Max Carmichael's Blog, page 20

January 3, 2022

Someone Else’s Playground

I have to start this Dispatch with several caveats.

First off, this was one of the most punishing and least rewarding hikes I’ve ever done.

Second, the pictures don’t really show what made it miserable. I had a friend – a young coder in the tech industry – who once told me that for his generation, if I didn’t get any pictures, whatever I was talking about simply didn’t happen. Most of my friends are urban professionals who would be really annoyed by much of what I experienced on this hike. Hence they’ve arranged their lives so they never encounter these kinds of people and their lifestyle, and may have a hard time imagining it.

Third, the title of this Dispatch was inspired by a song by my long-lost lover, bandmate, and loftmate, Francesca. She was my original partner in the Terra Incognita loft in San Francisco. Whereas we were temporarily together when we moved in, her “true love” was a classmate at CalArts, just north of Los Angeles. A few months after we moved in and recruited other artists and musicians, I met and fell in love with a student at the San Francisco Art Institute. At the same time, Francesca’s long-distance boyfriend dumped her, and her father cut off her allowance. Since the wheel of fortune seemed to be favoring me and punishing her, she started lashing out at me in various ways, and wrote “Someone Else’s Pocket” to express her feelings of helplessness in an environment where I was the authority figure. Ironically, she had to rely on me to put her lyrics to music.

We’d had a couple inches of snow in town yesterday, which partly melted in the afternoon. Since there would’ve been much more in the mountains, and snow always significantly limits my winter hiking choices, I’d made a short list of possible lower-elevation hikes. Sunday was forecast to be the coldest day we’ve had in many years, and I wasn’t even sure if it was a good idea to be hiking in such conditions. When I got up, it was 15 degrees outside and perfectly still under a crystal clear sky.

At the top of my short list was an unfamiliar trail in the heart of the wilderness due north of town. That trail stays below 8,000′, so I was hoping the snow there would be manageable. The trailhead can normally be accessed from town in about an hour’s drive, by two different paved highways. The longer route tops out at 6,500′, but the shorter, more direct route reaches 7,500′.

But after packing for the hike, I discovered that the door locks on both sides of my vehicle were frozen. We’d had high winds all day yesterday, and the snow had been preceded by rain – apparently water had blown into the locks and frozen. I didn’t have a blow drier, a torch, or anything I could use to warm the locks from the outside.

I was able to unlock and open the rear hatch, so I crawled through the vehicle, and found the inner door locks wouldn’t move, either. But since the two back seat doors have no external lock, I was able to unlock and open them from the inside. Should I simply crawl over the front seats and drive it anyway, accepting that the front doors wouldn’t work and I’d have to crawl in and out through the back? What if I had an accident on the icy/snowy roads, and ended up in a ditch? I’d have to hope I could crawl over the seats and get out that way. I hated to take the risk, but I equally hated to give up and stay at home.

For some reason, as I was driving across town, I decided to take the shorter, higher route. I suppose I wanted to test the abilities of my 4WD Sidekick and its expensive all-terrain tires. The snow got progressively deeper as the highway climbed to its first 7,000′ crest, and it had been plowed just wide enough for two vehicles to pass. I drove slowly and switched to 4WD when I saw the first patch of ice on the road.

There was literally no one else traveling until I reached the twistiest part through the dark forested mountains and suddenly saw a sheriff’s vehicle approaching me from around a blind turn. I lightly tapped the brakes and immediately began to slide sideways, narrowly missing the big SUV. That showed me how little grip I was going to have, so I slowed down even more and stopped using the brakes, using the accelerator and gear shift instead to control my speed.

I was encouraged to find clear stretches of asphalt where the road dipped below 7,000′ in the dark, narrow canyon, but at the end, where the road began winding and climbing steeply again, it was still plowed wide enough for two vehicles, but the pavement was entirely covered with frozen snow and ice. I kept going slowly and carefully for about a mile, but before reaching the highest point of the road, the plowed surface suddenly ended, with only a single pair of tire ruts continuing. The snow here was over a foot deep. If I encountered another vehicle I’d have to drive off into the deep snow, and my vehicle only has about 9 inches of ground clearance. I had to back up to the nearest bend, where there was just barely enough room to turn around.

When I reached the sharp turn at the canyon bottom, where a dirt forest road branches off, leading to the fire lookout on the peak above, I noticed out of the corner of my eye that the snow there had been packed down by vehicle tracks. I’d hiked down that road from the peak once and discovered the bottom stretch of it was lined with clearings and informal campsites. If my only other option was to go home and give up on hiking, why couldn’t I at least hike up that road? It was 7-1/2 miles to the lookout, with over 2,000′ of elevation gain. If I made it all the way, that would be a 15 mile round trip hike.

I figured I would drive up the rutted forest road a hundred yards or so, looking for a place where I could park without getting stuck in the snow. Almost immediately I found a big clearing in the mature pine forest above the road. There were no other vehicles, but oddly, there was a tent pitched under the trees, surrounded by a large collection of valuable camping gear, all covered with 8 inches of snow.

I crawled out the back of my vehicle and suited up for a subfreezing hike through the shade of the forest, where I began walking on the hard-packed, now-frozen snow in the tire tracks of vehicles that had been here yesterday. The forest was beautiful under the snow, but the slopes on both sides of the road had been driven over randomly by UTVs and big trucks yesterday, clearly in the afternoon after most of the snow had fallen. I hadn’t realized it, but apparently this was a traditional playground for my town’s off-road enthusiasts.

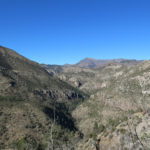

The road climbed back and forth over the gently rolling foothills of the peak, soon leaving the forest and entering the moonscape burn scar of the 2015 wildfire. Above me on the right rose stark snow-white slopes populated with standing snags stripped of bark like toothpicks. Below on my left I could gaze across the entire wilderness landscape, rumpled, snow-blanketed mountains stretching 40 miles to peaks and ridges on the northern horizon. I quickly warmed up and shed ski gloves and heavy fleece jacket. That would be another theme of the day, shedding layers in sunlight and putting them back on again in shade, over and over again. Shortly I came upon a big 4WD pickup truck that had slipped off the road into a ditch, gotten stuck, and been abandoned there.

I could easily spot the fire lookout high over my right shoulder, less than a mile away as the crow flies – but the access road heads east, in the opposite direction, for several miles before climbing to a high ridge and looping back to the lookout peak. And since it runs almost entirely through the burn scar, it’s fully exposed and I’d be getting sunlight reflected off the snow as well as from above. In cold weather I wear a small cap instead of my shade hat, so I had to dig out the sunscreen for the first time since last winter, plastering what little of my skin was uncovered.

After the first couple of miles most of the vehicle tracks ended and I had only two ruts left to walk in, left by two vehicles with completely different tread. The snow was now over a foot deep and I hadn’t even reached 8,000′.

Finally the road left the burn scar and began to climb through intact pine forest. At 8,500′ the snow was knee deep, and the winds yesterday had blown powder into the tire ruts, so it became harder and slower going. Since there was still hard pack under the powder, but I could never tell how deep it was, it was unstable footing and really hard on my hips and knees. But it was doable – without yesterday’s tire ruts I never would’ve been able to hike today.

In the back of my mind was all those vehicle tracks through the forest at the beginning of the road. Would the off-roaders come back today? Every now and then I stopped to listen, but the entire frosted landscape was silent and seemed to be at peace.

After I crossed the ridge, the southern basin-and-range landscape unfolded below on my left, 5,000′ lower, into an endless golden haze. The road follows the high ridge for a couple miles, then dips a few hundred feet to a small saddle, before climbing steeply across a north-facing slope the last mile and a half to the peak. On that last climb I’d be almost completely in shadow and it would be very cold. I toyed with the idea of turning back there – it would still be a decent day’s hike – but as usual I hated to turn back with a clear destination in sight. And I figured I had just enough time to reach the peak and return to the vehicle by sunset.

So I trudged on, climbing hundreds of vertical feet up that difficult snow-covered road, gradually feeling better as I finally neared the peak. My quads were cramping, so I spent my brief time up there doing some long slow stretches.

I was halfway down toward the saddle when I suddenly heard an angry engine growl from somewhere ahead. I scanned the high ridge and finally spotted two dark UTVs driving out of the ridgetop forest and down into the burn scar. Within minutes they reached me. They didn’t slow down, so I had to quickly step off into the knee-deep snow as they raced past – both closed-cab 4-seaters full of high school kids, with the windows rolled up. I waved, but most of them ignored me, one or two waving back as they bounced up the road.

I kept hiking down the road in the shadows, and after a few hundred yards heard more growling ahead of me. This time it was two giant open-cab, open-frame, homemade-looking UTVs designed for travel in deep snow or mud – with at least a couple feet of ground clearance, extra-wide tracks, and tires almost 4 feet in diameter – each driven by a middle-aged guy. They looked like something built for the apocalypse in somebody’s garage. A red-tailed hawk flushed from a snag by the road as they approached and soared out over the void. They slowed and I told them how impressed I was by their machines, and they thanked me before rolling on.

By now I could tell that whatever benefit I’d gotten from yesterday’s tire ruts was being eliminated by today’s UTVs. Because they were lightweight, they didn’t pack the snow down, and because they drove fast and bounced on soft springs, they spread the snow back over yesterday’s ruts and created wavelike softer and harder patterns that were really hard to walk in. If I’d known this I never would’ve started up the road, but now I was stuck, with another 6 miles to go.

Moving more slowly now, I passed the saddle and began trudging up hundreds of vertical feet to the high ridge. There I encountered a smaller open-frame UTV driven by an old guy with a ZZ Top beard. He didn’t look or slow down as he passed me, so I yelled “It’s like a freeway up here!” and he gave me a vague wave.

From then on, I could hear engines in the distance, all the time. With the snow tossed around by so much UTV traffic, the road was getting harder and harder to walk. But finally I reached the end of the ridge and began descending, although the snow was so unstable, going down really wasn’t much easier.

Suddenly I realized my cap was gone. That was a new cap, ordered from San Francisco! I looked all around, but I had no idea when I’d lost it, so I gave up and kept trudging down. Then I realized it was time for a drink of water, and when I unshouldered my back, the cap fell off it onto the road. It had slipped off the back of my head and was just perched on the sloped lid of my pack, with nothing but friction to hold it on.

Shortly after that I was passed by the high school kids’ UTVs, again racing past without slowing, forcing me off the road into deep snow. I was now out of the forest, crossing the burn scar, with the vast northern wilderness laid out to my right and the bald toothpick slopes rising on my left. Rounding a broad turn, I saw an unfamiliar open-topped UTV ahead, parked just off the road. There was a young guy standing on the side of the road scratching in the snow with a branch, and sitting in the UTV watching him was a beautiful young Native girl, with long braided hair parted down the middle like something out of a 19th century painting.

As I approached them I noticed writing in the bank of snow along the road: “Suck Me” followed by something I couldn’t read. “Suck Me!” I yelled, laughing. “So that’s the word of the day!” They both cracked up and I wished them more fun. The whole thing was finally becoming clear. This area really was a traditional playground for the local working class folks, who work hard to afford their expensive mechanical toys, and yesterday’s snow was an opportunity none of them could pass up. Today was their big day to celebrate.

Across the next long bend, I could hear an engine laboring and men yelling. I saw two pickup trucks pointing up a steep, shaded section of the road, one of them obviously stuck in the snow.

More young people. There was a couple sitting in the stuck truck, the guy revving the engine, spinning his tires, as two other guys tried to pull from the back with a nylon strap. The young guy had obviously been trying to impress his girl, driving up this steep road in the deep snow, and it backfired. I didn’t see how they were going to get it out – the other truck was no bigger and no better prepared for towing – but I wished them well.

Around another bend, and I came to another pair of trucks, one of them stuck, too. The young driver was obviously pissed – I asked him if they’d tried laying branches under the tires, but he just spat “I’ll get it out!”

Shortly after that, the two giant UTVs driven by the middle-aged guys overtook me going down, waving as they passed. The road was entering the foothills where it wasn’t so steep, and ahead I saw two big 4WD pickups parked on a rise beside the road, with middle-aged men and women standing around as their kids played in the snow. A younger man dragged two laughing tots on a sled down the road toward me.

“There’s two trucks driven by young guys stuck up there,” I said to one of the older men. “That’s why we stopped here,” he said, laughing. “You really need UTVs for that stuff.”

More UTVs passed me coming up the road. I started down through a small patch of forest with a clearing and corral, and saw two kids sledding and a big SUV parked by the corral. As I was passing them, more UTVs driven by older men raced up the road toward me and I dashed out of their way.

Shortly after that I heard another engine behind me. It was the big SUV from the corral, towing two kids sitting in inner tubes at the end of long lines. They were moving slow so I had to wait a long time, standing off the road in knee-deep snow, for them to pass.

Finally I approached the end of the burn scar and could see the forest below. Another open UTV approached me driven by an older Hispanic man with his wife. At least half the people I’d seen today were Hispanic, matching our local demographic. They stopped to ask me if I was okay and if I needed a ride or some water. Despite the fact that I was warmly dressed and carrying a backpack, everyone I’d met acted as if walking were a sign of something terribly wrong.

As I walked down the road into the gently rolling forest I could hear a lot more noise ahead, and vehicles parked off the road in the deep snow under the trees. A young woman raced up the road in a single-seat UTV with two smaller girls hanging on her back, asking me if I needed help. There was a big family party going on in a clearing under the trees on the right side of the road. There were no tents or RVs, but they’d set up tables and stoves and had a campfire going, and there were kids and dogs running around. The folks nearest me waved and smiled. A little farther down I passed an even bigger party on the left, with a roaring fire and half a dozen big pickup trucks parked randomly in the snow under the trees.

Then I saw another big party farther back in the trees, and another up ahead on my right. I was getting near the end. Suddenly an old pickup truck pulled alongside me, driven by an old long-haired guy wearing a cowboy hat who looked like a Mexican bandit out of an old movie. He couldn’t roll his passenger window down, but he frowned and used sign language to ask me if I was okay. I’d been picking up trash in the road so I couldn’t sign him back, but I yelled I was fine and after a while he drove on.

The young girl on the UTV passed me again and asked if I needed a ride or some water. I couldn’t count the offers for help I’d had so far. Most people were worried about me, and nobody could understand why I was walking.

Finally I reached the big clearing where my vehicle was parked. There was another big party going on there. The tent and all the camping gear had disappeared, and several more pickups surrounded the spot, with stoves set up on tables and campfires burning on the ground. This party was strictly young folks, and I could see tall liquor bottles in the cab of the nearest truck.

I smiled and waved yet again. My whole lower body was sore from 15 miles of walking in unstable snow. The temperature had climbed slightly above freezing at this elevation, and my door locks had melted free. Still, it was a stressful drive back through the mountains, because the traffic was now relentless and the shaded asphalt still bore long patches of ice and frozen snow. Even after sunset, people were streaming from town out into the mountains. At one point where the icy road topped a rise and the ice cleared, there was a Prius stopped in the opposite traffic lane, rightly afraid to go any farther. An out-of-state plate – a tourist learning about our conditions the hard way. They’d be lucky to get turned around and make it back out of the mountains.

December 20, 2021

The Hike That Almost Wasn’t

This Sunday’s hike barely happened. I won’t bore you with the details, but Saturday was hard, I got up Sunday assuming I wouldn’t be hiking, and by the time I decided I might as well give it a try, I was almost two hours late getting to the trailhead.

Starting late, I should’ve done the hike near home, but my mind was still obsessed with that area over on the west side of the wilderness. Without the time for a serious exploration, I decided to hike the canyon-to-ridge trail that I’d previously given up on as too much trouble for too little payoff. If my body held up, I might be able to reach the junction at 9,000′ where another abandoned trail branched off into unknown territory. I didn’t expect to get much farther in the limited time I had, but at least I’d get a sense of the condition of that old trail.

It was another crystal clear day, just below freezing.

One reason I’ve avoided this trail is the condition of the canyon bottom. The canyon is narrow and very rocky, and would be spectacular if it weren’t choked with deadfall and post-wildfire thickets. All the crowd-sourced websites show the trail from the canyon to the ridge top as 3.8 miles, but they omit all the zigzags, switchbacks, and up and down sections required to avoid obstacles in the canyon bottom. And because of the towering cliffs and forest cover, I’m sure there are huge gaps in everyone’s GPS readings. The hike to ridge top takes a minimum of two hours, and I’m convinced it’s closer to 5 miles.

The saddle at 8,240′ is no place to linger. That’s where I hit the first patches of snow from our storm a couple weeks ago, and the north slope below the saddle was coated by a couple inches. The trail continues straight east up the next steep section of ridge then starts a series of six long switchbacks, none of which are shown on the maps, before traversing around a white conglomerate cliff into the bowl at the head of Little Dry Creek. There, you face the arc of ridges that top out at over 10,000′. I’d previously bushwhacked up to 9,800′ there, but now I was hoping to turn off onto the abandoned trail at about 9,100′. I was looking forward to getting above 9,000′ for the first time in months – usually the higher elevations are inaccessible this time of year due to deep snow.

There was virtually nothing left of the old trail, but I clambered over deadfall, followed gaps in the oak seedlings, and used occasional sections of tread maintained by elk, for a few hundred yards, reaching a level clearing on the shoulder of the next outlying ridge.

Beyond that clearing, a solid thicket of Gambel oak had completely obliterated the trail, but another couple hundred yards past the thicket, I could see the old trail crossing a wide talus slope. That’s one of the few good things about talus – as long as it stays clear of vegetation, it preserves trails.

Due north of me were some of the highest peaks in the range, and thousands of feet below me were the parallel canyons of Spruce and upper Big Dry Creeks, whose junction I’d bushwhacked to last July on another abandoned trail. It was a great view, but all that country was essentially inaccessible to humans now due to post-wildfire deadfall, blowdown, and regrowth.

Since I couldn’t get any farther, I had some extra time. I hung out there for a while, soaking up the views, eating a snack, and reminding myself not to rush the return hike. I hadn’t even expected to hike today, so it was sort of a free day anyway.

Unlike the other hikes I’d done recently, this return was almost all downhill. Not to say it was easy – in addition to the usual loose rocks, I faced that canyon obstacle course, which is equally hard going up and coming down. But I finally realized I just had to stop thinking of it as a trail, and treat it as a bushwhack. So much of hiking is in your mind, and your mental attitude.

December 13, 2021

Unstoppable Urge

Midway through the past week, I’d finally succumbed to another episode of severe back pain – a continuous level 7 on the pain scale – which was then added to the chronic foot inflammation and the burning sensation in my hip – which now seems to be connected to the back thing. I was virtually immobilized for a couple days due to a perfect storm of delays in the healthcare system, then spent another couple of days operating at half capacity on meds.

It takes a week or two for episodes like this to subside, so why would I even consider going for a hike only four days after onset? Why does the Pope (blank) in the woods?

After all, walking is generally considered good for back pain, although I haven’t always found that to work.

Early Sunday morning, the edge-of-your-seat Formula 1 season ended with a bang, with two drivers equal on points, and the young challenger passing the much older 7-time world champion on the last lap, the young driver admitting he’d had a terrible leg cramp at the time. How could I wimp out of a hike when faced with an example like that?

The rational thing would’ve been to choose an easy hike close to home. But after four days of severe pain, I was hardly rational. Like a rampaging zombie, I followed a deep-seated urge to return to the area I’d been hiking for the past two weeks, and re-tackle the trail I’d previously sworn was too rocky and dangerous on my feet. But as usual, I did bring the meds, just in case.

After finally getting a little rain a couple days earlier, it was several degrees below freezing at home, under a crystal clear sky.

Remembering how upset I’d been about the terrible footing on this trail the first time I’d hiked it, I vowed to revisit it with a positive attitude and take the dreaded volcanic cobbles in stride, slowing my pace, increasing my concentration, and allowing extra time where needed.

But two miles in, after crossing the seemingly interminable rolling basin and starting up the rocky slope to the pass, I found something else to annoy me. At the trailhead, I’d read a recent log entry by the Back Country Horsemen, who proudly and excitedly proclaimed that they’d “cleared” about ten miles of trail. Of course, this trail had already been cleared recently by another volunteer group, and I’d found it in good shape in September. What I found was that the horsemen had unnecessarily mutilated beautiful and valuable wilderness habitat, cutting back or cutting down hundreds of trees and shrubs as far as 8′ off the trail, while ignoring thorny catclaw and locust seedlings that remained the only impediment to hikers.

On a day hike, this incredibly rocky trail is a lot of work for a small payoff. But the payoff still seems to be enough to keep drawing compulsive hikers like me – and of course the lazy back country horsemen, who let their pets do all the work.

Shortly after crossing over the pass into the backcountry, I came across the first pile of junk left by the horsemen – some kind of heavy, unidentifiable camping apparatus which had just been leaned against a tree beside the trail. I’ve been finding junk left in wilderness far too often lately, but this was so heavy I wasn’t excited about carrying it out. Why would they leave it in the first place?

With my determination to enjoy the hike, the segment to the high pine park seemed to go quicker than before. My back pain was there, but walking did seem to keep it manageable.

Unfortunately, while crossing the beautiful pine park I encountered the second pile of trash left by the horsemen – six 5-gallon collapsible plastic water carriers, all punctured in various ways, probably by a bear. Had they stupidly left them there full of water, thinking to make them available for future visitors? Several times on popular trails I’ve come across water bottles left for hikers, and it always seems like a well-intentioned but naive idea – leaving plastic waste that’s sure to attract wildlife. This was the worst example I’d ever seen.

From the pine park I dropped a few hundred feet to the junction where the horsemen had descended into and crossed the big canyon northwards toward the West Fork. As before, I passed the junction, continuing straight up the ridge above the canyon, through the burn scar of last summer’s fire, to the saddle where the trail begins descending into the heart of the big canyon, deep in the wilderness.

Following my unstoppable urge, I’d decided to try reaching the creek crossing down there – a fifteen-mile round trip with 3,500′ of accumulated elevation gain. Would my wrecked body endure it?

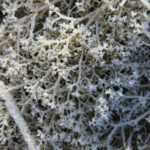

Starting down the trail into the canyon, I entered another world. The tread was narrow and very steep in sections, but I had long, dark volcanic cliffs to admire on the opposite side. The trail passed in and out of forest, scrub, and oak thickets, veering back into deep side canyons where recent post-fire erosion had created logjams and rock berms. It traversed the slope eastward for the better part of a mile, then began dropping hundreds of feet down into the canyon on long switchbacks. This was a north slope so it was holding a lot of moisture, and not just from last week’s rain. I had my sweater back on descending this shady slope, and the moist ground was frozen solid and covered with frost.

I reached the creek sooner than I expected, in a lush, damp, chilly green swale. The canyon was narrow here but I could see the trail continuing east onto a broad flood plain forested with ponderosa up to a hundred feet tall.

After last summer’s fire, the canyon bottom was a strange place. Lush with grass but lined with ashes and char, the floodplain, which was probably a great camping area before, was uneven from post-fire erosion and deposition, and the tall pines had been charred for dozens of feet up their trunks, some of them killed, others with surviving crowns. I was excited about reaching this place, but as usual, I’d pushed my available time and needed to rush back in order not to get lost in the dark.

Although in the past 3 months I’ve been hiking over 50% less than before, I seem to have somehow retained my conditioning, because the 800′ climb out of that canyon back to the ridge felt really easy. I’d put a fresh metatarsal pad on the orthotic for my sensitive foot, so it seemed to be doing better – you really need to keep up maintenance for a condition like this.

With little more than a week ’til the winter solstice, the sun was dropping rapidly, shadows were deepening, and I treasured what little light I could get going back along that exposed ridgeline toward the pine park.

I hadn’t planned on trying to pack those big water carriers out, but when I reached them I just couldn’t stand leaving them without a try. I had a plastic bag that, with a lot of forceful crushing, accommodated three of them and barely fit inside my pack. I crushed the other three and used my nylon strap to secure them on the outside of the pack. They hardly weighed anything.

After another mile and a half traversing toward the pass, I reached the weird heavy camping item. Yep, it was heavy – 12 to 15 pounds. But it had a handle, and I remembered the young Formula 1 driver who won the race with a leg cramp. So I began carrying it out.

The next three miles were just an ordeal, but I stuck to my determination to keep a positive attitude. There were places where stumbling or twisting on the incredibly rocky trail triggered my back and hip pain, and I ended up taking a pill, and then another an hour later, realizing it was ridiculous to suffer when I had the means to relieve it.

As on the previous Sunday’s hike, it was almost completely dark when I reached the trailhead, but my eyes had adjusted well and I only used my headlamp to unload and rearrange stuff in the vehicle. I left the weird rolled-up camping device at the trailhead – it seemed to have some sort of faded, vaguely official printing on it.

And since this trailhead is really remote, on roads I’m still unfamiliar with, it was a long slow drive home, but I was feeling pretty good about what I’d accomplished.

December 6, 2021

Stone for Joan

Last week’s hike was so epic, it would be hard to top – and besides, I needed to take it easier on my recovering foot and hip. By Sunday morning, I’d convinced myself to head east of town to repeat an easy ridge hike I’d probably done a dozen times before.

But as I packed for the hike, I found myself longing to return to the same area I’d hiked last week. It seemed I just couldn’t get enough of that place – it was the rockiest area I’ve found in our local mountains. Including last Sunday’s hike, I’d hiked the ridges on both sides of the ten-mile-long canyon, but I hadn’t explored the abandoned trail in the canyon bottom, which would be passing between and looking up at all those stone promontories, cliffs, and pinnacles.

The only recent information available on that trail comes from the website of a guy who’s obsessed with waterfalls. He and a friend went up the canyon in 2018, encountering a 75-year-old man who they claim “has long been repairing and maintaining trails that the feds have discontinued and abandoned”. Frankly I was skeptical of their story, but I’d printed out their low-resolution map and would give it a try. If the trail turned out to be a bust, I planned to follow the main trail to the next ridge and bushwhack off it up the ridge as far as possible, to look down on the canyon from a different perspective.

But if I succeeded in following the abandoned trail through this wonderland of rocks, I would dedicate this hike to my mother, Joan, who is always asking me for “more rocks”!

It was a clear and cold December morning at home – 37 degrees. At the trailhead I found only one log entry since my visit a week ago: someone from the nearest village who said they were going fishing in the creek. I was a little bemused since in my experience the creek had been ephemeral and intermittent and I’d never seen fish in it.

But down the trail a bit, when I got my first view into the big bend far below, I saw a bright ribbon of water, and as I hiked lower in the morning sun, shedding my jacket, I could hear the creek rushing noisily over rocks in the canyon bottom.

The mesa around the trailhead is heavily used by cattle from the Moon Ranch, and fresh cowshit preceded me down the rocky trail, but disappeared by the time I reached the wilderness sign a half mile in. I saw no sign of cattle in the canyon itself.

The canyon bottom was dark and so chilly I had to put my jacket back on. It’s a mile and a quarter down into the canyon and across the creek to the junction where my favorite trail continued up the other side, and where I believed the abandoned canyon trail branched off north. The canyon trail is not signed – there’s only a fallen, broken sign for the ridge trail.

I headed up the unmarked branch, and found it to have good, but very narrow, tread. The map showed it closely following the creek, but that’s at low resolution. In reality it climbs high above the creek to clear obstacles, then drops down and crosses to the other side to avoid more obstacles, as the creek itself winds back and forth through this 2,000′ deep canyon.

For the first quarter mile or so I found it easy to follow. I didn’t see any evidence of trail maintenance by the mythical 75-year-old. It was blocked occasionally by deadfall, but less so than many of the regularly maintained trails I use. There were cairns, but most of them were minimal, buried under vegetation, and hard to see. From the abundant recent scat, it was clear that bears were the most active users of this trail. They, not some phantom human, were keeping it open for the rest of us.

I was eagerly hoping to get to the really rocky part of the canyon, but my progress was slow because the trail was so hard to relocate at its frequent creek crossings. The creek itself disappeared underground before I’d gone too far up it, leaving a broad dry bed of cobbles. But I gradually came to trust the ancient cairns. If you started by assuming they were buried under vegetation, they became easier to find. The trail’s tread might completely disappear for up to a hundred yards, but if you followed natural openings in the vegetation and rock formations, you’d eventually be able to find another buried cairn.

I was anxiously watching for a big side canyon to open up on the left – the big canyon I sat above in the stone saddle at the end of last Sunday’s hike. I’d been curious as to whether you could actually hike that side canyon. When I finally reached it, it appeared at the bottom as a broad washout, old enough to have cairns and descending tread on both banks. But once across that washout, it took me forever to locate the next cairn and the continuation of the trail. From there on, I expected to see more rock – I’d be passing directly below the monumental rock formations I’d looked down on last week.

The canyon did get a little rockier, but the upper slopes still lacked the impressive formations I expected. Back and forth I crossed, looking for buried cairns, following tread when it was available. Suddenly I came upon the remains of a recent campfire – a fire ring filled with ashes and unburned trash – directly in the trail, in a narrow passage where you couldn’t avoid it. What the hell? Who would build a campfire on a public trail, and even worse, walk away without dispersing it? The ashes were really fresh, so I suspect it was the local who came “fishing” only three days earlier.

I kept going, figuring I’d disperse and restore it on my return. And eventually I began seeing some fanciful rock formations on the slopes above.

Now I was in rock heaven, in the heart of the canyon. Bedrock in the canyon floor kept the creek running on the surface, often for long level stretches with deep pools. And cliffs and house-sized boulders forced the trail to climb steeply for up to a hundred feet above the bottom before descending and crossing again.

This local rock is not “real” rock like the sandstones of Utah or the granite of my beloved Mojave – as crumbly volcanic conglomerate, held together by tuff, which is just compacted mineral dust, it’s a poorer quality rock for climbing. But surprisingly, its eroded shapes are similar, from a distance, to the familiar forms of sandstone and granite.

I reached a broad grassy meadow where a tributary creek poured out of a really big side canyon on my left, and up that canyon I could see the back side of the ridge I’d wanted to climb last Sunday, 3,000′ above me now.

My time was getting short. It had been a slow hike, partly because the trail had often been hard to follow, but also because I’d stopped a lot for photos. I didn’t really know how long it would take to get back. But I wanted to reach the point, near the top of the main stem of this creek, where the map showed the trail finally leaving the canyon proper and clinbing up the right-hand slope to the ridge above the canyon, marked “steep difficult trail” on the map. That would be a real milestone.

Unfortunately, past the big side canyon, which was already quite a ways past where I’d hiked last week, I entered a long stretch of narrow canyon shaded by towering walls, where the trail had to climb even steeper and higher above the creek to avoid giant boulders and cliffs. I was racing against time now.

Again and again I dropped down a steep left-hand slope and crossed to the right side of the creek, thinking this might be the place, only to find the trail recrossing to the left side again. Finally I reached a point where the left-hand wall of the canyon seemed to come to an end. The trail crossed the creek and climbed a short ways to where it was blocked by deadfall, with no visible tread beyond. I unshouldered my pack, sat on the big log blocking the trail, pulled out my map, and saw that I’d in fact reached my goal – this was the base of the trail to the ridge top! A short distance up the canyon was the top of the main stem of the creek, where three major tributaries came in from west, north, and east.

What a canyon! This was definitely the rockiest, most spectacular place I’d found in these mountains. And once you knew what to expect, it was surprisingly easy to hike.

It was getting late. I wasn’t even sure how many miles I had to hike back, let alone whether the return hike would be easier now I’d done it once. My only hope was that I’d reach the main trail in time to use my headlamp, because there was no way I could find all those buried cairns after dark.

The return did prove to be easier. I stopped and dispersed the campfire on the trail, and restored it as best I could. We’re expecting rain this week, so that should help finish the job.

On the long hike down the canyon, I realized I preferred this to all the other actively maintained and “recently cleared” trails I normally use. This trail has just enough tread and markers for me to be able to follow it, without being easy for other hikers. I didn’t see a single human footprint on the trail, and hopefully mine will quickly wash away. The old hiking trail is basically just a really good game trail at this point. I’d like to keep it a secret for me and the bears.

In the end, the sun set nearly a half hour before I reached the main trail, but my eyes adjusted to the gradually falling darkness so that I didn’t even have to use my headlamp climbing out of the canyon.

On the 20-mile drive down the mesa, I stopped when I realized the night was as dark as it was going to get.

I got out of the vehicle and gazed for a while at the Milky Way arching overhead, picking out the old familiar constellations. Despite living under one of the clearest skies on our continent, since my house fire, I hadn’t had a chance to relish a night sky like this. It felt so good.

November 29, 2021

Haystack Bushwhack

Lord, how I needed this hike! After the last venture into our local mountains, I’d flown to the flatlands of Indiana where I was able to do one 14-mile out-and-back in modest hills before succumbing to, in succession, severe hip pain and a recurrence of my chronic foot problem. I’d had to suspend strength training a month earlier while moving back into my fire-damaged house, and I was hoping that explained the hip trouble – maintaining my mobility requires a lot of bodywork “behind the scenes” and between hikes.

So now I was icing the foot and lifting weights and doing core exercises again, and I was determined that this return to hiking would be fairly easy, without extreme distance or elevation gain.

However, when reviewing my options, I found myself drawn to a new idea – starting at the trailhead for my favorite hike, and bushwhacking up what looked like a gentle ridge through open pinyon-juniper-oak woodland toward Haystack Mountain, a distinctive but only moderately high peak. The ridge continued all the way to one of the highest peaks of the range, so this would be a scouting trip to see if it was a feasible route to the top.

The temperature at home was in the mid-30s, but it was forecast to reach 60 by midday.

I only found out how badly I needed this trip when I crested a divide on the highway and got my first view of these mountains, and involuntarily broke out in a big smile, feeling my heart lift.

From the trailhead at the back of the mesa, the foot of the ridge appeared as a low, broad, gentle rise. I followed a vague cattle track up the slope of dried grass to the tree line, where I found a well-traveled but very rocky trail that traversed left across the rise. Very tough to walk, but it led me through fairly dense and steep forest to a barbed wire fence with a closed gate, and along the way I noticed fragments of a strange footprint featuring what appeared to be football cleats. The print was roughly round and didn’t have the outline of a shoe, and I kept watching for it all the way up the ridge. It was the only track I found that wasn’t from a recognizable animal.

Past the gate I crossed a broad, gently rising meadow that turned out to be lined with sharp embedded volcanic rock which was very difficult and slow to negotiate safely. It was probably still in the low 50s, but I took off my sweater while laboring across that sunny ledge. Then the slope steepened through more low forest, and I began finding more cattle trails that allowed me to walk faster. The cattle trails got better and better and I found more of the strange cleat marks, still without a clear footprint. Like cattle trails I’d found recently in the Blue Range, long stretches looked man-made but clearly couldn’t have been. This was inside the wilderness area, but there were cowpies of all ages, from decades old to within the past week. I was also finding a bobcat track, deer tracks, and lots of javalina prints.

The narrow ridge rose in steps, revealing deeper and deeper views into the wilderness on both sides, until I lost the cattle trail and the ridge ended suddenly in a drop-off. I checked my map and saw that I was at a major dogleg – I had to turn right and find my way through dense forest and scrub to the next left turn, where the ridge descended toward the foot of the peak.

At the left turn, I found another cattle trail leading down, but it ended in a grassy saddle, and from there on it was hard bushwhacking.

Finally I reached the last grassy rise before the base of the peak, where I could start scouting my route. There, I found elk scat that was so warm and moist the animal had to have been there earlier today.

From the south, the peak had looked sharply triangular, but from here it was rounded. My ridge led down to a saddle densely forested with ponderosa pine, the first I’d encountered today, and then directly up an outlying toe of the peak. The map showed that the upper few hundred feet of the peak were quite steep, but the lower slopes looked gentle. Vegetation was patchy – dense forest at the bottom, grass and rocks in some places, and dense scrub in others. It looked like I could climb the first rise to get past the deep ravines surrounding the base, and from there, traverse through scrub to the next outlying shoulder, where I could see a line of tall ponderosa.

My goal was not to climb the peak, but to traverse around it, ending up at the level of the next saddle. My plan was to see how far I could get – I still had enough time to explore the next part of the ridge, where it climbed over 800′ higher, to the 9,000′ level, which would be really rewarding.

Unfortunately, past the tall pines of the saddle the forest of the lower slope turned out to be steep and so dense as to be near impassable. I kept pushing and zigzagging and finally broke out into the grassy upper part, but it was equally steep and very rocky. It seemed to take forever to reach the point where this shoulder merged with the upper slope, and there I found my traverse to the next shoulder blocked by dense chaparral.

Nevertheless, I forced my way through it, taking advantage of game tracks whereever possible. Way up there like a fly on the wall of the vast western landscape, I was clinging to a 40 degree slope with a lot of loose dirt, so it was dangerous going and hard on my vulnerable foot.

But worse was coming. When I reached the next sharp outlying shoulder and made a sharp right turn to the back side of the peak, I found a seemingly endless, deeply shadowed talus slope at the same 40 degree angle, that had been densely colonized by oaks of various ages and blocked often by pine deadfall. To cross it involved contorting my body and achieving a delicate four-point balance with every limb at nearly every step. The traverse was only a few hundred yards but it took about an hour.

Fortunately, the view I got at the end, back on the main ridge, was almost worth it.

After emerging from the oak-infested talus slope, I found myself a couple hundred feet higher than I’d intended – and what a view was opened up! Northeast over the upper canyon of my favorite trail – a canyon that had impressed me from the opposite direction, for its rocky majesty. But from here it was even rockier – the descending slope into the canyon was just a series of white promontories, cliffs and hoodoos. In the moment, this felt like the most spectacular hike I’d ever done in my home region. In the far center of the view was the 10,771′ peak with the fire lookout, and arrayed to its south were the ridges and peaks I’d either hiked to or admired from months of previous hikes.

Below me on the continuing ridgeline was a series of rounded white conglomerate outcrops. I’d had to put off lunch and could already see where I wanted to eat it – in a saddle of solid stone between two taller formations, with a full view into the rocky canyon.

I don’t usually stop for lunch – I just snack regularly while walking, so I can cover more distance. But after that traverse from hell, my body deserved a break. The next slope, the steep way to the next peak, was clear from here, but I’d used up my time for the day.

Although I wouldn’t go any farther up this ridge, I might as well at least climb the peak I’d traversed – it was only about 400′ above this rocky saddle, and the lower slope looked fairly gentle. But starting up it, I was reminded that it lay within the burn scar so it was crisscrossed with dozens of charred logs in every direction. Shortly after starting up I found my way blocked by an odd white tree branch that I suddenly realized was a huge elk half-rack. I stood there staring at it in amazement for a while, then wondered if I should take it with me. I bent to lift it – it would add at least ten pounds to my pack, but at this point I was carrying about 6 pounds less water than I carried at the start of a summer hike. And I suddenly remembered thirty years ago when I found an entire massive bighorn ram skull in the desert, with horns about as big as they get, returning from a backpacking trip, and carried it down the mountain tied to an even smaller pack than I was carrying today. That sheep skull and horns had been destroyed in my house fire, so taking this antler rack was fair in a way.

I carry an adustable nylon strap for situations like this, but this thing was four feet long and stuck out in every direction. It took me a couple tries to find a way to hang it on the back of my pack so it didn’t hit me in the head, and I’d have to be careful not to get it hung up on passing branches. I tried not to think about what would happen when I had to force my way through scrub, or how I might be injured if I fell backwards on that thing. Carrying it home seemed like a fairly stupid idea, but these hiking Dispatches are nothing if not a record of my bullheadedness.

With elk antlers strapped to my back, the climb to the peak was short but slow and grueling. I literally used oak seedlings to pull myself up at every step of the 40+ degree slope. The view at the top was 360 degrees, but really no more spectacular than the view from the saddle below. Still, I was glad I’d done it.

There was no way I was crossing that talus slope again on the way back – I was planning to work my way down the sharp shoulder with the line of ponderosas, and then traverse back through the dense scrub to the lower, more open shoulder.

But less than a hundred feet down that steep shoulder, I noticed that the slope to my left, leading directly to the lower shoulder, was no steeper, and there seemed to be paths through the scrub. So I began working my way straight down the side of the peak, and immediately found game tracks that I could follow back and forth between the dense scrub. It was still really steep, and the only open paths were in loose rocks and dirt – very dangerous with that antler rack on my back to throw off my balance – but I somehow avoided falling and eventually made it to the top of the lower shoulder. From there I could see the rest of my path down the main ridge laid out below me.

On the way up, I’d thought of nothing but how much easier it had been than previous off-trail hikes – because I’d been able to use cattle trails. But on the way back, I realized the cattle trails followed only part of the ridge. Much of my route involved forcing my way through dense, nearly impassable low forest or scrub with sharp rocks underfoot, and before I even made it halfway back I was swearing never to do this again. The sun was steadily setting and I was worried about getting lost if I couldn’t reach the vehicle before dark. My headlamp wouldn’t help because I was in an unfamiliar, mostly forested landscape with no trail.

Finally I reached the edge of the slope above the broad, grassy, and rocky meadow I’d crossed when passing through the gate in the barbed wire fence, 7 hours earlier. And it hit me that I had no idea where in that half-mile expanse the gate was. On my ascent, I’d failed to look back and memorize it, like I usually do when the way isn’t clear.

The lower edge of that sloping meadow was a solid, continous low forest, and the meadow itself was dotted randomly with old junipers. How the hell was I supposed to find the gate? I could see the lower part of the dirt road way off in the distance, but the part of it that led to the trailhead and my vehicle was out of sight below the ridge. I had no way to orient myself. The only thing I could do was head down the middle and hope that something would occur to me on the way.

Nothing did. It was perilous walking over those sharp stones, most of them hidden among the grass and annuals, and the sun kept getting lower ahead of me in the west, causing a glare. Finally I got to the edge where forest resumed and the final slope to the mesa began. A short way down that steep slope I saw the fence. There was no way I could climb over it – the barbed wire was loosely tied to steel posts at long intervals and I’d get hung up and cut up trying to cross. I had to find the gate.

I turned right and began laboriously following the fence through rocks and scrub along the top of the slope. I wasn’t sure I was going in the right direction, but eventually I’d hit the end of the grassy bench and would have to turn back.

Suddenly I came to a gate. This gate was open, so it couldn’t be the right one. But I could at least get through the fence and backtrack. I tried to reclose the gate, but the posts had resettled and it wouldn’t fit. No wonder cattle had been getting through.

Traversing the slope back, to where I could descend to my vehicle, was another form of hell. I discovered that this lowest slope was deeply dissected by gullies that were often too steep to cross, so I had to climb higher to go around them. It seemed to take forever, the antler rack wobbling on my back, narrowly avoiding falling as I stumbled on rocks or slid in loose dirt. In gaps through the trees I saw black cattle grazing around my vehicle, still far below.

When I reached my vehicle, the sun was literally just setting. Close to 9 miles out and back, with nearly 3,000′ of accumulated elevation gain, this was the most extreme bushwhack I’d ever done – a far cry from the easy hike I’d promised myself…

November 1, 2021

Modest Marathon

Like so many other recent nights, the night before today’s hike was largely sleepless, so as the sun finally came up I knew I wasn’t likely to drive a long distance and do a marathon hike. As it was, I got such a late start that the only option was the trail near town that connected with the Continental Divide Trail and was in such good shape that I could get some decent distance and elevation in a shorter time than usual.

What surprised me, when I started up the “primitive” road that constitutes the first two miles of the hike, was the amount of water coming down that canyon, a month after our last rainfall. But that’s the way this canyon is – relatively long so it drains a large area, deep so it drains from 9,000′ to less than 7,000′, rock-walled so there are lots of fracture zones to store water and release it slowly, and with an impermeable bedrock floor so the creek runs mostly on the surface.

I climbed steadily at my fairly aggressive “good trail” rate, up the canyon to the CDT junction in a ponderosa-forest saddle, traversing and switchbacking through mixed-conifer forest up the south slope of the 9,000′ peak, crossing the peak into the burn scar of the 2014 Signal Fire, descending to the lower ridge and traversing its south slope to the farthest point I’d reached earlier this year.

That was 8 miles one-way, so if I’d just turned around and headed back I’d get a respectable hike. But since I’d been able to walk fast, it was still early, and since the trailhead was so close to town, I could spend more time on the trail before it got dark. So I kept going.

Past the outlying shoulder where I’d stopped before, the trail made a sharp left turn and began a gentle descent around the head of a large drainage I’d never seen before, and I soon got a view east, toward the next mountain range, that was also new. Immediate payoff for small effort! The trail had now left the burn scar and was leading through intact forest. I checked my map and saw that somewhere up ahead, the trail crossed to the north side of the ridge, so if I could make it that far, I’d get even more new views.

The timing turned out to be just right. Just before my planned turn-around time, the trail crossed the ridge and began descending steeply on the previously unseen north slope. It wasn’t spectacular, nor was it a true wilderness experience – I could see a dirt road a few hundred feet below – but this had turned into a marathon accomplishment without a marathon effort. By the time I got back I would cover almost 20 miles and over 4,000′ of elevation gain in less than 8 hours.

Just before the descent of the north slope I crossed a large flat area on the ridgetop – what in Arizona they call a “park”. I’ve encountered so many of these anomalous landscape features that I began to ponder their formation.

They’re all almost completely surrounded by a gentle ring of higher ground, usually of varying height, and although they all support some conifers around the edges, they all have a grassy meadow near the center. This one was classic because its surrounding wall was uniformly low. I began to imagine how, over a very long time, the upper slopes of a shallow natural bowl would erode and fill the bottom with sediment washing off the slopes, maybe creating a temporary dam downstream, gradually filling the center so that it flattened out. The center would flood occasionally, preventing growth of conifer trees, which need well-drained soil, and supporting the establishment of grasses. In the end, you’d get this flat expanse high up on a ridge, completely natural but looking just like a man-made park.

On the walk back to the peak, I had the sun lowering ahead of me, backlighting the fall foliage, which in this case consisted not of tree leaves but of the seed heads and dried leaves of annuals. It was a more subtle, golden beauty that you’d ignore in the company of more colorful aspens, maples, cottonwoods, or oaks.

Crossing the peak I was surprised by the glittering of sunlight off the windows and roofs of my hometown, straight ahead and 3,000′ below in the southwest. Guess I should consider myself lucky I have such places so near home.

Although I’d seen recent mountain bike tracks on the trail, I didn’t see another human all day, which is pretty amazing considering this is one of our most popular trails, only 20 minutes from town, it was beautiful, mild fall weather, and it was a weekend. What was everybody doing?

Oh, yeah, it was Halloween, our society’s favorite secular holiday – they were all preparing their costumes!

October 25, 2021

Land of the Lost

In my last Dispatch I said life was only going to get harder, and that was an understatement. But 14 months after the fire, I was finally back in my (still under construction) house, and this Sunday, I was determined to resume hiking.

With only one other hike during the past 5 weeks, and my sanity on a cliff’s edge, I didn’t want to pick something brutal. But I didn’t mind driving, so I decided to return to the area a little over an hour and a half away where I’d only done one short exploratory hike last summer. The accessible hikes there didn’t look challenging at all on the map – the one I was targeting today looked like a ten mile round trip with less than 2,000′ of elevation gain – a walk in the park. With the extra driving, I’d hit the trail late, and I figured on doing only a seven hour hike so I could get home before dark.

It’s an extremely “wild” area – an incredibly rugged range of lower mountains on the New Mexico-Arizona border with a small river draining through it. Like our other local mountains, it’s not a distinct range – it’s simply a lower-elevation section of the continuous mountains that run for hundreds of miles across the Southwest. The topography is so convoluted I can’t even make sense of it with a topo map.

From the New Mexico side, a graded gravel road leads into the heart of the area, lined with dirt pull-outs which all seem to be occupied by long-term RV dwellers, folks hiding out from the modern world.

It’s one of the twistiest roads I’ve ever seen, but fortunately my trailhead is only a ten minute drive from the already remote and lonesome highway.

The trail starts in parklike ponderosa forest, following the bank of a now-dry creek which obviously saw some big floods during our monsoon. I saw one boot track during the first hundred yards, but after that I saw no more sign of humans. The trail was being used only by cattle.

A quarter mile in, the creek was running and I ran into four skittish cows, one of which was a longhorn steer. They’d been fouling the creek pretty bad.

Eventually the trail crossed the creek, marked by cairns, and began climbing. It led out of the riparian forest into open pinyon-juniper-oak, where I stopped for a drink and a snack.

Under the tall pines, I’d had my sunglasses hooked on the front of my sweater, which I needed to take off, so I temporarily hung the sunglasses through a loop on the back of my pack. Then I flipped the lid of the pack open (covering the stashed sunglasses), took off my sweater, and stuffed it into the pack. Then I remembered I’d been carrying the sunglasses, and pulled out the sweater to check for them. Not there, so I began scanning the ground around my pack. Damn! This was the second time I’d lost those expensive sunglasses!

I picked up the pack and looked all around it, still not seeing them. So I left the pack and started back down the trail, watching closely on each side. I made it all the way back to the creek and never found them, so I gave up and began climbing again. Damn! All the stress had turned me into a basket case and I was making bad mistakes.

Halfway back to the pack I suddenly remembered where I’d put the sunglasses, and felt like an even bigger idiot. PTSD is no joke, and I’d unknowingly inaugurated the theme of the day: continually getting sidetracked.

Despite feeling like an idiot, I was really excited to be hiking again, especially in this brisk fall weather. It’d been freezing at home when I left town, but the sky was mostly clear with a forecast of 60s in the afternoon.

I was climbing a southern arm of a branching ridge that would eventually lead to my destination, and the first payoff came as I crossed over a small rise and found myself on the brink of a cliff, the head of a small box canyon lined with stratified white conglomerate.

From there, the trail climbed steeply up a south-facing slope toward the main ridge. Twice it dipped through small drainages lined with ponderosa forest, but mostly it was exposed, and the higher it climbed, the rockier it got. I spooked a couple of mule deer and ran into a larger group of cattle coming down the trail. And as I climbed through the sunlight flies began to swarm my face, which surprised me considering the temperature couldn’t be higher than 60 at that point. Out with the old head net.

But that was a minor inconvenience compared to the trail surface. The final climb to the main ridge was lined with my nemesis, the ankle-wrenching “volcanic cobbles”. This is a surface you can’t avoid – as bad as it is on the trail, it’s even worse off the trail. This had been the surface on my first hike in this area, but for some reason – probably PTSD again – I’d come here in denial, expecting this trail to be different.

At the top, the trail entered more parklike ponderosa forest and began descending the shallow slope of a seemingly endless forested bowl. This area had been heavily grazed, and in the flat bottom of the bowl the trail led through an open gate into a primitive corral. A black calf stood staring at me to the left of the corral, and its mother stood staring on the right.

On the far side of the corral stood a big cairn. From the map I’d expected to find the junction of this trail with the main trail that came up from a campground 3 miles away, but there was only one trail leading on from the corral, and it seemed to be going the wrong direction, southwesterly toward the campground instead of northward up the ridge. Not having any other option, I started down the well-trampled trail, which followed a barbed-wire fence. It didn’t look promising, but maybe it would get better.

Like the previous section of trail, this one also had been used only by cattle. And suddenly it ended in an overgrazed clearing. I scouted around the edge of the clearing, and eventually found a little tread leading into the forest on the far side. I followed this, and it led down into a ravine. I kept going a few hundred yards, and then the tread ended under a juniper. I didn’t think my trail was supposed to go downward at this point, but for some reason I failed to check the map.

I headed back toward the corral, and a hundred yards from it I saw another trail branching off, with a cairn. I was now completely confused, but I followed the branch, and soon came to an old signpost, on the bank of a deep gully across from the corral. Now I understood. The trail I’d been following was indeed the trail from the campground, and this was the junction. But it still wasn’t clear where to go from here. A small gully led down from the north, and a much-trampled trail continued northeast through the forest. I couldn’t see any evidence that the gully had ever been a trail, so I started up the trampled trail.

This led into the small valley of a dry creek, and after a quarter of a mile it petered out. It was nothing but another cattle trail.

I finally decided to check my map. Fortunately I was never confused about directions – I had a watch, and my shadow showed which way was north. The map clearly showed that the hiking trail led due north from the junction at the corral, climbing straight up the next slope of the ridge.

On my way back to the junction, I glimpsed a gap sawn through a fallen log, a hundred feet away in the forest to the north. Finally, sign of a trail! I returned to the junction and sighted up the little gully toward the log gap. Apparently the gully had been the trail at one point, so I started up it.

I was actually trying this trail because the Forest Service website had a map showing “cleared trails” in this area, and as I recalled, this trail was listed as having been cleared only two years ago. But that clearly wasn’t true. I’d hiked trails near home that had been abandoned for almost a decade and were in much better shape than this.

I was beginning to confirm a suspicion about this area. There’s almost no information on the hiking trails here – they’re simply omitted from most topo maps, and none of them is featured on the crowd-sourced hiking websites. The Forest Service map I looked at shows an extensive network of trails, but there are no descriptions available anywhere, and no record of anyone ever hiking here. From a hiker’s point of view, this area is Terra Incognita – which has a certain attraction to me.

The trail had been easy to follow to the corral, but from here on it barely existed. If I hadn’t already spent the past year bushwhacking and routefinding, I simply wouldn’t have been able to get any farther without GPS. And I suspect that even GPS wouldn’t show these trails.

There was no tread past the log gap, but I saw a blaze on a ponderosa up ahead. Past that I simply climbed straight up the gentle slope, where the ponderosa forest ended and pinyon-juniper-oak resumed. From the trail I’d hiked last summer I knew the way would sometimes be hinted at by a “corridor” through the open forest, but an open forest is full of natural corridors, so it can be impossible to figure out which are man-made.

Across clearings, I followed what seemed to be hints of bare ground, but there was precious little bare ground among the hard-to-walk-on volcanic cobbles. Suddenly I came upon an old dry-rotted tree branch laid between two rocks perpendicular to my path. This is the kind of thing trail-builders use to control erosion, but here it was set up on level ground. I could only interpret it as some unfamiliar kind of trail marker.

In addition to the perpendicular tree branches, I sometimes found small, almost random-looking cairns, which encouraged me to keep going. I was getting higher on the ridge, so I sometimes had views of the surrounding landscape. It remained confusing, but I did recognize the peak I’d seen from the other trail, with a fire lookout on top.

I often found myself without any clear path forward, and had to stop and scout around for clues, so it was slow going. I had little hope of reaching my destination now, and was starting to despair. This whole place was overgrazed and littered with cowshit, and clearly wasn’t maintained for hikers. And my pants were collecting the nasty burrs of cosmos, which carpeted the ground nearly waist-high.

Midway up the ridge, I was following a little stretch of tread when I reached a dead end below a densely forest bank. I turned left and spotted a big cairn in a clearing up a short slope, so I headed up that way, although there was no trail visible. Then I had to spend some time scouting which way to continue.

The perpendicular branches seemed the most consistent trail markers, but they were often so primitive they were easy to miss, and there was seldom any other sign of a trail nearby.

Nevertheless, I eventually found myself heading toward a distinctive, conical, rock-topped peak. I assumed this was my destination – I recalled there was another trail junction on the lower slope of this peak, with branches leading east and west. So now I was motivated to keep going.

Several false starts later, I reached the base of the peak, and immediately, instead of a junction, found a clear trail that appeared to traverse through ponderosa and fir forest around the peak to the northeast. This was not at all what I’d expected, but it was such a clear trail I followed it anyway. I was now close to 8,000′, which was about the highest I would get in this area.

The trail still didn’t show any recent use, but it was such a relief to be on an easy trail that I kept going until it curved around to the north, clearly skirting the side of the peak. Finally I got my map out again, and found that my destination was still farther ahead. On the north side of the rocky peak, there lay a long series of saddles that formed a bridge to the base of a higher ridge, where hopefully I would find my junction.

I was now officially out of time. It had taken me so long to find my way here, if I turned back now, I still wouldn’t get home before dark. But I was so tantalizingly close, there was no way I could turn back yet. I just had to reach that junction. On the other hand, I was beginning to suspect my original estimate of distance and elevation for this hike was way off.

Now knowing how to interpret the signs, I was doing pretty well until I reached the base of the high ridge. There I was stumped by a small clearing with no apparent way forward. I found the remains of an ancient campfire, and after 15 minutes of scouting finally decided to climb over some deadfall and continue up through dense forest. Another corridor opened up, and another, and suddenly I came upon the junction signpost. It showed my overall one-way distance as 7 miles – two miles farther than expected – and made even farther by all the sidetracks and false leads.

It now appeared I couldn’t get back home before 8:30 – but I didn’t care. I felt great, and I was so pleased to get here that I didn’t even really want to head back.

Despite being at the base of a ridge, less than 8,000′ in elevation, the junction was sort of on the rim of the whole area, but although I was able to get occasional long views, trees generally got in the way.

I expected the return hike to be easier now I knew the way, but it was just as hard to routefind in reverse. I got lost several times, pursuing sidetracks down open hillsides and tight gullies, adding hundreds of yards and dozens of vertical feet to my hike. I stopped a lot to take pictures, but walked fast in between, despite the perilous footing on the rocks, and it took exactly two hours to reach the corral.

There I could see what had happened to the old trail – it had been cut by a ten-foot-deep erosional gully right next to the corral.

Next to the corral were two cows and two calves, all black. When they saw me, they stupidly ran into the corral, where they panicked and proceeded to run in frantic circles, until one cow and her calf jumped over the fence. The other cow seemed to believe her calf couldn’t make it over, so the two of them kept circling, as I stood still next to the open gate. The cow finally got up the courage to rush out the gate, and the calf followed.

I continued up out of the bowl, and at the top, again lost the trail and made a false turn. I was headed down the wrong ridge in the setting sunlight when I suddenly realized I was lost, turned back, and easily found the right trail. It could’ve been a bad scene after sundown, miles from my vehicle in unfamiliar forest…

But it got worse. When I finally reached the creek bottom, the trail ended at the bank and everything looked unfamiliar. I knew this had to be the right creek, but there was simply no trail, and no marked creek crossing. I scouted around for several minutes, and finally crossed the creek and climbed the opposite bank, where I found myself in another primitive corral, which I’d never seen before. It was getting dark and now I was really worried. Where the hell was I?

I crossed the corral and kept going down the left bank of the creek, but there was simply no trail here. I could see a narrow cattle trail on the opposite bank, so I dropped into the creek and climbed up the steep bank. I continued down the creek on the cattle trail, completely confused, and suddenly came upon the original trail, cutting down the slope from above. Ahead, I could see a cairn marking the creek crossing I’d taken this morning. Like so many times today, cattle trails had led me off my hiking trail, but I’d finally found it again.

On the long drive back in the dark, I devoted myself to putting together a recipe for the easy but delicious dinner I was going to cook when I got home. And the next day, when I calculated the actual mileage and elevation for my hike, I found that including all the sidetracks and mistakes, the distance and elevation gain had been 50% more than expected. So despite the frustration and stress, I was pleased with that as well.

October 5, 2021

Turning of the Season

Two weeks without hiking! Life was only going to get harder in the weeks to come. I just had to get away for a day – maybe to that “range of canyons” on the Arizona border.

Like so many times before, I swore I would do an easy hike – from the first, most popular trailhead, a 9-mile out-and-back peak climb with 3,100′ elevation gain. Only a half-day hike, leaving me time for another short hike if I felt like it, an early burrito and beer, and a reasonable drive home before dark.

Since my last hike, our weather had flipped from monsoon heat to fall chill. Everyone agreed that this monsoon had been our best in over a decade. But most people had only experienced it in town, in the form of flooded streets, rain and hail on windows, pets frightened by thunder. I’d experienced it deep in the wilderness, soaking wet from sweat, dew, or cloudbursts, struggling through rampant vegetation, with lightning striking nearby. In this new cooler, drier regime, I found myself looking forward to winter.

At a thousand feet lower than home, the weather at my destination was forecast to be mild and partly cloudy, with no chance of rain.

I got an early start, but by the time I reached the trailhead, the parking area was filled with half a dozen vehicles. I checked the time. There was another hike I’d really been hoping to do here, but had decided would just take too long to get me home at a decent hour. It involved a slow drive up a rough 4wd road to the trailhead, and a 15-mile out-and-back, extending the last hike I’d done there, to the farthest southwest peak in the range. If I could fit it in, it would yield views over completely new terrain.

I did the math in my head. My goal would be to return to the cafe for burrito and beer before the 6pm closing time. I was early enough that I should be able to drive that 4wd road and reach the actual trailhead with enough time for an 8-1/2 hour hike, which on decent trails would yield at least 17 miles. 15 seemed totally doable, so I drove deep into the mountains and started up the 4wd road through rolling oak and juniper forest.

Someone had left the cattle gate open. The rocky road was bone-rattlingly bad as usual – I had to creep between 5 and 10 mph, switching into 4wd at the high-clearance part. I passed a parked pickup truck, and a half mile later, a second. Damn, what a busy day here.

But nobody besides me had made it all the way to the trailhead. Plenty of water was coming down the unnamed creek, from our wet monsoon and last week’s heavy rains. I set out up the trail, and within the first half mile met two bear hunters.

They were young guys, probably early 30s, tall and fit. One looked like an urban professional, the other seemed more like a skilled tradesman. I said there always seemed to be a lot of bear sign around here, but they pointed to a tall Gambel oak nearby and said there were no acorns to speak of, the bears were likely to be someplace else. They wished me a good hike and I continued past them up the trail.

This north slope was saturated with moisture, and the creek poured noisily through its rocky gully. Where the trail led across meadows, the grass stood chest-high.

Partway up the switchbacks to the waterfall overlook, in burn scar overgrown with oak and scrub, I came upon tall shrubs I’d seen before, bearing, to my surprise, what looked like black raspberries. They were thimbleberries, Rubus parviflorus, but I didn’t know it at the time. I tried one – slightly sweet, but mostly bitter. I tried another. All in all, not enough flavor to make them appealing, and I wondered idly if they might even be poisonous.

I continued climbing the steeper and steeper slope past the overlook to the high entrance to the hanging canyon. I was intending to make short work of this first part of the hike, where most of my elevation would be gained, so I could focus more on the crest part of the hike, which consisted of long traverses with only a few hundred feet of up and down, and those spectacular views. But I’d forgotten how steep this first part is.

And in the hanging canyon, the section along the creek is always slow as you work your way back and forth over boulders and through dense vegetation. That creek bottom is the coldest place I know in the Southwest, so I pulled on my sweater. Fall had already started to color the riparian foliage down there.