Peter Stothard's Blog, page 7

June 1, 2016

His nibs: Visiting the Stephens Collection

By DAVID COLLARD

The final poem in Julian Stannard's latest collection, What were you thinking?, is entitled "East Finchley". Here it is in full:

It's always sunny in East Finchley.

It's always funny in East Finchley.

That's enough about East Finchley.

East Finchley has a few things to snag the fl��neur's interest: the Phoenix cinema, with its baroque auditorium and jazz moderne exterior; the Bauhaus-influenced Northern Line tube station with its modernist archer statue aiming an arrow straight at the heart of London; Black Gull Books, one of the very best second-hand bookshops in the capital and . . . well, that's about it. The place lacks romantic allure.

Although John Betjeman never eulogized the district as he did nearby Holloway and Highgate, in 1971 he agreed to become the first Patron of the Finchley Society, sending an equivocal message of support: "Long live Finchley and its sudden steep hills, tree-shaded gardens and memories of a civilised prosperity".

Finchley proper is a mile to the north-east and home to the Stephens Collection, displayed in a grand Victorian pile called Avenue House on East End Road. This is the former home of Dr Henry Stephens, FRCS (1796���1864), inventor of the celebrated blue-black writing fluid known as Stephens' Ink.

Stephens' ink was patented in 1837 and became a huge commercial success ��� free-flowing in all temperatures, indelible and unfading, it also had a low acid content, so it didn't corrode steel nibs. Inky Stephens, as he was popularly known, made a huge fortune and became the Tory member of parliament for Hornsey and Finchley, later Margaret Thatcher's constituency, He was a generous philanthropist, dubbed "the uncrowned king of Finchley".

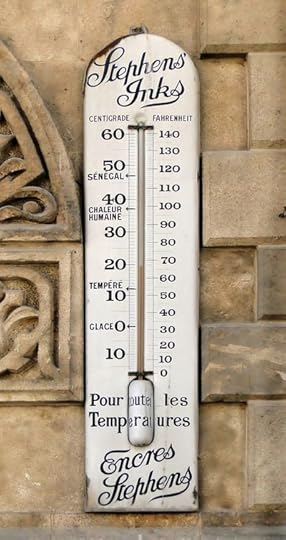

His company branched out into manufacturing fountain pens and other office supplies. Stephens' was for more than a century a household name, the firm's distinctive enamel advertising thermometer adorning public buildings from Istanbul to Dunedin. The Stephens Collection has a fine display of the company's beautifully packaged products for schools and offices: stamp pads and endorsing ink, gum mucilage, typewriter ribbons and carbon paper, wooden rulers, blackboard chalk, crayons and sealing wax ��� a lost world of stationery. Children can learn to handle an ink pen and even a quill, while for grown-ups of a certain age there are potent memories of inkwells, bungies and blotch. Does any TLS reader recall playing dab cricket?

The Stephens Collection was established by the Finchley Society with the assistance of the Writing Equipment Society and the support of the London Borough of Barnet. I spent a perfectly contented afternoon there ��� and you may want to do the same, perhaps exploring the other delights of this unglamorous north London arrondissement. You'll find one of them in the grounds of Avenue House: a statue of a local resident and Finchley Society supporter ��� Spike Milligan.

Stephens' Inks exterior thermometer, 1920, Hotel Baron, Aleppo, Syria; Credit: Bernard Gagnon

May 31, 2016

���There is just one thing ��� the truth���: an interview with Roberto Saviano and David Hare

Roberto Saviano; credit: George Torode

By CATHARINE MORRIS

Ten years ago, at the age of twenty-six, the Italian writer Roberto Saviano published Gomorrah, an anatomy of the Neapolitan mafia. It was inspired by his own disturbing experiences of violence in his home city, and grew out of an extended period of undercover investigation.

In an article published in the Financial Times last year, Misha Glenny described what life has been like for Saviano since then:

���He is shadowed wherever he goes by between five and seven armed members of the Carabinieri, the elite police squadron that has been responsible for his security since 2006 . . . . To begin with, he had to sleep in a different apartment every night; his family have either been forced into witness protection or compelled to renounce him; and even abroad he needs armed protection around the clock. To this day, he cannot possibly form normal relationships as anyone close to him is transformed automatically into a proxy target for the Camorra. Unlike Salman Rushdie���s fatwa, which was negotiated away by the Iranian and British governments, the Camorra death sentence is for life.���

It was slightly surprising to me that Saviano was in a position to give his own account of things at an event hosted by English PEN in London on Thursday. Chaired by Gaby Wood and also featuring David Hare, the discussion was held in a conference room at the Emmanuel Centre in Westminster and attended by a couple of hundred people (perhaps), a fair number of them Italian. Saviano spoke (and listened) through the supremely skilful interpreter Martin Esposito; and confessed early on to certain naivity in writing Gomorrah ��� ���I didn���t decide to walk bravely into the flames . . . . I was young��� ��� while also pinpointing why the book had the effect it did. ���What scared the power I wrote about was not so much [the book as] the readers, the army of readers . . . . Even those who disagreed about the book had spoken about it."

David Hare, Roberto Saviano and Martin Esposito; credit: George Torode

Saviano and Hare were in 2011 jointly awarded the PEN Pinter Prize, which rewards writers who display, in Pinter���s own phrase, ���unflinching, unswerving, fierce intellectual determination . . . to define the real truth of our lives and our societies���. One of Wood���s lines of questioning (one also pursued at a recent London Library event, incidentally) was about whether a writer should be motivated in their work by a sense of social responsibility. Hare was with Cyril Connolly on this ��� ���If C��zanne wants to paint apples, then he���s free to paint apples��� ��� but he also observed that, in his own case, his ���temperament has coincided with curiosity about the world artistically���. (As Wood reminded us, Hare���s plays have examined the judicial system, the banking system and MI5.)

Saviano was still a child when he was overcome by the desire to write. His style was baroque ��� ���as far away as possible from reality��� ��� but when a priest was murdered by the Camorra, he found that he ���could not not look for moral reasons���. He described to us his thought process at the time: ���I���ve got to put my words into the factory, I���ve got to hone them, I���ve got to work with them. I���ve got to get them working in order to make a difference���. But the feeling of responsibility can also be debilitating, he suggested ��� it can be very similar to guilt, and has in the past ���engendered behaviours that would not really belong to me except that I���m fearful of harming others���. He was reminded of the television version of Gomorrah, for which Saviano removed ���everything that���s good in any character���, his reasoning being ���I want evil to be inescapable for [the audience]. I want them to say, ���I���m not like this, and if I���m not like this, why?������ The reaction to the series was unexpected, it seems: ���the world is telling me that in this way I���m inspiring evil, I���m making it fascinating���. There is no duty, he concluded. ���There is just one thing ��� the truth ��� and this is what we need to pursue.���

Saviano���s book ZeroZeroZero, published last year, describes London as the money-laundering capital of the world. When Saviano is in the UK or the US, he told us, he senses that people think him unduly obsessed with ideas about corruption. ���I understand that point of view . . . . It���s so hard to imagine London . . . as such a corrupt entity. By corruption I don���t mean . . . the police, the politicians, the bureaucracy; I mean financial corruption���. He referred to a rank order in which Switzerland is in position one in terms of corruption and lack of transparency, and the UK is at fifteen. That might not seem too bad, he said, ���except that there���s an asterisk��� ��� ���it only applies to the island of Great Britain, not to any offshore British territories which would immediately project Great Britain to the top���. Saviano also said that, were the UK to leave the European Union, it would be ���devoured by foreign capital���.

Hare, meanwhile, spoke of the EU referendum as something that ���in theory is meant to be about the country at large, but . . . is about a power struggle among the Conservative Party���; and told us that when he wrote about the financial crisis, he had ���never met a group of people so totally self-interested as the bankers���: ���they knew nothing about anything except themselves���. Our sense of being ���excluded from everything that is significant��� makes us feel helpless, he said ��� and one of the things he finds interesting when writing about his own times is the strength of audience response to ���oppositional��� material. His new short play Ayn Rand Takes a Stand is currently playing in the West End (as part of A View From Islington North directed by Max Stafford-Clark); and the reaction to it, he said, is ���disproportionate to its quality���.

Saviano said that we���ve all got homework to do: "to get to know things���, to debate. He suggested that we follow the activities of Transparency, and read documents published by the Secret Intelligence Services. As Hare pointed out, we can also do something much simpler. ���You come to look in your own life . . . and the lives of those near you for individual acts of goodness as being the way in which it is possible for you to express yourself���. Saviano had said something along these lines himself: ���I believe in goodness, the good gesture ��� eye to eye, hand to hand; and I hope my readers will believe in this too���.

May 29, 2016

���Oh, if I could write like that!���

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

In a letter to the TLS in 2012, Charles Elliott neatly precised Virginia Woolf���s experience of reading Proust, as related in her letters and diaries. He pointed out that on January 21, 1922, she wrote: ���Everyone is reading Proust . . . . I am trembling on the brink���. By August 18 she revealed, ���Next I go on to Proust���. By April 18, 1923, ���I am reading Proust��� and, two years later (April 8, 1925), it���s ���Proust, in whom I am embedded���. By July 20 of that year a note of exasperation has crept in: ���Proust I should like to finish���. Three years on again, things haven���t improved markedly, if this entry (dated June 20, 1928) is to be believed: ���Take up Proust after dinner & put him down���. Oh dear. Sounds as though she is forcing herself by now. And what are we to make of this revelation, six years further on (July 22, 1934)? ���I followed my new diversion of book binding. I am covering Proust in little shiny squares of gummed paper���.

Yet in 1922 she also wrote to Roger Fry: ���My great adventure is really Proust. Well ��� what remains to be written after that? I���m only in the first volume, and there are, I suppose, faults to be found, but I am in a state of amazement; as if a miracle were being done before my eyes. How, at last, has someone solidified what has always escaped ��� and made it too into this beautiful and perfectly enduring substance? One has to put the book down and gasp. The pleasure becomes physical ��� like sun and wine and grapes and perfect serenity and intense vitality combined. Far otherwise is it with Ulysses; to which I bind myself like a martyr to a stake, and have thank God, now finished ��� My martyrdom is over. I hope to sell it for ��4.10���.

(How strangely precise that ��4.10 is.)

Again to Fry, ���Proust so titillates my own desire for expression that I can hardly set out the sentence. Oh, if I could write like that! I cry. And at the moment such is the astonishing vibration and saturation and intensification that he procures ��� theres something sexual in it ��� that I feel I can write like that, and seize my pen, and then I can���t write like that. Scarcely anyone so stimulates the nerves of language in me: it becomes an obsession���.

Woolf was one of the signatories of a letter published in the TLS on January 4, 1923, paying tribute to the French author who had died the previous year (other signatories include Bennett, Conrad, Forster, Gosse, Huxley Scott Moncrieff and Strachey).

The letter appears in the TLS���s ���From the Archives��� item on p34 of this week���s issue (May 27), along with a perceptive review of Du C��t�� de chez Swann by the poet Mary Duclaux, published in the TLS on December 4, 1913.

May 27, 2016

The BBC's religion blind spot

Nicky Campbell on The Big Questions, 2014

By RUPERT SHORTT

Written nearly forty years ago, The Half-Shut Eye by the late John Whale is an elegant broadside with a twofold argument. First, that much television output holds up a distorted mirror to the world; but second, that this doesn���t matter because the medium itself is of little importance. Though a former ITN Washington correspondent, Whale was happier as one of Harold Evans���s chief lieutenants on the Sunday Times. Aware that his highbrow stance could constitute a blind spot of his own, he later acknowledged that only the first of his theses held water.

Faith is one of the subjects which has not been well served by television. This blog is a cautionary tale about the start ��� and likely end ��� of my career as a small screen pundit last Sunday. I���ve lately published a tract of my own, God Is No Thing, which doubles up as a reply to the New Atheists and a defence of Christian belief. Frustrated both by New Atheist stridency and a more general air of condescension among secularists, I set myself the task of explaining in a hundred pages how you can be philosophically and scientifically literate, yet still go to church without leaving your brain in the porch. That, presumably, was why I was invited to appear on The Big Questions, the discussion programme hosted by Nicky Campbell that follows Andrew Marr���s Sunday morning interview on BBC1. A small studio audience sits behind ten or so guests who debate the issue of the week. Last Sunday���s pre-recorded item was entitled ���Did man create God?���

Though promised ���an in-depth encounter with more time than usual��� by a Corporation researcher, I was largely relegated to the role of spectator. Apart from bowling me a googly (���Aren���t religions by definition exclusionary?��� ��� a question almost impossible to answer in a nutshell), Campbell gave me no opportunity to speak at all. Instead, the baton was passed again and again to the shouters and mud-slingers, especially on the atheist side. One of the more constructive non-believers was kind enough to note the oddness of all this in a message to me afterwards. ���Nicky is very uneven-handed in terms of the people he turns to���, this person wrote.

So what points would I have made, given the chance? Here are a few. Yes, of course man has created God to a significant degree. Get over the binary alternatives! It ought to go without saying that much theological speculation and religious practice involves projecting fantasies and guilt feelings into the sky. But that hardly discredits religion as such. What the philosopher Mary Midgley terms ���nothing buttery��� (���We���re nothing but atoms and molecules���; ���We���re nothing but our genes���) is itself highly questionable. Meaning is no less real for not being physical; you don���t shed any light on a poem by examining the chemistry of the ink on the page. And talking of poetry, poets themselves don���t merely draw on their inner resources: they interact with their surroundings. In short, they discover as well as invent. Allied to this stands an awareness at the core of a Jewish or Christian or Muslim world view ��� that since we���re not self-created, we���re answerable to a truth we don���t create.

Not self-created. Though books have appeared with hubristic titles, including Lawrence Krauss���s A Universe from Nothing, it is not possible, in the terms philosophical naturalism allows, to say how anything can exist at all. X is potentially y because x already exists: as Aristotle saw, potentiality is always a function of actuality. No surprise, then, that when Krauss employs the term ���nothing���, it is always productive in some sense. A quantum vacuum is not nothing: it is a relatively empty entity within a structured cosmos. That is why the question whether the universe was created differs radically from musings about fairies at the bottom of the garden. If asked to construct a theological framework from the data of experience, I���d point to three elements: first, an awareness of ourselves as embodied beings with the capacity to grasp meaning and truth; second, the process of seeing our status as a gift prompting awe, gratitude and a heightened sense of ethical awareness; and third, an acknowledgement of that gift as grounded in a reality that freely bestows itself to us.

Some readers might be wondering whether all this amounts to anything more than a solitary gripe. I wish it were only that. The problem is that Nicky Campbell���s lack of balance is equally evident across the BBC. Take a flagship radio programme like Start the Week, which has allowed one atheist commentator after another ��� not just Richard Dawkins, but A. C. Grayling, Steve Jones, Sam Harris, Brian Cox and Quentin Skinner among others ��� to parachute into theological territory without map or compass. I would level the same charge against Andrew Marr, who is also Start the Week���s main presenter, and know that my view is shared within the BBC���s Religion and Ethics department. While not censored entirely, faith-based perspectives tend to be confined to special zones such as Songs of Praise and ���Thought for the Day���.

The unacknowledged assumption here is plain: atheism is the default neutral stance for grown-ups; religious voices, even highly self-critical ones, are biased. (This must be why another major programme, The Moral Maze, contains only one non-atheist on the resident team of inquisitors.) In other words, my experience was symptomatic. The Big Questions: Did man create God? airs on May 29 at 10 a.m., but I fear I can���t recommend it. Television matters hugely. That���s but one reason why it needs to do better with matters of faith.

Return to Utopia

By MICHAEL CAINES

I've possibly mentioned the 500th anniversary of Thomas More's Utopia on this blog already . . . Anyway, this time it's with just two small things in mind:

1) The recording of the panel discussion about Utopia that I chaired at Kings Place recently is now available for all to hear, as an episode of our podcast TLS Voices. As above. It was a great pleasure listening to Matthew Beaumont, Chloe Houston and Nicole Pohl share their thoughts on the subject, although I wish my memory hadn't deserted me at precisely the moment somebody in the audience asked us, quite originally, about John Lyly's play The Woman in the Moon ��� which is set in Utopia.

2) "Visions of Utopia" is now installed in the British Library's Sir John Ritblat Gallery, and is well worth a quick look if you happen to be in the area. . . .

It's a display that manages to be modest and magnificent at the same time. Modest because it fills only three display cases, and is surrounded by textual wonders such as Codex Sinaiticus and Magna Carta. Magnificent because it runs from early manuscripts by More (his "Rueful Lamentation on Death of Queen Elizabeth" of 1503) and Erasmus (his letter to Henry VIII of 1499) to modern descendants such as H. G. Wells's Modern Utopia next to Aldous Huxley's Wells-mocking Brave New World.

You stop on the way at The Blazing World of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, in the form of a fine first edition of 1666, open at her husband's tribute to her "creating Fancy" and "pure Wit". Then there's Louis-S��bastien Mercier's L'An 2440, a hit with English, French and German readers of the late eighteenth century. And a page from J. G. Ballard's Super-Cannes shows that the great dystopian fabulist of our own time once thought better of a character hoping to "knock a ball around the tennis court", and had him "fix a martini" instead. Overall, the emphasis is too secular ��� Utopia being an intervention in current theological debates of the time, apart from anything else ��� but perhaps that comes with the emphasis on historical diversity. My fantasy of a grand exhibition that sticks to More's own time will have to remain, like the Duchess of Newcastle's Blazing World, strictly in my own head.

In particular, if these "Visions" do entice you into the BL any time soon, pray consider the assorted early editions of Utopia and what they imply about the literary and intellectual life of Europe 500 years ago. For More's satirical, visionary book was partly written abroad, first published at Leuven, then Paris, then in various places where there were humanist scholars and printers to appreciate it; the first English translation wouldn't appear until well after More's execution for refusing to subordinate his religious beliefs to his monarch's dynastic/libidinous whims. Is there a moral in that for these referendum-troubled times? There could be, I suppose ��� one to bear in mind, perhaps, as you're reading next week's TLS, in which a symposium of leading cultural figures considers, among other things, the question of what leaving Europe could mean for cultural life on both sides of the threatened divide. . . .

May 25, 2016

The Story Machine: a multidimensional literary event

Sarah Hall reading "Theatre Six"; credit: Neeley and Matt Drown

By ALAN MURRIN

I climbed the stairs of Dragon Hall, home of Writers��� Centre Norwich, to the vaulted Great Hall of this fifteenth-century building, where an audience was waiting for a reading to begin. A woman in dungarees and a knotted headscarf emerged from the wings. She was, we soon learnt, the mechanic oiling the metaphorical cogs of The Story Machine ��� a multidimensional literary event directed by Sam Ruddock for this month���s Norwich and Norfolk Festival. It was her job to introduce us to the writer Sarah Hall, who ��� herself dressed in surgical scrubs ��� read her story ���Theatre Six���, a dystopian vision of healthcare in the near future, in which a doctor���s faith in her vocation is threatened by a new political world order. A woman then entered dragging a wicker mat with an alabaster leg lying on it. She was quoting lines by Carol Ann Duffy from the poems ���We Remember Your Childhood Well��� and ���Mrs Lazarus���. If I had followed her to the garden at the back of the building, I would have heard a story by Jarred McGinnis, the founder of the literary variety night The Special Relationship. In his story ���Charles III���, the Poet Laureate has been hung, drawn and quartered, and the limb that had just passed me represented her remains. . . .

It���s not always clear that arts festivals know what to do with literature other than the pleasant yet obvious things, like interviewing authors and hosting book signings. Joyous in tone, international in scope and direct in its confrontation with serious issues, The Story Machine offered something decidedly different, without any of the po-faced posturing that can sometimes make such events feel like a chore for all involved. (And its success, incidentally, hints at what Writers��� Centre Norwich could achieve if the funding targets for the next stage of its development are met. [http://www.writerscentrenorwich.org.uk/supportus.aspx]).

I decided to forgo the ritual dismemberment in the garden to attend another of eighteen delights on offer over the next three hours: ���Situations���, a collection of video essays produced by the writer Claudia Rankine and her husband, the filmmaker John Lucas. The films were based on Rankine���s award-winning collection of essays, vignettes and poetry, Citizen: An American lyric (reviewed in the TLS of September 18, 2015); and they focused on a shopping mall, a train, Hurricane Katrina and Zinedine Zidane���s infamous World Cup Final headbutt. The footage of Zidane was slowed down to such an extent that, even as the footballer squared up to his opponent, it seemed that the blow might never land. Each of the films dealt with issues of racial identity and prejudice, and Rankine���s words stuck in my mind after I had left the room: ��� . . . In a landscape drawn from an ocean bed, you can���t drive yourself sane ��� so angry you are crying. You can���t drive yourself sane . . . ���.

I made my way to the bar. There were six cocktails available, each relating to one of the events. I was about to attend a reading by Kevin Barry, so decided to have ���A Cruelty��� ��� a drink devised by the man himself and named after the story he would read later that afternoon in the garden. First, though, he was reading one called ���Roethke in the Bughouse���, in the Great Hall. This, we discovered, was about Theodore Roethke suffering a breakdown during a trip to the island of Inisbofin, and his subsequent treatment in a psychiatric hospital.

In the garden, lunch was being served. You could choose a story to be served with your vegetables and couscous: ���The Reader��� or ���The Writer��� by Etgar Keret, folded origami style. People had already begun to position themselves expectantly in the glass atrium beside the entrance to ���The Electrification Trilogy���, for which places were limited. Twelve of us were led underground. We descended a narrow staircase to a low-ceilinged cavern lit only by candlelight. Keret told us the tale of how his parents met, a serendipitous encounter that involved his father being arrested for pissing against the western wall of the French embassy in Tel Aviv. Next we were led to a lower room where an actor performed ���Electrification��� by the Soviet satirist Mikhail Zoshchenko. A married couple have electric light installed in their apartment, and it exposes the full extent of their poverty. With no money to improve their circumstances, the husband bemoans their fate: ���Light���s all very well, brothers, but it���s not easy to live with���. As we were led back into daylight, the trilogy ended with the sweet story of how Keret and his wife protected their son by playing a game that distracted him while they waited out an air-raid siren on the outskirts of Tel Aviv.

Everyone congregated in the Great Hall once more, for the final act. There was a simple and charming close to proceedings: Anna Metcalfe read her story ���Still���, with a drawing of a plum tree projected on to the wall behind her, changing as the story progressed. It was the story of a widowed man and his son who take a photograph of the same tree every year as the last leaf falls from its branches. And it was beautifully done. Other festival producers should take note.

Anna Metcalfe reading "Still"; credit: Neeley and Matt Drown

May 24, 2016

On the trail of a Chinese typewriter

By JEFFREY WASSERSTROM

���How far is Irvine from the Huntington Library?���

This was the first question my friend Tom Mullaney, a fellow historian of modern China, asked me in 2012 when I invited him to come down from Stanford to speak at my campus. I initially found this curious, since the Huntington, which is about an hour up the freeway from me, has wonderful manuscript holdings, but few if any that deal with twentieth-century China; and while its gardens are world famous, Tom had never struck me as having more than a casual interest in plants. The mystery was soon resolved, however, when he explained that its collections happen to include one of the objects that had come to obsess him ��� Chinese typewriters.

In the end, he accepted my invitation. This meant Irvine faculty and graduate students were treated to a splendid talk on both the history of Chinese typewriters and common misconceptions about them (that they need to be gigantic devices with thousands of separate keys, one for each character, for example). This was half of that also included a presentation by me on the Chinese Boxer Crisis of 1899���1901. The highlight of his trip down south, though, came when we went up to the Huntington, where he gave the same basic talk but with a nice added twist: the curators were kind enough to bring their prize Chinese typewriter into the seminar room.

I think it���s safe to say that Tom is still obsessed with Chinese typewriters, objects he collects as well as studies, but it���s clearly an obsession that is not just draining his bank account but paying off in many ways. He has published articles on the topic, including one that makes a persuasive case for a version of predictive text having an impact in China well before it became important in the West. An interview I did with him for the Los Angeles Review of Books has recently drawn positive attention from the educational arm of National Geographic. His views on the pros as well as the cons of languages that rely on characters rather than alphabets have been spelt out in a commentary for the online edition of Foreign Policy magazine, which includes allusions to both Hegel and Lisa Simpson. MIT Press has accepted his book manuscript on the Chinese typewriter, while also agreeing to publish a sequel dealing with computers. In the latter, he will elaborate on his claim that, far from creating major obstacles to modernization as has often been asserted, using characters can be an advantage for a language in the digital age.

In addition to all this, his obsession has led to an exhibition that is currently up at Stanford���s East Asia Library, where I had a chance to see it earlier this month (it will soon travel to other sites). It is a modest-sized but richly varied exhibition, with two Chinese typewriters and a video loop showing documentary footage that illustrates how these machines are used (some allow users to combine commonly used elements to create characters, while others employ a retrieval system that allows the typist to select from a large pool of individualized full characters). Display cases provide not just information about and objects from China but also related materials associated with Japan and Korea. The exhibition also offers insights into the strategies that make communications systems originally developed with alphabets in mind work for characters. Visitors learn, for example, of a telegraphy system developed in 1871 which linked individual characters to unique four-digit numerals that could then be tapped out in Morse code; and of pinyin romanization-based techniques for rapidly inputting text on digital devices. On display is everything from early handbooks for Asian typists to a VHS box for a television movie entitled The Chinese Typewriter, which starred Tom Selleck and had nothing to do with the eponymous object.

It is interesting where obsessions can lead scholars, and to be honest I should note that, while I wanted to see Tom���s exhibition from the moment I heard about it, I���m not sure I would have if one of my own scholarly obsessions hadn���t come into play. While Tom���s finished his Chinese typewriter book, I���m still writing the one about the Boxer Crisis that was in its formative stages when he and I did our presentations in Irvine four years ago. The main reason I went up to Stanford earlier this month was to find out all I could about two students who attended that college in the 1890s, headed to Asia soon after graduating and marrying, and were swept up in that event, which began with an anti-Christian uprising and ended with an international invasion and then military occupation of North China. In the middle of 1900, these two young Americans feared for their lives, when they and other foreigners in Tianjin were held captive by a joint force of Qing Dynasty soldiers and Boxers ��� messianic militants who were called that in part because of their use of martial-arts techniques. The Stanford graduates and newlyweds, whose first names were Herbert and Lou, not only lived through the ordeal but went on to become occupants of the White House. For their last name was Hoover.

I knew that, among the many other things held at the Hoover Institution located on the Stanford campus, were, not surprisingly, some materials about the man for which it is named and his wife ��� the half of the couple whose experiences in China particularly intrigue me. I was not seeking a look at an object, but rather trying to learn more of the story behind an artefact that had come to exert a powerful hold on my imagination: a photo taken in 1900 that shows Lou Henry Hoover wearing a dark skirt, a white blouse and a cowboy hat, leaning against the giant wheel of a small mobile canon.

While there are some relevant materials about the Boxer Crisis in the Hoover Institution���s archive, the most interesting documents, such as an unpublished manuscript by Lou on her time in China, are held instead at the Hoover Presidential Library, which is in Iowa. I am now trying to figure out when I can make a trip there on what I���ve come to call my ���Study the Boxers, See the World��� tour. (Next stop: London, where I���ll be combining book launch events for The Oxford Illustrated History of Modern China, a work I edited, with visits to archives with holdings relating to Lao She. A Beijing native best known in the West as the author of Rickshaw, Lao She taught at the precursor to SOAS in the 1920s, just over two decades after his father was killed by foreign soldiers who had come to China���s capital to suppress the Boxers.) I doubt my time in Iowa will include a side visit to anything as intriguing as Mullaney���s Chinese Typewriter exhibition. You never know, though, what you will find, or have an opportunity to do, while following a scholarly obsession.

May 21, 2016

Tom Stoppard, to the life

Tom Stoppard, 2013; copyright Peter Tarry/Times Newspapers Ltd

By CATHARINE MORRIS

���Biography adds a new terror to death.��� It was Oscar Wilde���s line that sprang to Tom Stoppard���s mind when he was asked by Hermione Lee about his own ���suspicions about biography��� at the London Library���s recent Words in the Square festival. We were in a marquee holding our champagne flutes, and their talk ��� an amiable conversation between a biographer and her subject ��� was part of the celebrations for the Library���s 175th birthday. Stoppard is the Library���s President, and has been a devoted member for some forty years.

Lee gave as evidence of Stoppard���s ���suspicions��� the ���ruthless and ridiculous questing biographer��� Bernard in Arcadia. ���You have been quoting my characters rather than me,��� Stoppard replied, ���which is not entirely unfair.��� He told us that he had that morning started reading a book by David Kynaston which features an ���abject, furious��� letter written by Kenneth Tynan ���when he was seventeen���. It had brought to mind ���every kind of consideration to do with things you���d forgotten yourself being disinterred. But I think it���s all fair, and I would like to be the kind of person who is completely indifferent to such things���. When Lee suggested that there might be more to his scepticism than that, he conceded that he had a lively sense of perspectives differing from one another ��� a ���famous if not notorious��� aspect of police witness statements that has also provided what is ���almost a sub-genre��� in fiction and in film.

So what can biography offer if not the absolute truth? Stoppard quoted W. H. Auden: ���A shilling life will give you all the facts���.���But one also reads a biography because it���s well written.��� (When the two things are combined, a book may be considered ���one of the great biographies���, he said ��� Richard Ellmann on James Joyce, for example.) And what is the advantage, Lee wondered, in using real people as characters in plays ��� A. E. Housman, James Joyce, Lenin, Shakespeare . . . . ���One isn���t writing biography in a peculiar form . . . . It is simply ��� or much more clearly to me ��� that the person who stimulates certain ideas and provokes you in certain ways happened not to be a character of fiction.���

Lenin featured in another fruitful line of questioning ��� about what it���s like to watch or re-read a play you wrote many years ago. Stoppard declared himself ���very cold-blooded about that, actually���, and was reminded of something said by George Devine, who ran the Royal Court Theatre in the 1950s and 60s ��� that ���all problems are technical���. He described a problem he is currently having with Travesties (a play first performed in 1974), which will be back in rehearsal in August. In it, Mrs Lenin ���quotes at some length from everything Lenin ever said or wrote on the subject of art���. Stoppard has come to conclude since writing the play that ���Just because it���s interesting, doesn���t mean it���s motoring the story���. ���Are you going to change it?���, asked Lee. ���You know,��� said Stoppard, ���the director is waiting for the answer to that question.���

That led to a story about something that happened the day before Travesties opened for the first time. One of the characters had a monologue that lasted about ten minutes, but the actress had a bad throat, so they used only the first paragraph, and Stoppard discovered that he preferred it that way. When the play was later rehearsed in French for the first time, the director rejected Stoppard���s suggestion that the monologue be cut in the French too ��� ���Oh, no no! C���est magnifique!��� ��� and reported, once the play had opened, that it had gone down extremely well (���Incroyable! Parfait!���). Stoppard went to see it for himself, and found that ���it was exactly as he said ��� she did the entire speech; you could have heard a pin drop ��� but he never actually mentioned that she was naked���.

Stoppard was able to add, once the laughter had died down, that this story demonstrates how ���every moment in a play is some kind of equation . . . . In other words, the speech can be just the right length if you���re looking at something that interests you . . . . And a speech a quarter of the length can be too long if there are other things in the equation which aren���t balancing���.

There were lots of nice insights like that:

���I don���t think one ought to know too much about the play as it will be when it���s finished".

And:

���Although theatre is a literary art form in many respects, it���s not wholly so . . . and it���s much more understandable as . . . an attempt to describe something which hasn���t happened yet���.

When speaking of talent as the sine qua non of writing of an artistic kind, Stoppard added that ���when I say talent, I don���t mean skill. I mean something which nobody understands���; and, on being asked whether he felt it a writer���s duty to be socially and politically engaged, he said that this was ���actually quite a difficult, troubling question���:

���Cyril Connolly said the only duty or purpose of a writer is to write a masterpiece. Nothing else matters. The masterpiece could be about the tulips in St James���s Square. And yet, and yet: so many great works of art have survived by the virtue of what they are . . . being intellectually engaged with rather than with some intrinsic aesthetic".

Stoppard's dry humour was never far from the surface. He said that after his assistant started typing up scripts for him in the mid-1970s (it had taken him a while to get over his shyness about it), he ���started putting her surname into what she was typing just to wake her up���. Her name occurs in everything he���s written since then, ���and she now is becoming very critical about what kind of role she is being given���. After describing the social timidity that was part of the personalities of both Isaiah Berlin and Turgenev (two figures who loom large in Stoppard���s intellectual biography), he said that he saw it in himself, too. ���Everybody thinks I���m really, really nice, don���t think I don���t know it. They think ���Oh, he���s so nice!���. They have no idea what���s going on . . . . I���m a fairly benign person, but I���m quite aware that I am making an impression on people I meet, and I���m not careless about the kind of impression I leave.���

That���s not to say that he thinks about himself a lot ��� by his own account quite the opposite, in fact: ���The last thing that occurs to me to do is to, as it were, account in any way for the nature of my work . . . by picking over my charmed, happy, bumpy ride to this point. Perhaps I should be more interested in myself, but I really am not, I really am not���. What a good thing, then, that Hermione Lee is.

May 19, 2016

English as she isn't spoke, part 3

Orient Express, Paris, April 29, 2016 (ELLIOTT VERDIER/AFP/Getty Images)

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Is it time for an update on station announcements? If the rail companies ran a faultless service in Britain the announcers would have an easy job of it. Sadly, this is very far from being the case, and announcers have to devise ever more baroquely phrased explanations for delays and cancellations. I know I���ve written about this subject more than once before but, to a captive auditor it���s a gift that keeps on giving or, as the announcer would no doubt have it, a donation that continues to donate.

I���m convinced that the English language is being stretched in new and unpredictable ways across station concourses up and down the land. And not necessarily in a good way.

���Please be advised that this train will now be subject to a platform alteration and will depart from Platform . . .��� is a common one. Does it sound like standard English to you? No, nor me. How about ���This train will now be departing from Platform . . . ���? Clearer, more concise and gets rid of the redundant genteelism ���please be advised . . .".

���In reaction to��� has become linguistic orthodoxy too. As in: ���This is in reaction to overrunning improvement in the St Albans area���, or ���This is in reaction to an earlier cable fire in the Vauxhall area��� (incidentally, how do cables catch fire?).

Then there are the deliberately unclear announcements, such as ���Due to conductor shortages [as in food shortages?], some services may be altered���. For ���altered��� I sense they mean ���cancelled���. ���This is due to a currently unidentified reason which is under investigation���, meanwhile, just sounds mysterious.

���Short formation��� has also become standard phrasing: ���We are sorry for the short formation of this train���. Or ���This service is short-form this morning, and the first-class accommodation has been declassified��� (like an official document?). On other occasions, we are informed that ���First class has not been declassified���. In other words, if you are travelling in first-class without a first class ticket, you will be liable to a penalty fare payable to the ���on-board Revenue Protection Officer���.

I continue to enjoy announcers��� use of the word ���accommodation���. We are often told ���We are sorry to inform you that there is no first-class accommodation on this service today���, as if it���s the Orient Express steaming its stately way across the Continent rather than a humdrum commuter train out of London.

���Please note that this service has been reported as full and standing only���: it���s always good to get an advance report on the train you���re about to board. Adds a frisson to the experience. ���The service on Platform 2 is the replatformed service for London Bridge���. Replatformed? It���s a new one on me. ���The 8:34, originally due to depart from Platform 4 . . .". Strange use of ���originally���, or am I being over-pedantic? It���s hard not to be as the delays and cancellations pile up.

May 17, 2016

Old Sport and gin rickeys: The Great Gatsby at Senate House

By BENJAMIN POORE

���Can���t repeat the past?���Why of course you can!���, ran the tagline. Masterminded by Professor Sarah Churchwell, the Living Literature series aims to immerse people in the worlds of our favourite literary works ��� starting the week before last with The Great Gatsby. We were promised a party, and what we got was a relatively free-form evening of pop-up talks, displays, music, cocktails, silent film and costumes in the art-deco surroundings of the University of London���s Senate House in Bloomsbury. ���This is not a lecture���, Sarah Churchwell declared from the grand staircase in the lobby, which was bathed in the slightly uncanny green glow that lingers throughout Scott Fitzgerald's novel. Dressing up was mandatory.

Gatsby is well known for its synaesthesia: Nick Carraway���s famous description of the ���yellow cocktail music��� of the party springs to mind. But this tumult of both seeing and hearing ��� the excitement and confusion of sensory overload ��� is an element of the novel that was amplified at the event. Partly following the lead of Secret Cinema and Punchdrunk, actors (from Punchdrunk, in fact) wandered about encouraging people to get into the spirit of the Jazz Age. This was an exercise in meticulously researched precision: posters, billboards and newspaper articles were taken from the exact historical moment of the novel's setting in 1922, and accompanied by excerpts from the novel. Text and image were given to us in myriad forms, including movie reels of New York from the 1920s, along with sound recordings of Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald. Even the recipes for the canap��s were taken from the period (though the spread was not quite as lavish as Gatsby���s, with its ���glistening hors-d���oeuvre, spiced baked hams crowded against salads of harlequin designs and pastry pigs and turkeys bewitched to a dark gold���).

The spirit of the Jazz Age was, of course, gin, in the form of classic 1920s cocktails ��� notably the gin rickeys mentioned in the novel (1 1/2oz gin, lime juice, soda water, lime garnish, mixed in a highball with ice). Jay Gatsby���s bootlegger background was part of the evening too: to get hold of the gin or bourbon for your desired drink, you had to sidle up to one of the costumed characters carrying a basket of daisies and wait for them to produce a miniature. The London Gin Club had even brewed a special batch of ���bathtub gin���, based on Scott Fitzgerald���s own attempts at home-distilling, which was a cheerful 69 per cent proof. There was live jazz, of course, and a special section devoted to two historical fragrances concocted by the parfumier Sarah McCartney ��� the small atomizer that I left with contained ���Old Sport���. The researchers and graduate students who work on the period were happily milling about to discuss their work.

The gin and perfume were more than gimmicks for extracting cash. Drunkenness is very important in the novel, and the act of drinking punctuates key scenes. Until Nick Carraway finds something better to do or someone to talk to, he slopes off to the cocktail table, ���the only place in the garden where a single man could linger without looking purposeless and alone���. The rug in Gatsby���s mansion is ���wine-coloured���, a mock-Homeric gesture that I suppose must paint Gatsby as a deluded Ulysses, presiding over a savage race of Long Island socialites, living the epic of his own life. It is the tragedy of the characters in the novel that they believe the party doesn���t have to end.

Propped up around the event���s two main rooms, and in the programmes, were various enlarged pages from the New York newspapers of the summer of 1922 (the Tribune, Evening World and Herald Tribune, among others) with fashion tips and sketches of the latest trends in women���s haute couture (���The Charm of Studied Simplicity���; ���Toilettes for Midsummer Days���). Carraway notes at the end of The Great Gatsby that Jordan Baker, who is dressed for golf, ���looked like a good illustration���. Dressing up, whether for a party or not, reminds us that, in both Gatsby���s world and our own, identity is a fiction anyway, and the images we use to re-imagine ourselves are as flimsy as they are seductive.

This Living Literature event proved a clever means of having fun with a novel that has gone too many rounds on the A-level literature syllabus. What else might be amenable to this treatment? Novels with highly textured sense-worlds ��� which is to say, lots of eating and drinking. Gatsby seems to work so brilliantly partly because it is a novel about trying to close yourself off from the outside world; playing make-believe with it was always going to sit well. There is the possibility, Sarah Churchwell told me, of doing Marcel Proust next year. Expect champagne and madeleines ��� though after the bathtub gin, I might play it safe and stick to the lime-blossom tea.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers