then maybe there’d be water on the east side, and I could actually live in the Lost World for a few days. It can’t hurt to dream!

April 30, 2017

Rendezvous With Deep Time

Arrival at Night, and the First Day

I got a late start, and entered the mountains just as full dark was falling and all the stars were coming out on this moonless night. The military refueling flights were occasionally deafening as they droned though their long mechanical circles overhead, but they stopped at 10 pm. Snug in my sleeping bag, there under the glittering arch of heaven, I felt much more comfortable and at home than in my bed back in Silver City.

On the first day, temperatures were mild, with alternating wind and calm, clouds and blue sky, and I hiked up to the Shade House. There, I strung my hammock and lay reading and watching birds and pollinators move among the nearby shrubs and boulders. The clouds, some tantalizingly dark, brought temporary humidity but no precious rain. I was plagued by gnats, but at least they didn’t bite. I hiked up to the seep and found the catch basin dry – something that only happens in the deepest droughts.

A Walk Across the Bajada

The next morning I woke to a cold wind and put on layers of fleece before making breakfast and coffee. Discouraged by the drought, I thought of leaving and going elsewhere. But the sky cleared and I saw the big boulder pile 2 or 3 miles across the basin, where I knew there were inner chambers with shade from the full sun of afternoon and views out across the bajada.

The walk across the bajada reminded me that this is a special place for plants. I found dense stands of healthy bunchgrass, and surprising groupings of very different plants living together in harmony, in a desert that’s more commonly known for plants that isolate themselves from each other with chemical repellents. Many were blooming, long after the “official” annual bloom, from the tiny annuals at ground level to the tall cholla cactus and creosote shrubs. And I came upon bees, butterflies, birds, rabbits and hares, all enjoying springtime on the bajada.

That night it was so windy I had to anchor even heavy things down and turn my sleeping bag away from it, to the south. I could tell the wind was on the rise and planned to leave in the morning, discouraged by both wind and drought.

Rendezvous With Deep Time

High winds in the morning. I took my time packing up, and on the way out down the broad main wash, noticed a wedge of snow on Mount San Gorgonio, a hundred miles away through a haze of wind-raised mineral dust.

Then, just outside the mountains, I unexpectedly came upon a vehicle driven by someone I only knew as a legend – the geologist who’d discovered this place and helped put it on the international map of earth science. He was bringing some young students out, hoping they’d like it enough to resume research out here. So I turned around and joined them, and the legend gave me some glimpses of an incredibly dynamic, and incredibly ancient, story.

Here, the crust of the earth, then consisting of sedimentary – the limestones, shales, and sandstones of the Grand Canyon – and ancient metamorphic rocks such as gneiss – had been folded under unimaginable forces, and interpenetrated by younger granite rising from below, and the interfaces between the rocks were incredibly complex. In fact, much of the story remains a mystery today after decades of study.

In this migmatitic exposure, beautiful marbles had been formed, and embedded with colorful skarns in reds and greens. Layer upon layer of granites and recrystallized carbonates that had flowed over and under each other repeatedly, to be eroded across eons and exposed here for us in frozen waves and thin sheets like iced cream. Almost two billion years of the Earth’s history we hiked over, up a few hundred feet of steep mountainside.

The students hungrily scanned the rocks at their feet, but the legend kept redirecting their attention up to the deep blue of the sky behind the stony ridge, and to the special plants scattered around them, like the red Dudleya and the barrel cactus, that thrive on this particular substrate. And I pointed out my new obsession, biological soil crusts, which arise at the interface between rock and life. Easily missed knots of nondescript black matter in fissures of white stone. Subdued now in the drought, but ready to swell and glisten after a rain.

January 31, 2017

How the Middle Class Destroys the World

The Accountability Problem

The Accountability ProblemYou depend on many resources, products, and services to survive and stay healthy and happy: clean air and water, nutritious food, clothing, shelter, heating, cooling, communication, transportation, healthcare, and security. Do you know where all these things ultimately come from?

If not, how do you know whether someone or someplace is being harmed to provide for your basic needs?

The urbanized middle class – the bourgeoisie of Marxist theory – is considered the foundation of stable, peaceful society in the modern nation-state, and it’s what the lower classes aspire to. I was raised to join the middle class, and all my peers are raising their kids to be middle class – who wouldn’t?

But whereas the foundation of traditional societies is the local workers who provide basic needs, the modern middle class consists of consumers who depend on a global network of products and services that is so complex it is virtually untraceable and unknowable – and hence unaccountable.

In fact, you don’t know whether someone or someplace is being harmed to make your lifestyle possible.

How the Middle Class Destroys Society

Intimidation, Punishment, and Slavery

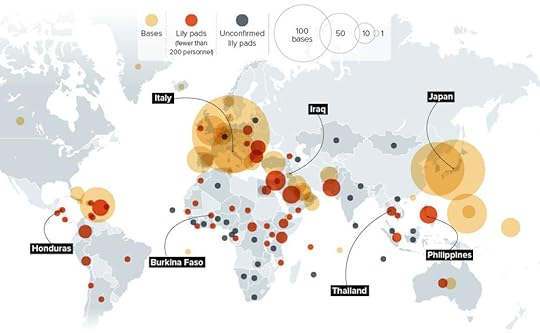

The security of the middle class depends on a nuclear arsenal capable of rendering the planet uninhabitable, a global military empire intimidating and sometimes practicing covert warfare against foreign civilians, a largely covert arms industry dominated by U.S.-based multinational corporations, and a domestic security apparatus resulting in mass incarceration of citizens, who are largely hidden away from public access in high-security prisons.

Military bases, defending the economic empire of American consumers, are imposed on the populations of much less powerful, economically disadvantaged societies, resulting in intimidation, economic dependency, and resentment.

Defending the middle class: Pakistani children killed by U.S. drone strike:

The U.S.-dominated global arms industry profits from violent conflict and human suffering:

U.S.-made weapons commandeered by ISIS:

Throughout history, traditional communities practiced restorative justice, which helps the victim and heals society. But middle class consumers depend on the punitive justice system of the modern nation-state, which harms society without helping the victims. The punitive justice system and its prison network reinforce ethnic and racial inequality, perpetuate domestic slavery, and foster social dysfunction.

Growth of the U.S. prison system during the past 40 years:

Work crew at Angola Prison, Louisiana:

Economic Imperialism

The middle class consumer lifestyle is sustained by mass-produced products and services made affordable by large corporations and long-distance distribution networks exploiting economic inequality. Products are manufactured, and services are directly provided, by blue-collar laborers whose labor is generally valued far less than that of middle-class consumers, and who live in poor neighborhoods with a lower quality of life. Middle class waste products are transported to, and imposed on, poor neighborhoods for processing and disposal.

Since major products like food, fuel, clothing, phones, computers, appliances, cars, and building materials are typically manufactured in poorer foreign countries from components and raw materials which in turn come from other, even poorer foreign countries, workers sometimes live and work in virtual – or even actual – slavery. And the supply chain for consumer products is virtually untraceable.

MarketExample of U.S.-Based MultinationalAnnual SalesCEOAnnual Compensation

FoodMonsanto15 BillionHugh Grant11 Million

ClothingNike32 BillionMark Parker48 Million

FuelExxon Mobil269 BillionRex Tillerson (outgoing to become Secretary of State)33 Million

ShelterPulte Group6 BillionRichard Dugas8 Million

TransportationGeneral Motors156 BillionMary Barra29 Million

CommunicationsApple53 BillionTim Cook10 Million

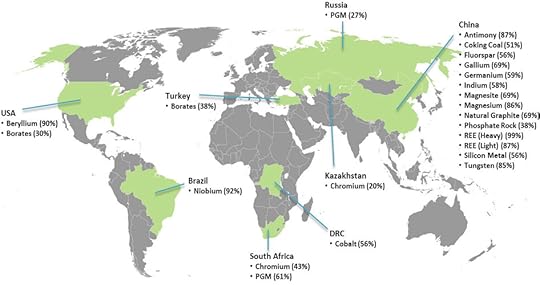

Raw materials for consumer products needed by the middle class come from distant rural communities all over the planet, where workers and their families endure dangerous conditions, toxic environments, war, or slavery:

Mining for the electronics industry in the Congo:

The urban middle class depends on services – housekeeping, childcare, food service, transportation, repair and maintenance, waste disposal, etc. – provided by lower-class workers living in poor, often gang-dominated, neighborhoods.

Gang members in East Los Angeles:

Social Division, Fragmentation, and Isolation

A college education, one of the defining requirements of the middle class lifestyle, is intended to lead to a professional career, freeing the consumer from manual labor.

Thus the primary function of “higher education” is to train young people to become office workers – people who work indoors at a computer, an inherently unhealthy artificial environment – and to condition them for a consumer lifestyle which is dependent on a disadvantaged lower class of manual laborers and service providers and the destructive global network of manufacturing and distribution. Higher education is an integral part of the vicious cycles in which dominant societies deteriorate from generation to generation.

Middle class youth are generally expected to leave home for higher education, then to migrate again, possibly multiple times, in pursuit of a professional career. The move to higher education deprives them of their roots and deprives their family and home community of their social services; henceforth they are “floaters,” generally uncommitted to any local, face-to-face community. They rarely get to know their neighbors, and become temporary members of cliques of similarly isolated peers, without the intergenerational commitment and accountability that ties real communities together.

Technologically-assisted communications – email, texting, voice phone, and social media – likewise encourage the dispersion of individuals from their families and communities of origin, by allowing an impoverished form of remote interaction that takes the place of face-to-face interaction. Without the support of extended family and a tight-knit community, urban consumers fall prey to stress disorders and mental health problems such as depression, self-medicating and enriching the multinational pharmaceutical corporations. Thus are communities fragmented and disempowered, and individuals isolated and rendered vulnerable, by education, mobility, and communications media.

How the Middle Class Destroys Natural Habitats and Ecosystems

Habitat Destruction

The media have taught urban consumers that climate change is the biggest threat to our environment. But habitat destruction, which often results in species extinction, is the primary form of ecological damage resulting from the middle class consumer lifestyle. Climate change is only one long-term form of habitat destruction – other forms are much more catastrophic in the near term.

Urban Sprawl

Urban sprawl, providing housing for the middle class and the blue-collar workers they depend on, is one of the most extreme forms of habitat destruction, in which productive ecosystems are completely destroyed and replaced by machines and impermeable surfaces which concentrate wastes and toxic materials, increasing erosion and spreading the damage to the surrounding areas.

Since cities are dependent on a network of infrastructure delivering resources from the surrounding countryside and other distant trading centers, their damage extends outward globally to infrastructure and industry located out of sight and out of mind.

Industrial Wastelands

Industrial sites such as dams, mines, commodity farms, and factories, created to provide resources for consumers, also completely destroy productive natural ecosystems, replacing them with concentrations of toxic materials.

Tesla “gigafactory” destroyed a large area of wildlife habitat in the Nevada desert:

Infrastructure Barriers

The infrastructure required to deliver resources to urban areas and facilitate communication and mobility between them results in transportation and communications corridors which become toxic wastelands and barriers to wildlife.

Toxic Innovation, Toxic Materials

The continual improvement of middle class comfort and convenience through technological innovation results in a short product life cycle and rapid obsolescence. When obsolete products are discarded, few are recycled, and many, such as batteries and electronics, add toxic materials to the environment. Innovation is incredibly wasteful.

…high-tech products are usually composed of low-quality materials–that is, cheap plastics and dyes–globally sourced from the lowest-cost provider, which may be halfway around the world. This means that even substances banned for use in the United States and Europe can reach this country via products and parts made elsewhere….They can be assembled into, say, your treadmill, which will then emit the “banned” substance as you exercise. (William McDonough & Michael Braungart, Cradle to Cradle)

One of the most revolutionary scientific inventions of the past century was disposable containers which were intended to be dumped in landfills after a single use. As time went by, these containers came to be made almost exclusively of plastics, which take centuries or even millenia to degrade. Since the 1950s, the use of plastics has accelerated, especially by the middle class, in the form of food packaging, shopping bags, clothing, storage containers, disposable water bottles, phones, toys, furniture, appliances, cars, etc.

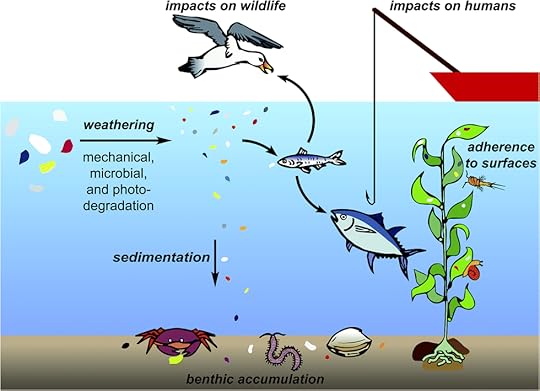

As these items age and erode, often imperceptibly, into the environment, they break down into microscopic particles or “microplastics” which spread throughout aquatic and ocean environments and are ingested by wildlife, interfering with animal and plant life cycles in unpredictable ways. The microplastics catastrophe is just beginning and may eclipse other problems we are now more concerned about.

Microplastics disperse in the aquatic environment:

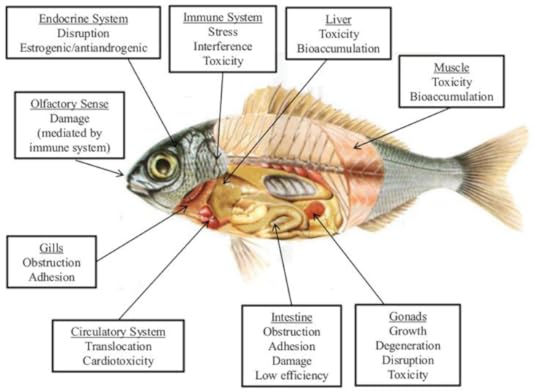

Microplastics damage aquatic life:

Toxic Mobility

Technological advances in human mobility – travel and distribution by land, water, sea, and air – ensure the rapid spread of disease and invasive species, accelerating ecosystem damage and habitat destruction worldwide. Most destructive species are spread accidentally, but many are introduced intentionally: rabbits in Australia as a source of meat, pythons in Florida and bullfrogs in the American West by irresponsible pet owners.

This map of global ship traffic shows how invasive species have been spread from continent to continent historically, as nations and empires have used technology to enrich themselves and subject native ecosystems to collateral damage:

Container ships delivering products and raw materials to American consumers also bring destructive invasive species:

Scientists estimate that technologically-enhanced human mobility has historically delivered 4,300 destructive invasive species to the U.S., ranging from Burmese pythons driving native species extinct in Florida to nutria destroying native habitat in Louisiana, from feral hogs devastating ecosystems in the South to European starlings starving native birds nationwide. The economic cost of damage by invasive species in the United States is estimated at $120 billion per year and will continue to grow as a result of technological innovation increasing human mobility.

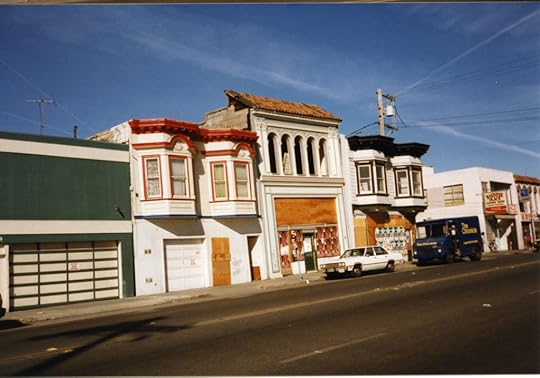

I lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for 30 years, and during that period, like most residents, I came to accept a landscape dominated by invasive plant species as “nature.” Invasive eucalyptus trees covering the hills, invasive ice plant along the coast, invasive yellow star thistle blanketing the inland meadows. It was only after I moved to southwest New Mexico, far from the coast and its ports, that I began to experience relatively intact, and far more diverse, native ecosystems.

Cheatgrass, an Old World species introduced to North America in the 19th century, has spread across most of the U.S., displacing native plants, encouraging destructive wildfires, reducing the nutrient quality of rangelands, and impoverishing native ecosystems.

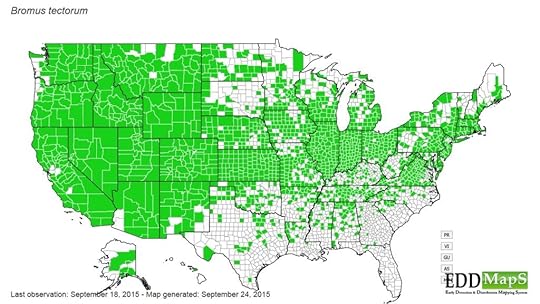

Contemporary distribution of destructive Asian cheatgrass:

Rangeland devastated by fire after cheatgrass invasion:

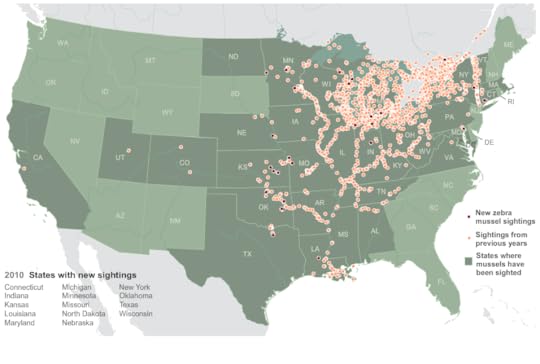

Asian zebra mussels have been spread across North America by boaters since the 1980s:

Crayfish encrusted with zebra mussels:

Energy Consumption

Technological innovation and consumers’ insatiable demand for gadgets ensures ever-accelerating consumption of energy, resulting in increasing destruction of natural habitat for mining, manufacturing, and the siting of energy production. Fossil fuels and nuclear energy require oil fields, mines, raw materials and manufacturing for plant components, industrial sites for energy plants, and disposal sites for toxic waste. Solar and wind energy require mines, raw materials and manufacturing for plant components, industrial sites for energy plants, and disposal sites for toxic waste.

This solar power plant in the Mojave Desert destroyed many square miles of wildlife habitat and continues to kill thousands of birds and pollinators:

False Hopes of the Middle Class

Politics

The centralized nation-state is made possible by a hierarchy of wealth and power. It functions primarily to enrich and empower elites, and is inherently destructive. And when the fundamental institutions of society – the ecological and social values and practices – are destructive, as described above – then political reform is like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. Middle-class society depends on the global economic and military empire maintained by the elites, and to give these up would be class suicide for either group. To paraphrase Karl Marx, politics is opium for the masses.

Green Energy and Electric Cars

So-called “green” energy is an industry like any other. Its function is not to save the planet, its function is to enable middle class consumers to continue consuming more and more energy with their devices – devices which rapidly become obsolescent and are discarded and replaced, devices whose operations add waste heat to the environment, devices which concentrate toxic materials in the environment, devices which harm society in many ways, some of which have been described above.

Electric cars are machines assembled from thousands of components whose global supply chain is untraceable, via a manufacturing process and distribution network which are energy-intensive and wasteful just like that used to produce conventional fossil-fueled cars. The function of electric cars is not to save the planet, it’s to perpetuate the already destructive mobility of middle class consumers while making billionaires even richer.

Recycling

As technological innovation accelerates, more waste is produced. The vast majority of our waste is not recycled, and when it is, recycling degrades the quality of the materials. It also requires more energy and labor on top of that required to manufacture the original products. So recycling increases our already destructive consumption of energy.

As we have noted, most recycling is actually downcycling; it reduces the quality of a material over time…the high-quality steel used in automobiles…is “recycled” by melting it down with other car parts, including copper from cables in the car, and the paint and plastic coatings…Downcycling can actually increase contamination of the biosphere. (William McDonough & Michael Braungart, Cradle to Cradle)

Space Colonization

Some tech billionaires, and many engineers and science fiction fans, believe that we should, and will, save the planet we’re destroying by abandoning it to colonize other worlds. This fantasy results from their ignorance of ecology and human social behavior. Who gets to emigrate? Middle class American consumers? Agribusiness billionaires? Mexican farm workers? ISIS militants? It’s our dysfunctional behavior that’s destroying the earth – transplanting that behavior to another world solves nothing.

Even if some colonization happens, it won’t be sustainable. A healthy environment for humans isn’t engineered from scratch, by “terraforming” another planet. It evolves with the participation of uncountable wild organisms in a terrestrial ecosystem, and humans adapt to it just like their nonhuman partners. This is the only planet we have, and it will survive with or without us.

There is some talk in science and popular culture about colonizing other planets, such as Mars or the moon….But the idea also provides rationalization for destruction, an expression of our hope that we’ll find a way to save ourselves if we trash our planet. To this speculation, we would respond: If you want the Mars experience, go to Chile and live in a typical copper mine. There are no animals, the landscape is hostile to humans, and it would be a tremendous challenge. Or, for a moonlike effect, go to the nickel mines of Ontario. (William McDonough & Michael Braungart, Cradle to Cradle)

To me, the human move to take responsibility for the living Earth is laughable – the rhetoric of the powerless. The planet takes care of us, not we of it. Our self-inflated moral imperative to guide a wayward Earth or heal our sick planet is evidence of our immense capacity for self-delusion. Rather, we need to protect us from ourselves. (Lyn Margulis, Symbiotic Planet)

How Local Providers Renew the World

Producers Not Consumers

Dominant, large-scale, centralized societies are destructive by nature. They have their own life cycle and exist primarily for the short-term benefit of the rich and powerful. They are not successfully managed or reformed for the benefit of local communities and ecosystems. The best we can do is minimize our dependence on them, transitioning from globally-dependent consumers to locally-accountable providers.

The best we can do for the earth and its people is to become successful producers and providers of basic needs for our local communities, conserving and re-using as much as possible of what we do consume, learning to do all this sustainably, and sharing what we learn so that future generations will succeed as well as us.

Local Heroes

Wherever we live, we can usually find people and organizations that are focusing their efforts on providing locally for local needs: farms, food co-ops, childcare centers, healthcare clinics, restorative justice services, churches, etc. These are the groups and people we should support and emulate, to rebuild our communities and thus take the load off the rest of the world.

Small-town farmer in New Mexico shows school kids how corn is re-seeded:

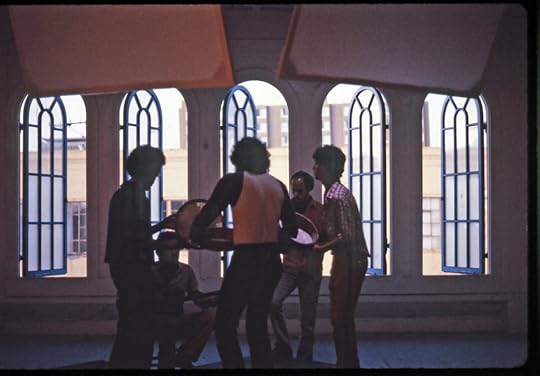

Urban youth learn to serve their community with restorative justice in Kansas City:

Traditional aboriginal skills are needed by the community to adapt to environmental crises, from crop failure to fire, flood, and war.

Students learn to process meat from an animal they killed on an indigenous skills course in Utah:

Peaceful Societies

While our dominant society destroys itself, there remain many little-known peaceful societies that offer the best hope for a sustainable future of humanity. These societies exist in the margins where they have been more or less successful at resisting the dominant society’s destructive impacts, perpetuating time-tested traditional practices and adapting to crises while our society continues to innovate and engineer itself to death. They are our best teachers.

Amish farmers in North America resist the destructive effects of technological innovation:

Unlike American middle-class consumers, the Piaroa of South America manage their natural resources communally and sustainably:

Instead of leaving their families to learn to be office workers and consumers, Ju/’hoansi children of southern Africa join their parents on foraging expeditions, learning to be providers for their community:

Like whales and other ecosystem partners, the Ifaluk of the South Pacific fish communally:

January 28, 2017

Nations Fall, Communities Rise

In childhood, our schools taught us the version of history told by the victorious conquerors: the myth of progress from savage, superstitious tribes to civilized, scientific democracies; the heroic quests of explorers, colonists and pioneers seeking freedom from oppression and a better life; the wisdom of the Founding Fathers, Lincoln freeing the slaves, modern medicine conquering disease, the democratic Allies saving the world from fascism, the environmental movement saving the planet, and science and technology making our lives safer and easier and liberating us to seek our highest potential as individuals.

Now that we’re adults, the corporate news media – romanticized as the “free press” – demand our full, uninterrupted attention to the President and his national power structure, threatening that if we turn away, we risk apocalypse. And urban consumers, dependent on the massive support systems governed by those talking heads, believe in the threat. The media predict what consumers want to hear, and consumers rejoice. Then the media report the opposite, and the shocked and saddened consumers return to the same sources, now seeking solace, enlightenment, and guidance. Consumers come to believe they have actual, important relationships – however dysfunctional – with strangers they will never meet, who are known only as talking heads on the screen.

Peaceful societies like the Amish of North America, the Piaroa of South America, the Ju/’hoansi of Africa, the Rural Thai of Southeast Asia, and the Ifaluk of the South Pacific, are burdened with none of these misapprehensions. They know their existence is always subject to disruption by external powers beyond their control, but they remain self-sufficient, independent, and vigilant, and they have learned to adapt to crises peacefully, avoiding conflict and migrating away from it when necessary.

Likewise, minorities with a history of persecution know better than to depend on kings or presidents for survival or salvation. The self-sufficiency of the North American Anabaptists is the result of generations of violent persecution in Europe. Mormons encourage self-reliance and often require their children to learn indigenous survival skills. And while the Black Panthers were seen by the centralized power structure as violent revolutionaries, the majority of their work consisted of peacefully providing social, health, and subsistence services to their local communities.

Consumers’ dependence on the centralized nation-state derives from their belief in the nation-state as a bastion of security and stability, and their fear of chaos and apocalypse should it collapse. But this is a myth perpetuated by the power structure. A reality check on history shows that the nation-state is continually destroying itself and its environment. The United States was founded in violence: the conquest of Native Americans, a revolution against the British, the establishment of borders and the defense of them. The story of its growth to a world power is the story of traumatic conversion of resilient rural subsistence communities to cities full of isolated, vulnerable consumers, and the continual, ongoing destruction of healthy natural habitat and its replacement by toxic industrial tracts and urban sprawl. Consumers remain mostly unaware of this, since they seldom leave the city and are habituated to artificial environments.

During the Third Reich and World War II, the democratic Allies allowed fascism to spread and failed to prevent the Holocaust – nor did they save the world from fascism; they increased the devastation with a world war and millions more deaths, while the Nazi regime and the Japanese empire self-destructed through hubris, militarism, and overextension. Likewise, the democratic nation-states of Western Civilization pursued a policy of imperialism leading to the Rwandan genocide, and after more than a century of “progress” and “enlightenment,” the same nation-states failed to prevent it or stop it while it was happening.

The myth of societal collapse and apocalypse stems from the misrepresentation of the European “Dark Ages,” the misnamed period after the collapse of the Roman Empire which was in reality a Golden Age of local freedom and autonomy after centuries of oppression by the imperial nation-state. Citizens of modern democratic nation-states blame the ongoing failure of Egypt, Tunisia, and Syria on religion and superstition, whereas these failed states are themselves the artificial inventions of the European democracies. The destruction, misery, and refugee crises resulting from these societal collapses demonstrate the ultimate vulnerability of urban populations and the danger of depending on centralized, hierarchical power structures.

When the citizens of Western nations begin to sense their own vulnerability and begin to fear the apocalypse, they manifest their naiveté in dysfunctional movements like libertarianism and prepping – fallacies common to even the wealthiest and most powerful citizens. These ideologies result from historical Anglo-European competitive individualism and widespread ignorance of anthropology and ecology, holistic sciences which reveal the superiority of communal societies. When centralized societies collapse, people who selfishly hoard resources and weapons to defend their families are doomed to repeat the cycles of self-destructive violence, whereas people who cooperate and peacefully nurture their local communities, adopting the lessons of the peaceful societies, are likely to thrive.

January 26, 2017

The Terra Incognita Loft: Part 5 1989-Present

Let It Come Down

It happened just after 5pm on Tuesday, October 17. John was at work downtown, and made it outside okay; he was able to walk back to Fifth Street. Leslie was working across the Bay, as was I. The engineering company I worked for was in the Berkeley Marina, on landfill. The wood-frame walls and doorways of our second floor office seemed to turn to rubber. I braced myself in a doorway as the drunken thrashing of the world around me went on for a long moment, file cabinets and bookcases tumbling across the rooms. From the moment it started, I knew my home and studio was gone, down, collapsed. It could never withstand the Big One.

I shut down my thoughts and feelings and went into full survival mode. After the shaking stopped, and we’d determined that the building was still standing and everyone was okay, I invited my co-worker, Mae, to hit the road with me. She also lived in the city and was worried sick about her partner over there. There were no cell phones or internet in those days. Regular telephone service was down. Power was out. Nothing but static on the radio.

I drove the new Tracker up the marina road toward Berkeley, where a mushroom cloud now rose thousands of feet into the sky. Ahead of us, the road had split in half, with one side of the pavement a foot lower than the other. Before time stopped, it had been rush hour, and the freeway was packed, with traffic at a standstill. Skipping the on-ramp, I took the frontage road beside the Bay toward Emeryville. It took a long time, and when we got there, the freeway ramp to San Francisco was blocked. I decided to try to get to Mike the drummer’s house in Oakland. The streets near the freeway were also jammed, so I drove my new high-clearance vehicle over the railroad tracks into back alleys behind factories, and finally made it to Mike’s place as darkness fell. His lights were on, but he told us the Bay Bridge was down and San Francisco was burning.

We watched Mike’s TV in silence as they showed the same helicopter footage over and over, of a blacked-out city lit only by raging fires in my South of Market neighborhood and in the Marina District to the north. Hours later, I was finally able to reach John at the loft by phone, and Mae connected with her partner. They were both fine, and John said the loft was damaged but, miraculously, still standing. The toilet had been shattered by falling masonry, and the power was off, but the phone was back on. My heavy stereo amplifier had been thrown off the top shelf onto the floor, but most of our stuff was still upright, including the heavy old refrigerator and the gas water heater, which we’d secured with metal straps after the earlier quake.

The Bay Bridge was indeed closed – a section of the upper roadway had collapsed – but Mae and I both needed to get home, so I took the long way around, via the Richmond Bridge, Marin County, and the Golden Gate. I dropped Mae off at her place in Noe Valley, then headed for South of Market. It was about 2am when I rolled down darkened Folsom Street, driving slow and swerving to avoid trash can fires and homeless people staggering like zombies through the rubble. I gave the darkened loft a quick check, said hi to John, grabbed some clothes and overnight stuff, and returned to stay with Mae and Xenia in their intact apartment up on the bedrock of a hill, where the electricity had come back on.

Ann, property manager for our landlord Chuck, stopped by the loft the next day, and Chuck immediately dispatched a plumber to replace the toilet. It seemed like a crazy reaction in the larger context, but crazy things were happening all over as some people wavered in denial and others frantically tried to restore business as usual. The entire Bay Area was in shock, and much of San Francisco was paralyzed. Blocks of homes had collapsed or burned, people had died in a collapse in our own neighborhood, power would be out for days. Communications were so chaotic that it was days before anyone learned that a double-decker freeway in Oakland had collapsed, crushing dozens of commuters in their cars.

I got Leslie on the phone; she was staying at her old place across the Bay. We agreed to meet at the loft on Friday. In the meantime, I called Ann and told her to get the building inspected. We couldn’t go on living there without knowing whether it was safe.

Transportation systems were down – people couldn’t get to their jobs – crews of orange-vested officials were seen everywhere, red-tagging buildings – but somehow Ann found us an engineer. I accompanied them into the bowels of the building where the main structural columns were exposed. They all had longitudinal cracks, and the rusted and broken ends of the rebar stuck out like spaghetti. The engineer didn’t really have to inspect anything, he just took a quick look and said this building was done for, totally unsafe, it would have to come down. I knew it had been unsafe long before the earthquake, before we’d even moved in. A disaster waiting to happen.

Love Among the Ruins

Leslie and I returned on Friday, and spent our last nights in the loft. A storm was coming in off the Pacific, and on Friday night I dreamed I was carried up into the eye of the storm. Saturday night I dreamed I was carried down under the earth through a tunnel. I was carried smoothly forward, past arching rock walls that glowed brighter and brighter, until I reached the epicenter of the quake, where I was overwhelmed by light and warmth and a sense of relief and peace.

On Sunday, Katie came over to help me pack. She invited Leslie and me to stay in her studio. She unfolded her sofabed, made it up with sheets and a comforter, and tucked us in. Leslie and I spent much of the night telling each other the story of our lives, but that was all that happened.

I hired a moving crew and rented a storage space in the East Bay, taking all the major appliances, believing I’d find another live-work space soon. But property owners and managers had doubled or tripled the rents on vacant spaces, taking advantage of all the displacement. And nothing was anywhere near as nice as our loft.

After the loft was red-tagged, the utilities were permanently shut off, but John and Quinn decided to camp there as long as they possibly could, thriving in danger. By contrast, Carson and Kay had recently bought a house way up on the north coast, in the pastoral, anachronistic village of Ferndale, and they invited Leslie and me up for a break from our hopeless search for housing. There, walking on the beach one afternoon, I tried to kiss her, but she turned away, saying she wasn’t ready.

FEMA finally set up a local operation to aid earthquake victims. Leslie and I waited in line in Oakland for hotel and meal vouchers. They were only valid at the cheapest chains. The only motel we could find, way up in Richmond, had stained carpets that smelled like piss, and a bed that visibly sagged in the middle. But we got our takeout voucher dinners, I bought a six pack, and we propped the window open to ease the odor in our room. Leslie asked me for a massage, and we finally found release from all the trauma and desperation in each other.

Over Thanksgiving holiday, she talked the manager of her old Mills College dorm into letting her stay there. The outside doors were locked, so I had to toss pebbles against her second-floor window at night so she could come down and let me in.

The desert property question was still floating out there, and my friend Michael from Los Angeles, another desert lover, was interested in joining me in it. In December, while I was still homeless, we drove out together to look at the two candidate properties, on opposite sides of the mountain range. He fell in love with the old man’s place at first sight, noting it would be like owning our own national park. And his mother was willing to give us a loan. So we asked the old man in Vegas if he knew anyone who could close the deal for him.

Meanwhile, the city had finally gotten around to red-tagging the loft. John and Quinn, who had been camping romantically in the ruins, there in the midst of the crippled and traumatized city, finally moved out, and Dancy boarded up the facade and put a big padlock on the street doors.

The Terra Incognita band played a couple of final gigs, one on New Year’s Eve in a Mission District loft where both Katie and Leslie were dancing in the audience, and another at a private affair in a park. Leslie and I remained homeless, but together, for months, while Michael and I were closing the deal on our desert property. Sometimes Katie let us sleep in her studio. Eventually, although she mockingly referred to her as “Teenage Barbie,” Katie got young Leslie a job as receptionist at Colossal Pictures. I moved into the three-bedroom apartment Katie shared with her friend Ken in the building above her art studio, and Leslie found a room in a house in the Mission.

Into the New World

In the late 1980s, Reagan, our criminal President, had talked our “enemy,” the Soviet Union, into embracing the rudiments of capitalism. Then in early 1989, Chinese students massed in Tiananmen Square in Beijing, demanding more freedom, but the Communist government brutally suppressed them, massacring thousands. George Bush, another conservative from a family of Nazi collaborators, had won the presidential election in 1988, and in November 1989, a few weeks after our earthquake, the Berlin Wall was opened between East and West, and its demolition begun. Naive Western Europeans and Americans celebrated, having been taught to see these events as the inevitable triumph of good over evil and proof of the moral superiority of capitalism over communism and socialism.

One afternoon in the new year of 1990, months after the quake, I found myself in our old South of Market neighborhood, and swung by the loft, which was still standing and still boarded up. I noticed two men outside Olen’s shop and pulled over. It was Olen and his son. Olen had had a stroke and couldn’t speak, but he recognized me and smiled. The son explained that they were trying to retrieve a car from inside our building.

The lower floor of the loft had a dogleg garage extension onto Shipley alley. We managed to raise the rollup door, but Olen’s old VW Beetle, which didn’t run, was down inside, in the dark, at the bottom of a ramp. Together, the three of us labored and slowly pushed it up and out onto the street. Olen beamed. Back in the day, he’d been the King of Fifth Street. Now, only a few months later, he was a ravaged old man, barely functioning, collateral damage of the earthquake. It was the last time I saw him, and the last time I saw the loft standing. Chuck’s three condemned buildings disappeared as if they’d never existed, to be replaced by a sunken dirt parking lot, which remains to this day.

Leslie and I drifted apart. We stayed friends, but she moved back to Chicago, where she’d grown up. I attended a two-week primitive skills class in the wilderness of Utah where I learned the lifeways of the Indians who lived in my beloved desert and left the rock art Katie and I had studied, and in 1991, four years after the last Pow-Wow, I organized another Pow-Wow at Philippe and Cindy’s field station, this time starring the lead instructor from my Utah class, and adding new friends to the old crowd from both Northern and Southern California.

John and Quinn got married and spent a long honeymoon in Spain and Italy. Back in the Bay Area, they started a family and later moved to Ireland, where John joined a theater group and Quinn did archaeology. Recently, they returned to the Bay Area.

Two years after the quake, I moved into a small house in Oakland with a carport where I could store the appliances from the loft, so I retrieved them and all my other stuff from storage. Part of me was still hoping to get another industrial space that I could build out, to create another dream studio and home.

In the Oakland house, I reassembled my recording studio and reviewed my decade-long musical career. The last iteration of the Terra Incognita band had been the most musically coherent and successful, but in some ways the most frustrating. The lead guitarist’s work, and the long solos by him and the other players, had constantly grated on my traditional-music sensibilities, and we’d never found a backing vocalist that suited me, but all the players had been so accommodating and supportive of me and my songs that I’d never had the heart to challenge or replace them. Instead, in another of my typical creative flip-flops, I abandoned the big band sound and went acoustic, resurrecting my banjo, ordering and learning to play my own custom-made West African drums, writing more desert-inspired songs, and adopting a deep-tribal sound explicitly inspired by archaic Nigerian and Appalachian styles.

But my passion for the desert was quickly taking over. We’d finally acquired our land and were starting to do habitat restoration work. I decided to just move out there and live on the land – working with desert scientists, delving deep into the ecology and archaeology, testing my new aboriginal skills in the middle of the wilderness – so I finally sold off all the old loft appliances. It was a hard time and place for selling – even the Wedgewood range went cheap. I quit my day job at the Berkeley engineering firm, for the last time, and it went out of business within a few years.

Loft of Dreams

In September 1993, four years after the quake, I was back in the Bay Area, and we relived the golden years of the loft in a Terra Incognita reunion. Laurie flew out from Minneapolis, and Katie, Laurie, John, Quinn, and I took the ferry to Angel Island where we picnicked and made music together at The Bell.

After the reunion, Katie moved back to Los Angeles, and I visited her there. In Minneapolis, Laurie and Marc had divorced. He’d pursued a career in poetry, and later took his own life, but Laurie had gone on to become an acclaimed creator of public art in the Twin Cities, tackling difficult issues like domestic violence and suicide.

I moved into the Oakland house of Mike the drummer from the TI band, and we started a new group, Wickiup, with Jane, a Cherokee singer and multi-instrumentalist, to try out my idea of a deep-tribal sound that we called Acid Country or Native American Country Gospel. Hotel Utah, a legendary bar and nightclub in the old loft neighborhood of San Francisco, was now managed by Guy, the lead bass player from the short-lived 1988 version of Terra Incognita. There, Wickiup debuted “Precious Time,” the song about Leslie, the loft, and the quake that I’d written while we were still homeless in early 1990. We performed and attracted a loyal audience for two years before I got tired of that style and flip-flopped again, inspired by the now-popular grunge movement from Seattle.

I moved to Los Angeles in 1995, and Leslie flew out from Chicago two years in a row to join me in camping trips to the desert. I started making desert-inspired pastels again, and experimented with Asian-inspired ink brush art. And gradually, after years of unemployment and poverty, I reinvented myself as an information architect in the Dotcom Boom, and moved back to the Bay Area for a high-pressure new career as a “creative professional.”

When I founded the loft in 1981, my young peers and I had been part of a generation that was angry and skeptical, disillusioned with government, politics, industry, media, capitalism and consumerism. Our opposition to the established system and mainstream culture was the source of our hope for the future and the inspiration for our creativity. But now I was working with creative young people who were making tons of money working for corporate clients. They fervently believed that technology and capitalism would bring about Heaven on Earth: a democratic, globally networked playground filled with sparkling, kaleidoscopic screens, friendly robots and rocket cars. I would ride the wave, but I had seen too much to share that dream.

In 1997, eight years after the quake, I started dreaming about the Terra Incognita loft. It’s as if it continued to exist in a parallel universe – actually, any number of parallel universes, because the city around it continues to change, modernizing in different ways each time, and the loft itself is different in every dream. Sometimes it’s the same space, and sometimes it’s bigger, with extensions, or just with more monumental dimensions. Most of the time, strangers are living there and transforming it in cool and intriguing ways. But sometimes, it’s the same, and some of the old roommates have returned. I still have these dreams and I expect I always will.

I also reconnected with Tiare in 1997 – by phone, mail, and email – but we have yet to meet face to face. She’s happily married and living in the Los Angeles area, and still making art. And much later, after moving to New Mexico, I reconnected with Gary, Mark, and Scott from the original Terra Incognita band. Mark continues to experiment with his fiddle, Scott’s a successful actor, and Gary paints, having taught art to seniors until his retirement this month.

I opened the San Francisco office of my design business in North Beach in 1999, and one day while grabbing a sandwich at Molinari’s deli across the street, I glimpsed someone who looked like Popeye, the dashing but mentally ill older man who’d lived in the flophouse around the corner from the loft, parading around the neighborhood in flamboyant costumes. Like Popeye, the man I saw in North Beach looked clean cut and physically fit. He wore a white shirt and dress slacks, and carried grocery bags. When I described him to my young assistant, she said he was a widely-known, independently wealthy San Francisco personality that she and her husband had spoken with several times.

The ultimate triumph of the loft was Jon and Laurie’s marriage. Jon had landed a prestigious editing job in Minneapolis in the mid-1990s, and since Laurie was already established there, they started hanging out together, and I was eventually privileged to serve at the wedding of these two friends who had first met at Terra Incognita 16 years earlier. And Jon has resumed the career in performance art that he and I first dabbled in at the loft in 1981.

I love and miss all my talented and courageous friends from the nine years of the Terra Incognita loft. As artists, we needed a place that was ours to experiment with, outside the constraints of society. A place that was illegal and dangerous, forcing us to stay alert and learn how to keep from falling off the sharp edge of art, love, sanity, even life itself, that we so often balanced precariously on. Terra Incognita was that place, and it served us better than anyone could ever have dreamed, and in our dreams and memories it will never die.

January 21, 2017

The Terra Incognita Loft: Part 4 1987-1989

Pow-Wow ’87

With Laurie’s departure at the end of summer 1987, the loft population was back to three. I’d been without an art studio for almost three years, and Katie’s projects had been wedged into a corner of the guest room, so we took over Laurie’s room, and on the nights we didn’t have rehearsal or a gig, we had art nights.

My pastels were now all about the desert: forms I’d seen or dreamed, stylized like Native American rock art. Back in 1986, after hearing from Chris, the biology student, that the University of California had established an ecological field station near our desert cave, we’d driven over there and met the new directors, Philippe and Cindy. The four of us clicked from the start and became good friends. They began to turn us on to the ecology and prehistory of our favorite place, the ongoing research and the people who were conducting it. Our heads were exploding with this new universe of images and ideas for our art and music. The more we learned, the more we wanted to know.

Our loft technology was also advancing. Back in 1985, we’d acquired a massive, used IBM Selectric electronic typewriter to produce lyric sheets, songbooks, and promotional correspondence for the band. But after the Pow-Wow in 1986, we’d replaced it with an Apple Macintosh computer and dot matrix printer. John had already set up a workstation in the hallway with his MS-DOS computer, so we added the Mac and began experimenting with graphics for posters and databases for our band mailing list.

John’s latest project was a brilliant Spiderman web of rope he strung across his room below the ceiling, from his sleeping loft to the opposite wall, so he could roll out of bed into it and crawl around up there. We knew he was airborne from the creaking sound of the ropes.

In the fall, despite our sadness over the loss of our roommate, the momentum of our activities kept intensifying. I’d been corresponding with Jon about the next art/science Pow-Wow, and with Philippe and Cindy about holding it on their desert field station, at the ranch house where we’d met Chris in December 1985. Katie had initially been skeptical about our Pow-Wows, thinking they’d be too nerdy and uncool, but now she was fully on board, along with our large community of artist friends in Los Angeles, for whom the desert was only a short drive away.

Philippe and Cindy put Pow-Wow ’87 on their calendar for late October, and I prepared a two-page invitation on our Mac and sent it out to dozens of people on our mailing list. As both artists and scientists eagerly signed up, I compiled text and images from dozens of references Katie and I had acquired during our desert researches and produced a 200-page Reader on this environment most attendees would be experiencing for the first time, and its prehistoric culture. As I had with previous projects, I printed and bound the Reader surreptitiously at my day job, after hours, and mailed copies to all the Pow-Wow registrants on my own dime. Many of them would read it out loud during their journeys to the desert, preparing questions and special projects to share with others.

Meanwhile, Katie was tirelessly badgering record companies with our recent recordings, and our friends Norman and Benjamin had scored us a gig headlining a Friday night show at the Knitting Factory in New York City, based on the Village Voice review of our track on the Potatoes album. This was our biggest opportunity ever – the Knitting Factory was the leading showcase for new and experimental music in the U.S.

The first desert Pow-Wow was a massive group effort. Jon flew from New York to Las Vegas, where he met John and Ellen from the Bay Area and they all rented a car to drive to the remote field station. Michael and others from Los Angeles carpooled and hauled loads of firewood, food, and beverages. Katie and I drove down from San Francisco on Wednesday and stayed at our cave the first night, to be joined by other Bay Area friends at the ranch house on Friday afternoon. Gear was unloaded and a cooking assembly line was set up in the kitchen, supervised by Katie and our friend Tia, a professional chef and caterer, while people erected tents amid the cactus and scrub outside.