Max Carmichael's Blog, page 13

April 3, 2023

Wilderness Closed for Repairs

I was tired of driving to Arizona for lower-elevation hikes, and was hoping that the recent warm weather had melted most of the snow on our mountains below 9,000 feet. But I knew that my favorite high-elevation trails would still be blocked.

Reviewing the topo map one more time, I saw a trail up on the west side of the wilderness that I’d never noticed before. Starting at only 5,100 feet, it climbed to over 9,000 feet, eventually joining one of the crest trails, but it took it a while to get there, so even if I ended up blocked by knee-deep snow, I’d still get some decent mileage and elevation. I had no idea what the condition would be, but I found a note online saying part of it had been worked on last year, so I was optimistic.

Weather was forecast to be clear and warm, but we’d been in our windy season for the past month, and today there was a “red flag” fire weather warning as well as a dangerous wind alert.

The map showed this unfamiliar trail beginning along a road drawn with the same heavy black line as the paved road it branched off from – a road I’d driven many times. But that first road is narrow and twisty, and I missed the turnoff, coming to the stream crossing on the main road, which I’d completely forgotten about.

This is the big perennial creek on the west side of the range, draining a fifty-square-mile watershed ringed with peaks over 10,000 feet tall. The road crossing is simply a shallow concrete dip in the road, where the creek normally spreads to no more than an inch deep. But after our heavy snows and warming weather, today it was a raging flood. And because it flowed to my right, I knew the access road for my trail would also cross it.

I turned around and found my access road a quarter of a mile back. Despite having the same line on the map, it turned out to be a little-used gravel road. And the creek crossing looked bad.

Because I’ve never had a serious high-clearance vehicle, I’ve never gotten really comfortable with stream crossings. This one had a submerged berm of rocks on the downstream side, but the water was too cloudy to tell how deep the crossing would be. I’ve crossed creeks up to about 8 inches deep, but I was afraid this might be a foot or more. If I got submerged above my door sills, the flood might exert enough force to wash me downstream into deeper water.

As usual, I decided to try it anyway, switching into 4wd low range and rolling slowly down the bank into the flood.

All that water raging around the vehicle sounded and felt scary, but I successfully rocked and rolled across and climbed the opposite bank, where I stopped to get out and see how high the water had reached.

My vehicle’s minimum mechanical ground clearance is 8.5 inches, and the door sills are 16 inches off the ground. The water level at the front had barely reached the bodywork, but the wake had pushed about ten inches higher toward the back. I wasn’t shaking in terror, but I wasn’t looking forward to doing it again.

The road on the opposite side continuously deteriorated as it climbed along the foothills, eventually reaching a washout with ruts requiring all my ground clearance, followed by a stretch where a side creek flowed down the road surface, two or three inches deep. I got out and walked up it a ways in my waterproof boots. It would be driveable, but I was still worrying about the previous crossing. I’d always heard and assumed that snowmelt streams flow light in the morning and heavy late in the day. I was frankly afraid the crossing I’d survived would be impassable when I returned from my hike, and I hadn’t brought camping gear. So I turned around and carefully recrossed the flood.

At this point, my only option was the final remaining west side trail with access to the crest. This is my old favorite, and since last November, I’d been anxiously waiting for the snow to melt enough to make it accessible. Now, the snow would likely still be knee-deep on the crest, but at least I could do the climb, for up to 9 miles and over 3,000 feet of elevation gain.

On the drive up the dirt road to the trailhead, I passed a late-model minivan with Texas plates and a fancy roof box, parked in a clump of junipers. Then at the trailhead log, I was surprised to find a whole page of visits recorded since November, with most in the past month. They were from all over – New York, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Wisconsin, Alabama – not just the western states. In the past, this trail has remained a well-kept local secret, going up to two weeks without a recorded visit, especially in the winter and summer. But after my initial surprise, I realized that it’s the last remaining entry point to the west side of the wilderness – all the others were washed out last year by catastrophic monsoon floods.

And unlike me, virtually every other hiker is either casual – only venturing a mile or two into the canyon – or if more ambitious, they’re taking the branch trail to the old prospector’s cabin in the next canyon over. In the general public, more people are drawn to historic man-made structures than to true wilderness.

One log entry, a couple weeks earlier, mentioned “trees on trail”, but I ignored that. There’d always been a few fallen logs on this trail.

I’d had food poisoning two days ago and was only gradually recovering. I found myself fatigued and short of breath, nearly as bad as after my hospitalization last spring. A short way up the trail to the wilderness boundary, panting heavily, I saw a trail runner approaching – a slender guy in his late 20s, the minivan driver. The trail was narrow and the slope was steep, but with difficulty I used the edges of my boots to sidestep up enough to give him space. I smiled and called good morning, but with barely a glance and no change of expression, he brushed past me silently. Locals would return your greeting and thank you for yielding right-of-way.

The way into the canyon is through a stark burn scar from the 2012 wildfire. The creek in the bottom was flowing about as expected – this is one of the smaller watersheds on the west side. A few hundred yards up the canyon bottom, you leave the burn scar and enter the only-patchily-burned canopy, and it gets pretty – mature ponderosa and Doug fir, maple and Gambel oak, and lichen-encrusted boulders, with the creek flowing briskly and noisily over rocks in its bed.

Spring flowers were spreading and checkerspot butterflies were out in force. But before I reached the branch trail there was an ominous sign – a mature ponderosa snapped off on the opposite bank, its yellow heartwood a chaos of splinters.

I reached a creek crossing dammed and flooded by a perpendicular log which had clearly been there for a while. It made the crossing much more difficult, and it was an easily removed small-diameter log, but none of the other hikers had thought to remove it. Weird. I pulled it out of the way, the flood quickly subsided, and I crossed easily.

Two miles in, past the branch trail, I met the blowdown. And it just got worse, and worse, the farther I went. Living pines and firs, at least half of them between two and three feet in diameter, had either been uprooted or snapped off like twigs, and much of the ground was blanketed with foliage that had been blown off crowns of surviving trees.

The damage was selective – most of the canopy survived. But the wind event had opened the forest enough that I could now see the rock towers that line the slopes just above the canyon bottom.

In my weakened state, as I climbed over and through obstacle after obstacle, the only thing that kept me going was the belief that conditions might change at the switchbacks, a mile and a half beyond the branch trail.

Conditions did change, but there was one final giant down across the trail right at the base of the switchbacks, like a grand finale – a ponderosa 30 inches in diameter. And after climbing over and past it and starting up the loose dirt of the upper trail, I began to discern the tracks of the only other hikers who had gotten this far in the past months – a medium-sized man and woman.

There was blowdown on the switchbacks, but only the smaller-diameter trees that can mature on these steep upper slopes, and less of them, indicating lower wind speed. I kept encountering branches and small trees blocking the trail that could easily be moved, but the couple before me hadn’t moved them, despite the fact they’d had to repeatedly step around, going up and coming back down. I moved all these out of the way myself and wondered, not for the first time, at the cluelessness of people venturing into nature these days. I’m sure many if not most are urban novices whose only preparation is the GPS on their smart phones, and who, like that trail runner, are trained to ignore strangers.

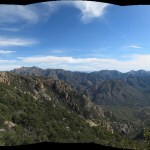

My stomach was still recovering, so I was not only weak and out of breath, I was actually feeling sick. But with well more than half my time gone, I reached the rock formation with a southwest view where I’d stopped on my first attempt at this trail, 4-1/2 years ago.

My left knee began hurting on the descent, which was otherwise much easier on the rest of me – even climbing over all that blowdown in the canyon bottom. But the day had been just as discouraging as so many hikes in the past year. The equestrian trail crew the Forest Service has authorized to do trail work is not equipped to cut these big-diameter trees, and it may take USFS years to get funding for their own effort. And if there was a blowdown here, there were likely blowdowns elsewhere. Three of the five other wilderness trails on the west side were already blocked by flood damage – now there’s only one left, and it doesn’t access the crest. So the crest is now only accessible to a very tiny minority who are even more hardcore than me, willing to accept an experience which is more obstacle course than trail.

March 27, 2023

Trashy Beauty

Still looking for lower-elevation trails, I wanted to try a new one over in Arizona this Sunday. But surprisingly, there was no room at the nearby inn. My second choice was the abandoned, flood-damaged, overgrown trail farther south that had defeated me in early February. I wasn’t really looking forward to the bushwhack, but it’s a pretty canyon and I was still hoping to reach the “Indian cave” and the prominent rock formation at the head of the canyon.

Whereas on my previous visit, I’d been alone in the valley of the remote “ghost town” that leads to the trail, this time I passed two vehicles and a jogger on the road in. And as I approached the sycamore-shaded creek crossing, the water level seemed surprisingly higher.

The creek was higher, but forgetting about all the crossings, I’d brought my non-waterproof boots. Since all the snow was long melted off this low part of the range, I’d expected less water in the creek, but it was just the opposite. In fact, as I made my way upstream and more bedrock was exposed on the surrounding slopes, water was streaming down the surface in glistening sheets. Apparently the peaks and ridges above are porous, collecting and storing snowmelt all winter and releasing it slowly in spring.

The sky was clear, the air temperature was mild, and I was under riparian canopy in the bottom of a narrow canyon, but when I stepped out of my vehicle I was hit by a bitterly cold wind, which tugged at my hat and sucked at my body heat the whole day long.

As before, I found no other human tracks as I scrambled up the first mile-and-a-third of catastrophically washed-out forest road, climbing up and down sheer drop-offs, crossing and re-crossing the rushing creek. But I did find recent tracks and scat from both cattle and what seemed to be wild burros or horses.

The road ends at the abandoned cabin, where two creeks come together, and my trail leads up the right-hand creek. But before the catastrophic floods, the road continued up the left-hand creek, and I suspect that road is still mostly intact above the canyon bottom. Heading up my trail, I immediately found the tracks of three recent hikers, who I assumed came down from above on the upper road, which can be reached from the opposite, west side of the mountain range. When I checked the map that night, I saw they could actually do a 12-mile loop from the paved road in the national monument on the west side, using a combination of trails and forest roads, with presumably the hardest part being the canyon trail I was taking.

I’d expected my previous experience to result in an easier hike than before, but it actually felt even harder this time. Harder to distinguish remnants of the hiking trail from cattle trails, harder to relocate the trail after long scrambles up debris flows in the creek bed, harder to avoid the thorny shrubs on the banks, harder to get around log jams and thickets. I was already discouraged by the time I reached the first washed-out tributary, where I’d mistakenly looked for the cave last time.

And at one creek crossing, I found a rolled-up blanket up on the bank. One of those cheap, lightweight, synthetic fleece things – I couldn’t imagine anyone actually backpacking with it in our 30-something nighttime temps. I assumed it had fallen off the backpack of one of those three recent hikers, and they hadn’t missed it until it was too late to go back. But it set the tone for the rest of the day.

Past that tributary, more bedrock is exposed in the canyon bottom, and if anything, the way gets even harder. But I still hadn’t come to the “narrows” which the trail guide mentions – based on second-hand historical sources, because nobody’s actually surveyed this trail since the 2011 wildfire.

Passing the point where I’d turned back in February, I came to a massive log jam across the canyon, and climbing around it, reached a sandy ledge with an old fire ring. The previous hikers had tramped around here before continuing up canyon.

Finally I reached the “narrows”, where the canyon forms a “V” of stone, and the creek has cut a sinuous channel with many semi-circular hollows, deep pools, and small waterfalls. Here, I found a few decades-old trail improvements – including one walkway across a steep rock face, reinforced by half-rotted logs anchored by rebar sunk into holes drilled through the rock.

It was really tricky walking in the bottom of the V, climbing past the waterfalls, trying to avoid slipping into the three-foot-deep pools of ice-cold water. I fell twice, each time barely avoiding injury. But it was a beautiful stretch of canyon, full of sound from the roaring creek and full of light from the glistening sheets of water flowing down the bare rock sides. And I occasionally got glimpes of the cliffs I was headed for, far upstream.

Finally I reached the junction with a smaller creek on my right, coming down from the cave. The bank was completely trashed by cattle.

The side creek drains a hidden basin, which opened before me as I walked up the creek. The water soon receded underground and I was making my way up a dry wash, surrounded by the eerie white skeletons of trees burned in the 2011 wildfire and green thickets of oak and juniper that had filled in afterward. And ahead, the cliffs, over 200 feet tall, under which I expected to find the cave.

Eventually my way up the wash was blocked by deadfall. The head of this basin consists of nothing but spectacular cliffs and rock formations, and would be a wonderful place to explore if it wasn’t so choked by fire debris and regrowth. But I noticed a narrow track – another cattle trail – up the bank to my right, heading toward the base of the cliff. And following it, I began finding the trash.

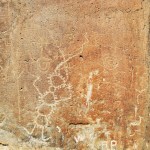

It was really old trash – the recent hikers hadn’t come this way, and nobody else but cows had been up here in many years, perhaps not since the 2011 wildfire. But there was literally a trail of trash leading through the brush to the cave itself, where faint prehistoric pictographs had been covered by someone’s huge red initials.

The ceiling was heavily blackened with soot – people had obviously camped in this cave for centuries, if not millenia. And some old hermit had lived here at one point – the rusted top of his cast-iron wood stove lay half-buried just outside.

I wasn’t up for a thorough search, but what I encountered right on the trail and on the floor of the cave included: three decomposed nylon day packs, a decomposed nylon fanny pack, various other decomposed nylon items that may have been gloves or climbing accessories, two decomposed hiking boots, a cooking grille, a bunch of tuna cans, and a pop bottle.

And of course, there was a deep layer of cowshit across the entrance.

It’d taken me four hours to reach the cave – a four-mile hike, half my day. So I knew I wouldn’t reach the rock formation above the main creek. But I should have enough time to explore a little farther up the main creek, to see how far I could get in a half hour.

The answer was, not far. I did reach the next tributary gulch, where I encountered a solitary bull. I didn’t want to risk irritating him, and it was time to turn back anyway.

On my difficult, dangerous way back, I wondered whether it would ever be possible to improve this trail and clean up all that trash. It’s far outside the designated federal wilderness – hence the cattle – so this area was obviously sacrificed in a compromise with the ranching and mining industries, decades ago. And now, limited trail maintenance efforts prioritize trails within the wilderness.

It’s only one beautiful canyon in a range of beautiful canyons. But cleaning up the trash wouldn’t be that hard. There was far too much for me to carry out that day, but three people could do it if prepared.

Logs and brush can always be cut, and tread could be improved, on the creek bank and upper slopes, but big obstacles in the creek bottom will always exist due to flooding. And hikers will always have to carefully pick their way up the narrows. But on my way back, I discovered historical bypasses that climb above the narrows – these could definitely be restored.

There will always be stretches where no trail is possible, where the route leads up long debris flows that get rearranged in floods. But the whole cairn situation could really be improved. Many existing cairns are decorative – something special to this canyon that I haven’t seen much elsewhere. But cairns exist in only about half the places where they’re most needed – at creek crossings, places where the route leaves a debris flow and climbs up a bank, and around major obstacles. That’s another easily solved problem.

A hiker could probably move 50% faster with those improvements, and be rewarded with the prehistoric cave and the spectacular cliffs and rock formations.

I was a little sorry to leave the narrows behind, and my way did get harder in the lower canyon. But I had plenty of time and was able to focus more on my surroundings.

Once past the cabin, I saw a couple of whitetail deer. Before that, I’d seen many, many birds and butterflies throughout the day, but they’d been too skittish to photograph.

Driving under the sycamores across the creek to the valley road, I stopped for a drink of water, and as I was sitting in the vehicle, an old bearded man came out to his gate across the road and stared at me. I waved, he waved and kept staring. It was the gate to what was apparently a big family compound with at least two houses, one of them huge. I was in kind of a hurry, so I just waved again, and drove off. But I regretted not being able to question him about his community. Of course, he just wanted to know what I’d been up to back there – hopefully not vandalizing his neighbors’ properties in this extremely remote, hidden valley.

March 19, 2023

Canyon of the Long Skinny Creature

After last week’s false spring, our weather got cold and wet again. I’d done a midweek hike on a muddy trail and wasn’t up for any more of that.

And after last week’s Arizona pictograph hike, I’d done some more research on the “high desert” area along the border, a large, remote region I’d previously ignored. There weren’t any trails there, but there were some buttes I could probably bushwhack, and by chance I learned about a canyon with petroglyphs. It would require an overland approach in unfamiliar terrain, and I couldn’t actually tell if the canyon itself was passable, but I’d give it a try.

I expected the petroglyph hike to be short, so afterward I hoped to drive north to the buttes and get some real mileage and elevation in.

There was frost on my windshield when I left the house – really unusual for this time of year. And our windy season starts in March – we were forecast to get gusts in the 40s.

The sky was mostly clear with high clouds. It took me an hour to reach the turnoff onto the first dirt road – as usual my topo map had it mislabeled, so I wasted 10 or 15 minutes looking for it. Once on the right road, I passed a Fish & Game truck, then found the next turn, onto a winding, high-clearance ranch road that turned out to be in terrible shape, with dozens of washouts. That road took me over a low rise, then down into the broad alluvial valley of our famous river. The road was so bad I averaged less than 15 mph.

Then I reached the final turn, onto a dirt track that hadn’t been driven in a year or more. It was even worse than the previous one – there were parts I could’ve walked faster than I drove. But I continued, through an old wire-and-branch gate that had almost dry-rotted apart, until I finally reached a dry wash where the track completely disappeared.

My topo map showed a couple of major tributaries approaching the canyon from this direction. I was hoping this dry wash was one of them, and sure enough, I immediately found the tracks of recent hikers. They’d come down the wash from much farther east – like the vast majority of urban hikers, they were probably driving a Subaru or some other low-clearance vehicle that couldn’t handle the track I drove.

I figured it would be a little over a mile to the main canyon. I was walking in deep, dry sand, which is no fun, but at this latitude and elevation, I was surrounded by familiar plants – honey mesquite, catclaw acacia, and best of all, really healthy creosote bush – so I almost felt like I was back home in the Mojave. I had to keep slowing down – my normal pace doesn’t work in sand.

This tributary, cut through alluvial deposits, finally reached a bedrock layer of conglomerate where it tightened and dropped through a slot. Around a few more bends and I was at the main canyon.

The main canyon started shallow and broad, but as it twisted back and forth it soon got deeper, and I reached a broad central area featuring old cottonwoods, living and dead. Water appeared on the surface.

Past there, it began to feel more like the canyons of Utah, with tilted strata rising from underground, water running over sculpted bedrock, and finally a slot canyon, where I had to climb down several short pouroffs.

Past the slot canyon, I carefully picked my way across a long, sculpted ledge and found myself at the edge of an overhang, looking down at a deep emerald pool.

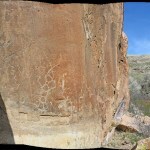

The ledge ended in a sort of ramp that I shuffled down on my butt. And turning to look at the pool, I discovered the first petroglyph panel, in a niche of a boulder overhanging the water.

Walking down the canyon from the pool, I immediately saw another petroglyph panel at the base of an outcrop on my right. To my left, high above the wash, I spotted a big white petroglyph. And straight ahead was the river, muddy and racing along in flood.

I walked toward the end of the wash, but soon got bogged down in mud. So I began climbing the left slope toward the petroglyph I’d seen above. The surface was a sort of treacherous shale.

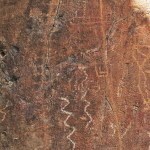

The first thing I noticed was that there were two layers of carvings, one ancient, patinated, and dim, and the other much more recent, in high-contrast white. Unfortunately I’d arrived at noon, and the sun was casting a shadow that divided the panel. So I ate lunch and waited for the shadow to move.

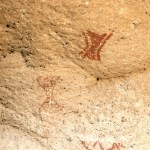

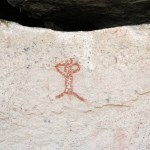

What I was most interested in was the left side of the main panel. There were two tall images in parallel – a sort of ladder or trunk with branches, and what looked like a long skinny lizard with the head of a bird wearing horns like a sheep. They were obviously designed together to convey a single message.

From my lofty perch, I watched hawks wheeling on thermals over the riparian corridor. This whole valley is a wildlife sanctuary and wilderness study area, and is known for its exceptional bird diversity. But the more time I spent up there, the more I noticed the lichen.

Finally I got the shadow and pictures I wanted, and made my way back down, to check out the smaller panel across the wash. It had the same two layers, likely separated by thousands of years. So-called “rock art” is mostly ignored by scientists, and relegated to amateurs, who divide it into regional and temporal styles. But indigenous people recognize it as writing, and the rock writing I’ve seen is a continuum spanning the West, sharing a common vocabulary.

A gale-force wind was blowing straight up the canyon as I started back. I had to lean into it.

The wind was a little less harsh when I turned off into the tributary wash. There, I began to pay more attention to the year’s first wildflowers.

When I finally reached the vehicle, I discovered I’d spent 3-1/2 hours on a 4-1/2 mile hike. It’d taken me an hour to drive 9 miles on that washed-out ranch road. So there was no time left for a hike in the buttes to the north. But I drove up there anyway, and found that my map again had the roads mislabeled, so I couldn’t find the road I needed.

I arrived home after being gone for 8 hours, most of which was driving. And as soon as I got out of the vehicle I could smell the creosote bushes, which had scraped the sides on that abandoned track. Best thing I’d smelled in months!

March 14, 2023

Hiking Through Time

I set out simply hoping to escape the snow in our local mountains – and ended up enduring hardship and danger in a remote, exotic landscape, to finally discover an ancient mystery.

City people think of mines as 19th century phenomena and copper as a 19th century commodity. But all the electronic and mechanical devices and machines we use are made of natural materials mined from holes in the ground that used to be natural habitat.

Electric cars use up to ten times the copper of conventional cars. Solar plants and wind farms consume massive amounts of copper. Mines and copper aren’t the past – they’re the future our colonial lifestyles and worship of progress have committed us to.

I live in a copper mining town – I can’t ignore or deny our impact on nature. It hurts me deeply to see these gaping wounds where wildlife and indigenous people once flourished, former heavens we’ve turned into toxic hells. 24-hour factories manned by dark-skinned laborers who are taught that they’re making life better for the rest of us. Hells we enlightened white professionals tend to avoid while fantasizing that our progressive lifestyles are saving nature.

As huge as our local mines are, they’re nothing compared to the ten-mile-long monstrosity over in Arizona. I was interested in trails in the mountains just north of the mine, but they were far enough away that I’d need places to eat and stay overnight after the hike, in or near the forbidding company town.

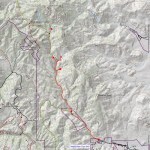

After weeks of sporadic research, I discovered a refurbished historic hotel in the quaint village below the mine town, reserved a room and put together some information on the closest of the trails. The topography of those mountains is incredibly complex – it’s not even a named mountain range, it’s just a confusing region of countless ridges and peaks, ranging from just below 4,000′ to just above 8,000′, rising between the valleys of a south-trending small river in the east and a south-trending large creek in the west.

A narrow, vertiginous paved highway leads north through the open-pit mine and up into the mountains, where it follows sinuous ridgelines for about another 50 miles to the base of the Mogollon Rim, finally climbing the Rim to the 9,000′ alpine plateau.

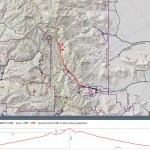

According to my topo map, the trail I wanted starts about 8 miles north of the mine, on a north-south ridgetop at 6,200′, surrounded by higher ridges and peaks. Trending generally westward, it first circles the head of a small north-south canyon then climbs to a high saddle on the next north-south ridge. This high saddle is the divide between two landscapes.

The first landscape is the north-trending corridor beginning with the mine and continuing up the highway. The second landscape, past the high saddle, appeared on the map as a long, broad valley descending westward between two east-west ridges.

Past the saddle, the trail appeared to descend this valley along the foot of its northern wall, through lower-elevation habitat I expected to consist mostly of exposed grass-and-shrublands. The entire trail was variously listed at 10-11 miles one-way, too long for an out-and-back day hike this far from home, so I planned to go only as far as conditions and time allowed – ideally 7 or 8 miles.

I usually avoid trails that start by descending and return by climbing, but beggars can’t be choosers. I do seek elevation gain, and while the map showed this trail descending from 6,200′ at its start to 4,200′ at its end, when I plotted it, the cumulative elevation gain turned out to be more than twice that. I would learn the reason for this soon enough.

I found little online information – this trail seemed seldom-used. I did find, in one old hiking trip report, mention of a prehistoric Native American pictograph site somewhere above that western segment of the trail below the east-west ridge, along with some vague, poorly shot photos. They didn’t clearly identify the location, which was both good for the site and bad for me, but they mentioned springs and black water piping left by a rancher in the vicinity.

Sunday’s sky was forecast to be mostly clear with scattered clouds and a high in the mid-60s. The drive took longer than expected, but in crossing the state line, I regained the hour I’d lost at home with daylight savings time.

As I drove through the mine, house-sized trucks operated all around the pits, so dwarfed by the scale of the mine I could hardly see them. Other than that, I encountered virtually no traffic, nor on the narrow, winding, crumbling highway with sheer drop-offs and no guard rails that climbs out of the mine canyon into the mountains. After pulling over briefly to check my map, I easily found the turnoff for the trail, a high-clearance 4wd dirt road. The map I’d brought showed the trail starting at the highway, but I decided to drive up the dirt road a ways instead.

The dirt road led to a ridgetop saddle with a big cleared parking area, where I found four pickup trucks with camper shells parked at random and 8-10 young people milling about with miscellaneous gear piled on the ground. Yikes! But their trucks were old and they were drably and cheaply dressed – not in the latest styles from REI – so I could tell they weren’t typical yuppie adrenaline seekers. And they were largely ignoring me, looking a little dazed like they’d just gotten up.

I parked and asked the nearest guy where they were from and what they were up to. He said they were near the end of a ten-day trip, mostly from Montana. They’d been in my hometown last week, and were planning a two-night backpack on this trail. He said he’d hiked it back in 2007 – but they all appeared to be in their early-to-mid twenties so he must’ve been about eight years old then. He mentioned the pictograph site and said it was right above a corral, with a black plastic water pipe running straight up to the site. That’s where they were heading and planning to camp.

As we were talking, one of the pickups drove away, back toward the highway. Perplexed, I thanked the young guy for the information, shouldered my pack, and headed off. It was chilly but sunny, so I tied my sweater around my waist, hoping the exercise and sun would keep me warm. I’d gathered from the old trip report that the trail began as a two-track mine road. Descending steeply into a narrow canyon through scrub and open pinyon-juniper-oak woodland, it was deeply eroded and blocked sporadically by boulders. The only tracks I found were from horses and a couple of hikers, from a week or more ago when the trail had been wet and muddy.

I began to realize that I’d misinterpreted distances on the topo map. I knew that in this first part of the trail the mine would remain visible on my southern horizon, but once I got past that high saddle it would be hidden and I would be in a new, wild, yet unseen world. Now, I began to realize that the high saddle was going to be much farther than I’d expected. This old road wound in and out of side drainages and forested habitat, traversing up and down steep grades, from which I couldn’t even glimpse the far ridge with the high saddle.

I was surprised to find Arizona cypresses on east-facing slopes. I have a couple of big ones in my backyard, but I’d never encountered them in the wild. Here, they were mixed in with pinyon, juniper, and oaks. From a distance, they looked much like firs or spruces, but at much lower elevation.

Eventually the road took me up over a low, rounded, exposed ridge, where a cold wind yanked my hat off. I was discouraged to realize I needed to drop into yet another deep side drainage before climbing toward the high ridge. I hadn’t noticed any of this up-and-down stuff on the map.

The old road ended at the bottom of the drainage, at a muddy, nearly dry stock pond and a low earthen dam. Below the dam I found a dilapidated trail sign pointing to an almost completely overgrown single track. This followed a trickle of water a few hundred yards to the edge of a cliff with fairly spectacular rock formations. From there, instead of climbing to the high saddle, the trail continued to descend, rounding an outlying shoulder where I found myself facing a dense forest across yet another narrow canyon. My high saddle was still hidden somewhere even farther above.

The farther I went, the steeper the climbs I faced. The next climb entered the forest, which turned out to be an almost pure stand of Arizona cypress. The grueling climb was only partly compensated by the botanical novelty. Disorienting, the cypresses felt like an alpine forest from three or four thousand feet higher – strange and mysterious. I saw the occasional pinyon or alligator juniper, but mostly just the stately cypresses, their branches densely interwoven.

Somewhere in that climb, the horse and hiker tracks ended and I seemed to be on virgin trail. By my watch I figured I’d gone a couple miles. I eventually climbed out of the forest and found myself facing east across a mile of intervening drainages to the cleared saddle where I’d parked. I could see my vehicle, but all the Montana pickup trucks seemed to be gone. Why had they given up on their trip?

The trail then curved to my right onto a south slope which was mostly scrub, facing the distant mine. Then, surprisingly, the trail began to descend again, rounding several more shoulders, still overlooking the mine to the south, before I finally spotted what must be the dividing ridge holding the high saddle.

This required yet another steep climb, but it was a huge relief to finally reach the little saddle which marked the divide between the “mine” side and the western backcountry I’d worked so hard to reach. It had taken me an hour and a half and more than three miles of steep up and down climbing.

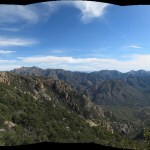

The trail past the saddle was as steep as anything I’d faced so far, and much rockier. But gaps in the forest began to reveal a new world of endless western views and, to my right, the south slope of a ridge banded with red and white cliffs and ledges.

I’d left the cypress forest behind and was now dropping from open pinyon-juniper-oak woodland onto shallower grassy slopes dotted with shrubs. The narrow track got fainter and more overgrown, but I was reassured by the periodic appearance of long-established cairns.

The temperature remained in the low 60s, and a cold wind was hitting these open slopes so I had to tie my hat down tight. But the sun kept me warm.

I’d completely misinterpreted the map on this side, too. I’d expected the trail to descend a long valley westward along the foot of a high east-west ridge. The high ridge was there on my right, but a seemingly endless series of drainages cut southward from it, dissecting the valley into a seemingly endless series of rounded humps and deep gullies. My trail would have to climb down into and up over them like a rollercoaster. I was still hoping to find the pictographs, but I couldn’t imagine where anyone would put a corral in that convoluted landscape.

At this elevation, both catclaw acacia and honey mesquite grew together along the trail, and before long my skin, shirt, and pants all bore numerous scratches.

Up and down I went, over and over again, on a nearly invisible trail lined with sharp embedded rocks that had me stumbling and cursing. At several points I had to stop and spend minutes scouting among the dense, dry grasses for the trail ahead. In a few spots with bare dirt atop low ridges, I found the tracks of a man in sneakers who’d walked this way during a wet period, more than a week ago. Apart from him, no one.

Finally I reached the rounded top of the highest intervening hump and faced a big side canyon that cut far into the high ridge on my right. I found it on my map – it would require another steep downclimb of several hundred feet, and another steep ascent on the other side. Great.

I figured I’d gone five miles so far and simply had no chance of reaching the corral – which was also marked on my map – or the pictograph site. It was a beautiful day and this was a spectacular landscape, but it’d been one of the hardest hikes I could remember.

However, I still had time, so I carefully descended the dangerous, rock-strewn trail to the dense riparian corridor in the canyon bottom, where I found a creek carrying clear, ice-cold snowmelt.

Unfortunately, the trail seemed to end at the creek. The only clue was an old sign pointing downstream to a spring – apparently the creek is normally dry. I followed that to where it ended at the bank of the creek. I crossed and saw a faint opening in the dense vegetation ahead, and shortly came to a tiny clearing where a barely discernable track switchbacked up the dark slope through the trees. Emerging from the riparian canopy, I found myself in what looked like a very steep, rock-filled erosional gully, but I kept climbing, and soon emerged on the familiar, overgrown, rocky, almost completely hidden single-track. A cold wind again threatened to take my hat, and I faced more rollercoaster ridges and steep climbs ahead.

The cairns had ended and I was left with only my routefinding skills. And past the big canyon, trail conditions deteriorated further, with both thorny catclaw and mesquite often blocking my way. With no hope of reaching the pictograph site, but with a little time still remaining before I had to turn back, I forged ahead as best I could. The rock “bluffs” above on my right were getting taller and more spectacular.

And after climbing up and down several more side drainages, I finally reached a deeper one where the trail really seemed to end. I explored a few options, but they all ended in catclaw thickets and piles of rocks. Suddenly, returning from one of these forays, I noticed something bright red in the distance, just above the trail I’d arrived on.

It turned out to be a jumble of plastic cord, and next to it was a loose pile of galvanized water pipe. Scouting around a little I also found some black plastic pipe.

No corral – not even the hint of level ground on this high slope – but could this be the way to the pictograph site? I had no more time left – but shouldn’t I at least make an effort to find the water pipe descending from the bluffs?

I returned to the bottom of the steep little gully. Above me, giant boulders blocked the drainage below the cliffs. I laboriously climbed a little ways up, getting more and more discouraged in the boulder-choked drainage. But then I saw the black water pipe, draped over a boulder above! This had to be it!

It was obviously going to be a brutal climb, and I was sure that if I continued, I’d be stuck trying to find my way back to the vehicle in the dark. But I had a headlamp, and the last hour and a half of trail should be easy to follow. So I continued.

Having started in the gully, which was getting deeper, with sheer walls, I had to do some really dangerous moves to follow the pipe out of it onto the 45 degree, catclaw-choked slope above. From there, it was a long, slow, dangerous scramble toward the foot of the cliff, which loomed at least 150′ tall. But I was now absolutely sure this was the place – it matched what I’d read in the old hikers’ trip report, and I could tell there was an overhang and a ledge up there under the cliff.

Interestingly, although the pipe had clearly been abandoned, and surplus sections of it littered the slope, when I came to a tee fitting with shutoff valves, water was leaking out abundantly. It was still connected to the source, somewhere above.

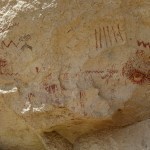

Emerging onto the ledge below the bluff, I immediately spotted the pictographs, and the cave behind them, with its two seeps. The previous hikers had called it an Anasazi site, showing typical ignorance. But as I approached these signs from the deep past, my whole body registered its presence in a sacred place, starting with the tingling in my spine. I hadn’t felt like this since my last trip to Utah.

Canyon wrens cried and cliff swallows wheeled above as I explored the cave and the long ledge. It was blanketed with old cowpies and strewn with ranchers’ debris, but the rock writing was undisturbed. This was the most remote and little-known major site I’d ever found.

The Forest Service map I carried showed the corral nearly a mile west of here, in a fairly level spot. The 16-year-old memories of the Montana folks had understandably been a little rusty. But I was more curious about the water pipe, and the seeps under the cliff. This is normally a very dry area – the creeks and springs were running now after our wet winter, but would there really be a water source here, high on this slope, year-around? That would certainly explain the pictographs as well as the water pipe, and make this a precious site in more ways than one.

At this point, I no longer cared that I was late. But I was facing a really dangerous descent from the ledge, followed by a long climb to the high saddle, with countless brutal ups and downs before and after – hence the over 4,000′ cumulative elevation gain. My first job was to avoid injury on the way back down to the trail.

Taking it slow, I made it down safely, and vowed to take it easy on the entire return. But my left foot condition had been triggered for the first time in almost a year. I’d switched to winter boots in June when our monsoon started early, and when monsoon transitioned to snows I’d kept wearing them until now. Those boots have the stiffest available soles, but today I’d reverted to my old favorites, Goretex boots with slightly more flexible soles, and my foot was not happy. My knee was complaining, too.

If I took a pain pill, I would dehydrate faster, and with the arduous climbing in warmer temps, I was already running low on water. So when I reached the creek in the big side canyon, I stopped to fill and zap a liter bottle with my Steri-Pen. It was cold and delicious, and I popped a pain pill for my knee and foot.

After the steep climb out of that canyon onto the next shoulder, as I started down into the next drainage, I was surprised by voices. A twenty-something girl, wearing a bundle of fine rings through her nasal septum, appeared out of the scrub, followed by three tall young guys. As we talked, I learned they were part of the group with the pickup trucks. They said their other friends had had to leave early. I started raving about the pictograph site, but the girl said she’d also been here in 2007. I found myself liking them more and more for their cheap, well-worn gear and outfits. They were taking ten-day camping trips instead of competing for high-paying desk jobs. But I remained mystified about what they’d been doing all day, and why they’d gotten such a late start.

I continued and got lost in a badly overgrown area, wasting about 20 minutes scouting in several directions before relocating the trail. The final climb out of this remote backcountry to the high saddle seemed endless.

Once past the saddle, although it would still be a rollercoaster with brutal grades, on average it would be downhill – at least until the final climb to the parking area. I was mostly in shadow now and had to pull on my sweater. And those cypress forests were downright gloomy.

Most of the trees were less than 20 years old – many tall snags stood among them, but they hadn’t been killed by fire, so their deaths remained a mystery. The new trees and seedlings formed impenetrable thickets.

In the broad drainage before the final climb, another old two-track takes off north. I assumed it led to abandoned mine works. But checking the map again that night, I saw that it has its own Forest Service trail name and number – the Crystal Cave trail. It’s only a tenth of a mile long. But I couldn’t find any information on it online. More intrigue.

I’d hiked through time, from our future of unsustainably mining Paradise and turning it into a toxic Hell, to the not-so-distant antiquity of sustainable indigenous culture. And back again.

This was more elevation than I’d gained on any hike since last October, before the winter snowstorms. Preparing to return to the mine town to look for dinner and my hotel room, I wasn’t sure whether I envied the backpackers, or should consider camping on these Arizona day hikes instead of sleeping indoors.

The fact is, whereas city people plan backpacking trips once or twice a year, and do the rest of their hiking in crowded parks near town, I get to do these remote day hikes every Sunday. Turning them into backpacks would subtract several days a week from the work I desperately need to finish at home, and camping overnight would reduce the time left for hiking – I’d have to return earlier to set up camp and cook. Although I do envy backpackers when I meet them, I get much more wilderness hiking in, week to week – and I still do longer camping and backpacking trips once or twice a year.

The sun set as I was driving back through the mine. I turned off into the company town for the first time, found the sole restaurant, where I orded dinner to go, and grabbed beer at the nearby supermarket. Architecture and infrastructure were functional, bare-bones, but well-maintained.

Then, in full dark, I located my hotel in the old village below. I was exhausted, sore, and starving. The little building, which is not staffed, and in which I was apparently the only registered guest, was dark and locked up for the night. I had the code but couldn’t figure out how to operate the coded entry, so I had to call and wait for the manager to show up and let me in.

After dinner and a shower, I was still so excited about the hike, I finally had to take a sleeping pill, sometime long after midnight.

March 6, 2023

Return to the Rocks

I was beyond stir-crazy. Hiking was the main thing that kept me healthy in body and mind – it relieves stress, lowers blood pressure, manages pain and enhances mobility – but deteriorating trail conditions had forced me to give it up two weeks ago. Since then, we’d had several more snowfalls, and I’d become virtually sedentary.

Local trails were still out of the question, with either deep snow, deep mud, or creek crossings flooded by snowmelt. Besides, I needed to get away from the obligations, the worries and unfinished projects weighing me down at home, even if only for a night.

But I expected to find the same conditions everywhere in our region. Sunday morning arrived and I still hadn’t made a decision before my usual 8 am departure time. I followed the opening race of the Formula 1 season, which would end about 9:30 am, and finally decided to drive over to Arizona to the range of canyons. Conditions would be the same there, but with less than a full day left, I could busy myself with short, boring low-elevation hikes, enjoy dinner at the cafe, and get a room for the night. If nothing else, it would get me out of the house.

I arrived at noon, leaving me five-plus hours to hike and reach the cafe before closing. In normal conditions, that would give me plenty of time to take the nine-mile out-and-back peak trail at the mouth of the basin. But it ends in traverses and switchbacks across a steep north slope above 7,000′, topping out at 8,000′, and I expected north slopes at those elevations to carry well over a foot of snow now.

I’ve done that hike twice before, but I normally avoid it – it’s the most popular hike in the range, too short for a full-day hike, and it falls completely outside the wilderness area, so there’s less chance of encountering wildlife. But it is spectacular, and it would offer my best option for gaining some decent elevation in the time I had.

It was a sunny, calm day with high, wispy clouds, and the temperature surprised me by being in the mid-70s when I got out of my vehicle at the trailhead. It’d been an unusually long, cold winter, and I couldn’t remember feeling so comfortable outdoors since last September! Expectedly, there were three other vehicles there already.

I unbuttoned my shirt, and as soon as I climbed out of the lush riparian zone onto the open, grassy slope, the temperature seemed to rise into the mid-80s. Surrounded by one of the most spectacular landscapes in the Southwest, with layered red and white cliffs and ramparts of towering spires, I stopped to stretch and tighten my boots. And a tiny older man in a drab “socialist worker” outfit – even shorter than me! – passed, running down the trail, carrying no gear, not even a water bottle.

A little farther up, I met an older couple resting in the shade of a juniper. They were on their way down, and said they’d only made it to the prominent “Trail” sign up on the shoulder of the ridge. The woman said “That’s halfway, right?” but I pointed out it was considerably less than that, and the man looked away disgustedly.

Despite its popularity, this is one of the two steepest trails in the entire range, with an average grade of 13% – so although many struggle up the first mile or so, only the truly athletic achieve the 3,200′ ascent to the peak.

It proceeds in two major segments: the climb across the northeast slope, out of the “gateway” basin and around the shoulder of the ridge, followed by the traverse and climb of the north slope. The first segment gets enough sun to be both snow-free and dry, so I made good time there. My body felt healthier – back in the conditions where it thrives – and my spirit rose with the elevation and the unfolding views across the landscape.

1,200′ up, I rounded the shoulder into the broad hollow of the north slope, a complex circling wall of layered red rimrock cliffs and towering spires, bisected by a precipitous ravine. Whereas my view on the first segment had been eastward past the range’s gateway, I now had a view across the northwest ridges of the range, all the way to the snow-draped crest of another range I’d last climbed in December, 70 miles away in the clear air.

I soon met the next party of hikers, a couple a little younger than me. I was curious about how much snow they’d found ahead – I couldn’t see much from this vantage point, but it might be hidden under forest, and snow settles deeper on trails than on the surrounding slopes.

The man said they’d turned back because the trail surface was too slippery with ice and wet snow. I asked if they’d reached the switchbacks – meaning the final switchbacks to the peak – and the man said they’d only made it halfway up. They were both using trekking poles, so I figured the trail must be pretty bad. But I had to find out for myself.

Shortly after I passed them I reached the first set of switchbacks, and sure enough, they were slippery with wet, shallow snow – but nothing I couldn’t handle. I just had to adjust my gait, using the edges of my boots to chop holds in the slush. The couple’s tracks turned back halfway up, so I realized we’d misunderstood each other. There are three sets of switchbacks – they’d stopped at the lowest of the three. Past that point, there was only one set of tracks going forward – also from today – two people, both bigger than me, with a dog.

This first set of switchbacks leads to the first big red outcrop – the face rock. Passing below that, you enter the confines of the ravine. Dwarfed by towering outcrops on all sides, you reach the second set of switchbacks, where the trail condition was about the same. These take you high enough to cross the ravine, through a narrow riparian forest, past which you begin the long traverse of the main north slope.

That’s where conditions got trickier. There were still occasional dry patches, but I was now above 7,000′, and the snow was up to six inches deep, fresh and soft. And before long, I reached a narrow spot where one of the hikers preceding me had slipped off the trail and slid straight down the steep slope below. They’d fallen at least fifteen feet, and maybe much more – I couldn’t tell with bushes blocking the view. The slope itself drops continuously two or three hundred feet into a ravine, with only spindly shrubs to break your slide – pretty scary!

It was a good warning for me to proceed with utmost caution. But their tracks resumed past the narrow spot – I figured they must be young people who wouldn’t let a fall scare them. And whereas their tracks showed that they were hiking in sneakers or cheap lightweight boots, I was wearing my serious winter boots, with good traction and sharp edges to chop holds in the snow.

The traverse winds westward in and out of drainages, eventually entering mixed conifer forest. I always look forward to the tall, shaggy firs – an island of alpine habitat confined to the top of the steep north slope of this relatively low peak. But the shade of the forest meant that the west end of the traverse lay under a continuous blanket of still-fresh snow, six inches or more deep. Here, the temperature had dropped from the 80s to the high 50’s, so I pulled my sweater back on.

At its far west end, the trail swings back to climb through more spectacular rock outcrops, beginning the final set of a dozen switchbacks that end on the summit ridge. These switchbacks held the deepest snow, and this was where I expected the most difficulty. But I was already exercising plenty of caution, and reached the crest with what I thought was enough time remaining for the descent.

On this last climb to the crest, you’re getting glimpses through the forest and between the rock outcrops to the landscape 3,000′-4,000′ below, and it’s a truly impressive and sobering preview of how high you’ve actually climbed in the past three hours. But it gets both better and worse.

This is a freestanding mountain, surrounded by low basins which are themselves ringed by more distant ridges. So on the crest, you’re on a precipitous island with a drop of 2,000′ to 3,000′ vertical feet on all sides. The final switchback leads to a tiny exposed saddle on a knife-edge ridge, which was sun-drenched now, hence blissfully snow-free.

It’s only a short distance up the ridge through low forest to the time-worn, lichen-encrusted cast-concrete stairs that take you to the peak and the foundation of the old fire lookout. These crude stairs violate every safety code you can imagine, with tall risers and shallow treads. They’re like a miniature version of the terrifying stairs up the cliff in Lord of the Rings. Even in dry conditions the climb to the top is more like the crux move of a technical climb up a crack in a rock wall. There’s no railing on the lower, steeper flight, and a fall would dash you onto the rock ledge below, and possibly over it down the north slope.

But today the lower steps were packed with slippery snow, so I made use of every available handhold – the brush and boulders at my left, the wet but snow-free edges of the steps above – and basically crawled up on all fours, trying not to think about the coming descent.

The upper flight of stairs, fully exposed to the sun, was completely snow-free and dry, but since it overhangs a cliff, it has a galvanized pipe handrail – something the lower flight could really use.

Summiting the stairs and stepping into the concrete enclosure, with its 360 degree view across the entire northern range, is one of the most dramatic moments imaginable. And as I was taking it in, and starting to take pictures, I heard a whoop from a neighboring peak, about 300 yards behind me to the east. It was the other hikers. I could make out a tall young man, but his partner was sitting behind a shrub. I waved back, and savored the views for about ten minutes, before firmly grabbing the handrail and stepping slowly down the vertiginous stairs, one at a time, nothing but a pipe railing between me and a 2,500′ vertical drop on my right. My time was getting short and I’d have to hurry down the dry stretches of trail.

I somehow made it safely down the tight, steep snow-packed lower steps, once again using my boot edges and every handhold possible. Then from there onto the forested upper switchbacks, where I had my one and only fall of the day at the best possible spot, in deep, fresh powder.

Just as I approached the lowest of the upper switchbacks, I heard another whoop from above. The young hikers were beginning their descent, and I figured if they were whooping spontaneously it was probably two guys, not a couple.

I was in shadow for almost the entire descent, and running down the dry stretches took its toll on my knees, so I was in quite a bit of pain even before I rounded the shoulder onto the lower segment of the trail. But what a beautiful hike for a short day!

Body and mind had been starved for this – it felt like the hiatus had been much longer than two weeks. I actually hadn’t been able to get this much elevation – over 3,000′ – in any hike during the past two months. Let alone all that beautiful exposed rock – the hikes near town run through monotonous forest. And the fact that I was able to reach 8,000′ after all the snow we’d had was encouraging. Maybe there are more trails accessible now than I thought?

Arriving at the cafe, I saw the full moon rising in the west, and realized I’d returned exactly a lunar month after my last visit. And thankfully, my vision remained clear.

Healthy Addiction

I was beyond stir-crazy. I’d given up on hiking two weeks ago after encountering snow a foot deep on a trail that was my last resort for winter hiking. Since then, we’d had several more snowfalls, and I’d become virtually sedentary. Hiking is truly an addiction, and it just goes to show that not all addictions are unhealthy. Both my physical and mental health had suffered from not being able to do it.

Local trails were still out of the question, with either deep snow, deep mud, or creek crossings flooded by snowmelt. And I badly needed to just get away.

But I expected to find the same conditions everywhere. Sunday morning arrived and I still hadn’t made a decision before my usual 8 am departure time. I followed the first race of the Formula 1 season, which would end about 9:30 am, and finally decided to drive over to Arizona to the range of canyons. Conditions would be the same there, but with less than a full day left, I could busy myself with short, boring low-elevation hikes, enjoy dinner at the cafe, and get a room for the night. If nothing else, it would get me out of the house.

I arrived at noon, leaving me five-plus hours to hike and reach the cafe before closing. In normal conditions, that would give me plenty of time to take the nine-mile out-and-back peak trail at the mouth of the basin. But it ends in traverses and switchbacks across a steep north slope above 7,000′, topping out at 8,000′, and I expected north slopes at those elevations to carry well over a foot of snow now.

I’ve done that hike twice before, but I normally avoid it – it’s the most popular hike in the range, too short for a full-day hike, and it falls completely outside the wilderness area. But it is spectacular, and it would offer my best option for gaining some decent elevation in the time I had.

It was a sunny, calm day with high, wispy clouds, and the temperature surprised me by being in the mid-70s when I got out of my vehicle at the trailhead. It’d been an unusually long, cold winter, and I couldn’t remember feeling so comfortable outdoors since last September! Expectedly, there were three other vehicles there already.

I unbuttoned my shirt, and as soon as I climbed out of the lush riparian zone onto the open, grassy slope, the temperature seemed to rise into the mid-80s. I stopped to stretch and tighten my boots, and a tiny older man in drab clothing – even shorter than me! – passed, running down the trail, carrying no gear, not even a water bottle.

A little farther up, I met an older couple resting in the shade of a juniper. They were on their way down, and said they’d only made it to the prominent “Trail” sign up on the shoulder of the ridge. The woman said “That’s halfway, right?” but I pointed out it was considerably less than that, and the man looked away disgustedly.

This trail proceeds in two major segments: the climb across the northeast slope, out of the “gateway” basin and around the shoulder of the ridge, followed by the traverse and climb of the north slope. The northeast slope gets enough sun to be both snow-free and dry, so I made good time on that first segment.

I met the next party of hikers shortly after rounding the shoulder into the broad hollow of the north slope, which is lined with spectacular rock outcrops. It was a couple a little younger than me. I was curious about how much snow they’d found ahead – I couldn’t see much from this vantage point, but much of the north slope is forested and snow is always deeper on trails.

The man said they’d turned back because the trail surface was too slippery with ice and wet snow. I asked if they’d reached the switchbacks – meaning the final switchbacks to the peak – and the man said they’d only made it halfway up the switchbacks. They were both using trekking poles, so I figured the trail must be pretty bad. But I had to find out for myself.

Shortly after I passed them I reached the first set of switchbacks, and sure enough, they were slippery with wet, shallow snow, but nothing I couldn’t easily handle, even without trekking poles. Their tracks stopped halfway up, so I realized we’d misunderstood each other. There are three sets of switchbacks – they’d stopped at the lowest of the three. From that point, there was only one set of tracks going forward – also from today – two people, both bigger than me, with a dog.

This first set of switchbacks leads to the first big rock outcrop – the face rock – then once past that, you reach the second set of switchbacks, where the trail condition was about the same. Then the trail crosses a forested drainage and begins a long traverse of the main north slope.

That’s where conditions got trickier. There were still occasional dry patches, but I was now above 7,000′, and the snow was up to six inches deep. And before long, I reached a narrow spot where one of the hikers preceding me had slipped off the trail and gone straight down the steep slope below. They’d slid at least fifteen feet, and maybe much more – I couldn’t tell with bushes blocking the view. The slope itself drops continuously two or three hundred feet into a ravine, with only spindly shrubs to break your slide – pretty scary!

It was a good warning for me to proceed with utmost caution. But their tracks resumed past the narrow spot – I figured they must be young people who wouldn’t let a fall scare them. And whereas their tracks showed that they were hiking in sneakers or cheap lightweight boots, I was wearing my serious winter boots, with maximum traction.

At the west end of the long traverse, the trail is completely forested, under tall pines and firs, and here it was almost all under at least six inches of still-fresh snow. The temperature had dropped from the 80s to the high 50’s on this shaded slope, so I pulled my sweater back on.

The trail swings back to climb through more spectacular rock outcrops, beginning the final set of a dozen switchbacks ending on the summit ridge. This was where I expected the most difficulty, but I was already exercising plenty of caution and reached the crest with what I thought was plenty of time.

It’s only a short distance up the knife-edge ridge to the cast-concrete stairs that take you to the peak and the foundation of the old fire lookout. But the first flight of stairs is shaded and the risers are tall, with shallow treads. Most steps were covered with slippery packed snow, and a fall would end in injury at the very least, so I made use of every available handhold.

As always, the view from the top was glorious! And as I was starting to take pictures, I heard a whoop from the neighboring peak, about 300 yards to the east. It was the other hikers. I could see a tall young man but his partner was sitting behind a shrub. I waved back, and savored the 360 degree views for a few minutes before returning down the stairs. My time was getting short and I’d have to hurry down the dry stretches of trail.

On my way down, just as I approached the lowest of the upper switchbacks, I heard another whoop from above. The other hikers were returning, and I figured if they were whooping spontaneously it was probably two guys, not a couple. Descending those switchbacks in deep, fresh powder was where I had my one and only fall of the day.

I was in shadow for almost the entire return, and running down the dry stretches took its toll on my knees, so I was in quite a bit of pain by the time I reached the final descent to the trailhead. But what a beautiful hike for a short day! I hadn’t been able to get this much elevation – over 3,000′ – in any hike during the past two months. And the fact that I was able to reach 8,000′ after all the snow we’d had was encouraging. Maybe there are more trails accessible now than I thought?

Arriving at the cafe, I saw the full moon rising in the west, and realized I’d returned exactly a lunar month after my last visit. And thankfully, my vision remained clear.

February 19, 2023

The Last Resort

I was finally out of options. We’d had more snow in the past week, and more freezing weather. Rain was forecast for this Sunday, and more snow in the coming week.

There was literally only one hike on my list that might still be relatively free of flooded creeks, deep snow, and mud. I’d left it for last because the trail meanders through rolling mid-elevation pinyon-juniper-oak woodland just south of town, crisscrossed by ranch roads and grazed by cattle.

It was warmer in the morning – in the 40s – but I layered up with all my rain gear, and a light rain began as I headed off the paved highway toward the low mountains.

This would start like one of my regular midweek hikes – a route that’s one of my secrets, known to few others. I would take an unmaintained, high-clearance dirt forest road up a plateau mostly deforested by firewood cutters, leaving my vehicle in a little surviving stand of Emory oaks. From there I would walk up the deeply eroded road to where it dead-ends at the foot of a low peak, and from there I would take a short spur trail to where a seldom-used segment of the national trail skirts the base of the peak on its way north. I intended to follow the trail north for 7 or 8 miles.

But as soon as the dirt road entered the woodland, I unexpectedly found it under 4 to 6 inches of snow. Nobody had been up here, either on foot or by vehicle. The road climbs, and the snow got deeper.

The spur trail was doable, but when I reached the national trail my boots sank into snow over a foot deep. I hadn’t brought my gaiters, but even if I had, I was fed up with hiking through snow at this point. I made it about another hundred yards, but it was still getting deeper so I gave up, after only a mile and a quarter of hiking.

Why hadn’t I anticipated this? When I got home I realized that when choosing a hike, I’d glanced at the wrong line item on my list of routes. I thought this route topped out at 6,500′, which should’ve been snow-free, but that traverse across the base of the peak was actually 7,300′, and that additional 800′ made all the difference.

The result is that I now have no options left. This might be my last hike in a while!

After all, there’s no natural law that says humans should have access to nature at all times.

February 14, 2023

Valentine’s Anniversary

Exactly thirty years ago I had the best Valentine’s day ever.

We’d fallen madly in love a year and a half earlier, and had just reunited after a brief crisis and a few weeks’ separation.

Over the winter holidays, I’d helped her pick out a blue satin party dress. And for Valentine’s Day I gave her a dozen red roses. I know, conventional, but after the last few weeks, I wasn’t taking any chances! She set them on her side of our bed in her apartment on Grand Avenue in Oakland’s old Adams Point neighborhood, a block from Lake Merritt.

We both had the day off, and we packed our evening clothes into my Geo Tracker, and dressed for a day outdoors. We drove north through Berkeley and Richmond to the Richmond Bridge, and from there to Tiburon, where we parked and rode the ferry across the Raccoon Strait to Angel Island. It was a cool, blustery, but sunny day.

We rented mountain bikes at the landing on the island, and spent the day riding over and around the hills together.

In late afternoon we caught the return ferry to Tiburon, where we changed clothes in the Tracker – her satin dress rustling in the back seat.

Guaymas, the Bay Area’s fancy Mexican restaurant, was right next to the ferry terminal and parking lot, and I’d made a reservation. We chose a table on the outside deck overlooking the Bay, and were seated as the sun began to set.

After our drinks were delivered, the mariachis made a beeline for our table. My partner was Mexican-American, and she requested “Sabor a Mi”.

Our dinner was fabulous as usual.

We drove back to Oakland.

All I’ll say about Valentine’s night is that it literally couldn’t have been better.

February 13, 2023

Boggy Day in Horse Country

There was a hike on my list that I’d been avoiding, up in the heart of the wilderness, where elevations are moderate and snow wouldn’t be as deep. It didn’t seem to cross any major creeks. But it started from a famous corral, so I assumed it would see a lot of equestrian use. The day was forecast to be warmer, so I could expect mud, churned up by the horses. And worst of all, it seemed to be in the zone of the dreaded volcanic cobbles, which make walking extra hard.

I didn’t expect to find anything spectacular along the way. And yet another disadvantage is the drive – an hour and a half on a really scary mountain road, half of which has no centerline, so people tend to drive in the middle, even around blind curves. But I got an early start, and only encountered a couple other vehicles in 45 miles.

The corral is just downstream from the famous cliff dwellings, ground zero for tourism. There was a late-model city SUV at the trailhead, and a young guy was studying the info kiosk. I wished him a good morning but he ignored me – typical city behavior. By the time I set out, he was a couple hundred yards up the trail.

The trails in the heart of the wilderness either follow the forks of the river, or climb ridges. This was a ridge trail, recently cleared, which I hoped to follow to an 8,133′ peak, eight miles away.

It was freezing when I set out. I was catching up with the young guy within the first half mile, but that’s when I stop to stretch and tighten my boots, so I didn’t actually pass him until ten minutes later. He was already descending – it looked like he’d just been trying to find a cell phone signal. This time he managed to return my greeting.

The first half of the trail was in really good shape, and dry enough to avoid mud, so I made really good time. I’d expected this to be a popular trail, and the dirt showed a mixture of boot and horseshoe prints.

Continuing up the ridge past the first fork, the trail rises from the open pinyon-juniper-oak woodland into the ponderosa pine zone, then descends 300 feet into the canyon of a creek. I’d overlooked this on the map, and was surprised to find one of the biggest creeks in the range, in full snowmelt flood. It took me fifteen minutes to find a place downstream where I could cross on a log and a series of big rocks.

Past the creek, the day’s hike began to fall apart. I’d reached the zone of volcanic cobbles – a geological discontinuity – and from here on, it was rocks and mud churned by horses’ hooves.

It was a long, steep climb up another ridge. The equestrians had almost completely chewed up the trail, but I occasionally spotted a bootprint or two the horses hadn’t stepped on. It appeared that a man and a woman, probably backpackers, had toiled up the mud of this trail within the past month.

Fortunately no patches of snow yet, and the dirt was mostly still frozen, but the hike had gotten much slower. It was warm in the sun, so I took off my sweater, but wind was rising out of the west, and banks of clouds soon drifted over, so I had to pull the sweater back on, only to overheat fifteen minutes later. Eventually the trail dropped into the canyon of yet another stream – I hadn’t anticipated this either – but this one was smaller and easier to cross.

It was sweater weather again in that narrow, shaded canyon. And on the other side, a very steep north slope, the snow began – and under it, ice from successive melting and freezing, which made the climb really hazardous. I’d been assuming I wouldn’t hit serious snow until the final ascent of the peak, but when I reached the gentle slope atop the ridge, it turned out to be just high enough to hold some big, deep patches. And the snow was melting into the trail, which had already been churned up by the equestrians, so it was now a rock-filled bog.

I had to go off trail to avoid the mud, but off the trail, I was lurching and stumbling on the volcanic cobbles, many of which were hidden under tussocks of dried grass. There was enough forest around me that I had no view out and couldn’t see the peak I was aiming for, so I had no idea how much farther it was. This was turning into a truly miserable hike, and eventually I gave up.

Surprisingly, the backpackers’ tracks continued. I didn’t envy them a bit – where they’d walked in the trail, their boots had sunk in the mud several inches. They couldn’t have been having much fun, but as I’ve remarked before, despite its exalted reputation, this wilderness can be a truly nasty place for humans, and is getting worse due to wildfires and climate change.

I still had plenty of time, so on my return, I could pay more attention to my footing on the rough, pitted, boggy ground. It’s a miracle I haven’t sprained an ankle on this kind of surface. I swore never to take this trail again, even in the dry season.

It’s ironic and maddening, because the Forest Service has accepted that equestrians are the only group able to do regular trail maintenance at this point. The horse people see it as good PR, and they’re apparently encouraging increased horse traffic, which in muddy conditions renders trails almost useless for hikers. It’s a whole new regime, and I just need to plan around it.

It was a huge relief to finally cross the first creek and reach the easy first half of the trail. And when I got within 2 miles of the trailhead, I began to see more recent footprints – several people had gone a short distance up the trail while I was struggling up that distant boggy ridge.

In the end, I’d hiked 12.6 miles and climbed 2,300′ – the most I’d managed in the past month, but way below my long-term average. And on the drive home, I encountered vehicle after vehicle speeding on the mountain road, threatening to force me off the pavement as they barreled recklessly around blind curves – including a guy in a huge pickup towing a big trailer, two feet over my side of the centerline, heading straight at me.

The heart of the wilderness is where all the tourists go, and as far as I’m concerned they can keep it.

February 6, 2023

Canyon of Confusion

After weeks of health issues, deep snow in the high mountains, and boring local recovery hikes, I’d really been yearning to return to Arizona for a change of scenery. So I spent a few hours on Saturday in deep online research, trying to pinpoint an interesting low-elevation trail within my 2-hour-drive radius that would also be near the cafe and motel, so I wouldn’t have to drive the deer-infested highway home after dark.

There turned out to be only one trail that met my criteria, but relevant information was sparse and contradictory. The authoritative, detailed trail guide I normally rely on says it was only partially surveyed more than a decade ago and is in “terrible” condition, but the official trail map provided at the ranger station, updated in 2018, shows it as a major trail suitable for “Hiker/Horse/Mountain Bike”. And mapping websites show it as part of a national route used by through hikers, like the Pacific Crest Trail.

To further confuse the issue, the access road goes through a remote settlement which Wikipedia and other history sites call a ghost town, but satellite views show a sizable farm and many occupied, well-maintained residences. It’s in a part of the range I’d always wanted to explore. If it turned out to be a bust, I could always drive to the more familiar area and do a shorter hike in the time remaining.