Max Carmichael's Blog, page 25

September 1, 2020

Hiking Through Trauma

First Sunday

My house fire occurred on a Monday morning. My neighbors were wonderful as usual, but the aftermath was an ongoing series of crises that fell on my shoulders alone. By Sunday I was a wreck.

I headed for the trail in the high mountains to the northwest, the trail where I can get 4,000′ of elevation gain and an expansive view of the tallest peaks. We were still in a drought and heat wave at home, but I was hoping for rain or at least cloud cover up in the mountains.

It’s an hour’s drive from my temporary accommodations to the trailhead. Suffering from PTSD, my heart fell when I rounded a bend, got a view of the canyons and peaks I’d be climbing, and saw smoke from a wildfire back in the wilderness near where I was headed. My first thought was that the trail would be closed by firefighting equipment.

I turned off and drove up the dirt road into the foothills. I passed a truck and encountered an older couple walking beside the road. They said they lived down in the valley and I asked them about the fire. They said the Forest Service was aware of it but wasn’t doing anything. That was both good and bad news. I could get to the trail but didn’t know if I could hike it safely.

The couple dismissed my concerns. “If you see smoke ahead, just turn around and hike out!” said the woman. This was the only trail this side of town that would kick my ass, which in my damaged state I mistakenly thought I needed, so I didn’t want to give it up. What pathetic animals we humans are!

The sun blazed down in the canyon, and the humidity turned out to be as bad as I’d ever experienced. My clothes were all drenched with sweat at the halfway point, so I stopped for lunch and hung my shirt and bandanna headband over branches, hoping they’d dry a little.

On the climb, a thunderhead finally began to develop in the east, moving over the crest. It chilled the alpine air but failed to drop any rain. From the little knob on the shoulder of the peak, I could finally see the fire, a few miles due east. It was one drainage away near the head of the biggest canyon in this part of the mountains, and its smoke was beginning to pour north over the ridge into a smaller side canyon.

I took a picture of myself up there, as usual, but I look too miserable to include it in this Dispatch.

On the way back to town I saw a serious storm in the east, and it turned out we’d finally gotten a little rain back home.

Second Sunday

The second week after my house fire was just as hard as the first, with more delays, contractors screwing up, daily arguments with insurance, and no hope of temporary housing. Constantly in reactive mode, I had no time to think about where I was going for my Sunday hike, so I just continued the cycle of west followed by east.

Walnut trees in the canyon, where the winding road approaches the crest, were heavily infested with tent caterpillars. I’d seen lesser infestations last year, but this was pretty creepy.

Maximum humidity again, with most of the day up there in the sky fully exposed to sun, so it was a pretty tough slog. When I got up on the crest I could see heavy smoke obscuring the lowlands to the east. I assumed it was from the California fires.

The long views from the crest are one highlight of this hike; the other is the old-growth fir forest, grassy meadows and fern dells on the back side of the peak. But this time I explored a new trail from the saddle behind the peak, and found a beautiful shrub swarmed by big orange and black tachinid flies – really impressive pollinators.

Third Sunday

The third week after my house fire was just as traumatic as the fire itself, because I had another apparent brush with death during oral surgery. And my trials at home continued, with only one encouraging break: I found temporary housing.

As the weekend approached, in rare moments of forethought I imagined driving two hours over to the Range of Canyons for a Sunday hike. It was looking like possible rain on the weekend, which would be the only thing that would make that trip bearable, since it’s a thousand feet lower and correspondingly hotter over there.

Unfortunately on the drive over, I jinxed myself by mentioning rain to a friend on the phone. So the day turned out to be rainless, as humid as the previous Sundays, but mercifully a little cooler due to continuous cloud cover.

The trail itself doesn’t have much to recommend it – the payoff view is too far for a round trip day hike, especially when you subtract the extra two hours of driving there and back. But despite the drought, I was surprised by the variety of unfamiliar flowers – most of them tiny – which don’t seem to grow across the border in New Mexico.

I also saw several white-tail deer, and a big hawk I flushed from undergrowth in the forest near the trailhead. It flew heavily off carrying some long, slender prey animal, and all I saw clearly was its tail, dark brown with broad, pale, clearly marked bands.

The hike felt harder than usual. I’d gone from 6 workouts per week down to one – my big Sunday hike – and I’d lost a lot of weight, all of it muscle mass. Probably 5-10 pounds, which is a lot for a little guy with no body fat. I’d tightened my belt and my pants were still threatening to fall off. From 22 miles and 6,000′ of hiking per week down to 12 miles and 3,000′. I was surely losing the conditioning I’d worked so hard to build up during the past two years of recovery from disabilities.

Despite the difficult week, this hike finally succeeded in calming me down a little, in preparation for more crisis and trauma in the week ahead.

August 10, 2020

Eve of Destruction

In my endless rotation of weekly hikes, it was time to return to the 10,000′ peak east of town. It was looking to be another hot day, but as usual during the monsoon, I was hoping for cloud cover and maybe even rain later in the day.

Starting from the trailhead I saw damp ground in the shade, evidence that it had rained last night or late yesterday. Vegetation was lush and humidity was high as the sun beat down on me. Since the first half of the 5-mile hike to the peak is exposed, I was racing to climb up into the shade of mixed conifer forest. And I was scanning the sky for clouds that might develop into thunderheads.

I’d gotten an early start, and I reached the peak shortly after noon. I immediately started down the backside on the continuation of the crest trail, into old growth firs and meadows deep with grass and ferns. I came across several deer and a small flock of wild turkeys, maybe the same I’d seen here a few weeks ago.

At the saddle that marked the end of the maintained trail, I decided to try fighting my way through the big blowdown that blocked the rest of the crest trail. It descends into a broad bowl that funnels into a ravine. The trail has been mostly obliterated. I climbed over log after log, found a remnant of the trail with a couple of old cairns, and continued down to the bottom of the bowl, where I faced even bigger logs. There, the trail ended in a heavily eroded gully where debris – piles of rocks – had filled in where the trail used to be. There was no clue where to go next, so I turned and fought my way back to the saddle.

On the return hike, moving slower, I noticed wildflowers I’d missed on the way in. I’m sure I’ve seen most or all of these before, but they seemed new and exciting. I heard thunder overhead, and it began to rain, but never hard enough to require my poncho.

The temperature up there dropped thirty degrees or so, and despite the sporadic rain, my sweat-soaked shirt soon dried out. I continued to make my way in and out of dark cloud shadows, rain, and brief spells of sunlight, enjoying the flowers along the way.

Finally I reached the highway and drove home.

The next morning I woke late, went to the bathroom, smelled smoke, and suddenly smoke billowed out of the heating vent at my feet. I ran outside in my bedclothes, yanked the basement door open, and saw my basement engulfed in flames. I ran back inside, called 911, rushed into pants and shoes, grabbed my keys and wallet.

My music studio is directly over the partial basement, so I raced in there and grabbed the two instruments I’d taken out of storage – my precious electric guitar and a cheap electric bass. Then I ran outside. Police were arriving, blocking off the street.

I moved both my vehicles out of the driveway. Finally after a few minutes, a fire engine arrived. Firemen ran hoses down my driveway. The police moved me out of the way, to where my neighbors were gathering. I couldn’t see what was going on at the back of my house, but smoke was coming out of my roof. I was terrified and in shock.

Much later, another fire engine arrived, and they ran another, larger hose to the back of my house. I asked for information but there was none available. I asked why there weren’t more engines and firemen, and they said this was all that was available now.

More and more smoke poured out of my house. After an hour or so, I could see firemen coming in and out through my front door. They’d opened all my windows. I was told the fire was under control but they had to clear the smoke. They set up a fan at my front door.

Looking down the alley, I could see a growing pile of blackened, sodden trash. They were pulling everything out of the burned basement. It was all my personal records – letters, cards, journals, research, projects, graphics, photos, etc. since earliest childhood. My camping gear. Old clothes and shoes. Nothing much of material value, lots of sentimental value.

Gradually, the firemen and police left. The fire marshall stayed for hours, investigating the source of the fire. In the end, he had no definite conclusions, but the water heater and old electrical wiring were possible culprits. There remains the question of insurance, which keeps me in a state of uncertainty.

My neighbors have been wonderful as usual. One fed me breakfast as I waited for the fire marshall’s investigation. I’ve moved into the guest room of their house next door. Every five minutes or so I remember something I need and return to my damaged house. The kitchen and bathroom are coated with black soot, and a toxic smell makes it hard to spend more than a few minutes in the house. But other than soot over everything, and the charred back corner of the structure, the damage is limited.

It’s sad because my builder was just finishing his restoration of my back porch, with its floor of antique oak tongue and groove. Most of his work has been destroyed, along with one end of the floor. All the utilities to my house have been disconnected, and I will need to hire an electrician, a plumber, and a licensed contractor to get everything going again. Not to mention the cleanup.

Living from minute to minute. So lucky I woke up as the fire was just starting! So lucky the firemen were able to stop it from spreading!

August 2, 2020

Lion Food

It was forecast to reach the low 90s in town, so I figured I’d head for the high country. I could do the Black Range Crest Trail to 9,700′ Sawyers Peak, a hike I’d only done twice before because it was less than 7 miles round trip. I could make it longer by fighting my way through another mile and a half of deadfall, or I could try a branch trail that might or might not be passable since the 2013 wildfire. Although it’d be hot at first, I figured there was also a good chance of clouds and rain in the afternoon.

When I got to the trailhead up in 8,200′ Emory Pass, there were already two other vehicles, plus a pile of stuff concerning a lost dog: a khaki jacket, a pile of dog food, and a note with a phone number.

As I hiked up the trail, I pondered the dog note. All dogs are supposed to be on leash on these trails, but nobody complies with the rule, hence the lost dog. And if their dog was lost, why did they leave? Why wasn’t the owner still here, waiting or looking for their dog? Why did they expect others to find the dog for them? If I’d lost something that important, I’d be camping out on the mountain.

A quarter mile up the trail I met a young guy with a camouflage backpack and an Aussie cattle dog. He said he’d been out here before dawn, scouting for elk, since he had a hunt coming up in November. He said he’d seen four bulls together, up around the peak. I wished him luck with the hunt.

A mile farther, I passed an older couple, also with an off-leash dog, who said they’d climbed the peak. A little farther and I reached the branch trail junction. I was starting down through the high-elevation forest, aiming for vague patches of tread, picking my way over fallen trees, when suddenly a dog barked up ahead. The lost dog!

I talked to the dog in a friendly way, and soon it came into view. It was a dark brown, short-haired little hound, and it looked on its last legs. Holding my hand out, I got it to come to me. It seemed in a state of shock or severe depression. It had a collar but no tag. It looked like it could hardly stand, let alone walk. As I walked past to check out the trail, the dog laid down in a depression it had made in the dirt under a ponderosa pine. I hiked another 50 yards and discovered there was literally no trail left to follow. I told the dog I’d be back later, and continued back to the crest trail.

With no branch trail I was doomed to battle deadfall past the peak. But I’d done it once before, and this time might be easier because I knew where I was going.

Traversing the side of the peak I encountered the four bull elk. They were in the standing snags above the trail, and their racks were huge. This was the first time I’d encountered a group of mature bulls in the wild, and it was pretty impressive.

I decided to skip the peak on the way in, and decide on my return whether to climb it or not – it’s only a few hundred feet above the trail. I continued south on the abandoned part of the crest trail as dark clouds moved over the range from the northwest. Finally, as I approached the grassy knoll that was my destination, I saw three young buck deer up ahead. It was a day for male ungulates!

The bucks took off and I climbed the knoll. Lightning and thunder had started farther north, and there wasn’t much cover up there. I crawled under a low juniper and ate a lunch of mixed nuts while I watched the storm come to me.

Rain started as I got up to start back. It was light at first, but by the time I got to the saddle below the knoll I had to unpack my poncho. By the time I was working my way up through the steep jungle of deadfall toward the peak, I was in a full hailstorm with lightning striking nearby and deafening cascades of thunder. Just my kind of weather!

When I reached the saddle below the peak, I decided to climb it. I hadn’t stopped thinking about that poor dog, but I wasn’t going to cut my hike short just for some fool’s pet. Besides, the dog could at least find some water now that it was raining.

There was no trail to the peak, and it was a difficult hike up broken, rocky ground with lots of deadfall. On the way back down, I strained my knee, which had been giving me trouble for the past couple of months, so I had to stop and put on a stronger brace. My pants and boots were soaked.

Continuing down the trail, I thought about the dog. I checked my pack and found a nylon strap I could use as a leash. And luckily, I’d brought two sources of meat protein – a venison bar and some salmon jerky. I’d give the salmon to the dog. And I could lay my poncho down in the dog’s dirt depression and fill it with water. I’d taken a photo of the stuff at the trailhead, and when I checked my camera, I discovered I could zoom in on the note and read the phone number. I was planning to give the owner a hard time. No leash, no tag, what were they thinking?

When I reached the branch trail, I took off my poncho so the dog would recognize me. I started calling it, and when I reached its little bed under the big pine, I saw it coming up the slope toward me.

I laid my poncho down and poured a little water into it, but the dog wasn’t interested in that. So I poured out the salmon jerky, which it ate, but not with much enthusiasm. Then I fastened my nylon strap to its collar and started leading it up toward the saddle. The dog soon balked and stood firm, and I couldn’t drag it forward. So I took the leash off.

I noticed it was a female. “Come on, girl!” I urged. I walked a little ahead, and the dog slowly followed, stopping frequently to sniff the ground. We continued this way, slowly, to the saddle, and then down the trail, me turning back frequently to encourage the dog. Soon we reached a couple of fallen logs that had to be climbed over. I crossed easily, but the dog seemed completely at a loss. She glanced from side to side, then turned around and walked away from me, her head hanging down.

I went back and called her again, and she came up. “Come on,” I said, patting the logs. She put her front legs up, and as I backed away, she finally climbed weakly over. It was as if she’d never seen a log before. Her entire attitude seemed one of shock and depression. I forged ahead, but after I’d gone a dozen yards I turned and saw she’d stopped again. She sniffed the trail, then turned and headed back toward her comfort zone. She was apparently just going to lay down and die back there under that pine.

Lion food, I thought. I’d been thinking about this for a while. People pride themselves on adopting “rescue” animals from shelters, animals that would otherwise be euthanized. The new owners are supposedly “rescuing” these animals from death.

I have a better idea. Pets make great food for wild predators. These clueless pet owners could actually help native ecosystems by donating their domesticated animals to the wild. Pets are ecologically negative – they only serve to damage nature; as food for predators, they would actually be helping nature. I did feel sorry for that dog, but it had already given up. Its spirit could live on in a mountain lion, a real animal with an actual, positive role in this ecosystem.

I reached a place where a couple bars showed on my phone, so I called the owner, but it went to voice mail. I told them where to find their dog and said if they really wanted her, they’d have to come and get her.

July 27, 2020

Getting Away

As Sunday approached, I’d been having trouble with chronic conditions in both my foot and my knee. I’d been using treatments that had always been effective on both conditions. The foot seemed to deteriorate with distance, whereas the knee was sensitive to elevation, so I figured I should do a little shorter hike with a little less elevation gain.

Our monsoon had started, so canyon hikes where flooding was a possibility were out of the question. I was all set to hike a peak in the Black Range, 7 miles round trip and less than 2,000′ of elevation gain, but something snapped when I got in the Sidekick.

I had to get away. I’d refrained from leaving my local area since lockdown began, last March. The Chiricahuas were an hour and a half and two counties away, across the Arizona border. But despite being across the border, the Portal area, in the northeast Chiricahuas, was more New Mexico than Arizona. The only paved road into that canyon was from the tiny unincorporated settlement of Rodeo, NM. And if I tanked up with gas, I could drive from my house to the trailhead and back without getting out of the vehicle, without interacting with strangers. Surely I could do that safely, just this once?

The Silver Peak hike entailed over 3,000′ of elevation gain, but was less than 9 miles round trip, and as I recalled the trail was in good condition and would be easier on my foot. Miraculously, on this beautiful monsoon Sunday, there was hardly any traffic into Portal, and the trailhead for this, the most popular trail in the entire range, was deserted. I wouldn’t see another soul the entire day.

Wildlife was reveling in the wet conditions. A hepatic tanager barely missed darting against my vehicle as I crossed the bridge over the mouth of Cave Creek. A big rattlesnake greeted me a hundred yards past the trailhead. Hawks and falcons swooped from ridge to ridge. Whitetail deer bounded through the trees from bottom to top of the peak. In the rockier drainages, water from recent rains was trickling down to the trail.

Despite this area being 1,000′ lower than my home, temperatures were mild, but humidity was high and my shirt was soon drenched with sweat. I figured I’d wait until I neared the peak, and rinse it out in runoff, but the higher I went, the less surface water I found.

Since this hike gains more elevation in less distance than any of the trails back home, it’s a relentless slog, and gets harder near the top. There must be a hundred switchbacks, many of them only a few yards long. Often stopping to catch my breath, sometimes after only a short rise gained. Always a relief to see the sky through the trees when you’re approaching the ridgeline.

Thunder clouds were growing, and I felt a few sprinkles near the top. Ladybugs covered most of the peak. From up there, I could see exactly where it was raining hard: over the encircling crest, to the west and south – although it also seeming to be pouring back toward home, way across the plains in the far northeast.

I took off my sweat-soaked shirt and bandanna, hung them over bushes, and sat down against the little shed below the ruined fire lookout. It had recently been vandalized. After a half hour my things were no drier, so I decided to hike down shirtless.

I hiked in and out of light rain and brief openings of sunlight. Finally, as I rounded the shoulder of the mountain and entered the Portal basin, the clouds pulled back and I was in full sun. A mile from the trailhead, I found a little waterfall and a pool of clear water to rinse out my shirt. That kept me cool all the way back to the vehicle.

Unfortunately for my foot, I realized that the last half-mile of the trail is the worst of our surfaces, a combination of loose and embedded rock, averaging fist-sized. This is probably one thing that will always trigger inflammation and limit my hikes – despite my stiff-soled hunting boots, prescription orthotics, and the biomechanical tape and felt I carefully apply before each trip. I recently read an online rant by an older hiker, complaining that big wildfires had removed soil and conifer duff from our trails, making them rockier, but I suspect these Southwest trails have always been tougher than trails farther north and east, or on the coasts.

Nearing the trailhead I encountered a group of three horses wandering through the dense oak forest near the paved road. One of them approached me, hoping for a handout, but I spread my empty hands and apologized. Sidekick was still alone at the trailhead. While hanging my shirt up to dry and loosening my bootlaces, I watched one of the horses rolling happily in the dust nearby.

Driving home, I could see a very dark sky ahead, and approaching town, I entered the rain. I’d been lucky, nothing had gone wrong, and maybe now I’d be content to stay near home for a while!

July 20, 2020

Return of the Rain

Our drought, and our record heat wave, ended Friday with the first of our delayed monsoon thunderstorms. So I headed out to the high wilderness Sunday morning looking forward to a cool day and possible rain.

What I found, working my way up the creekside jungle in the canyon, was an explosion of red raspberries, and humidity so high my clothes were literally drenched with sweat before I’d reached the halfway point.

As I climbed the switchbacks toward the crest, thunder rumbled from within a dark mass of clouds to the southeast. The illegal cattle I’d surprised in the canyon a month ago had continued to follow the trail upwards, leaving their pungent cowpies on the trail and attracting flies that swarmed my dripping face.

A cold wind chilled me as I traversed to the final saddle. I could see curtains of rain behind me, out west over the plain. I’d gotten a late start and would stop at the little hill topping the eastern spur of the peak. The cows had been there before me.

My return trip down the canyon was slowed by foraging on raspberries. Bears had been up and down this trail as recently as this morning, eating voraciously and pooping copiously. It was shadier and cooler than earlier and my clothes had partly dried out, when it started to rain, pretty heavily, so I pulled my poncho out of the pack. After that, the problem was pushing my way through the thorny jungle without ripping the thin poncho to shreds.

The rain ended before I climbed out of the canyon, but on the drive home, I was rewarded by several rainbows.

July 13, 2020

Closer to the Sun

A heat wave across the entire Southwest had brought us record high temperatures, compounding the stress of our already unusually hot pre-monsoon in May and June. Our monsoon rains were delayed for at least three weeks, and the entire landscape was super dry.

During the week, I’d continued my afternoon hikes near town, because although it was in the high 90s at home, it always felt cooler in the forest. Now, on the weekend, I was hoping to find lower temperatures on the crest, 2,000′ to 4,000′ higher. And if not cooler temperatures, at least a breeze.

On the narrow highway winding up the canyon toward the pass, I was approaching a blind, shaded curve when I suddenly realized a tree had fallen across the road, and there was a log blocking half of my lane. I slowed and carefully drove around it. There was no cell signal here, so I continued to the pass, and after ten minutes of fumbling with automated directory assistance, managed to reach the local office of the state police.

A young woman answered, and I told her about the log blocking the highway near Emory Pass.

“What mile marker?” she asked.

“I have no idea, but it was just east of the Iron Creek Campground.”

“Sir, what was the mile marker?”

“Ma’am, I was driving and I didn’t have a cell signal until I reached the pass. But you can find it on any map, it was between Iron Creek Campground and Emory Pass.”

“Sir, I need the mile marker.” Silence. The signal was broken.

I shouldered my pack and locked the Sidekick. It felt just as hot up here as at home. I wondered how far I would get. I’d filled my 3 liters of water bottles with all the ice cubes in my freezer, but I knew they’d all be melted before I got halfway through the day. At least they’d be cooler than the air.

The first half of the hike is totally exposed, through the burn scar, so I raced up the trail, sweating profusely, aiming for the shady forest around the peak. In a minor miracle, a cloud mass was growing outward from the 10,000′ peak, and halfway through the hike, it covered me with blissful shade that lasted for most of the rest of the day. In the shade, it felt like the low 80s; whenever the sun hit me it felt like the high 90s.

The flowers were less spectacular than a month earlier, and the big butterflies had been replaced by swarms of little butterflies. When I reached the trail junction at the peak, in its rain forest-like habitat of old-growth firs, lush grass and tall ferns, I noticed something out of the corner of my eye. It was a buck deer, youngish, lying down in the shade of the firs, about 40 feet away. He watched me without moving – he’d found the perfect resting place on a hot day and wasn’t anxious to give it up.

I hiked down the back side of the peak to a saddle 1,000′ lower, where the trail is blocked by a massive blowdown. I hung out there for a half hour or so, then did a leisurely climb back up the slope. The buck was still there, two hours later, but now he was surrounded by a flock of wild turkeys. As I stood watching, the tom turkey fanned out his tail in a display for the ladies, while the buck watched in seeming amusement. Peaceable kingdom on a hot day!

Driving down from the pass, I came upon a group of tourists, with two vehicles stopped in another blind curve of the oncoming traffic lane, doing something with their two vehicles, oblivious to the fact that they were blocking a state highway. I passed them and cautiously approached the bend where the tree had fallen across the road. The log was still there in the eastbound lane, eight hours later. But farther on, closer to town, the state police had set up a speed trap. Just in case you survived the log in the road, they were there to write you a ticket.

June 29, 2020

Year of the Butterflies

It’s been going on since early springtime, and I can’t keep quiet about it anymore.

There are more butterflies this year than ever before! I have no idea why. Are their predators in trouble? I don’t even know who their predators are.

First the small ones, yellow and white, along the wilderness trails. Then the bigger ones, in my yard at home. By now they’re darting and sailing back and forth all the time – I often mistake them for birds.

Landscape

I returned to my favorite local trail, the one with over 4,000′ of elevation gain that takes me to a peak with a view of the interior of the mountains. It’s more of a struggle each time, because more trees have fallen or been blown down across the trail.

Birds

Hectic time of year for birds, too! Turkey vultures and hawks circle overhead as mother quail shepherd their tiny young across the road. As I traverse stark burned slopes on the peak, the boomerang shapes of white-throated swifts rocket past my shoulder. And in the forest from canyon bottom to ridgetop, constant calls and song from a diverse community. Birds are less timid, often allowing me to walk right past them.

Flowers

In the lead-up to our monsoon, as the heat rises, the air dries out, and the creek dwindles, the first wave of flowers reaches its peak.

Butterflies

On the way up the mountain, I just enjoyed the butterflies. But on the way back, in the canyon bottom, I suddenly reached a large clump of Monarda where butterflies were converging from all directions, and I stopped in their midst to photograph them as they ignored me and went about their business.

June 23, 2020

Songs I Wish I’d Written

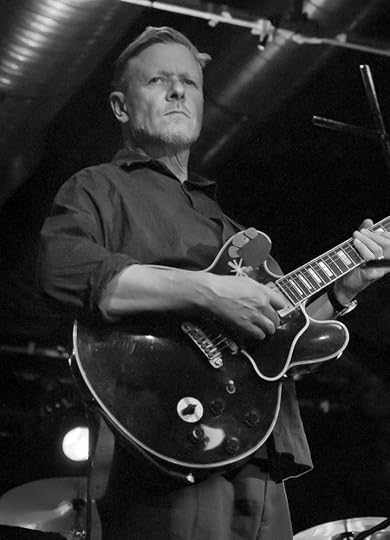

Michael Gira by Andy Catlin

Writing Songs

I began studying music in school when I was 9, learned the saxophone when I was 10, and started playing guitar when I was 11. I started a band with friends at age 12 and became the lead singer. I had my first poems published in high school at age 15, but I didn’t put words and music together, writing my first song, until I was 17. Believe it or not, I called it “The First Song.”

Writing songs was fairly easy for me as long as I followed the familiar formulas of American and British popular, rock, and folk music. But in the fall of 1980, inspired by punk, post-punk, and the incredible variety of music around me in the San Francisco underground, I woke to broader horizons. I began deconstructing everything I knew about music and experimenting in all directions. I had no preconceptions about song structure. I was interested in raw sound, ambient sound, free improvisation, rhythm before melody.

That was liberating for a while – I actually stopped writing songs and just improvised freely with my new band, Terra Incognita. But in 1982 I discovered African music. And that made it harder, because I took on the challenge of creating a new genre that would infuse my Appalachian roots with what I was learning about African music. Unlike what David Byrne was doing or what Paul Simon did years later, it wouldn’t sample or imitate African music. It would sound like nothing anyone had ever heard.

It was a long struggle. Finishing a song was incredibly hard, and they only emerged in bursts, a handful at a time, with years in between. I was seldom satisfied with them, and kept reworking them, re-recording them, performing completely different versions with different lineups of Terra Incognita. I believed the rhythm and musicality of the lyrics was more important than the words, but I agonized over the words for years anyway.

That’s one reason why I’m blown away when I discover that someone else has written a song that perfectly expresses something I’ve felt or experienced. Why couldn’t I write that? Why has it been so hard?

What Makes a Perfect Song?

What makes a perfect song? There’s really no formula. I love ambiguous, mysterious songs, but I also love songs that are simple, direct, and didactic, like “Nostalgia,” or even “Whole Lotta Love.” The didactic songs can become classics, but ambiguous songs can give us more over time, revealing hidden depths.

How do you write an ambiguous song? I don’t think you do. I think you write a song that means something clear to you, but is so personal that it seems mysterious to others. When I analyze the lyrics of songs that I like, I often find that it’s only the chorus, or a single repeated phrase, that endears it to me. The rest of the lyrics may seem like gibberish. After all, I love many songs in other languages that I can’t understand at all. I’ve believed for a long time that the overall musical impression is far more important than the lyrics.

I mostly shun the mainstream of pop music – Elvis, The Beatles, The Stones, Michael Jackson, Madonna, Prince, Lady Gaga et al. But whereas I’ve mostly written songs that are obscure – about the ancient Moundbuilders or the geological decomposition of granite – some of my favorite songs are pop standards from various eras, like Charlie Chaplin’s “Smile,” “The Way You Look Tonight,” “Unchained Melody,” “Scarlet Ribbons,” “Can’t Help Falling in Love,” and rock hits like “You Really Got Me,” “Hang On Sloopy,” “Wild Thing,” and the Cure’s “Friday I’m in Love.” I definitely wish I’d written those.

Then there are traditional songs from my Appalachian heritage that I’ve covered with my bands and have been inspired by, but can never match, like “Working on a Building” and “Rank Stranger,” and songs in the Yoruba language like King Sunny Ade’s “Ja Funmi” and Paul I. K. Dairo’s “Mo Wa Dupe,” which have inspired me to venture outside the narrow focus of Western pop themes.

Leaving out the classics and hits most everyone’s familiar with, the traditional country repertoire and the African songs, here, in chronological order, is a partial sample of less well-known songs I wish I’d written.

Boomer’s Story (1972)

Written by early country singer/songwriter Carson Robinson and recorded in 1972 by Ry Cooder, this song is an instance of serendipity for me. It’s the story of an old hobo, and I began riding the rails myself in 1978, about the same time that my high school friends discovered Ry Cooder and his album of the same title. The lyrics perfectly capture the harsh romance of riding the rails and the premature but deeply-felt sense of world-weariness that we twenty-somethings had by the late 1970s, after coming of age during the Vietnam War, the environmental and civil rights crises, and Watergate.

Final Day (1979)

I discovered and fell in love with the Welsh post-punk trio Young Marble Giants at an underground arts festival in San Francisco in 1980. Their stark, minimal, somehow primitive sound showed that post-punk was never a coherent genre, but a broad spirit of deconstruction, exploration, and experimentation.

Fear of the Bomb permeated my childhood in the 1950s, but it wasn’t until the aftermath of the Three Mile Island nuclear disaster in 1979 that YMG produced the perfect song about nuclear holocaust. This was another serendipity for me, because when I first heard it in 1980, I’d just started having the nuclear holocaust nightmares that would plague me for decades.

Atmosphere (1980)

This is not the only Joy Division song I wish I’d written, but I sometimes think it’s my favorite. Like so many great songs it’s completely ambiguous yet captures in powerful imagery the gamut of human feelings in a relationship, from tenderness to mistrust and fear.

I’ve included the video version by Joy Division bassist Peter Hook and Rowetta, because it perfectly captures the spirit of Ian Curtis’s original, whereas the imagery of the official video distracts from the lyrics.

Nostalgia (1982)

After Young Marble Giants broke up in 1981, singer Allison Statton formed Weekend, another Welsh outfit that wrote and played generally bright, ethnic-inspired pop music, released in one studio and one live album.

They also covered old standard ballads, and wrote the painfully didactic song “Nostalgia,” which has been one of my all-time favorites since Weekend was introduced to me in 1982 by my San Francisco loftmate and former best friend Tiare.

I’ve included the version from their extremely obscure live album, Live at Ronnie Scott’s, because it’s better than the studio recording.

Up on the Sun (1985)

My former songwriting partner Katie introduced me to the band’s breakthrough album Meat Puppets II when we first met in 1984. We listened to those punk-inspired tracks while driving around Los Angeles, then we listened to their more laid-back third album, Up on the Sun, when we drove out to camp in the desert.

I’ve started many songs while stoned, and I’ve worked on many songs while stoned, but I’ve never finished a song that’s as perfect a stoner anthem as this. What I love most about the Meat Puppets and Curt Kirkwood’s lyrics is that they so often evoke nature and living outdoors and the mystical sensations we campers and hikers share even when we’re not high.

Although the Pups are an awesome live band with a rabid cult following, I’ve included the album version because their shows are never recorded with an adequate audio mix.

Pictures of You (1989)

By the time this song was released, I’d been deep into my obsession with African music for years, and I shunned the vast majority of rock music, not to mention the goth subgenre The Cure came to be labeled with. It wasn’t until two entire decades later that I heard their poppy “In Between Days” on the radio, and digging deeper, I discovered “Pictures of You,” which made me a long-belated Robert Smith fan.

He’s penned a whole slew of songs I wish I’d written, but this one so perfectly expresses the nostalgia I’ve felt, and unashamedly embraced, for lost love affairs. In my humble opinion there’s nothing more worth singing about.

The Maker (1989)

Whereas The Cure were completely off my radar in 1989, I was open to Daniel Lanois’s album Acadie when a mutual friend suggested it to Katie, my former partner and bandmate, because its Acadian – Cajun – focus fit into my fiercely traditional, mostly ethnic aesthetic.

The lyrics are almost too perfect an example of a modern gospel song, the kind of devotional confession I have tried to write with less success.

I’ve included the stripped-down live version because live is usually better and the official video sucks, and best of all, Daniel is playing a Fender Jazzmaster with clear finish, exactly like my first Jazzmaster, a now-classic guitar purchased for $75 back in 1978. But if you haven’t heard the perfect studio recording with Aaron Neville, check that out ASAP.

Breakdown (1993)

Dot Allison and One Dove are examples of how worthless the consumer economy is at promoting and sharing things of real value. I’ve had hilarious conversations with music fans who get all huffy because I don’t worship the biggest pop stars, while much greater artists die without ever achieving significant recognition.

At least One Dove’s “Breakdown” made it into a movie, a corny 90s comedy that I’ve never seen. Dot Allison went on to have an equally obscure solo career, and I didn’t discover her work until 2011 after I resumed my own musical ventures. “Breakdown” is a better pop song partly because of how unpopular it is.

Get Me (1994)

Although Everything But the Girl started during the early post-punk era, they weren’t big enough at the time to show up on my radar, and by the time they reached a wider audience, in the 90s, I’d driven my obsession with African music into the ground and was about to be turned on to grunge.

I was deep into the grunge thing when I joined Katie on her family’s ski trip in early 1995 and heard Tracey Thorn for the first time on Massive Attack’s hit album. You can keep your mainstream divas, your Annie Lennoxes, your Madonnas, your Lady Gagas, but I’ll take Tracey any day. Eventually, I went back and discovered her earlier work, and although Amplified Heart has several outstanding tracks, I picked this one, attributed to her partner Ben, because it never became popular, despite its perfection as a conflicted love song.

Blind (1995)

Michael Gira seems to have been the classic troubled artist, growing up in an alcoholic family, spending lots of time in jail. As with a lot of my now-favorite artists, I discovered him after resuming my musical career in 2011 and only know about him after the fact, never having followed his early career and cathartic performances in Swans.

But I keep “Blind” in regular rotation in my playlists, because it’s one of those gemlike songs that express some essential realities of our species in a harshly beautiful nutshell.

Protection (1995)

This is an instance where I break my rule and include a song that became a fairly big hit – although never really in the pop mainstream. I believe it became such a big hit partly because the time was right for electronic pop music, but mainly because Tracey’s message is just what we all need, all the time, in our conflicted, violent, dangerous world.

Although Massive Attack’s studio version is perfect and their official video is cool, I’ve included Everything But the Girl’s live version because it’s a decent recording, and it has Tracey!

Ribbon on a Branch (2007)

Younger Brother is a somewhat obscure electronic duo who took their name – one of my favorites of all time – from the mythology of a Colombian indigenous tribe. I discovered “Ribbon on a Branch” in 2011 and am reminded of it every time I hike a trail in our local wilderness and spot a pink ribbon on a trailside branch. It’s a love song in nature, something I’m always aspiring to write. Get outside, you alienated city people!

This live video has a long intro, but the sound is excellent so hang in there!

No Cars Go (2007)

Perhaps not as big as Massive Attack’s “Protection,”, “No Cars Go” was still a hit single by stadium rockers Arcade Fire, so it probably shouldn’t be on this list. But despite its bombast, I respect it because it not only trashes cars, it says space ships are uncool, too. As in Radiohead’s OK Computer, Arcade Fire are dissing a sacred cow of Gen-Xers and Millennials, which is ironic since both bands are heroes to those generations.

The Never Ending Happening (2012)

Bill Fay is an old hippie from the 60s who has languished in obscurity for decades, like most great artists. It shows how irrelevant our sacred cow of progress is that he released this perfect hippie anthem in 2012. It’s like a modern, ecologically woke but painfully self-conscious version of the old gospel hymns that have inspired me. It’s liable to make me cry every time I hear it.

Black Monday (2016)

This urban anthem by an obscure SoCal band is a perfect post-punk song that should’ve been written in the late 70s or early 80s. I can never hear it enough and end up singing along and laughing every time I do.

Which video of this song to include was a tough decision! Hilariously, this live version used sound that is obviously dubbed from their studio recording – you can tell 2/3 of the way through when backing vocals mysteriously kick in on the verse, but nobody else in the band is singing. The official video has a bunch of clips that are supposed to add narrative value, but the band looks half-dead. Take your pick!

One With the World (2016)

Rambling Nicholas Heron is a Swedish folk singer/songwriter who writes and sings in English. I love his songs, but rare videos suggest that his sincerity might be tempered by a trace of irony.

No matter, this example, which has apparently never been recorded apart from YouTube, is another perfect gem of the civilized yearning for connection with nature.

June 21, 2020

First Steps in the First Wilderness Part 11: Summer Solstice

The same day I was hit with the worst of my biannual back pain episodes, a lightning strike started a forest fire in one of my favorite hiking areas. While I was immobilized on pain meds, the fire grew to engulf the entire ridge, turning the beautiful north slope into a moonscape.

After two weeks the pain faded and I got back on my feet again, but, what with COVID-19, I wasn’t able to plan a solstice trip, or make any sort of plans for this special day. After another week of short walks and moderate strength training, I was anxious to find out if I’d lost any conditioning, so I returned to another one of my favorite trails, the ridge in the sky.

It was going to be a hot day and I hoped it would be cooler up there between 8,000′ and 10,000′. No such luck, but at the top, the trail passes through some shady groves of old-growth pine and fir, which provided some relief.

Despite the heat, the flowers were amazing, butterflies and other pollinators were everywhere, and it was great to be hiking again, on the longest day of the year. And I surprised myself by going up over the peak, down the back side, and returning the same way for 12-1/2 miles and 3,140′ of elevation. Not bad after 3 weeks off!

First Steps in the First Wilderness Part 10: Summer Solstice

The same day I was hit with the worst of my biannual back pain episodes, a lightning strike started a forest fire in one of my favorite hiking areas. While I was immobilized on pain meds, the fire grew to engulf the entire ridge, turning the beautiful north slope into a moonscape.

After two weeks the pain faded and I got back on my feet again, but, what with COVID-19, I wasn’t able to plan a solstice trip, or make any sort of plans for this special day. After another week of short walks and moderate strength training, I was anxious to find out if I’d lost any conditioning, so I returned to another one of my favorite trails, the ridge in the sky.

It was going to be a hot day and I hoped it would be cooler up there between 8,000′ and 10,000′. No such luck, but at the top, the trail passes through some shady groves of old-growth pine and fir, which provided some relief.

Despite the heat, the flowers were amazing, butterflies and other pollinators were everywhere, and it was great to be hiking again, on the longest day of the year. And I surprised myself by going up over the peak, down the back side, and returning the same way for 12-1/2 miles and 3,140′ of elevation. Not bad after 3 weeks off!