Peter Stothard's Blog, page 12

February 22, 2016

The translation Oscars

Antonella da Messina's "Portrait of a Man" (1475), which graces the cover of Georges Perec's Portrait of a Man ��� Louvre/Peter Willi/Bridgeman Image

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

The community of literary translators had its own Oscars (or Baftas) last week. The Society of Authors brought together the winners and runners-up in several translation categories for an evening hosted (as it has been for the past three years) by Europe House in Central London. Annual prizes go for French translation (sponsored by the Institut Fran��ais), German (the Goethe-Institut) and Spanish (the Instituto Cervantes). Prizewinning translators from Arabic, meanwhile, have the Banipal Trust for Arab Literature to thank as well as the Ghobash family. The quartet were joined this year by translators from the Swedish (the Anglo-Swedish Literary Foundation) and Dutch (the Dutch Foundation for Literature). The Italian John Florio Prize returns next year. In past years there have also been prizes for translation from Greek, Hebrew and Portuguese.

Unlike at the Oscars, we don���t have an envelope-opening moment: the identities of the winners and runners-up are already known. The Egyptian novelist Youssef Rakha kicked off proceedings by reading a passage from his novel The Book of the Sultan���s Seal, followed by Paul Starkey, who read from his prizewinning translation from the Arabic. The Chair of the judges Robin Ostle described the judging process as an ���enriching experience��� while calling Rakha���s 374-page novel ���essentially untranslatable���; this made Starkey���s achievement all the more impressive.

In conveying apologies from her absent fellow French judge Andrew Hussey, Mich��le Roberts read Hussey���s commendation of David Bellos���s version of Portrait of a Man by Georges Perec: ���. . . Bellos is not only a match for Perec���s language but for the traps and snares of this ���lost text���, now restored, which provides the final piece in the Perec jigsaw puzzle for his English-speaking readers���. Bellos was runner-up to Frank Wynne for his version of Boualem Sansal���s Harraga. Wynne read in both French and English.

Emily Jeremiah spoke of the exceptional quality of the translations from German that she and her co-judge Benedict Schofield had encountered and Schofield read from the German of Jenny Erpenbeck���s The End of Days. Susan Bernofsky then read from her prizewinning translation.

Karin Altenberg, in the course of stressing the importance of translation from the Swedish, revealed that the (triennial) Bernard Shaw Prize was so called because Shaw, on receiving his Nobel Prize, handed the money to the Nobel Academy for them to spend as they saw fit. She then read a droll statement of thanks from the absent American translator of Tove Jansson���s The Listener, Thomas Teal (who also won in 2009 with an earlier Jansson title, Fair Play).

Anne McLean, Javier Cercas���s regular translator, was the winner of the Premio Valle Incl��n for her rendition of Outlaws. Jason Wilson, who judged the prize with John King, lamented the absence of Latin American work among the entries (all were from Spanish writers). Margaret Jull Costa, who seems to be an annual fixture, was runner-up this year with her version of Benito P��rez Gald��s���s Tristana.

The joint winner of the Vondel Prize, Donald Gardner, read resonantly from his translations of the Dutch poet Remco Campert, of which the judges, eloquently represented by the TLS contributor Paul Binding, wrote: ���Gardner���s translations show true empathy; . . . the authentic voice of the original Dutch poems rings through in the translation. This is a great achievement���. Gardner���s co-winner Laura Watkinson, the translator of The Letter for the King by Tonke Dragt, revealed that it had been a long-held ambition of hers to translate the novel (published in Holland in 1962). The prize vindicated her decision to do so, and she seemed particularly thrilled to have it.

I came away with a renewed sense of the sheer hard work that goes into the art, or craft, of translating. Not only are you dealing with someone else���s ideas and words rather than your own, but you must treat those words with the utmost respect. And all too often, reviewers only draw attention to a translation in order to criticize it, sometimes unfairly. That seems a shame: it could be argued that a successful literary translation is an achievement even greater than an Oscar-winning performance.

Red Africa

Installation by Onejoon Che; photo by Benoit Pailley, courtesy of New Museum, New York

By ANNA ASLANYAN

Senegalese, Ethiopian and Zimbabwean monuments, all similarly phallic and Soviet-looking, despite the surrounding palm trees; statues of African gentlemen, embodying the socialist-realist idea of a generic nineteenth-century liberal; a drawing captioned "Vladimiro M. [Mayakovsky] has landed in Havana and is talking to the black guy who is selling the red fish". These are among the images offered by Red Africa, a series of talks and screenings run by the foundation Calvert 22. Its aim is to explore the links between Africa, the USSR and "related countries".

At the centre of the series is an exhibition whose working title, Black Students in Red Russia (borrowed from a BBC Radio 4 feature) has been changed to Things Fall Apart (borrowed from Chinua Achebe, who in his turn borrowed it from W. B. Yeats). In a recent talk at the gallery, the curator Mark Nash and some of the participants touched on the programme's references to the African independence movements, the short-lived socialist "utopia" that followed them, and "the Cold War that wasn't cold". ���

The artist Isaac Julien said that the exhibition Re-imagining October, which he had co-curated for Calvert 22 in 2009, had left some "unfinished business" ��� the African theme. The same applies to various unfinished utopian projects as exemplified by Kiluanji Kia Henda's "Karl Marx, Luanda", a picture of a huge rusty hull of a ship run aground. Julien and the sculptor Angela Ferreira discussed the impact of Soviet thinking on African cinema and other forms of "subliminal Soviet influence" in the region.

���

Kiluanji Kia Henda, Karl Marx, Luanda, 2005; courtesy of Nomas Foundation, Rome

Even more tangible has been the North Korean presence in Africa. "Mansuade Master Class", a multimedia work by Onejoon Che, concerns monumental sculptures sent by Pyongyang to a number of African countries, often as gifts. Another country that sought allies among the newly independent states was Yugoslavia, a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). "Travelling Communiqu��", a project that includes materials related to the movement's first conference, held in Belgrade in 1961, is given ample space in the exhibition. One of the gallery's walls is taken up by texts and images documenting Yugoslavia's involvement in Asian-African affairs. A photograph on the wall opposite, picturing the heads of the non-aligned states in a dull official room, has a few Africans in it.

���Also on display are several works by Tonel, the Cuban artist, addressing another utopia, that of space exploration. One of these, a diagram captioned "The deadliest radioactive minerals found on the Moon by the Cuban-Soviet joint manned expedition of 1971 [partially translated]", sports some (misspelt) Russian words. Another imagines the Soviet cosmonaut Romanenko and his Cuban colleague Tamayo, the first person of African descent in space, under an upside-down house hanging from a cratered surface. Talking at the event, Tonel described his work as mixing history and sci-fi. ���

Angola, Yugoslavia, Mozambique, Cuba, North Korea, the USSR: does the list reflect diversity or a colonial tendency not to differentiate too sharply between distant dominions? One thing it brings to mind is a sketch by Vladimir Voinovich, in which a Soviet engineer keeps confusing Angola with Anglia. A collage in which Yevgeniy Fiks shuffles images from the Wayland Rudd Collection ��� Soviet posters, stamps and cartoons featuring black people ��� demonstrates that the early Soviet view of the Other was similarly vague. For all the variety of "related countries" on display, the exhibited art is surprisingly uniform. "Why are there no revolutionary artists?" asked one of the audience at the end. Mayakovsky would have demanded the same.

Red Africa runs until April 3 at Calvert 22 Foundation, 22 Calvert Avenue, London, E2 7JP.

February 18, 2016

Sylvia Plath: what price a kiss?

By JIM McCUE

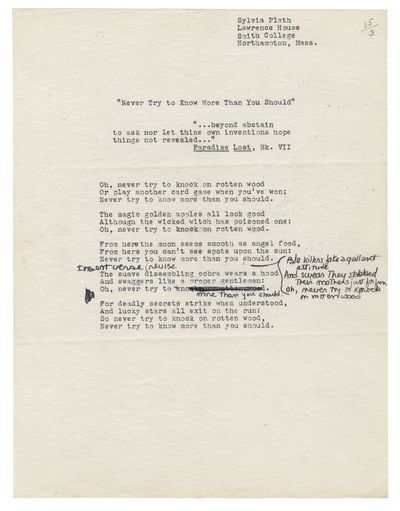

Manuscripts of sixteen early poems by Sylvia Plath will be auctioned at Bonhams on March 16, along with photographs of her, and a birthday-card-letter to her mother from 1953, in which a rapturous Plath describes meeting W. H. Auden. Some of the material was first seen on the market when sold by the Plath estate in New York in 1982; more is anticipated, as a large collection is broken up.

The nine drafts in one lot date from Plath���s early teens, when, according to Ted Hughes, her poems were ���always inspired high jinks, but frequently quite a bit more���. A second lot is made up of typescripts of six poems from her time at Smith College, including one beginning ���All day she plays at chess with the bones of the world���. Two typed and autograph drafts of ���Never Try to Know More Than You Should��� (published in the Collected Poems as ���Admonitions���) comprise a third lot.

Each of these lots has an estimate of ��1,500���2,000, whereas a small group of ���autograph drafts, notes, drawings and doodles for her story ���Stardust��� . . . (with three red lipstick kisses applied by the author)��� is estimated at ��4,000���6,000. What price a kiss from Sylvia Plath?

February 17, 2016

Shirley Brooks and the ashes

By JIM McCUE

Although the occasion is unlikely to be much remarked, 2016 will see the 200th anniversary of the birth of Punch's third Editor, Shirley Brooks.

Resourceful and witty, he wrote for many papers, reported from Russia, Syria and Egypt, and took Dickens���s former place as parliamentary correspondent of the Morning Chronicle. He also wrote plays which were staged in the West End with moderate success. His column in the Illustrated London News was engagingly entitled ���Nothing in the Papers���, and he had a novel illustrated by Tenniel. On February 24, Catherine Southon Auctioneers will sell a stray volume of his diary (estimate ��600���800), which includes an elegy for a young sweetheart whom he had never quite had the courage to kiss.

Along with Anthony Trollope, Brooks was among the founder members of the Cremation Society of England, but when he died in February 1874, just a month after its inaugural meeting, the practice was still illegal, so he had to be buried. The irony of this may have led, thanks to his son, the "fl��neur" Reginald Shirley Brooks, to the naming of one of our greatest sporting contests, The Ashes.

In March 1882, a Miss Eliza Williams was granted permission by the Home Secretary to exhume her friend Henry Crookenden, though specifically not to fulfil his wish to be cremated. Nevertheless, according to a long legal report in The Times, after digging him up, she ���caused the body to be cremated at Milan, and the ashes to be returned to England���, where they were put in a vase from his collection and buried. When she then sued his estate for ��321 expenses, her case was dismissed.

Given the thwarting of his own father���s wishes, Brooks junior very probably took an interest in this bizarre case, and had it in mind that summer when, for the first time ever, the England cricket team lost a Test Match to Australia. As journalist himself, he is believed to have been the wit who wrote the facetious death notice in The Sporting Times declaring that English cricket had died at the Oval and that ���The body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia���.

Cremation was ruled legal two years later by the judge Sir James Fitzjames Stephen. Neither the mortal nor the literary remains of Shirley Brooks, however, have been exhumed.

February 15, 2016

The End of Longing

Photo By Helen Maybanks

By ANDREW IRWIN

A new playwright is staging his debut work, the grandly titled The End of Longing, in the West End. The writer also stars in the play and dominates the publicity poster, which is plastered across the London Underground. The level of attention is justified, however ��� at least on a commercial level. For this new writer is none other than Chandler Bing. Matthew Perry���s play, which is running at the Playhouse Theatre by Embankment, tells the story of four Americans struggling to find conventional stability and contentment as they approach middle age ��� one is an alcoholic (played by Perry, who has himself been treated for addiction); one is a high-end prostitute; one is a neurotic; and one doesn't really have a thing, apart from apparently being ���stupid��� (which leads to some very shallow characterization, but quite a funny opening line). His name is Joseph: we are left to wonder whether his surname is Tribbiani.

The programme tells us that this is ���about the ���Friends generation������. A comparison to Friends is something of a hostage to fortune ��� it was a fairly successful sitcom in its time ��� and one wonders if making it is a wise move; it seems as if Perry is being drawn back to the 1990s, defined by a show that ended twelve years ago. That said, for many (including me), the sitcom still inspires great affection ��� and it is hard not to feel positively disposed towards anything Perry produces. As the performance began ��� with some intro music that rather resembled the sitcom���s segues ��� I was willing to believe it was going to be great. Sadly, it was not.

We are introduced to the four leads when each one takes the spotlight in turn and delivers a brief monologue, laying bare the character traits that will both define them and drive the plot. The scene then shifts to a bar, where the two women, Stephanie and Stevie ��� best friends ��� are chatting, while Perry���s character, Jack, smokes in the corner and downs double-Stoli after double-Stoli as he waits for his friend, Joseph. The women converse: Stevie mentions a recent date who hasn���t yet texted back, and Stephanie discusses her career as an escort to wealthy men. Overhearing them, Jack walks over and introduces himself with a slurry, clunking kind of charm. Joseph arrives shortly after and ��� in a twist of fate best-suited to sitcoms (I can imagine it working wonderfully in Frasier) ��� we discover that he is the very man Stevie has been seeing (���what are the odds?���, asks Perry).

The quartet become ever drunker as the night goes on. And in the next scene we learn that Jack (alcoholic) and Stephanie (prostitute) have slept together, and so too have Stevie (neurotic) and Joseph (stupid). Naturally, the pairs become couples. Soon Stevie discovers that she is pregnant ��� and, in a tension-free resolution, they both decide that this is a good thing. Jack and Stephanie���s relationship develops into something happy and mutually non-judgemental. But then there is a set piece in which Jack embarrasses himself in a bar, for some reason infuriating his three companions to the point of crisis: there are ultimatums, streams of expletives and breathless accusations (���Jack . . . we need to talk about your drinking!���). The second half of the play is set in a maternity ward, and works better, with more tension and a more natural plot development ��� even if there is the occasional shuddering zig-zag from comedy to melodrama.

Photo By Helen Maybanks

There is an uncomfortable moralizing involved in the whole thing ��� and a simplicity that seems to arise more from the need for clean plot resolutions than a desire to reflect the world. Having a baby will solve your problems, it seems. Being a prostitute is wrong ��� even when the subject concerned is genuinely untroubled by it. Redemption can be found in the love of a good woman.

The staging is striking, however ��� simple, atmospheric and faintly industrial ��� and the acting is solid. Perry���s own performance is a little uneven (especially in the more emotional scenes) but when the fast-talking back and forth begins, he returns to his old form, and reminds us how talented a comic actor he is. Happily, the jokes frequently land, and there is a decent amount of visual humour (a cocktail shaker in a sports bag works nicely). It would be good to see Matthew Perry more in the West End, playing the morosely comic roles at which he can excel ��� but I���m not convinced he should be writing them.

February 13, 2016

Farewell to the circumflex?

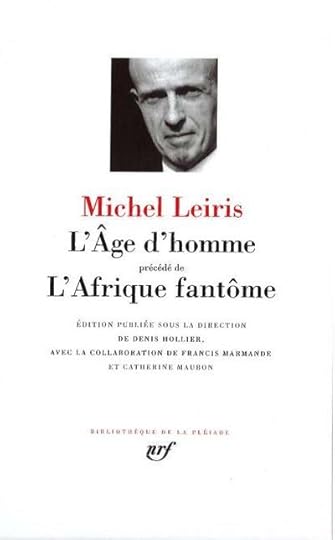

The cover of a book I recently sent out for a TLS review. Will the two circumflexes in the titles one day become a thing of the past?

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Ah, the circumflex! The French one that is, as opposed to the Portuguese (apologies for returning to orthographical matters so soon). And I realize that I���m a bit of a johnny-come-lately on this, having spent a week reflecting deeply on the changes to French spelling announced by the Conseil sup��rieur de la langue fran��aise (a government-regulated body). Some 2,400 words will be affected, and both the "i" and the "u" will drop their circumflexes. As has been widely reported, ���ognon��� will now rub up alongside ���oignon���, and ���n��nufar��� will do the same to ���n��nuphar���. (The changes will be optional, so both versions will be correct, but I can���t help feeling that ���ognon��� looks ugly without its ���i���, and that the ���ph��� is preferable too.) ���Ma��tresse��� is allowed to drop its circumflex, as is ���co��t��� (the circumflex generally denotes a suppressed ���s���, as in ���maistre��� or ���fenestre���). Some changes are less conspicuous: who's going to object to the French removing the eccentric hyphen from ���week-end���? Or to ���porte-monnaie��� and ���porte-feuille��� becoming ���portemonnaie��� and ���portefeuille���?

In France, news outlets reacted excitedly: ���La mort de l���accent circonflexe��� (Le Point); elsewhere we had ���Adieu circonflexe���. It was left to Le Monde to insist ���Non, l���accent circonflexe ne va pas dispara��tre��� (and there it is, on ���disparaitre���, as if to prove it).

The student union, meanwhile, lambasted the Minister for Education Najat Vallaud-Belkacem for appearing to give herself the right to overturn French spelling rules. She, and her department, did no such thing. It���s not in her gift. Rather, the publishers of school textbooks have decided to introduce simplified spellings in time for the new academic year in September. But students and pupils will not be penalized for spelling words in the old way.

Last week, the Acad��mie fran��aise, guardian of the French language, put out a statement on its website reminding us that it���s not responsible for the ���orthographical reform��� that���s been discussed in the press, referring readers to a document published by the Conseil sup��rieur de la langue fran��aise as long ago as 1990. The statement on the website goes on: ���Given the Acad��mie���s assigned role of defending and illustrating the French language, . . . it was natural that Maurice Druon, its permanent secretary at the time, should have been closely associated with the preparation of this report���.

The Acad��mie objects to the use of the term ���reform��� to refer to the changes proposed by the Conseil and which it has itself approved; these are, rather, ���rectifications���. The 2,400 words apparently amount to 3 to 4 per cent of the French lexicon ��� which sounds like quite a lot to me.

A bit of context here: we���re told that these adjustments correspond to those the Acad��mie made when it published the third edition of its Dictionary (1740), the sixth (1835), the seventh (1878) and the eighth (1935). The ninth is still in preparation. The Acad��mie stresses that it merely recommends changes, and it has approved the course of accepting both the old orthography and the modernized one proposed by the Conseil. Hence in the ninth edition of its Dictionary, it will use the traditional orthography while also mentioning the acceptable variant.

The best response to the news came from the writer Pierre Assouline on his excellent blog La R��publique des livres. While ridiculing some of the more hysterical reactions, he points out that the twin-track spelling system could have an effect opposite to the intended one, in that rather than helping to foster a more egalitarian educational system it could create new hierarchies based on superior spelling and orthography. He also wonders in jest whether the legends that accompany Monet���s paintings of waterlilies will have to be modified (i.e. ���n��nuphars" be changed to ���n��nufars���).

Personally, I���ve always liked the circumflex, and would be sorry to see its gradual disappearance. It���s one of the distinctive markers of the French language after all. But then I don���t have to teach it.

February 12, 2016

As You Like It

Paul Chahidi in As You Like It; photo by Johan Persson

By SAM GRAYDON

I recently went to see Polly Findlay���s much-acclaimed version of As You Like It at the National Theatre. On stage as we took our seats were garishly coloured carpeting, desks, chairs and pot plants: every scene of Act One was set in an office. We were perhaps to conclude that City workers were modern society���s aristocracy, but overall this staging added little to the play ��� in some places it was even detrimental. The wrestling scene (featuring heavy metal and a neon blue lucha libre outfit) was not just inconsistent with the office furniture but also physically constrained by it. That said, as the action moved to the Forest of Arden, the tables and chairs played a crucial part in a very impressive set-change.

In fact, it was so impressive it didn���t work. The performance was stopped for ten minutes so that a technical problem could be dealt with.

It may be unfair of me to pick up on this quirk of the evening (especially as the change of scene really was extraordinary to watch), but I do so because as people in hard hats filed out to deal with one of Arden���s immense trees, my friend (who had never seen Shakespeare in the theatre before) turned to me and asked: ���Now this definitely isn���t in the play, is it?��� And I could hear quite a few mutterings of a similar nature around me. It seemed that many in the audience would have patiently sat through the impromptu construction work as an interesting adaptation.

In an earlier TLS blogpost, Michael Caines compared the Rose Playhouse���s recent production of The Devil Is an Ass with the NT���s As You Like It, and guessed that ���the set alone for Shakespeare's comedy cost more than [the] entire budget for Jonson���s���. But I would add that a big budget can sometimes distract us from what makes a play great, and can lead us to expect and excuse gimmicky additions to an otherwise perfectly good performance. The elaborate effects and the enjoyable dance and songs did make As You Like It a lively spectacle, but it was not this that made the performance such a good one.

The acting was excellent ��� Rosalie Craig���s Rosalind was commanding and charismatic, and Paul Chahidi expertly captured the mixture of laughable and pitiable offered by Jacques. Considering that Findlay likened the play to a ���1599 version of The Fast Show���, it was impressive that she made the disparate plot-threads clear throughout. There were moments of sketch-like farce ��� the cast crawling around in white Aran-knit jumpers pretending to be Corin���s flock of sheep, for example ��� but such moments fitted in easily with the play���s profound reflections on time and love. My friend and I agreed that it was the acting and direction, much more than the showmanship, that made Findlay���s production so enjoyable.

In the hubbub of opinion that followed the performance I overheard an exchange that summarized the various conversations of the exiting audience beautifully: ���Well that was a lot of faffing about wasn���t it?��� ���Yes. But I liked it���.

Joe Bannister and Leon Annor in As You Like It; photo by Johan Persson

February 11, 2016

Designer bodies

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

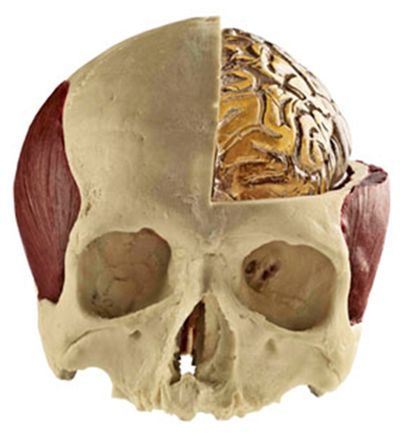

Drilling into a human skull and operating on a brain requires, I hope, a lot of training. But how do neurosurgeons practise, or even experiment? I ducked into a fascinating exhibition at the Hunterian Museum on Lincoln���s Inn Fields recently which shows how 3-D models of human anatomy are meticulously made for this very purpose. For trainee surgeons hands-on interaction, as well as theory, is crucial.

It seems simple enough to build a scale model of a head ��� what���s not simple is getting it to feel like one. The focus of Designing Bodies (running until February 20) is on the MARTYN (Modelled Anatomical Replica for Training Young Neurosurgeons; picture above), developed over the past four years by a surgeon and an artist, with the help of the Hunterian (which is part of the Royal College of Surgeons). Despite the sterile, gleaming display cabinets, the MARTYN looks like an almost primitive artwork: it���s split into five main components, one being the skull which is cast in polyurethane resin. On display, though, the mould from which the skull is cast is like any other found in a sculptor���s studio ��� bits of wood screwed together around clay or silicone (the use of digital technology now, i.e. 3-D printing, only means that the mould is built more accurately more quickly from a print-out, rather than by hand). Muscle components are made from silicone; the brain from a special gelatin mixture. Then we come across ventricles, the fluid-filled cavities within the brain (sliced in two here, they appear buttery, cloying; the right texture); and finally the dura mater, a membrane which surrounds the brain, recreated from latex.

Other simulated ���features��� created for the MARTYN include tumours and drainable fluid from the brain. A photograph, taken last year at Imperial College, presents a robot performing keyhole surgery on a MARTYN ���featuring a model aneurysm in the circle of Willis���. (Is it just me, or is some of the gallery���s wording darkly comic?)

Not only are materials tested ��� with scientific precision, of course ��� for their likeness of feel to the real thing (a cabinet is devoted to a few of those that didn���t work: casting the ventricles in ice seems an obvious error to me, not least in terms of durability; for the dura mater, rice paper turned out to be ���ideal when wet but too crisp when dry���), they need to look right, too. Different shades of red dye ��� used to mimic blood clots ��� are tried out, for example, on circular swatches.

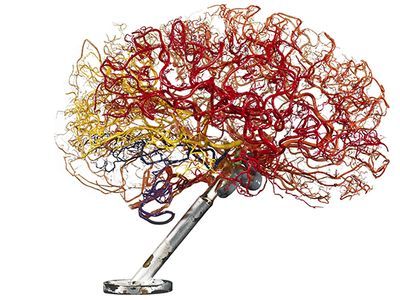

Cast model of a brain by David Hugh Tompsett �� Royal College of Surgeons. Photograph by Michael Frank

Cast model of a brain by David Hugh Tompsett �� Royal College of Surgeons. Photograph by Michael Frank

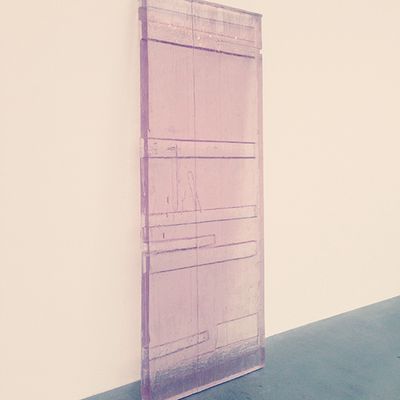

Going back fifty or so years, the exhibition turns to a Royal College anatomist David Hugh Tompsett, who pushed the boundaries of ���corrosion casting���. Injecting a new type of liquid resin into prepared dead organs and body parts, Tompsett would then dissolve away any remaining tissue with hydrochloric acid to reveal the intricate paths the resin had filled ��� blood vessels and airflows. He would prune and sculpt his corrosion casts like a bonsai tree with metal tools to highlight different areas for surgeons to look at. A delicate cream, alien-looking bronchial tree from the 1950s sits alongside more elaborate multi-coloured corrosion casts of heart and brain vessels. I wonder if the sculptors Helen Chadwick, with her ���Piss Flowers��� (casts of urine in snow), or Rachel Whiteread (who fills the insides of everyday objects ��� doors, boxes, sheds, houses ��� in resin) ever saw Tompsett���s models.

A door by Rachel Whiteread at the Gagosian Gallery, London, 2013. Photograph �� Mika Ross-Southall

A door by Rachel Whiteread at the Gagosian Gallery, London, 2013. Photograph �� Mika Ross-Southall

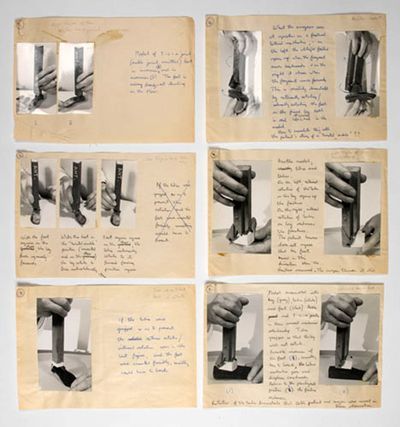

Over in another corner of the gallery, we find the orthopaedic surgeon John Herbert Hicks���s wooden ���joint��� models ��� of knees, ankles and so on, during the 1950s and 60s. He recorded how his models moved in a black-and-white photoseries, similar to Eadweard Muybridge���s photographs of motion. ���It is difficult to visualize but the model will help���, Hicks told his students in 1955. ���To overcome the difficulties of a description confined to the two dimensions of this page the reader if he wishes to be convinced of the essential simplicity of all this must make for himself the cardboard model illustrated.��� And, sure enough, the Hunterian provides a piece of cardboard, with perforated push-out sections, for us to take away and make our own 3-D ankle-joint model at home, just like Hicks���s. Surprisingly challenging (at least for this visitor).

John Herbert Hicks���s photographs of his wooden joint models �� Royal College of Surgeons. Photograph by Michael Frank

John Herbert Hicks���s photographs of his wooden joint models �� Royal College of Surgeons. Photograph by Michael Frank

John Herbert Hicks���s ankle-joint model

John Herbert Hicks���s ankle-joint model

February 10, 2016

Whose London is it anyway?

From "This is Private Property", credit: Helen Murray

By MARINA GERNER

Tucked away between office buildings by Euston station is where I found the Camden People���s Theatre. It���s a little place with colourful bunting, a cheerful selection of chairs and flowery plastic tablecloths. It���s the kind of theatre where you can buy a packet of crisps in the interval, rather than wasabi peas.

I went to see a talk and two plays that were part of Whose London is it anyway?. The theatre was packed with people, young and old, who came to see a festival dedicated to London���s housing crisis. Instead of tickets, we received playing cards.

At the talk entitled ���Bland reform: Losing London���s subcultures���, panellists lamented the gentrification of London. The journalist and former sex worker Frankie Mullin spoke about the destruction of the ���coral reef��� of cultures in Soho, which took hundreds of years to grow. Queer spaces have been closed down. Artists can���t afford the rent. While sex workers have been pushed to work in places that are far less safe, developers capitalize on the area���s seedy reputation. Now ���there���s a bar with a red light outside and cocktails named after famous prostitutes���.

"What���s happened to Soho?��� has been a question for years, and it remains a pressing one. In 2014, a group of artists including Benedict Cumberbatch and Stephen Fry wrote a letter decrying the closure of the infamous nightclub Madame Jojo���s. In the same year, London���s street dance community lost its most important training ground in the Trocadero. Meanwhile, more and more street art is removed from the street to be put into museums. From Brixton to Hampstead, high streets are becoming indistinguishable ��� a desert of cultural sameness.

I was glad to hear another panellist, Mary-Ann Lewis, Euston���s Programme Manager at Camden Council, say that Westminster has special policies to protect the character of certain areas. She mentioned Savile Row, which is protected for its ���special skill���, and a cluster of antique shops in Mayfair. But in policy planning, ���character��� seems to extend only to those who can afford to lobby for themselves.

A cabaret artist called Scottee talked about the closing down of council housing in the Camden borough, where a property developer, Christian Candy (whose children are called Cayman and Monaco), is converting seven listed buildings by Regents Park into a mega-mansion. Scottee lamented the displacement of working-class communities from central London. The theatre employees themselves currently face eviction from the council apartments above the theatre premises.

The highlight of the evening was an extraordinary performance called ���Cuncrete��� written by Rachael Clerke. The central character was Archibald Tactful, a middle-aged architect, dressed in a grey suit and a grey shirt, who was also the lead singer of a band called The Great White Males. The other band members included a property developer on the drums, a banker and a cabinet minister without trousers on the bass.

���Right to buy ��� nothing���s left to buy���, they sang. Interspersed was David Cameron���s voice intoning: ���I want everyone to have their own home���. They sang about their achievements: ���we split the atom ��� you take it for granted; we beat the Germans, we fucked the natives. The economy? One of ours���, and their vision for society: ���art for everyone ��� on the Southbank���, while mixing concrete with champagne.

���We���re not archetypes, we���re as real as you are���, they said. It took some time for us to realize that all of the four band members were women dressed as men. Unlike drag queens with their hyper-feminine moves, this band of drag kings moved with a masculinity that felt natural, even though the characters they were playing were grotesque.

The final show of the evening ���This is private property���, told the story of Ruth, a single mother, who is decanted from her council flat. She and her baby son go on to live in a homeless hostel, where she is forced to collect points (for such issues as hardship and mental illness) to qualify for a new place in council housing. In surprisingly humorous ways, the play explored how London���s property became bitcoin for the rich. 61 per cent of new-builds are bought as an investment. There are 80,000 empty homes in London. 85 per cent of homes sold in central London are sold to foreigners. ���Dubai, Shanghai and goodbye���, they sang on stage.

At the end of the play, one character solved the housing crisis in thirty seconds, by suggesting rent controls, a ban on foreign ownership of London properties or at the very least a high enforceable tax on that ownership, and a land value tax to confront land-banking ��� the making of money by hoarding valuable land that has been earmarked for home-building. Another one suggested: ���We let the housing crisis run its course. What do these people ��� the politicians, the developers, the super-rich ��� what do they actually want for London? Clear out all the poor people and anyone who can���t afford million-pound homes. They are going to wake up one day and wonder where���s all the fun gone, where���s the variety?���.

Cities in which talent and ideas thrive tend to be characterized by a melange of cultures, classes and ethnic groups. In The Geography of Genius, Eric Weiner explored the golden ages of cities such as ancient Athens, Renaissance Florence and Silicon Valley. Their downfall, he wrote, came with creeping vanity, when ���bling has reared its shiny head���. London, I fear for you.

February 8, 2016

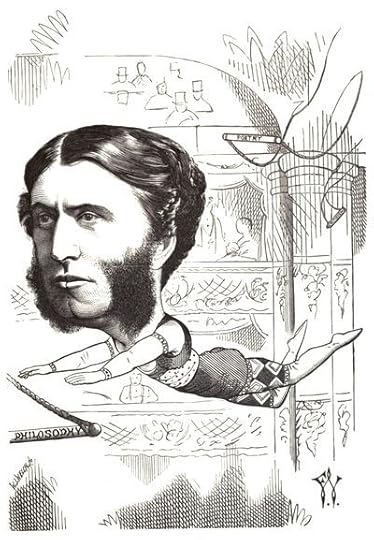

Matthew Arnold (and other Victorian big heads)

I picked up the review of copy of Introducing Literary Criticism: A graphic guide the other day ��� it's a neat volume published this month in a series of such introductions, a chronologically arranged primer in major critics and their views by Owen Holland. The cover tells you that the illustrations are by, simply, Piero. There are plenty of uncredited images in there, too, however, sometimes just adopted as background and presumably all out of copyright. About a third of the way through, the Piero cartoon version of Matthew Arnold, reproduced above, rang a bell. And when I turned the page, I saw why . . . .

There is plenty in Holland's text about Arnold's intellectual balancing act ��� his proposing of culture, whatever that is, as society's substitute for religion ��� but no mention of trapezes. Instead, I suppose, here is a case of one caricaturist inspiring another. For here is Arnold as one of his contemporaries saw him, in that illustration that appears over the page in Introducing Literary Criticism, more suitably attired for the Big Top:

How placid Arnold looks here, compared to Piero's quill-wielder . . . .

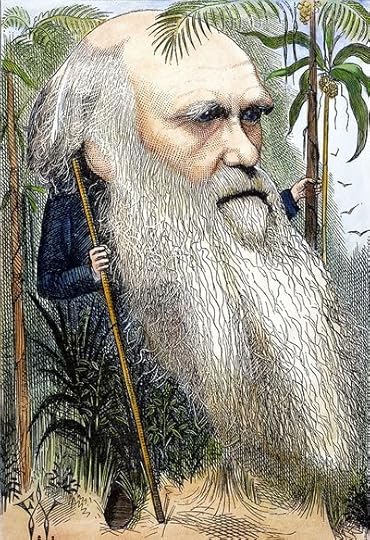

That elaborate "F. W.", in the bottom-right corner, refers to Frederick Waddy, an illustrator who is, I suspect, all too obscure given the ticklish quality of his work. Here's his Darwin, for example, which has certainly been wheeled out more often than his Arnold. It was captioned "Natural Selection" when it was first published in the innovatively illustrated journal Once a Week:

The Granger Collection, NYC/TopFoto

As suggested by the authors of The Smiling Muse: Victoriana in the comic press, "the accentuated beard and the enlarged head with deep-set eyes suggest a touch of 'aping' the famous scientst"; yet they see this as a "clearly complimentary" view.

It is no surprise that Waddy receives no credit in Introducing Literary Criticism; nobody else does. In fact, though, he doesn't seem to be widely recognized at all, and the details of his life are unknown, I guess, except among those who maunder after such minutiae in the relevant bookshops and research libraries. The often pleasantly distracting Public Domain Review didn't even pay him the courtesy of spelling his name right, although it's understandably amused by his series of Victorian big heads ��� comic exaggerations that suggest character rather than egotism.

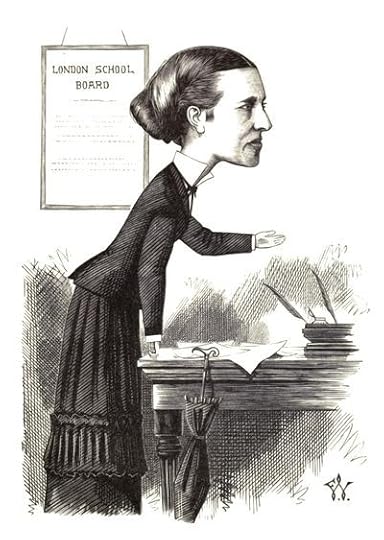

Without resorting to any desperate archival measures, all I've found about him since coming across his work in Cartoon Portraits and Biographical Sketches of Men of the Day (1873) derives from scattered references in one book or another: that he was born in 1848; that he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1878; that he married Edith Walford, the daughter of the prolific writer Edward Walford (I glean this from the ODNB in which Waddy, understandably, has no reference of his own); that his work appeared in Once a Week (for which he wrote the biographical sketches, too, a couple of secondary sources suggest) and the Illustrated London News; that you can find his work here (in Grammar-land) and there (helping to solve The Puzzle of Life); and that he is perhaps the Frederick Waddy "late of St Albans" (according to a notice in The Times) who died at Brighton on September 30, 1901. I'm probably missing an obvious source, but basically: any further information gratefully received.

The only woman, incidentally, to feature among these "men of the day" in Once a Week was the great medical pioneer and feminist Dr Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who is depicted here laying down the law:

Although I also have a soft spot for the caped Tennyson on his swing of poetic fancy, flying the banner of popularity, in motion like Arnold:

The Granger Collection, NYC/TopFoto

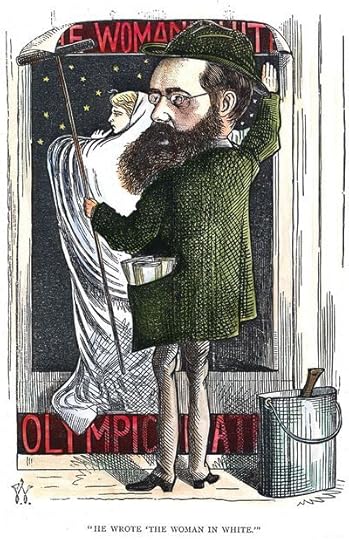

And for a publicity-seeking Wilkie Collins looking over his shoulder:

The Granger Collection, NYC/TopFoto

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers