Peter Stothard's Blog, page 4

July 20, 2016

Non-deliverer, non-deliverer

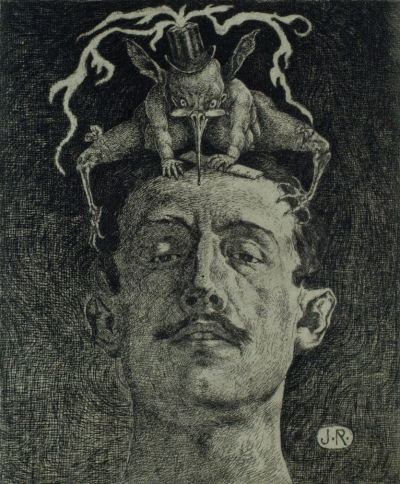

"Criticism" by Julio Ruelas (1870���1907)

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Here at the TLS, reviews are our staple. This is a statement of the obvious, perhaps. No editor likes sending out a book for review and not receiving the review. It���s frustrating ��� and feels like wasted effort. But it happens of course, for a variety of reasons: reviewer���s illness, or other unforeseen circumstances; the book not being worth reviewing; simple forgetfulness. There are other reasons: one reviewer once claimed he had his review impounded by customs officials at Lima airport (this was in the days before computers etc., and he had no copy of it).

A distinguished American historian (who shall remain nameless) has a particular track record of non-delivery. I calculated from our records that this reviewer, over a decade and a half, owes five different editors here in excess of 15,000 words. Now, you may say that it���s our fault as editors for continuing to invite this reviewer to write for us ��� a triumph of hope over expectation. Maybe we should have consulted each other before deciding that this reviewer seemed just right for the book(s) in question.

Personally, I think a reviewer should always deliver, even if it���s several months late ��� or at least explain why they intend not to. After all, in accepting you���ve entered into an unofficial contract. My own first review for the TLS took me several months ��� I was that anxious ��� and, not unreasonably, the book was deemed too old to be reviewed by the time I delivered (my apologies to the author in question, Luciano De Crescenzo). My next review took almost as long. It got a little bit easier, but by small degrees.

After all, reviewing is hard, as most will agree. I shudder when I think back to the sheer torture of my early reviews: the anxiety over the looming deadline, the fear that I hadn���t properly understood the book. I would have a couple of drinks on the evening before the deadline to ease the tension and end up unable to think straight; next step was to set the alarm for early the next morning, but in fact I was unable to sleep at all ��� and I had a hangover to boot. I scrambled through it somehow. But it was no fun. But when the review eventually materializes there is always a sense of satisfaction. That is partly why reviewers do it. And what we rely on.

July 15, 2016

Putting poetry in its place(s)

Creative Commons photo by Shazz

By MICHAEL CAINES

If you should find yourself cooched on your plock, eating your bait under a tree, as the mizzle of a blackthorn winter comes down, your bagging hook beside you ��� well, you've perhaps had the misfortune to have been transported to thirteenth-century England. (Sorry about that.)

It was in this period that St Katherine's Hospital for the poor and aged, the sick and distressed, travellers and pilgrims was founded in Ledbury, by Bishop Hugh Foliot of Hereford. The Bishop's aim was to take care of people's spiritual as well as their material needs; and the poet Adam Horovitz, in his role as Herefordshire's Poet in Residence over the past year, has written a quatrain that sums up this dual purpose neatly:

Keep your crusades. Here is the real

work of God: an end to hunger;

the repair of holes in the hedgerow;

nurture of soil and of soul.

I found that the "Here" of Horovitz's poem caught my eye ��� perhaps because it suggests a contribution to the poetic map of the world. . . .

The term "occasional poetry" puts the emphasis on time while perhaps obscuring the fine, countervailing tradition that puts the emphasis on place. The "in residence" role for poets formalizes the tradition, you might say; and although the poetic "place" in question can be a vaguely platonic as well as a specific, easily enough has been written about, say, identifiable English country houses to fill out a modern anthology.

Shift back to sacred ground: it's with no particular occasion in mind that Philip Larkin's "Church Going" shuffles around the archetypal Anglican House of God, a building empty of people yet full of history and ritual paraphernalia, "not worth stopping for" ��� "Yet stop I did". Here the poet's indifference ("brass and stuff") meets the awful lore of the past ("this accoutred frowsty barn") and the undecided future (those "dubious women" making their children "touch a particular stone"). I'm perhaps not the only reader who's taken a while to read more than one meaning into Larkin's innocent-sounding title, which could be taken to refer to this kind of occasional pottering around, to regular attendance (the church-going of old) and, more tenuously I admit, to the Church itself "going", declining, leaving us to it. . . .

Vicki Raymond describes being likewise brought to an uneasy stop by the Chapel of St Mary Magdalene in Buckinghamshire, pictured above, in her poem "Boveney Church":

Ahead in the mist, a squat church

has suddenly appeared,

like a bully lying in wait

at the edge of the tow-path. . . .

If I should ever forget

myself so far as to marry,

and in church too, it might

well be a church like this one:

so suited to departures

into regions of mist, so flint-faced

in promising so little

and expecting even less.

Larkin's poem asks "When churches fall completely out of use / What we shall turn them into". The Grade I listed Boveney of Raymond's poem hasn't been turned into anything else yet, as many a place of worship has been; instead, it's under the care of the admirable Friends of Friendless Churches. Apparently, concerts and exhibitions take place there, but weddings are "rare exceptions".

Both "Church Going" and "Boveney Church" appear in a new anthology edited by Kevin J. Gardner, called Building Jerusalem: Elegies on parish churches, in which poets such as Fleur Adcock, John Betjeman, Adam Horovitz's mother Frances and Rowan Williams describe specific encounters with specific churches. Despite the urban pilgrimages, such as Betjeman's to St Saviour's in Highbury, the isolation of the church Anne Ridler describes in "Edlesborough" seems emblematic here: "A lighthouse in dry seas of standing corn".

Contrast the mood here ��� misty melancholy ��� with that of Wattle and Daub: Poems celebrating The Master's House, Ledbury, a verse leaflet resulting from Horovitz's residency ��� the Master's House being a Grade II listed building on the St Katherine's site in Ledbury. (It houses, among other things, the John Masefield Archive and the local library, which has apparently seen a marvellous increase in usage of 164 per cent since moving in last year.) It is from Wattle and Daub's glossary I learn that to cooch is to crouch down, a plock is a plot of land or a small field, and a farm worker's bait is lunch; a bagging hook is an "implement for cutting hedges or thistles". Perhaps it would be wise to find a better time of year to trim the hedges of your field than the "very cold spell at the end of winter", especially in a "light rain". If the Master's House is a success story, it was also, as Horovitz notes in "Just a Building in the Car Park", "Brought nearly to ruin / by time and lack of care".

Lastly: there is even more local poetry for local people ��� northerners rather than southerners this time ��� in a recently published volume called Among Woods and Water: An anthology of poetry from Northumberland inspired by the Northern Poetry Library. Poets have been working with the elderly residents of a care home and schoolchildren alike, in places such as Morpeth, Hexham and Alnwick, but also at the Northern Poetry Library itself (which holds "the largest collection of post-World War II poetry in England outside London"). The anthology takes its title, for example, from Lisa Matthews's "Villanelle for the Library":

among woods and water

between words and meaning

a story prepares to be heard

in the telling, voices wait

birds fall below quiet clouds

among woods and water . . . .

For those who like their poetic forms short and sweet, Among Woods and Water also introduces the novelty of an "anchored terset" (sic; the "s" instead of "c" apparently alludes to the word "terse"): three words over three lines, weighed down by the anchor of a full stop on the fourth. Note the acrostic element, too, in this example by Jo Currie:

Napoleon

Posing

Loftily

.

Or this pleasingly pointed one by Pat Hallam:

Neatness

Pleases

Librarians

.

Perhaps, as Matthews admits, this isn't really a form of poetry at all; whatever it is, it got people thinking about the letters "NPL".

And it's an advance, in terms of concision if nothing else, on TLS limericks.

July 14, 2016

Anger is an energy

London���s Outrage fanzine (December 1976) by Jon Savage

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Punk only lasted about two years, roughly from 1976 to 78. The first punk single was the Damned���s ���New Rose��� (which still sounds fresh today), but it all kicked off properly with the Sex Pistols��� ���Anarchy in the UK���. Released in the autumn of 1976, it was banned from most radio stations (I have a dim recollection of first hearing it, crackling and bobbing on the waves on the pirate station Radio Caroline ��� ���I thought it was the UK / Or just / Another / Country���).

In the foyer of the British Library is a mini exhibition which may have bemused some of the BL���s regular patrons. Marking forty years since the birth of punk, it displays the sleeves of all the significant punk singles, with bands ranging from the Clash to the Rezillos (���Can���t Stand my Baby��� with the singer Fay Fife���s lovely Edinburgh lilt). They���re all available to listen to ��� and people were doing plenty of that when I visited. Also on display are fanzine covers, outraged tabloid front pages from the time. I was reminded of the fact that the Sex Pistols were nominated Young Businessmen of the Year in 1977 ��� presumably after they���d been expensively fired by the record company EMI (this was not long after they had signed their contract very publicly outside Buckingham Palace). And if you want to revisit the infamous Bill Grundy TV interview with the Pistols, it���s there (and on YouTube).

Was it a movement for social change? Who knows. The country was certainly in the doldrums at the time, and a dull place to live. The Clash, for one, had a political message, and drew attention to racial tensions in songs such as ���White Man in Hammersmith Palais���. But I sense it was also about having fun: the Damned���s drummer was called Rat Scabies; the Adverts, meanwhile, would boast that they couldn���t play a note (���One Chord Wonders���); the unfortunate Sid Vicious, who replaced the musically talented Glen Matlock in the Sex Pistols, really couldn���t play.

Johnny Rotten, 1976 ��� Photo by Ray Stevenson/Rex Features

The lead singer of the Pistols, Johnny Rotten (above, and subsequently of Public Image Ltd or PiL, as John Lydon), was recently interviewed at the BL by BBC Radio 6 Music���s Stuart Maconie. Lydon remains combative, verbally taking on a member of the audience. And to the question ���what���s punk for you?���, Lydon replied ���It���s something you wouldn���t have without me���. He also managed to sound rather like the old codger he has perhaps become (although he is only sixty) ��� ���young people these days ��� they���re so internetty���.

There was a decent turnout (possibly of ageing punks). Lydon published a lively and somewhat prolix autobiography in 2014, entitled Anger is an Energy (a line from PiL���s anti-apartheid song ���Rise���). We read about his childhood afflicted by meningitis (it ���came from the rats���) and his tough upbringing in Finsbury Park. He���s rather better read than I���d imagined (he read Crime and Punishment at the age of eleven) and more tolerant of other forms of music (including disco!) than was apparent at the time. Now he ���love[s] Mozart, beyond belief���. There is a good deal of score-settling, in particular with the late manager of the Sex Pistols and self-publicist Malcolm McLaren, and several swipes at McLaren���s one-time partner, the designer Vivienne Westwood (���She never ever understood the human shape���); but he displays loyalty to his band members: ���Steve [Jones] and Paul [Cook] and Glen [Matlock] did amazing things for me. I will love them till the day I die���. And in case anyone should think the Pistols were just an obnoxious bunch of anarchic hoodlums, he points out that they played two gigs for striking miners in Huddersfield on Christmas Day in 1976.

Their final gig was in San Francisco in January 1978, at the end of a disastrous tour of the US (McLaren, in his infinite wisdom, had chosen to book most of the dates in the Deep South, with predictable consequences). Rotten���s final words to the San Francisco audience were: ���Ever get the feeling you���ve been cheated?��� It's a question I'd like to put to the millions who fell for Boris Johnson���s Brexit campaigning lies recently. Far from being cast into the political wilderness for his duplicitousness with the voters, Johnson has just landed the job of foreign secretary. Oh dear.

July 12, 2016

The journalist in fiction and film

Michael Caine in The Quiet American

By LAURA FREEMAN

Jasper Milvain, hero without scruple of George Gissing���s New Grub Street, is a hack���s hack. "It is my business", he smugs to his sister, "to know something about every subject ��� or to know where to get the knowledge." This passing acquaintance with any and all subjects is then profitably flogged round Fleet Street.

He writes a book review ��� three quarters of a column for the Evening Budget ��� after breakfast and a Saturday "causerie" for the Will-o���the-Wisp before lunch. Then a sketch ��� to be finished tomorrow ��� for The West End. Between tea and dinner, he reads four newspapers and two magazines, and he finishes an essay for The Current before bed. By such industry does a man make a living by his pen.

It's no good being high-brow, Jasper tells the dogged, Tibullus-reading Edwin Reardon, who aspires to literary criticism: "I will only mention, as a matter of fact, that such work is indifferently paid and in very small demand".

While Jasper churns out his thrice-daily trifles, Edwin starves and turns threadbare among his drafts and blotting paper and wastepaper baskets. Jasper thrives, Edwin moulders and, though Jasper is a disreputable rotter and Edwin honourable, it is Jasper one roots for and wills to succeed.

We like our fictional journalists in the Jasper mould: flip and arrogant, unscholarly and know-all, vain and neurotic, and willing to push their grandmother off the end of the pier ��� "GRAN IN SEA SHOCK SAVE" ��� if it means a cover story. The more incompetent (William Boot in Scoop), cynical (Thomas Fowler in The Quiet American) and dishonest (Rita Skeeter, the tabloid gorgon of Harry Potter���s Daily Prophet) they are, the more we like them.

Sarah Lonsdale, in a symposium at City University entitled The Journalist in British Fiction and Film on Thursday evening, put it to the room that while we may respect the "foot-slogging reporter", the noble war correspondent, "the high-minded, truth-seeking" missionary, we are "fascinated" by the journalist who is ignorant, irresponsible, indolent, a "nervous wreck", but who always gets his story.

Does it matter whether the story is true? Not necessarily. A good story trumps an accurate one. She cites Rudyard Kipling���s short story The Village That Voted the World Was Flat, in which an invented news story is taken up across "two hemispheres and four continents". One of the inventors of the story admits: "We couldn���t stop it if we wanted to now. It���s got to burn itself out. I���m not in charge any more".

One panellist, Eric Clark, an investigative journalist and the author of several spy novels, puts it more bluntly: "All journalists are liars". This, he says, makes them ideal spooks. Anthony Blunt and Guy Burgess both wrote for the Spectator, and the British intelligence services used to recruit from the Economist, the Observer, the Sunday Times and the BBC���s ranks of "Our man in . . .". The CIA, according to Clark, has walls of spy novels in its library, to be plundered by staff for espionage inspiration.

If we journalists are not betraying our country, we are fiddling our expenses. Philip Norman, biographer of the Beatles, John Lennon and Paul McCartney and a staff writer on the Sunday Times Magazine in its Sixties heyday, remembers an annual competition "Expenses Man of the Year". The journalist James Fox won it once, with an expenses form that simply said: "Taxi there . . . and back".

This was the age of the bottomless expense account. Norman took himself off to America to interview Stevie Wonder, Diana Ross and P. G. Wodehouse, and, having done so, sent a message back to Godfrey Smith, the Editor of the Magazine, saying he "needed some time to think about all these stories ��� so can I come back on the QE2?"

"Of course, dear boy."

"And could I come back first class?"

"Of course, dear boy, of course."

The Magazine���s scoops and expenses claims were paid for by luxury advertising: butter, white carpets, After Eight chocolate mints. "The Mag soaked up advertising money", says Norman. This led to such incongruous page layouts as a photo-journalism story about children burned by napalm in Vietnam opposite an advert purring: "Double cream ��� spread it thick".

Godfrey Smith, we were told, was resistant to editorial interference. When memos came from the Sunday Times Editor Harold Evans requesting that a story be covered, Smith would dictate: "Compose vibrantly grateful response of which underlying message is: 'Piss off'". Smith once took the whole office on a jolly to Yugoslavia ��� not a word of copy ever appeared.

Ian Richardson, who spent fifty years at the BBC, said that he never fired a reporter for dishonesty or because he was suspected of being a spy, but only if he failed to deliver a story. Richardson has written a novel, The Mortal Maze, with an "ethical" journalist at its heart. The extracts did leave one thinking that an unethical one might have been more fun.

You have to admire the journalist Humphrey Quain in Alphonse Courlander���s novel Mightier than the Sword (1912), quoted by Lonsdale, who is sent to cover a French winegrowers��� riot and is crushed in the scrum. As he lies dying, "an odd, whimsical idea twisted his lips into a smile as he thought: 'What a ripping story this will make for The Day'".

The Journalist in British Fiction and Film: Guarding the guardians from 1900 to the present by Sarah Lonsdale will be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS.

July 10, 2016

Thanks for that!

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

A TLS subscriber writes to us (by snail mail) from Ann Arbor, MI: ���Dear TLS: Because the recent vote to leave the EU seems to me to raise serious doubts about Great Britain���s Collective Intelligence, and because for many years I have considered the TLS an embodiment of that Collective Intelligence, it is time for me to cancel my subscription���.

This is surely an unforeseen consequence of the Brexit result. Voters should have thought of the implications for the TLS���s subscriber base before choosing to vote Leave.

The letter writer goes on: ���I am quite aware that we in America are in some danger of committing a comparable Collective Stupidity. You, and I, must share the blame if we don���t speak out wherever possible. Good Luck, . .���.

Should the unthinkable happen in the US in November, I urge all British subscribers to the New York Review of Books ��� in a spirit of solidarity ��� to cancel their subscriptions forthwith!

July 8, 2016

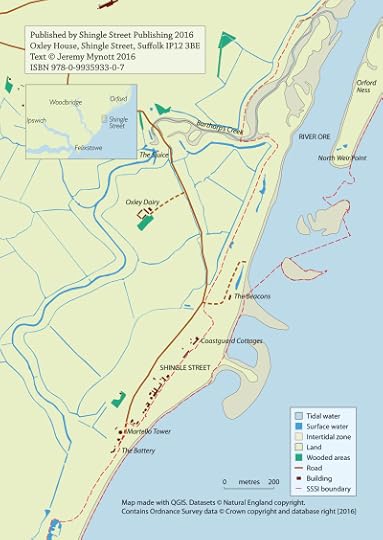

(Wild)life in Shingle Street

Narrow-mouthed whorl snail (Vertigo angustior); credit: Toby Abrehart

By JEREMY MYNOTT

Shingle Street is a tiny hamlet in Suffolk perched precariously, as the name suggests, between land and sea. There are just twenty-nine dwellings and a shifting population of some sixty adults and children ��� but that���s only the population of Homo sapiens. We are surrounded here by a much greater number of other life forms, which also give this place its identity. That Shingle Street is classified as a "Site of Special Scientific Interest" and is part of an "Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty" has nothing to do with the beauty or interest of its human residents, alas. It���s all down to the wildlife, and in 2015 we ��� that is, the residents of Shingle Street ��� decided to survey and record this larger local community.

The idea for the survey arose when we were thinking about the best ways of protecting Shingle Street from the various risks it faces ��� from the sea, from outside interests . . . and from ourselves. There were lively community discussions that understandably centred on the need to safeguard livelihoods and property, but I argued that they weren���t worth a row of beans if we were trying to attract outside support. It was the environment that really mattered. That is what makes this stretch of Suffolk coastline such a significant part of our local and national heritage.

You make a suggestion like that at your peril, of course, and I was duly charged with organizing a full ecological survey and then writing up a readable account of it. And quite apart from any practical or political benefit there may be in having such a register of the natural wealth of the area, it has been worth doing. Britain���s wildlife is currently threatened as never before. In the past fifty years we have lost more than half of it, mostly through our own agency. That is a staggering statistic, and should be a deeply shocking one. Here, for example, are the headline figures for the decline of some much-loved species of British breeding birds, all deeply embedded in our national culture: skylarks down nationally by 61 per cent, cuckoos and curlews by 62 per cent, nightingale by 90 per cent and turtle dove by 96 per cent (so now almost extinct); and the figures for flowers, butterflies, moths and other insects are as bad or worse.

Curlew; credit: Margaret Holland

Local inventories of the sort we attempted are a first step in advertising this crisis and raising public consciousness about its significance. "Let us not underrate the value of a fact", said the great American naturalist Henry David Thoreau, commenting on a grander survey in his own day ("The Natural History of Massachusetts", 1842); "it will one day flower in a truth". I hoped the Shingle Street initiative would be a tiny contribution towards such larger purposes.

The community responded splendidly. We formed ourselves into various survey teams, who were trained to record the easier groups such as butterflies, mammals and reptiles, and I recruited experts to do the more difficult ones such as aquatic invertebrates, bush crickets and the specialized flora. I also pulled in all the existing databases of historical records from visiting naturalists and added my own (mainly of birds). The full technical report can be studied on our website, which has an archive of images of the more striking species recorded, and contains a link to my more popular booklet too.

So, what did we discover? Some remarkable things. No one guessed we might have had more than 300 different moths visiting Shingle Street, or fifty-nine species of spiders. We found otters, bee orchids, harvest mice and clouded yellows, as well as less charismatic sea slugs, sedges and molluscs, including a tiny snail, Vertigo angustior (see picture, top), which is a national rarity but was present here in estimated numbers of more than 4 million on July 23, 2015!

Here are the overall statistics:

Moths 379

Flowering plants 314

Birds 222

Spiders 59

Molluscs 58

Beetles 48

Mosses 36

True bugs 32

Lichens 28

Butterflies 26

Mammals, terrestrial 23

Dragonflies and damselflies 15

Crustaceans 15

Bees, ants, wasps 15

Grasshoppers and crickets 9

Mammals, marine 4

Reptiles 4

True flies 4

Leeches 3

Algae 2

Amphibians 2

Harvestmen 2

Others 5

Grand total: 1,305 (plus one hominid)

Hummingbird hawk moth; credit: Toby Abrehart

This roll call is impressive for such a small hamlet, but it is still very incomplete, with many gaps that for reasons of time or expertise we could not give proper attention. Terrestrial beetles, bats, bugs, bees, algae and fungi in particular all need further study. The true total could easily be well over 2,000.

Numbers alone are just indicators, however. All these species have their interest and importance but, to paraphrase George Orwell, not all species are equal. Scientists now believe that we may be facing another "great extinction" in the long history of the planet, and one caused for the first time not by external factors but by the behaviour of just one dominant species, the puny but inventive Homo sapiens. Surveys like the present one represent small cries of protest and hope, and the title of my booklet, Knowing your Place, suggests the need for both knowledge and humility in the endeavour.

July 6, 2016

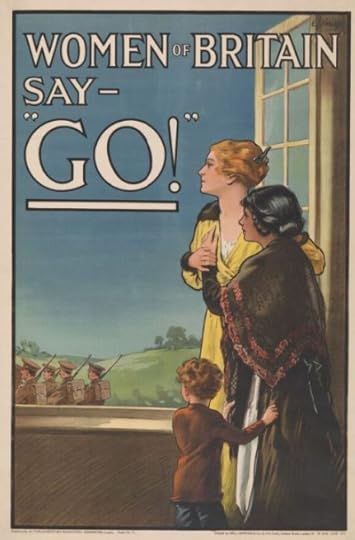

Women and the Somme

A poster by E. V. Kealey, 1915, for the British army recruitment campaign

By ALEX BURGHART

This week I have been thinking about my great grandmother, Sybil Maidment, who was born in 1895 and grew up in Somerset. For the last few years of her life, until she died in 1987, she lived with my parents and me. I adored her. If asked why I���m interested in history, I say it���s because I knew her and because she had known her grandmother, Grandma Prince, born in 1815, whose parents had known life before the French Revolution.

As the country dredges up the horror and pathos of the Somme a hundred years on, I have been remembering how, more than thirty years ago, I first came to hear of the First World War. I was seven, or thereabouts, and going about my first paid job ��� taking my great grandmother (or Nanny, as I called her) her morning tea. I was paid 10p a week for the task ��� a great sum of money for a seven-year-old in 1985 ��� on condition that I did not tell my parents that I was adding whisky to the mix (years later, I discovered that they knew). This, itself, was an act of familial historical significance ��� as a girl, Nanny had been employed to lace Grandma Prince���s tea with gin.

Nanny would take tiny sips from her huge cup and saucer as we talked with the curtains still drawn. Most of the time she���d tell me stories. One morning I asked her why her friend, Miss H., had never married. And she told me about a terrible war in which all the young men had gone away and had not come back. It made me cry. It makes me cry now.

My great grandfather, Harry (or Gramp), who died shortly before I was born, had been exempt from military service on account of a heart murmur. This marked an odd quirk in evolutionary history whereby biological weakness made it more likely that your DNA might be passed on. So it was that Sybil and Harry had each other and a daughter and Miss H. had no one, or at least no one of her own. She worked for the local butcher and when he died, much to the shock of the town, he left her ��� and not his wife ��� the shop. We never knew whether this was love ��� but if it was, it was symptomatic of an age in which there were not enough men to go round.

The Somme and its war are largely masculine in their imagery. Men in uniform, men in mud, men in death. Young men in black and white caught in the teeth of an industrial atrocity. The 744,000 British men whose names are writ in stone were all sons, and many were brothers to sisters and husbands to wives. But a great multitude were not married and the women they never married, never married either. A generation of maiden aunts were widowed before they were wed.

In 1917, a senior mistress is supposed to have said to a sixth form girls' school: "I have come to tell you a terrible truth. Only one out of ten of you girls can ever hope to marry. This is a statistical fact. Nearly all the men you might have married have been killed. You will have to make your way in the world as best you can". By the census of 1921, after Spanish influenza had torn through post-war Europe, there were 1.9 million more women than there were men in Britain. Press and politicians came to call them, somewhat coldly, the Surplus Women.

These women did indeed make their way as best they could and, in so doing, set in motion a world in which their sex was less defined by marriage. But if, as D. H. Lawrence wrote, mutual love is "like a magnet���s keeper / closing the round", then, for very many, the decades that followed were incomplete. Their sacrifice deserves no less remembrance.

July 4, 2016

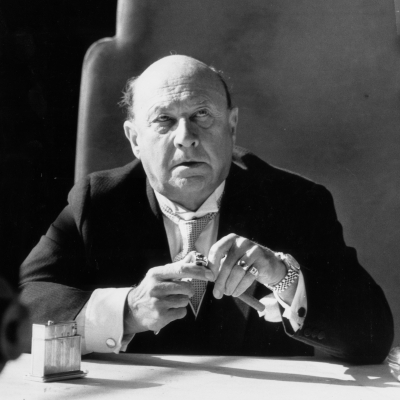

Waugh on screen

Donald Pleasence as Lord Copper in Scoop (1987)

By ALEXANDER LARMAN

The news that Evelyn Waugh���s first and, to many, most beloved novel Decline and Fall is to be adapted by the BBC, fifty years after his death, was met with a mixed response. On the credit side, the writer is the estimable James Wood, whose sitcom Rev exhibited a knack for wit and absurdity that stands him in good stead. A supporting cast that includes David Suchet and Douglas Hodge breeds similar reassurance. But the adaptation stars Jack Whitehall as Waugh���s hapless Paul Pennyfeather, and one fears that Whitehall may merely serve up a period reprise of his similarly useless pedagogue Alfie Wickers from his own show Bad Education (which he wrote with Freddy Syborn).

Whether the result lives up to expectations or not, it is heartening to see one of Waugh���s comic novels being adapted for television, especially one that has been attempted only once before, in the Sixties, and then extremely badly. (A shame: one wishes for Michael Hordern as Prendergast, James Robertson Justice as Dr Fagan and Terry-Thomas as Grimes.) Although Waugh seems to have been adapted a fair amount over the years, his reputation in terms of television lies almost entirely on the seminal (if, it can now be said, overlong) ITV version of Brideshead Revisited (1981), with little else having captured the subversive joy of his peerless prose.

Jeremy Irons as Charles Ryder and Anthony Andrews as Sebastian Flyte in Brideshead Revisited (Episode 1), 1981

The writer who is perhaps most closely associated with Waugh today, outside his family, is William Boyd. Having being compared with him early in his career ("you can just as easily be described as a ���poor man���s Kingsley Amis���", he told me recently when I asked him about his experiences of adapting Waugh; "in fact I think we���re very dissimilar writers"), he went on to adapt Scoop in 1987, and in 2001 turned the Sword of Honour trilogy into a three-hour, two-part film, starring a pre-Bond Daniel Craig as Guy Crouchback. Boyd confesses to "a mild obsession" with Waugh, and has written about him extensively: "we both have a very dark sense of humour", he told me, "and Waugh's sense of humour has always been, in my opinion, his greatest asset. As soon as he starts getting serious (and less humorous), the work suffers".

Boyd���s first foray into Waugh-land with Scoop was panned, and he says now that "we did get a pasting but, in my opinion, that was because the film was ludicrously over-trumpeted and we were heading for a fall, come what may. We ended up with 14 million viewers and I still stand robustly by the adaptation. I think it's very good ��� with a brilliant cast ��� and very funny". One imagines that if Decline and Fall were to obtain half that number of viewers the producers would be thrilled ��� and not a little surprised, despite the mass appeal of Whitehall and his glamorous co-star Eva Longoria as Margot Beste-Chetwynde, a far from desperate housewife.

The problem with adapting Waugh is that his humour is predominantly verbal rather than visual, and this can lead to a film either spelling out the jokes too literally or missing them altogether. Boyd argues that "it's an abiding problem in adaptations because of the vast difference between the two art forms (novel and film). The latter is photography and thereby lie all the difficulties. It's very hard, if you're looking through a camera lens, to be subjective. Film ��� and this is not meant to be derogatory ��� is a very simple way of telling a story. A novel is infinitely complex, by comparison. When you come to adapt something as subtle and nuanced as a Waugh novel you are up against it. The only solution is to play to the new medium's few strengths. When I adapted Sword of Honour, Ritchie-Hook's insane assault on the German blockhouse is brilliant ��� it's suddenly a war movie".

Boyd argues that one reason Waugh hasn���t been adapted more often is that the biographical aspects get in the way: "he's too well known, and everybody has an opinion (snob, fascist, comic genius, Catholic stalwart etc). So the criticism is ephemeral and people can make up their own minds once the brouhaha of a release has died down. He's no harder to adapt than any novelist of serious talent. You just have to judge the adaptations as films ��� and not as versions of the novels. If you enjoyed the films then the adaptation has succeeded".

Matthew Goode as Charles Ryder, Hayley Atwell as Julia Flyte and Ben Whishaw as Sebastian Flyte in Brideshead Revisited, 2008

Certainly, the appearance in 2008 of a film of Brideshead Revisited (with a screenplay by Jeremy Brock and Andrew Davies) excited few, owing to some unfortunate miscasting; fine actor though he is, Ben Whishaw is simply not convincing as Sebastian Flyte, any more than Emma Thompson is a persuasive Lady Marchmain. Boyd believes that it could be adapted again, and more successfully ��� "I think it would be far more interesting to look at the undercurrents of the novel rather than its 'English Heritage' virtues". He���s happier with what he did with Sword of Honour, although it had to be condensed from its planned six-hour length ��� "the main themes of the novel are treated really well, I believe, and in some senses more credibly than the books (Guy's marriage, for example). It also has a scale and scope that I marvel at, today".

Although he hasn���t been consulted about the new Decline and Fall, Boyd cites it as one of the two books by Waugh (the other is The Ordeal Of Gilbert Pinfold) that he would have liked to adapt. And if he were to offer Wood, Whitehall & co some advice? "Don't think of the novel, paradoxically. Think of the type of film you want to make ��� and then play to the medium's strengths". We shall see what the end result is, but one hopes for a black comic feast worthy of its creator ��� and, if it���s successful, long overdue versions of Pinfold, Black Mischief and the rest. Waugh himself was a great cineaste ��� Vile Bodies has several scenes that were influenced by the cross-cutting and montage of late 1920s cinema, and he even appeared in a student film, The Scarlet Woman, when he was at Oxford, playing the Dean of Balliol in a ridiculous fright wig. Perhaps it���s time for a bold writer to depict the great man himself in a biopic. Chances are, it would be impolite, shocking and very funny indeed.

July 2, 2016

Safe in the Anglosphere

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

We have yet to take the proper pulse of writers��� reactions to the referendum result. There were the instant tweets: Salman Rushdie���s ���Old Farts 1 The Future 0. Well done England [sic]. Maybe lose to Iceland next & get out of Europe properly���. Prescient there. J. K. Rowling���s ���I don���t think I���ve ever wanted magic more��� should become immortal. Meanwhile Irvine Welsh���s response was characteristic: ���Selfish old cunts fucking things up for youth? Well there's a first!���

And then there were some reactions on the 3:AM online magazine: ���Brexit is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake���, from Ali Smith, for example. There was Will Self with some trenchant and hard-to-disagree-with opinions.

At the same time the thought occurs to me: maybe we were never truly culturally connected to the Continent. I just stumbled across an item entitled (again, presciently) ���Brexit of the Mind��� from February 2016 by the Sunday Times journalist Bryan Appleyard in which he writes of how he asked various British (male) writers for their ���choice of current European fiction���. Kazuo Ishiguro���s ���mind went blank��� and he instead mentioned a few films such as Les Parapluies de Cherbourg. That film appeared in 1964!

Martin Amis agrees with Appleyard that the English language ���has made us cultural Brexiters���. Amis reveals that he doesn���t read European literature. Only as a ���last resort��� he reads ���unignorable writers��� such as Kafka and Tolstoy. ���There are very, very few European writers who have made an impression outside their own country. [Debatable.] G��nter Grass with The Tin Drum . . . . Michel Houellebecq is the only one who���s got any kind of reputation in the whole of Europe.��� What about Elena Ferrante? Or Knausgaard? He goes on to say that ���there���s no earthly reason why anyone in the Anglosphere should desperately want to learn a foreign language, but there���s every reason why a German or Dutch or French person should���. So that���s all right then.

Amis then makes the curious observation that English is not only the most dominant language; it is ���also the most literary���. This strikes me as absurd. How does he know? Surely a language is as literary as a writer deploying it makes it? He tells Appleyard that on a recent trip to Europe, ���all the writers [he] met were ���singing the praises��� of the English language���. Nice for him, but it���s clear that there would have been little reciprocal sentiment.

This may explain Amis���s approximate grasp of foreign terms when he uses them in his fiction: in The Pregnant Widow (2010), we read ���They were the children of the Golden Age (1948?���73), elsewhere known as Il Miracolo Economico, La [should be Les] Trente Glorieuses, Der [should be Das] Wirtschaftswunder���. The collection of short stories Heavy Water (1998), meanwhile, which includes that great story ���Career Move��� about a minor English poet and a Hollywood screenwriter trading places, contains several ���foreign��� errors: the poet Paul ���C��lan���, ���ruse du [de] guerre���, ���desaparacidas��� for the Argentinian ���desaparecidas���. In an eviscerating review in the LRB of Amis���s most recent novel The Zone of Interest, Michael Hofmann wrote ���A curious feature of this macaronic German ��� nicht? ��� is that it has a zero tolerance policy for umlauts. I don���t think I saw a single one���.

Did no editor at Cape spot any of these errors over the years? Or ��� unworthy thought maybe ��� did they feel unable to tamper with their pre-eminent novelist���s manuscript? I imagine it���s the only thing the editor would have needed to do. Why allow foreign languages to be treated with such apparent casualness? Now, more than ever, we should be more vigilant in that direction. Even if it���s only about perceptions.

July 1, 2016

Michael the Third?

By DAVID HORSPOOL

He wasn't angling for it ��� honest: "I never thought I'd be in this position. I did not want it, indeed I did almost everything not to be a candidate for the leadership . . . ". To put it another way, "Your love deserves my thanks; but my desert / Unmeritable shuns your high request". In any case, he really isn't cut out for it: "Whatever charisma is I don't have it, whatever glamour may be I don't think anyone could ever associate me with it". Yes, "so much is my poverty of spirit, / So mighty and so many my defects, / As I had rather hide me from my greatness".

Of course it needn't have come to this: "I knew we needed a leader who both believed in this new path and who could build and lead a united team to guide us through the challenges ahead. I believed that Boris Johnson ��� who had campaigned alongside me with such energy and enthusiasm ��� could build and lead that team". That's right, "God be thank'd, there's no need of me, / . . . the royal tree hath left us royal fruit, / Which, mellow'd by the stealing hours of time, ���/ Will well become the seat of majesty, / ���And make, no doubt, us happy by his reign". ���

But what's this? "I came to realise that, for all Boris's formidable talents, he was not the right person for the task". We are not told why. Something to do with "the corruption of abusing times", no doubt. And "That realisation meant that I once more faced a difficult decision". Exactly: "Alas, why would you heap these cares on me? / I am unfit for state and majesty;��� / I do beseech you, take it not amiss;��� / I cannot nor I will not yield to you���". ���

���But "Could I recommend to friends, colleagues and the country a course in which I no longer believed? I could not. I had to stand up for my convictions. I had to stand up for a different course for this country���". Indeed, "Since you will buckle fortune on my back, / To bear her burthen, whether I will or no, / I must have patience to endure the load���". ���

������What can possibly go wrong?

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers