Peter Stothard's Blog, page 10

April 4, 2016

Eric Ravilious in Eastbourne

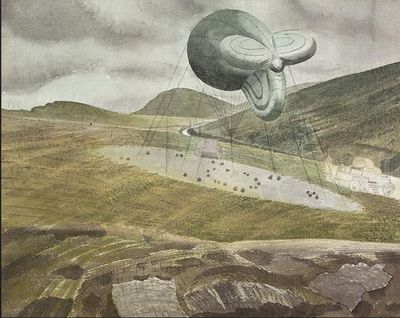

"Barrage Balloons" by Eric Ravilious ��� copyright Towner gallery

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Claude Debussy probably didn���t have the English Channel in mind when he wrote La Mer. He did, however, complete the piece while staying in Eastbourne���s Grand Hotel in the summer of 1905. The Grand still stands elegantly on the seafront. A few minutes��� walk away from the seafront is the Towner gallery, a modern space (all concrete and glass) dedicated to contemporary art. The Towner, together with the Jerwood Gallery in Hastings and the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill-on-Sea, forms a fine trio of galleries all within 25 miles of each other on the South coast. Brighton, further west up the coast and home to two universities and several art colleges, has nothing to match them.

Recording Britain, an attractive small exhibition at the Towner (until May 2, admission free), draws on work from the V&A���s collections. At the outbreak of the Second World War, Kenneth Civilisation Clark ���commissioned artists to paint ���places and buildings of characteristic national interest���, documenting rural and urban environments and precious buildings under threat, not only from bombs but from the effects of ���progress��� and development���. The project resulted in 1,500 watercolours, which went on show around the country in order to, in Clark���s words, ���inspire the war effort and boost public morale���. Forty-nine of these works are on display in Eastbourne.

The critic Michael Rothenstein wrote in World Review London in 1942: ���The zeal with which men are prepared to defend their country is sometimes inseparable from an image they carry in their own minds of the tract of countryside they hold most dear���. He may have had in mind the atmospheric watercolour by Mona Moore (1917���2000) of an ���open tract of wild countryside��� in Breckland, Norfolk (1941) or maybe the depiction of a ���Cricket Green, Great Bentley, Essex��� in 1940 by Walter Bayes (1869���1956), a founder member of the Camden Town Group. On the green a game of cricket is taking place, watched by a few leisurely spectators while, presumably, not so far away the Battle of Britain is in its early stages.

In an adjoining room is a fine display of works by Eric Ravilious (1903���42) that ���record the British landscape, in particular Sussex, at a time when the threat of war was imminent���. (An exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery last year displayed more than eighty works by him.) Ravilious had been invited by Clark in 1939 to become a war artist for the War Artists Advisory Committee. The resulting work includes military aircraft and barrage balloons against the backdrop of the Sussex Downs. Towner claims to hold ���one of the largest public collections of works��� by Ravilious who disappeared in an RAF plane on a search-and-rescue operation in September 1942 off Iceland.

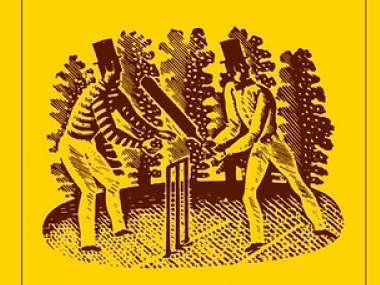

The 150th edition of the Wisden Cricketers��� Almanack in 2013 contained an eloquent tribute to Ravilious by his great-nephew Rupert Bates. As Bates writes, ���a batsman and a wicketkeeper ��� both nameless, both virtually faceless ��� have adorned Wisden now for 76 springs. The wood engraving of the Victorian duo in top hats is one of the sport���s most charming and recognisable images. And yet cricket knows little of its creator���. Although he claimed no talent as a cricketer, Ravilious wrote: ���It is, you might say, one of the pleasures of life, hitting a six���.

According to Bates, the Daily Telegraph called Ravilious "the greatest artistic loss Britain suffered in the Second World War���, while the Observer���s art critic Laura Cumming described him as ���the lost genius of British art���.

March 31, 2016

Where were you when . . . ?

One of the pleasures of press day (on any paper, I should hope) is seeing readers' letters fall into place on the page, and marvelling at the unique knowledge they're prepared to share (when they're not spoiling for a fight, that is). The example below, from this week's issue of the TLS, begins as a response to some observations in the paper's NB column about the current scarcity of decent second-hand bookshops in Oxford, and turns into something else . . . .

"Sir, ��� I served as an American airman at RAF Upper Heyford outside Oxford from 1958 to 1961. Coming from a small town in Wisconsin that had no bookshops, I was delighted by the choices Oxford offered crew-cut Yank bibliophiles back in those tweedy times. My favourite was John Booksellers then in St Michael���s Street. On November 2, 1960, I was talking to John himself on the second floor when three undergraduates came thundering up the staircase shouting ���Lady Chatterley not guilty. Five copies please���. John made a phone call to confirm the verdict, and told the lads the official publication date was about a week off, but sold them a single copy from a stash behind the counter for 3/6. I settled for a copy of The Horse���s Mouth.

ROBERT NEUMAN

635 El Toro Way, Davis, California 95618."

(That link I've added, by the way, takes you to a masterly survey of Joyce Cary's reissued novels, including The Horse's Mouth, by Karl Miller; the piece happens to begin with a nod to Lawrence.)

Obstreperous customers, verbose customers, bores and drunks I've all encountered in bookshops, but never, in these enlightened times, undergraduates demanding "not guilty" D. H. Lawrence. Nor have I been sold Lady C from a secret stash behind the counter. I've been shopping in the wrong places, clearly.

Anyway: now you know where Mr Neuman was on that November afternoon when a jury of nine men and three women, after three hours' deliberation, found Penguin Books not guilty of "publishing an obscene article", in the form of Lawrence's novel. And thanks to the Evening Standard, pictured above, you know vaguely where Sir Allen Lane was, too: he "ran from the Old Bailey . . . to meet a barrage of waving hands outstretched in congratulation", although the paper declines to reveal where this barrage lay in waiting for Lawrence's champion. So if you happen to be old enough to remember and literary enough to care ��� where were you?

This question would be a less ghoulish literary-historical equivalent to the well-worn question of remembering where you were when JFK was assassinated ��� only literary history is, for the most part, an unhelpfully quiet affair, largely consisting of births, deaths and publication dates. Where were you when the last Harry Potter was published? In a queue outside Waterstones doesn't quite cut it, and nor does the initial question exactly quicken the pulse. It doesn't quicken mine at least. (That said, I have occasionally stayed up all night to read a new book in one delinquent gulp. Wild stuff, I know.) How about the doling-out of literary prizes? Too regular to be exciting.

And deaths? Well, morbidly perhaps, this version of where-were-you-when is a subject in its own right, and has been thought worthy of its own chronicles. I think there's a Penguin or Oxford edition of Hardy that recalls a headmaster who, in 1928, had broken down in tears while announcing to the school that the author had died. There is a whole book of responses (more than 200 letters), edited by Sybil Oldfield, to the death of Virginia Woolf in 1941. There is the awful story of Ted Hughes guiltily circling the memory of where he was and what he was doing on the night of another suicide: that of Sylvia Plath in February 1963 ��� which the recent "unauthorised Life" by Jonathan Bate has had some readers circling in turn.

More happily, and as mentioned previously on this blog, a celebration of Henry James took place earlier this month, on the centenary of his death. Professor Philip Horne of UCL organized this event, at Chelsea Old Church. That I hope I'll remember for a long time to come, not least for the fine leafy weather to cheer up what could have been a rather sombre occasion, and the excellent readings by the actors Simon Paisley Day, Miriam Margolyes and Olivia Williams, as well as Alan Hollinghurst, Tessa Hadley, Dr Oliver Herford and Professor Horne himself. What Maisie Knew was brilliantly disdainful yet moving; Daisy Miller was enticingly humorous (with Margolyes as the nine-year-old Randolph Miller); and James's riposte to that treacherous swine H. G. Wells reached far beyond its immediate purpose to magnificent, magnanimous effect. When the soprano Anna Sideris stood in front of the altar to sing "How beautiful it is", from Benjamin Britten's operatic adaptation of The Turn of Screw, that clinched it. This was art apotheosized rather than art on trial, and I'll try not to forget it . . . .

March 24, 2016

J. M. G. Le Cl��zio ��� Nobelized, but much read?

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

When J. M. G. (full name Jean-Marie Gustave) Le Cl��zio won the Nobel Prize in 2008, the Swedish Academy called him ���an author of new departures, poetic adventure and sensual ecstasy, explorer of a humanity beyond and below the reigning civilization���. This strikes me as a fine specimen of the higher waffle; either that or ��� ���beyond and below the reigning civilization���? ��� something was lost in translation. And yet I can see what they mean. Le Cl��zio has long focused on the marginalized and downtrodden in society, using his novels as a means to explore issues such as sexual exploitation, political oppression and environmental degradation. It hasn���t always made for good fiction; his last two published (and as yet untranslated) novels, Ourania (2005), and Ritournelle de la faim, published weeks before the Nobel announcement, come to mind.

But when Le Cl��zio is good, he���s very good. His first novel, Le Proc��s-verbal, published in 1963 when he was twenty-three and translated as The Interrogation, remains a strange and brilliant book. Some critics saw affinities with the nouveau roman but I think it���s out on its own: experimental, yes, but completely original. It���s arguably his best book.

Le Cl��zio with his wife Marina in 1963, after the publication of his first novel Le Proc��s-verbal

Much more recently, and in a very different vein, there has been the 560-page R��volutions (2003), which takes in post-Revolutionary France, the Algerian war and the student massacres in Mexico City in 1968. An old-fashioned historical narrative, the book is a complete page-turner; it���s a mystery to me that it hasn���t been translated into English. I think readers would lap it up.

Roughly midway between those two novels is Le Chercheur d���or (1985), largely set on the island of Mauritius (where Le Cl��zio grew up). It was a bit of a surprise to see a translation of it, by C. Dickson, arrive in the office this week: The Prospector (Atlantic Books) is published in April. It was a surprise because there has already been a translation, by Carol Marks, less than ten years ago, of what is unquestionably one of Le Cl��zio���s best novels.

The book opens thus in 1892:

���Du plus loin que je me souvienne, j���ai entendu la mer. M��l�� au vent dans les aiguilles des filaos, au vent qui ne cesse pas, m��me lorsqu���on s�����loigne des rivages et qu���on s���avance �� travers les champs de canne, c���est ce bruit qui a berc�� mon enfance.���

Here is Marks���s version of the opening:

���As far back as I can remember I have listened to the sea: to the sound of it mingling with the wind in the filao needles, the wind that never stopped blowing, even when one left the shore behind and crossed the sugarcane fields. It is the sound that cradled my childhood.���

And Dickson���s:

���As far back as I can remember, the sound of the sea has been in my ears. Mingled with that of the wind in the needles of the she-oaks, the wind that never stops, even when you leave the coast behind and cross the cane fields, it���s the sound of my childhood.���

Funny how different translations can be. The first version strikes me as more lyrical, the second more direct. I���m not sure I like ���she-oaks��� even if it appears to be technically correct. Why not keep the intriguing ���filao��� as Marks has done? I like the directness of ���it���s the sound of my childhood���; but then ���cradled my childhood��� is exact for ���berc�� mon enfance���. Thankless task being a translator.

March 21, 2016

Ebooks don���t furnish a room

By MICHAEL CAINES

You might think twice about buying eBooks after reading this. Sainsbury's takes over Nook e-books business in the UK. Apple to pay $450m settlement over US ebook price fixing. "End of the beginning for e-books", says Tamblyn (i.e. Michael Tamblyn, the CEO of the ebook service Kobo). I was prompted to look up the latest headlines about ebooks by the Channel 4 news story above, called "All in a bind".

The story stars a bookbinder whose work I've admired for some time now, Michael Curran of the Tangerine Press, as well as that man of many talents, Billy Childish ��� both of them have interesting things to say, I think, within the rather straitened either/or context of this report. It tells us that we live in an age of analogue versus digital, books versus ebooks, traditional craftsmanship versus PDFs and print-on-demand. Does it really have to be like this?

I suppose countless books will be bought and sold before anybody can give a definitive answer to that question, and the headlines quoted above show how it's early and unsettled days for the ebook business. As with the publication of short stories, though, I find it strange how often this kind of discussion is presented solely in terms of revenues and percentages. I'm not denying it's significant that ebook sales are "cruising nicely", as Mr Tamblyn puts it, at 20���30 per cent of all book sales, or that the five biggest publishers' ebook sales actually fell in the UK last year, as the reporter Boya Dee notes for C4. "The rise of the e-book may not be as unstoppable as you might think."

For me, the strangeness lies in the pitching of, say, buying Iris Murdoch's letters through Amazon, for consumption via a Kindle app (as I have done), against the unimpeachable artistic quality and value of a Tangerine Press production. Ignore the money for a moment, and there is, as Billy Childish says, no contest ��� in fact, don't ignore the money but think about what you're paying for when you buy a text in physical form. Mr Curran, a former carpenter, underlines the difference between that and its electronic twin: "it's not anything you can get hold of, it's not something you can pick up and smell; but I think when you've got an article that's hand-made . . . that's just so much more". J. C. makes a similar point in the TLS:

"Many people find convenience in ebooks and e-readers, and if they are happy, we���re happy too. . . . A book is a book is a book. You cannot own an ebook. It has no aesthetic properties: no ornamentation, no weight, no smell; in short, no character. It offers no choice between nice-to-handle and that experience���s opposite. It does not furnish a room."

(This is from J. C.'s Perambulatory Christmas Books series, by the way; it comes to mind because I did a spot of perambulating myself this morning and, on the cheap, picked up three good-looking books, from 1963, 1946 and 1927 respectively; none of them requires an update.)

On the other hand: when I say I'm consuming Iris Murdoch's letters on the Kindle, I actually mean that I'm searching them, copying and pasting lines I happen to like and carrying 688 pages around as if they weighed nothing at all; I won't be giving them a star rating on Amazon.

In other words, given the interests of the industry, setting analogue against digital no doubt makes sense ��� but some readers perhaps prefer both/and to either/or. (That's one reason I'd like the wise heads to tell me why the book world hasn't widely embraced the model of simultaneously selling readers physical and digital versions of the same title, as you sometimes find with music, film and newspapers.) For purely selfish reasons ��� and I'd be interested to know if other readers feel the same way ��� I have an as-yet-unshaken conviction that physical books are best, but I'll take what I can get, and very gladly exploit the advantages of an e-reader without feeling that this marks an evolutionary leap into the future.

One other fact whispers to me that analogue versus digital is a literary red herring: Tangerine Press specializes in publishing limited editions of neglected writers and works of a distinctly alternative spirit. I first heard of Curran's work when I reviewed his edition of The People of the Abyss by Jack London, and later went to see the workshop C4 more recently visited; since then, I've found much more to enjoy in Tangerine editions such as James Kelman's revised story collection A Lean Third, as well as In the Enemy Camp, a selection of the morphine-riddled and otherwise scarce poems of William Wantling. Can we interpret the care that goes into the making of such books as a sign of especial respect for their contents? And isn't it less a case of one format versus another, than of what a determined small press can do, and which, given the esoteric nature of such projects, it wouldn't make any sense for a a big publisher to take on?

March 18, 2016

The story of the neglected author

Sophia Loren (right) in La mortadella (1971) by Mario Monicelli Photograph Photos 12/Alamy; from Lidija Haas's TLS review of Elena Ferrante

By TOBY LICHTIG

The Man Booker International longlist was announced last week and I���m pleased to report that the TLS has covered ��� or is poised to cover ��� all thirteen books on it. It���s an interesting selection, pleasingly diverse, and it affirms, I think, the current rude health of literary translation.

The award is a new-look prize, folding in the now-defunct Independent Foreign Fiction Prize (sponsored by the soon-to-be-defunct Independent print product) with the former Man Booker International Prize, which was a rather odd biennial award for a body of work published in English or available in English translation. The new Man Booker International will run every year and is awarded for a single novel, published in the past year in English translation. The prize money is ��50,000 ��� to be shared between the author and translator. The other shortlistees each get ��2,000, to be shared in the same way.

So who���s in the running? Well the critics��� favourite must surely be Elena Ferrante for The Story of the Lost Child ��� the final instalment in the author���s Neapolitan series. Granted, the new prize is not a lifetime achievement award and The Story of the Lost Child is by no means the best book of the tetralogy (for that you���ll have to go back to Book Two: The Story of a New Name), but Ferrante���s achievement across the whole is so impressive that it would, to my mind, be a great shame if she (and her translator, Ann Goldstein) weren���t honoured for this climax to the project ��� especially given the fact she was so perversely ignored by the IFFP in previous years. Ferrante failed even to make the IFFP longlist for the first three Neapolitan novels and in fact remains entirely ungarlanded, in both Italy and abroad. Is this the biggest judging failure of recent years? And would it help if Ferrante were, instead of a pseudonymous woman who never appears in public, an intensely photogenic Norwegian male novelist famed for his leather jackets and brooding looks?

There are a couple of big hitters on the longlist with whom Ferrante has to contend: the Nobel Prize laureates Orhan Pamuk and Kenzaburo Oe. Pamuk���s novel, A Strangeness in My Mind, concerns the solitary perambulations of a boza hawker (boza is a low-alcohol drink) over forty years in Istanbul. It was given a rousing reception in the TLS by Robert Irwin, who described it as ���hugely ambitious ��� and equally successful in achieving its ambitions���. Writing in the paper next week, Mark Morris will, I might as well break the news, be rather less impressed by Oe���s Death by Water.

On the same page in next week���s paper, Kate Webb is full of praise for Han Kang���s new novel, Human Acts. I mention this because Han also appears on this year���s Man Booker longlist for her previous novel, The Vegetarian, which our critic, Peter Brown, described as ���a strange and ethereal fable, rendered stranger still by the cool precision of the prose���. (As I reported recently, Han���s translator, Deborah Smith, has already won an Arts Foundation award for her efforts in bringing the author into English.) Staying, for a moment, in Asia, the longlist also includes the Chinese author Yan Lianke and the Indonesian Eka Kurniawan. Yan���s Four Books ��� currently verboten in mainland China ��� concerns the country���s disastrous Great Leap Forward and is set in a re-education camp. Our critic Pierre Fuller was captivated by Yan���s ���earthy canvas that captures the gravity of a historical moment while also somehow transcending its time and place . . . . Yan strips a hyper-political moment down to the elements of soil, sun and smelted steel in a desolate landscape where the most basic of desires ��� to read, worship, have sex ��� are criminalized���.

Saskia Sch��fer, on the other hand, found the widespread praise being heaped on Eka Kurniawan to be rather less justified. ���Many Western critics have swooned over Eka���s ability to educate them in Indonesian political history while keeping them entertained���, wrote Sch��fer; ���they have praised his swaggering impatience with the rules of psychological realism���. Not so our critic, who concluded that ���Eka is inserting himself into an expired tradition of political critique��� and found herself drowning in ���an overdose of murderous slapstick���. For those particularly interested in Indonesia, it may be worth noting that, in the same issue, we ran an article by Tash Aw, drawing attention to some other Indonesian novelists who may perhaps be more deserving of praise than Eka Kurniawan.

But back to that list . . . . There is only one novel from South America, represented by Brazil (and curiously none at all from Spain, which means no Hispanic novels feature). A Cup of Rage by Raduan Nassar ��� who until recently was barely known outside of his home country and gave up writing many years ago to become a farmer ��� is a waif of a novella, featuring a warring couple before, during and after a passionate tryst. Lorna Scott-Fox will be reviewing it in a future issue of the paper.

Representing Africa on the list, we have Jos�� Eduardo Agualusa, whose A General Theory of Oblivion ��� which features an agoraphobic who bricks herself up in Luanda during Angola���s civil war ��� failed to pique the interest of Lara Pawson. The Congolese author, Fiston Mwanza Mujila, received a more enthusiastic write-up from Michael LaPointe for Tram 83, a ���deeply allusive���, jazz-inflected novel set in a bar in an unnamed African country (���Tram 83 seems to anticipate, and parody, its own critical reception, especially its accolades���).

There are two French novels, Mend the Living by Maylis de Kerangal and Ladivine by Marie NDiaye ��� the TLS verdicts on those are due to appear next month. The other two European entries are both novellas: White Hunger by the Finnish author Aki Ollikainen (���a striking folk tale about austerity politics���, in the words of Christina Petrie) and A Whole Life by the Austrian Robert Seethaler: an ���elegant novella��� about a mountain guide, which, for our reviewer, Laura Profumo, ���glides forwards with all the soundless wonder of an Alpine mountainscape���.

As well as no Spaniards, there are no Germans and, perhaps even more surprisingly, no Russians on the list (Oleg Pavlov anyone?). Some big names were excluded: Mario Vargas Llosa and Milan Kundera, for example (perhaps unsurprisingly, given the lukewarm reception accorded to their latest offerings), as well as Javier Mar��as and Andre�� Makine. Also notable by his absence is a certain Norwegian, who shares with Ferrante a wild and unlikely success story, both popular and critical, for a series of naturalistic novels that have been appearing in English translation over recent years. Now, though, perhaps it really is time for Elena Ferrante ��� venerated so passionately far and wide, but not, as yet, by those with the keys to the treasure. Either way we���ll find out on May 16.

March 17, 2016

In league with the novel���s wayward younger brother

By MICHAEL CAINES

A declaration of interest: I am a Liar. And I am not only a Liar, but a proudly unionized Liar: for I am a founding member of the notorious Liars' League.

This organization's sole purpose is a noble one: to bring together two species of Liar, actors and writers, to entertain an audience for one evening every month with a selection of short stories. The writers write, the actors read (sometimes doing the police in different voices), the audience listens and, as the Liars' League slogan has it, "everybody wins". I'm very much on the fringe of the group but, from that perspective, it appears to be a formula that works.

And as Liars' League approaches its ninth anniversary and its 100th event (not counting those hosted by its offshoots in New York, Hong Kong, Portland, Blackpool and various literary festivals), it would seem to prove something else, too: that that rotten old lie about the short story being dead is the worst one of the lot . . . .

A few years ago, when Liars' League was barely out of the cradle, Neil Gaiman could say this of the literary form he called "the novel's wayward younger brother":

"For at least as long as I've been alive ��� which at this point is about 50 years ��� people have been announcing that the short story is dead, and the short story anthology is dead. Like some kind of particularly tenacious vampire the short story refuses to die, and seems at this point in time to be a wonderful length for our generation. It's a perfect length to read on an iPad, your Kindle or your phone . . . ."

I admit I don't fully understand why somebody can't read more than a short story on an iPad, but it's an interesting idea that the Age of the Tablet is, if anything, an age in which the short story can flourish rather than wither. (The Liars' League idea, a complementary one, suggests that the story read aloud can be its own art form. The short story can flourish in many forms, it seems, and in some ways seems more adaptable than the novel.) If that's the case, it doesn't seem to have stopped people saying either that the short story is dead or, perhaps more often, that it was dead and now it's enjoying a renaissance.

This can be, I suspect, a rather heroic, even self-justifying or self-dramatizing stance. I only recently came across Chris Power's fine essay"The Short Story is Dead! Long Live the Short Story!", in which he traces the long history of people saying the short story is dead, and why they've said it ��� and how, just as often, other people say it's making a comeback of some sort. Just Google "short story renaissance", as Power suggests, and you'll see what he means. Google "the short story is dead", however, and the first thing that comes up is his essay (it was for me this morning, at least).

There's an obvious commercial bottom line, big publishers being understandably wary of trying to stick their fat fingers into these niche markets. On the other hand, it's also all too easy, and all too fallacious, to look back to some imagined golden age, rather than recognize a more complicated history of good periods (the science fiction Golden Age, say) and bad periods (Alan Ross could write in 1963 about the "generally gloomy economics of short story writing" forcing "natural practitioners" such as V. S. Pritchett et al to write "increasingly at novel length").

Not everybody on my train or bus into town is reading Lorrie Moore or Lydia Davis or Jon McGregor or Ali Smith, of course ��� but some of them are. (And for the others, here are a couple of recently published lists of recommendations for "people convinced they don't like short stories" and those who don't consider themselves to be "English nerds".) The assumption that the short story is on its last legs seems more rhetorically useful than factually accurate. In this way, every success can be made to read as a defiant bucking of the trend. Power observes that invoking the decline of the short story has become a book reviewer's unexamined tic:

"The regularity with which the return of the short story is bruited on the books pages of most national newspapers is remarkable. It is, apparently, just what you have to say when you review a short-story collection. Why? Because that���s what all the other reviewers do. I proclaimed it once or twice in reviews of my own when I was younger for precisely that reason. What it usually means is that the reviewer isn���t thinking about what they���re writing, or that they don���t normally read short-story collections and therefore interpret their personal awakening to what the form can offer (their epiphany, so to speak) as a more general uptick of engagement. Rather than grasping that their own ignorance has decreased, they perceive the form���s quality to have grown. In this sense reviewers are like doctors before the advent of the randomised controlled trial, extrapolating the universal from the anecdotal. When this was the way medicine was done, let���s not forget, doctors killed far more people than they cured."

(By contrast, the TLS regularly reviews new collections ��� in recent weeks, collections by Helen Simpson, David Constantine and the late Lucia Berlin ��� without resorting to this tactic.)

In another sense, a pragmatic sense closer to the small but lively world of Liars' League, it's ridiculous to suggest that the short story is dead as long as writing one remains a relatively attainable goal for the would-be author ��� just as adding to the world's tedious burden of haiku is always going to seem a somewhat lighter task for the aspiring poet than, say, inventing a new and indecently complex verse form. Among the monthly submissions to Liars' League, there are always a few hastily concocted, clich��-infested attempts that border on "and then I woke up, and it was all a dream" territory; but there are also terrific knockabout farces and finely observed tales of woe. I've always found it striking that we end up reading across such a spectrum of talent, from have-a-go heroics to powerful work by professional and might-as-well-be-professional types (Helen Simpson included). And to be told that the short story is dead ��� or making some sudden comeback ��� seems even stranger in the light of this almost decade-long experience. My fellow Liars ��� I salute you!

March 16, 2016

How money behaves

By DAVID COLLARD

Some lines from the poem "Behaviour of Money" by Bernard Spender (Poems 1940���1942) came to mind on a balmy Saturday afternoon earlier this month, when I attended a one-day event called The Maximum Wage: A performance publishing extravaganza.

"The poor were shunted nearer to beasts. The cops recruited.

The rich became a foreign community. Up there leaped

quiet folk gone nasty,

quite strangely distorted, like a photograph that has slipped."

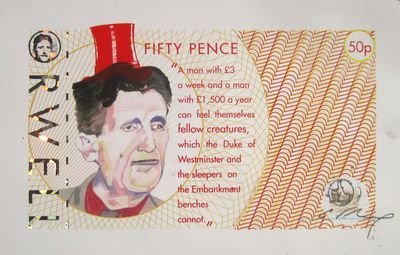

Hosted by the artists David and Ping Henningham, collaborating as Henningham Family Press, Maximum Wage was inspired by an observation made by George Orwell in his essay "The Lion and the Unicorn" (1941): "A man with ��3 a week and a man with ��1,500 a year can feel themselves fellow creatures, which the Duke of Westminster and the sleepers on the Embankment benches cannot".

The Hennighams and a cohort of artists had taken over the church hall of St Paul's West Hackney in north-east London for a lively and subversive investigation into the nature of money. I was one of the members of the public roped in to the first of five performances; we each picked a random straw which determined our status, then trooped off to dress up (in my case in plastic overshoes and apron, hairnet and surgical mask) before being briefed by Ping Henningham (dressed in a grey lycra outfit representing "the hidden hand of capitalism"). David Henningham acted as MC in an electric blue suit, looking uncannily like David Bowie circa Young Americans.

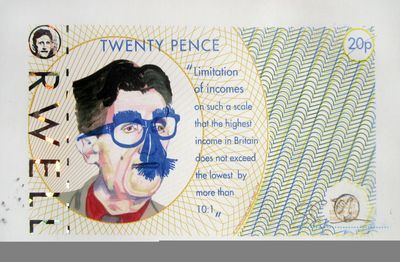

The performance combined hectic game-show silliness, satirical bite and economic critique: two "skilled" operatives used a screen print to produce banknotes (called "Orwells", pictured) which were then transferred to a conveyor belt on which they dried (operated by me turning a handle and, despite the simplicity of the task, making a complete hash of it) before being passed to the clerk for collation, stamping and signature. The Governor did nothing much. After about twenty minutes (and with motivational music blaring in the background), we assembled to find out how much ��� or how little ��� we had earned.

Each player���s ���wage��� was determined by their randomly allocated status and a spin of a wheel of fortune. We had produced low-denomination notes to the value of 1,300 Orwells. The Governor got 364 Orwells, the Clerk 182, skilled workers 109 and the rest of us 36. Our hard-earned wages could be spent on food in the hall (from "luxury exclusive oligarch gateaux" (45 Orwells) to "dull small cheese biscuits with hardly any ingredients" (20 Orwells a scoop). I bought some carrot cake, which cleared me out. Orwells could also be spent, in participating local shops and markets, on fish, eggs, bread, beer and other staples.

All this was seriously playful. Important points were made on posters and placards distributed around the venue, many of them sourced from government statistics. The people who make life in our country possible are at the bottom of the economic pile ��� cleaners and carers and child-minders and nurses and, one might add, most writers and artists. Those at the top (and I don't mean MPs on their ��74k) have mind-bogglingly high incomes ��� the average CEO of a FTSE 100 company earns ��4.6 million.

Incidentally: a large-format fine-art book entitled Money by the artist Prill Vieceli Cremers has just been published in Switzerland. Each text-free page shows a hugely magnified detail from a banknote. Most of the banknotes appear to be African or Asian, and some of them European. One is impressed not only by the astonishing virtuosity of of the engravers' techniques, but also by the range of imagery, some of it bizarre. Bridges, power stations, lumberjacks, oil rigs, bears, penguins, hippos, an orang-utan, more lumberjacks, teachers, cranes (mechanical and avian). Jet planes soar over modernist civic architecture, fishermen, bays and waterfalls. There's HM The Queen (in her younger years) and Colonel Gaddafi and Gandhi; a petrie dish, sunbathers, and a transparent grand piano . . . . This alluring volume ��� like Maximum Wage, unsettling too, in its own way ��� is published by Edition Patrick Frey, priced at ���40.

March 11, 2016

Can Europe hold together?

Camp set by migrants at the Greek-Macedonian border near the Greek village of Idomeni, on March 10, 2016. Sakis Mitrolidis/AFP/Getty Images

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Cradle of the Enlightenment. Birthplace of many wonderful writers and composers, and home to some of the finest works of art and architecture. But Europe has also been the site of innumerable religious and civil conflicts. And, of course, in the past century the continent experienced two catastrophic wars and one of the greatest crimes in history. What is now the European Union was founded in the 1950s partly in an attempt to ensure that hostilities wouldn���t break out on the continent again. It wasn���t able to prevent the non-EU member Yugoslavia from erupting into civil war in 1992���5, and the country���s consequent break-up into six sovereign states. But France and Germany have been locked together in a permanent loving embrace. Meanwhile, the eastern half of the continent effectively disappeared behind the Iron Curtain before re-emerging in the late 1980s and early 90s. Then came the euro, and the expansion of the Union, to its current membership of twenty-eight countries (minus that serial non-joiner right in the middle, Switzerland), with several more waiting to join: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia and ��� more problematically ��� Turkey.

But is the old continent now tearing itself apart in its attempts to deal with the terrible refugee crisis? The French daily Le Monde recently talked of the ���clinical death of Europe���. It���s perhaps not a surprise that countries with very different histories, levels of prosperity and political priorities should find the crisis an impossible challenge to tackle collectively. While Greece bears the all too visible burden of daily arrivals on its shores ��� the country is in danger of becoming a ���warehouse of souls��� in the words of its prime minister Alexis Tsipras ��� its northern neighbour Macedonia is currently closing its borders, as are Croatia, Serbia and even liberal Slovenia. The hardline Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orb��n ordered a barbed-wire fence to be built along its southern border last year. Both Denmark and Poland have taken a tougher stance since rightward changes of government last year. Austria and Greece, meanwhile, have traded harsh words over the crisis, and Angela Merkel has been heavily criticized at home for her generous attitude towards refugees; even Sweden is drawing back on its hitherto ultra-liberal approach. Italy, perhaps understandably, worries about the possibility of large numbers coming across the Adriatic Sea from Albania. The Schengen Agreement, which several countries signed up to in 1985 with the aim of creating a borderless Europe, now looks under serious threat. How many countries want open borders now?

On the face of it this seems a strange time ��� inopportune, even ��� for the United Kingdom to be preparing for a referendum on continued EU membership. The vote that David Cameron has called on June 23 will be a momentous event, no question. In common with many others, I wasn���t of voting age when the British people voted to stay in the European Economic Community, or Common Market as it was more commonly known, in 1975 (Britain had entered under the Conservative prime minister Edward Heath in 1973), and so will welcome the chance to have a say this time around. But, as the Guardian asked the other day, why are we having a referendum at all? Cynics might say the move is Cameron���s ploy to still rebellion within his own party (in which, lest we forget, civil war has practically broken out over Europe in the past ��� remember the beleaguered prime minister John Major���s reference to the Europhobic (���Eurosceptic��� is not a strong enough term) ���bastards��� who were making his job impossible?)

The UK has always been a difficult EU member (think of Margaret Thatcher���s battles with Brussels) The Dutch journalist Hugo de Vries wrote in De Volkskrant that ���well-meaning attempts��� to keep the British in the EU fail to take account of our ���island consciousness���. If we leave the EU, the remaining twenty-seven countries may be ���a little less rich��� but they will have got rid of ���an arrogant pain in the ass��� (!). Le Monde, meanwhile, in a recent editorial, professed itself under the impression that the British had invented the notion of clubs, and their admission rules. At the heart of the European club, it wrote, they want to retain their exceptional status ��� ���this isn���t fair play���.

���Brexit��� and ���Project Fear��� (a term coined by Boris Johnson?) have already become part of the common discourse. We will no doubt be subjected to many economic arguments for and against over the coming weeks, but most of us voters ��� let���s face it ��� will still not be able to make a properly informed decision on economic grounds alone. Personally, I���d like to hear more about how Britain can play a bigger part in tackling the refugee crisis; about how, in a globalized world, it maybe makes sense for countries to form strong alliances rather than seek to strike out on their own. It'd be interesting to know how non-European countries are likely to react to a Brexit.

March 9, 2016

Romney���s sketchy Shakespeare (and Milton)

By MICHAEL CAINES

Thomas Chatterton wasn't the only young man struggling to make a living in London in the 1760s. The painter George Romney was likewise trying to make his mark and not getting very far. Eventually, his determination paid off, however, and in later years he had to adapt his working methods in order to keep up with the demand for portraits. These were lucrative labours that came at a high personal cost: as time went on, his health suffered and he found it difficult to carry out his schemes for paintings on a grander scale, on historical and literary themes. Such ambitions mattered deeply in the art world of the time. As Norma Clarke put it in the TLS: "It is a commonplace that history painting was vaunted as the most elevated pictorial endeavour, but it might be more accurate to say that it consolidated the mythical stories the nation was telling itself".

The sketch above is one in a sequence from the early 1790s that testifies to Romney's passion for Shakespeare: it depicts the banquet scene from the third act of Macbeth (the one with Banquo's gatecrashing ghost). It also stands in, intriguingly, for the implicit finished painting itself, which Romney was never to execute . . . .

Romney's Macbeth sequence appears in the first of three sketchbooks recently put on show at Abbott and Holder, alongside his artistic ruminations on comparably elevated themes: 14 by 23 cm scenes from Paradise Lost; "The Effects of Envy and Pride for Want of Faith"; "A Shipwreck at the Cape of Good Hope"; and so on. Pretty much all of the drawings have now been sold; the first sketchbook, containing Shakespeare and Milton, going to the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC, where it will find a good home alongside similar curiosities (such as Romney's depiction of those Scottish witches in their cave). Londoners and London-bound folk can still see these "heroic drawings" at Abbott and Holder's gallery, though, if they go by March 26, and there is also this excellent online gallery for all to visit.

As the accompanying catalogue explains, Romney's banquet scene was intended as a contribution to the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery, which had opened in May 1789. This unprecedented project was supposed to create an "English School of Historical Painting", as well as enrich the publisher John Boydell, who proposed to produce prints of the paintings in the gallery as well as an illustrated edition of Shakespeare's Works. (There's a review by Claude Rawson in last week's TLS, as it happens, that gives some necessary context for the late eighteenth century's Bard fixation.)

Romney provided an allegorical vision of "The Infant Shakespeare attended by Nature and the Passions" ("Very Corregiesque", he judged it to be) and, with some difficulty, a grand view of Prospero and the shipwreck from the beginning of The Tempest, which is now lost but entirely mourned:

He also seems to have taken offence when Joshua Reynolds and Benjamin West were offered the highest possible fees and he wasn't. He had spent "over twenty-five years in creative engagement with King Lear and Macbeth", the art historian Alex Kidson has written, but offered the gallery only an elegant portrait of the young Emma Hart ��� the favourite model later better known as Nelson's mistress Lady Hamilton ��� as Cassandra in Troilus and Cressida. She is also, perhaps, the model for his Miranda, given his earlier (and more effective) little portrait of her in the role.

It is exciting to imagine that, rejecting the Reynolds-led orthodoxy, Romney's Macbeth banquet scene would have looked more like his bold "Titania and Her Attendants", one of a number he based on A Midsummer Night's Dream; this one has the Northern Lights in the background and notably seems to conform to the idea he put forward for such pictures: that they should resemble "a momentary impulse or impression in the Mind". The sketches convey a similar energy and spontaneity, although they also seem to represent another pronouncement of his: that a finished picture might be "heated and fermented long in the mind and varied every possible way to make the whole perfect". The final impression of spontaneity might be only that ��� an impression. Some thought that "Titania" was left unfinished, but the Folger also owns a preparatory sketchbook dedicated to it that contradicts that notion. There is further evidence for his literary interests and experimental tendencies in this essay by Jennifer Jones-O'Neill about another sketchbook in the National Gallery of Victoria.

I suppose there's also some continuity between the scenes Romney chooses from Shakespeare and Milton ��� here's one of his sketches of "Ithuriel and Zephon finding Satan at the Ear of Eve", from Book IV of Paradise Lost (which could also be compared with his much earlier "Ghost of Darius appearing to Atossa", inspired by Aeschylus' tragedy The Persians):

"So started up in his own shape the Fiend. / Back stept those two fair Angels half amaz'd . . .": it's easy to see why this subject should have likewise appealed to Henry Fuseli.

His problems over the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery aside, there is this interesting, darker side to Romney's imagination that sets him apart from his fellow society painters. Kidson calls him "by temperament one of the first great modernists in British art". In 2002, the bicentenary of his death, a TLS reviewer could call him "underrated" ��� is he still to be found lingering in Reynolds's vainglorious shadow?

March 8, 2016

A night with Gloria Steinem and why the Feminist Library deserves better

The Feminist Library (upstairs window)

By ROZALIND DINEEN

On a recent cold evening, Gloria Steinem was gently escorted on to the stage at the Emmanuel Centre, a listed building tucked around the corner from Westminster Abbey, the Houses of Parliament and various other institutions of hierarchy and power in central London.

Steinem draws a crowd. At eighty-one, with decades of feminist activism behind her, she has witnessed a great deal of societal change: distortions and corrections and new frustrations. The seats were sold out ��� all 1,000 of them, at ��25 a pop. And the auditorium (���completely circular and supported by 24 pairs of marble columns, with natural light flooding that [sic] through a huge glass dome and arched windows, finished off with original polished English oak panels along the walls���) was full, mostly of women ��� well-heeled women at that, with great hair and great coats.

Steinem was followed on to the stage by her interviewer Emma Watson, she of Harry Potter and also the UN ���HeForShe��� speech (���If men don���t have to be aggressive in order to be accepted, women won���t feel compelled to be submissive. If men don���t have to control, women won���t have to be controlled��� etc), who is now the face of a Feminist book club.

Here was youth beside experience: fashionable feminism beside that which has endured. Steinem was lively, bright and kind, not hardened. Yet when Watson read out a statistic from the book Sex and World Peace that she found astonishing ��� ������more lives are lost through violence against women from . . .

. . . sex-selective abortion, female infanticide, suicide, egregious maternal mortality, and other sex-linked causes than were lost during all the wars and civil strife of the twentieth century������ Steinem was calmly unsurprised. ���It has taken us thirty years to get it conceptually to most folks that rape is violence���, she pointed out. ���Men have to prove their superiority to women and other men���, but, if we release the pressure on men to be performatively ���masculine���, their life expectancy rises by five years. ���The source of all change is small groups of people supporting each other.���

Steinem also noted that just down the road from this grand auditorium, on the other side of the river, was the Feminist Library, and at that very moment a protest was taking place to save it from eviction. That protest was in fact taking place a little further downstream, outside a budget meeting at the head quarters of Southwark Council on Tooley Street.

The Feminist Library is a glorious thing. It is free, intergenerational, welcoming, housed in a few rooms, and it has been run by dedicated, professional, volunteers for forty years. Researchers and writers travel to it from around the world, but it is fruitful for the general browser too. Here you will find shelves of books grouped together on the subject of women and work, midwifery, miscarriage, violence, girls, Judaism and the female experience, lesbians, lovers, the connection between malnourishment and writing. Here is Ruth Hall���s biography of Marie Stopes; there Hannah Gavron is shelved next to Women's Work, Class and the Urban Household: A Study of Shimla, North India. And then the fiction (the famous, the forgotten) and the poetry.

In the periodicals room Shifra is beside Shrew is beside Sibyl. There's the Persian Feminist Quarterly, the Endometriosis Society Newsletter, the Pink Paper and Off Our Backs. On a recent visit I pulled out the issue of Spare Rib that came out on the day I was born, the special Black Women���s Issue.

This is a treasure trove of female concern. And the experience of being surrounded by only works of female writers, after a life of the opposite, is moving. These writers are here, you feel, in spite of the odds, and there is something comforting about standing between these shelves, as well as provoking.

But the Feminist Library is not well-heeled.

At the top of this post there's a photograph of the outside of the library, with its home-made sign in the window. Here's the entrance bell (top-right buzzer):

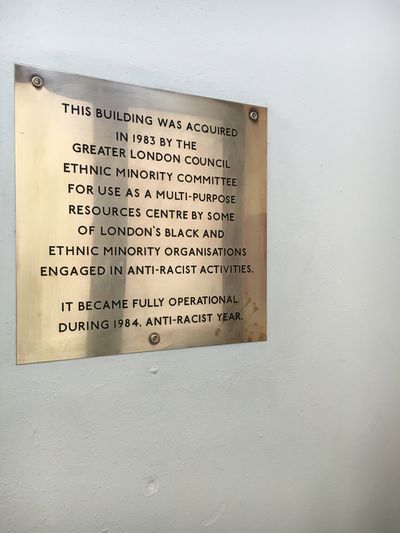

Once you gain entry, there's a plaque in the hallway:

It explains that this building on Westminster Bridge Road was originally acquired by the GLC for use by organizations engaged in anti-racist activity. Now Southwark Council, under huge budgetary pressures, we assume, have decided to re-purpose the valuable space. This is an example of that familiar London sleight of hand in which a social asset is converted into a financial one. Without fanfare the council seem to be re-purposing not just the building, but this plaque, rendering it a historical object only.

Until now the library have been charged ��12,000 a year in service charges. At the beginning of the year, Southwark Council proposed to add a rent of ��18,000 to this ��12,000. In February the Council demanded full payment or else eviction on March 1. (It would appear that the GHARWEG ��� a free training and careers centre especially for people of African origin ��� were locked out of their part of the building on February 9). Over 15,000 signatures have been added to a petition to save the library, and as a ���goodwill gesture��� the council extended the eviction deadline to April 30.

Councillor Michael Situ has been reported as saying, ���We have also given the library the time to find alternative premises, and will continue to help them find an alternative location if we can, but we are unable to subsidise their rent���.

Surely what the Councillor meant to say was that they are unable to provide many of the resources throughout the borough that they have in the past. "We are unable to subsidise their rent" makes the librarians sound like scroungers.

The Feminist Library, whether by private or public means, deserves better than this. Twenty-four pairs of marble columns, flooding natural light and polished English oak panels would be fine. But a simpler, secure future will do just as well. In 2016, feminism is hip and cool and celebrity-endorsed and yet, just across the river from those buildings of hierarchy and power, the Feminist Library makes do with a few damp rooms. On International Woman���s Day you could do worse than visit the library, sign the petition, or donate to the emergency fund and preserve this valuable resource for another forty years and more. ���The source of all change is small groups of people supporting each other.���

The office at the Feminist Library

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers