Max Carmichael's Blog, page 28

September 2, 2019

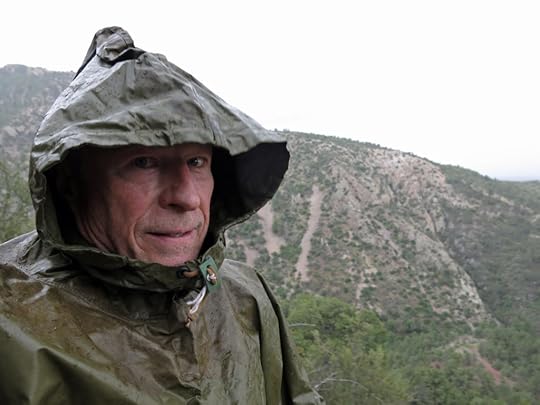

Top of the Burned World

Wild Raspberries

In the third week of recovering from my latest foot problem, I was in a real quandary picking a big weekend hike. For a gradual recovery, I felt I still needed to avoid steep grades and keep the cumulative elevation gain under 2,000 feet. But last weekend’s hike had been almost 8 miles, so I figured I could do 10 or more this weekend.

But the logical choice, an area close to town, had been taken over by mountain bikers for a big annual race. And the areas over on the west side of the federal wilderness were just too steep.

One hike I’d considered in the past was to follow the crest trail of the Black Range north to one of the range’s highest peaks – about a five mile one-way with 2,000′ elevation gain. But I knew there was a fire lookout on top, and I assumed there was a forest road to the lookout. I believed this would be a popular trail, and I was leery of running into vehicles and some kind of a crowd up there.

In addition, we’d been having monsoon storms almost daily. That ridge had been mostly cleared of forest by the catastrophic wildfire in 2013, so I would be spending most of the day totally exposed. Without cloud cover it would be hot, but in a storm I’d run a real risk of being struck by lightning.

After deliberating a while, I decided to chance it. It was an hour drive from home, and maybe by the time I got there, the weather might be more predictable. There was another trail option in the same area if I had to give up the crest hike.

The highway hairpins its way to a pass above 8,000′, where there’s a scenic overlook and the crest trailhead. The sky was mostly clear when I arrived, with just a few little scattered cumulus clouds to the northwest. The temperature at that elevation was still in the 70s at 11am, but radiant heating in the thin air was pretty fierce, and I was sweating heavily within the first few hundred yards.

I ran into a pair of mountain bikers coming out, half a mile up the trail. Great – was this a harbinger of the traffic ahead?

I’d walked the first mile of this trail last year, so I knew it traversed the heart of the burn area. The slopes to north and south had been scorched to moonscape in large swaths, and although gambel oak and other scrub was filling in, there were clear views to east and west from this north-south trending ridge. And the views went on forever, into a haze more than a hundred miles away.

After a snowy winter, a hot spring, and weeks of monsoon rains, the wildflowers were spectacular. Birds were busy everywhere, some of them unknown to me. Whereas wild raspberries in the canyons had already mostly fallen or been eaten, there was a huge crop ripening up here, and by the end of the hike I’d eaten nearly a pint.

It turned out that the departing mountain bikers had only ridden the first mile or so of the trail, and they were the only humans I encountered throughout the long day. The grade of the trail was so steady that I had a hard time believing it climbed 2,000′ in 5 miles. It seemed the perfect hike for this stage in my recovery.

Hidden Spring

The peak is topped by a large grassy plateau at a little over 10,000′. And to my surprise, there was no road! The summit complex, consisting of tower and two cabins, was vacant. They must helicopter in materials, supplies, and some of their crews. And the lookout tower is tiny and would only accommodate one person in short shifts. I wondered if they even use it during a normal season.

After checking out the cabins and climbing to just below the boarded-up lookout for some 360 degree views of my world, I returned back down the trail. Just below the summit there was a junction with the northward continuation of the crest trail, and the sign mentioned a spring. I’d had such a wonderful experience with a mountaintop spring over on the west side, I figured I’d explore this one, if it wasn’t too far.

The trail took me down through lush, unburned forest to a small meadow where a signed spur trail led off to the spring. The sign said 1/2 mile to the spring, but the lettering was so faint I didn’t make it out until after I’d unsuccessfully tried to reach it.

The trail to the spring was almost invisible, but there were periodic cairns that enabled me to keep going. The cairns led down a rough slope with many snags and fallen trunks, a deeply eroded surface with a lot of loose rock and bare dirt. There were some interesting rocks, but after taking me several hundred feet down the mountainside, the cairns led into a dense, dark aspen thicket on an even steeper slope, and I gave up the search. I just didn’t want to end up going another half mile and a few more hundred feet farther down, that I’d then have to climb back out of.

Flowers & Fungi

Most of these flowers – but not all – were familiar to me from other parts of these mountains. But for sheer numbers of wildflowers, this crest trail has them all beat!

Cat Calls

Most of the upper forest on the peak was defended from the wildfire, so while hiking this upper trail, you only get glimpses of the landscape from between old-growth fir and spruce.

But the glimpses you do get are stunning – you can really tell you’re a mile above the rest of the world. The mountainside is so steep it’s almost vertiginous.

Clouds had gathered during my hike, and much of the peak was shaded by forest anyway. Temperatures had stayed mild all day, and there was always a breeze up here on top of the world. At some point on the east slope of the peak, walking through dappled shade with a gentle wind rustling the aspen, I suddenly felt my chest filling with euphoria. I remembered feeling that way a couple days earlier, when hiking a much smaller peak in a similar situation, being up above the world in clean air, looking down across a vast wild landscape. I’m used to feeling happy in nature, but this was different – I was actually high, in both senses of the word. I wondered if it was because now, after the fire had cleared most of the trees out of the way, I finally had long sightlines just like I have in my beloved desert.

The feeling stayed with me all the way down. It felt like there’d been a sea change in the way I experienced nature. I had no adequate explanation – it was just there. Will it happen again?

Traversing the head of the last canyon on the west side of the crest, I heard a strange, haunting repeated cry from the patchily burned forest low on the opposite slope. At first I thought it was a bird, but the longer it continued, the more it sounded like a cat – probably a bobcat, either in heat or in distress. I heard it for nearly a half hour, until I rounded a shoulder of the ridge and passed out of hearing.

August 25, 2019

Monsoon Canyon

I hadn’t been able to do a serious hike for the past three weeks, due to problems in both feet, a knee and a shin. So I needed a recovery hike on a well-maintained trail without any long, steep grades. This canyon, less than an hour from home and between 7,000′ and 9,000′ elevation, fit the bill.

While I was out of commission, our monsoon had been delivering some good rain. The flowers were outrageous, there were still red raspberries available, and a huge crop of rose hips would be ripe in a few more weeks.

My lower body felt so good that when I got to the steep part near the end of the trail, I wanted to keep going. But I’d already hiked farther than I’d planned – the round-trip would be almost 8 miles and over 1300′ – so I decided not to take any chances.

In addition to the wildlife I got pictures of, I saw two garter snakes and a bridled titmouse – first ever in the wild! And in the lower part of the canyon, I heard an invisible owl calling – in the middle of the afternoon!

The Arizona Sister is a big butterfly – same size as a swallowtail – and the dark band of color along the front of the wings is iridescent.

August 9, 2019

A Life in Business Cards

We all collect business cards. A few of them are creative. Most of them are boring.

Here’s a random sample of cards from the 1970s through the 2000s – including a few of my own – that suggest some of the eclectic worlds my life path has intersected with, and the differing ways in which people from those worlds introduce themselves to strangers.

Business Cards

We all collect business cards. A few of them are creative. Most of them are boring.

Here’s a random sample of cards from the 1970s through the 2000s – including a few of my own – that suggest some of the eclectic worlds my life path has intersected with, and the differing ways in which people from those worlds introduce themselves to strangers.

August 5, 2019

Canyon of Chaos

I was still bored with the hikes near home, and I kept dreaming about the canyon hike beyond the state line to the west, that climbed 4,000′ from high desert to alpine habitat atop the Sky Island. I’d expected that to be a good warm-weather hike, with its shady canopy in the canyon bottom and cooler temps during the climb to higher elevations.

On my previous visit the creek had been impassable where the road to the trailhead crossed it out on the bajada, a mile from the actual mouth of the canyon. But that was in early spring with snow still melting on the peaks, and I assumed the creek would be lower now, and I’d be able to drive to the upper part of the road, where I knew there were some good campsites at the mouth of the canyon. I figured that if I left home in mid-afternoon, I’d be making camp around sundown in cooler temps, and could get an early start the next morning to beat the heat.

I could see a lot of weather ahead during the two-hour drive west. And on the final approach, driving over a spectacular pass between mountain ranges, I surprised two roadrunners crossing the highway. At the state prison, I drove around the fence and through the staff housing like before, but on the west side, the gate to the Forest Service road was padlocked.

I returned to the prison entrance and parked outside the Administration building, where the Forest Service website had said to ask for a key. But it was closed on Saturday, so I tried the Visitation building across the street. Inside, I had to walk through a metal detector before reaching a window. Two uniformed ladies behind it seemed surprised to see me. They had no idea about the creek, the road, or the gate I was talking about, but one of them asked me if I had noticed the newly constructed gate beside the highway just before the prison entrance. She said they had bulldozed a new road there because of problems with vandals along the old road.

I found the new gate and turned onto the new road, which was just a poorly graded gash across the bajada. There were cattle all over the road, and I had to threaten them by revving my engine to get them to move away. I could see this new road would quickly become impassable after a little monsoon erosion, and I wondered if the Forest Service even knew that their trailheads were at risk of becoming inaccessible over here.

Up and down, around and around, over the exposed rocks and through the rough-dried mud of this heavily grazed, mesquite-riddled rangeland, I finally got to the National Forest boundary. A redtail hawk soared overhead. When I reached the creek crossing, I could hear the creek roaring off to my left, but the roadway, which followed an abandoned dry creek bed above the active one, looked okay at first. But as I walked ahead to be sure, I came upon a boulder pile, the remains of heavy flash-flood erosion, that would require more than twice the ground clearance I have in my vehicle. In fact, I didn’t think any vehicle, apart from maybe a military Humvee, would be able to cross here.

Clouds were threatening rain, and there was no place to camp in the mesquite thicket along the lower part of the road. I explored off the road a bit, hoping to find a clearing I could use, but there was nothing doing. I did find some prehistoric bedrock mortars from the Old Ones, which was encouraging, but the ground was thick with ants. I decided on Plan B, a cheap motel in the nearest town, which would enable me to explore the big valley south of the mountain range.

The road down the valley starts out in some very lonely ranching country. But the first thing I encountered was a large elementary school, seemingly in the middle of nowhere, and the second thing I encountered was a beautiful pronghorn antelope, grazing on the shoulder of the road. My passing vehicle didn’t bother it at all.

I had mixed feelings about my decision after finding that the last third of the road to town was crossed by sharp seams every dozen feet, which made the drive pretty violent – BAM, BAM, BAM for at least ten miles. The valley there is heavily populated, and I couldn’t understand how people live with a road like this.

But after a steak dinner and a good night’s sleep, I found the road easier to take when returning north the next day. One highlight of this road, if you could call it that, is the NatureSweet tomato complex in the middle of the valley, more than two miles of continuous greenhouse, possibly the largest such facility in the world. I didn’t know there was that much glass on earth!

Back at the creek crossing, I was surprised to find two vehicles already parked. I’d wrongly figured that the heat would keep people away this time of year. I pulled off at the only remaining spot and prepared for my all-day hike. It was only 9am but it was already pretty warm, and I had a mile of open country to cross before reaching the mouth of the canyon with its shady canopy.

Where the road enters the canyon, it’s deeply eroded – basically just a long pile of boulders – but I could see that someone had driven some kind of 4wd vehicle over it recently, having crossed the creek, where they would’ve needed at least 18″ ground clearance. What the hell had they been driving? Rounding a bend, I surprised a couple of white-tailed deer, the buck wearing a tall, feather-duster tail like one I’d seen last year near home.

I reached the clearing beside the creek where the old road turns away to climb toward the ridge trailhead. I could see the white and green sections of 6″ diameter PVC pipe across the creek, propped up on stands, which used to supply water for the prison. I heard a voice and noticed there was an old guy sitting in a folding chair, reading a book, back in the shade of the clearing. Since I’d never actually taken the canyon trail, I asked him if the road led to the canyon trailhead. He didn’t seem to know what I was talking about, but he recommended hiking to the waterfall, which I had read about. I knew the waterfall turnoff was only a mile up the canyon, but he claimed it was “a long way” and easy to miss.

What the old guy referred to is a small waterfall in a side drainage, a mile from the trailhead, which has been enhanced by a metal catwalk like the more famous Catwalk near my home. It seems to be the most popular destination in this canyon, but I had little interest in it this time around – my goal was the high country, five miles away and 4,000′ above.

I reached the trailhead for the ridge trail I’d hiked before, and found largely abandoned. That abandoned trail has a nice Forest Service sign, but the creek trail, which has a number and a detailed description on the Forest Service website, has no sign, and no formal trailhead. What, me worry? I was blithely strolling up the old road in the sun-dappled shade of the canopy, looking forward to my canyon morning, when I suddenly spotted a black bear crossing the road about 60 feet ahead of me. I talked to the bear to make sure it knew about me, but it ignored me completely and plodded on into the streamside undergrowth. After a while I continued on up the road, but it soon ended in a deep ravine that had been cut by erosion out of the steep western slope of the canyon.

This is probably a good point to admit that I was poorly informed about this hike in general. I’d read the Forest Service website trail description, I’d studied the trail map available on the Arizona hiking website, and I’d read two or three fairly recent trip logs. It seemed like a very straightforward trail – it just followed the creek a few miles then climbed a section of switchbacks which continued to the crest – so I hadn’t brought the map with me.

What I hadn’t paid enough attention to was the dates of the recent hikes on this trail. It turned out they had all been done prior to the 2017 wildfire on the crest of the range. Because since the fire, as I began to discover a mile or so up the trail, the entire canyon bottom had been filled with flood debris – an unfathomable tonnage of boulders, tree trunks, and smashed, twisted, and broken piping from the prison’s ambitious but long-abandoned water system. Whenever I ventured away from the canyon bottom, I could see floodwaters had reached as high as 50′ above the current streambed, lodging debris high in trees far up the slopes. It was hard to imagine the Biblical scale of those floods. Had they occurred during spring rains on top of snowmelt, or during violent monsoon storms? In any event, there was little left of the old road – which had to be the trail, since there was clearly no other way up the canyon – and I soon got sidetracked and found myself lost, crisscrossing the chaos of giant piles of boulders and logs, with the stream raging somewhere below.

I wasted more than an hour on this, meanwhile crossing and re-crossing the stream on boulder steppingstones. Somewhere in there I noticed a faded pink ribbon on a branch, which sometimes indicates a trail. I followed two or three of these ribbons but they just led me to dead ends deeper in the maze.

Finally from amid my latest pile of debris I spotted what looked like a continuation of the old road, high on the opposite bank above the stream, so I fought my way over there and scrambled up. Sure enough, it was an intact section of the old road. I followed it for a few hundred yards, encountering an abandoned cabin I’d read about in one of those trip logs. And shortly afterwards, the road ended again on the brink of monumental chaos – what appeared to be a giant glacial moraine that had recently engulfed and killed an entire riparian forest in some catastrophic debris flow of unimaginable scale.

I just stood there in awe, shaking my head, wondering what the living hell I’d gotten myself into. I was already battered and drenched with sweat from my morning’s exertions. It was almost noon.

Choked by the chaos of debris, the dead forest still stood, its brown foliage indicating that this catastrophe had occurred recently, during the current growing season. I assumed from the surrounding landscape that this was the junction of Grant and Post Creeks, and I vaguely remembered – in error, as it turned out – that the trail turned east here to ascend Grant Creek, leaving Post Creek to continue due north by itself. But how was I to find any evidence of the trail, which had to be buried somewhere dozens of feet beneath this vast field of boulders and logs, out of which crushed and twisted sections of steel and PVC pipe protruded like veins from a severed limb?

Already on the point of giving up, I managed to climb across the moraine with less trouble than I expected. It was perhaps a hundred yards across at the junction. I searched for evidence of the trail on the other side, but there was none. So I made my way up the moraine until I came to some shade near the outer edge. There I had lunch and glumly studied the shadows in the forest below. I could see more piping over there in the trees – maybe I’d find the trail over there?

Sure enough, no sooner had I entered the forest than I spotted another pink ribbon on a branch. It seemed to indicate some sort of primitive trail that in most places was simply a steep erosion channel through the forest. Alongside it, big clumps of debris had been caught up in the trees during the massive floods. I was surrounded by the ghosts of apocalypse.

More ribbons led me forward, until this “trail” finally rejoined the moraine and Grant Creek beyond it, out in the open again. The last pink ribbon seemed to indicate that I should cross the creek here, to find a trail continuation on the other side. But it meant climbing back over the boulder pile. And midway there, I found another monument to the power of the massive floods: a trio of giant Ponderosa pines, still living, with the trunk of an equally huge pine lodged across them to create an accidental dam.

With no more pink ribbons in view on the opposite bank of the creek – nothing but another forested slope too steep to climb – I clambered back on top of the seemingly endless moraine. And from there, beyond a northward curve of the canyon, I spotted something completely unexpected, that none of the maps, trail descriptions or trip logs had mentioned: a towering, spectacular waterfall.

As impressed as I was by the waterfall, it was also disheartening. It blocked the canyon even more permanently than the debris pile below, so there was clearly something wrong with my belief that the trail led up this canyon to a set of switchbacks. Unless I could find those switchbacks somewhere at the base of the slopes to either side of the waterfall.

But after another hour or so of exploring and scrambling up the very steep slopes on what turned out to be game trails, I realized I was beaten. It wasn’t even that late in the day, but without a map, I had no idea where else to look for the trail. This upper part of the mountainside consists primarily of cliffs, so there wasn’t even an obvious place to start looking.

Clambering perilously back over the moraine, I found the pink-ribboned trail that had brought me there, and decided to follow it back down the canyon as far as possible. It quickly led me back out onto the lower part of the moraine, at the junction of creeks, and from there I crossed and climbed up onto the orphaned segment of the old road.

My way back down the canyon was easier, though, because now I knew that the old road had stuck to the west side in this upper stretch, and when the road itself was eroded away, I carefully traversed the steep, loose dirt of the slope high above the raging creek until the road reappeared ahead.

Halfway down the canyon, I heard thunder behind me, and looked up to see a mass of dark clouds above the ridge to the west. I figured I was okay as long as it stayed over there. But if the storm drifted over the head of my canyon, there could be trouble. A flash flood would block my way back to my vehicle, at least until it had run out. In the worst case, there could be another apocalyptic reshuffling of the canyon, with me in it.

When I finally emerged from the mouth of the canyon, I looked back to see that rain had indeed engulfed the head of Grant Creek. I had a mile to go to the creek crossing, and the flood waters from that rain would surely beat me there. I was likely to get cut off!

My chronic foot injury doesn’t allow me to run a mile, so I just kept striding down the old road. About halfway to the crossing the road rose above the bajada and I heard a roaring, like a locomotive, off in the direction of the creek. It was in flood! What would I find at the crossing?

But when I got there, the creek looked the same as it had in the morning, 7 hours ago. I crossed easily, and from my vehicle, I looked back to see that the storm over the mountains had already cleared. I realized that although my original plan of climbing to the crest had failed, I had discovered a beautiful, unexpected waterfall, and I’d been lucky to escape a storm. My body was thrashed from all that climbing over logs and boulders, but maybe it had been worth it after all.

In recent years, I’ve hiked many burn scars high up on peaks and ridges. On this trip, I was challenged to experience the damage caused by erosion and flooding down below, after the alpine forests that hold the mountains together are burned off of the heights. I have the feeling that my education is just beginning…

As I’ve said over and over, the monsoon is the best season of the year here in the Southwest, and the sky rewarded me with an endless pageant on the drive home. The icing on the cake was my discovery that we’d had a good storm there while I was gone.

A quick check of the trail map on the Arizona hiking website revealed that despite my delusion, the actual trail doesn’t turn east up the Grant Creek canyon. It continues due north along Post Creek, and the switchbacks start about halfway up, on the east bank about a mile beyond the junction. Since most of the erosional damage seems to have occurred on Grant Creek, I might well have been able to relocate the trail and proceed to the crest if I’d simply brought a map with me. Maybe next time…

July 29, 2019

First Steps in the First Wilderness Part 6: Late July

When I started this familiar hike in late morning, there was not a cloud in the sky over the entire mountain range. By the time I reached the peak in mid-afternoon, cumulus clouds were massing over the center of the range. As I returned down the canyon, a dark ceiling hung overhead, thunder was rolling behind me, and a light rain was falling. And as I drove toward home in early evening, most of the clouds had dispersed.

The canyon bottom was even more of a jungle than before. I wondered how thick it can get by the end of monsoon season!

July 25, 2019

Protected: Canyon Tuesday

This content is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

July 15, 2019

Be Careful What You Wish For!

Five years ago, before I was crippled by joint problems, my cardio routine consisted of one or two 4-mile weekday hikes within 15 minutes of home, plus a 5-7 mile hike a half hour away on the weekend. But when I finally began recovering, it inspired me so much that I became a lot more ambitious, and it’s getting harder and harder to find hikes that challenge me – and don’t bore me.

So I’m driving farther now, even for the midweek hikes. Every other weekend I’ll drive an hour or two away, hoping to get into some canyons and ridges with exposed rock. Our lower-elevation pinyon-juniper-oak forests tend to get monotonous, as do the mixed-conifer-and-Gambel-oak forests at higher elevation.

But last weekend I’d done one of the farther hikes, so this weekend I was condemned to something closer to home. I decided to try a route I’d never done before, using part of the famous national trail system to get to the highest peak near town. I’d climbed that peak many times from the opposite direction, but the topo map for this alternate route showed numerous ups and downs that would give me even more cumulative elevation gain. And the trail would take me across the north face of the Twin Sisters, a dramatic formation on our local skyline.

Our monsoon still hadn’t really kicked in, but by hiking in mountains I had managed to get into some rain in two of my last three hikes. Today, however, the forecast gave only 20% chance of rain, which is generally hopeless, and there were only a few sparse clouds over the mountains and clear skies over open country. It was supposed to be a little cooler, with a high of 89, but by the time I found the trailhead it was sweltering. I passed several people on their way out, having sensibly started much earlier in the cool of the morning.

But I had an attitude about hiking in heat. Thirty years ago I’d accompanied wildlife biologists on field trips in the Mojave Desert, and in the middle of summer, with temperatures 10 degrees hotter than it ever gets here in New Mexico, we would start a hike at 11am and climb rugged mountains off-trail all day in full sun, only returning to camp after sunset. And just a few years ago I did a backpacking trip there involving strenuous climbing, in temperatures pushing 100 degrees. So I viewed our local heat as no impediment at all.

I was hoping for some shade, though. I’d studied Google satellite view and it looked like maybe two-thirds of the hike would be in pine forest, with maybe some sparse cover throughout the remainder. But the reality was disappointing.

A large proportion of the national trail turned out to utilize old forest roads, so there was a wide corridor where trees had been cleared, hence no shade. And the middle section of the trail traversed a rolling plateau with my most hated surface: embedded volcanic projectiles, roughly rounded and pitted rocks ranging from tennis ball to bowling ball size, embedded in hard clay. This is a common feature of our local mountains that I’ve learned to avoid whenever possible. The rocks can’t be cleared by trail workers, so all they do is remove the vegetation around them, and walking over this unevenly cobbled surface is slow, perilous, and hell on your feet and leg joints.

The trail began with a steep climb, and the lack of shade meant that I was drenched with sweat within a few minutes past the trailhead. Crossing the plateau was a true ordeal. I hadn’t been able to figure out how long this trail was before starting it – I hoped to reach the 9,000′ peak, but there was a possibility it might be too far for a day hike. And the first third of the trail turned out to be twice as long as expected. I was not optimistic, but I wanted to at least reach the Twin Sisters, about two-thirds of the way to the peak.

There was a small patch of dark clouds hanging over the peak, so I silently let myself hope for some weather. And by the time I was traversing the north face of the Sisters, clouds were providing periodic shade over the trail, and I started praying out loud. “Clouds!” I shouted. “Storm! Lightning! Thunder! Rain! Bring it on!”

Past the Sisters, the trail finally entered a continuous forest of tall pines that provided blessed shade. And thunder started cracking and rolling up ahead of me, on the far side of the mountains. I dug some snacks out of my pack for lunch and began hiking faster, eating enroute.

This forested part of the trail traversed the west side of a long, narrow canyon to the drainage at its head, then turned out the east side of the canyon to a switchback that began climbing to the peak. It was getting close to the time when I should turn back, in order to get back to town at a reasonable hour, but I was tantalizingly close to my original goal, the dark clouds moving over were energizing me, and I was moving fast. Just before I reached the point on the trail where I had turned back, months ago, coming from the other direction, little drops of rain started to fall. My prayers had been answered!

It was only a sparse rain at first, and most of the time these little rains are short-lived, so I kept climbing without donning my poncho. But within minutes it was raining harder and I suited up. I was climbing fast, and I was halfway up the switchbacks to the peak when a downpour began rattling the hood of my heavy rubberized poncho like machine gun fire. The lightning and thunder were getting close, with long echoes of thunder rolling out in all directions from the clouds directly above. We’re often sternly warned against hiking in thunderstorms, but I figured my rubberized poncho would protect me from lightning strikes. The rain was so loud on the poncho’s hood that I looked more closely around me, and suddenly realized there was hail mixed with the rain.

I had a vague idea of where I was, and had started to hope I might actually reach the peak, regardless of how late it might make my return. I was getting so close! But the storm had moved directly over me. The wind whipped the hail against me from all sides. My feet were drenched in my supposedly water-resistant Goretex boots, and I would have to hike all the way back in them. Even my shirt felt soaking wet, inside my poncho.

Being inside the storm was so exhilarating that I kept climbing, onto the last switchback before the peak. Then I noticed that the trail ahead had turned into a stream, a flood pouring down the mountain toward me. Hail was piling up around the bases of the rocks and pines. The lightning and thunder were continuous, all around. I finally gave up and turned around, and even then, I had to walk above the trail because it was all flooded. With the wind against my poncho, I felt a continuous flow of water into the tops of my boots, and I tried to hold the front and back of the poncho away from my legs, but the wind pushed it back. The temperature had dropped from the high 80s to the low 50s, maybe even the 40s, up here near 9,000′, and I was wearing a light, soaking wet shirt and shorts. I wasn’t really worried, because thunderstorms are short-lived and I still had snacks for energy and mobility to generate body heat, but I knew I was in for hours of discomfort.

The farther I walked, returning down the trail, the less violent the storm became, until it was just a gentle drizzle. But then the wind picked up, whipping the tall pines, just as I entered a burn area where there were dead trunks, snags, still standing. The trees and snags were creaking in the wind, and before long I encountered a big one that had just blown down across the trail ahead.

By the time I started back across the north face of the Sisters, the rain had stopped, but enough cloud cover remained to shade the trail and keep the temperatures down. My wet feet were getting really sore from picking my way over the volcanic cobbles, and I still had a few miles to go, so I popped a pain pill that gradually improved my attitude. As it turned out, when I got home and checked the official point-to-point mileage for the national trail, this was a 15-mile round trip hike, the longest I’d done in decades.

By the time I rounded the final peak and began to descend toward the trailhead, I could see the storm dumping a few miles to the west. My storm, the storm I’d prayed for and been blessed with!

July 8, 2019

First Steps in the First Wilderness Part 5: Early July

When I returned to the high wilderness in July, our monsoon was officially late. Hot, dry weather had intensified since June, with maybe a slight, tantalizing drizzle once a week, in the middle of the night.

But clouds were forming, and thunderstorms were producing rain nearby. I hoped that if I headed over to the peaks in the west, I might get lucky. And while driving up the highway, I did see a few fluffy clouds floating over the peaks ahead.

The canyon was even more of a jungle than before, and there was still a little stream flow from winter’s snowmelt on the peaks. New flowers were blooming to add to those I’d found before, fresh bear scat littered the entire trail, and birds were busy as ever. Gnats were especially annoying, and my energy came and went throughout the hike, so that in some stretches I had to stop and rest frequently, while in others I just powered my way up the steepest grades. I’m starting to learn that I need to take plenty of high-energy snacks and gulp them down regularly, instead of relying on a meal from hours ago.

During the climb, dark clouds covered half the sky above me, while the other half showed patches of blue. I couldn’t tell whether storms were moving toward me or away, but it was all beautiful, and with frequent shade the air stayed cool. I felt better on the upper stretch of trail and decided to go all the way to the crest, because the payoff here is the views at the very top.

On the way down, I decided to investigate the spring located just below Holt Peak, which dominates this stretch of the trail. I’d always thought it unusual to find a spring near a peak, but it sits on a steep slope above the trail, and I could see a cast-concrete spring box up there and figured it might be piped, so I hadn’t actually investigated it before. This time, I traversed across the slope of loose rock and deep pine needles, and discovered it’s a natural spring that simply drips out of a shallow bank on the hillside.

Normally I’m very careful about treating groundwater. But with no sign that this mountaintop had ever been grazed by livestock, and little chance that backpackers had ever camped above this spring since the trail bypasses it for more obvious destinations, I decided to have a drink. It was ice-cold, and delicious! It suddenly occurred to me that this was my best hike yet in this wilderness. My body was holding up well, the weather was great – I was still holding out hope for a storm – and I was drinking from the mountain, an experience that is always precious.

Sure enough, as I dropped down into the big side canyon, the dark clouds moved over, and a few drops began to fall. And when I reached the bottom, and the junction with the main canyon, rain began to fall in earnest, lightning struck somewhere nearby, and long avalanches of thunder began, lasting and reverberating between the canyon walls for many minutes.

I stopped, pulled my military surplus poncho out of my pack, and replaced it with my hat. But then the rain stopped and I was left carrying the poncho down the canyon.

Finally, about halfway down the canyon, a long spell of rain began and I donned my poncho. Even after the rain stopped, twenty minutes later, the air was cool and I kept it on, hoping for more rain later.

Sure enough, just as I reached the wilderness boundary a half mile from the trailhead, it really started pouring! My dream came true…

June 25, 2019

Summer Solstice 2019

Climbing the Soup Bowl

For more than a decade, I’ve been driving past this mountain on my way west from my New Mexico home. When I’m westbound, it’s mostly hidden behind lower hills, and I only glimpse it over my right shoulder. When I’m driving eastward, on my way home, I first spot it far in the distance, across the high grasslands, standing off by itself, isolated from the rest of its volcanic range. I always wondered what it would be like to climb to the top.

During those early years, its steep slopes were blanketed by dense conifer forest, slashed here and there by the avalanche scars of black volcanic talus. Then, eight years ago, the state’s largest wildfire, started by careless campers, swept across from the main bulk of the range and destroyed virtually all the mountain’s forest. I was sickened, but as more of our southwestern mountains were deforested by wildfire, I got used to hiking in burn scars, and came to view it as a chance to learn about ecological adaptation. So I figured I’d eventually end up hiking this one.

The Spanish called it the Soup Bowl because its top features large bowl-like meadows above 10,000′ elevation. It’s actually the state’s third-highest mountain. Since the fire, the dead high-elevation forests all over this vast range have been filled in by virulent green thickets of ferns, aspens, and Gambel oak.

The local offices of the Forest Service make little attempt to keep their public information up to date, so I was unaware until I reached it that the fire lookout tower on the peak had been damaged and abandoned after the fire. But the trail has been cleared by the incredible effort of sawing through thousands of downed trees.

Adding to the weirdness was an abundance of trash from recent hikers along the trail, all of which I gathered and packed out. I’ve never seen anything like this on a trail in New Mexico, even near town. I get the feeling that in general, Arizonans may be more likely to trash their habitats than New Mexicans.

Hard Lessons in the Interior

The next agenda item on my trip was to penetrate the interior of the mountains, a vast area with no paved roads and some of the worst devastation from the 2011 wildfire. It’s the watershed of the Black River, which is apparently famous among trout fishermen, and I knew that in the middle of it was an unlikely bridge over the river, by which I hoped to reach my next destination, a remote alpine lodge at the south end of the mountains. Along the way I’d get a feel for the landscape and the condition of the forest.

I’d spent a couple of nights in a resort village tucked away on the north side of the range, and I was relieved to be getting away, because hundreds of motorcyclists were converging on the village for the weekend, in convoys of a dozen or more that thundered through the alpine forest, dominating the sensory environment for miles around.

It was a long, slow drive on a rough road, winding along ridges, down into shallow, well-watered canyons, and finally to the rim of the canyon of the Black River itself, which is about 800 feet deep here. Ever since I spotted this place on a map, I figured it must be one of the most remote locations in the state. You do encounter little traffic on these back roads, but whenever you pass a turnoff, you can generally expect to see a group of big RVs and/or horse trailers parked back in the woods. Along the river beside the bridge were several parked vehicles, presumably for fishermen.

Across the river, the road rises steeply, and continues rising, higher and higher and higher, surmounting ridge after ridge until you can hardly believe there could be more. This is the edge of the Bear Wallow Wilderness, where the fire originally started. The climb from the Black River to this high country is 2,500′.

Near the top, I decided to take a side trip in search of a short hike. The side road I chose wasn’t bad compared to our desert roads, but my little vehicle has such a stiff suspension I felt like I was riding in a jackhammer – even the smallest rock in the road launched me into the air with calamitous thuds and rattles. I doggedly followed the road to its end, Gobbler Point, where there was a trailhead that was completely blocked by a couple of big trucks with horse trailers. And on the way back, I leaned over in my seat to reach for my camera, and instantly felt like I was being sliced in half at the waist. My dreaded back condition had been triggered, I’d be crippled for who knows how long, and my vacation was essentially ruined.

I carry pain meds for just this kind of situation. Fortunately my vehicle has seats with good lumbar support, and I was able to drive to a pulloff where I took a couple of pills and very carefully laid down on the pine needles to do my spinal twist stretch. It didn’t help much, so I got a beer out of the cooler and had some lunch, trying not to think of what lay ahead of me. The lodge I’d made reservations at is truly in the middle of nowhere, with no services to speak of, and no cell phone reception. I’d be pretty much on my own for the next couple of days, while dealing with paralyzing levels of pain.

The road seemed even longer on the way out. When I finally made it to the lodge, I was dismayed to find a big biker rally in progress. The entire front of the lodge was teeming with bikers guzzling beer and scarfing down barbecue. I was pale, my entire body tense with pain, when I carefully stepped out of my vehicle and edged through the mass of bikers and up the steps, walking like I was balancing a crate of eggs on my head. Taking my time and pretending to be normal, I checked in and somehow managed to carry my stuff up the inside stairs to my room on the second floor. It turned out to be tiny, with no space to lay out my stuff, most of the room hogged by the small iron bed. And of course there was no seating with adequate lumbar support, so it was either stand up, or carefully lie down on the over-soft mattress. I realized that sleeping on the soft mattress in my previous lodging had actually triggered the episode of back pain. It had been six months since my last episode, and I’d gotten careless, spending a lot of time lying on my back, which I knew I shouldn’t have done. I truly am vulnerable!

My back was even worse now, so I took another pill and crawled stiffly into bed. It was early afternoon, and I was hoping to feel good enough in a few hours to go downstairs for dinner. But the meds hardly helped. The entire lodge complex seemed to be operated by a single person, a small but rugged-looking woman about my age, and I realized that if I was going to eat anything, it would have to be with her help. But there were no phones in the room, so I’d have to get myself downstairs somehow to talk to her.

It took a while. Even the slightest wrong move could literally bring me to my knees on the floor, and that happened several times. I had to walk like I was on eggshells, but holding myself together also had a tendency to trigger an excruciating spasm. Eventually, pale and distracted, I found myself in the dining room, where three tables were already occupied. I fumblingly tried to explain the situation to my host, and she said she used to have back trouble herself and would be happy to bring something to my room.

But of course, there was no place to eat in my room. I found a card table and a folding chair on the landing at the top of the stairs, and rediscovered that folding chairs have great lumbar support, so that’s where I ate, with the host lady marching up to check on me every five minutes or so.

Back in my room for the night, I spent hours trying to find a position that minimized the pain and allowed me to sleep, but eventually I did.

Traversing the Rim

Of course, my back was even worse in the morning, so I took a couple more pills first thing, and made it into the shower, hoping the heat would do my back some good. The heat and the pills made it possible for me to walk stiffly downstairs for breakfast, and later to very carefully haul my stuff back to the vehicle after checking out.

I figured my trip was cut short and I should just try to get back home. There was the familiar route, north from the lodge to the highway that continues southeast to Silver City, or there was the unfamiliar road due south, which is longer but is the route I’d been planning to take. In view of my condition I turned north.

But after ten minutes or so on the paved highway, in my nice comfortable car seat, I was feeling bummed about leaving the mountains and guilty about wimping out. I’d originally planned to do a big hike today, ten miles or more, in this high country along the famous Mogollon Rim. Maybe I could just drive to the trailhead and conduct an experiment. After all, walking is supposed to be good for your back!

The road to the trailhead was at least as bad as the one on which my episode had been triggered, the day before, and even longer. But I toughed it out. And at the trailhead, I somehow managed to change into my hiking clothes, attach the tape and felt I use to protect my chronically injured foot, and get my heavy hiking boots on. I carefully shouldered my pack and started down the trail. I figured that if I fell and became immobilized, at least I had a couple more pills and my GPS message device…

This rim trail was clearly unmaintained since the fire. It followed an old stock fence which likewise had been abandoned and often simply disappeared, both fence and trail. But I managed to figure out where it went and rejoined it further on.

I went down a long hill, then up another, then down that, then up another, in and out of forest and raw clearings, always with a partial view off the rim to my left, over more wild, unknown country to the south. While temperatures were pushing 90 back home, up here it was in the low 70s, with an intermittent breeze. All told, I climbed four hills, detouring around fallen trees and losing and refinding the trail over and over, before finding myself in a saddle, facing impenetrable thickets and no more trail or fence. So I pushed my way a short distance through Gambel oak to the rim, sat on a rock and had lunch. The view south was dim with smoke, but I could just barely see the silhouette of the Pinaleno range, about 90 miles away, where I’d done several hikes earlier in the year.

Halfway back, I encountered a college-age couple dressed in the latest hiking fashions, and warned them that the trail ended only a mile further. Funny, in the Forest Service trail guide this is called a popular trail, and is shown to connect with other popular trails. The guide apparently hasn’t been updated since the 1990s, but they’re happy to give it out when you inquire.

Driving the Lost Road

Now that I’d experimented with my pain level by driving a back road and hiking a trail, I decided to experiment further by driving the unfamiliar road south. I had a sense it was daunting – long, steep, and full of hairpins – but again I felt guilty about taking the easy route.

This road turned out to be a revelation! Who knew there was so much remote, wild country tucked away in an area that looked small on the map? Far, far from any city, and with no apparent settlements or even ranches in 50 or 60 miles, as this road climbed down thousands of feet, then up thousands of feet again, over mountain range after mountain range I’d had no idea even existed. Along the way, there were dozens of signed turnoffs for campgrounds and trailheads, but few signs of people or vehicles. And every time the road crested a mountain, there was a scenic overlook.

About halfway down this road, I was suddenly tailgated by a big late-model truck, and I pulled over to let it pass. It was the college kids! They had given up on the trail even quicker than I had, and were racing to get back to the city, four or five hours away.

Enlightenment Now

In his best-selling book Enlightenment Now, the celebrity Harvard professor Steven Pinker promotes the notion that white Europeans have been making the world a better place ever since their “Age of Enlightenment” in the 18th century – otherwise known as the Industrial Revolution. A consummate urbanite, Pinker is totally oblivious to nature, ecology, and the services natural ecosystems provide. Hence he has no concern for the ecological impacts of industrial society, such as climate change – he believes that anything which enhances the urban, affluent Euro-American lifestyle is an unequivocal step forward for the species and its, preferably man-made, environments.

The end of my trip found me passing through a modern manifestation of Pinker’s Age of Enlightenment, which he would likely call one of humanity’s greatest achievements: one of the largest industrial sites on earth. The sun was going down, my back pain was getting worse, and I realized that I needed to find a place to stop for the night. Home was still three hours away and I wasn’t going to make it.

I pulled over to take another pill, and kept driving south. And just as the scenery was getting really spectacular, I caught a glimpse of an artificial mountain, a salmon-red tailings pile, looming far ahead. I knew I would pass the mine, and I’d even flown over it once not long ago. But nothing could prepare me for this.

It literally went on for about ten miles, just getting bigger and bigger, and although it was Sunday they were working full-bore, with huge trucks racing back and forth like ants across towering slopes, and clouds of dust rising like erupting volcanoes on either side. This symbol of man’s power to destroy nature must serve as an inspiration for new-age industrialists like Elon Musk, whose “gigafactory” wiped out a big swath of wildlife habitat in Nevada, and whose electrical technologies are dramatically increasing the demand for unsustainable mining of copper and other non-renewable metals.

The road twisted and turned and rose and fell through this nightmare landscape, then entered the processing area, and finally the company town. Then it dove into a deep, dark canyon and entered the old, original mining town, in which picturesque Victorian commercial buildings and tiny residential neighborhoods lined the slopes of side canyons along the San Francisco River. I took a wrong turn and ended up ascending a steep side street that reminded me of Los Angeles’ Silver Lake district, with expensive European cars parked outside well-maintained Spanish-style homes packed together like sardines.

Finally I arrived at the town’s only motel and pulled up outside the office, but it was unattended and there was no way to reach the owner. I would have to keep driving, another 45 miles south where I knew there were plenty of lodgings. I had just enough gas, and just enough light, to make it, to end this long day.