Peter Stothard's Blog, page 2

September 2, 2016

by-what-does-it-mean-to-research-contemporary-fiction-in-a-university-how-are-academics-working-in-this-space-different-t

by-adrian-tahourdin-looking-for-the-outsider-albert-camus-and-the-life-of-a-literary-classic-chicago-by-alice-kaplan

Remembering J. B. Trend ��� an unlikely Spanish don

By GEORGE BERRIDGE

The internet is a terrible tool for the easily distracted. How can I possibly respond to emails when the "Random Page" button on Wikipedia exists? Then there���s the time lost on sub-articles, essays and dusty corners of the Amazon bookstore. But occasionally, there can be some real reward in pulling on the thread.

Readers of this week���s issue may have noticed the wonderful letter on The Magic Flute in our "From the Archives" section. Sent to the TLS from the Somme in July 1916 by Lieutenant John Brande Trend, it is an archetype of the form: incisive, informative and witty. Printed when contributions to the paper were anonymous, he signs off MONOSTATOS, B.E.F. (British Expeditionary Force). When you read the date, the worry strikes: did he make it through to the day the guns fell silent? Yes, it emerges, and then some. Not only did he survive the war, but he also went on to pursue his love of Hispanic studies, becoming the first professor of Spanish at Cambridge, a position he held until 1953. (He died in 1958.)

A man of such learning and distinction must surely have graced these pages again? Sure enough, a search of our archives shows that he began reviewing for the TLS in 1919, again demonstrating his knowledge of Mozart, in a review of Michele Scherillo���s book on Neapolitan comic opera. As browser tabs pile up, I come across a reference to him in the collected letters of another reviewer who started writing for the TLS in the same year: Thomas Stearns Eliot. In a footnote I discover that the pair became acquainted in the summer of 1922. In the letter it refers to, dated January 18, 1923, T. S. writes to J. B., who was spending a great deal of time on the Continent:

I had been wondering whether I should hear from you, and whether you had returned from Spain (though I had seen one or two things I thought must be by you, in the TLS) and had been for some time on the point of writing to you. Remember that I have been counting on you, if on anyone, to report to me some treasure from Spain which might be exploited for the Criterion.

Trend began writing for Eliot���s literary magazine in 1924.

Back to the archives. In 1928, we find him passing judgement on V. S. Pritchett���s book Marching Spain.

It is interesting to see how Spain grows upon the author, how the mere fact of being for some time in the country gradually impels him towards directness of expression; and when, towards the end of his stay, his imagination is stirred, he can write naturally and convincingly, without the necessity of that ostentatious jewelry of phrase and metaphor which has spoiled some of the best of his earlier pages.

In July 1933, Eliot writes to Philip Radcliffe, a fellow of King���s College, to ask if he would like to compile a quarterly "Music Chronicle" for the Criterion ��� taking the responsibility over from Trend, who was beginning his job at Cambridge. J.B. had put forward Radcliffe���s name (���I warmly endorse his nomination���).

Trend���s position at Cambridge came in no small part thanks to the help of his lifelong friend Edward Dent, the same Mr Dent he refers to in the Somme letter. Dent had been Professor of Music at the university since 1926. In Duet for Two Voices: An informal biography of Edward Dent compiled from his letters to Clive Carey, I learn that it was Dent who convinced J. B. to visit Spain and write about music. The two lived together in London in the early twenties and, when Dent died in 1957, Trend acted as his friend���s executor. Trend���s final piece for the TLS was published in the issue of February 19, 1944. Under the title "The Poet in Power", part of a series of articles on Latin American books, he praises a biography of the poet and intellectual Franz Tamayo: ���No book could do more to show a European what Bolivia really is than this���.

His love of the country had a notable effect on one of his Cambridge students, Margaret Anstee ��� later Dame Margaret Anstee ��� who died last week at the age of ninety. She had travelled the world as a diplomat for the UN, becoming Under-Secretary-General in 1987. In her last years she divided her time between Herefordshire and "the shores of Lake Titicaca���. It was in the latter location that she sat down to write her memoir, Never Learn To Type: A woman at the United Nations. The photograph that accompanies her Guardian obituary shows her presenting a copy of the book to Kofi Annan. Brenda Maddox applauded it in the TLS of May 30, 2003: ���For a woman of rare achievement, the least of her distinctions is remarkable���.

It was not Anstee's only book: in 2013, her biography of her ���beloved professor��� Trend, JB ��� An Unlikely Spanish Don, was published by Sussex Academic Press. As a review in the newsletter of the British Association of Former United Nations Civil Servants points out: ���JB (as he was generally known) had an immense circle of literary and musical friends [including HG Wells, John Maynard Keynes, Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Le Corbusier and Igor Stravinsky], he poured tireless energy into his many projects, influenced many people and yet by the early 21st century, Trend was virtually forgotten, even in his old Cambridge college���. I hope that, in sharing this colourful history, I can help to revive his memory.

September 1, 2016

Literature and lace don't mix

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Literature can clash with commerce in all sorts of ways, or the two can rub along together. No. 102 Boulevard Hausmann in Paris is where Proust lived from 1907 to 1919, i.e. during his most productive years (���Marcel Proust 1871 ��� 1922 habita cet immeuble de 1907 �� 1919���). An unremarkable five- or six-storey building, it now houses the bank CIC, who are, I imagine, happy to have the plaque to give them a bit of literary cachet.

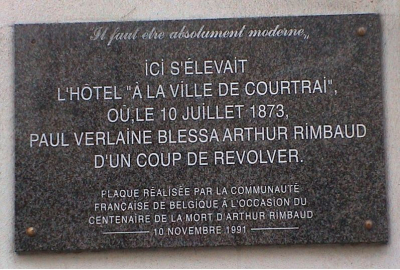

But it���s a slightly different story in Brussels, apparently. In the first of a six-part series on ���Writers in prison��� in Le Monde recently, Marie-B��atrice Baudet revisited the infamous episode when an inebriated Verlaine shot Rimbaud in a hotel room in July 1873. The hotel in question, the H��tel A la ville de Courtrai on the rue des Brasseurs, is no more (it closed in 1979). Baudet describes it as having been a ���dive near the Grand-Place���, Brussels���s historic centre. On site today is a lace shop whose owners Rose and Jean-Pierre, writes Baudet, ���hate [the] marble plaque erected in 1991 by the French Community of Belgium���. It reads: ���Here stood the H��tel A la ville de Courtrai where, on 10th July 1873, Paul Verlaine wounded Arthur Rimbaud with a revolver shot���. According to Baudet, the owners of the lace shop are unhappy with the tourists who constantly ask them who Verlaine and Rimbaud were ��� they obstruct the entrance to the shop, apparently. Baudet remarks pointedly that the owners are Flemish. Not French-speakers by choice, in other words. Maybe that explains their sense of irritation.

The offending revolver formed the centrepiece of a superb exhibition last year about Verlaine���s time in Belgium, including his period of incarceration in the nearby city of Mons. As Baudet reminds us, it wasn���t an entirely negative experience for the poet: he was exempted from hard physical labour and was provided with writing implements; he also underwent a profound religious conversion. The poetry he produced in this period of religious fervour was, as Baudet writes, ���a long way from the Sonnet du trou du cul composed two years earlier to shock the Parnassian poets, guardians of classical rhyme, the pisseurs de copie, as Rimbaud called them���.

August 24, 2016

I am a city state

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

To help us with our editing work at the TLS we make ample use of the New Oxford Dictionary for Writers and Editors (ODWE). In it we find confirmation, for example, that proofreader is one word and unhyphenated, as is postmodern, but that post-structuralism retains its hyphen; and that Schadenfreude remains italicized (maybe it���s time to lower-case and romanize it; it���s in common usage after all, arguably as common as doppelg��nger, which ODWE doesn���t italicize).

I���ve been here so long that I really shouldn���t need to consult ODWE any more ("two words, one word in US"), but I tend to forget whether city state and nation state (are you still reading this?) are both unhyphenated. Well, nation state appears as two words and I���ve added city state myself in two words to my copy (I guess it appears less frequently than the former, and usually with reference to Renaissance Italy). But then it often seems to be rendered thus ��� city-state ��� in monographs on Renaissance Italy . . .

���I am a think tank. Am I hyphenated?���, a neighbouring editor might ask. To which the reply will come from somewhere around these parts: ���two words���. Yes, it���s all rather sad I know, but then aren���t most workplace (one word) rituals?

Although very useful, ODWE can be infuriating in its indecision ��� given that it���s supposed to be a style guide; in the current edition, for example, Quran is (also Qur���an) var. of Koran. Well, which is it? (We favour Qur���an.)

Meanwhile here, at random, are a few of its unusual entries, none of which I���ve ever had to make use of:

abbatial relating to an abbey, abbot, or abbess

pinking shears, pinking scissors (two words)

beeves see beef

furmenty use frumenty

frumenty dish of hulled wheat boiled in milk (not furmety)

furmety use frumenty

armhole (one word)

followed by

armiger person entitled to heraldic arms

pademelon (also paddymelon) small wallaby

cottar (also cottier) hist. tenant of a cottage

bancassurance (also bankassurance) selling of insurance by banks

We have water biscuit, water boatman (two words) but no water bottle

Ofwat is the Office of Water Services, a regulatory body (one cap.)

oilcake, oilcan, oilcloth are all one word, but oil drum (two words), while oilfield, oilseed and oilskin are all one word

Oleiferous producing oil

Oligopsony market with a small number of buyers

Electuary arch. Sweetened medicine

You might look up wig-maker and instead come across ���wigeon (also widgeon) a kind of duck���. Further up the column, we find wideawake (not to be confused with wide awake), ���soft felt hat (one word)���.

I���ve lost count of the number of times I���ve looked up ���coffee house��� (does it need a hyphen?) only to find it���s not in the ODWE. Instead I find ���coffee bar, coffee cup, coffee shop, coffee table��� (all pretty obvious), followed by ���cofferdam watertight enclosure in construction work (one word)���.

Then there are the Latin phrases that I repeatedly have to look up (partly to remind myself of what they mean) such as: sub specie aeternitatis viewed in relation to the eternal (L., ital.).

I recently read Eben Venter���s brutal novel Trencherman (first published in Afrikaans in 2006 (the English translation was reviewed by Elizabeth Lowry in the TLS, May 13, 2016). The translator Luke Stubbs provides an essential glossary of Afrikaans and Xhosa terms that appear in the novel. But why, I wonder, do witblommetjie (���a small Karoo bush with white flowers���) and ankerkaroo (���small Karoo bush���) appear in the text in roman whereas in the same paragraph kerriebossie (���small Karoo bush that has a strong curry smell���) is italicized? My pedantic reader���s brain was puzzled by this. Maybe it's just an oversight. All the same, it���s terrible to always be reading novels through the lens of a proofreader.

August 22, 2016

A nosy Parker

"Shared Fate (Oliver)", 1998 �� Cornelia Parker. Photograph by Dan Weill

"Shared Fate (Oliver)", 1998 �� Cornelia Parker. Photograph by Dan Weill

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

���I like objects or pictures with a caption���, the British artist Cornelia Parker told us a few weeks ago at the Foundling Museum in Bloomsbury, ���or I like to switch captions around.��� It���s no surprise, then, that she has curated a playful, object-and-story-based exhibition there, having enticed her Royal Academician friends, as well as famous writers and musicians, to respond to her theme of ���found���.

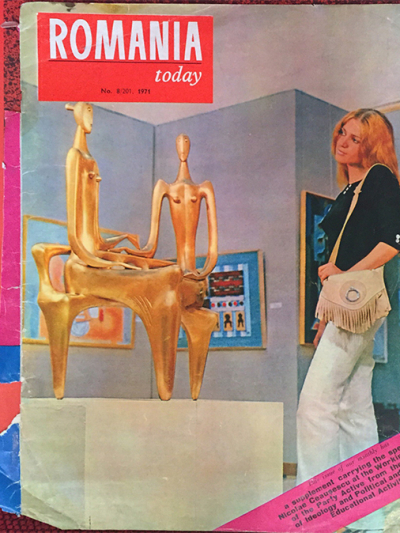

Displayed among the galleries��� permanent collection, these ���found��� works cleverly interact with what���s already there: hung between several oil paintings of austere wigged men, for example, we see the word ���FEELINGS��� made out of white neon strip-lighting by Martin Creed; Dorothy Cross���s wormy calcified bottle, discovered when she was deep-sea diving, is positioned under a traditional nautical painting; several copies of Romania Today (an English-language magazine promoting Nicolae Ceau��escu���s Communist regime) from Jarvis Cocker are accompanied by his description of how, one day in Bristol in 1985, he came across a bin bag full of the magazines ��� the garish, ���pumped up��� colours would later influence the look of his band Pulp; and all alone, in the corner of an ornate room, sits Gavin Turk���s ���Nomad��� (2002), a bronze cast of a sleeping bag that���s been meticulously painted to resemble the synthetic material of the original, with a timely blurb about homelessness, the refugee crisis, and the Foundling���s own history as a charity caring for abandoned children.

Part of Parker���s inspiration for the exhibition came from this history: set up in 1739 by Thomas Coram, the Foundling Hospital was supported by William Hogarth (who encouraged leading artists to donate work to the hospital, thereby establishing it as Britain���s first public art gallery) and George Frideric Handel (who gave an organ and conducted benefit concerts of the Messiah every year in its chapel). Parker was fascinated by the thousands of eighteenth-century tokens (small objects, such as engraved pennies, or swatches of embroidered fabric) left behind with the babies by the mothers as a means of identification should they ever return to claim their child.

Almost 300 years later, Parker is doing something similar in her work: ���I���m not trying to represent; I���m using the things themselves to stand in for other things���. Taking everyday objects laden with cultural meaning, she subjects them to a process (blowing up, flattening down etc) to make them unfamiliar and unfathomable, often adding an ingenious caption. (On the rooftop of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, you���ll currently find her ���Transitional Objects (PsychoBarn)��� ��� the fa��ade of a red barn, taken from upstate New York, held up by scaffolding. It���s meant to tap into traditional New England architecture and paintings by Edward Hopper, and also bring the Bateses��� sinister family house from Hitchcock���s black-and-white Psycho into colour.)

Her own pieces are some of the best here. ���Shared Fate (Oliver)��� (1998) is a doll cut in half ���by the guillotine that chopped off Marie Antoinette���s head. A tweak of history causes a fictional character to share the same fate as a real queen���, the caption tells us. One member of the audience didn���t approve of the work���s re-display in a former children���s home. ���Maybe I was more crass back then���, Parker responded. She found the toy in a Brick Lane shop ���and I wanted to give it a reason for having such an anguished look like that on its face���. On a more serious note, Parker continued, it shows how objects have a language. ���A decapitated doll has more impact displayed in here than in a white gallery space.���

Three deflated balloons in a glass cabinet (also by Parker) were another highlight for me: one is black, and entitled ���Breath of a Librarian���; another, ���Breath of a politician���, has ���Jeffrey for Mayor��� written on it; and ���Breath of a Scotsman��� is blue with a white cross. Alongside these sits the writer Deborah Levy���s blue bead with a broken wire thread: after her mother died, Levy collected lost beads and buttons from the streets. Coming across these curious pieces as you walk around the rather sedate Foundling Museum feels intimate, even intrusive.

Still from "FILM" by Michael Craig-Martin, 1962-3

Still from "FILM" by Michael Craig-Martin, 1962-3

On the top floor, there���s the only film Michael Craig-Martin has ever made. Found by his daughter in 2000 at the bottom of a trunk, the black-and-white 16mm film was created in Connemara on the west coast of Ireland in 1962, for his undergraduate degree. It features swirling waves, mariners sorting kelp, close-up abstracted shots of rural churches, relic-like buildings and a white-plaster Jesus on a wooden cross. Children, lined up on stone walls and staring directly at the camera, strike an inadvertent chord here, just like Parker���s decapitated doll. ���Really it���s a collection of high-profile discards, repositioned and looked at with a new eye���, she concluded. ���And I���m a nosy parker.���

"Found" runs until September 4.

August 17, 2016

More recommended reading from the literary journals

By MICHAEL CAINES

A word about literary magazines on this blog is overdue ��� sorry, we've been busy thinking about Sarah Moss, Soviet picture books and Chet Baker. What fine distractions are to be found in the summer crop of journals new and old, famous and fresh?

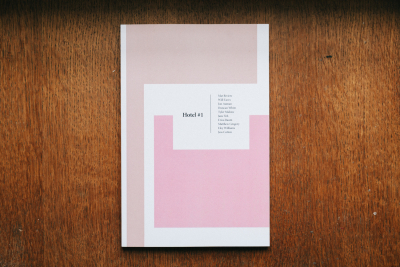

The freshest first, and a full disclosure: Hotel is a "magazine for new approaches to fiction, non-fiction and poetry" that is one issue old; and I had the pleasure of attending the launch for that issue, on the night after the EU referendum, because a former TLS editor contributed to it. Let us not dwell on Will Eaves unnecessarily. Instead, I can only say that Hotel's debut offers some "Notes on the Pink Hotel", by Jess Cotton, on pink paper ("I think of Rimbaud, far from his soft city rain . . ."), a couple of poems by Jane Yeh ("The maid thinks of cream cakes and breaking rules") and an excellent essay by Tyler Malone, "Sometimes He Left Messages in the Books", about the fate of David Markson's extensively marked-up library.

Markson's reputation stood sufficiently low at the time of his death in 2010 for the Strand Bookstore in New York to scatter his books along their 18 miles of shelves in the ordinary way, rather than keep them together. Every day for six months, Malone spent a few hours hunting around for them, and helping other enthusiasts find them, too ��� not an absolutely straightforward matter when The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas is "filed under T for Toklas instead of S for Stein", and books are (understandably) taking months to emerge from storeroom to open shelf. Yet "it is not just a delight to read Markson reading", Malone argues, referring to the marginal comments Markson made, the underlinings that led directly to passages in his books, "but it is truly indispensable to any study of the man and his work".

Online, meanwhile, the seventh edition of Prac Crit has appeared. This is a triannual "journal of poetry and criticism" that specializes in looking at contemporary poetry "up close" ��� it's an invaluable approach, I think, not least for anybody for whom the words "contemporary poetry" brim with menace.

Here are, for example, poems by Matthew Welton ("Think of it as the rubber ball we've hidden / in the fruit bowl . . .") and Katrina Porteous ("Imagine it a ruin . . .") that come with parallel critical responses (in these respective cases, an interview by Alex MacDonald and an essay by Jenny Holden). You keep the poem in sight in the left-hand half of the screen while scrolling through the prose on the right ("When we met by the stone lions in Market Square, Matthew was concerned with finding us a pub to talk in"). Kiki Petrosino, meanwhile, walks you through one of her own poems, "Scarlet", via thirteen footnoted stepping stones. Although maybe my metaphor's wrong here: it's more a case of taking a tour around the roots of a tree, discovering that one lies in childhood illness, another in the Super Mario Brothers video game, a third in a preference for the ampersand. "I prefer it for its visual dynamism; an ampersand looks both energetic & ornamental to me, like jewelry made from typewriter keys, spoons, or the innards of watches."

These are but striplings, though. Congratulations are due to Slightly Foxed: The real reader's quarterly ��� who is this real reader, I wonder, and what has she done with all the others? ��� for publishing its fiftieth issue this summer. Pleasures here include Laura Freeman's piece on Elizabeth David's elopement, which unexpectedly turned her from an actress into a cookery writer, and Richard Mabey's homage to the "swashbuckling" Round the World in Eighty Dishes by Lesley Blanch. There is also Michael Holroyd's warm appraisal of Dan Rhodes, which is surely destined to be excerpted for publication on the back of a paperback some time soon:

". . . his books would appeal, I believe, to many readers. But he avoids journalism, does not belong to any literary groups or contemporary school of writing and is very much an individual novelist. He neither pursues fame nor patronizes his readers. What he believes is what you get: sensitivity, humour, sadness and devastating shock. Sometimes I have been so saddened, so shocked, that I have stopped reading and put the book aside. But before long I am compelled to pick it up again and read on. And what I have read has found a place in my imagination."

What lies beyond fifty issues? Well, Granta recently reached no. 136 (with the theme "Legacies of Love") and Ambit hit no. 224. Not to get carried away, however, I'll close with a solemn nod to the Dublin Review (63 not out). Here, amid the contributions with eye-catching titles such as "The transhumance" and "Uncle uncle uncle uncle uncle", is Rob Doyle's "To the Point of Death", the record of an intellectual relationship. That's the dry way of putting it. Doyle writes about losing himself in "the overpowering, life-justifying rapture" of clubs and drugs, while taking philosophical succour from the works of Georges Bataille. In Paris (not the City of Lights but the "City of Condoms") Doyle makes a Bataille pilgrimage, heading for the Rue de Rennes, near Montparnasse, where the great man lived for a formative period of his life. Only later, as Doyle turns thirty-three, he realizes that he had felt older when he was younger, and Bataille had been the guide to see him through that gloomy period of his life. "If philosophers were musical sub-genres, then Bataille was death metal ��� and death metal was insufferable, its devotees a gang of dreary bastards." What fun it is, being in on this gradual process, without having to go through it yourself.

August 13, 2016

Where do we go from here?

Sarah Moss, 2015; credit: Ray Tang/REX/Shutterstock

By FR����A ��SBERG

Sarah Moss recently read from and discussed her new novel, The Tidal Zone (reviewed in the TLS of July 29), with her editor, Max Porter, at the London Review Bookshop. The book is about a stay-at-home dad whose daughter, at the beginning of the story, has a cardiac arrest; this results in a "narrative breakdown", as Moss describes it.

The psychological approach to narrative has become a popular subject in academia during the past two decades. Narrative is something fundamental to the self; it's an onward movement, but also a constructive process for memories and identity. It is the story, but also the telling. Having read the book, I wasn't all that surprised that Moss, an academic who completed a PhD in Romantic poetry, was preoccupied with the concept. "When you get sick," she said, "you go to the doctor." But the father's predicament is that he and his daughter have already been sent home from the doctor. There is no logical next step, no recipe to use: "I watched the monitor as if, eventually, I would learn from it what plot we were following". Moss wanted to capture the "beauty of ruinness" that comes with the failure of narrative ��� adding, "you can do that to sentences".

The discussion moved to national identity, which is also a kind of narrative. Moss taught at the University of Iceland in 2009, soon after the economic crisis, and saw how Iceland woke up a new country, betrayed and alienated, and therefore forced to reconstruct its identity (and consequently its narrative). The same is now happening in Britain after Brexit, Moss pointed out. Our inaction towards the refugee and war crisis is, in a way, a narrative breakdown. We are cooking our dinner at home when a bomb explodes on television and a Syrian citizen shouts: "Where is the world?" And we are completely at a loss. We don���t know a next step. We, like The Tidal Zone���s protagonist, have to reconcile our lives to the new information, and somehow work our way on from there.

August 11, 2016

From Leningrad to London

"Out with the mysticism and fantasy of children���s books". Soviet propaganda poster by Olga and Galina Chichagova

By BRYAN KARETNYK

On July 26, the House of Illustration on Granary Square hosted an hour-long talk, From Leningrad to London, to accompany their exhibition of Soviet picture books from the 1920s and 30s, several of which are on display in the UK for the first time. The evening���s speakers ��� the collector and publisher Joe Pearson and the artist Otto Graphic ��� were charged with the task of tracing the lines of influence left by these revolutionary children���s books.

The exhibition itself, curated by Olivia Ahmad, is impressive if compact. A visual treat for readers young and old, it comprises four rooms of eye-catching illustrated works drawn from Sasha Lurye���s enviable collection (which also formed the core of Julian Rothenstein and Olga Budashevskaya���s recent book Inside the Rainbow). The books are displayed alongside original sketches and paintings, with artwork by giants of Soviet illustration including Vladimir Lebedev, Vladimir Tambi and the Chichagova sisters, as well as such luminaries as El Lissitzky and Marc Chagall, who had taken up the revolutionary call to ply their trade in more "practical" endeavours. Entreated to rid Soviet youth of "the mysticism and fantasy" of the old order, artists and designers worked hand-in-hand with authors to supplant Baba Yaga and Koshchei the Immortal with the new heroes of Soviet life: construction, agriculture, transport and heavy industry. Visitors to the exhibition will even see Alexei Laptev���s beautifully illustrated fold-out Five Year Plan (1930) for children. But, as the exhibition demonstrates, there was much more to this golden age of Soviet children���s books than the strictly utilitarian: among the collection���s more striking examples are Lissitzky���s Suprematist-inspired About Two Squares (1922), an avant-garde allegory of the revolution itself, and Tambi���s haunting illustrations for The Book of Wrecks (1932), a macabre compendium of naval and shipping disasters. Books in other languages and in translation feature too, with Yiddish works by Leib Kvitko and Der Nister on display, as well as colourful Soviet editions of Walt Whitman���s "Pioneers! O Pioneers!" and Rudyard Kipling���s "The Elephant���s Child" (again, illustrated by Lissitzky).

![Vladimir Tambi, cover art for Book of Wrecks [Kniga Avarii], Moscow OGIZ, Molodaia gvardiia, 1932](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1470995281i/19988559.jpg)

Vladimir Tambi, cover art for Book of Wrecks [Kniga Avarii], Moscow: OGIZ, Molodaia gvardiia, 1932.]

Michael Czerwinski, head of public projects at the House of Illustration, introduced the evening���s speakers. Joe Pearson was first up. With infectious enthusiasm he described the revolutionary effect of Soviet children���s publishing on the British book market, which transformed the dowdy black-and-white print of contemporary children���s books by injecting them with colour and innovative design. The Soviet editions, he explained, were the result of a discerning publication process: expert commissioning committees, close collaboration of artists, writers and publishers, "focus groups" of young readers, and the latest in printing technology to ensure that the books could be produced to a high quality, in phenomenal print runs (often in the hundreds of thousands), and sold cheaply. The end result was a slick mass-production operation, intentionally designed to quicken the creation of new Soviet man. What could be farther removed from the stagnation of children���s books in Britain at that time, languishing in small print runs and keeping children in their protective bubble of fairy tales and neverlands?

All this began to change for Britain in the 1930s, Pearson said, when colour-illustrated books such as J. M. Richards���s High Street (1936) appeared for the first time. The signal moment, however, was the publication of the first Puffin Picture Book in 1940: the initial print run of 40,000 copies sold out in less than a month, giving publishers to understand that the picture-book business was a lucrative one. Puffin went on to commission a vast list, built largely around the same models as the Soviet series. Indeed, the changing social structures and much-needed orientation towards reconstruction in post-war Britain would chime conveniently with the books��� Soviet forerunners. Women-at-work books, for instance, which had been a staple of Soviet children���s books since the 1920s, now appeared in the UK, subtly reflecting changes in gender roles. At this point Pearson presented, to the audience���s delight, one example of a book on car mechanics ��� showing not a boy, but a girl with pigtails examining the pedals and gear stick (her knitting stowed safely in the glove compartment).

![A. Gromov, a spread from Stencils [Trafarety], Moscow OGIZ, Molodaia gvardiia, 1931](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1470995281i/19988560.jpg)

A. Gromov, a spread from Stencils [Trafarety], Moscow: OGIZ, Molodaia gvardiia, 1931

The artist Otto Graphic spoke engagingly of his admiration for the integrated design solutions found by the early Soviet illustrators. He also spoke with charming self-effacement and humour of his own trials and tribulations in attempting to reproduce their tricky stencil and autolithographic techniques, divulging to the audience several behind-the-scenes slides with examples of his efforts leading up to the completed works. The stencilling techniques had apparently given him particular trouble, so it was not without irony that he mentioned having spotted in the exhibition Alexander Gromov���s Stencils (1931), which teaches children how to make their own. "It���s in Russian," he lamented, "so unfortunately I can���t read it."

The talk closed with a discussion of the recent reaction against digital modes of design and production, and the resurgence of analogue photography, vinyl and niche printing. However, as one audience member astutely commented, this exhibition also sounds a cautionary note: Given these books��� raison d�����tre ��� to depict the future through the latest in technological innovation and mass communication ��� is there not perhaps something elegiac in today���s vogue for nostalgia?

The exhibition A New Childhood: Picture books from Soviet Russia runs at the House of Illustration, 2 Granary Square, King���s Cross, until September 11.

August 9, 2016

Little white cat

Ethan Hawke as Chet Baker in Born To Be Blue

By JONATHAN DRUMMOND

The new Chet Baker biopic (bioPIC or BiOPic?) Born To Be Blue, featuring Ethan Hawke as the troubled trumpeter, concentrates on the events of his life in 1966 and 1967. We don't see anything of his early breakthrough with Charlie Parker (who warned Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie: "You'd better watch out ��� there's a little white cat on the Coast who's gonna eat you up!") or his involvement in the innovative Gerry Mulligan quartet, or even the production of arguably his most famous record, Chet Baker Sings. Nor does it feature the last twenty or so years of his career, during which he released a number of successful records and toured Europe extensively in spite of his drug addiction. He died in 1988, after falling out of a hotel window in Amsterdam.

The opening scene shows Chet lying in an Italian prison cell high on heroin, reaching towards a tarantula crawling out of the bell of his trumpet. His addiction soon leads to a critical moment ��� a drug dealer smashes the teeth out of Chet's head with the butt of a gun. The film focuses on his subsequent struggle with drugs, his struggle to develop a new embouchure, and his struggle to maintain a relationship while staying clean. We really only ever see Chet as the shambolic junkie ��� constantly forcing his new false teeth back into his mouth; sitting in a bath, covered in blood, trying to produce a single note on his horn; unable to come even close to creating the kind of music for which he'd once been famous. While he is relearning his embouchure, he takes a regular gig in a pizza restaurant with a local amateur quartet who tell him that he needs to practise more before they'll ask him back. He certainly seems to be following the advice given to him early in the film by Miles Davis (played by Kedar Brown), who, on hearing Chet's gentle swing and feminine vocals for the first time, tells him to "come back when you've lived a little".

What the film seems to lack is a lightness to go with the shade, any release to go with the tension. When studying jazz, in a former life, I was told that these things were necessary in order to create an engaging narrative. The irony is that Chet's playing was filled with these qualities. Every improvised line he played had an arc ��� a beginning, an end and invariably a beautiful and interesting way of linking the two together. His linear improvisation had a melodic nature of its own.

In jazz, you generally play the melody, then improvise over the harmonic structure of the piece, then play the melody again to finish; the tune provides a beginning and an end, and lends the improvisation a greater context. If only Born To Be Blue gave us something similar: it focuses on one brief period of Chet Baker's life, and doesn't let us hear the whole tune.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers