Rediscovering Marie Duval

By MICHAEL CAINES

A ventriloquist's dummy was one of the more unusual exhibits on display in the Comics Unmasked exhibition at the British Library a couple of years ago. The dummy represented a character who owes something to Dickens's Mr Micawber (as the ODNB puts it): "bulb-nosed, bald-headed, spindle-shanked, bespatted big boots, batter-hatted, and of course booze-nosed . . .". Ally Sloper was a rent-dodging rogue (as his name suggests, slopes up an alley to avoid paying up) and, unusually among the other "nineteenth-century precursors to the twentieth-century industry" (I'm lazily quoting myself here) in the BL's exhibition, a comic character popular enough to escape the confines of the page.

Several cartoonists produced Sloper-centric series, which had originated in the pages of London's weekly "Serio-Comic Journal" Judy (established as a rougher-and-readier riposte to Punch) in 1867. By 1884 this rogue had grown sufficiently in popularity for him to have a weekly of his own: Ally Sloper's Half Holiday. Only one cartoonist, however, has just had an online archive of her work launched at the Guildhall Library . . . .

The emphasis on "her" is necessary because Marie Duval ��� the pen-name for Isabelle ��milie de Tessier, born in Islington in 1847 to French parents ��� was a "humorous designer", as one contemporary source calls her, in a field absurdly dominated by men. And as with so many pioneers, it can hardly be said that history has treated her fairly: her Sloper work was to be reprinted with her initials removed; the details of her life seem to have lapsed into obscurity (but see Ellen Clayton, the not entirely trustworthy source just mentioned, and this informative blog post by Marco Graziosi); and although she is credited in the ODNB as a "pioneering female cartoonist", she plays second fiddle there to her partner (in life as in art, it seems) Charles Henry Ross, who originated Sloper.

Ross himself made it clear in a letter to another journal that he did not regard her as an imitator of "Mr C.H. Ross���s absurd style". Her work "can very easily be distinguished from that gentleman���s production, because Mademoiselle is an artist and C.H.R. is not".

Also forgotten ��� or barely acknowledged at all beyond those who knew her work well ��� was that Duval did a lot more than sit around obediently inking Ross's Sloper sketches. As the creators of the Marie Duval Archive revealed at the launch last Thursday, Sloper represents only about 7 per cent of her known work. (And at the time of writing the site doesn't mention Ross at all.) She produced hundreds of illustrations for Judy between 1869 and 1885. The effect is often "humorous to grotesqueness", as Clayton says, a quality which seems to have been heightened by Duval's stage experience, as both a performer and an observer.

We were shown pictures of how an acrobat could dive through an upright piano, so that his legs appear above the keyboard while his head appears below it, alongside examples of her work that reflected this kind of spectacular flexibility. Duval's dancing, leaping, tumbling, stumbling figures certainly have a little more lifelike looseness to them than this consciously placid depiction of Matthew Arnold as a trapeze artist, in flight between "poetry" and "philosophy", by her contemporary Frederick Waddy; instead, there may be a debt to Punch cartoonists such as Richard Doyle (an edition of whose illustrated letters to his father will be reviewed in the TLS soon).

In English Female Artists, Ellen Clayton suggested that Duval had direct, dramatic experience of what chaos could ensure when stage action went wrong:

"Once, at Yarmouth, she met with a serious accident, which necessitated the performance being brought to an untimely end. In the piece in which she was acting ��� a version of Les Chevaliers du Brouillard, the French play of Jack Sheppard ��� she, as Jack, had to make a desperate escape, climbing up a rope ladder from a boat on to old London Bridge, under a volley of pistol shots from Jonathan Wild, the thief-taker, and his myrmidons. The cartridge from one of the pistols struck the actress on the side of the face, thus obliging her to loose her hold. She fell from the ladder, receiving a severe cut on the leg from a piece of iron used to strengthen the scenery. With a great effort she managed to climb the rope once more, and so brought the scene to a close, but the play had to end with this act. A doctor was sent for, who sewed up the wound, and no coach at that late hour being obtainable, a kind of sedan chair was improvised from the stage 'throne', and the disabled 'Jack' was carried to the Star Hotel through the streets at midnight by her old enemy Jonathan, and other members of the company. They said at the time that she bore the operation bravely ��� 'just like Jack would have done'."

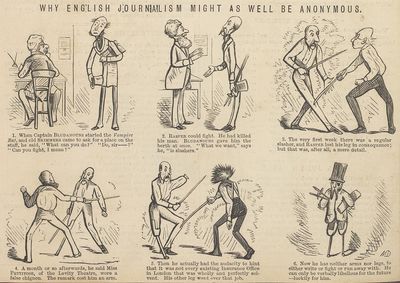

Duval's "theatrical" style anticipates later developments in cartooning, and can be seen in pieces such as "Another Blighted One", "The Luckless Love of a Loose-Legged Mariner" and the flailing legs in a corner of "The Latest Novelty: Rinking en salon". See also "The Stuffed Fish", "Something like a Lark!" and, for an explicitly theatrical jape, "The Shattered Idol". And much more ��� the Duval Archive makes for good browsing, and the standard of reproduction is much higher than for the Duval images to be found elsewhere. "Why English journalism might as well be anonymous", reproduced above, has a certain piquancy still.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers