Peter Stothard's Blog, page 14

January 14, 2016

Rhodes to ruin (and tea at the Midland)

By MICHAEL CAINES

There is a delirious moment in Simon Critchley's ABC of Impossibility when somebody asks him a question. It is not the question itself that disturbs him (or disturbs Critchley's alter ego at least, in this "experimental text of para-philosophical fragments working toward a poetic ontology"), but the name of the questioner:

From Simon Critchley's ABC of Impossibility. pic.twitter.com/OrdkpFhbXX

��� Michael Caines (@michaelscaines) October 27, 2015

Oddly, this neat little nightmare came to mind as I read about the ongoing debate concerning the Cecil Rhodes statue that both adorns and debases the fa��ade of Oriel College, Oxford ��� it's a mental association I couldn't wholeheartedly trust. For the ponderous question, read the statue; for the name and the oppressive history to which the name is a clue, read "Cecil Rhodes" and the whole of the British imperial project ��� no, it doesn't quite work, does it . . . .

My fellow editor Mary Beard has already blogged about the Rhodes controversy, so I won't repeat the arguments and counter-arguments here. Having rather poorly played the association game myself, though, I started to take more notice of how combatants on both sides of the debate resorted to the same kind of debate by analogy ��� some of them more effectively than others.

Howard Jacobson, for example, in a pro-statue piece in the Independent, points up at Nelson's Column, and mockingly copies the language of the censorious: "how much longer must we tolerate that vainglorious adulterer Nelson on his phallic column"? On the anti-statue side, meanwhile, Bidisha in the Guardian talks about a Quaker school in Philadelphia taking The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn off the syllabus "because of its heavy dosage of the N-word, which made students feel uncomfortable": "I���m wondering if the students were mainly white and their discomfiture was from having to confront the history (and present) of white racism as embodied in that word, or if it goes deeper than that and the racist stereotyping of Jim as emotionally naive, sentimental and simple was what stuck in their throat, as it does in mine".

For her part, thinking about the Rhodes statue meant Mary "couldn't help thinking about" what David Mitchell had said about Robert Gordon University stripping Donald Trump of his honorary PhD in peace studies (here comes an analogy within a supposedly analogous case):

"I think if it turns out you���ve made, say, Hitler an honorary PhD in peace studies, the record ought to stand as a rebuke to your whole honorary doctorate admissions policy. Otherwise it���s like a denial of historical fact: the truth is that, in 2010, Robert Gordon University thought Donald Trump was the bee���s knees and they shouldn���t get to erase that from their annals now it turns out he���s a prick."

Right or wrong, here's how I might respond:

I'm not sure I can agree wholeheartedly with David Mitchell's line of thinking. Even if he never changes his mind, other people, including university administrators, might wish to. And stripping somebody of a degree is not the same as erasing something from the annals is not the same as taking down a statue is not the same as taking Huck Finn off the reading list is not the same as ���

You get the idea. And yet rhetorically it seems there's no dispensing with likening this to that in the hope of being more persuasive (or, when preaching to the converted, as most media orators do, simply pushing the right buttons). Stripping Trump of that degree put me in mind of the stripping Lance Armstrong of his Tour de France medals, even though I know full well that they're very different cases (unless Trump's been caught doping while wearing the maillot jaune). The word association game continues.

Enough meta-journalism. Here's another little nightmare, but a sadder, more richly described one, courtesy of a writer whose work I'm reviewing for the TLS at the moment: David Constantine.

The film 45 Years, which has just been nominated for three Evening Standard Film Awards, including Best Film, is based on a Constantine short story; he published The Life-Writer, his second novel, last year (the first was published in the 1980s); and a selection of his stories has appeared, to complement both. It's from that selection, In Another Country, that I take this short story, "Tea at the Midland".

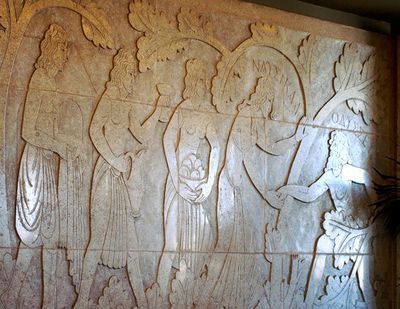

As you'll hear if you listen to the story, the frieze reproduced below is part of the story, being a contribution to the Midland Hotel at Morecambe Bay, on the Lancastrian coast, by one of the most dubious of modern artistic figures, Eric Gill. The story records an argument that arises out of the particular ��� ���if Gill were alive today", Simon Loxley has written of him, "we would be seeing him on the evening news, a coat thrown over his head, being bundled into a white security van��� ��� to reach for more general questions about a given piece of art and what we think of its maker, the person it represents, or the person we otherwise, for some reason, associate with it.

There are numberless variations on this theme, as the Rhodes statue debates imply. By offering tantalizing connections of its own, David Constantine's story seems admirably to make a virtue out of them.

January 11, 2016

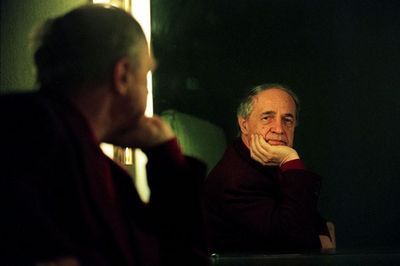

David Bowie ��� that particular circular mix

Photo by Barry Schultz / Sunshine / REX / Shutterstock

By ROZ DINEEN

Of all the artists to have been written about in the TLS David Bowie, who died on Sunday evening, is surely among the most vibrant and unpredictable; occupying that fertile artistic ground where vulnerability and certainty of vision combine.

���Through it all���, Wesley Stace wrote in the TLS in 2011, ���Bowie has remained an excellent and adventurous songwriter, something that often goes unmentioned. In his early years, not everyone fell for the guitar-strumming folkie singing Jacques Brel songs in funny clothes, but, as Bowie found his voice, and his lyrics, that particular circular mix of decadence and pending apocalypse, an apocalypse that seemed to excuse and demand further decadence (because if the world is doomed, we might as well have a party), his songs became ever more clearly the work of a master singer-songwriter. And even though the masks allowed Bowie a certain aloofness from the grimy world of rock, as he fashioned himself into the multi-media artist he had always claimed to be, he compared his songs to ���talking to a psychoanalyst. My act is my couch���. The further he strays away from this ruthless self-analysis, however opaque the images, the less successful his work and it is at those moments, when inspiration is lacking, that he has sometimes chosen to disguise the fact with noise.���

���Like all great stars���, Pat Kane observed in 1997, ���Bowie has been a showman of his selves; and where the empty core behind the display has driven contemporaries to either madness or blandness, Bowie has used his fractured identity as a spin of the dice, an openness to the next cultural turn. The ���coldness��� remarked upon by so many . . . is probably the cost of this opportunistic fluidity; a matter of ���loving the alien���, indeed.���

More recently, our deputy editor Alan Jenkins took to this blog to ask readers to "give five minutes of their time to Where Are We Now? ��� song-plus-video ��� and share in the elation I imagine all TLS readers must feel at the arrival of a masterpiece. It is a slow, very slow song, full of brought-low sadness and high drama, announcing itself from its first crashing piano chords as utterly, inimitably a Bowie song ��� and a 'big' one, perhaps a huge one, of the magnitude of Always Crashing in the Same Car, Heroes and Fantastic Voyage; and it is to the musical and emotional ambience ��� whirling synthesizers, echoey drums, throat-tightening melody, hair-raisingly exposed, yearning lyric ��� of Bowie���s great Berlin years, the years of Low, Heroes and Lodger, that this song explicitly, elegiacally returns . . . 'We could steal time', Bowie sang in 'Heroes'; the singer of 'Where Are We Now?' knows that time is stealing him, his friends, his life".

David Bowie's final song, "Lazarus", was released last week. In the music video Bowie sings from a hospital bed, a bandage around his head with buttons sown on for eyes. The song ends, "Oh I���ll be free / Just like that bluebird / Oh I���ll be free / Ain���t that just like me"; and the singer disappears, as if pulled back, into a dark wardrobe. It would appear that he even colluded in the presentation of his death.

Wesley Stace on "David Bowie, magpie and chameleon"

Pat Kane on "The Thin White Duke"

The Tonsons and their poets

Photo: National Portrait Gallery, London

By MICHAEL CAINES

Publishing in the eighteenth century was meant to be a disreputable business. The standard caricature of Grub Street is of a literary alley-way infested with parasites and plagiarists. Among others lurking there you might find the bookseller Edmund Curll, who regularly ran into trouble with fellow booksellers, authors and the authorities. Curll's reputation has improved as scholars have reassessed his astutely impudent, innovative side; but there is no gainsaying such misfortunes as his hour in the stocks (a potentially fatal punishment, given how the public could treat the condemned), Alexander Pope tricking him into drinking an emetic for publishing his work without permission, and the pupils at Westminster School making him kneel and beg forgiveness, then tossing him in a blanket.

Such associates were not for every aspiring writer, especially those who fancied making their way in the world via polite society, in order to gain the ear of an affluent and free-handed patron. It was better to be seen to be above business altogether, disreputable or not, while exploiting whatever scarce possibilities for personal enrichment publication had to offer. Hence the back-handed compliment Alexander Pope could pay the great Jacob Tonson, as noted in a review by Norma Clarke in the latest TLS ��� that he was "least a bookseller". . .

I think it's fairer to say that Tonson ��� "Genial Jacob" to those of his authors who liked him, and whom he treated to feasts when contracts were signed ��� was a model of what a bookseller could be, just as Curll has been generally dismissed as his antithesis (although they did, in fact, collaborate).

Born during the Interregnum and setting up independently as a bookseller in the late 1670s, Tonson published many smart new editions of the classics, as well as the works of Dryden, Congreve and Pope. His relationship with Dryden wasn't always easy, but they formed a lucrative alliance together, and came up with an influential form of anthology (their series of "Poetic Miscellanies"). Over time, Tonson also acquired the rights to Milton's Paradise Lost, which he brought out in 1688 with authoritative emendations from Milton's manuscript, and which he continued to champion throughout his life. He could make the celebrated claim in later life that Milton was the poet who had made him the most money.

Under the care of his nephew, a second Jacob, the firm that Tonson established would go on to publish several editions of Shakespeare, boldly claiming his plays as "vernacular classics" in the process. It wasn't Shakespeare alone who benefited from such renewed enthusiasm. Stephen Bernard, the editor of The Literary Correspondences of the Tonsons (the subject of Professor Clarke's review), suggests it would be no exaggeration "to claim that the house of Tonson invented English literature as matter for repeated reading and study".

Not that this was a disinterested achievement. There was, of course, plenty of money to be made, and Tonson certainly knew how to make it; there was also a political stake in laying claim to an English literary canon. Tonson had powerful friends in political circles, and hosted the meetings of the Whig clique known as the Kit-Cat Club, which included several of his authors (such as Congreve, Addison and Steele). Suggesting a line of native literary descent was apparently in their interest. Tonson did his part by publishing not only uniform, duodecimo editions of earlier poets such as Suckling, Cowley and Milton, but also a counterpart series of contemporary authors ��� most of them Whigs, such as Addison. Pope, a Tory and a discovery by Tonson's nephew Jacob, was a notable exception.

The implication, David Foxon has observed, is that "along with Milton and Shakespeare, these were the English classics". Various scholars have written about the relationship between establishing what the classics are, taking them over in a proprietary way, as Tonson did, and then distinguishing (or condemning) modern writers accordingly; I won't go into the full argument here, but make do with these lines by Richard Blackmore, from a poem of 1708 called The Kit-Cats, to hint, in the appropriate poetic idiom of the time, at Tonson's thinking and the effects of his encouraging hospitality:

Here he assembled his Poetic Tribe,

Past Labours to Reward, and new ones to prescribe;

Hence did th'Assembly's Title first arise,

And Kit Cat Wits sprung first from Kit-Cat's Pyes . . .

The Languid Muses, now, new Life acquire,

And every Genius feels his native Fire.

The cheerful Bards their weekly Work reherse,

And noble Subjects sing in noble Verse.

Not everybody's muse received adequate remuneration, however, even after acquiring new life. Norma Clarke notes the complaint Tonson received from John Oldmixon, the dutiful Whig pamphleteer, poet and later historian, as he was banished to Bridgwater in Somerset to act as customs collector, where he was "vilifyd, insulted & having not a Minutes Ease": "Long have I been in the Service of the Muse & the Press Without any Reward & the Life I lead here is not worth living". It's somehow a relief to learn that even The Literary Correspondences of the Tonsons contains such lively signs of Grub Street at work.

In the new episode of TLS Voices, we focus on a small selection from the poetic, English side of Tonson's output: poems by Aphra Behn, the Earl of Rochester and Pope, as well as a short passage from Paradise Lost:

January 7, 2016

Pierre Boulez and the sound universe

Photo Mike Powell/Times Newspapers Ltd

News of the death of Pierre Boulez ��� the composer, conductor, innovator and then icon ��� comes several months after the conclusion of celebrations marking his ninetieth birthday. Boulez���s was a long life of notable achievements: the seminal serialism of Le marteau sans ma��tre (1955); an international conducting career; many notable recordings of a wide orchestral repertoire; instigating the Cit�� de la Musique in Paris's Parc de la Villette; the live electronics of R��pons (1981) that emerged from his research centre in Paris, the Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique (IRCAM), opened in 1977. That was also the year in which Boulez���s wise words about technology and music appeared in the TLS. . . .

Boulez is far from being the only musician who���s written for the paper. For one thing, there���s a band of notable composers who have shown in the TLS they can write critical prose, as well as musical notes for performance, with Hugh Wood, Judith Weir and Thomas Ad��s among them. (And in the early years, Elgar contributed a few erudite letters on literary notes, including Tennyson's use of the word "poluphloisboisterous".) Yet "Technology and the composer", published on May 6, 1977, may be of especial interest, being all but a personal manifesto in impersonal guise. It mentions no composer or piece of music by name, but bears a clear relation to Boulez's work at the time; it also, characteristically, asks keen questions concerning music's future.

���Technology and the composer��� was the first English translation (the translator remains anonymous) of a piece that had only appeared earlier that year in French, in IRCAM's Passage du XXe si��cle. "Invention, in music", it begins, "is often subject to prohibitions and taboos which it would be dangerous to transgress." (Perhaps he was thinking back to the time when he and the ethno-musicologist Andr�� Schaeffner smuggled "gongs and tam-tams through the cellars of the Palais de Chaillot, no doubt to avoid the time, paper and expense involved in any French bureaucratic exercise".) Western culture in the twentieth century, as Boulez saw it, was "oriented towards historicism and conservation":

"As though by a defensive reflex, the greater and more powerful our technological progress, the more timidly has our culture retracted to what it sees as the immutable and imperishable values of the past. . . . Thus the 'museum' has become the centre of musical life, together with the almost obsessive preoccupation with reproducing as faithfully as possible all the conditions of the past. This exclusive historicism is a revealing symptom of the dangers a culture runs when it confesses its own poverty so openly: it is engaged not in making models, nor in destroying them in order to create fresh ones, but in reconstructing them and venerating them like totems, as symbols of a golden age which has been totally abolished."

The consequences of this backward-listening attitude, Boulez argues, include the lack of invention in the making of musical instruments themselves, at least as far as the concert hall goes (it was a different matter "in a field like pop music where there are no historical constraints"; although pop music today has heritage issues of its own), and knowing what to do with techniques of "recording, backing, transmission, reproduction", which have "developed to the point where they have betrayed their primary objective, which was faithful reproduction". Classical music had reached a crossroads: a choice between "a conservative historicism which, if it does not altogether block innovation, clearly diminishes it" or a "progressive technology whose force of expression and development are sidetracked into a proliferation of material means which may or may not be in accord with genuine musical thought".

In the end, Boulez opts for a third way, trying to attain "global, generalizable solutions" rather than solutions "which somehow remain the composer's personal property". He could relish the chance that an institution such as IRCAM (which is not mentioned by name) offered him to explore the "geography of the sound universe", using the "reasoned extension of the material" to "inspire new modes of thought"; better this than recoil from the potentially "vast, chaotic and if not inorganic at least unorganized" field of electronics and computers.

Almost forty years on, some of Boulez's TLS essay may sound outdated; with the capacity for making electronic music available on your smartphone, perhaps it sounds itself like an emanation from a musical museum. Yet we might also say that the essay's central point ��� about a questioning awareness of artistic possibilities, defined by economics as much as critical orthodoxies, about creativity and the weight of history playing against innovation and the disciplined use of technology ��� still expresses a real challenge for all artists.

Reading Paul Griffiths���s account of those ninetieth birthday celebrations reminds me that the extraordinary thing about the ���extraordinary Boulez story��� is how completely he took up and lived out that challenge himself. His sense of progress had its enemies, of course: in 1996, on the transferral of the former culture minister Andr�� Malraux���s remains to the Panth��on, Boulez muttered publicly about the canonization of a man who had spent so much of his life ���dans les fum��es du whisky et l���opium���; presumably, Malraux���s dismissal of his plans for ���thorough reform of the state-run musical institutions���, thirty years earlier, had not been entirely forgotten.

How different things must have looked to Boulez in 1977, with the state-funded IRCAM open for business and the geography of the sound universe being mapped out before him.

December 30, 2015

The TLS in 2015

By TOBY LICHTIG

On the app this week we are offering a comprehensive, free selection of TLS articles from the year gone by. For devoted readers of the paper this will be a look back on 2015. For those new to it we hope you���ll enjoy a taster of what we do. The articles gathered here, like those gathered every week, cover a broad range of subjects, from the latest in fiction and fashion, anthropology and philosophy; science, travel, music, history, classics and film. And within those categories our writers range far and wide to report on, and critique, advances in scholarship; new attempts by writers and artists to express and understand the world in which we live.

Peter Coates considers how horses revolutionized indigenous America, Lydia Wilson assesses the avoidable aspects of the ongoing tragedy in Syria, while Peter Thonemann revisits the myths of Troy. David Papineau wonders where all the female philosophers have gone and Wendy Slater finds New Soviet Man alive and well in Transnistria. Sean O���Brien reflects on the young T. S. Eliot; Rona Cran on James Baldwin���s maverick approach to life; Emelyne Godfrey on the suffragette movement, a century on. We offer reviews of novels by Elizabeth Harrower, William Boyd and the latest Booker Prize-winner Marlon James. The many other contributions ��� by Raymond Tallis on mortality, Michael Hofmann on Bertolt Brecht, Mika Ross-Southall on fashion and society, Jay Rubin on the Japanese language, Christine Toomey on disaster tourism, to name a few ��� attest to the lifeblood of the TLS: serious analysis and well-argued opinion, backed up by stylish writing that aims to be a pleasure for the mind. We hope you enjoy reading, and we offer our best wishes for the forthcoming year. To download the TLS app and enjoy our complimentary selection from 2015, click here.

December 22, 2015

Drinks before noon!

���The Worship of Bacchus��� by George Cruikshank (1860���62); Tate. Presented by R. E. Lofft and friends in 1869

By ANDREW IRWIN

It���s almost Christmas. And while there are stockings, turkey and mince pies to look forward to, the star of the show is obviously the rare acceptability of pre- (and post-) noon drinking. And so what would be more fitting for a grey December afternoon than a visit to Tate Britain���s BP spotlight, Art and Alcohol? According to Tate���s website, the one-room exhibition ��� curated by David Blayney Brown ��� ���examines the role of alcohol in British art from the nineteenth century to modern day���, as well as its ���catalytic effect���.

One might be forgiven for expecting an exploration of various artists��� relationship with alcohol as they sought Rimbaud���s ���d��r��glement de tous les sens��� ��� perhaps even an eager celebration of alcohol as inspiration, or a trigger for the Bacchanalian spirit of unbridled creativity. But no: what Tate presents is a whistle-stop tour through artists��� engagement with Britain���s changing views on alcohol.

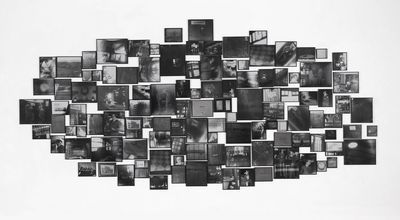

At the core of the show are two major pieces: George Cruikshank���s ���The Worship of Bacchus��� (1860���62) and, on the wall opposite it, "Balls: The evening before the morning after ��� drinking sculpture��� (1972), a multi-photograph installation by Gilbert and George. These two works, for all their dissimilarities in theme, tone and message, have a remarkable consonance.

Cruikshank���s is as didactic a work as one could imagine ��� a hellish image, in browns, blacks and greys, of a country overtaken by alcohol. The air is thick with smoke, and the top of the painting is lined with buildings ��� the police station, the lunatic asylum, the house of correction, alongside the brewery and distillery. At the centre is a statue of Bacchus; all around it revellers drink and dance, oblivious to the decay and poverty they leave in their wake. Other images crowd the scene ��� tableaux demonstrating the hypocrisy of a society whose very institutions are built on drink. As if Cruikshank feared his message too subtle, he has one man dancing on a tomb marked ���Sacrificed at the shrine of Bacchus���. The eye can barely settle, being drawn from scene to scene, face to face. A dour message, perhaps, but a dizzying spectacle.

Gilbert and George���s ���sculpture��� has much the same quality. Composed of 114 black-and-white photographs, all taken in the Balls Brothers Bar in Bethnal Green (London E2), the piece is a mimetic take on drunkenness itself. The photographs vary in both size and clarity ��� a fractured set of images on which it is difficult to focus before the gaze drifts. Hazy photographs of the artists, taken from uncomfortable angles, sit alongside images of the floor, a row of bottles, jocular bar signs, a decapitated body holding a glass ��� like an avalanche of grey, guilty memories.

"Balls: The evening before the morning after ��� drinking sculpture��� (1972) by Gilbert and George; Tate. Purchased in 1972

The other paintings in the exhibition include William Mulready���s ���Returning from the Ale-House��� (1809), in which two men amble drunkenly through a vibrant bucolic landscape; a group of children surrounds them. It is an almost affectionate portrayal, but when the painting was exhibited it met with public disapproval, and sold only in 1840, after the title was changed to ���Fair Time���.

David Wilkie���s ���The Village Holiday��� (1809���11) is similar in subject matter; but with its overcast sky and more muted colour palette, it seems less benevolent. At the painting���s centre, a man outside the tavern is tugged in both directions ��� on one side are his friends, clad in reds and blacks, pulling him back to the bar; on the other, his wife and child, in blue and white and cream, try to lead him away.

Robert Braithwaite Martineau���s ���The Last Day in The Old Home��� (1862) presents an aristocratic family on the verge of losing its ancestral estate (all dark woods and suits of armour). The husband blithely raises a glass, encouraging his son to do the same. Julius Caesar Ibbetson���s pair ���A Married Sailor���s Return��� and ���An Unmarried Sailor���s Return��� (c.1800) contrasts two scenes. In one, a seaman sits at a table opposite his wife, with his children and dog jostling for his attention. In the other, a bar full of women and dancing awaits him. The former, apparently, is the artist���s prescription.

The whole exhibition is curated as a series of binaries, nicely captured in Wilkie���s man torn between drinking and home. There is the shift from the artist as distant eye, passing judgement on others, to the artist as his own subject (as with Gilbert and George). And there is, naturally, the conflict between alcohol as benign pleasure and destructive vice. Something to consider, perhaps, on Christmas morning.

"The Last Day in the Old Home" (1862) by Robert Braithwaite Martineau; Tate; presented by E. H. Martineau, 1896

Art and Alcohol, a free exhibition, runs until autumn 2016.

December 18, 2015

Morrissey and Elizabeth Smart

By ROBERT POTTS

Morrissey fans may not be delighted by Ben Eastham's review of the novel List of the Lost in this week's TLS (December 18 & 25); our reviewer concludes, as many critics have done, that the legendary Mancunian song-writer has not transferred his exceptional talents from one genre to another. But they may gain a little satisfaction from spotting our Fiction Editor's subtle, un-signposted juxtaposition of that review with Claire Lowdon's of By Grand Station Central I Sat Down And Wept by Elizabeth Smart, one of Morrissey's favourite books, and one which has been alluded to throughout his song-writing career.

"Grabs and devours" ("The Headmaster Ritual"), "louder than bombs" (an album title), "reel around the cafe" ("Reel Around The Fountain"), "rocks below" ("Shakespeare's Sister" ��� a multiply allusive title in itself), " . . . do you hear me where you sleep?", "the fierce last stand of all I have" ("Well I Wonder") are all phrases and lines from Smart's novel. And there are many, many more: a diligent fan has listed them ��� along with scores of other references to various films, songs and books ��� here.

Morrissey's work was allusive from the start, and purposefully so. The works to which he lightly pays homage ��� A Taste of Honey by Shelagh Delaney, Brighton Rock by Graham Greene, George Eliot's Middlemarch, the writing of Oscar Wilde and Joe Orton, the Carry On Films, a book about the Moors Murderers, etc ��� all contributed to the atmosphere of the songs, rooted in the topography of Manchester and Lancashire, constantly nostalgic for the culture of the 1950s and 60s, delicately queer, defiantly provincial and working-class, romanticizing (or lusting after) young hooligans and then ironizing that very romanticization (most strikingly in "Last of the International Playboys", "Sweet and Tender Hooligan", and "First of the Gang", where the Genet-esque passion for the hoodlum is acknowledged, and deflated, in the final verse: "And he stole from the rich / and the poor / and the not very rich / and the very poor. . . . He stole our hearts away").

The borrowings, thefts and tributes are calculated: one of the first I ever noticed myself was his adaptation of the Leonard Cohen line "And everything depends upon how near you sleep to me" ("Take This Longing"), which became "And everything depends upon how near you stand to me" ("Hand in Glove"). The alteration of one word, from "sleep" to "stand", marked a shift from the erotic to the platonic at a time when celibacy was a significant feature of Morrissey's self-presentation. And Morrissey, a Wildean ironist at his best, was also able to comment on his own processes, in "Cemetery Gates", for example, a song ostensibly mocking plagiarism while borrowing from Shakespeare's Richard II and the film The Man Who Came To Dinner (1942; based on the play by Kaufman and Hart), and even precisely situating his own version of romanticism ("Keats and Yeats are on your side / While Wilde is on mine").

This is one reason, I imagine, why some lifelong fans of the music have been so disappointed by Morrissey's novel. His literary intelligence, unobtrusively active within scores of ravishing pop songs, would lead one to expect a better result. A critical work on the music ��� The Pageant of His Bleeding Heart by Gavin Hopps ��� does an excellent job of drawing out Morrissey's literary techniques and influences, and makes a great case for him as a modern-day Orton or Wilde. Given that heritage, perhaps he should turn his talents to writing plays? Or subversive musicals? Or maybe just stick to what he has always done best of all.

See also: Morrissey unbowed (from the TLS blog, August 30, 2013); and Morrissey, this elusive man (from the TLS of November 8, 2013).

December 16, 2015

Proust biography: The gift that keeps giving

Nadar's portrait (1892) of a twenty-one-year-old Marcel Proust on the cover of Benjamin Taylor's short biography

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Do we need another biography of Marcel Proust? Almost certainly not. After all, only in 2013 Adam Watt brought out his excellent short Life (Reaktion). And, while we're on the subject of short Lives, there is Edmund White���s breezy 150-page book of 1999. Also within the past twenty years we have had door-stoppers by the pre-eminent Proust scholar in France, Jean-Yves Tadi��, and by the American academic William C. Carter.

None of this appears to have deterred Benjamin Taylor, whose Proust: The search has recently been published in Yale���s Jewish Lives series. (The Jewish Lives list is an eclectic one, ranging from Sarah Bernhardt to Einstein, from Moshe Dayan to Peggy Guggenheim. Forthcoming are biographies of Jesus, Benjamin Disraeli, Rabin, Barbra Streisand and Bob Dylan, among others.) Taylor is the editor of Saul Bellow���s Letters, published in 2010. His new book comes with a ringing endorsement from Philip Roth: ���Those who found reading Proust too grand an undertaking over the years because of distractions and deficiencies of their own, might well rush to reconsider after confronting this dazzlingly elegant biography���. Praise indeed! I particularly like ���distractions and deficiencies of their own���. Anka Muhlstein, author of the enjoyable Monsieur Proust���s Library, calls it ���a very subtle, thought-provoking book���.

Taylor���s book is indeed elegant, but for this pedantic reader there are rather too many typos as well as omitted French accents ��� surprising to see in a book from such a prestigious press: I spotted ���Faubourg-Poissoni��re��� rather than Faubourg-Poissonni��re, ���cinqieme (eighth grade)��� rather than cinqui��me, ���grandes lyc��es��� rather than grands lyc��es, Guy ���du��� Maupassant rather than de, Jean ���Giradoux��� for Giraudoux, ���Tannha��ser��� rather than Tannh��user, ���path��onisation��� for panth��onisation, Nouvelle Review Fran��aise (twice) for Nouvelle Revue Fran��aise, preceding a paragraph in which Taylor notes that there are more than 1,000 misprints in Grasset���s first edition of Swann���s Way, ���M��seglie" (ouch) for M��s��glise. Elsewhere we have ���Batallion���, ���stationary��� for stationery, Dreyfus���s ���court-marital���, an ���indeliable��� portrait. These errors suggest careless proofreading or, perhaps, an unfamiliarity with French-language material ��� a bit of a drawback if one���s tackling Proust.

And yet Taylor���s book has much to commend it. He is particularly good on the way the Dreyfus affair and its consequences are woven into the fabric of the novel. He reminds us of how poisonously anti-Semitic some people Proust regarded as friends could be ��� the staunchly anti-Dreyfusard L��on Daudet, whom Taylor describes as ���virulently bigoted all his life���, for example. Daudet was the dedicatee of The Guermantes Way. Shortly before he died, Proust arranged for flowers to be sent to him in gratitude for his laudatory article on the novel in . . . Action fran��aise (a far-right publication). It all seems rather strange in retrospect.

Proust: The search will be reviewed in a forthcoming issue of the TLS.

December 13, 2015

John Donne in verse and prose

I am a little world made cunningly

Of Elements, and an Angelike spright,

But black sinne hath betraid to endlesse night

My worlds both parts, and (oh) both parts must die. . . .

The thirty-fifth episode of TLS Voices complements the lead review in this week's paper, in which Russ McDonald considers John Donne and how the critics and scholars are far from being (let's get the obvious pun over with) done with him.

"Of course", McDonald recalls being told by a young colleague recently, "everybody likes Donne." Well, a guardedly gushing Ben Jonson did call him "the first poet in the world in some things" (where does the emphasis in that sentence fall ��� on the unspecified "some things"?). And despite those who, between our time and his, "demoted and mostly neglected him", Jack Donne the poet has remained popular. The same cannot be said of Dr Donne of St Paul's Cathedral ��� one of "Gods conduits", as he called those "grave Divines" whose works, in his first Satire, help to fill the poet's wooden chest of books.

In 1921, T. S. Eliot could write in the TLS of that "metaphysical" strain of verse in which Donne excelled, of the "brief words and sudden contrasts". Two years earlier, though, Arthur Clutton-Brock could talk of a selection from Donne's sermons revealing "wonderful living fragments of art, of eloquence, of passion". "The worst fault of the sermon, as literature, is that it is preaching" ��� whatever common ground of belief securely connected those who heard Donne preach at St Paul's (or, some years earlier, John Knox in Edinburgh), Clutton-Brock could not share it. "The great poet was not lost in the preacher, but transmuted. . . . he remained a wild poet like Poe even when he tried to speak the language of a dean."

Both guises have their wonders, certainly, and their admirers, as shown once more by the books McDonald reviews: Achsah Guibbory's essays of the past thirty years; Daniel Starza Smith's study of the circulation of Donne's poems in manuscript; and the new Oxford edition of Donne's sermons, with its innovative approach to "some of the liveliest and most eloquent prose in English". (Some miscellaneous further signs of these critical times: this earlier Donne survey; Starza Smith's fascinating account of "Good Friday, 1613. Riding Westward", published a couple of years ago; and, if you can track down a copy, Maureen Duffy's poem "In St Paul's ��� for Jack Donne".) On St Lucy's day, December 13, marked by Donne in an alchemical, twisting "Nocturnal", this selection for TLS Voices concentrates on a selection of the most dramatic poems by a poet who never wrote a play, but put Eliot in mind of Shakespeare, Webster and Middleton.

December 12, 2015

Love and death: re-viewing Hitchcock's 'Vertigo'

By DAVID COLLARD

D'entre les Morts is a modestly competent psychological thriller by the French writing duo known as Boileau-Narcejac, first published in 1954. It's fair to say that it would attract little attention today had it not formed the basis of Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo. The novel was recently republished in English, and I was delighted to be given the chance to review it, because the film has been a personal obsession since I saw a faded print screened in a Manchester flea-pit nearly forty years ago. After multiple viewings it remains as fresh and complex and alluring as ever, one of a handful of films that deserve and repay close attention over decades. It is an undisputed masterpiece, although on its release in 1958 the director's forty-fifth feature met with a lukewarm reception and would not appear in the Sight & Sound critics' poll until 1982, when it came seventh. In the most recent poll it was voted the greatest film of all time, displacing Citizen Kane, which had occupied the top spot since the poll began fifty years ago. Such lists count for little, but if pushed I'd argue that Hitchcock is a greater director than Orson Welles while Welles is the greater artist. This is the kind of distinction that used to prompt heated exchanges in the bar of the old National Film Theatre, spiritual home to many a passionate cineaste.

Reading the novel, one experiences (as I note in my TLS review) an unnerving sense of d��j�� lu, because although the setting is Paris and Marseilles before and after the German Occupation, the premiss is immediately familiar: a wealthy industrialist employs an ex-cop to keep an eye on his troubled wife, Madeleine, who appears to be possessed by the spirit of a dead ancestor. The cop soon becomes infatuated with her, attracted by her chilly glamour and aura of sadness, and when he witnesses her apparent suicide he becomes a melancholy, deracinated alcoholic. He later encounters another woman, appropriately named Ren��e, who appears to be Madeleine's double, her reincarnation. He attempts obsessively to re-make her in the image of his dead lover, scrupulously selecting her outfits, jewellery, make-up and hair (women's hair is a recurring motif in Hitchcock's oeuvre).

Vertigo is an intensely romantic film, but also profoundly morbid. There's a whiff of necrophilia in the movie, and considerably more than a whiff in the novel, where even Madeleine's perfume, Chanel No. 3, is headily redolent of ���fresh earth and wilting flowers���. The besotted cop single-mindedly pursues his fantasy, described bluntly by Hitchcock in an interview with Fran��ois Truffaut thus: ���He wants to sleep with a dead woman���.

The director's perverse genius extended beyond a transgressive modern take on the Eurydice myth to explore themes of power and freedom; the power of men over women, of human beings over their fate and our dreams of freedom from death. Hitchcock wasn't especially interested in the mechanics of plotting, and audaciously gave the secret away thirty minutes before the end of the film in a combination of flashback and voiceover. What interested him ��� and what makes the film a timeless pleasure ��� is the human dilemma, the dreamy mutability of Kim Novak, who delivers one of cinema's greatest performances.

Later in the Truffaut interview Hitchcock also said: ���Some films are a slice of life. Mine are a slice of cake���. Surely what he intended to say ��� and quite possibly said, using an idiom lost in translation ��� was: ���Some films are a slice of life. Mine are a piece of cake���. This casual dismissal of his astonishing virtuosity served to deflect attention from the private obsessions and fears that he smuggled on to the screen, for a popular audience hungry for distraction, sensation and entertainment.

A postscript: I recorded this podcast while suffering from the effects of a bout of flu. This is my only defence for confusing Los Angeles with San Francisco. On hearing this gaffe on the playback I broke into a cold sweat, or sueurs froides which is, as it happens, the French title of the movie.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers