Max Carmichael's Blog, page 18

July 8, 2022

Three Weeks in a Hospital, Part 1

Beginning May 13, I spent three weeks in a hospital and came close to dying. I was studied intensively by dozens of doctors from many different specialties, but they never found out what was wrong with me. This is my story, in three parts.

Mid-1990s: Dad’s DementiaBy the time he was my age, my morbidly obese father had lost the use of both hips. Like I am now, he was living in a small town far from the nearest big city. He arranged to be transported 120 miles to the state capital, again and again over a period of several years, to get hip replacements at the state university medical center.

During one of these hospitalizations, alone, far from the two sons who were his only surviving family members, he succumbed to a mysterious Legionnaires’-type disease, for which he remained confined for weeks. I remember him calling and quite lucidly describing how they had taken him to a remote, secret facility out in the country, where government doctors were experimenting on him. He sounded perfectly normal, in good spirits, joking about his predicament and how none of the staff seemed to take him seriously.

I called the nurses’ station at the hospital, and got a callback from the hospitalist treating my dad, who assured me that temporary dementia was a normal side effect of his illness.

Hospitalization takes away almost all of the freedoms and rights we take for granted in normal life. In a hospital, things are done to us, sporadically at all times of day and night, usually without our consent, by strangers who often remain anonymous, forcing us into a state of helplessness, confusion and unreality. And apparently the notion of being taken away by authorities to a remote, secret facility to be tested like a guinea pig has long been part of the collective imagination of our culture.

Friday May 6: Pain in the BackTaking a break from trying to fix my fire-damaged house and deer-damaged car, I’d traveled to Indianapolis to visit my 95-year-old mother and disabled brother for a couple of weeks, while helping them in any way they needed. I took my mom out for breakfast at her favorite cafes, did some personal shopping, and laid out a plan to clean their house and arrange for renovations.

But four days after my arrival, I reached for something in the shower and was instantly paralyzed by an episode of severe lower back pain. As usual, I managed to shuffle out to the bedroom, take a pain pill, and carefully roll into bed, sliding a pillow under my lower back to stabilize my spine.

These episodes are unpredictable, but the heavy physical labor I’ve taken on is probably resulting in cumulative strain. There at my mom’s house, I self-medicated for the next few days while doing restorative stretching and taking short walks around the neighborhood. The pain always subsides within 2-3 weeks.

Tuesday May 10 – Friday May 13: Pain in the Eyes

Tuesday May 10 – Friday May 13: Pain in the EyesBy the following Tuesday, my back pain was fading, but I woke up with a stiff neck and it hurt to move my eyes. These were symptoms I’d never had in combination before, so I just took another pain pill and continued with my plans for the day, which involved driving around the city for hours running errands.

By the next morning the eye pain was accompanied by a general headache, and my forehead felt hot to the touch, so I took my temperature. It was normal. I took another pain pill and continued normal activity, hoping the strange symptoms would pass.

But by Thursday night I was also suffering from alternating sweats and chills, and at 2 am, unable to sleep, I measured my temperature at 102.7. I Googled this combination of symptoms and was quickly led to meningitis.

The city’s largest hospital, part of the state university healthcare network, was less than 2 miles away, and I was intimately familiar with it from many family visits during previous decades. Since despite the symptoms I was still physically competent, I drove, alone, to their Emergency Department.

Through the empty streets of the dark city, from my mom’s dense, tree-shadowed residential neighborhood to the sprawling institutional tract on the near northwest side, a wasteland of sprawling buildings anonymous at this time of night. The massive hospital complex, rising to 8 stories, spans dozens of city blocks. Committing myself to this faceless kingdom, I drove between outlying wings into the belly of the beast, where the ER entrance huddled as if crushed under the weight of all that concrete and steel.

The big, characterless waiting room, so familiar from previous family emergencies, was empty at this hour and they admitted me immediately, but now my temperature was back to normal. They took me to a tiny windowless room where I was quickly seen by an M.D. who asked me to touch my chin to my chest. I did and she said “You wouldn’t be able to do that if you had meningitis!” Without any further evaluation or testing she concluded that I had a mild virus and should treat the headaches, eye pain, stiff neck and fever with tylenol and it would all go away in a few days. So I drove back to Mom’s and managed to get a few hours of sleep.

Friday May 13: Swallowed by the InstitutionMy symptoms got worse throughout Friday, until by late afternoon I was sweating through my clothes, then shivering uncontrollably. I took my temperature and it was 103.7. I couldn’t remember ever having such a high temperature and knew it was dangerous. I was now so weak that I called 911 for an ambulance. They had higher priority calls so despite our central location in the inner city, it took them a half hour to reach me.

What a difference from last night! In the strong light of late afternoon, rush hour clogged the city streets, shafts of sunlight flashing through the windows of the ambulance as it zigged and zagged on much the same path I’d driven alone not long before. Technicians rode on each side of me, taking vital signs.

At the hospital complex, we entered an unfamiliar tunnel that bored into the depths, pausing at a glassed-in security office, finally stopping at a double door where an orderly helped me into a wheelchair and pushed me down a series of hallways and finally back out into the waiting room I’d left earlier that morning. It was now packed with people.

When they checked me in for the second time, my temperature had dropped a little to 103.2. My brother had driven over to join me, and beside him, nodding in my wheelchair, surrounded by dozens of other sufferers and their families, I waited 90 minutes before being called to a room, as my fever crept back upwards.

As soon as I’d donned a gown and collapsed onto the rolling bed in the tiny, windowless room, the formidable medical apparatus switched into high gear. A nurse arrived to question me, another came to draw my blood, and a doctor arrived with more questions. I was found to be severely dehydrated and was put on intravenous saline, plus an antibiotic for good measure.

The fever and headache had left me in a brain fog, unable to fully register, track, or understand what was happening to me. But I remember a machine being brought in to give me a chest x-ray, then my bed being wheeled to another part of the hospital for an MRI of neck and abdomen, then a CT scan of my brain. Back in the tiny room probes were attached to my chest for an EKG, and more blood was drawn from the arm opposite the one that already had an IV line attached.

The doctor returned at some vague hour to admit the tests were inconclusive and they still had no idea what was wrong with me. They were trying to get a room for me at University Hospital, their research and teaching facility across town where “difficult cases” like mine are handled.

I lay in that windowless room all through the night and long into the next day, alternately sweating and shivering, awkwardly peeing into a plastic urinal bottle, waiting for someone to come and move me. Nurses and technicians continued to come and go sporadically, taking more blood, checking vital signs and the status of the IV. I had to ask each of them to turn off the bright ceiling lights as they hurried out.

Saturday May 14: University Hospital, Indianapolis: Moved to the FacilityAfter 18 hours in the Emergency Department, a new team of orderlies arrived to roll me back through the maze of hallways to the tunnel where another ambulance waited. I was driven briefly out into the bright world, and only a mile farther across freeways and more institutional tracts to the new hospital, part of an equally vast but only 6-story-tall complex.

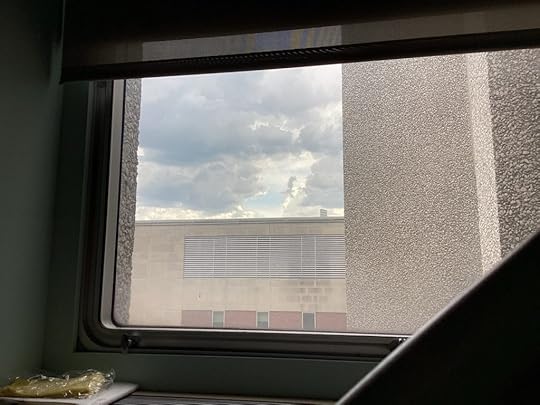

Inside another dim tunnel, another new orderly helped me out of the ambulance and into another narrow bed and rolled me through an even longer maze of hallways and elevators up to the top floor, where I was overjoyed to find myself in a large, relatively luxurious private room with a window, where I could see a slice of sky above the featureless wall of an adjoining building.

The IV had been temporarily left behind. My new nurse gave me tylenol for the eye pain, headache, and fever. Then the first team of doctors arrived to study me: Infectious Diseases specialists, with two senior MDs and a couple of interns, all standing in a semicircle around the foot of my bed.

One of the doctors explained that since I was recently arrived from New Mexico, they were concerned about mosquito- and tick-borne diseases as well as hantavirus and coccidioidomycosis, a fungal disease popularly known as Valley Fever which is endemic to the Southwest. They questioned me thoroughly and I answered as best I could considering the ongoing brain fog. They put me on a second antibiotic, doxycycline via IV, and ordered another battery of tests, some of which seemed to duplicate those I’d had in the ER.

I was in a “unit” of the hospital somewhere between intensive care and the general wards. I was left alone for hours at a time in that big, quiet room. I felt like Jonah swallowed into the belly of the whale. After the long, delirious, and exhausting night in the ER, I was feeling terribly disoriented, helpless, isolated and lonely. With his mobility problems, my brother couldn’t visit me, and I didn’t think my mom could either. Like my dad with his mystery disease, I’d suddenly and almost completely lost control of my life. There was no one who could help me or make decisions while I floated in this brain fog – or if I lost consciousness completely. Strangers were now in charge – I had no option but to trust people who didn’t know me, for whom I was just one of many short-term strangers temporarily in their care.

I’d left Mom’s place on Friday with a daypack containing my phone, iPad, and both chargers, so I called my oldest friend from high school. He’d just returned from the city to our hometown 45 minutes south, but he immediately agreed to hop in the car and come visit. It was wonderful to see him and we spent several hours chatting. A patient surrounded by strangers always feels that visiting family and friends will prove to the technicians, nurses, and doctors that other people care about you – hence they should, too.

At a time like this, there’s no substitute for the physical presence of people who know you and care about you. But if that’s not possible, the human voice is the next best thing. Email barely counts, let alone texting.

Throughout my hospitalization, I was able to talk with my mother – and one other old friend – by phone every day. And there were two others who regularly called, showing they cared and were concerned. Without these I would’ve been lost.

Sunday May 15: Hooked Up to the Machine

Sunday May 15: Hooked Up to the MachineThat weekend stay in the big, quiet room on the 6th floor was in many ways a misleading false start to my hospitalization. It had a large ensuite bathroom, so initially I was able to get up to pee, until a nurse caught me and said I should stay in bed and use the urinal.

Despite wide differences between hospital units and rooms, every room had a networked monitor and keyboard for the nurse, a small dry-erase board which they were supposed to update each shift with names and special instructions (but often didn’t), and my bed, which had a landline phone, a remote for lights and TV, and controls to raise and lower the bed’s head and foot.

The door to my room could be open or closed at my request. When it was open I always had a view of the hallway outside, along which passed a sporadic but never-ending parade of anonymous strangers, and occasionally a familiar nurse or doctor. I was given a food menu, and an orderly peeked in three times a day to ask for my meal orders – or if I could keep track of kitchen hours, I could call an order in myself.

By reading between the lines and experimenting, I gradually learned what was edible – oatmeal, yogurt, and berries for breakfast, and the turkey taco salad, the chicken quesadilla, or the grilled salmon at other times. There were a few times when meal orders simply never arrived. The nursing unit only stocked inedible puddings, but once I got lucky and my nurse went down to the late-night deli on the 1st floor and got me a sandwich.

Each meal automatically included two bottles of Ensure, which I usually ignored because I could barely stand to drink it. In retrospect I think I would’ve lost less weight if I’d drunk the Ensure.

Nurses worked 12-hour shifts, with shift change at 7 am and 7 pm. I had to learn that help was virtually unavailable – no one would respond to my calls – for an hour after shift change, as the new nurse caught up with things left undone by the previous shift.

Apart from blood draws, the new tests were slow getting started due to the weekend. But blood draws were getting harder because I’d already had so many that the nurses couldn’t find a good vein – one of them said I had too many valves. After 3 unsuccessful but painful tries, one nurse called in the “VAT team” (Vascular Access Team), a roving duo of technicians who use an ultrasound monitor to find precise locations for blood draws and IVs. They did it painlessly, and also put in a new and more reliable IV. From then on, I would beg for the VAT team, not always successfully since the nurses were often offended that I didn’t trust them.

IV sites are left in for a week or more, during which nurses try more or less successfully to use them to deliver intravenous fluids and doses of medicine, and to draw blood. They involve a tiny catheter running inside your vein, which is secured on the skin of your arm by layers of tape. As the days go by, a poorly installed IV will lose its ability to draw blood, but may remain capable of delivering fluids. After arriving in the hospital, I always had one IV site in each arm, and blood draws typically had to be done elsewhere on the arms.

By late Sunday afternoon I was having trouble breathing. First, they put me on a low-flow oxygen feed, with tubes in my nostrils. Then overnight, they arranged to move me to the Intensive Care Unit on the same floor. That was when the real hospital experience began, and my life hung in the balance.

Next: Part 2

July 4, 2022

Careful What You Wish For

My recovery plan called for a Sunday hike that would yield an incremental increase in distance and elevation from last Sunday’s hike. And to keep me motivated, it needed to avoid the popular trails near town and aim for the high mountains an hour’s drive away. My first choice was on the southern segment of the crest trail in the mountains east of us, leading to a 9,700′ peak.

But the hip pain that had stopped me from hiking 3 months ago had returned during the past week. I was proceeding on the assumption that it was only a soft tissue problem, and not a failure of my prosthesis, so I was trying to get rid of it by avoiding the activities that seemed to trigger it: hip-specific exercises, and hikes with long, steep climbs.

After a long, conflicted inner debate, I ended up reluctantly driving a short distance to a very popular trail just north of town, that would give me as much distance as I was comfortable with, on a gentle grade that shouldn’t hurt my hip.

Near town, the sky was clear and rain wasn’t forecast until evening, so I’d left my waterproof boots and pants at home. This trail starts on a primitive forest road up a narrow canyon, involving about 8 stream crossings. Some of the crossings are barely doable when the stream is low, but today it turned out to be a raging flood.

“Screw this,” I said to myself. “I’m going to climb the damn mountain. If my hip starts hurting, I’ll just cut the hike short.” So, now more than an hour behind schedule, I drove the long hour east.

The crest hike begins at the 8,200′ pass on the highway. Our recent mega-fire burned southward almost to the north side of the pass, and although our early monsoon quenched the flames, the north two-thirds of the range, including the wilderness area, remains closed.

The pass is a popular place with urbanites from Las Cruces and El Paso, and since the trail north was closed, I was expecting company on the southern segment. But despite my late start, the parking area was empty.

In fact, the trail turned out to be overgrown with thorny locust and Gambel oak, and the only tracks were from cattle. I’d encountered cattle once before along this trail, but they’d always been far outnumbered by deer and elk. This new regime echoed a worrying trend in our local mountains – livestock seem to be on the increase everywhere.

The trail climbs steadily, at a gentle grade, through the burn scar of the 2013 mega-fire. That fire had burned at high intensity over most of this area, and the remaining snags continued to topple and block the trail, which now had an abandoned feel.

But occasional views east from the deforested slopes continued to be rewarding. This is a narrow north-south range, and the eastern slope is so steep that the nearest outlying peaks are over a thousand feet lower, giving you a clear view over 40 miles of rumpled landscape to the low ranges across the Rio Grande.

As I climbed southwards along the crest, I saw a dark storm cloud forming ahead, and thought it would be great to get some weather. Be careful what you wish for!

The farther I went, the more the ground had been fouled by cattle. I had to walk carefully to avoid the deep pits made in the mud of the trail by their hooves. Saddles between peaks had been turned into churned-up mudpits, and even on steep grassy slopes the ground was an obstacle course of rain-softened cowpies. After dealing with that and fighting my way over all that deadfall and blowdown, I finally neared the base of the peak, and the rain began.

It was a hard rain, and because I’d originally targeted the trail near town, I was unprepared. Yes, I had my poncho, but I knew my feet would soon be wet in the breathable boots with their dysfunctional Gore-Tex.

But the peak was only a half mile and a few hundred vertical feet above, so I had to keep going.

Deep soil remains on these mountains from the pre-fire alpine forest, and rainwater was pouring down the slopes in a sheet flow, turning the soil into a continuous bog. And on top of that, the slopes are an obstacle course of fallen logs, many of which are so big you have to zigzag back and forth to avoid them. When I finally slogged my way to the top, where the view is blocked by spectral snags, my feet and lower pant legs were completely soaked. And I could see through the ghost forest on the north side that my return route lay under an even heavier storm.

The hike back alternated between long, apocalyptic downpours of rain and hail, with lightning and thunder all around, and brief respites of light rain. Inside my boots, cold water sloshed all the way up my ankles, and my waterlogged canvas pants chilled me and weighed me down. My hip was hurting but it was the least of my worries – I was rushing to get back to the vehicle, put an end to this misbegotten ordeal, and change into dry socks.

The hood on my cheap poncho is designed so it always blocks at least one of your eyes, so I normally carry a cap to prop the hood up. But having left that at home, I had to make do without depth perception, and stumbled a lot, my soaked boots providing no ankle support.

More torrential rain fell on the highway home. All I could do was eagerly anticipate a hot bath!

June 27, 2022

Rainy Day in the Wilderness

A long hiatus since the last hiking dispatch – more than two months – and even longer – three months – since I last ventured into our legendary wilderness area. I may explain elsewhere why I’ve lost most of my conditioning and am having to gradually rebuild my capacity. In the week prior to this Sunday, I’d done three easy hikes of up to about 4 miles and 800′ of elevation gain. All of those were on trails near town, heavily used by dog walkers, trail runners, and mountain bikers. I really wanted to dip my toes inside the wilderness, where I rarely encounter other people.

But finding a wilderness trail that would suit my recovery was a challenge. I maintain a 7-page list of regional hikes, and every wilderness hike on that list far exceeds my current capability. Doing a partial hike on any of my favorite trails would be frustrating, but I finally figured out something that would work: a partial hike of between 2 and 3 miles onto a spur trail that branched off one of my favorites. The spur trail led up over a saddle into one of the biggest canyon systems in the range, and I’d tried it last year, found that it disappeared into a jungle along a narrow creek, and decided it wasn’t worth pursuing. But the saddle itself provided a spectacular view over the big canyon, and would be a worthy destination for a short recovery hike.

I actually wasn’t confident of making it to the saddle, which would require almost 1,500′ of total climbing, but there was an intermediate spot I could use as an alternate destination if I ran out of steam. In any event, I’d get to spend time in wild habitat that would’ve changed dramatically in the weather we’d had since my last visit.

On the drive northwest from town, the mountains were almost completely hidden by rain clouds, which made me very happy. Even better, I drove through a nice little storm shortly before reaching the turnoff.

It was raining enough at the trailhead that I pulled on my poncho. The half mile of trail before the wilderness boundary was more damaged by erosion than I’d ever seen. Unusually, there’d been another vehicle parked at the trailhead, and past the boundary, on my way down into the first canyon, I encountered a lone woman returning from her morning hike. She wished me a good day and passed quickly without slowing. I stopped, turned, and said it was good to see another hiker who liked this kind of weather. “It’s just weather,” she muttered curtly without stopping or looking back.

She clearly wasn’t interested in socializing, but I continued to think about her as I continued. Short, slender, very fit, and 15-20 years younger than me, she’d been moving too fast for me to form a precise image, but she seemed to evoke several women I knew of who frequented this area. One was a hiker who lived nearby that I’d corresponded with and done another short recovery hike with years ago. Another was the “peak bagger” from Arizona that I’d tried to emulate on a difficult bushwhack last year. And a third was the trail runner whose enigmatic shoeprints I’d studied on another bushwhack three canyons to the south. I wished she’d given me an opportunity to talk more, but it occurred to me that she wasn’t prepared for wet weather – dressed lightly in a short-sleeved top and cycling-type shorts, she wasn’t even carrying a day pack, let alone a storm shell – and had likely cut her hike short for that reason.

I was surprised at how quickly only a week of rain had turned the canyon bottom into a jungle. Apparently there’d been enough groundwater to support the vegetation even before our premature monsoon. But despite today’s storm, streamflow was modest.

I was moving slower than usual, and having to take off the poncho when the rain stopped, shake it out, and repack it, only to need it again 15 minutes later when rain resumed. It was warm and humid enough that it just wasn’t comfortable to wear when I didn’t need it. But I would end up needing it a half dozen times by the end of the hike.

Having only hiked the spur trail once before, I’d forgotten how many switchbacks it has. The hike to the saddle is nothing but a series of about two dozen switchbacks, most of which don’t show up on trail maps. But I was grateful because they ensured a climb that was gentle enough for my physical condition. A friend had said my body would be eager to start climbing again, and I found that to be true – not only did I make it to the saddle, but I continued higher for a half mile to reach a better vantage point over the big canyon.

It was raining harder up there on the ridge, so the view was too hazy to savor. But it felt great anyway!

Since I wasn’t rushing to complete a marathon hike to a remote destination like so often before, I felt in no hurry on the way down, and was able to stop many times to appreciate the little things, and really enjoyed this hike as a result. It’s precious to be immersed in this arid habitat during such a wet period. But also, after being in regular touch with friends in distant cities, I was reminded again of how lucky I am to live in a place like this, where a huge mountain wilderness area, with a mostly intact ecosystem virtually free of invasive species, is only a short drive from my home. And because of its size and our low population density, I typically have it all to myself!

April 21, 2022

Protected: Bathroom Wall Accessories

This content is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

April 11, 2022

Tantalus & Sisyphus Go For a Hike

As usual, this Sunday’s hike was conceived with complicated and conflicting desires. I was still reeling from last weekend’s accident, so I didn’t want to drive far and risk returning in the dark. I was worried about the recurring pain in my hip, so I didn’t want as much climbing and rough surfaces as usual. But to give my hip a break, I’d skipped my short midweek hike and was also reluctant to wimp out and do an easy hike on the weekend.

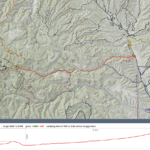

I ended up targeting a trail about 45 minutes from town that I’d had on my list as a lower-elevation winter hike, but hadn’t tried yet, since it didn’t seem to offer as much elevation gain as I usually craved. I’d already located the trailhead along the highway east of town that goes up a rural valley toward remote recreation areas, and I’d observed from the faint tread that this trail is little used. It climbs up a series of canyons to the crest of the low forested mountains that trend from east to west north of town, where maps show that it meets the Continental Divide Trail and ends at a forest road I’d spotted from a crest hike last year. I wanted to try for the CDT junction 8-1/2 miles in, but that would be a 17 mile round trip with nearly 3,000′ of elevation gain, and I didn’t know if my hip was ready for it.

Online maps disagree as to the exact route of this trail. I vaguely remembered reading an online account of a partial hike that said it was confusing and hard to follow and there was a corral or cabin in one of the canyon bottoms. But in my usual hurry to hit the road I failed to bring a map, trusting on my routefinding skills.

The day was forecast to be clear with a high of nearly 80 in town. It was in the low 50s as I left home, but when I reached the trailhead I took my sweater off.

The first thing I encountered was a confusion of trails up a broad, dry floodplain forested with large, old pinyon, juniper, and oak and rumpled with flash flood debris. I just assumed the trails would all converge upstream and took the most direct routes. After a quarter mile they did converge and began climbing the left slope. But that slope turned out to be laced with a dense network of intersecting trails, like the diagonal grid of a chain-link fence, and they all showed heavy use, so it was initially hard to figure out which to take. Most were clearly animal trails, but I saw no cowshit so I was initially mystified.

But I did begin to notice human footprints, and was soon able to pick out the hiking trail from the animal trails. Then, when the trail dipped back into the canyon bottom, I found clearings of disturbed ground covered with piles of horseshit. Horses are not generally allowed to range free, so I figured this must be a rare enclave of feral horses.

The trail began climbing steeply, and two miles in from the trailhead I came to a stock gate in a narrow saddle marking the watershed between this canyon and the next. The gate had been left open by the recent hikers who had left their footprints on the trail, so I reclosed it. We think of hikers as environmentally sensitive people, but this hike would yield ample evidence they can be as insensitive and irresponsible as your average urban consumer.

Through the gate and over the saddle I got my first and only view into the next canyon. The trail was heading down the north slope of a small, densely forested basin, at the far end of which I could glimpse some kind of small grassy clearing. The trail quickly deteriorated into a very steep, rocky erosional gully, in which I slowly and carefully tried to avoid stumbling down a couple hundred vertical feet through dense scrub. I began seeing cowshit, and at the bottom of the basin I entered a thoroughy trampled and overgrazed area with a fence, corral, and a small, muddy water hole. From there I followed a broad cattle trail to a running stream trampled by cattle and choked with algae, and another stock gate. I was pleased and surprised to see so much water in the canyon, but in general, this was turning into a fairly depressing hike.

Past the gate, the trail became a vehicle track. I kept following it through forest and out into a big grassy meadow, but I was worried that like much of the CDT, this trail would turn out to follow a road the rest of the way.

At the upper end of the meadow lay a cabin and a series of old but intact corrals and sheds. The cabin looked maintained and its door was tightly wired shut so I didn’t try to get in. But I could see through a window screen that it was clean and fully furnished inside. I later learned that it’s still used by the family that ranches the canyon.

Beyond the cabin the trail continued to follow an old road, back and forth across the algae-choked creek and its trampled, overgrazed banks, until it finally began to climb a steep, rocky slope and narrowed into a real hiking trail again. The footprints of three other recent hikers continued there, but they were dominated by the hoofprints of cattle.

We didn’t really get that much snow over the winter, so I was surprised to find more water draining from the slopes into the creek here than I’d seen anywhere else in our region.

Continuing up the canyon, I finally emerged into a stretch with more exposed bedrock and clearer running water. I came upon a crumpled piece of toilet paper on the trail, and continuing, saw a scatter of toilet paper on the ground at the foot of rock outcrops above the trail. These recent hikers were truly jerks, failing to carry out their paper waste, leaving it to be scattered by animals and found by later visitors.

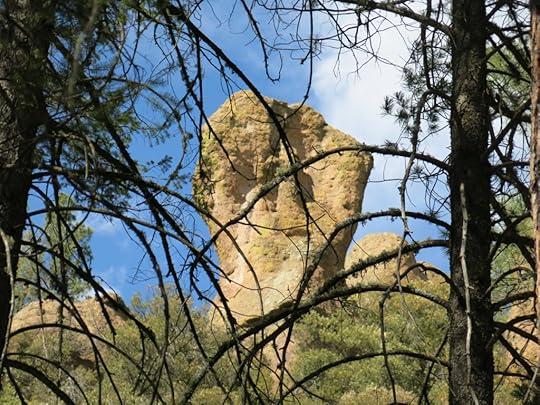

I was now in a stretch of canyon lined with huge boulders, cliffs, and impressive rock outcrops, but immersed in dense forest, I could only catch glimpses through the tall ponderosas, oaks, and alders.

Four or five miles in, I came to a junction with a trail that led into the next canyon south. My trail so far had been fairly clear of logs but showed no sign of recent maintenance. But beyond the junction, I encountered a few shrubs along the trail that had been recently chopped. That isolated trail work only lasted a few hundred yards, so I figured the crew had come up the side trail from the other canyon and only worked a short distance in this one.

Flies – the size of house flies – had been visiting me occasionally all the way up the trail, but had never become a nuisance, in contrast to the small flies or gnats that had plagued me in Arizona recently. I associate these larger flies with livestock and was relieved not to need my head net.

The rock formations just became more and more spectacular the farther I climbed up this long canyon, but remained tantalizingly hidden. I figured I’d gone well over 6 miles at this point and was still stuck in the canyon bottom. When would I start climbing to the crest? My hip wasn’t bad yet, but I didn’t want to reach a tipping point where my return hike would become really painful.

As much as I hate perpetuating colonial culture, I couldn’t help mixing up the myths of Sisyphus and Tantalus, kings who were punished by the gods in ways that resonated with my situation. Not that I really think I’m being punished – the life of all true seekers is hard as we refuse to fit into the dominant mold of our culture, rejecting the career, the steady job, the marriage, the kids, and the endless upward climb of consumerism. But today I felt continually tantalized by brief glimpses of majestic rock formations, and condemned to an endless climb.

The last couple of miles were especially hard as I sensed the crest getting near. The canyon narrowed and seemed shallower. I was now in the upper elevation mixed conifer forest with firs and tall old-growth Gambel oaks. My hip was beginning to complain, but surely I was nearing the top?

I wasn’t. The trail turned left, then right, and just kept traversing up a gradual slope, and trapped in the dense forest I had no way of orienting myself in the landscape. Human footprints had ended much earlier – the recent hikers had only gone about four miles in – but cattle were using this trail all the way up. At this point they were the only users. Nor had there been any maintenance in a long time – I found logs that had lain across the trail for at least a decade.

Eventually, instead of cliffs and rock formations, I began to glimpse blue sky through the trees above, and believed I was nearing the top. But after a few more turns and long traverses, I found myself again in the bottom of a narrow, rocky canyon. There I found a rusted, empty water trough half-buried in debris. And after crossing the canyon bottom again, I faced the steepest trail I’d seen yet. Surely this must be the final climb? I’d been hiking for five hours, which would normally take me more than ten miles. But coming this far, I just had to see where the steep trail led.

It turned out to be one of the steepest trails I’d ever climbed. I estimated the grade at 35%, and to prove I don’t normally exaggerate, when I got home I measured it on a topo map and found the average grade is actually 36% on that stretch.

But nearing the top of the steep stretch, I suddenly emerged into a zone of strong wind, and was convinced I was nearing the crest, where wind would strengthen due to the funnel effect. And after traversing an overgrown burn scar, I finally came upon a fence and the dirt forest road. I’d seen no sign of the CDT junction – I’d misinterpreted the topo maps.

I was now behind schedule, my hip was hurting, and this overgrown burn scar offered little in the way of views and was no place to hang out. But I knew I’d achieved a serious hike and was proud of myself. Knowing the descent would be even harder on my hip, I took a pain pill and began the long slog back, most of which would mercifully be downhill.

Before reaching the overgrazed canyon bottom, I did finally encounter some small flies, but they never became bad. I’m always intrigued by the ecology of things like this. Why are they localized, and locally a problem?

The day had gotten windier, and I realized that despite its frustrations, the wind and shade of this hike had been an escape from our spring heat wave in town.

I reached the trailhead 9-1/2 hours after I started. I’d made a lot of brief stops, but it had to have been a long hike. When I plotted and profiled it back home on a topo map, I found it had totalled 17.3 miles, with 2,932′ of accumulated elevation gain. Coincidentally, the forest road where I turned around is only a quarter mile from the point I reached last year on a 19-mile hike from much closer to town. So I was only a quarter mile from connecting the two hikes.

April 4, 2022

Bad Luck and Trouble

Trying to maximize the time available for my Sunday hikes without rushing and stressing out, my weekend schedule is tight, and I’m still having trouble adjusting to daylight savings time. This weekend I set my alarm to go off early, but still ended up getting a late start, because I couldn’t decide where to go. I really wanted to return to the range in Arizona with a trail that climbs through granite boulders – it’d been almost a year since I’d been over there – but it comes at a high cost.

I burn a prodigious amount of energy on these hikes, and end up starving afterward. But it’s a two hour drive, and there are no restaurants along the way, so I need to end the hike in time to get back home at a reasonable hour. I never like to drive home in the dark anyway, because of the chance of deer on the road. Those time constraints generally result in shorter hikes than I can do closer to home. But for other reasons, the cost of today’s hike was much higher than usual.

The day was forecast to be partly cloudy with a high of 70 at home. Perfect hiking weather. But I wasn’t thinking about elevation and aspect – the trail starts 1,000′ lower than home and is fully exposed on a south-facing slope for most of the way.

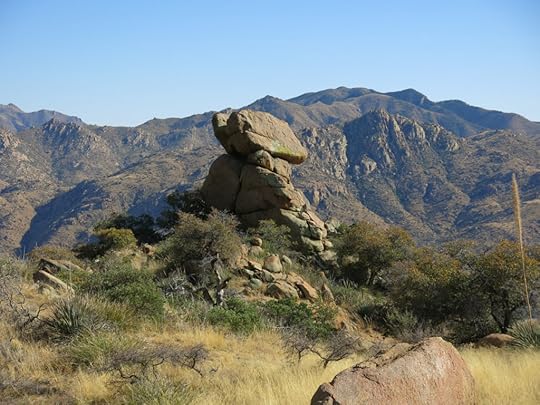

One reason I like this trail is that it’s a steady 4,000′ climb to the crest. But since most people prefer an easy hike, trails in this range are intended to start at the paved road on top and end at the bottom, where there is no marked trailhead. You have to know the turnoff onto a high-clearance 4wd track that meanders a few hundred yards into the foothill scrub, and then you have to know where to start the trail, a few hundred yards beyond the end of the track. I figured all that out on my first visit.

Nobody had driven that 4wd track recently, but it’d been fully trampled by cattle. The boulder-strewn base of the mountains alternates between meadows, dense scrub, and giant old Emory oaks, and the trail meanders between them while climbing gradually into the complex topography of the foothills. I could hear the cattle before I saw them – they were grazing a grassy basin to my left – then while stopping to stretch I was surprised by a cow and her calf emerging from the oak scrub a few yards away.

This is generally a good trail, and a very beautiful one, but it’s seldom used. One large man had walked the first mile or so recently, but his footprints ended soon. Even the cattle seem to stick to the foothills and never venture higher.

Flies were bad and I had to pull on my head net shortly after starting. Small flowers brightened the trail, and the Emory oak leaves were turning. We think of deciduous trees as changing color and losing their leaves in fall, but the Emory oak does this in our windy season of March and April.

The day felt hot from the beginning. My memory of this place was rusty, and things had changed in the eleven months since my last visit. The steady climb that yields spectacular views is exhausting, and last summer’s wet monsoon had resulted in overgrowth of the trail by grasses and shrubs. Near the bottom it was thorny mesquite that scratched my hands and made me especially grateful for thorn-proof pants. Since virtually no one besides me hikes the full trail, grasses had obliterated much of the tread and hid rocks that kept throwing me off balance. Game trails often had more tread than the hiking trail, so I really had to rely on memory and cairns, which were themselves sometimes buried in overgrowth.

Fortunately the flies disappeared beyond the foothills – hopefully they were localized around the cattle. But it seemed to take much longer and require much more effort than expected to reach the midway point, a saddle in the ridge that stays to your right during the climb. Since the entire trail, ending at the crest highway, is only a little over 6 miles – shorter than my usual Sunday hikes – my plan had been to add a mile or two on a side trail. But I was so fatigued by the halfway climb I wondered if I’d even be able to finish this trail.

The second segment of the climb to the crest runs through completely different habitat: a unique mixture of scrub oak and fir forest between outcrops of white rock. The vegetation is so dense you know it’s the product of wildfire and is now overdue for another burn, but in the meantime it’s a great place to visit. But in dense vegetation, protected from wind, it felt like it was 80 degrees, and my head net went back on because the flies in that area were terrible.

Entering the shadowy old-growth fir forest near the crest I got a second wind. The second milestone on this trail is a tiny saddle where it crosses to the north side of the crest and enters dense, cool fir forest – the third completely different habitat adding to the appeal. It’s a 3,200′ climb to that saddle, and while traversing upward on that north slope you occasionally get glimpses through the firs of the vast Gila River Valley 5,000′ below to the north.

Shortly after starting that traverse I heard the voices of a young couple hidden in the trees above the trail. Like most people, they’d walked down from the crest highway and were just hanging out. Three quarters of a mile farther, near the 8,700′ high point of the trail, I heard kids yelling and screaming on the little peak above – more people who’d simply walked over from the crest highway – and that made up my mind about what to do next.

Just below the peak there’s a signed junction – a trail that’s sort of the mirror image of mine, climbing from the northern foothills. I couldn’t remember anything about this trail, but I figured I’d explore and use it to add mileage and elevation for the day.

It surprised me by dropping very steeply through more dense fir forest, in a seemingly endless series of switchbacks, the most I could ever remember, some of them only two or three dozen feet long. Due north of me I could see a white rock spire and knew there had to be a saddle between me and it. I figured that would be my turnaround point, but it seemed to take forever to get there, in 600′ of descent that I would then have to climb out of.

When I finally reached that saddle in a small sunny clearing, it was hard to leave it. But my hip was hurting and I couldn’t afford to delay.

I counted the switchbacks on the way up – 32! But they actually made the steep climb tolerable. It was late enough now that everyone else had left and the only sounds were from wind and birds.

Heading down the south slope from the junction saddle, my hip was so sore I took a pain pill and began favoring that leg. Precarious footing on loose rocks, swarms of flies – but in partial compensation, those endless views!

As expected, I made much better time going downhill, but in the foothills, where tread was often buried under grasses, I first got confused, and then got completely lost.

In a level patch where grassy slopes declined on three sides, there was a nice big cairn, but nothing more that looked like a trail. Why hadn’t I noticed and marked this spot on the way up, like I usually do if the way seems confusing?

I spent 20 minutes scouting far and wide for trail in all directions beyond the cairn, but could find no sign of trail. I was now running late, so I said “Screw this, I’ll just bushwhack.” Far below I could see a little rocky peak. I knew the trail crossed a grassy saddle just before it, then traversed the left side. If I just headed straight down I should intersect the trail somewhere.

With the deep grass hiding sharp rocks and drop-offs, it was slow and hard going. After another 20 minutes, I came upon another cairn and the continuation of the trail. I figured I was now a half hour late.

I was in one of the prettiest parts of the trail when a golden eagle flew over, hazed by a small, screeching hawk. I couldn’t get a picture because they were directly in front of the setting sun.

Further down, I found the cattle in exactly the same place as 8 hours ago.

The drive home was uneventful until dusk, when the highway home climbs through the foothills of the low mountains south of town. I’ve occasionally found deer standing in the road there and am always paranoid. I did pass a small group standing off in the grass on the right, but they didn’t even raise their heads as I drove past.

Then, about 10 miles outside of town, when visibility was getting poor, I suddenly noticed another small group standing off in the brush to my right, grazing peacefully. I was driving the speed limit, 65, but since they weren’t on the move I figured I’d make it.

But just at that moment, one doe darted directly in front of me, the length of her body slamming against the full width of my car’s grille, and her sideways momentum combined with the forward momentum of my car threw her limply all the way across the highway to my left.

She was killed instantly, and parts started flying off the front of my car. In shock, I slowed and pulled over and got out to check the damage. The car seemed to be running fine, but the grille was gone, the front frame and hood were slightly buckled, the radiator fan was just hanging loose behind the bumper, and the headlights, glass completely gone, were barely hanging on by their wires.

It was getting dark fast, and I focused on just getting home, especially since my headlights were useless. Approaching town I started to smell anti-freeze and knew I was on borrowed time. I took a detour on back streets to avoid cops. The temperature gage still looked normal. But a block from home, the engine emergency light came on and I noticed the temperature gage was pinned in the red. I managed to roll up to the curb in front of my house just as smoke started pouring out from under my buckled hood and I turned off the ignition.

I was still in shock, but I knew this was an overdue initiation to rural driving, and I was very lucky. A guy in his 20s had recently died just outside of town after swerving to miss a deer, and one night in the Sierra Nevada of California, my dad rolled his car, was thrown out into a field, and broke his collarbone after swerving to miss a deer. More recently, one of my oldest friends hit a buck while driving home late and, like me, barely made it home with his crippled car.

April 2, 2022

Protected: Adjustable Height Desk

This content is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

Protected: Bed Restoration

This content is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

March 28, 2022

A Walk in the Park

Nothing exciting or spectacular to report this week. Sunday’s hike was a personal milestone in that I was finally able to return to the highest-elevation trail in my regional circuit. It crosses a 10,000′ peak, traversing a densely forested north slope that retains deep snow late in the season. Our unusually cold winter finally broke during the past couple of weeks, so I guessed that I could now handle whatever snow remained up there with my normal 3-season boots.

Over the years, as I increased my capacity for longer hikes, I’d encountered a catastrophic blowdown on the far side of the peak which obliterated the crest trail. Becoming accustomed to bushwhacking and routefinding, I’d fought my way through that blowdown, and through a half mile of wildfire deadfall beyond it, eventually reaching a saddle marking the crest trail’s junction with feeder trails coming up major side canyons. Out and back, that hike amounted to almost 20 miles round-trip on the crest trail, which felt like quite an accomplishment. Not only did it include climbing over, under, and around the blowdown and deadfall. I also believed I had that part of the trail to myself – I never saw evidence of other hikers making the effort I was making.

The trail starts at an 8,200′ pass and traverses alternately across east-and-west-facing slopes, climbing steadily through exposed burn scar high in the sky, with long views across the southern landscape, until it reaches intact stands of pine and fir at the top of the peak. It crosses the peak through beautiful alpine meadows and groves of old-growth conifers, passing near a famous fire lookout which is the destination for most hikers.

The temperature in town was forecast to reach the high 70s, and I found it warm enough at the pass to take off my sweater. The sky was mostly clear with a few wispy clouds. It can be windy up there on the ridgeline, but was fairly calm during the climb.

Shortly after entering the forest on the flanks of the peak, I saw another hiker coming down the trail toward me. This stretch of the trail to the fire lookout is the most popular trail in our region, because it’s the highest elevation – hence coolest – hike accessible to the nearest low-lying cities – Las Cruces and El Paso. So I always expect company here. We stopped and had a lengthy talk. In his late 20s or early 30s, tall and slender, he was from California and completely unfamiliar with local culture and habitats. He couldn’t get over how much brush and deadfall he found in our burn scars – he’s apparently accustomed to easy, groomed trails.

He’d come prepared for backpacking and spent the night on the peak, returning in frustration after failing to find water up there. He shook a floppy, empty water bottle at me and said his filter had become clogged with melting snow. But he was impressed with our “real wilderness” – as opposed to what he was used to farther west – and wanted to return for a longer stay.

Leaving the popular trail behind on the far side of the peak, I was prepared for my hike to begin at the big blowdown, which no longer seemed like an obstacle for me. Imagine my surprise when I reached the saddle and saw an opening had been cut through those giant ponderosa logs!

A trail crew had arrived some time after my last visit, toward the end of our monsoon in early September. My first reaction was actually disappointment, and my disappointment grew as I discovered they’d logged and brushed almost all of the trail from the saddle to the distant junction. What had become a fun obstacle course was now like a wilderness superhighway.

Wildlife was sparse on the ground and in the air. It was too early for migrating birds, and I saw no deer or elk. With the trail clear, I had no trouble reaching the junction saddle in good time, so I stretched out on the ground. The temperature was still mild, but the sky was being covered by a thin cloud layer, and wind was picking up.

Climbing from the saddle exposed me to a fierce wind out of the southwest, and I had to snug the chin strap of my shade hat. Wind and cloud cover dropped the air temperature but the gradual climb back to the peak kept me warm. Still, the higher I climbed, the stronger the wind became.

Nearing the peak, my acculated elevation gain for the day exceeded 4,000′, and I could definitely feel it. Remaining patches of snow were unstable enough to throw me off balance several times, so I had to focus on staying calm and composed. Then, descending out of intact forest on the other side, the wind reached gale force, nearly blew me down, and tore my hat off despite the chin strap. I was able to chase it down and had to carry it for much of the remaining descent. It was now cold enough to require the sweater.

About halfway down, I spotted the smoke of a wildfire, 20 miles west and a few miles north of the highway I’d be driving home. Then I came upon a mysterious piece of blue synthetic fabric about two feet long, labeled “Mission Enduracool.” It had obviously been dropped by the young hiker from California. I stuffed it in an empty pocket. At home I learned it’s some sort of high-tech “cooling towel”, apparently used by athletes. After decades of running, hiking, and backpacking in the Mojave Desert, I’ve never heard of such a thing. Wonders will never cease, and it remains a mystery why someone would need it at high elevation in late winter.

Then, only a few hundred yards before the trailhead, I came upon that floppy water bottle. Yeah, I know, I’m prone to losing things on hikes, but I generally make the effort to go back and retrieve them. This California hiker was shedding gear right and left, and he didn’t have the wind for an excuse – it started long after he would’ve returned to his vehicle.

All in all, it was a hike on thoroughly familiar ground that offered nothing new, but still felt like an accomplishment – after a long winter, the high ground was again accessible, and from now until next winter I’d have a lot more choices in my hiking routine.

March 21, 2022

Bushwhacking the Last Frontier

It hurts to write this. Standing at my desk, with my laptop and papers raised on cardboard boxes because my back pain won’t let me sit, an ache throbs up the back of my legs, and I’m so exhausted I can barely think.

I’m not sure why – I’ve done much harder hikes than the one I did yesterday. It may be allergy – I had my first bad attack of the current season a few days ago, my eyes have ached and watered since, and a headache kept me awake much of last night. These things will pass.

I’d been wanting to get back to the range of canyons in Arizona near the Mexican border, but didn’t want to repeat the hikes I’d done there recently. I finally decided to try a trail I’d been avoiding because according to the description, most of it would be easy, and the rest might be impassable. I wanted to reach the crest, which would reward me with 4,000′ of elevation gain, but I was actually looking forward to some bushwhacking. It would be a final frontier of sorts – the last major trail on this side of the range that I hadn’t hiked yet.

Our weather was getting cooler, but under a clear, sunny sky at lower elevation than home, I hit the trailhead with my sweater off. Climbing up a long canyon with spectacular rock formations and exotic vegetation, it’s the most popular trail in the range, so there were 8 vehicles parked in addition to mine, but I knew most of them would be birders, confined to the first mile or so. And that’s what I found – I passed all eight groups, including many young people, in less than a mile and a half. Nobody else was actually hiking the trail.

Birders are seldom friendly – they view strangers as annoying interruptions in their competitive hobby. One older man was actually hostile – when I wished him a good morning, he scowled and said “Is it morning? I’m not so sure.” I checked my Arizona-adjusted watch and said we still had an hour and a half of morning left. His wife smiled but he kept scowling as I passed.

As I left them all behind, my sweat began attracting flies and I had to pull on the old head net.

The trail description claims it’s level for the first four miles, but I found that it climbed 1,100′ in that distance, which is hardly level. Being popular, it is much better maintained than trails back home, at least in the first few miles. Virtually all of it lies within federal wilderness. The rushing creek, draining from snow still clinging to the crest, is lined and clogged in many places with debris from floods after the 2011 wildfire, so the trail is occasionally diverted high upslope.

But I do love the riparian canopy here, visually dominated in winter by the leafless white sycamores, with oversize yuccas and agaves along the trail. The map and trail description mention an apple tree about three miles in from the trailhead, but I never found it, enjoying maples and dark groves of majestic cypress instead.

At the four-mile point I reached the noisy confluence of two creeks. The main stem came down from the right, draining the vast upper canyon whose rim I’ve hiked many times. But the trail continued straight up a side canyon. According to the trail description the next stretch was in worse condition, but I found that a lot of work had been put into logging, brushing, and grading it during recent months. It was very steep and much of it was rocky, but the only thing slowing me down was my stamina – I had to stop more often than usual to catch my breath.

One strange thing about this tributary creek was its color. Where it was rushing it looked clear, but where it pooled, it was a pale, opaque turquoise.

Narrow, hemmed in by cliffs, the side canyon climbed 1,500′ in the next two miles. Patches of snow still clung to slopes above, and I was excited when I reached a small stand of aspens.

But just beyond the aspen grove, the creek disappeared underground, and I emerged in a small basin where several side drainages converged. The maintained trail ended there, and the only thing that beckoned me forward was a pink ribbon above a brushy, trackless slope which had burned intensely in the old wildfire.

I followed a series of ribbons through the brush and bunchgrass for a few hundred yards, and came to a chaotic erosional gully choked with boulders and logs from above. The ribbons continued across it into a thicket, so I scrambled over, and began fighting my way through dense brush, much of it thorny locust, up the opposite slope in search of more ribbons. I’d brought the map with me but was trusting to the ribbons now.

Several hundred yards up this slope the ribbons ended, but the brush remained thick. High over my right shoulder I could see the snowy crest, still a thousand feet above, where I’d hoped to end my hike. But I wasn’t going to fight my way through locust all the way up there, and that log-and-boulder-choked gully would be no easier.

A more attainable goal loomed ahead of me: a lower ridgeline where I knew there was a trail I’d approached from the opposite direction more than a year ago. Somewhere in my current vicinity there was supposed to be a spur trail that led up there, but it seemed to be buried or hidden in thickets. I saw a minor spur of the mountain ahead of me, across a minor drainage, that was sparsely forested but showed no thickets, and might be a direct route to the ridge. Getting there was not easy – fighting through more thorns, climbing over logs, descending steep boulders, clawing my way up a loose slope – but as I approached, I saw a trail on that spur where no trail was supposed to be.

When I reached it I found it was just a game trail that quickly disappeared, and I found myself ascending a knife-edge ridge choked with sharp rock outcrops, random deadfall, and more thickets. Looking at the surrounding landscape, I saw I’d picked one of the more difficult routes to the high ridge, but I’d committed myself, so I kept climbing. After about 45 minutes I’d only gone about an eighth of a mile, but I suddenly emerged on the spur trail and felt I had a real chance at reaching the ridgetop.

I’d be cutting it close. Bushwhacking had used up a lot of time, and as usual I wanted to finish the hike in time for beer and burrito at the cafe. And although the spur trail had good tread, it was overgrown with thorns and blocked by huge logs and deep, debris-filled gullies. I even had to carefully cut steps across a long, steep patch of snow, where I found footprints from weeks or months ago, evidence there was somebody in these mountains as crazy as me.

Soon enough I reached the trail junction on the ridge, and got my reward – a new view to the southeast of the range and the mountains of Mexico beyond.

The wind was howling up there and I had to hurry back. I didn’t want to repeat that bushwhack and wondered if I might be better off taking the other trail back, but checking the map I could see that route would be at least a mile farther. I thought I might return on the spur trail as far as the tread lasted and see if I could find a shortcut to the main trail.

In the event, the spur trail disappeared high above that thicket where the ribbons had led me earlier. It ended at a sheer-sided gully ten feet deep, so I had to fight my way down through thorns to the big boulder-and-log-choked gully above my earlier crossing. This was as hard as any bushwhacking I’d done, but I finally reached the pink ribbons and the trackless traverse that led me to the small basin and the resumption of the maintained trail. I figured I now had just enough time to reach the cafe, if I walked fast down that steep trail.

I hadn’t seen or heard much wildlife on the way up, but just before reaching the confluence of creeks, I heard a sharp, catlike cry. Then, under the canopy of the lower canyon, two spotted towhees dashed into a bush at my right, then a woodpecker landed on a tree trunk at my left. Shortly after that I came upon a solitary whitetrail doe that merely sidestepped up the slope a few yards as I passed her.

Dark clouds had been blowing over. I finished my first beer while waiting for the burrito, then drank another half glass, so I had to stay in the motel that night. Heavy rain began to hammer the roof after dark.

In the morning, I saw a dusting of new snow on the upper slopes. Rain fell sporadically during the drive home, and it was actually snowing lightly when I entered my hometown.