Peter Stothard's Blog, page 9

April 26, 2016

Reading like Woolf ��� across the Great Divide?

"Found on the Shelves": you may have already spotted this pocket-friendly series of little books in the bookshops. A collaboration between the ever-elegant Pushkin Press and the London Library, it includes a volume called On Reading, Writing and Living with Books that celebrates the prestigious literary history of the London Library itself by offering a selection of short pieces by former members: Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Leigh Hunt and E. M. Forster. But also: Virginia Woolf's essay "How Should One Read a Book?". It's described here as simply "published in 1932", although its earliest version is a talk Woolf delivered at a school in the mid-1920s. It gives the impression, in any case, of the maturest consideration, so that the title's simple-sounding question ��� how should you read a book? you pick it up, open it, turn to the first page etc, answers every smart alec or alice, first time round ��� actually gives on to a prospect of deep critical wisdom . . . .

It begins with an impression of freedom: "what laws can be laid down about books?" The reader in the library mixes with a "heterogeneous company", and mustn't make unreasonable demands that every book must conform to one standard or another; "rubbish-reading", picking out whatever catches the eye in inartistically devised memoirs and the like, has its satisfactions. Eventually, though, Woolf observes, we have to admit that "facts are a very inferior form of fiction", and it's time to seek out the "varied art of the poet" and the equally abstracted pleasures of fiction. Quoting and comparing various verses leads to an unexpected turn in the path:

"'We have only to compare' ��� with those words the cat is out of the bag, and the true complexity of reading is admitted. The first process, to receive impressions with the utmost understanding, is only half the process of reading; it must be completed, if we are to get the whole pleasure from a book, by another. We must pass judgment upon these multitudinous impressions; we must make of these fleeting shapes one that is hard and lasting. But not directly. Wait for the dust of reading to settle . . . . we are no longer the friends of the writer, but his judges; and just as we cannot be too sympathetic as friends, so as judges we cannot be too severe. Are they not criminals, books that have wasted our time and sympathy; are they not the most insidious enemies of society, corrupters, defilers, the writers of false books, faked books, books that fill the air with decay and disease? Let us then be severe in our judgments; let us compare each book with the greatest of its kind. There they hang in the mind the shapes of the books we have read solidified by the judgments we have passed on them ��� Robinson Crusoe, Emma, The Return of the Native. Compare the novels with these ��� even the latest and least of novels has a right to be judged with the best . . . . we may be sure that the newness of new poetry and fiction is its most superficial quality and that we have only to alter slightly, not to recast, the standards by which we have judged the old."

A dichotomy then emerges, between the judgements that arise out of this freely explored world and the judgements of the "gowned and furred authorities of the library". Those authorities would seem to "decide the question of the book���s absolute value for us", only "there is always a demon in us who whispers, 'I hate, I love', and we cannot silence him": "we cannot suppress our own idiosyncrasy without impoverishing it". The true critic may require the "rarest qualities of imagination, insight, and judgment", but the rest of us can still chip in. "The standards we raise and the judgments we pass steal into the air and become part of the atmosphere which writers breathe as they work. An influence is created which tells upon them even if it never finds its way into print. And that influence, if it were well instructed, vigorous and individual and sincere, might be of great value now when criticism is necessarily in abeyance; when books pass in review like the procession of animals in a shooting gallery, and the critic has only one second in which to load and aim and shoot and may well be pardoned if he mistakes rabbits for tigers, eagles for barndoor fowls, or misses altogether and wastes his shot upon some peaceful cow grazing in a further field."

Unfortunately, I failed to quote any of this essay in the course of my contribution to a recent and otherwise superbly informative, insight-rich symposium in Cambridge called Books in the Making, hosted by the Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities (CRASSH to you and me). The symposium's subject was "contemporary literary production", from Creation (represented here by the novelist Ben Markovits and the agent Rachel Calder, among others) to Publication (John Oakes of OR Books, Antonia Hodgson of Little, Brown et al) to the part where I came in, Reception (represented most ably on this day by Stephen Burn). Woolf's library, lawless yet inevitably inviting judgement, belongs to the world of Reception.

Creation and Publication have a complicated relationship with Reception's endless empire; I tried to describe it as circular. Book reviews don't necessarily translate into book sales ��� book prizes are more likely to do that, in their direct and hysterical way. Perhaps that's because book reviewing is in a bad way at the moment, as one publisher suggested, much as Woolf did in her time. (As Punch was never as funny as it used to be, so, apparently, is reviewing never as incisive as it once was. Fatuously sure of himself, the publisher nonetheless failed to reinforce his point with a single example.) Or perhaps, regardless of the state of current criticism, we should rather say that the most elusive aspect of the cycle through which books are made is that invaluable process described by Woolf ��� a process of judgements not so much mandarin as commonplace stealing into the air, and never going near print at all. Or even Goodreads.

Reception is as lawless as Woolf's library. While authors and publishers conventionally work to a deadline, readers have none. A book can go on the rubbish heap, and be all but forgotten until a common reader happens to fancy redeeming it. Influence can also be first-hand or not; you can catch a Jamesian chill from a ghost story by one of his imitators. Nobody can read everything, of course, and few are gifted with all three of those three "rarest qualities" in equal measure ��� but changes in the literary atmosphere occur all the same, and those changes change in turn what gets written and what gets published. Ben Markovits touched on this subject while talking about Creative Writing as a university course and, in particular, about the dilemmas of an admissions tutor. A certain number of candidates, he observed, would offer samples of their work that confessed their immersion in the world of, say, Harry Potter; another lot would have vampires on the mind; he described the ones whose realism, if that's not too bald a way of putting it, he would find intriguing and most rare (that word again). Yet all could have potential, merely having reached his office by different routes.

"Nobody can read everything" ��� I've let the cat out of the bag myself. While Woolf's essay addresses the individual reader, Books in the Making concluded with Professor James English's lecture "Revisiting the 'Great Divide': The past, the future and the contemporary novel", as embedded above. After our various attempts to address large topics as individual witnesses, here was a machine-inflected view of fiction, as it is, on the one hand, "seized upon with positive attention by critics" and literary prize committees, and as it is, on the other, seized upon by "ordinary" readers. This "Great Divide" is so firmly established a part of literary history that even a computer, given a chance to analyze merely the vocabulary of 50,000 volumes of digitized poetry spanning one out-of-copyright century, can sort out the "prestigious, high-status volumes" from "everything else" with a success rate of 80 per cent.

There are other distinguishing features on both sides of the Divide. Among several fine examples of how data sets far beyond the scope of a single reader can be used to reveal the "hidden laws governing the distribution of social prestige", Professor English showed how significant a presence historical novels have become on prize shortlists; long before Wolf Hall, the (Man) Booker Prize started gravitating towards the past. Skip on to the forty-minute mark to see how bestsellers have remained predominantly contemporary in setting over the same period. And the key point is that this is not airily intuited but confirmed by mass analysis.

I wonder what any of this Reception talk meant to the novelists and publishers in the room. To an all-too-common reader, it was fascinating, but suggested that we're not quite so free to wander around the library as we'd like to think.

April 23, 2016

Football on stream

June 1984: Michel Platini holds aloft the European trophy after France defeated Spain by 2-0 in the Final. President Mitterrand is behind him on the left. Credit: Allsport UK

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

As France prepares to host the Euro championships this summer, it���s a sobering thought that it���s probably an event the country���s security services could happily do without. But on the field of play itself, the hosts have deprived themselves of their star striker Karim Benzema (Real Madrid), over the matter of a sex tape that implicated another player, Mathieu Valbuena. It���s an unsavoury episode with a suggestion of blackmail. The manager Didier Deschamps (captain of the World Cup winners in 1998, and of the European champions two years later) decided that it simply wasn���t possible to overlook Benzema���s errant behaviour.

France have hosted the European championships before: in 1984. They won. (It's worth bearing in mind that the two occasions when France have hosted a big tournament,1984 and 98, they've won. What price a hat-trick?) Their captain was also their leading goal-scorer (with nine of France���s fourteen goals in five matches), Michel Platini. I didn���t watch any of it ��� and was probably only vaguely aware that the event was taking place, even though I���d spent the first five months of the year in the country as a student. I don���t recall there being any build-up to the tournament. How the profile of the game has changed in the past thirty years! But I do have recollections of Platini���s subsequent stellar performances with the Italian club giants Juventus.

Platini is now principally known for his close alliances as director of the European organization UEFA with the disgraced former head of FIFA, Sepp Blatter. Indeed, Platini has been suspended from the game for eight years. It���s looking like a sad end to a glittering career in the game.

Will the writer Jean-Philippe Toussaint be attending any of this summer���s matches? Portobello are about to publish his Football, in a translation by Shaun Whiteside. It���s a short book ��� under a hundred pages (the French edition was brought out last year by Toussaint���s regular publishers Les Editions de Minuit).

Toussaint opens with a warning: ���This is a book that no one will like, not intellectuals, who aren���t interested in football, or football-lovers, who will find it too intellectual���. That���s characteristically playful of him. While we���re about it, what is an intellectual? It���s a term that seems constantly to require definition ��� and to defy it.

Football is only partly about football. We revisit the writer's childhood. Later there's a description of an encounter with Jeff Koons and his young family. Toussaint has been present at two World Cups ��� Japan in 2002 and Germany in 2006, but doesn���t describe the matches he saw in any detail (although the English edition includes his separately published Zidane���s Melancholy, a meditation inspired by that player���s sending off in what turned out to be his last game for France, the final against Italy in Berlin). Living in Brussels for many years (he is Belgian), Toussaint never attended a match, he reveals. In common with many who like the game, he doesn���t follow a team. His presence in Japan neatly coincided with a book promotion tour (several of his later novels are partly set in the country). But he describes in almost nerdish detail his journeys to and from the stadia, who he sat next to, how irritating they were, etc. It���s all quite entertaining.

Ronaldo (the first one) wheels away after scoring for Brazil against Germany in the final, Yokohama, June 30, 2002

Come the 2006 tournament, he applied online for several tickets and congratulated himself on his purchases only to be met with the message Ausverkauft (sold out). I can empathize: I had a similar experience with the 2012 Olympics in London when my ���purchase��� of tickets to six events yielded just one actual set of tickets. Watching sport live, it seems, has never been more popular.

By 2014 (Brazil) Toussaint is in his writer���s retreat on Corsica ��� no TV, no internet. He has come to work but he cracks and buys an internet package to watch a match on his laptop ��� ���en streaming��� in the French version ��� there���s a storm and he loses his connection. He tries the radio: there���s a power cut, just as a penalty shoot-out is about to take place. He finds an old transistor in the house ��� panic over; relief! How daft that football ��� twenty grown men chasing a piece of leather around a field ��� can have that effect on an intelligent individual.

April 22, 2016

Peak Bard

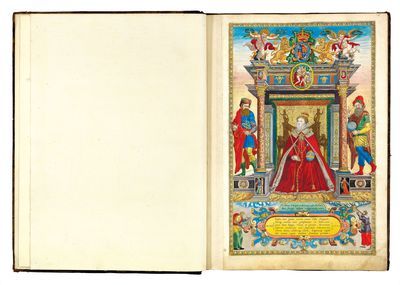

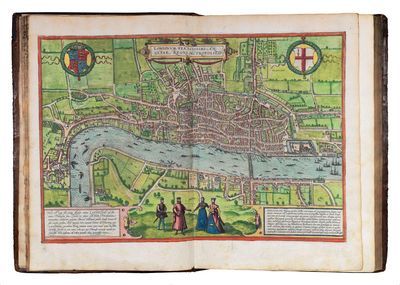

Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg, Civitates Orbis Terrarum, Cologne, 1585���1617

By MICHAEL CAINES

I took a tour of Shakespeare's England yesterday morning ��� without leaving central London.

It seemed like the right time to do it. The 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's death has inspired an extraordinary number of exhibitions and events. I feel as if I reached "peak Bard" some time ago, following the previews for By me William Shakespeare and the BFI's Shakespeare on Film season (where Sir Ian McKellen restated his view, as in his Richard III, that updated or contemporary costumes can help viewers to understand what's going on in the plays). Nevertheless, there has been much more to enjoy. . . .

I felt lucky to see the British Library's Shakespeare in Ten Acts for all the reasons given by Russ McDonald in this week's Shakespeare-inspired issue of the TLS. Between the BL and Somerset House, a Londoner can see pretty much every surviving example of Shakespeare's handwriting, including the pages of the collaborative play "Sir Thomas More" that are "thought to be" in Shakespeare's hand; there are also many excellent rarities such as the first quarto of Hamlet, Let this image from the Wooster Group's Hamlet of 2013 stand for that particular play's accreted layers of theatre history:

I'm not always convinced that curators under pressure to include interactive technology know exactly what to do with it, but this time it seemed to be well used, so that Harriet Walter, Peter Sellers, Mark Rylance, Stephen Fry and others could be seen offering animated accompaniments to the books, paintings, theatrical mementos and the rest. The only thing that left me uncertain was the montage of familiar portraits of Shakespeare that greet you as you leave the "prologue" to the exhibition and go down the stairs. It reminded me only of dodgy claims by various people to have found the true face of Shakespeare, and how uncertain and futile such proof-less pursuits can be.

The image of the writer is solidly represented at the Soane Museum's much smaller but also deeply enjoyable show "The Cloud-Capped Towers": Shakespeare in Soane's architectural imagination. The museum, formerly Soane's home, boasts a permanent Shakespeare Recess just off the main staircase, where the writer presides in the traditional likeness of a "self-satisfied pork butcher" (in J. Dover Wilson's snooty phrase).

It turns out that Soane's obsession with Shakespeare went deep: he collected copies of all four seventeenth-century folio editions of the plays, and bought two of the paintings commissioned for John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery. From the Shakespeare Gallery building itself, on Pall Mall, Soane drew inspiration for his Dulwich Picture Gallery, and he quoted Shakespeare in his Royal Academy lectures. The exhibition's guest curator Alison Shell, meanwhile, offered an intriguing suggestion: that, in the wake of the French Revolution, the Phrygian caps Soane put on the heads of the cherubs in the Shakespeare Recess were meant to symbolize the poet's imaginative freedom.

Not so hifalutin, but just as well selected for display, is a copy of The Frolics of Puck, a Shakespeare-inspired work by Soane's estranged son George. It appears to be quite an invidious object once you think about why father and son were estranged.

From the BL to the Soane to Daniel Crouch Rare Books: this might sound like a further scaling down, but actually the Bury Street specialists in maps and atlases have brought together a wonderful collection; and Rounded with a Sleep, an exhibition celebrating Shakespeare and his contemporary Cervantes, which runs until April 29, is well worth catching.

For a start, there is that tour of Shakespeare's England I mentioned ��� a tour in the form of Christopher Saxton's gorgeously coloured Atlas of England and Wales. Published in 1579, lavished with gold leaf and lapis lazuli, this sumptuous book was kindly opened for me, at first at this page:

Then we leafed through one county, and the next, until we had seen together, in a surprisingly rapt silence, all the forests of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, as well as the hills of the North and Wales, and the rest of Elizabeth I's barely united realm. All this, one notes, can be yours for a mere ��250,000.

The same generous soul who showed me Saxton's Atlas reminded me that the view of London and Westminster by Wenceslaus Hollar above the fireplace had the name of the Globe Theatre in the wrong place. Yet this engraved panorama of 1647 features convincing also has such as the man walking his dog in Southwark, mounted gentlemen crossing the old London Bridge and a ship listing heavily to one side in the middle of the River Thames. These details are easy to miss in a smaller reproduction, especially when one is concentrating on locating the Globe and that other obvious presence, the old St Paul's Cathedral.

Further wonders unfolded themselves: the 1768 French edition of Don Quixote plus more Cervantes in eight volumes; the fifth quarto of Hamlet (1637) which claims to be "Newly imprinted and inlarged" (don't they all?); the 1676 edition of John Speed's world atlas; the only known surviving copy of Luis Teixeira's planisphere of 1604, featuring depictions of exotic beasties from every continent (here a tribe of noble savages, there an elephant in a serpentine fix). I admit that such exercises in cartography enthralled me. It's the thought of Cervantes and Shakespeare, in their different places but the same era, looking on sea beasts and listing ships alike, perhaps. It's the inkling this exhibition gave me that knowledge and imagination, in atlas terms, are so near allied. As in Teixeira's map ("universalis et accurata tabula"), with its postulated polar continent and Ethiopian ocean.

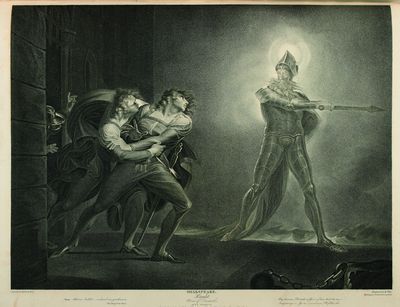

Otherwise: visitors to the National Theatre are no doubt booking themselves in for the 5 Hamlets tour; visitors to the south bank of the Thames this weekend will find themselves following the trail of the Complete Walk, a series of films to be shown along the South Bank, laid by Shakespeare's Globe; visitors to Stratford-upon-Avon will find themselves drawn to the "introductory" Famous Beyond Words; or even tonight's performance in Holy Trinity Church of Garrick's reconstructed "Ode", first performed in Stratford in 1769, and a new Shakespeare Masque with words by the current Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy, and music by Sally Beamish; while visitors to the Bodleian Library are, I hope, even now dropping in on Shakespeare's Dead, a suitably punning, morbid Weston Library exhibition. Sticking with the Hamlet theme, and another product of the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery, here's the Bodleian's copy of an engraving based on Henry Fuseli's version of the ghost appearing to his son:

�� Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

To think that, amid all this tremendously active Bardolatry, there remains the option of staying home, raising a glass ��� and reading a play.

Whichever option you take, do consider making time in your busy schedule to listen to today's episode of TLS Voices. It features an illuminating chat between Ben Okri and Kamila Shamsie, recorded at the Radisson Blu Edwardian, Bloomsbury Street hotel on April 19, as part of the reliably entertaining and engaging Hidden Prologues series that has been mentioned before on this blog. In keeping with my previous post about Charlotte Bront�� and the inspiration she provided for later writers, I suspect that Lunatics, Lovers and Poets ��� the collection of stories to which Okri and Shamsie have contributed (and which is reviewed in this week's TLS) ��� demonstrates how certain great authors can shape the literary future. Listen and learn, as I have toured and been amazed . . . .

April 21, 2016

Charlotte Bront��: a ���great literary gift���

Evert A. Duyckinck; after a drawing by George Richmond

By MICHAEL CAINES

Some writers float in and out and then back into fashion (no more about John Williams's Stoner for now, please); some sink like the obviously solid objects they are; others seem to become lily pads fit for the critical frogs to bask on, thinking their fine, fly-focused thoughts. (There must be more types, but mercifully I'm out of rubbish metaphors.) Charlotte Bront��, in case you were in any doubt, seems never to have been in any danger of losing buoyancy ��� she was born 200 years ago today, and has been assured of some kind of attention since 1847 at least, when the publication of Jane Eyre by "Currer Bell" triggered such excitement and curiosity about the pseudonymous author. The novel's immediate reception is well known: Elizabeth Rigby's damning of its "gross inconsistencies and improbabilities", as well as Jane's "unregenerate and undisciplined spirit"; G. H. Lewes's enthusiasm for this "utterance from the depths of a struggling, suffering, much-enduring spirit". What happened after that?

Well, if you really want to know the answer to that question: you could do worse than leafing through the pages of the TLS archives. The first and most significant piece about Charlotte Bront�� being Virginia Woolf's anonymously published essay of a hundred years ago:

". . . there is one peculiarity which real works of art possess in common. At each fresh reading one notices some change in them, as if the sap of life ran in their leaves, and with skies and plants they had the power to alter their shape and colour from season to season . . . . the novels of Charlotte Bront�� must be placed within the same class of living and changing creations, which, so far as we can guess, will serve a generation yet unborn with a glass in which to measure its varying stature. In their turn they will say how she has changed to them, and what she has given them . . . . At the conclusion of Jane Eyre we do not feel so much that we have read a book, as that we have parted from a most singular and eloquent woman, met by chance upon a Yorkshire hillside, who has gone with us for a time and told us the whole of her life history . . . ."

Woolf ends by referring to Bront��'s "great literary gift", her achievements as a "writer of genius" but also a "very noble human being". (Writers aren't always so complimentary about one another, even/especially when separated by such a distance in time, situation and aesthetic.)

From there, you proceed to rediscoveries such as The Twelve Adventurers and Other Stories (1925) and The Spell: An extravaganza (1931) ��� tales from the youthful realm of Zamorna, and the latter the work of another alter ego, "Lord Charles Albert Florian Wellesley". Then there are the scholarly companions such as E. M. Delafield's contemporary life records (1935), the various new editions of the novels and the poems, the critical and biographical studies . . . There is Q. D. Leavis working out the dating of Jane Eyre in 1965 and Rosemary Ashton calling in passing, in 1988, for a new edition of the letters, which comes along eight years later, just after Lorna Sage has reviewed Lyndall Gordon's biography ("Repression remains the keynote, but it's repression squared, repression chosen and embraced").

And that takes us almost to the present day: Claire Harman on a case of mistaken identity, Mark Bostridge on the Bront�� "conmen", Samantha Ellis on relics of the Bront��s and how their admirers are to interpret them. (And for those who enjoy such curious connections: Thea Lenarduzzi on the umlaut-free "Duke of Bronte".)

And it wouldn't do to omit the nineteenth-century forerunners to the recent National Theatre Jane Eyre, a history of which was reviewed by Judith Flanders in 2007, not to mention Jean Rhys's Wide Sargasso Sea, which was reviewed for the TLS in 1966 by a certain Mary-Kay Wilmers. Is this something else you can say about remarkable books and their remarkable creators? That readers' reactions will take the strangest turns. Into academic studies and guides for the literary tourist, yes ��� but back into fiction, too.

April 18, 2016

We Will Rock You

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

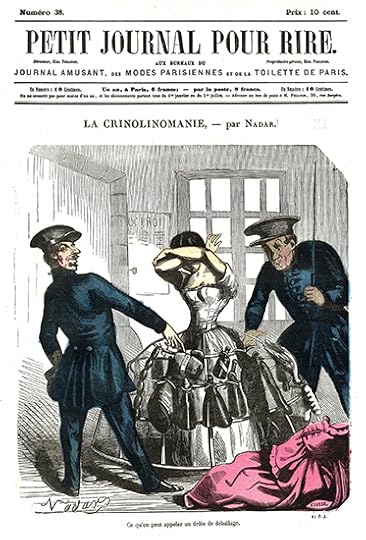

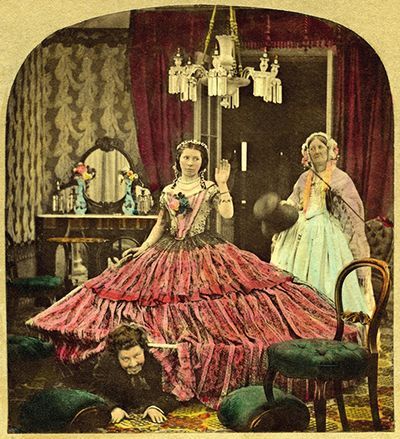

On Thursday night I watched Brian May emerge from underneath a woman���s skirt. Being on stage, commanding an audience ��� it���s nothing new for Queen���s lead guitarist. What is new is his focus on Victorian crinolines or, to be more precise, stereoscopic photographs of them.

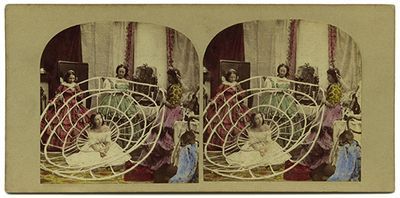

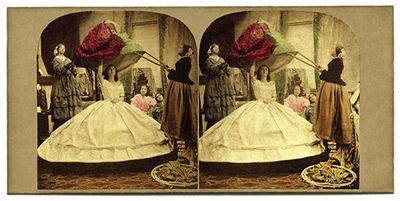

The craze for these undergarments in the mid-nineteenth century coincided with the invention of the stereoscope, May told us last week at the launch of his new book, Crinoline: Fashion���s most magnificent disaster, co-written with Denis Pellerin (they call it a ���disaster��� because the undergarment was a significant fire hazard: there were around 300 deaths a year from fire accidents during the crinoline���s peak). Stereoscopic cards, dubbed by the press as the ���Poor man���s picture gallery���, presented scenes, such as the Egyptian pyramids and crocodiles, in life-like 3-D to a public that had never seen or experienced anything quite like it before.

According to the London Stereoscopic Company (May is responsible for reactivating it), stereoscopic images can be created using a normal camera: first, capture the subject while you are standing on one leg, then transfer your weight to the other leg and capture the subject again. This gives you two views of the subject, taken from positions roughly the same distance apart as the eyes are; once these images are mounted side by side and seen through a stereoscopic viewer, they���ll give a 3-D rendering of the subject. (A greater distance between the first capture and the second will achieve an exaggerated stereo effect.)

At Christmas in 1857, ���Mysteries of the Crinoline��� (examples above) was one of the most popular series of stereoscopic pictures sold. Crinolines clearly caught people���s imaginations, especially when viewed in stereo ��� a format that is all about volume, depth, space; just like the crinolines themselves. In its first incarnation during the 1830s, the crinoline was a petticoat stiffened with horsehair (from the French crin) worn under a skirt. It became heavier and more voluminous through layering, which prompted a short-lived inflatable air-hoop version (prone to punctures and emitting rude noises) in the late 1840s, until the recognizable crinoline cage ��� the ���independent carcass��� ��� came into being, with hoops made from whalebone, cane or steel.

One interesting chapter in Crinoline concentrates on their manufacture. The growing demand for steel petticoats triggered a boom in England���s steel industry, and cartoons show blacksmiths at work (the curious captions include ���Locksmith to the Ladies��� and ���Ladies Tailor���). ���While the people down South were complaining about this ridiculous fashion���, the authors write, ���Sheffield and Birmingham manufacturers were rubbing their hands with glee, and secretly wishing it a long prosperous reign.���

Crinoline smuggling across borders was a common pursuit. A few of the items found hidden beneath women���s petticoats by the police are listed here, including obscene pictures; a turkey; twelve partridges; a hare and three rabbits; 32 lbs of tobacco; 22�� lbs of cigars; counterfeit money; four bottles of brandy and eight flasks of Eau de Cologne; 30 lbs of gunpowder; weapons (during the American Civil War); banned books and magazines (Henri Rochefort���s La Lanterne).

The most famous crinoline wearer was probably the Empress Eug��nie de Montijo, the wife of the French Emperor, Napol��on III; and May and Pellerin���s book contains some very funny contemporary reactions to her. Here���s one from Lloyd���s Weekly Newspaper on Empress Eug��nie���s visit to England in September 1856:

���A little reflection will convince even the English doubter that the influence of the Empress of the French upon English feelings and English customs, is far greater than that of any possible policy on the part of her astute and saturnine lord, the Emperor. If the policy of the Emperor has led to the alliance of Englishmen and Frenchmen, the example of the Empress has undoubtedly produced the isolation of Englishmen from Englishwomen. We, of course, allude to the crinoline, or horse-hair petticoat, first endued [sic] as a delicate device by Eug��nie, and immediately adopted by hundreds of thousands of most thinking spinsters, wives, and widows, of England . . . . Eug��nie has reduced the British bonnet to the dimensions of a scallop-shell, and expanded the British petticoat to the size of a cricketer���s tent.���

And what was Napol��on���s opinion of his wife���s fashion choice? Apparently he expressed it to the Stamford Mercury three years later:

���In the midst of all the serious combinations in which the Emperor is plunged, it is still delightful to observe that time remains for summer trifling. Thus, we learn that the Emperor, with that tenacity and perseverance for which he is distinguished, nothing daunted by the signal defeat he has sustained, both at Paris and St. Cloud, in the war he so imprudently waged against crinoline, has renewed the combat at Biarritz, and has maliciously taken to driving a low, narrow Victoria, with two ponies, instead of the high britchka he has been always accustomed to sport at the seaside. This new taste, although pouted at by the Empress, on its first adoption, has since become tolerated; and, certainly, the crinoline has diminished considerably, as it is observed no longer to hang over the side, and to draggle on the steps, as it did at first. The Emperor laughs slyly at the silent change which is gradually taking place, and has already expressed a hope that, before the Court returns to Paris, the eye of the Empress will have become accustomed to the diminished size of her skirts, that her Majesty will no longer be able to tolerate those of still disproportioned, though already diminished volume, which she will find the fashion yet on her arrival.���

Like Marie Antoinette almost a hundred years before her, Empress Eug��nie claimed that these lavish and innovative dresses were her ���political outfits��� ��� a way of promoting and supporting France���s economy. We all know how it ended for the former. But the latter died aged ninety-four, having been a forthright campaigner for gender equality (she pressured the Ministry of National Education to give baccalaur��at diplomas to women, and tried ��� unsuccessfully ��� to persuade the Acad��mie fran��aise to elect George Sand as its first female member). It seems her husband���s duress didn���t quite pay off.

April 15, 2016

After Frankenstein

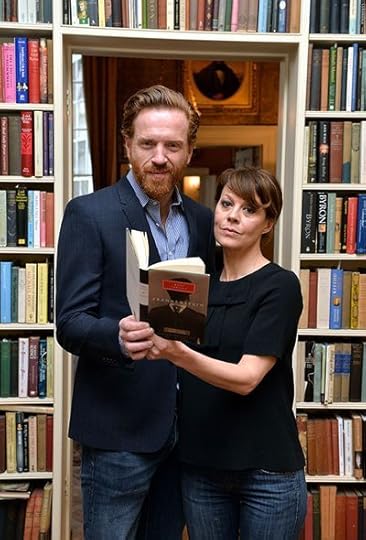

Damian Lewis and Helen McCrory; credit: Anthony Harvey/Getty Images

By SAMUEL GRAYDON

On entering 50 Albemarle Street, I felt as Ali Baba might have as the stone was rolled back from the mouth of the thieves��� cave. For an inconspicuous white town house, a minute���s walk from Green Park underground station, it certainly held more than its fair share of treasures. This was John Murray���s house and, from 1768 to 2002, it was the site of operations for the publisher that bears his name. I was directed up a wide staircase to the first floor where, in a room with grand bookshelves and gold wallpaper, lay a spread of tea, coffee, pastries and fruit (and, oddly, Bloody Marys). This was the ���Frankenstein Breakfast��� of the Keats-Shelley Memorial Association. Evidently, Frankenstein went for the Continental.

We were celebrating the winners of the 2016 Keats-Shelley Prize for poetry and essays on the theme ���After Frankenstein��� (for the bicentenary of the publication of Mary Shelley���s novel), and the winners of the Young Romantics Prize, for sixteen- to eighteen-year-olds, now in its second year. The Association had organized a reading, by the actors Helen McCrory and Damian Lewis, of extracts from Frankenstein intermingled with extracts from Shelley���s diary, arranged by the poet Pele Cox.

We assembled around the fireplace in which Byron���s manuscripts were burnt. Before the actors took the floor, the winner of the Young Romantics Prize, Riona Millar, aged sixteen, gave a reading of her sonnet, read under the watchful portraits of Coleridge, Byron and Thomas Gray:

Wreathed in laurels; glossy leaves unfurl, coiled,

The great pale gloaming thing unravels limbs,

Grins, hitches weeping gums wide, growling hymns,

Praising Father, Master, he who slaved, toiled

To build this monstrous structure ��� he is soiled

With these grimly yellowed stains, he who brims

With boundless love and wonder ��� awed, he skims

Round flat stones through his father���s throat ��� unspoiled.

The night, a temptress, plucks his peeling heart,

Wet, from his dappled chest, as moonlight blinds

Him; stumbling, mismatched, made up of spare parts

And engine oil. He trips, and falls. He finds

Great pale gloaming blooms that feed on the moon

He wakens not, with frail blossoms strewn.

This was swiftly followed by McCrory and Lewis���s performance, which, not unexpectedly, was captivating; Lewis emphasized the erudition and intelligence of the monster, and McCrory the coldness of Frankenstein: aspects of both characters that dramatizations of Shelley���s work often leave unexplored. Cox���s choice of extracts subtly drew out the shared role of the author and Frankenstein as ���creator���, allowing for a few moments when it was not apparent whether it was Shelley or her character who was speaking. But it is this plurality that plays such a part in Frankenstein���s success; man is monstrous and monsters humane ��� we are created and creators and we may hate and love in equal measure.

Listening to these readings, I was reminded that it is Frankenstein, and not "She Walks in Beauty", Don Juan, "To A Skylark", or even "Ozymandias" that is the best remembered work of all the writers who shared the Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva, 200 years ago. It would seem that it is easier to find an awesome terror in one���s own monstrosities than in the slopes of Mont Blanc, where Percy Bysshe Shelley discovered it.

And so, with sublime thoughts, I stepped out onto Albemarle Street again, leaving the treasures of the Romantics to themselves. I felt as though I should have said ���close sesame��� as I left.

Damian Lewis, Will Kemp, Riona Millar and Helen McCrory; credit: Anthony Harvey/Getty Images

April 12, 2016

Malta's cultural crossroads

By RUPERT SHORTT

Before visiting Malta a few days ago, I���d thought of it as a place of many quiet charms, but few if any superlatives. I was only right about the charms. Among other things, I���d failed to grasp the power and reach of the Knights of St John, who ruled the island from 1530 to 1798, lavishing their wealth on a network of churches, palaces and fortifications that rival much of baroque Rome.

In any case, though, the country���s importance long predates the time of the Knights. First settled by Sicilian farmers in around 4000 BC, Malta and the adjoining island of Gozo contain clover-shaped megalithic temples built several centuries afterwards, but not unearthed until the Victorian era. Later in antiquity came periods of rule by the Phoenicians, Romans (under whose watch St Paul was shipwrecked on the island, c.AD 60), Byzantines, Arabs and Normans. After the last Norman king died without an heir in the late twelfth century, Malta was controlled by Swabians, Angevins and Aragonese in turn. It was a Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, who offered the Knights of St John a home on the island after they had lost their foothold on Rhodes to Arab invaders.

So Malta embodied principles of European integration long before they were conceived in Brussels. As a multinational force, the Order contained French, Spanish, German, Italian and English sections, each with a headquarters or Auberge. The mighty fortifications in Valletta and elsewhere are explained by Malta���s abiding vulnerability to attack. Turkish military assault during the mid-sixteenth century ended in the Great Siege of 1565, through which a large invading force was repulsed by a much smaller group of defenders.

Malta���s wealth under the Knights is readily explained. It was almost the first time that the island���s rulers had resided in situ. St John���s Co-Cathedral, built in the 1570s by Mattia Preti, makes St Peter���s, Rome, look plain. Among other treasures it contains Caravaggio���s ���Beheading of St John the Baptist���, the artist���s largest canvas, painted when he was exiled in Valletta for two years.

As well as visiting the prehistoric temples and two exceptionally well-preserved towns ��� Victoria on Gozo, and Mdina on Malta ��� I spent my evenings at some fine concerts. First came the European Union Chamber Orchestra at the Teatru Manoel in central Valletta, a much smaller replica of La Scala, Milan. The company performed Britten���s Simple Symphony, Mozart���s C major piano concerto K.415 ��� his third masterpiece in the genre by my reckoning, and a savour of the even greater miracles to come ��� Haydn���s humour-laden 34th Symphony, and a brief, stretching work by Joseph Vella, a local composer who was present to take a bow. Hans-Peter Hofmann conducted; the soloist was Charlene Farrugia.

Two nights later the Auris Quartet gave us spirited but exact renderings of Beethoven���s Op. 18 no. 1 in F, Haydn���s Op. 76 no. 2, and Shostakovich��� s third quartet, Op. 73. The highlight for me came on the second night, when the young Canadian pianist Jean Dub�� produced a feast of many courses. Things began a little inauspiciously with Busoni���s arrangement of Bach���s Chorale Prelude ���Nun komm der heiden Heiland���. The tempo was too brisk, leaving the inner voices of this exquisite work somewhat smudged. It also works better as an encore than an amuse-bouche. Dub�����s over-assertive approach to one sort of musical challenge leaves him well equipped for another, however. His account of works by Schumann (the Op. 18 Arabesque) and Liszt (the Ballade no. 2 and the Mephisto-valse no. 1) displayed a well-judged mixture of passion and thoughtfulness. I felt nothing but exhilaration to be taken out of my comfort zone in modern works including Jean Cras���s ���Paysage maritime��� and ���L���Astre de l���amour��� by Demis Visvikis (b. 1951).

That these concerts were taking place in first-class venues ��� the Auris Quartet performed in the fresco-filled main hall of the National Museum of Archaeology ��� is a sign that Malta enjoys a sophisticated present as well as a rich past. Another such sign came at the Grand Master���s Palace, where an exhibition of manuscripts boasts material never seen outside the Vatican Library before, including one showing the secret code by which Pope Alexander VI communicated with his nuncios around Europe during the late fifteenth century.

The impression is buttressed by statistics on immigration (high) and social well-being (also high). Few spots around the Mediterranean in my experience combine cohesion and cosmopolitanism with such success. As for the Knights of Malta, they survive and thrive. Expelled by Napoleon ��� whose own defeat presaged the long period of British rule ��� they set up new headquarters in Rome, abandoned their martial past, and now sponsor medical missions in more than a hundred countries. Lately the organization has spent much energy on rescuing African migrants at risk of shipwreck as they strive to reach southern Europe.

The Grand Master's palace

April 11, 2016

Up the Republic!������������

By DAVID COLLARD

The author Neil Griffiths runs an engagingly low-tech YouTube channel on which he delivers informal off-the-cuff literary monologues straight to camera, occasionally swigging from a glass of red wine. While preparing a broadcast about his favourite novels of 2015 (see above), he realized that they had all originated with small independent publishers and this was, he says, "a Damascene moment that turned me into an evangelist".

Griffiths brings a convert's enthusiasm and energy to the publishing revolution that has emerged over the past few years ��� an equivalent, if you like, of micro-breweries, artisanal bakeries and hipster pop-up bars.

Griffiths's Betrayal in Naples (2004) won the Writers��� Club First Novel Award, and Saving Caravaggio was shortlisted for the Costa Best Novel Award in 2007. At the end of February this year, after mulling over that Damascene moment, he launched the Republic of Consciousness Prize for Small Presses, open to UK and Irish publishers employing no more than five full-time members of staff. Each publisher can submit a novel or single-author collection of short stories. A shortlist of eight books, decided by a group of independent booksellers, will be confirmed at the end of the year, and the winners announced in February 2017. Griffiths freely admits there is a "selfish reason" for launching the prize ��� he wants his third novel Family of Love to be published by an independent publisher because it is, he says, a "subtle" book about faith that would be "difficult for a major publisher to get on board with" (Griffiths's previous novels were published by Penguin).

Griffiths defines the "Republic of Consciousness" as a "writer's attempt to deliver us into the consciousness of another person, to take us from being mere witnesses to a character���s behaviour to participating in their lived experience [and] the re-creation of a perceived world without any mediating voice". Not always the sort of thing one finds in mainstream middlebrow fiction, but precisely the kind of writing that excites Griffiths and those of us who share his taste for (as he puts it) "hardcore literary fiction and gorgeous prose". Galley Beggar Press (which published Eimear McBride's debut A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing and Alex Pheby's Playthings) is among the independents most admired by Griffiths, but there are many others, all punching far above their weight: Fitzcarraldo Editions (publishers of Mathias ��nard's Zone), and Claire-Louise Bennett's Pond), And Other Stories, 3AM Press, Dublin's Tramp Press and (in the US) Dalkey Archive and Coffee House Press.

But evangelical zeal and high-minded intentions aside, is there room for yet another literary prize? Griffiths has a brisk defence: "Whatever one thinks about awards in the arts, they do tend to attract attention, boost sales, and provide a little momentum ��� which is always a good thing. And even though the money won���t be Booker or Costa levels, any money is always welcome. And if the prize can include the independent bookshops ��� as judges and points of sale ��� then everyone wins".

That remains to be seen, but I think he's on to something. He has put ��2,000 of his own money into the prize, and more will probably be added. Speaking to the Guardian at the time of the launch, he said: ���I think I���m going to try and put a bit of a guilt trip on high-selling literary novelists, asking them to match what I���ve thrown in. I���m hoping to get it up to about ��10,000 . . . . These quite niche, quite difficult literary novels are really important in terms of making sure we have a vibrant literary life, so let���s support them���.

The nine judges announced last week are Griffiths, his co-chair Marcus Wright, and the booksellers Sam Fisher (Burley Fisher Books, London) Gary Perry (Foyles, London) Anna Dreda (Wenlock Books, Shropshire) Helen Stanton (Forum Books, Northumberland) Lyndsy Kirkman (Chapter One Books, Manchester), Emma Corfield (Book-ish, Crickhowell, Wales) and Gillian Robertson (Looking Glass Books, Fife, Scotland).

Speaking to The Bookseller recently, Griffiths said: "I realized after having a conversation at a literary event that half of these small publishers are vulnerable to going bankrupt half of the year. They don���t have big names such as Jamie Oliver or David Walliams to keep them afloat if their literary fiction either does or doesn���t work ��� but if they sell an extra 200 copies it can make a great difference. This is what I hope this prize will help to do. The business model is terrible so you would only do it if you love it".

Love? Yes, and why not? There's no reason our literary culture should be in entirely in thrall to marketing teams and focus groups and balance sheets and bottom lines. It's about much more than big advances and hype. It's about aiming high and taking risks, and having a stubborn belief in the enduring value of good writing.

April 8, 2016

Rediscovering Marie Duval

By MICHAEL CAINES

A ventriloquist's dummy was one of the more unusual exhibits on display in the Comics Unmasked exhibition at the British Library a couple of years ago. The dummy represented a character who owes something to Dickens's Mr Micawber (as the ODNB puts it): "bulb-nosed, bald-headed, spindle-shanked, bespatted big boots, batter-hatted, and of course booze-nosed . . .". Ally Sloper was a rent-dodging rogue (as his name suggests, slopes up an alley to avoid paying up) and, unusually among the other "nineteenth-century precursors to the twentieth-century industry" (I'm lazily quoting myself here) in the BL's exhibition, a comic character popular enough to escape the confines of the page.

Several cartoonists produced Sloper-centric series, which had originated in the pages of London's weekly "Serio-Comic Journal" Judy (established as a rougher-and-readier riposte to Punch) in 1867. By 1884 this rogue had grown sufficiently in popularity for him to have a weekly of his own: Ally Sloper's Half Holiday. Only one cartoonist, however, has just had an online archive of her work launched at the Guildhall Library . . . .

The emphasis on "her" is necessary because Marie Duval ��� the pen-name for Isabelle ��milie de Tessier, born in Islington in 1847 to French parents ��� was a "humorous designer", as one contemporary source calls her, in a field absurdly dominated by men. And as with so many pioneers, it can hardly be said that history has treated her fairly: her Sloper work was to be reprinted with her initials removed; the details of her life seem to have lapsed into obscurity (but see Ellen Clayton, the not entirely trustworthy source just mentioned, and this informative blog post by Marco Graziosi); and although she is credited in the ODNB as a "pioneering female cartoonist", she plays second fiddle there to her partner (in life as in art, it seems) Charles Henry Ross, who originated Sloper.

Ross himself made it clear in a letter to another journal that he did not regard her as an imitator of "Mr C.H. Ross���s absurd style". Her work "can very easily be distinguished from that gentleman���s production, because Mademoiselle is an artist and C.H.R. is not".

Also forgotten ��� or barely acknowledged at all beyond those who knew her work well ��� was that Duval did a lot more than sit around obediently inking Ross's Sloper sketches. As the creators of the Marie Duval Archive revealed at the launch last Thursday, Sloper represents only about 7 per cent of her known work. (And at the time of writing the site doesn't mention Ross at all.) She produced hundreds of illustrations for Judy between 1869 and 1885. The effect is often "humorous to grotesqueness", as Clayton says, a quality which seems to have been heightened by Duval's stage experience, as both a performer and an observer.

We were shown pictures of how an acrobat could dive through an upright piano, so that his legs appear above the keyboard while his head appears below it, alongside examples of her work that reflected this kind of spectacular flexibility. Duval's dancing, leaping, tumbling, stumbling figures certainly have a little more lifelike looseness to them than this consciously placid depiction of Matthew Arnold as a trapeze artist, in flight between "poetry" and "philosophy", by her contemporary Frederick Waddy; instead, there may be a debt to Punch cartoonists such as Richard Doyle (an edition of whose illustrated letters to his father will be reviewed in the TLS soon).

In English Female Artists, Ellen Clayton suggested that Duval had direct, dramatic experience of what chaos could ensure when stage action went wrong:

"Once, at Yarmouth, she met with a serious accident, which necessitated the performance being brought to an untimely end. In the piece in which she was acting ��� a version of Les Chevaliers du Brouillard, the French play of Jack Sheppard ��� she, as Jack, had to make a desperate escape, climbing up a rope ladder from a boat on to old London Bridge, under a volley of pistol shots from Jonathan Wild, the thief-taker, and his myrmidons. The cartridge from one of the pistols struck the actress on the side of the face, thus obliging her to loose her hold. She fell from the ladder, receiving a severe cut on the leg from a piece of iron used to strengthen the scenery. With a great effort she managed to climb the rope once more, and so brought the scene to a close, but the play had to end with this act. A doctor was sent for, who sewed up the wound, and no coach at that late hour being obtainable, a kind of sedan chair was improvised from the stage 'throne', and the disabled 'Jack' was carried to the Star Hotel through the streets at midnight by her old enemy Jonathan, and other members of the company. They said at the time that she bore the operation bravely ��� 'just like Jack would have done'."

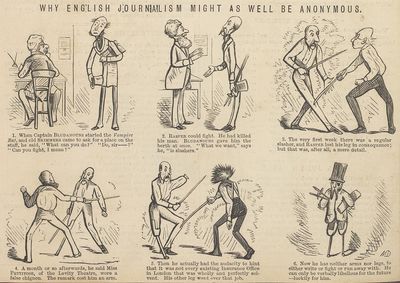

Duval's "theatrical" style anticipates later developments in cartooning, and can be seen in pieces such as "Another Blighted One", "The Luckless Love of a Loose-Legged Mariner" and the flailing legs in a corner of "The Latest Novelty: Rinking en salon". See also "The Stuffed Fish", "Something like a Lark!" and, for an explicitly theatrical jape, "The Shattered Idol". And much more ��� the Duval Archive makes for good browsing, and the standard of reproduction is much higher than for the Duval images to be found elsewhere. "Why English journalism might as well be anonymous", reproduced above, has a certain piquancy still.

April 5, 2016

Crime and Punishment

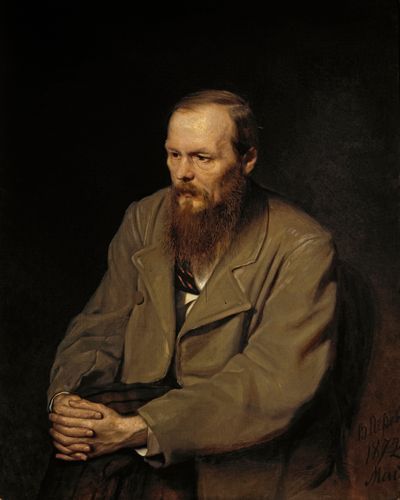

Fyodor Dostoevsky by Vasily Perov, 1872; State Tretyakov Gallery

By BRYAN KARETNYK

Sheltering from the evening drizzle on a grey Maundy Thursday in London, a crowd packed into the National Portrait Gallery���s Ondaatje Wing Theatre for a talk on Dostoevsky���s great novel of resurrection, Crime and Punishment. The latest in the gallery���s "In Conversation" series, the talk was part of a varied programme of events complementing a newly opened exhibition: Russia and the Arts: The age of Tolstoy and Tchaikovsky. The legacy of Dostoevsky���s novel, which was published a century and a half ago this year, was the subject for a panel composed of the literary specialists Oliver Ready (the TLS's Russia editor), Sarah Young and Lesley Chamberlain.

Ready, who is also the novel���s most recent translator, playfully opened the discussion by noting that the typical question of a classic work���s "relevance today" can often sound threatening, laying the onus on the novel to engage us rather than on us to engage with the novel. So Ready invited his co-panellists to look through the other end of the telescope and consider not what the novel can tell us about our world, but rather how similarities in our world might bring us to a closer understanding of Dostoevsky���s novel. Young painted a vivid picture of the St Petersburg to which Dostoevsky returned from his period of Siberian exile. The city he saw as he began work on Crime and Punishment was radically changed: there was overcrowding, a sudden influx of migrants, strange foreign ideologies floating around, and a surge in urban poverty and vice. The novel that he would go on to write ��� one that he intended to be "current", very much of the year of its composition ��� abounds, Chamberlain reminded us, in newspaper details and topical references. It was a book, Young surmised, written about "the world of today, but also fearful for the future".

The talk meandered through the philosophical quagmires of the novel (deftly outlined by Chamberlain) before considering Dostoevsky���s reception in the West. The fact that doom and gloom is so closely associated with the author ��� Marcel Proust claimed that Dostoevsky���s entire opus could be titled "Crime and Punishment" ��� is, it would seem, somewhat unfair. The panel commented on his brilliant flashes of humour, an oft-forgotten aspect of his writing. (Actually, Dostoevsky���s skill as a humorist was one of the few merits as a writer that Vladimir Nabokov, his most infamous critic, was willing to concede.) Comparing the author of Crime and Punishment to his erstwhile mentor Nikolai Gogol, Ready further remarked that while Gogol���s oeuvre succeeds in bringing out the tragic in comedy, Dostoevsky���s great skill is showing the comic in tragedy.

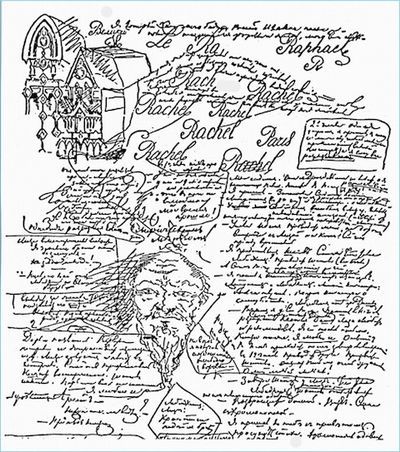

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Devils, manuscript

One of the most fascinating moments in the discussion was the brief but beguiling consideration of Dostoevsky���s manuscripts, with their doodles and illustrations. Here, as we were shown, may be seen the very texture of Dostoevsky���s writing in visual form ��� subplots sprouting in all directions around the main plot, adorned with the author���s calligraphy, sketches of high Gothic architecture, and haunting portraits.

Questions followed. The audience was keen to know whether Dostoevsky had any modern literary heirs. The three names touted by the panel were the recent Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich; winner of the Russian Booker Prize, Vladimir Sharov; and, the ostensible outsider in the group, J. M. Coetzee.

It is testimony to Dostoevsky���s enduring "relevance" that after 150 years his work should not only keep us talking, but also draw such a crowd. I now find myself unable to shake a nagging thought prompted by Ready's original question: in all those years, has the world really changed so little? As readers will note, those very "topical" concerns of 1865 seem disconcertingly familiar.

A series of lectures, workshops and live music events accompanies Russia and the Arts: The age of Tolstoy and Tchaikovsky, which runs at the National Portrait Gallery until June 26.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers