Small publishers, smaller books

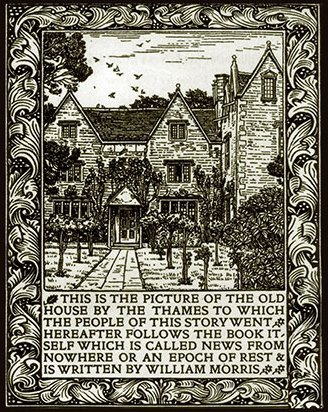

Kelmscott Manor, Gloucestershire, by William Morris; frontispiece to News from Nowhere, c.1892

By MICHAEL CAINES

Take a piece of A4 paper. Fold it in half (reducing it to A5 size), then twice more (A6; A7). A little more unfolding and refolding, interrupted by one snip of the scissors, and there you have it ��� a booklet of eight pages. Stitch it and trim the edges. Now all you have to do is cover it with suitable words and pictures . . . .

As threatened previously on this blog, next week's issue of the TLS will carry reviews of Unshelfmarked, Michael Hampton's Dewey-defying compendium of artists' books, and Suite V��nitienne, Sophie Calle's subversive (and recently reissued) exercise in artistic stalking. As both publications demonstrate, the art of the book can be an elaborate one ��� Hampton gives examples of "ornate incipit capitals" and vellum pages, as well as virtual books dependent on an entirely different but comparably sophisticated craftsmanship. No doubt the evidence of the non-virtual kind of craftsmanship will be abundantly on display during this weekend's Oxford Fine Press Book Fair.

To those examples, you could add disparate examples such as Le Songe du Vergier, the wonders of the R. E. Hart Collection in Blackburn, Vince Koloski's "The Cabinet of J. Alfred Prufrock" and the productions of WIlliam Morris's Kelmscott Press (the antithesis of what he feared books were becoming, as uncovered by Jan Marsh in this week's TLS). With all due respect to the realms of gold: realms of paper will do just as well for me.

Yet Unshelfmarked also includes some seemingly more modest examples of book art: the "spuriosity" of a fake hornbook; St��phane Le Mercier's Lectures pour tous, a poster cataloguing the artist's purchases from a Marseilles bouquiniste. I suppose I'm one of those people who take everyday bits of paper like posters and postcards for granted, as I can still be naively surprised by the clever effects artists can achieve with them. Artists such as Caroline Isgar, for example, who created, with Mich��le Roberts, this Dark and Marvellous Room in the style of a souvenir strip of postcards:

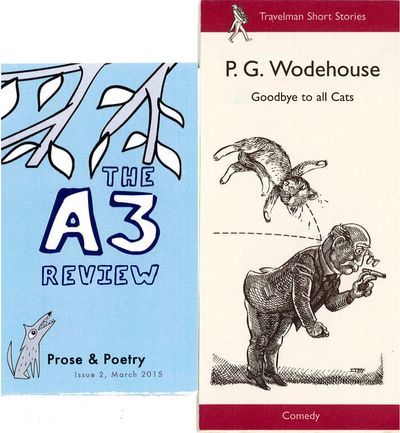

Travelman Short Stories and the A3 Review, meanwhile, show what can be done with a single-sheet concertina:

And simpler still is the one-sheet book of the school-holidays kind described above, which is just over a minute's work for practised hands. Last year's Small Publishers Fair introduced me to this finely crafted example designed by Mette Ambeck and adorned with a few well-chosen words by Nancy Campbell:

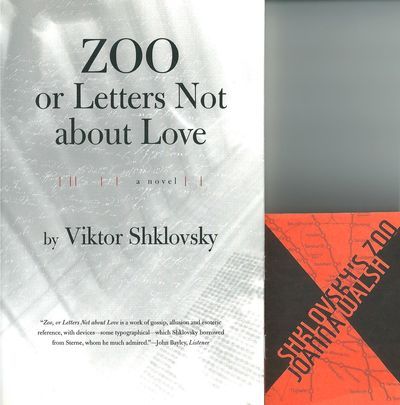

See also Hazard Press's "micro-books": Finding Your Way to Dylan Thomas, Signs of Oliver Twist in Newport et al. And here's one last example of this trend in miniature book-making, placed next to its more conventional counterpart for scale's sake (please excuse my god-awful attempt at scanning):

The TLS reviewed Viktor Shklovsky's epistolary novel Zoo; or, Letters Not About Love in 1931, forty years before the appearance of Richard Sheldon's English translation, and called it "excessively personal and entirely delightful". The epistolary form Shklovsky adopted led a later reviewer to describe this "arch-modernist" as being, paradoxically, "spiritually a man of the eighteenth century; not so much an imitator of Sterne, Fielding, Voltaire, as their contemporary".

Both Oulipo-philes and Shandy-ites will feel at home here. These letters are not about love for their recipient, who forbids him to write of the subject, but cover everything else under the sun ��� animals in the Berlin Zoo, Tahiti, Russian poets ��� while stowing away their author's reflections on the forbidden subject. So I read the A7-sized Shklovsky's Zoo by Joanna Walsh (published earlier this year by Tony White's deliberately lo-fi and generous-spirited Piece of Paper Press) as a complimentary complement: it's not about reading the book itself but trying to get hold of a copy, as well as a writing residency, Kafka, the narrator coming adrift (a relationship has ended, and the fellow writing residents aren't exactly her cup of tea). Or it's about those things and it's not . . .

A fictional version of Joanna Walsh circles a fictional version of Viktor Shklovsky circles a fictional version of the writer Elsa Triolet (a "Third H��lo��se", who escaped and later became the first woman to win the Prix Goncourt). That seems like plenty to find tucked away in a few pages made from a single sheet of paper.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers