Peter Stothard's Blog, page 6

June 15, 2016

Learning to love football again

Gary Lineker celebrates after scoring against Poland in the World Cup, 1986; STAFF/AFP/Getty Images���

By STIG ABELL

Big summer football events are often as much about the past as the present. They carry with them instant access to nostalgia, a set of sights and smells immediately comparable to the previous occasions that came along with metronomic regularity every couple of years (disastrous qualifying excepted, of course).

This year, as ever, I find myself helplessly watching games in the evening, with no stake in the outcome, and feeling my fondness for the game rekindle. Because it is not that easy to love football, in my experience. And each summer tournament is a chance to love again.

I was born in 1980, in Loughborough, which sits rather glumly between Leicester and Nottingham. My dad was a Nottingham Forest fan of good standing, and had taken my mum to games when they were dating as a childhood sweethearts. My mum is perhaps the least football-friendly person imaginable: she switches off the television if anybody spits or swears on it. It���s a wonder the relationship lasted.

1980 was a glorious year for Forest. Despite being a smallish side, they retained the European Cup that year, a feat striking for the time and utterly unimaginable now. Brian Clough was the manager: Cloughie, a Midlands demi-god, adored by even non-football followers (for my gran he ranked high in the public pantheon just behind the Queen Mum and Margaret Thatcher, ahead of Charles and Diana). My first teddy bear was a giant three-foot fluffy thing called Cloughie. He came with a blanket big enough to cover me throughout my childhood whenever I lay shuddering with fever or stomach ache on the sofa. ���Cloughie���s cover��� became synonymous with getting better, with days stolen from school and the mild rigours of normal life.

Brian Clough with the European Cup trophy, 1980; Bob Thomas/Getty Images

In the 80s, I had Forest tracksuits and kits, and followed them on the extremely rare occasions they were on TV. One was the FA Cup semi-final in 1989 against Liverpool at Hillsborough. I watched it, befuddled and overwhelmed by its enormity. But it was very distant: I was nine-years-old; I had never been to a football game, and had no frame of reference for what had happened. I dimly understood death and grief, flashes of childish empathy for those who had lost someone. Hillsborough has become clearer in my mind as I got older. When I worked at the Sun, it was an ever-present issue; an indelible stain and cause for regret for everyone working there; a terrible, unforgiveable error that you cannot ever fully escape.

The first international competition I can remember is the Mexico World Cup of 1986. It was exotic and splendid, and I prepared for it with a sort of exam-like diligence. I remember my sticker collection, swapping Gary Stevens for Karl-Heinz Rummenigge with my brother, studying the players whose names I was hearing for the first time. The greatness of Gary Lineker: his legs tanned by the searing sun, unencumbered by the gleaming cast on his arm. I recall his hat-trick against Poland: three snatched, short-range strikes before he loped off languidly raising his arm. A poacher, as the commentators said, a noble thief of goals.

The vicious injustice of Maradona���s Hand of God ��� which knocked England out ��� lingers still. In some sense, it was a healthful lesson that the adult world ��� hitherto a world of brisk rules and order ��� could be deeply unfair. He cheated, and was rewarded. Perhaps healthful is not the right word, but significant nonetheless.

And, of course, heroic failure then became the keynote of English football, and of the English character more generally. In 1990, for our semi-final loss to Germany on penalties, I was ten and allowed to stay up late, carried along by adoration of the team and its potential (Lineker somehow still boyishly heroic; Gazza; the rugged imperturbability of Terry Butcher). Until that point, the pixel-sharp moment of the tournament was David Platt (a subsequent, and typically enfeebled, manager of Forest in the 90s) scoring a volley, over his shoulder, of impossible beauty against Belgium in extra time.

It is easy to embellish the memory in retrospect, and I am tempted to recall the sensations: the sticky stuffiness of the summer night, the rare lateness of the hour, the sour smell of takeaway pizza gone cold on the table, the sickly sweetness of "Nessun Dorma" through which the BBC brilliantly soundtracked that summer. But I do remember my older brother crying when Chris Waddle���s muffed penalty soared skywards (it���s probably rising still). And the sense of national unity in our collective despair: I was part of something big, even as it was terribly sad. In truth, I clung perversely to the failure, in the way a child clings to the heroism of a scraped knee or the bloom of a bruise. Failure was somehow braver than success, more credible.

Which is lucky, because six years later we were to taste glorious failure once more in Euro 96. I was sixteen, and it was a summer of girls, alcopops, guitar music and Chris Evans. On Friday nights, my friends and I would cluster in the beer gardens of Loughborough pubs with a relaxed policy on underage drinking (The White Hart; the Barley Mow), smoking cheap fags and getting excited about the football.

That year, we had a team of talent and possible inspiration. Gazza scored the wonder goal against Scotland; we beat Holland 4-1 (condemning Scotland to exit the tournament, thanks to that conceded goal; an added bonus), daring to be exciting rather than clinging to victory by narrow margins. And then against Spain, we achieved penalty redemption: Stuart Pearce, the Nottingham Forest electrician-turned-enforcer, epitomised the sense of national pluck and fight with his delirious, maniacal celebration after his potted penalty. Of course, defeat (via penalties again; against Germany again) followed, with its amorous sting of self-pity. And the last great national effort in major tournaments subsided, to remain dormant ever since.

In my teens, I had drifted towards rugby (Leicester being the other sporting lodestone of the area), attracted by its more honest physicality and more admirable need for bravery and strength. I went to see the Tigers with my whole family: grandparents wrapped in rugs passing to me, even as a young teenager, the hip-flask at half-time (me wincing as I pretended to enjoy the fiery splash of whisky); my brother and my mum and dad. Fights on the rugby pitch tended to be as decently ordered as eighteenth-century duels: face-to-face, equal, and forgotten afterwards once honour was satisfied. Football by then was already prima donnaish: all sculpted haircuts, and rolling theatrically on the grass.

My brother, however, maintained the family tradition of being a proper football fan. He left the genteel world of rugby to become a Forest season-ticket holder again. When he could drive, he would sometimes take me with him. The atmosphere was always exciting, verging on unpleasant. One game, the visiting manager had just been cleared of sexual assault charges. For the whole ninety minutes, our section of the crowd (some with children perched precariously on shoulders, or held with clammy hands) called him a ���fucking paedophile���.

Stuart Pearce had another formative role to play in my footballing experience. Every game, he would run out to the Trent End (where my brother and I stood), and grimace aggressively, his hands aloft to the crowd. We would chant in reply: ���Psycho, Psycho, Psycho!��� One game, the crowd surged in a sort of angry ecstasy to meet him, propelling me forward to the steel barrier. I reached out, and immediately the weight of hundreds of people pushed me against it, telescoping my arm back on itself. I fell to the floor, my right arm now somehow six inches shorter than my left, dizzy with shock.

I was rescued by a huge, barrel-bellied man, who spotted what had happened, bulldozed a path to me, then carried me out. (This was the second occasion I had been saved by a football fan: I was once lying prostrate on the floor in a Loughborough park, being repeatedly kicked in the head by a group of people who thought I had been speaking to a girl without their consent; and an unknown hero in a Klinsmann Tottenham top swatted them away). As I quivered on the steps outside, awaiting the ambulance, the stadium shook with cheers for an early goal. My brother, a little reluctantly, escorted me to hospital, and Forest won 2���1.

After that, my interest in the sport waned. Forest entered a dispiriting spiral of incompetence and financial mismanagement from which they have not recovered. The England team became a group of unlikeable, filthy rich underachievers, seemingly incapable of consistent effort or performance. I recall the Sisyphean arguments about whether Lampard or Gerrard could play alongside one another; by the time that subsided an entire footballing generation had passed with nothing to show for it.

So, I approach the latest European Championships, laden with memories and scepticism. Any aspiration is further knocked by the vivid pictures of misbehaving England fans, angry and shirtless, whether provoked or not.

From Belgium v Italy, June 13, 2016; Jimmy Bolcina/Photonews via Getty Images

But then the thrill of summer nights of football returns. Italy surprising Belgium, with their team spirit, hipsterish grace, and passion. An orchestra against a bunch of frustrated soloists. Ireland nearly shocking Sweden; their fans singing Abba together outside the stadium. Iceland drawing with the dilettante Portuguese, accompanied by the brilliantly guttural "ooom" chanting that seems to rise up from a saga (my favourite fact of the championships: around 10% of all Icelandic people are in France supporting their team). England picking a young team of hungry players, free from too much expectation.

It might be nothing, but it might be a love being reborn. After all, Leicester (the wrong Midlands team, but there you go) won the Premiership this year, so anything is possible.

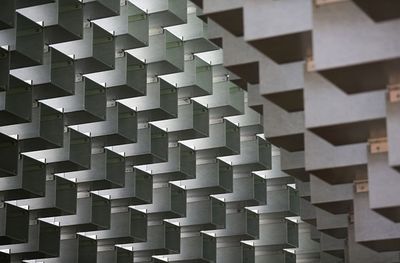

Bjarke Ingels's Serpentine Pavilion

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

Big is the defining word of this year���s Serpentine Pavilion. It���s designed by BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group, the newest starchitects-on-the-block), and its aerial-like pointed roof soars to the sky. By taking a simple object ��� a fibreglass hollow ���brick��� ��� and repeatedly stacking it on a huge scale, Bjarke Ingels has made a structure that, from one angle, is a wall full of holes through which you can see the greenery of Kensington Gardens, framed multiple times over. Move around it, though, and the pavilion turns into what looks like the cross-section of a twisting iceberg.

Once inside, however, it���s ��� strangely ��� not that big. A gaping-mouth entrance, which looks back at the Serpentine Gallery, perfectly framing its bell tower, becomes a narrow cave with hypnotic square walls that close in on you. Its proportions are a little uncomfortable. Sitting at its widest part, on a beautiful Douglas fir bench, I felt like I was in a compact thoroughfare. There���s something reminiscent here, too, of the exteriors of high-density buildings (no surprise, since Ingels designs quite a few of these), especially in Hong Kong, where basic forms are satisfyingly repeated, yet can make you feel both uneasy and overwhelmed.

Serpentine Pavilion, 2016. Photo: Daniel Leal-Olivas/AFP/Getty Images

Serpentine Pavilion, 2016. Photo: Daniel Leal-Olivas/AFP/Getty Images

High-rise flats in Kowloon district, Hong Kong. Photo: Agencja Fotograficzna Caro/Alamy

High-rise flats in Kowloon district, Hong Kong. Photo: Agencja Fotograficzna Caro/Alamy

���Think about computer programming���, Ingels said to us last week at the opening talk (the Pavilion runs until October 9). ���A maximum amount of information is made from the minimum amount of coding. You condense meaning into as few moves as possible . . . to get the extraordinary out of the ordinary.��� Modesty, as you can hear, is not associated with BIG. But perhaps the valiant is. Their power plant in Copenhagen, expected to be completed next year, will feature an alpine ski slope ��� the first one in Denmark ��� on its roof. Ingels wants to reconfigure our perception of what such a utilitarian building might be today; with clean emissions, why not make it double up as something else the public can use and enjoy? Another project ��� a flood and storm barrier in Manhattan ��� will be disguised as a park.

Serpentine Pavilion, 2016. Photo: Daniel Leal-Olivas/AFP/Getty Images

Serpentine Pavilion, 2016. Photo: Daniel Leal-Olivas/AFP/Getty Images

���We take human happiness very seriously���, he tells us. ���Yet there���s never any irony in our work . . . we say what we mean.��� There���s something refreshing about that. And about the joyful spirit with which he approaches his projects, even if, in reality, they are not always subtle or wholly sensitive to their surroundings. This year���s Pavilion might appear similar to Sou Foujimoto���s in 2013 ��� riffing on cube shapes ��� but Ingels���s doesn���t have the same finesse. Nonetheless, he taps into the Serpentine���s aim to make architecture playful and accessible, something that enables and accommodates our lives. Anyone can walk into it (free admission) or climb on it (though there is a metal line half-way up the structure marking where you can���t go beyond). This is architecture as communal experience.

And the Pavilion project itself has grown bigger since last year. As well as Ingels���s Pavilion, there are now, for the first time, four small ���Summer Houses��� on the other side of the Gallery, deeper into Kensington Gardens. One, designed by Kunl�� Adeyemi (above), is a replica of the inside of the Queen Caroline Temple which sits opposite. Asif Khan���s is made from horizontal curving white bars that reflect the sun and act as a sundial. They are not as impressive or as slickly finished as the main Pavilion, but there���s no harm in celebrating, and pushing, the possibilities of architecture, and what it can mean to each of us.

June 14, 2016

The little-known Maeve Gilmore ��� artist (and wife of Mervyn Peake)

Mervyn Peake sketches his wife Maeve Gilmore as she works at her easel, 1938; �� General Photographic Agency/Getty Images

By GEORGE WASHBOURN

Some six months ago, I received an unexpected email from the Mervyn Peake Estate, offering me work. I had been referred to them by my university department. The Estate was searching for an archivist to produce a comprehensive inventory for galleries of all of Peake���s work. Flattered, intrigued and, crucially, in need of money, I accepted . . . .

The walls of the Peake household in north London are proudly flanked with the artist���s work. Proudest of all is a huge portrait of the man himself, which hangs at the top of the stairs, his tousled brown hair, red flannel shirt and arsenal of paintbrushes and pots compounding his bohemian image. And yet, this portrait was not, I discovered, a self-portrait ��� it was painted by Peake���s editor, biographer and wife Maeve Gilmore, a woman about whom I knew next to nothing and whose work I was also charged with logging.

Maeve met Mervyn on her first day at Westminster School of Art, where, at the age of seventeen, she was studying to become a sculptor. Mervyn, six years her senior, was already a successful painter by this time, teaching at the school to supplement his income. Dazzled by what she described in A World Away: A memoir of Mervyn Peake (1970) , as his ���native exuberance��� Maeve agreed to go to tea with him. They were married a year later and stayed together until Mervyn���s death from Parkinson���s, thirty years later, at the age of fifty-seven.

For much of their marriage, they made a home on the Channel island of Sark, in a large white chalet, previously the headquarters for the German occupied forces; from the get go, a firm dynamic was established, with Maeve devoting herself to her dark and intriguing husband and their three children.

But as Mervyn���s career burgeoned with commission after commission, Maeve quietly continued to paint; her output over the years was prolific, matched only by that of her husband. So far in my inventory I have logged more than 200 paintings, with many more to go.

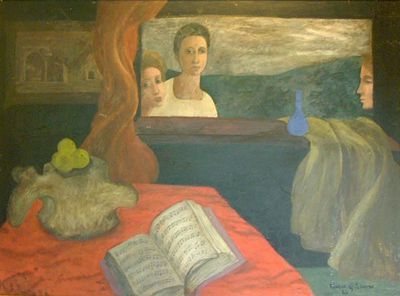

An oil painting by Gilmore, 1940, depicting music and a vertibra from a beached whale found by Mervyn; �� The Mervyn Peake Estate.

There are considerable riches here, ranging from portraits and scenes of pastoral Sarkese life to her later, more abstract and surrealist experiments. Earlier paintings of her children, playing in the garden and wearing fancy dress, give way to a series of anonymous portraits ��� featureless white figures, with unusually long frames set against starkly coloured backgrounds, seem to stare at the viewer. Another painting ��� perhaps the most poignant of them all ��� was painted soon after her husband���s death and, like most of her work, has never been seen outside of the family home, let alone exhibited. A messianic figure with the unmistakable dark and sallow eyes of Mervyn Peake is strung up on a crucifix; the canvas is splattered with red.

Today would have been Maeve Gilmore���s ninety-ninth birthday, and it would be good to say that her love and devotion to art continues through our own appreciation of her work. Sadly, it is not so. Type her name into a search engine and you���ll struggle to find anything showcasing solely her work; she is lost among myriad links to Mervyn Peake and his own impressive work. Of course, among artists or otherwise, such an eclipse is not an uncommon hazard of marriage ��� how long a list might one compile? ��� but if, with this short blog, we can add one more link to Maeve Gilmore and her work, so much the better: she���s long overdue a bit of attention.

June 13, 2016

The poetic riches of the Gerald N. Wachs collection

By WILLIAM BAKER

More than a decade ago, I bid for a Tom Stoppard item online. The price went higher and higher ��� outrageously so for a reprint of a play not all that scarce or expensive in its first edition. In the end, I was outbid. Afterwards, I was surprised to receive an email from a Dr Gerald N. Wachs in New York City asking why I was prepared to pay so much. I explained that I was a Stoppard collector and was compiling his bibliographical history. Immediately, Wachs responded that I was most welcome to come to see his own Stoppard collection. So I landed up in his flat overlooking the Met, where I subsequently spent many happy weeks working on Stoppard, and sleeping amid signed copies of the great English romantic poets, among other treasures.

Jerry was an avid collector, but the nineteenth-century first editions of English poetry were the cream of his collection. This element he built up with his friend, the eminent bookseller and bibliographer Steve Weissman, then of Ximenes Rare Books. They began in March 1970, and continued until Jerry���s death in 2013 at the age of seventy-six. They collected only the finest copies ��� presentation copies to other writers, friends, family members; and 155 of them will be for sale at the first session of Sotheby���s ���Fine Books & Manuscripts��� auction in New York tomorrow.

There is, as I had expected, much to choose from. The first item is a presentation copy inscribed on its front wrapper by Matthew Arnold to a fellow pupil at Rugby, Edward Armitage. Only one other inscribed copy of Arnold���s extremely rare first published work, Alaric at Rome (1840), is known to exist. The estimates range from US $45,000 to $65,000. Also for sale is Arnold���s Merope: A Tragedy (1858) in the original green cloth stamped in blind and inscribed by Arnold on its half-title to his father-in-law ($2,000���$3,000).

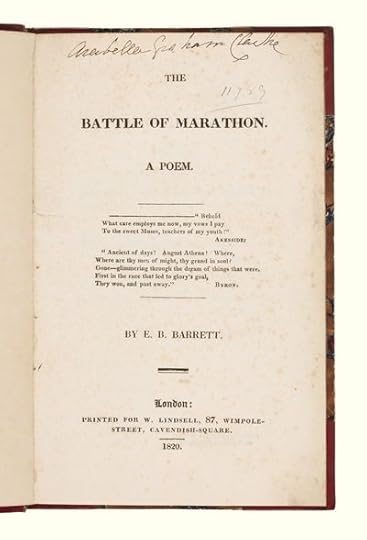

Other items include the Bront��s��� Poems (1846), the rare first issue of their first book in the original cloth ($15,000���$25,000) and its second issue with the errata slip ($2,000���$3000). There is the first edition of Elizabeth Barrett Browning���s first book, The Battle of Marathon (1820). The copy has twenty-four punctuation corrections additional to those known to exist; only fifteen copies are recorded, all in private hands ($80,000���$120,000).

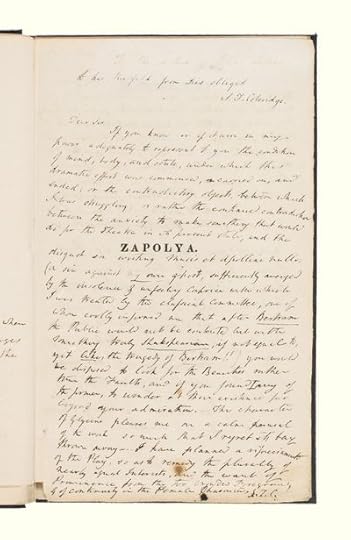

Samuel Taylor Coleridge items include the first edition of his first book, The Fall of Robespierre (1794) with the proposal leaf present ($8,000���$12,000). Perhaps the most interesting item from a scholarly point of view is that of Zapolya (1817). This is an extraordinary presentation copy, inscribed by Coleridge on its half-title in the form of a lengthy letter to John Gibson Lockhart (1794���1854). The estimate appears to be on the low side at $12,000���$18,000.

Keats is represented by his first volume of poetry ($15,000���$25,000); a first edition first issue of Endymion ($4,000���$6,000); Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St Agnes and Other Poems (1820; $6,000���$8,000); and the sixty-three issues of The Chambers: A London weekly journal that contain the poet���s ���The Sea��� and his reviews of three dramas, the sole prose he apparently published during his lifetime ($10,000���$15,000). The Keats collector will also not wish to miss the five volumes of Annals of the Arts (1817���20), containing the initial anonymous publication of Keats's odes ���To a Nightingale" and ���Grecian Urn��� and his two Elgin Marbles sonnets ($8,000���$12,000).

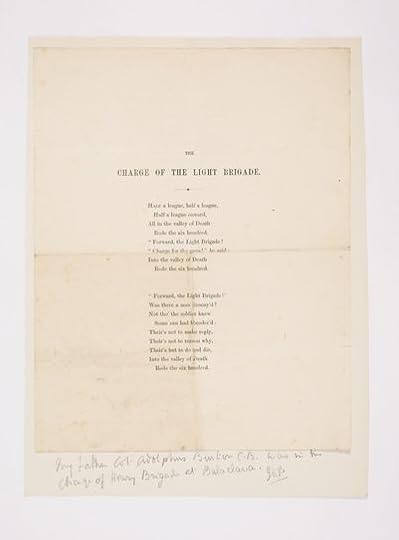

The Shelleys include a first edition of Mary Wollstonecraft���s Valperga (1823; $6,000���$9,000), followed by sixteen Percy Bysshe Shelleys. The Tennysons are extensive, too, one highlight being The lover���s tale (1833; $8,000���12,000), described in the Sotheby���s catalogue as ���one of the great rarities of nineteenth century English literature���. The other highlight is the first separate edition of ���The Charge of the Light Brigade��� (1855; $25,000���$35,000) ��� the copy that apparently went to an officer in charge of the Heavy Brigade at Balaclava.

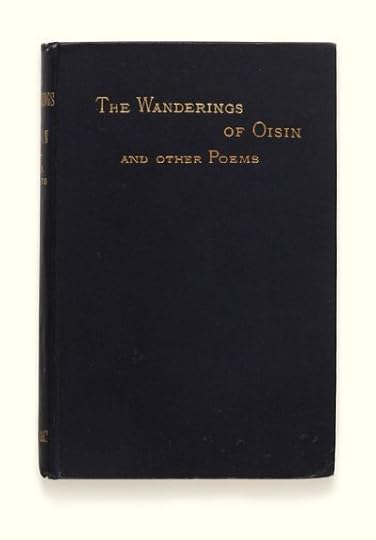

Unsurprisingly, there is a run of Wordworths and Wordsworthiana. The highlights include the first edition of his first book, An Evening Walk ($50,000���$70,000) with its errata leaf; his second book Descriptive Sketches in Verse ($40,000���$60,000) with the A2 errata leaf present; and a copy of an unrecorded Wordsworth broadside ��� "an address to the freeholders of the county of Westmorland" ��� dated January 30, 1818: the estimate is between $25,000 and $35,000.The final item in this sale of infinite riches from the Wachs collection is a first edition in the original cloth of Yeats���s The Wanderings of Oisin (1889; $2,000���$3,000).

It baffles the mind to think that I shared a room with these greats. Did I not also turn the pages of Aubrey De Vere���s The Search after Proserpine (1843), fascinated by Walter Savage Landor���s extensive annotations? (This volume is not mentioned in the sale.) I spent time, too, with Landor���s Heroic Idylls, a proof copy extensively annotated by Landor and dedicated to Edward Twisleton, to whom he had been introduced by Robert Browning. Landor inscribes the book, ���All my old friends are dead, let their place continue to be supplied by Edward Twisleton���. The copy has more than fifty new lines of verse in Landor���s hand, and spelling and punctuation alterations on almost every page. It is estimated at $3,000���$4,000; like its poet, one can only dream on.

June 10, 2016

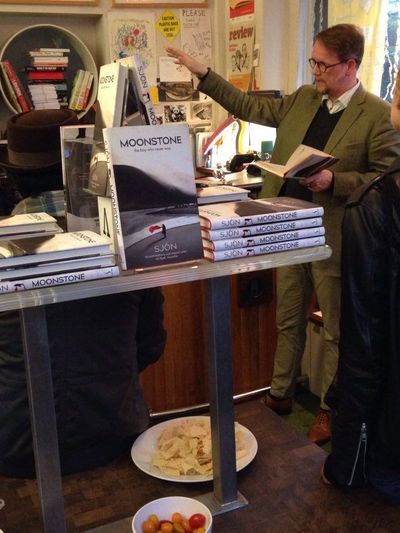

Sj��n at Review bookshop

By FR����A ��SBERG

On June 2, another book by the Icelandic author Sj��n was published in English: Moonstone: The boy who never was (M��nasteinn: Drengurinn sem aldrei var til), translated by Victoria Cribb. This short semi-historical novel won the Icelandic Literary Prize for Fiction in 2013. Some time ago, Sj��n met a friend in Hong Kong, a Londoner who told him that if he ever did anything literary in the UK he would have to do it in Review ��� a lovely small independent bookshop in Peckham. So there we were, an audience of fifteen, Sj��n by the counter and Katia, the bookshop manager, smiling from ear to ear behind it.

Before discussing and reading from the book, Sj��n told us briefly about his working methods and where he came from as an author. Bored in suburban Reykjav��k, the fifteen-year-old Sj��n, along with seven other boys, formed Med��sa ��� a surrealist movement inflamed by Andr�� Breton���s writings and manifesto. It was then that he took up his pen name, Sj��n, meaning ���vision��� in Icelandic, and an abbreviation of his forename Sigurj��n. The goal was to mount a surrealist invasion of Reykjav��k, and Sj��n said jokingly that in some sense they succeeded ��� nowadays ���surreal��� is such a common adjective that it even finds its way into speeches in the Icelandic Parliament.

Sj��n is a hoarder who gathers information about random subjects ��� at the moment he is preoccupied with gorilla actors from 1930s Hollywood films, and every detail he comes across is safely filed. This is how he gradually maps the themes of his stories. Before writing the story of M��ni Steinn, Moonstone's main character, he had for some time been collecting information on three topics: the Spanish influenza in 1918, Reykjav��k's history of cinema, and homosexuality in Iceland and the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s. Sj��n searched for a protagonist to fit those themes, first trying out a teenage Don Juan in 1920s Reykjav��k ��� but while reading Neel Mukherjee���s A Life Apart (2010), whose main character is homosexual, he realized that M��ni was also gay. So there he had a dynamic to work from. ���What do you not do during an epidemic?���, he asked us. ���Have sex with strangers.��� Although AIDS never comes into direct contact with the storyline, Sj��n explained, the story is very much about AIDS, and dedicated to the memory of his uncle B��si, who died of AIDS in 1993.

Sj��n was clearly happy with Victoria Cribb���s translation, warmly praising its precision, and when he was asked whether he felt that anything might be lost in translation, he answered: ���if anything, I���m just worried that the translation is better than the original���.

Moonstone will be reviewed in a forthcoming issue of the TLS.

June 9, 2016

Up in smoke

By GEORGE BERRIDGE

A short stroll from Hyde Park Corner will take you past two buildings that stand as reminders of some of the darkest days in the story of Lord Byron.

At 139 Piccadilly, you���ll find the Georgian mansion that for a short time served as home to his botched marriage to Annabella Millbanke.

If you walk for ten minutes down the road and take a sharp left, you���ll arrive at 50 Albemarle Street (see picture above), the house where, as Corin Throsby notes in her review of The Burning of Byron���s Memoirs, the ���greatest crime in literary history��� took place, perpetrated by the poet Thomas Moore, Byron���s publisher John Murray (whose name remains outside the house and on a brass plaque on the door) and his old university friend John Cam Hobhouse.

As one looks up at the chimney from which issued forth the charred pages, it feels like a good moment to reflect on writings that suffered the same fate, and those that avoided it ��� for better or for worse.

While Byron never intended for his work to go up in smoke, there are a number of writers who ��� for various reasons and to varying degrees of success ��� hoped for just that.

Gogol destroyed the second part of Dead Souls (intended as homage to Dante���s Purgatory) as part of a later-life obsession with Orthodoxy and Asceticism. Gerard Manley Hopkins, similarly, burned most of his poetry upon entering the priesthood.

Bulgakov torched the first copy of The Master and Margarita in 1930 for fear that he could not be a Soviet Writer. He (more or less) finished the novel in 1940, although an uncensored version didn���t appear until the seventies. As the quick-witted cat Behemoth tells us: ���Manuscripts don���t burn���. It���s a good thing for this jobbing hack that he was more figurative than literal, else this blog might be cut sh

To Kafka, then! The Castle, The Man Who Disappeared and The Trial only survived, after the author���s death at the age of forty, thanks to the disobedience of his dear friend and literary executor Max Brod. Kafka expressly told Brod that his work should be burned.

A sickly R. L. Stevenson ��� who almost killed himself writing the first version of Jekyll and Hyde ��� was so distressed by a questioning note from his wife and editor Fanny that he is said to have burned the pages of his manuscript in his room. Against all odds, rewriting the novella seems to have aided his convalescence (along with a few sharpeners, if some reports are to be believed) and he was bolstered in a number of weeks.

Lovers of literature owe an enormous debt not just to writers but also to their literary executors, ranging from Plotius and Lucius, saviours of the Aeneid (on which more shortly) to the indefatigable Robbie Ross, who rounded up the rights to the works of Oscar Wilde which had been sold off after he went broke.

I���ve been left chewing over the ethical question that faced a number of them: what duty is there to honour the dying wishes of authors? Should merit and significance be allowed to trump those wishes?

Have we been left bereft by the burning of Larkin���s diaries? (���[I am] rather depressed by the remorseless scrutiny of one���s private affairs that seems to be the fate of the newly dead. Really, one should burn everything.���) Of Saki���s? Of de Sade���s final manuscripts?

Consider two cases: Virgil and Nabokov. Virgil ��� who hauntingly describes the vanishing world and culture of Troy in Book II of the Aeneid, wreathed in flames ��� wished that the unedited copy of his work be turned to ash. Yet, on the orders of Augustus, who had been read sections, the poet���s final wishes were disregarded ��� and so we possess what was spared from the fires.

It is largely agreed that the original version isn���t too far from the final manuscript. So was it really not worth publishing? Should we indulge the often neurotic self-criticism of writers, or print and be damned?

Nabokov���s son, Dmitri ��� aware of the guilt-wracked Mr Moore? ��� argued prior to the publication of The Original of Laura: A Novel in Fragments, that "I wouldn't have wanted to go down in history as a literary arsonist".

This paper���s Editor, Stig Abell, agreed in his review of the book in 2009: ���Books are made to be read, not destroyed. And the work of epochal artists should be preserved and made public. The burning question is not, in the end, much of a burning question���.

Not all have been so forgiving. The Guardian took the critical line that money and fame might have been more important to the son than preserving his father���s legacy. This question of legacy ��� preserving or damaging it ��� brings to mind David Foster Wallace���s The Pale King. While it shows signs of brilliance, there is no getting around its sombre and often frustrating incompleteness (something discussed at greater length in Robert Potts���s review in April 2011).

Having concluded my walk at the big Waterstones just down the street, I sat in the shop���s caf��, surrounded by Kindles and other e-readers, I���m also left wondering if the romantic final orders of the above would be given today. Will the tradition survive in an age of USBs? ���Please, darling, have my hard-drives wiped��� doesn���t quite have the same impact, does it?

June 7, 2016

Eureka momentum

By MICHAEL CAINES

The Savoy Hotel hosted the 20th South Bank Sky Arts Awards on Sunday night; alongside the actors, comedians, musicians and other artists honoured this time round, Sunjeev Sahota received the literature award, for his well-regarded novel The Year of the Runaways. It's a notable choice on the (anomalously anonymous) judges' part. It's very much a novel of its moment, describing the lives of Indian illegal immigrants in Sheffield, including two posing as a married couple. Yet its prose is also the least enticing of the three short-list books ��� all of them novels, although the award in theory covers all genres ��� efficient but strangely plain, despite the colourful Hindi insults.

Nothing wrong with that, perhaps. But I prefer the work of Sahota's fellow short-listed novelists, Tessa Hadley and Sarah Hall. And not only because I had the pleasure of interviewing both of them last week. . . .

I do frankly, gushingly admit that the chatting about fiction really was a pleasure ��� at least for me. That's because, however, I'm already an admirer of the work ��� in Sarah Hall's case, since I wrote a gauche review of her second novel, The Electric Michelangelo, over a decade ago.

Apart from anything else, both Hall and Hadley are writers of books that many readers seem to relish for the kinds of stories they tell ��� but also for the sheer cumulative power, and the distinctive textures, of their prose. Here, for example, is how Hall's nominated novel The Wolf Border conjures up a dream encounter between its protagonist Rachel and one of the beasts of its title:

"It comes between the bushes, as if bidden. It comes forward, mercilessly, towards her, paws lifting, fast, but not running. A word she will soon learn: lope. It is perfectly made: long legs, sheer chest, dressed for coldness in wraps of grey fur. It comes close to the wire and stands looking at her, eyes level, pure yellow gaze. Long nose, the black tip twitching, short mane. A dog before dogs were invented. The god of all dogs. It is a creature so fine, she can hardly comprehend it. But it recognizes her. It has seen and smelled animals like her for two million years. It stands looking. Yellow eyes, black-ringed. Its thoughts nameless. . . ."

And here is Harriet, one of the four siblings at the heart of Hadley's novel The Past, in another encounter with beautiful yet disquieting nature:

"On her way home from birdwatching Harriet crossed a tussocky field, a narrow wedge shape between two stretches of woodland, rising steeply to where it was closed in by more woods at the top. After the woods with their equivocal shade, the strong sunlight was startling when the path opened onto this gap; a red kite ambled in the sky above, small birds scuffled in the undergrowth, too hot to sing, and a pigeon broke out from the trees with a wooden clatter of wing beats. A stream ran down the field, bisecting it, conversing urgently with itself, its cleft bitten disproportionately deep into the stony ground and marked against the field���s rough grass by the tangle of brambles that grew luxuriantly all along it, profuse as fur, still showing a few late white flowers limp like damp tissue, and heavy with berries too sour and green to pick yet, humming with flies. . . . she wanted to taste it but thought that wasn���t sensible ��� who knew what pesticides they used on these fields? On her solitary walks she was ambushed occasionally by this fear of accidents: what if she fell, and no one knew where she was?"

I won't bang on about these two novels' other good qualities here (I've saved most of that for the friends who happen to have my copies foisted on them). I'll just note instead that our TLS Voices interview quickly gets onto a more generally curious aspect of the writing process: those moments of inspiration that can shift a story out of its intended course.

Plans change, that is, in sudden ways ��� The Past benefited from one that came to Hadley, in true Archimedes style, in the bath ��� but tend to be preceded, as she notes, by "weeks of murkiness". Novels may be "huge, sometimes planned, often times unwieldy things", Hall agrees; but "there are these great moments that occur to you that turn the direction of the book". The writer has to "embrace and cherish" these moments. (A certain well-worn line of Thomas Edison's, about perspiration and inspiration, is coming to mind.)

"A book comes in fits and jerks", John Steinbeck once observed. George Eliot and her famous deviation from the plan in Middlemarch aside, there must be many unrecorded eureka moments scattered throughout the history of the novel, propelling it on in abrupt creative bursts. Not just originary moments of inspiration, that is, but moments that upset the scheme derived from that first moment. It must be a relief to the writer who finally has one, as Sarah Hall says, after worrying weeks of "murkiness".

The South Bank Sky Arts Awards ceremony will be broadcast tomorrow night, at 8pm, on Sky Arts.

June 6, 2016

Svetlana Alexievich at the Cambridge Union

Svetlana Alexievich at the 2015 Nobel Prize award ceremony in Stockholm, December 10, 2015; credit: Reuters/Marcus Ericsson/TT News Agency

By RUTH SCURR

May 31 was Nobel Laureate Svetlana Alexievich���s 68th birthday. She spent the evening in conversation with novelist James Meek in Cambridge at a sold-out event organized by Cambridge Literary Festival and English PEN. Afterwards the queue for her books ��� Second-Hand Time, first published in English last month with extracts featured in the TLS, and Chernobyl Prayer ��� filled three corridors and spilled out onto the street.

It is thirty years since the Chernobyl disaster. Meek began by asking Alexievich (who spoke through the excellent translator Marsha Karp) about memory. ���Memory is a creature that is alive . . . nobody has simple relations with memory���, she said. Alexievich���s work is like a tapestry or collage assembled from other people���s memories and testimonials. ���I don���t do interviews���, she insists when questioned about her technique. ���I have conversations . . . the person must be interested in me . . . I must ask interesting questions and be prepared to answer questions myself.���

���But let���s be very concrete���, she said, and gave the audience an example from Chernobyl Prayer. Alexievich went to talk to a woman whose husband was dying from cancer caused by Chernobyl. He was continually screaming in pain. The woman told Alexievich that the only time he stopped screaming was in the night, when he would clap his hands and she went to him to make love. She said ���that is the only medicine I can give him, but don���t put that in your book, or people will think I���m a pervert���. Alexievich did include the story, but changed the names. Then the woman rang her up and said, ���Why did you change the names? I suffered so much and he suffered so much, so let our names be there���.

Alexievich never speaks about Communism with contempt. Her Belarusian father was a schoolteacher and remained a Communist in his nineties. Her mother was Ukrainian. She was born in Ukraine in 1948 and grew up in Belarus. Questioned about her relationship with the Russian language, she quotes a recent protester in Ukraine: ���I want to be invaded by Pushkin, not Putin���.

Reflecting on her own life and the lost promise of the Perestroika years, Alexievich is darkly humorous. ���I remember it was wonderful when we were running around squares shouting, ���Freedom, freedom!��� But then we went home and we didn���t understand what freedom was.��� Looking back, she thinks the real question of that era was: ���Ok, so you���ve been reading Hegel, but can you be a businessman?��� She remembers the books of Akhmatova and Solzhenitsyn ��� for circulating which people had been prepared to risk punishment under the old authoritarian regime ��� suddenly lying around for sale in the street, but no one was interested in reading them any more; there was as much pleasure to be had from a new coffee machine as from books. (���Welcome to the West���, said Meek.)

���Some people think consumerism saved us from civil war���, Alexievich remarked. (���Well there���s at least one PhD in that���, quipped Meek.) Then she summoned up a haunting image of what the future might be like. She described visiting one of the abandoned villages near Chernobyl, where wild beasts now inhabit the deserted houses, but a statue of Lenin still stands with his arm outstretched over the desolate scene. ���Of course we need a new philosophy of life���, she said, ���but then everybody wants to have two cars in the household.��� And the well-heeled audience laughed nervously.

On May 30, Svetlana Alexievich gave the Elliott Lecture at St Antony���s College Oxford. Her title was ���The history of the Russian-Soviet soul���, and the convener was the TLS Russia and East-Central Europe editor Oliver Ready. A recording of the lecture is available via TLS Voices:

June 5, 2016

Britain, please leave!

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Still undecided with less than three weeks to go before the referendum? This might help. They ��� the Europeans ��� want us to leave! They���ve had enough of us. And, frankly, who can blame them?

That ��� at least ��� is the point of view of the French daily Lib��ration���s Jean Quatremer: although he says at the outset that it���s not really in our interest to leave, if we stay in we will make life sour for them like never before, and the ailing project, buffeted by nationalist winds from the East, will be done for: "David Cameron will be the only European leader to have won a referendum on Europe and will therefore have a central role in the Community game. He and his successors will then negotiate concession after concession and thereby bury entirely the federalist dream of the European fathers and complete the Old Continent's transformation into an ever slacker free-exchange zone". Therefore, for the sake of the EU, we are politely being asked to clear off.

Quatremer suggests that our sacrifice for the sake of the European common good would have an element of greatness even if, as he concedes, it could well lead to the break-up of the UK. He reminds us ��� and this should warm the hearts of all Brexiteers ��� that it would be the fourth time that Britain has come to the aid of divided European tribes, after the fight against the French empire (the unnamed Napoleon) and two German Reichs, with huge sacrifices.

He ends, resoundingly: ���Come on, British friends, a bit of courage! Allow yourselves to be convinced by the brilliant leaders Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson who, deep down, have only Europeans��� interests at heart".

And in twenty years��� time, he promises, they will let us back in. What could be better I say!

For a different perspective see this week���s TLS symposium, and the heartfelt plea on this week���s Letters page for us to remain.

June 2, 2016

On Cockatoo Island

"Room of Rhythms", 2016, by Cevdet Erek. Photograph: Ben Symons

"Room of Rhythms", 2016, by Cevdet Erek. Photograph: Ben Symons

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

On holiday in Australia recently, one of the most bizarre places I came across was Cockatoo Island. It���s a UNESCO world heritage site in the middle of Sydney Harbour and, until Sunday, the host of Sydney���s twentieth art biennale. Before all this, though, it has had an extraordinary past.

Named after its sulphur-crested inhabitants, Cockatoo Island has, since 1839, been a prison for particularly bad convicts; an Industrial School for Girls, which took over the same prison buildings (you can still see crumbling-brick cells, ceramic sinks, faded tiles and childlike scribbles on the walls ��� imagine what it must have been like for those school children); and a ship-building yard, at its peak during the Second World War. The island then lay dormant for a decade in the 1990s, underwent restoration from 2001, and was opened to the public in 2007. There are camping areas now, too. (I���m not quite sold on that idea.)

Huge warehouses, surrounded by an array of spectacular industrial cranes, provide the main venues for the art work at this year's biennale ��� which is a mixed bag, not helped by the airport-style barriers (everywhere) with A4-paper signs telling you where you shouldn���t stand, walk or touch. (About as annoying as the biennale���s website, where brightly coloured words plummet intermittently down your screen.)

William Forsythe���s installation ���Nowhere and Everywhere at the Same Time, no. 2���, though, is a highlight. He���s filled a cavernous room with hundreds of synchronized, swinging plumb bobs on strings, which you���re invited to navigate through (no barriers here). Forsythe, a choreographer known for the experimental dance concepts ��� often using video projections, music, architecture and spoken word ��� that he developed with the Frankfurt Ballet and the Forsythe Company, calls this piece a ���choreographic object���. (The original ���Nowhere and Everywhere at the Same Time���, 2005, featured a solo dancer who moved in a field of pendulums suspended from the ceiling of an abandoned building on the High Line in New York.) Here, you instinctively weave your body in and out of the plumb bobs in time to their hypnotic sway (several got tangled when I wasn���t quick enough; along came an attendant to immediately clean up in my wake).

"Nowhere and Everywhere at the Same Time, no. 2", 2013, by William Forsythe. Photograph: Bob Barrett

"Nowhere and Everywhere at the Same Time, no. 2", 2013, by William Forsythe. Photograph: Bob Barrett

Over in the old prison and school area, there���s a sinister site-specific work by the Japanese artist Chiharu Shiota. In ���Conscious Sleep��� (displayed in the former sleeping quarters), white steel bed frames are held up vertically by densely woven black thread; a powerful glimpse into the dark, nightmarish and claustrophobic minds of the inmates (and schoolgirls), perhaps. Back out into the bright daylight of the prison yard, the electricity cables stretching between the disused buildings look as though they���ve been just as artfully placed.

"Conscious Sleep", 2009/2016, by Chiharu Shiota. Photograph: Ben Symons

"Conscious Sleep", 2009/2016, by Chiharu Shiota. Photograph: Ben Symons

Another wonderful surprise is Miguel ��ngel Rojas���s tessellated floor in the former Mess Hall. Only when up close (there���s a barrier to stop you treading on it) do you realize that the tiles are an illusion, instead made up of finely powdered charcoal, sand and lime. A rock sits in the centre. It���s a delicate challenge to Australia���s history of colonization (this kind of floor pattern is found in nineteenth-century Victorian architecture) and evokes the powerful connection to land felt by Aborigines.

Approaching the Guards House ��� the highest point on the Island ��� a thud-thud, thud-thud shakes the ground, like an eerie heartbeat that grows from a murmur to a bass-heavy boom. This is Cevdet Erek���s ���Room of Rhythms��� (see top image), a series of large speakers scattered in and around the now-roofless building, apparently to do with ��� the blurb tells us ��� the campaigns dating back to the 1850s to reduce the working week from forty-four hours to forty; each pulsation mirrors the workers��� unremitting protests that finally succeeded in 1947. But for me, even without this information, the atmosphere is affecting straight away. A reminder of all those beating hearts, mostly held captive, many of whom probably died on Cockatoo Island over the course of nearly two hundred years. Unlike them, I escaped on a city ferry a few hours later.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers