Peter Stothard's Blog, page 17

November 10, 2015

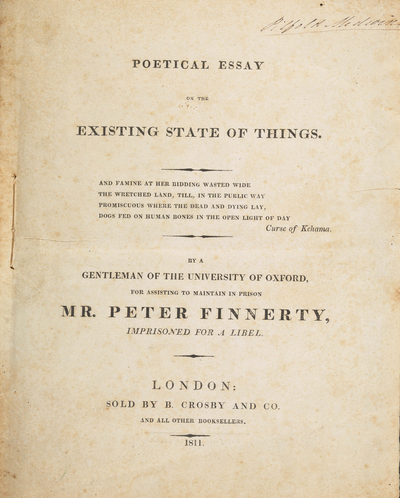

Shelley���s Poetical Essay goes back to Oxford

Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

By MICHAEL CAINES

Destruction marks thee! o'er the blood-stain'd heath

Is faintly borne the stifled wail of death . . . .

Every now and then, somebody discovers a manuscript previously thought lost ��� or previously altogether unknown. If there is any unpublished material to be discovered, however, manuscripts are usually the form they take. By contrast, it is "extremely rare for printed books of any period to be rediscovered", as Henry Woudhuysen has noted in the TLS, especially "after an absence of 200 years".

Professor Woudhuysen was writing about just such a rarity: Shelley's Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things, which survives in a single copy. And which you can now, at last, read for yourself . . . .

As every radical schoolboy and atheist schoolgirl knows, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley enjoyed a brief but notorious career as an undergraduate of University College, Oxford: he was expelled in his first year, following the publication of tract provocatively titled The Necessity of Atheism. (Even more provocatively, copies were sent to heads of colleges; one don is said to have burned a copy on the spot.) This was not, you'll be unsurprised to hear, an isolated incident.

Oxford was then a "lethargic, conservative intellectual community", James Bieri has written, "largely confirmed in the prejudices of the wisdom of 'Kingly power' and the dictates of the Church". Within weeks of his arrival, Shelley had produced Posthumous Fragments of Margaret Nicholson, a hotch-potch that included lines such as "Monarchs of earth! thine is the baleful deed, / Thine are the crimes for which thy subjects bleed", as well as a rhapsodic Epithalamium for those French regicides (of different eras) Fran��ois Ravaillac and Charlotte Corday. Bieri quotes a conservative reader's view that the book was "stuffed with treason".

Shelley also appears in the "ultra-liberal" newspaper the Oxford Herald as one of four contributors to a fund established by the radical politician Sir Francis Burdett in support of an Irish radical journalist, Peter Finnerty. This was after Finnerty had been imprisoned (and not for the first time), for reasons outlined at the outset of Henry Woudhuysen's essay from 2006, "A Shelley pamphlet come to light"; Finnerty was also made to stand in the Dublin pillory, "where a large crowd of sympathizers kept him company". Such were the wages of sinning against ��� or rather, trying to stand up to ��� powerful men such as Lord Castlereagh, the then Secretary of State for War.

Shelley produced a pamphlet to raise funds for Finnerty, the aforementioned Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things. While scholars have known of it since the 1870s, however, their efforts to locate it have proved fruitless. The seemingly sole surviving copy only came to light by accident, as it passed, unrecognized, into the hands of the antiquarian book trade.

Since 2006, the Poetical Essay has remained all but invisible to the general public, bar the odd exhibition. Michael Rosen, for one, has found this state of affairs perplexing. Why has such an important work remained hidden from view? "We must wait", he has written, "till . . . one of our libraries finds the money buy it."

That has now happened. Tonight the Bodleian Library in Oxford (where else?) unveils what is apparently its 12 millionth book, with Vanessa Redgrave and Simon Armitage (both of whom have accepted the most un-Shelley-like accolade of a CBE) among the distinguished celebrants. And it's safe to say that this is a moment to excite Shelley scholars, too. "I didn���t think in the course of my career studying Shelley", Michael Rossington has said, "I���d ever be in the position to read this work."

What exactly has the Bodleian acquired? Not only 172 lines of early Shelley but a preface, an epigraph from a poem by Robert Southey (The Curse of Kehama, 1810), and a dedication to Shelley's first wife, Harriet Westbrook (the first printed reference to the woman with whom Shelley would, in the same year, elope). The name scrawled at the top of the title-page reproduced above shows that the book belonged for a time to Shelley's first cousin once removed, the superbly named Pilfold Medwin.

And the poem? Judge for yourself. As every radical, atheist and Romantic with a web browser will soon be able to do, courtesy of a Bodleian website dedicated to the Poetic Essay, I read it this afternoon. So I think I now have a hint of how Professor Rossington feels; lines such as "Kings are but men" will remind the experts and aficionados of similar sentiments elsewhere expressed. One of my first impressions, however, is that Shelley might as well have written on the title page "Do not open until 2015" as "on the existing state of things". Shelley writes of the "Millions to fight compell'd, to fight or die", who in "mangled heaps on War's red altar lie". He writes of the gulf between flaunted riches and helpless poverty: "Is't not enough that splendour's useless glare, / Real grandeur's bane, must mock the poor man's stare". He writes of Castlereagh (although not by name) and those in power who make life worse for those altogether without it, the "cold advisers" who "coolly sharpen misery's sharpest fang".

The universal strain then finds expression in a globalized vision of imperial iniquities ��� of colonialist chiefs "hot with gore from India's wasted plains" (not exactly the Andrew Roberts view of history), and of "The Asian, in the blushing face of day, / His wife, his child, sees sternly torn away". There is even, at the end, in one of the notes at the end of the poem, an allusion to a government minister's speech during the most recent Session of Parliament, showing how Shelley, the son of an Whig MP, saw the need to keep up with the political times.

In poetic terms, the Poetical Essay adopts some thoroughly conventional manoeuvres that the young Shelley has more or less mastered, in the form of the rhyming couplets that the "essay" part of the title conventionally promised, the rhetorical posturing ("Yet let me pause . . .") and the ready stock of abstractions that he would press into use in later years, too. Take Queen Mab, another politically risky poem begun (not by no means finished) in 1811, for an example more sophisticated in terms of verse and vision.

In some alternative, counter-factual dimension, some less scandal-mad version of this Oxford poet inherited his father's title, and probably his seat in parliament, and every last piece of evidence for a versifying youth went on the fire. In this dimension, the Bodleian is doing fine penance by taking good care of those same fiery works.

November 9, 2015

Christopher Duggan

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Christopher Duggan, who has died aged fifty-seven, was a valued contributor to the TLS, writing with elegance and insight on twentieth-century Italy. His particular area of expertise was the Fascist period ��� he was awarded the Wolfson Prize for History for Fascist Voices: An intimate history of Mussolini���s Italy (2012), which the TLS reviewer called ���an impressive and very readable work���. But he ranged more widely, and wrote eloquently about literary figures such as Gabriele d���Annunzio.

Duggan���s first review for the TLS, in 1985, was of a book about General Carlo Alberto dalla Chiesa, the anti-Mafia Prefect of Palermo who was assassinated in September 1982. Duggan concluded his review: ���If the present war against the Mafia is to be effective, the testimony of such men as [the informant] Tommaso Buscetta needs cautious evaluation. Excessive zeal fosters feelings of victimization, and such feelings have their roots deep in Sicilian history���.

Christopher Duggan in the TLS:

"Under a volcano": a review of The View from Vesuvius by Nelson Moe (February 14, 2003)

Page 1 (scroll down to see text)

Page 2

"Divergent futures": a review of The Emperor of Ice Cream by Dan Gunn (April 3, 2015)

November 8, 2015

Eric Gill at the Old Truman Brewery

By BENJAMIN POORE

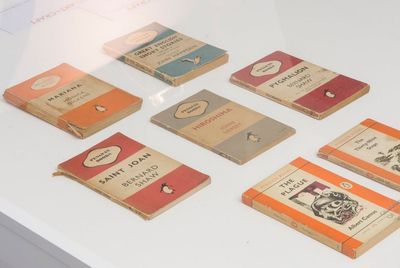

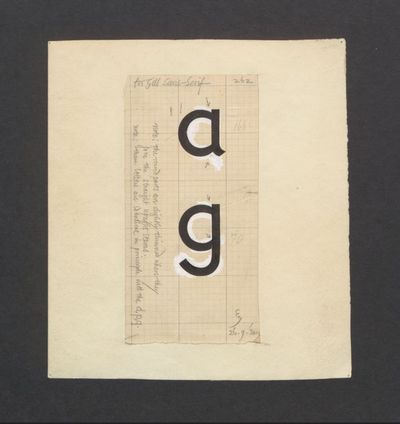

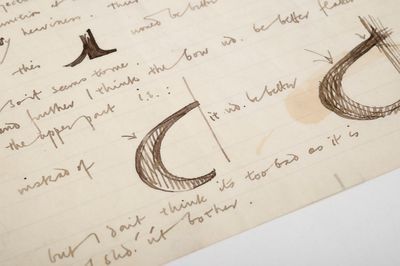

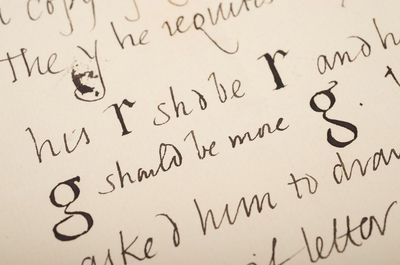

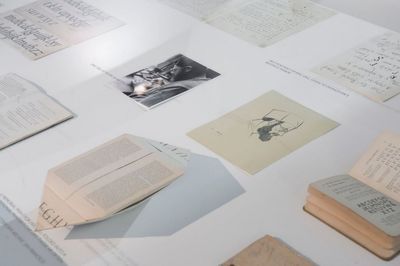

What connects the hit Pixar film Toy Story, a Penguin paperback of Camus���s The Outsider and London Underground? The answer is the typeface Gill Sans, which was designed by Eric Gill (1882���1940), one of the most idiosyncratic artists and typesetters of the twentieth century. Known not only for his artistic seriousness but also for some of the more depraved aspects of his private life, he is the subject of an exhibition mounted at the Old Truman Brewery in Shoreditch. The exhibition has been organized by the Monotype corporation in partnership with Eye magazine, the Five Points Brewing Company, FIELD, Ditchling Museum of Art and Craft and the Letterform Archive; and showcases two of Gill's best-known fonts, Gill Sans and Joanna.

While typefaces may seem a slightly nerdy or trivial interest, they were, for Gill and others, a key cultural and ideological battleground in the modernist disturbances of the early twentieth century. Ditching the ornate lettering of the nineteenth century was an attempt to throw off wallowing bourgeois sentiment. Bold, clear type ��� and in particular the sans-serif typeface, whose pioneers included not only Gill but also the designers of De Stijl, Bauhaus and Soviet Constructivism ��� made literature, and information, accessible to all.

The Monotype newspaper that accompanies the exhibition contains an interview with Terrance Weinzierl (the designer of a new font, Joanna Sans Nova) in which we are reminded that Gill was very keen for Gill Sans to be ���used or reproduced by ���average��� people���. It's interesting, and a little disconcerting, to reflect on the legacy of such aesthetic innovations in the fashionista pop-ups and hipster coffee shops clustered around the brewery, which may or may not have met the serious moral purpose and ideals of Gill���s project.

Functionality was important to Gill, and the exhibition shows us the diverse uses to which Gill Sans was put. The upper-case Gill Sans Bold gave a special crispness and directness to the iconic Penguin and Pelican paperback editions of the 1940s and 50s: the clarity of the font seems almost to demystify literary works that had previously been published in rather stuffy, hard-backed and curlicued volumes.

The use of Gill Sans by British Rail ��� notably on a poster advertising holiday breaks on the Continent, which were becoming accessible to more people than ever ��� seems to usher in boldly a new world of cosmopolitan excitement. And its use by London and North Eastern Railway across its timetables, carriages and signage was one of the first assertions of a clear corporate identity through design.

But there was more to Gill Sans than modernist functionality. Gill���s fascination with the Arts and Crafts movement and the ideas of William Morris also finds expression in the design idiosyncrasies of his most famous typeface. The exhibition presents a number of Gill���s original design drawings on squared paper, which show that Gill Sans combines an orderly regularity with a certain capriciousness. When you look closely, you start to notice the undulating "shoulder" (as typographers call it) of the Gill Sans "m"; or the "oblique terminus" on Gill���s lower-case letters "e" and "s" (the off-vertical slant that finishes the downward stroke of the letter) ��� both give the impression of a draughtsman and not a machine at work in the conception and shaping of individual letters. That impression perhaps helped to offset the concern some early modernist typographers had that sans-serif type might lend itself to authoritarian messages (Gill himself was socialist and pacifist).

Gill, like other modernist typographers, disliked the ornate fonts of the nineteenth century, not just because they obscured the reader���s access to words but also because of their dishonesty: they concealed the industrial mode of production. Such views are expressed in all the nuances of Gill���s typographical innovations, which are paid glorious attention in this exhibition. It offers a useful reminder of the ways in which aesthetic and design questions are fundamentally embedded in even our most ordinary of reading experiences.

The exhibition runs until Tuesday November 10.

Eric Gill in the TLS:

"Prophet as predator": a review by Malcolm Bull of Eric Gill by Fiona MacCarthy (February 17, 1989)

November 7, 2015

At second hand

There's a minor coup on the back page of this week's TLS, for those of the book-collecting frame of mind. There our diarist J. C. reports on finding a dust-jacketed volume of Henry Miller's Plexus, the first publication of the celebrated Olympia Press in Paris, in Notting Hill's Book & Comic Exchange. This is not one of the 2,000 copies advertised for sale but a printer's copy, with his inscription and initials adorning the front free endpaper.

That's not bad going, I'd say, for ��5 in Book & Comic Exchange. Book collectors tend to save what excitement they can muster for association copies ��� principally books inscribed by their authors for other notable figures. Besides their (sometimes fairly arbitrary) market value, we are told, such inscriptions often have their own unique stories to tell. Do humbler, unassociated copies tell their own stories?

Such bibliographical tales take diverse forms, as is often revealed in the pages of the Book Collector or Henry Woudhuysen's TLS reports from the auction rooms. A copy of Eyeless in Gaza, as Professor Woudhuysen reported earlier this year, emerges from one sale catalogue as the object of a good roughing-up at the hands of the biographer Christopher Sykes, then Jean and Cyril Connolly: Jean has embellished it with a drawing of somebody being sick at the front; another sketch has God looking down despairingly on Huxley at work and exclaiming "O Dear! O Dear! O Dear!"

For a time, that copy belonged to one of the TLS's most distinguished bibliophile contributors, Anthony Hobson. What about more ordinary types and their more ordinary books? Well, J. C.'s Perambulatory Books series reveals one or two more he's picked up over years. Or there's the the writer and performer Nathan Penlington, who describes in The Boy in the Book how he bought 106 "Choose Your Own Adventure" novels on eBay and ended up tracking down their previous owner (out of whose teenage diary a tantalizing page had come with the set).

The journalist Josh Spero more recently carried out his own investigation into the subject. Spero's Second-hand Stories isn't so much about the books themselves as the lives of their previous owners ��� people who happened to apply to the same school (University College School in Hampstead) as Spero, or the same Oxford college (Magdalen). As a classicist by education, Spero intersperses episodes of autobiography with brief accounts of the previous owners of his classics books. The actor Sebastian Armesto turns out to be the former owner of North & Hillard's Latin Prose Composition, rather than his father, the historian and TLS contributor Felipe Fern��ndez-Armesto. The poet Peter Levi (one of the "great barely remembered literary figures of the last century", we're told) unwittingly bestowed on Spero a copy of Maurice Bowra's Odes of Pindar, which certainly qualifies as an association copy: it's inscribed "with love and gratitude" from the translator to the poet, who had helped him out with "many wise suggestions".

There's some enjoyable detective work in Spero's pages, although I take the point that some book owners' profiles are flatter than others ��� men are born equal, we're told (an interestingly tenacious untruth), but apparently they do not go on to live equally interesting lives. And not all books are so keen to reveal their owners' secrets, anyway.

Another small mystery, from Second-hand Stories: a copy of Corrado Ricci's Via Dell'Impero, co-written with Antonio Colini and Valerio Mariani, passes through the hands of Belinda Dennis, another classicist and a former president of the Association for Latin Teaching. The title itself is a clue to the book's age, as are the last letters on the title page, "A. XI E. F.", which constitute a particularly sinister way of describing the year 1933: Anno XI nell Et�� Fascista; the "eleventh year of the Fascist era", as Spero points out, "which began in 1922, when Mussolini became prime minister". The name of the road was later changed; what Spero cannot tell us is what Belinda Dennis (who died in 2003) made of it all.

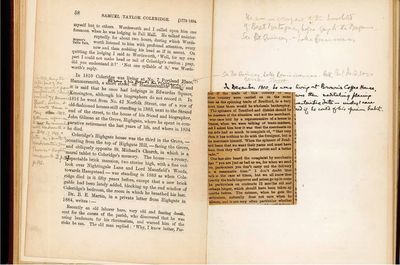

Facing pages from my own current case of curious provenance are reproduced above. They come from a book I bought a while ago, for a whole pound less than J. C.'s Plexus volume: Literary Landmarks of London by Laurence Hutton.

Hutton was an American critic and collector (of death masks, among other things). Edinburgh, Florence, Jerusalem and Oxford were among the other cities covered in his "Literary Landmarks" series. Nothing if not of his age, Hutton notes that the authors of Jane Eyre and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall "came to London in 1848, without male escort", and stopped at the Chapter Coffee House, No 50 Paternoster Row. Charles Dickens's last London home, 5 Hyde Park Place, long-since rebuilt, can be described here as "unaltered".

This particular copy shows that Hutton's series enjoyed some success: it's from the "revised and enlarged" fifth edition of 1889. For some time, it appears to have languished at W. H. Smiths on the Strand, until a George Laish bought it, on August 23, 1935, and took the trouble to note the date inside.

It wasn't the first or the last "mark of ownership" these Literary Landmarks were to receive, as you can see ��� the volume has been irregularly updated with newspaper cuttings and notes in pen and pencil, continuing that process of revision Hutton himself carried on from one edition to the next. The most yellowed cutting dates from 1896 ("here we have to lament the loss of Leigh Hunt's house, 8, York-buildings"); others date from the 1980s. At least two snappers-up of unconsidered trifles contribute notes in distinctively different hands, perhaps out of a shared enthusiasm for this hobbyist's game, sustained over the best part of a century.

I don't think I'll be playing the game myself ��� Literary Landmarks only comes to mind now because I'm reviewing a couple of modern guides to literary Britain that, up to a point, follow Hutton's formula. The major difference being that these new books, by Nick Channer and Frank Barrett, do not take for granted that the reader knows much, or even anything at all, about the writers and the literary landmarks they visit. Introductory, sub-Wikipedia information bulks out both books, whereas Hutton is explicit about his not writing for those "who need to be told who Pepys and Johnson and Thackeray were, and what they have done".

Both Channer and Barrett will need updating one way or another; I should think there are already one or two review copies with instructive scribbles in the margin to set the game going again.

November 5, 2015

A good death?

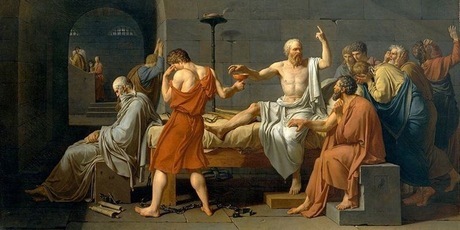

"The Death of Socrates" by Jacques Louis David, 1787

By WILLIAM REES

Perhaps it is fitting that the most interesting moment of A Good Death?, a symposium about death and dying which took place at Senate House last Wednesday, came towards the evening���s end. Professor Andrew Cooper of Tavistock and Portman NHS Trust, the fourth speaker to address an audience of about fifty, explained that while a few of us would die suddenly and unexpectedly, and a few peacefully, the majority of us would die slowly and incrementally, either of, or with, dementia. A gasp silently passed through the room.

Not that Professor Cooper paused to sigh or to laugh at our predictable response ��� already he was off, talking in his erudite, humane and generous way about the precarious communicative channels between the living and the dying.

The interdisciplinary event comprised four speakers: two experts on the ancient world and two on modern practice. Professor Eleanor Robson (of University College London) spoke about ancient Mesopotamia ��� in particular about the Epic of Gilgamesh, and the eponymous king���s struggles to understand mortality. Professor Robson had some interesting comments to make about the ���medicalization��� of death, a term that became a leitmotif for the evening, fluttering back and forth between the speakers.

Jumping forward a millennium-and-a-half, Professor Michael Trapp (of King's College London) spoke about Epicurus and Socrates, the two classical thinkers who have left the biggest imprints on philosophical ideas about death. For Socrates, philosophy itself is a preparation for death, and to die well is to die as oneself. For Epicurus, of course, all of that could be disposed with: one should not think too much about death: for as long as I am, death is not; and when death is, I am not.

On the face of it, these two positions are poles apart; are they not united, though, by their attempts to domesticate death ��� to control it, respectively, by staring it down or by turning away? It has never been clear to me that either has much relevance to the modern experience of dying, which is often very protracted, hardly ignorable and usually leaves us dispossessed of control long before the final dispossession.

But is the ���good��� death not anyway a rather suspect concept? This question, implicit in the title's punctuation, was taken up by Dr Mary Bradbury (of the British Psychoanalytical Society), who asked a startlingly simple question: for whom is the good death good? Dr Bradbury argued that the professionalization of death ��� what we might call the ���death industry��� ��� is an ambivalent development, both for the dying and for those they leave behind. In a crowded social context, with so many competing claims to what constitutes a good death (medical, (inter)personal, religious), would it not be wiser to search instead for a ���good enough death���?

Dr Bradbury left this question tantalizingly open; but it was taken up by the final speaker, Professor Cooper. The good death, he argued, is a distraction from the messier, more pressing issue of the oft knotty communication between those who are dying and those who are not yet. Impassioned but never moralizing, Cooper spoke about how our failure to rise to the challenge, to imagine more productive forms of communication that could take place between the living and the dying, led to those who are dying facing a ���social death���, which sometimes comes long before that other one.

The question-and-answer session that followed was, as is often the case, too short. After all, this is the one topic in which every person has a stake ��� a point cast poignantly into relief when a young boy, probably no more than twelve years-old, stood up and asked an eloquent and affirming question (about whether our obsession with what comes after death distracts us from life). As the evening came to a close, the accumulation of voices and perspectives pointed to how, far from being in conflict with or displaced by science, philosophy remains as important as ever. Advances in medicine have prolonged our lives ��� and our deaths. In doing so science has raised questions that it alone cannot answer; it has, in other words, breathed new life into philosophy���s ebbing relationship with death: a challenge to which philosophy must rise.

November 3, 2015

Translation and the case for pragmatism

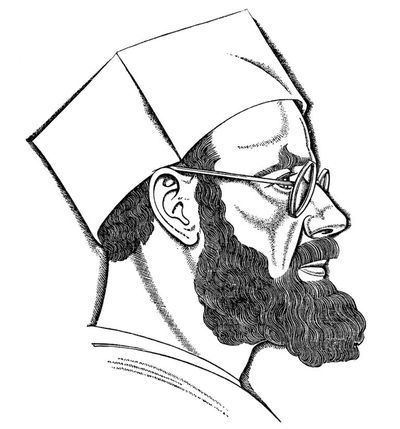

Samuel Solomonovitch Koteliansky by Mark Gertler, 1930

By BRYAN KARETNYK

The lecture theatre at UCL���s Institute of Archaeology proved an unexpectedly germane setting for Thursday evening���s talk on "Alexander Pushkin and the myth of untranslatability". Lining the walls of the Leventis Gallery are softly lit display cabinets ��� home to the institute���s collection of Cypriot and Eastern Mediterranean ceramics ��� with placards, bidding the viewer to reflect on antiquity���s "cross-cultural channels of communication". It is precisely this link, between history and communication, that UCL���s Translation in History lecture series, now in its fourth year, endeavours to explore.

An engaged audience comprising the general public, academics and even a number of veteran translators convened to hear Robert Chandler discuss the trajectory of literary translation from Russian into English over the past hundred or so years. Chandler, who is most noted for his translations of Vasily Grossman, Andrei Platonov and, more recently, the ��migr��e writer Teffi, is exceptional on the list of speakers in the UCL lecture series: he is the only full-time practising translator, and indeed the only non-academic. Perhaps it was for this reason that his approach to the task seemed so refreshingly pragmatic.

Following words of welcome from Anna Ponomareva, one of the series���s organizers, Chandler noted archly that his talk would take in a broad swathe of translators and their offerings: ���Some I admire . . . Some I don���t���. The candidates for scrutiny in the first half of the lecture were Constance Garnett, who in Chandler���s view ���really created Russian literature in English���, and the Russian-born translator Samuel Koteliansky. In an attempt to rehabilitate Garnett after Vladimir Nabokov and Joseph Brodsky���s ���sneering��� derisions (the mistranslations, the omissions, the notorious accusations that English readers could not tell Tolstoy and Dostoevsky apart because they were reading pure Garnett), Chandler mounted a defence of her work, noting in particular Katherine Mansfield and Virginia Woolf���s indebtedness to Garnett���s translations of Chekhov. Moreover, he mused, Garnett was modest and aware of her own limitations as a translator.

These two vanguard figures also provided a poignant point of departure to consider what Chandler described as the modern-day dislocation and "ghettoization" of translators apart from the mainstay of literary culture. Chandler noted in particular how a collaboration between Koteliansky (���Kot��� to his close acquaintances), D. H. Lawrence and Leonard Woolf had resulted in, to Chandler���s mind, one of the finest translations of Ivan Bunin���s short story "The Gentleman from San Francisco". Even Koteliansky���s ���remarkable . . . bold��� foreignisms are deserving of praise, he said. Citing the line ���strings of bare-shouldered ladies rustling with their silks on the staircases and reflecting themselves in the mirrors���, Chandler extolled the efficacy of Koteliansky���s Russianizing ���with their silks��� (shelkami, the instrumental) and the even purposely defamiliarizing ���reflecting themselves��� (otrazhaiushchikhsia, an ordinary reflexive participle). Note, however, that Bunin himself could have achieved Koteliansky���s effect, had he opted for the active otrazhaiushchikh sebia. Undoubtedly a case where the translation is more striking than the original.

The second half of the talk examined a case study of Pushkin���s Eugene Onegin, which Chandler termed "exceptional" in that it represents one of the few instances where successive translators have almost uniformly improved on their forerunners ��� from Charles Johnston���s first ���readable��� Onegin to Stanley Mitchell���s pinnacle of ingenuity and aesthetic sophistication. The crux of Chandler���s argument against translations such as Nabokov���s is that the adoption of any ���rigid ideology��� (in this instance Nabokov as an ���Apostle of Literalism���) ultimately impoverishes a translation, focusing as it does on only one facet. It simplifies the translator���s task by eliminating the need to balance a work���s formal aspects with its content. Quoting from Clive Wilmer���s TLS article "Dante made plain" (1996), Chandler spoke of the ���sacrifice��� and ���painful choices��� a translator must make, concluding that only in treading the path of pragmatism may one, as Wilmer puts it, hope for ���the resurrection of the poem in its new form���.

Chandler���s case for pragmatism is a convincing one. Although I did pause for a moment when he praised the flourishes in Koteliansky et al���s Bunin. The effects are indeed arresting, but they do raise the question: given the chance, should a translator ever presume to ���enhance��� a text? There are, of course, no easy answers. All authors have good and bad days, but surely the translator betrays a moment of self-doubt in not letting the works ���reflect themselves���?

The next lecture in the series, "Roman Jakobson and the translation of poetic language" , will be delivered by Professor Jean Boase-Beier (UEA) at 6.30pm on Thursday, November 26.

Robert Chandler in the TLS:

"A hoarded treasure", August 19, 2015

"In Baba Yaga's hut", May 15, 2013

Robert Chandler writes about the Soviet elite at Yevgenia Solomonovna Yezhova's salon, September 10, 2010

November 2, 2015

Finding the plot around Copley Square

Margaret Atwood and Kelly Link; �� Mike Ritter/Ritterbin Photography

By MAREN MEINHARDT

The Boston Book Festival is now in its seventh year. From its inception, it has attracted enticing and high-profile writers ��� Orhan Pamuk delivered the keynote address at the inaugural event in 2009; since then, speakers have included Bill Bryson, Amartya Sen, Joyce Carol Oates, Siddhartha Mukherjee and Salman Rushdie.

This year���s event ��� a concentrated, high-energy affair taking place around Copley Square in the Back Bay area ��� was opened by Margaret Atwood. The talk had been sold out for months ��� the woman standing next to me and scanning the pews in the Old South Church sanctuary for a place to squeeze in confided that she had bought her ticket back in July.

Witty, elegant and infinitely gracious, Margaret Atwood generated instant adoration. Her conversation partner, Kelly Link (author of, most recently, a short-story collection called Get in Trouble) was clearly overawed, too, suggesting, at one point, that Atwood must be some kind of a deity, and thus immortal. ���Well, I���ve got news for you!���, Atwood cackled.

Atwood talked a bit about her childhood reading ��� beginning with comics that were considered harmful and had to be read secretly, under a flashlight. Her school reading, by contrast, seemed pleasingly untouched by such concerns. A book called Donovan���s Brain stood out in particular. It featured a brain floating around in a solution and being fed ���brain nutrients��� to keep it alive, until, unfortunately, it was ready to take over the world. Atwood declared that it had opened her eyes to the powers of literature: it turned out that the world was saved, and the brain successfully killed off, through the strategic deployment of some lines of poetry by Verlaine.

Medical themes had dominated Atwood���s life from early on, she explained. Her grandfather had been a doctor in Nova Scotia ��� somebody who made home visits on horse-drawn sleighs, and delivered babies on kitchen tables. The take-home message for Atwood���s mother was best summarized as ���don���t get sick���.

As to her own appetite for inflicting death and destruction in her dystopian MaddAddam trilogy (Oryx and Crake, The Year of the Flood and MaddAddam), Atwood shrugged off such suggestions elegantly. After all, she protested, ���I didn���t polish off anything except for the human race���. And anyway, the demise of mankind would probably be quite good for other life forms.

Atwood finished with a mini masterclass on how to best murder somebody on a ship. While I can���t give away too many details, the plan hinged on the fact that, when she first contemplated the problem, a high number of her fellow passengers happened to be called ���Bob���.

���How do you justify romantic love in a patriarchal society?���, one member of the audience asked her afterwards. ���I don���t know, it just happens���, Atwood replied, smiling, and then took a closer look at the questioner: ���how old are you?��� On learning she was twenty-two, Atwood said, encouragingly: ���you���re going to have fun. At twenty-two, you don���t know the plot. I know the plot of my life ��� most of it���s already happened. And I know how it���s going to end���.

How it is going to end is the question that occupied Atul Gawande in his keynote talk. A doctor at Massachusetts General Hospital and the author of the acclaimed Being Mortal, he talked about what happens when doctors, equipped with all possible medical competence, are faced with patients who won't get better. Our assumption that our most prized goals are health and independence is not happily reconciled with the fact that we live in a world where people (if they are lucky!, Gawande pointed out) will eventually get old and frail.

Three-quarters of patients, Gawande told us, accept care they do not want, because their families want them to. This had been what had happened in his own family, during his father���s last illness, and it had been an abiding source of regret.

What is important, he said, is to be clear what it is that we we want doctors to fight for. And this does not in every case equate with survival.

Gawande quoted a study which showed that people tend to be happier in their seventies than they were in their forties. Happiness is not necessarily compromised by physical limitations, but it is once a person stops being in charge. This is what happens fairly reliably when people become institutionalized. But, Gawande urged, when you���re in a wheelchair, you can be in charge; if you���ve got dementia, you can still be in charge. Wellbeing, he concluded, is something that is bigger than health and survival.

Atul Gawande interviewed by Meghna Chakrabarti; �� Mike Ritter/Ritterbin Photography

October 31, 2015

Small publishers, smaller books

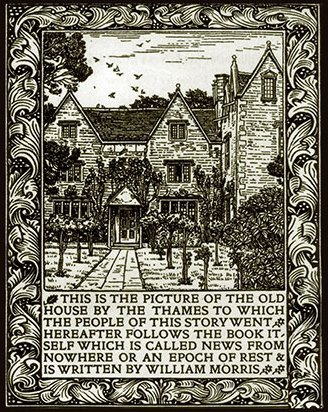

Kelmscott Manor, Gloucestershire, by William Morris; frontispiece to News from Nowhere, c.1892

By MICHAEL CAINES

Take a piece of A4 paper. Fold it in half (reducing it to A5 size), then twice more (A6; A7). A little more unfolding and refolding, interrupted by one snip of the scissors, and there you have it ��� a booklet of eight pages. Stitch it and trim the edges. Now all you have to do is cover it with suitable words and pictures . . . .

As threatened previously on this blog, next week's issue of the TLS will carry reviews of Unshelfmarked, Michael Hampton's Dewey-defying compendium of artists' books, and Suite V��nitienne, Sophie Calle's subversive (and recently reissued) exercise in artistic stalking. As both publications demonstrate, the art of the book can be an elaborate one ��� Hampton gives examples of "ornate incipit capitals" and vellum pages, as well as virtual books dependent on an entirely different but comparably sophisticated craftsmanship. No doubt the evidence of the non-virtual kind of craftsmanship will be abundantly on display during this weekend's Oxford Fine Press Book Fair.

To those examples, you could add disparate examples such as Le Songe du Vergier, the wonders of the R. E. Hart Collection in Blackburn, Vince Koloski's "The Cabinet of J. Alfred Prufrock" and the productions of WIlliam Morris's Kelmscott Press (the antithesis of what he feared books were becoming, as uncovered by Jan Marsh in this week's TLS). With all due respect to the realms of gold: realms of paper will do just as well for me.

Yet Unshelfmarked also includes some seemingly more modest examples of book art: the "spuriosity" of a fake hornbook; St��phane Le Mercier's Lectures pour tous, a poster cataloguing the artist's purchases from a Marseilles bouquiniste. I suppose I'm one of those people who take everyday bits of paper like posters and postcards for granted, as I can still be naively surprised by the clever effects artists can achieve with them. Artists such as Caroline Isgar, for example, who created, with Mich��le Roberts, this Dark and Marvellous Room in the style of a souvenir strip of postcards:

Travelman Short Stories and the A3 Review, meanwhile, show what can be done with a single-sheet concertina:

And simpler still is the one-sheet book of the school-holidays kind described above, which is just over a minute's work for practised hands. Last year's Small Publishers Fair introduced me to this finely crafted example designed by Mette Ambeck and adorned with a few well-chosen words by Nancy Campbell:

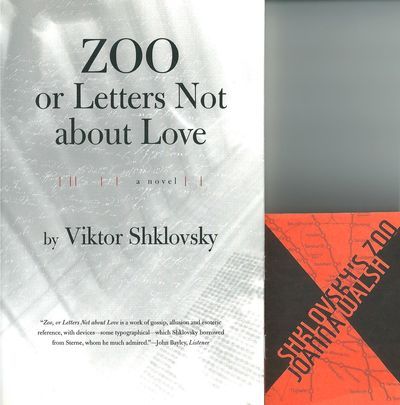

See also Hazard Press's "micro-books": Finding Your Way to Dylan Thomas, Signs of Oliver Twist in Newport et al. And here's one last example of this trend in miniature book-making, placed next to its more conventional counterpart for scale's sake (please excuse my god-awful attempt at scanning):

The TLS reviewed Viktor Shklovsky's epistolary novel Zoo; or, Letters Not About Love in 1931, forty years before the appearance of Richard Sheldon's English translation, and called it "excessively personal and entirely delightful". The epistolary form Shklovsky adopted led a later reviewer to describe this "arch-modernist" as being, paradoxically, "spiritually a man of the eighteenth century; not so much an imitator of Sterne, Fielding, Voltaire, as their contemporary".

Both Oulipo-philes and Shandy-ites will feel at home here. These letters are not about love for their recipient, who forbids him to write of the subject, but cover everything else under the sun ��� animals in the Berlin Zoo, Tahiti, Russian poets ��� while stowing away their author's reflections on the forbidden subject. So I read the A7-sized Shklovsky's Zoo by Joanna Walsh (published earlier this year by Tony White's deliberately lo-fi and generous-spirited Piece of Paper Press) as a complimentary complement: it's not about reading the book itself but trying to get hold of a copy, as well as a writing residency, Kafka, the narrator coming adrift (a relationship has ended, and the fellow writing residents aren't exactly her cup of tea). Or it's about those things and it's not . . .

A fictional version of Joanna Walsh circles a fictional version of Viktor Shklovsky circles a fictional version of the writer Elsa Triolet (a "Third H��lo��se", who escaped and later became the first woman to win the Prix Goncourt). That seems like plenty to find tucked away in a few pages made from a single sheet of paper.

October 30, 2015

Nawal El Saadawi at point zero

Nawal El Saadawi, 2011; Photograph by Richard Pohle/The Times

By ALEXANDER STARRITT

Underground in a bar with exposed brickwork, shiny tiling and hundreds of bare light bulbs massed together on the ceiling, in London's no longer all that trendy area of Shoreditch, a sell-out crowd of a hundred young women has come to listen to the eighty-four-year-old Egyptian psychiatrist Dr Nawal El Saadawi.

The MC describes El Saadawi as one of the foremost feminist thinkers in the Middle East. A prolific author, she has written novels such as Woman at Point Zero (1975), which tells the true story of Firdaus, a prostitute sentenced to death for killing a pimp. For such feminist writings and activism, El Saadawi lost her job; she was imprisoned and forced into exile in America, where she taught ���creativity and dissidence��� at Duke University in North Carolina, then at Harvard, Yale, Columbia and the Sorbonne.

The event has been organized at The Book Club by For Books' Sake, an organization that champions women writers. There is a warm-up act: Cecilia Knapp, who has performed a one-woman show at the Camden Roundhouse about "being a girl". She makes self-deprecating remarks and reads poems from an exercise book about her lovability or unlovability, one about her father and one that is a commission ���about gentrification in certain parts of London���.

Everything shifts when El Saadawi arrives, halfway through one of the poems. She sits on a chair by the door, small, fidgeting, curious, looking around, inspecting Knapp���s shoes, squinting into the crowd. People keep creeping across to greet her. I wonder what Knapp's description of working in a pub in Mile End means to her. Knapp finishes her set; El Saadawi vehemently applauds and then, jumping ahead of the scheduled but already forgotten second act, takes the stage. There's whooping and cheering from the crowd, at which El Saadawi grins in surprise and pleasure.

When she starts speaking she is direct, generous, serious. She is talking about courage (the MC wants to know where you get it from), about imprisonment and exile. Her lexicon doesn���t fit with this room or this time: revolution, dissidence, ���the system���. She is asked "when you look back on your work, what do you think about it?", and replies that when she went to America, students in her classes had read Woman at Point Zero and would come up to her to say that they felt they were Firdaus. This, she says, is ���better than the Nobel Prize���.

Firdaus, in Nawal���s telling, was clandestinely offered a pardon if she would show remorse for killing the pimp, but said, ���I am ready to die, but not to regret���. She was ���the most honourable woman I have ever met���. She struggled to be free from oppression by those around her and all her life she was betrayed ��� by her family, by the law ��� and in the end she was executed.

Nawal wins the audience by telling them these things in the same voice in which she says she doesn���t like teachers or doctors or writers (she herself being all three), or that, during the protests in Tahrir Square, ���I was so happy I went back to my childhood. I thought I was a child. I was eighty at that time, but I felt eight���. In fact, there���s something admirably childlike about the brightness of her enthusiasm, her haste, her peremptoriness. She only loses the crowd when she gets on to the Taliban and al-Qaeda, with whom she considers the neo-colonial powers to be collaborating to divide and rule the Arab world.

But then there are questions. Nawal makes the young women asking them come up and sit next to her. All introduce themselves to her in Arabic, then speak English to the crowd. All except the last one, whose English isn't good enough and who brings a friend up to translate. She has asymmetrical hair, white high-top trainers, jeans rolled up above the ankle. She starts talking and Nawal gleefully interrupts; she cannot wait for the translator: ���She says, I feel like Firdaus���.

Shy but defiant, the young woman continues, and there���s cheering from the part of the crowd that already understands. Her friend interprets: ���I had to wear a scarf for twelve, thirteen years. But then I took it off���.

Nawal El Saadawi in the TLS:

"The squirrel and the hawk", August 17, 2001

"Beyond the veil", January 10, 1997

October 28, 2015

Sir John Soane���s danse macabre

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

Sir John Soane ��� like his house (now a museum in Lincoln���s Inn Fields), his architecture and his writing ��� is peculiar and perplexing. Without him the Dulwich Picture Gallery wouldn���t look like it does, nor phoneboxes: the family tomb Soane designed and built for his wife Eliza, after her death in 1815, in St Pancras Old Churchyard (one of only two Grade I listed monuments still standing in London; the other is Karl Marx���s tomb in Highgate Cemetery) apparently inspired Sir Giles Gilbert Scott���s design of the British red telephone box.

A fanciful, colour-washed painting (above) of this monument (alongside original drawings created by Soane���s architectural office) is on display in a new exhibition, Death and Memory: Soane and the architecture of legacy, at the Soane Museum. Obsessed with funerary architecture, Soane didn���t simply make the tomb a memorial to his wife; it also commemorates his favourite architectural motifs. Here we have a square-based shallow dome, incised pilasters, an abundance of ancient death symbolism.

Other architectural drawings, selected by the curators from the 30,000 in the museum���s archive, show circular mausoleums, obelisks honouring Battles at Trafalgar, Waterloo and Blenheim, and a plan of an unexecuted monument to George Washington ��� this hangs below a beautiful, minimalist interpretation of the plan from the 1970s���80s (circles within squares, and a delicate row of twig-trees in the corner, like a Sol LeWitt illustration), neatly suggesting that Soane���s funereal influence continues. And, thankfully, disproving that architectural drawings and models are dull or nonsensical to an amateur. (If you���ve been to the Royal Academy���s Summer Exhibition over the past few years, you may have noticed a change in the architecture room: almost-impenetrable computer graphics are now overshadowed by dynamic designs that are painted, photographed or inked; there���s even an award for the best model, partly based on architecture, partly on the execution of the model itself.)

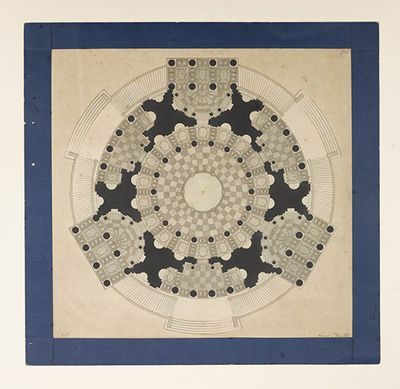

Plan of a mausoleum by William Chambers from the Soane collection

Plan of a mausoleum by William Chambers from the Soane collection

For me, one item in Death and Legacy is particularly fascinating: a cork model of an Etruscan tomb collected by Soane ��� the roof gapes open to reveal a comical skeleton lying on a plinth, huge ceramic vases, and stucco pigs and dogs on the walls, all of which are slightly off-scale and archaeologically inaccurate. This is much like the inside of the Soane museum itself, with its sombre catacomb-like basement, relics, altarpieces and Egyptian-mummy cases placed in every crevice.

Henry James picked up on this motley, unique collection in his short story ���A London Life��� (1888):

���The heterogeneous objects collected by the late Sir John Soane are arranged in a fine old dwelling-house, and the place gives one the impression of a sort of Saturday afternoon of one���s youth ��� a long rummaging visit, under indulgent care, to some eccentric and rather alarming old travelled person.���

Preliminary design for the Soane Museum, by James Adams, 1808

Preliminary design for the Soane Museum, by James Adams, 1808

Soane was so preoccupied with ruins, remains and shaping memory through architecture that, as well as making his house an ���academy��� of design and a personal legacy, he left behind sealed receptacles (a sort of time capsule) a few months before his death with instructions for them to be opened on the fiftieth, seventieth and eightieth anniversaries of his wife���s death ��� as though their contents had some cosmic significance. Instead, we find a pair of his masonic gloves; false teeth; a small, round piece of glass from Sudeley Castle; correspondence relating to his wayward son George (who refused to become an architect, constantly badgered his parents for money ��� he was a novelist ��� and wrote critical reviews of his father���s buildings, which Soane ��� disappointed, saddened ��� framed and displayed in the house, labelling them as his wife's ���Death Blows���); and a bizarre manuscript, Crude Hints Towards an History of My House in Lincoln���s Inn Fields, now republished by the museum to accompany the current exhibition. In the guise of an antiquary, Soane here imagines his house as a ruin in the future being inspected by visitors who speculate about its origins and function. Was it a Roman temple, a burial site, a monastery, a magician���s lair? The manuscript is written in a single column down the right-hand side of the page, leaving plenty of space for marginal notes ��� of which there are many, mostly challenging the haughty voice in the main text (���is it possible Architecture might have been better understood . . . in Italy than in Britain ��� in the succeeding times the Britons were designated ���barbaros Brittannos������). On seeing a fragmentary inscription ���et filii filiorum���:

���What an admirable lesson is this work to shew the vanity of all human expectations ��� the man who founded this place piously imagined that from the fruits of his honest industry & the rewards of his persistence [and] application he had laid the foundation of a family of Artists and that the filii filiorum of his loins might, smitten with the love of Art and anxious to shew their gratitude for the benefits & care & comfort they derived from it, dwell in this place from generation to generation ��� Alas poor man he flattered himself that a race of Artists would have been raised up whose efforts from the advantages they set out in life with . . . would have raised Architecture to its meridian splendour ��� Oh man, man, how short is thy foresight.���

Although, there are, of course, three alternative endings. The third one is the most whimsical, dark and, incidentally, my favourite, its final line being: ���Oh what a falling off do these ruins present ��� the subject becomes too gloomy to be pursued ��� the pen drops from my almost palsied hand . . . ���. Fingers fall away from keyboard doesn���t quite have the same effect.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers