Peter Stothard's Blog, page 5

June 30, 2016

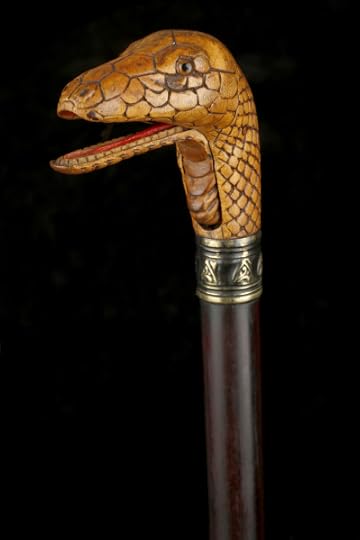

The work and legacy of Aby Warburg ��� born 150 years ago this month

Aby Warburg

By ALESSANDRO SCAFI

"He would have loved today, I am quite sure. He would have been proud, he probably would have been embarrassed . . .". These are the words of John Prag, Professor Emeritus of Archaeological Studies and grandson of Aby Warburg ��� the German art and cultural historian who founded the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg in Hamburg. Prag was thanking David Freedberg and Claudia Wedepohl, the organizers of a three-day conference held at UCL Institute of Education in London and hosted by the Warburg Institute (where I teach Medieval and Renaissance Cultural History) to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Warburg���s birth on June 13, 1866.

More than thirty distinguished speakers and an audience of 1,200 people from all over the world gathered over two-and-a-half days to pay tribute to and discuss Warburg���s "work, legacy and promise". Prag said that Warburg would have been thrilled by today���s technology. There is no doubt that he took a close interest in the momentous industrial and technological advances made during his lifetime. He was excited and fascinated by air travel, for example; but he also warned of the impact the telephone and telegraph would have on our sense of distance, and "the space for reflection" ��� the precious time in which we formulate a measured response to anything that prompts a reaction. Thinking of photography, Warburg feared that the human mind was in danger of being swamped by a sudden profusion of images. What would he have made of the spread of the internet and the omnipresence of mobile phones? The question was hanging in the air when W. J. T. Mitchell compared the simultaneous display of images in Warburg���s famous atlas of images, the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, with the world wide web.

Warburg was deeply aware of the creative tension between what he termed classical "Athens", the realm of reason, and Hellenistic "Alexandria", representing, in his view, irrational impulses and the irresistible allure of magic and superstition. Though Warburg called upon Athens to subdue Alexandria, he acknowledged that the reasonable city was ever-ready to be reconquered by its irrational counterpart. Warburg believed that the energy produced by this polarity propelled the transmission of cultures across time and space, and lay behind the survival of the classical tradition. Kurt W. Forster reminded us that the fascination with "energy" was shared by many of Warburg���s contemporaries, while Cornelia Zumbusch recalled the long history of the idea that art itself is a form of energy. Intrigued by the universal mechanisms that engender the recurrence of images in the human mind, Warburg pioneered the interdisciplinary, cross-cultural exploration of symbols that informed the arrangement of his personal library in Hamburg. In 1921, this became a research institute; in 1933, under threat by Nazi power, it moved to England; and in 1944, it was incorporated into the University of London.

Now a leading international research centre for the study of cultural history, the Warburg Institute developed from Warburg���s book collection. The conference���s declared aim was to revive and promote Warburg���s vision in the world of scholarship, but also to highlight its relevance in contemporary issues and debates outside academia, and its potential significance in the future. The objective was brilliantly met. Topics included epistemology, serendipity, morphology, 1970s art exhibitions, hieroglyphs and snails. Important figures discussed included Charles Darwin, ��douard Manet, ��mile Durkheim, Sigmund Freud, Wolfgang Pauli and Erwin Panofsky. We learnt about Warburg���s antecedents and followers, his times and places. Offering significant advances in our knowledge of Warburg, the papers delivered represented a rich variety of viewpoints, spanning cultural history, media culture, aesthetics, the history of science, art, philosophy and literature.

In his introductory remarks, Freedberg discussed not only Warburg���s concern with the effects of technology and the proliferation of images on human reflection and self-awareness but also his belief in the importance of the comparative study of human cultures and religions; and his vision of a comprehensive cultural science, a Kulturwissenschaft that transcends academic boundaries, embracing anthropology, psychology, politics and biology. Freedberg also noted that, approaching Warburg���s notion of Nachleben, in particular the "afterlife" of antiquity, "we should not just be studying the Nach in Nachleben but more importantly the Leben in Nachleben, the life that remains in cultural forms across time". The idea is fascinating. Why do human creations from past ages remain vital? Is there a primordial language of emotional feeling that safeguards expressive gestures across the centuries (Warburg���s Pathosformel)? Finally, Freedberg stressed the importance of what Warburg termed Br��ckenbau ��� "building bridges" across cultures and between the arts and sciences. It was a fitting birthday tribute to the grandfather of a whole way of thinking about human cultures that so many came together in London to build bridges between disciplines, forging living connections between past, present and future.

John Prag, Professor Emeritus of Archaeological Studies

Professor David Freedberg, Director of the Warburg Institute

The Afterlife of the Kulturwissenschaftliche bibliothek Warburg: The emigration and the early years of the Warburg Institute in London by Uwe Fleckner and Peter Mack will be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS.

June 28, 2016

Public religion, private religion

Professor Tariq Ramadan; credit: LSE (all rights reserved)

By JAMES WALTERS

Queen Elizabeth I ended decades of bloody religious warfare in England with the memorable resolution that she ���would not make windows into men���s souls���. It���s a maxim that encapsulates many of our modern British assumptions about the place of religion: un-interfered with in private, tempered down in public. Continuing in the line of female icons who balance British tenacity and religious reserve, Downton Abbey���s Dowager Countess echoed the sentiment in a comment on principles, ���They are like prayers, noble of course, but awkward at a party���.

But the neat categorization of religion���s appropriate role in both public and private life are being radically unsettled in Britain today, partly through the erosion of the Anglican expression of Christianity (more than 20 per cent of British churchgoers now attend new, Pentecostal or independent churches), but primarily through the growth in size and impact of British Islam. The number saying they are Muslim in the UK census rose by over a million between 2001 and 2011.

The ways in which this is challenging accepted British norms about the place of religion were explored in two recent events at the London School of Economics to mark the launch of a new blog on Religion and the Public Sphere. In the first, Professor Gwen Griffith-Dickson argued that in recent years, under the banner of counter-extremism, the state has indeed sought to make windows into men���s souls. The private is no longer the inviolate domain of faith. Professor Griffith-Dickson highlighted the growth in belief among legislators of the primacy of religious ideology in driving radicalization rather than other social or psychological factors as grounds to breach this boundary. This has led to the view that even extremist views that disavow violence are a legitimate matter of concern to the state. Certain doctrines have, it would appear, become thought crimes. The traditional British view that a person���s religion is her own business until it has an impact on others has been overturned. For Muslims at least, private belief is a public matter.

Professor Gwen Griffith-Dickson; credit: LSE (all rights reserved)

The second event, with Professor Tariq Ramadan, concerned the shift that is of more vocalized public concern and often fused with opposition to migration, and that is a renewed presence of religion in the public sphere. As much as racial diversity, it is the presence of confident manifestations of different faith traditions that unsettles many in the UK, and none more so than Islam. Once hailed as the Muslim Martin Luther, Professor Tariq Ramadan said much to challenge a simplistic opposition between Islamic practice and British public life. He hinted at the need for some radical contextualization of the historic Muslim texts, not least in relation to women���s and children���s rights. But the heart of his lecture was a protest against the pressures to fit in with British religious compartmentalization by becoming ���invisible Muslims���. He highlighted the bigger picture of a religiously and culturally pluralistic society where a bland liberal consensus will no longer hold. Values long assumed by Western elites to be universal and self-evident are simply not shared by everyone, and no amount of Governmental pressure to assert ���British values��� is going to change that.

For such pluralist societies to hold together, we need more than pragmatic discussion about how we can live together. Ramadan called for dialogues ���at the centre of what we believe���. Western culture has become very thin, and to move beyond shallow tolerance for each other (a tolerance whose shallowness is all too easily exposed) we need conversation about our fundamental philosophies of life and death, meaning and purpose. In other words, we have got to bring religion out of the confines of the soul and into the public sphere. We have to hear about what matters most to people in conversations that aren���t immediately framed by programmatically secularist assumptions.

This challenging of the public/private segregation of religion in British life raises a number of questions about the terms of these conversations. If socially conservative religious positions are now viewed by the state with suspicion, people will refuse to be honest about them in the public sphere. If religious ���visibility��� in the public sphere is always feared as an attack on liberal values, we will remain blind to ideas and practices that might bring value to our common life. But if secular institutions such as the LSE can now be a platform for such conversations, we might yet avoid the return to the ���Wars of Religion��� that the doom-mongers predict.

The Revd Canon Dr James Walters is Chaplain and Senior Lecturer in Practice at the London School of Economics.

June 27, 2016

Ten things I hate about my country

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

1) Our national anthem ��� it���s surely the worst of all: dull, dispiriting and banal. Watching the European football tournament and the teams lining up before the games I can���t help feeling how lucky the Welsh are to be spared it (the Northern Ireland team are not so lucky). And of course the Welsh anthem is truly stirring.

2) Our obsession with the royal family, who, as far as I can see, don���t do very much that���s useful.

3) The mindlessness that takes over the nation every time the English football team ��� Engerland ��� is involved in a football tournament, in which they nearly always underperform.

4) The UK���s geographical shape ��� it���s a mess.

5) People referring to ���our national poet���, as the Brexiteer MEP Daniel Hannan did on the radio the other day.

6) People talking of the British parliament as the ���mother of parliaments��� in a meaningless way. (I also recently heard somebody, again on the radio, refer to Britain as the ���birthplace of democracy���.)

7) The fact that I have to think about whether I���m from the UK or Great Britain when I���m filling in a form. I don���t like either appellation. It���s so much simpler in other European countries.

8) Our parliamentary system, which is a mess, as we���ve seen in the past few days.

9) Deluded notions of the UK (GB?)���s world supremacy in all sorts of fields where we've long ago been overtaken by other countries.

10) The politics of Michael Gove, Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson.

June 24, 2016

Retrospection at the Holland Festival

The Walking Forest �� Aline Macedo

By SAMUEL GRAYDON

I recently went to Amsterdam for the Holland Festival (which runs until June 26). It advertises itself as ���showing innovation in art���; it was to my surprise, then, that all of what I saw insisted, in a variety of ways, on retrospection.

Looking back does not necessarily mean that innovation is lacking, of course, as was shown by Mark Cousins���s film about atomic power, Atomic: Living in dread and promise, compiled from public-service broadcasts, stills, documentaries and interviews. An informative work that dragged you into a mindset of the past, it made you reconfigure your understanding of its subject. The film was perhaps not as strong in narrative as Cousins suggested in a discussion before the screening of the film, but it was offhandedly threatening, thanks partly to Mogwai ��� the Scottish post-rock band; they were commissioned to write the soundtrack to the film, and performed it live. Their ambient and droning music nicely complemented the film's explorations of the devastating and the healing potential of the atom.

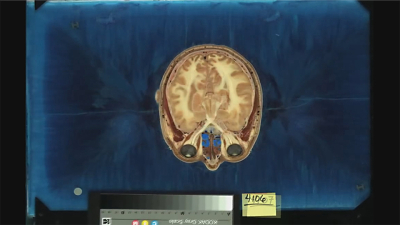

Brain scan; a still from Atomic by Mark Cousins

Atomic was greater than the sum of its parts ��� Cousins's direction was subtle and respectful. In his interview, Cousins said that he believed that ���good storytelling should take your hand and walk with you to begin, and then it should let it go���. I'm sorry to say that, elsewhere in the Festival, I got a bit lost on occasion. Nowhere did I want a friendly guiding hand more than during Christine Jathay���s The Walking Forest, a ���video and theatre installation��� inspired by Macbeth. Jathay intended to make members of the public think about their part in oppression, and what they would do if a real Macbeth came to power. We were spectators, free to wander around as we pleased, but we were actors too. About twenty of us were wired up with earpieces, and we had to do as we were instructed ��� at times we were given mundane tasks such as ���stand by the women at the bar���; at others they had a more exotic flavour: ���feel inside this dead fish filled with fake blood to find two teeth���. There was a free bar, which people made understandable use of; I was given ten euros (covered in fake blood, of course), and ten of us had to (nearly all rather drunkenly) read lines from Macbeth into a microphone. Julia Bernat (the only actress involved in the installation, playing Lady Macbeth) wandered around naked, before getting dressed, pouring water over herself and crawling like a fish across the bar. She then delivered a diatribe on the crookedness and injustice of world politics, lying motionless on the floor. All the while, screens, which eventually moved across the room so as to hem the audience into a corner, informed us about forced migration, corruption, dictatorship and violence inflicted on people by their governments. I seem to remember a semi-naked man wearing a boar���s head, as well.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, my thoughts did not immediately turn to my role in mechanisms of power and oppression.

The problem was that, had I not had any information about Jathay���s intentions before I saw The Walking Forest, it would have made no sense at all (in fact, I couldn't make much sense of it even with the information). I often run into this situation; if I find myself reading the placard next to an artwork more than I actually look at the artwork, it's usually a bad sign.

The Walking Forest �� Aline Macedo

I had similar trouble with a film by Julian Rosefeldt, specially commissioned to accompany an excellent performance of Haydn���s oratorio Die Sch��pfung (The Creation). This film was meant to be antithetical to the music (���if the music evokes a babbling brook, then perhaps you���ll see a dried-up riverbed on screen���) ��� a response, not an interpretation. Whereas in Haydn���s piece, humankind is presented as the height of God���s creation, in Rosefeldt���s film the species has brought about its own destruction by striving at technological advancement.

Once again, I can only make these comments because of the festival press pack. The audience spent an hour and a half looking at aerial views of deserts, the abandoned Atlas Studios film sets and the industrial ruins of the Muir Valley, shot in slow motion with men in white overalls wandering aimlessly around. There was also footage of dogs mating. The landscapes were immense, beautifully filmed and wonderfully colorized, but even so, there is only so much slow-motion desert one can take.

Much more successful, in my opinion, was the Dutch National Opera���s production of Tchaikovsky���s Pique Dame, directed by Stefan Herheim. It was my first acquaintance with the work, and I found it rather awe-inspiring as played by the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and conducted by Mariss Jansons ��� with a powerful performance by Alexy Markov as Count Tomsky. At one point, the chandelier turned into a huge swinging thurible, pouring smoke onto the stage. With the striking black-and-white costumes, the austere but grand sets and the cold lighting, Herheim drew out the oppressive atmosphere implicit in the opera, aided by Misha Didyk���s paranoid and aggressive portrayal of Hermann. Having said that, even though I did not know the opera, I could tell that Herheim was introducing a novel twist that, unfortunately, was not quite paying off. He wanted to explore how ���Tchaikovsky���s unspeakable homosexuality and passion rises through the music to the surface���. And so during the sublime overture, the curtain rose on Tchaikovsky reclining in an armchair while a scantily clad Hermann rose from his knees, lifting his head from the composer���s crotch. Tchaikovsky then proceeded to die, and remained on stage for the entire performance, ���conducting��� his fellow performers and playing the piano. Great pieces of art can be interpreted in different ways (indeed, as Auden had it in his essay on reading, being read in a number of different ways is one of the signs that a work actually has merit), but this was not simply interpretation; it was imposition.

Perhaps I am being facile to suggest it, but sometimes a piece does not need reinterpreting, but simply rereading.

Die Sch��pfung (The-Creation) �� Wonge Bergmann

June 21, 2016

A song for Sorley

By MICHAEL CAINES

Robert Graves reckoned that there were three poets of importance killed during the First World War: Wilfred Owen, Isaac Rosenberg and Charles Hamilton Sorley. The last of these was the youngest, yet also the first to die, by sniper's bullet at the Battle of Loos in October 1915. And he was a captain by then, at the age of twenty.

Neil McPherson tells Sorley's tale in his new play It Is Easy To Be Dead ��� in verse, prose and song ��� at the Finborough Theatre. It begins with Sorley's parents (movingly played by Jenny Lee and Tom Marshall) receiving the worst possible news, but finding a way to commemorate him: by preparing his poems for publication . . . .

Many grieving parents of literary-minded victims of war had the same sort of response. Publication meant remembrance. "Just privately . . . for friends and family", says Janet Sorley (as McPherson calls Sorley's mother Janetta) to her unconvinced husband William. "Everybody is doing it."

In reality, the Sorleys worked quickly: TLS could review their son's posthumous collection Marlborough, and other poems in February 1916. A third edition in December that year with added "illustrations in prose", that seemed to shed welcome light on the poems and the author's personality, justified a further review. And when Sorley's letters appeared in print three years later (his parents had deliberately delayed publishing them until the war was over), the TLS's anonymous reviewer could point out the most "remarkable quality" of Sorley's personality ��� his "exuberance" ��� as well as his promise at public school, his "delightfully amusing" letters from Germany (where he spent several months before and during the outbreak of war) and his astute reservations about Rupert Brooke. He also reservations about his own country. "I hate Britons with a big big B", he once wrote. Not Country in the big C sense but country in the Richard Jefferies sense was more to his taste.

All of these aspects of this attractive figure in It Is Easy To Be Dead. Alexander Knox makes a suitably exuberant, impish Sorley, pattering out the stories of his German travels. He transforms, over the evening's course, from the boy reciting "The Song of the Ungirt Runners" as he runs (and looking like an extra from Chariots of Fire while he's at it) to the charming, camp young fellow observing the Germans (and falling in love with one), to the soldier who names his school friends as their photos ��� and wartime death dates ��� flare up on the wall behind him. Even the idolized Brooke is displayed in the same way, as Sorley criticizes him: "He is far too obsessed with his own sacrifice".

Nothing could be further from that spirit of self-obsession than the poem by Sorley from which McPherson takes his title, "When you see millions of the mouthless dead": "None wears the face you knew. / Great death has made all his for evermore". Neil Corcoran, writing in the TLS in 1986, saw this as "Owen-like" verse ��� and it does, admittedly, seem strange to be watching a play that focuses on Sorley in a Brooke-like, golden-youth manner, given his own firm rejection of the Brooke-like, golden-youth cult.

It's also perhaps worth considering Sorley's poetry in the context of the question William Boyd asked in the TLS earlier this year: "What exactly is Scottish war poetry, as opposed to war poetry in general? . . . it is surely not possible to ring-fence the artistic expression of a response to the various traumas and stresses of war by a national label." Yet there is Sorley, among others, in an nationally themed anthology, reviewed by Boyd, that presumes exactly that.

As directed by Max Key, perhaps the Finborough production's most impressive theatrical characteristic is its smooth dovetailing of song, dialogue and recitation, with the warm lighting by Rob Mills accentuating this small theatre's cosiness. (It's a space McPherson knows how to write for, incidentally, since he is the Finborough's artistic director.) The tenor Hugh Benson and pianist Elizabeth Rossiter provide a splendid recital's worth of the appropriate numbers: George Butterworth's setting of A. E. Housman's "On the Idle Hill of Summer", a jolly "Gaudeamus Igitur" for Sorley's mixing with German students. Overall, the show makes an enjoyable, smaller-scale foil to Iain Bell's recently premiered operatic adaptation of David Jones's In Parenthesis.

It Is Easy To Be Dead does feel slightly too long for the story it has to tell, proceeding as it does in leaps and excerpts. The parents come and go, working through their son's papers; they struggle with grief and, in William's case, a desire to hang on to his son through his literary remains, and not to lose him to the world. Despite such anguishing scenes, however, the play seems to lack the final stroke that would reveal some message beyond the obvious one, about the First World War's futility and the bloody waste of young lives. That much the audience can bring along for themselves.

McPherson's homage did make me wonder, though, if Sorley's letters rather than his poems constitute the more rounded achievement ��� in that review, Corcoran thinks the letters "excellent", the early poems "an adolescent stew of Meredith and Masefield". Either way, you can see why William Sorley remained so keen to protect his son's literary legacy. After all, he could write to the TLS, in 1930, merely to complain of the meaning-mangling misprints in an anthology edited by Laurence Housman called War Letters of Fallen Englishmen.

There are, incidentally, TLS reviews in the pipeline of some of the latest round of centennial war books; and readers interested in the war and literature should know that Patrick Miles has resumed his excellent blog about a writer and former TLS reviewer killed in the war, George Calderon, whom I have mentioned here once or twice before. I'd like to think Calderon and Sorley, killed within months of one another, on different fronts, could have had a profitable conversation about literary matters, had they ever crossed paths.

Remembering Professor James Campbell

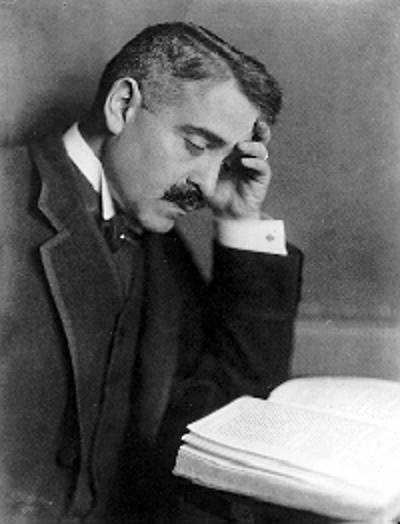

Professor James Campbell, 2009; a still from an interview conducted by Alan Macfarlane

By ALEX BURGHART

I have just returned from a funeral in St Mary���s, Cogges, Oxfordshire ��� a tranquil corner of old England where, to paraphrase Larkin, the place names are all hazed over with flowering grasses and, under wheat���s restless silence, the fields shadow Domesday lines. The bigwigs of medieval history gathered there to say their final goodbyes to Professor James Campbell, one of the finest minds ever to write about Anglo-Saxon history and, perhaps, the last of the old dons.

Many people are donnish. But there was nothing -ish about James���s donnery. He smoked a pipe until he was seventy. He liked a drink before, during and after tutorials (a "swift half" before Hall was not always swift and not always a half). He could be madly disorganized ��� one former student reported seeing his unmarked essay on James���s floor many years after he had graduated. He never learnt to drive and he never used a computer ��� after the typewriter he liked became obsolete all his essays were written by hand. He was intensely myopic and could use his jam-jar glasses to dramatic effect. He needed very little sleep ��� one friend who holidayed with him reported waking up in their Moscow hotel room in the small hours to find him reading the works of the soviet geochemist Vernadsky and puffing on cheap Russian tobacco. He was deeply loyal to his Oxford College, Worcester, which had made him a Fellow when he was twenty-two; he stayed there for forty-two years, never completing a doctorate and migrating straight from "Mr" to "Professor". He was a bachelor until his seventies, when he became a happily married man.

Most of all, he had a wholly remarkable storehouse mind which seemed to contain detailed notes of everything he had ever read ��� and he had read hungrily and omnivorously for a very long time. This reading fuelled a huge flotilla of interests ��� everything and anything from cannonballs to the herring trade to minor Irish country houses to German political thought and beyond. He once said, quite rightly, that "in terms of people teaching well and being useful to the University, people who read a lot are at least, or even more, important than people who write a lot". For his part, he adored teaching ��� he hated it when younger dons considered it a burden ��� and his students adored being taught by him. Many have talked about the experience for the rest of their lives.

In some ways he was a man from a different time. Raised by his grandparents in the rural East Anglia of the 1930s and 40s, he had a deep connection with previous generations and the England that they had inhabited. He had met his great-great uncle who had been born in 1848 and who was a successful bookmaker despite being illiterate ("the only man in my family ever to make any money and he left it, not to one barmaid, but two"), and he told stories about his grandmother's grandfather who had been a "witch-doctor for cattle" and had gone from herd to herd laying hands on sick cows with a tame bantam cock perched on his shoulder as a familiar.

It was perhaps inevitable that such a man, who seemed to know, almost at first quarters, something of the time before the industrial revolution, would develop a deep reverence for and empathy with England's most ancient institutions. A number of his essays profoundly illuminate the sophistication of the late Anglo-Saxon state ��� how orderly, centralized and uniform it was. But he also showed, as the great nineteenth-century constitutional historians had done, how the Anglo-Saxons' shire and hundred courts had required the participation and co-operation of ordinary people and how this participation had "maintained a kind of freedom, of non-absolutism, in the polity". Such readings make Anglo-Saxon history more than interesting; they make it important, because they involve the period in the history of liberty. Indeed, his work consistently showed that much of what is taken to be modernity in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was actually much older (what he often called "very old indeed").

James did not shy away from the consideration of great antiquity. He noted that Domesday Book used much the same system of land assessment that had been in place 400 years earlier when the written record began. He argued that this might simply be the first glimpse of already ancient systems that had allowed for the construction of Maiden Castle hillfort in the first millennium BC and that of Stonehenge in the third. But because he could see equally antique parallels in the organization of Neolithic Ireland and early medieval Denmark, he could detect the possibility of an "Indo-European grammar of government common to the local administration of much of Europe over very long periods, but coming to light and knowledge only late".

Every time I talked with James, I always learnt something that I would not otherwise have known. It meant that I had conversations with him that I could not have with anyone else. And now those conversations cannot be had. In his Festschrift, his friend and former pupil, the late distinguished Anglo-Saxon scholar Patrick Wormald, wrote that "James Campbell���s importance lies not in the vast amount that he knows, nor even in the unexampled richness of what he writes, but in how he has taught historians of early times to think". That importance lives on.

June 20, 2016

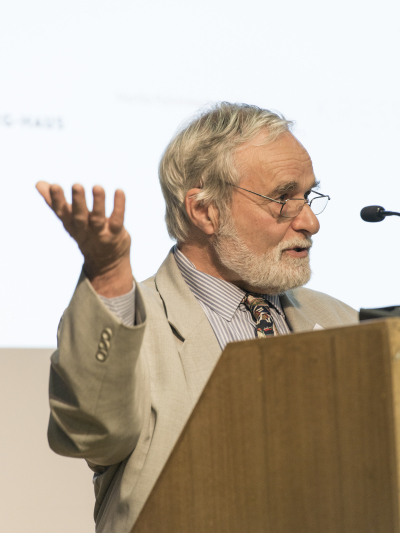

Stick and stickability

By MICHAEL CAINES (no pun intended ��� ed.)

There is a modest tradition of walking sticks propped in literary corners ��� in the writings of Leigh Hunt, Richard Steele and a few others. Steele didn't always trust them: "a cane is part of the dress of a prig", he suspected. Wounded soldiers aside, there were too many "peaceable cripples" who, "in this warlike age", "think a cane the next honour to a wooden leg". Hunt was more defensive of the innocent instrument itself. He felt the insult was misplaced when people were called names such as "a poor stick, a mere stick, a stick of a fellow". "We protest against this injustice done to those genteel, jaunty, useful, and once flourishing sons of a good old stock."

There is a self-flattering Edmund Gosse anecdote about Tennyson, as published in the TLS in 1904, in which the younger man seeks to impress the Poet Laureate with a fine line about ��� what else? ��� Rosicrucianism, likening the mysteries of that secret society to the mysteries of the art of poetry. The poet's response was gratifying: "He paused to listen, and then beat his walking-stick upon the gravel with fervent approval". Walking sticks, it seems, are not merely an aid to perambulation . . . .

For Dickens, whose own sticks survive in various museums, sticks could have personalities of their own. Jenny's crutch-stick in Our Mutual Friend, at one point, "seemed to entreat for its owner to come in and rest by the fire". In the same novel, Boffin's "seemed to be whispering in his ear". Around the same time, Punch patronisingly advised the frugal young lady who wished to adopt a cane for fashion's sake to "convert her last year's parasol stick into a new walking one, and so save Papa the cost". Although equally chappish, Hunt reckoned the stick to be an ancient and universally useful invention. Hence its diversification in modern times, with three related categories of use: "to give a general consciousness of power"; "to help the demeanour"; and "to assist a man over the gaps of speech ��� the little awkward intervals, called want of ideas".

The eighteenth-century stick could be a means of attack or defence ��� the ursine Dr Johnson's stick was meant to be a considerable deterrent ��� but Hunt had in mind the usefulness of a stick to "any one who has known what it is to want words, or to slice off the head of a thistle". "How his foot keeps time to the switches! How the passengers think he is going to ride, when he is or not! How he twigs the luckless pieces of lilac or other shrubs, that peep out of a garden railing! And if a sneaking-looking dog is coming by, how he longs to exercise his despotism and his moral sense at once, by giving him an invigorating twinge!"

Sticks need not be so energetic. In more recent times, when the Australian writer Donald Horne had to stop for a rest in the street, he switched from walking-stick mode ("using it as a rudder on the flat and as alpenstock on slopes . . . not to mention the swinging of the tip with every second or third step to show who is in control") to "shooting-stick mode". He would pause to take in the scene, "imagining a painting", only for strangers to ask if he knew where he was, and if he needed help getting back to his nursing home. Unfortunately, "to the uninformed eye, I can seem an old man lost". There is more telling meditation on age and its supports in Antony Thwaite's poem "In the Vicinity of the Crank-house".

This is a reminder of Coleridge's story about the "strange walking-stick, five feet in length" he bought from a countryman in in Cambridge, in 1794. This stick, he could claim, "a most faithful servant it has proved to me"; "sudden affection" swiftly "mellowed into settled friendship". When it went missing from the inn where he was staying in the Welsh town of Abergele, during a tour with a college friend, and an alarmed search revealed nothing, he resorted to giving the following lines to the town crier:

"Missing from the Bee Inn, Abergeley [sic], a curious walking-stick: on one side it displays the head of an eagle, the eyes of which represent rising suns, and the ears Turkish crescents; on the other side is the portrait of the owner in woodwork. Beneath the head of the eagle is a Welch wig, and around the neck of the stick is a Queen Elizabeth's ruff in tin. All down, it waves the line of beauty in very ugly carving. If any gentleman (or lady) has fallen in love with the above-described stick, and secretly carried off the same, he (or she) is hereby earnestly admonished to conquer a passion, the continuance of which must prove fatal to his (or her) honesty; and if the said stick has slipped into such gentleman's (or lady's) hand through inadvertence, he (or she) is required to rectify the mistake with all convenient speed. GOD SAVE THE KING."

This is where a Horne-like figure comes into view. Coleridge continues:

"Abergeley is a fashionable Welch watering-place, and so singular a proclamation excited no small crowd on the beach, among the rest a lame old gentleman, in whose hands was descried my dear stick. The old gentleman, who lodged at our inn, felt great confusion, and walked homewards, the solemn cryer before him, and a various cavalcade behind him. I kept the muscles of my face in tolerable subjection. He made his lameness an apology for borrowing my stick, supposed he should have returned before I had wanted it, &c . . . ."

For Coleridge, it was a fine bonus that a "very handsome young lady" in a coach asked for the copy of the bill Coleridge had given to the crier. "I acceded to the request with a compliment, that lighted up a blush on her cheek, and a smile on her lip."

By contrast: the saddest of literary sticks must be Virginia Woolf's. It accompanied her on her last walk to the River Ouse in 1941. Leonard found it on the bank, and it has now made its way to the New York Public Library.

My only excuse for taking this idle thought for a walk ��� swiping at shrubs, but no dogs, as I go ��� is an auction. You can view now (and buy tomorrow, should you wish and have a few hundred or thousand quid going spare) items from the collection of Roy Moore, a late "rabologist" (collector of walking sticks).

Over the surprisingly short span of two years, according to Chiswick Auctions, Moore acquired over 400 walking sticks from Europe and the US, many of them exquisite, rare and unusual. The Starck Barnes & sons walking stick pictured below, for example, is topped with a Royal Navy roundel and doubles as a flute:

This bamboo cane, meanwhile, of Chinese manufacture, doubles as an opium pipe:

That makes it not dissimilar in doubleness from this cheaper "folk art smokers companion" equipped with a clay pipe:

Whereas this reptilian curiosity in rosewood is perhaps only spring-loaded in order to impress, or terrify, the grandchildren:

I'd like to think that Leigh Hunt, the connoisseur of the "rhabdosophy, sceptrosophy, or wisdom of the stick", would have enjoyed all this ��� even if the porcelain handles weren't exactly what he meant about a stick's ability to "help the demeanour".

June 19, 2016

The taste of a painting

By REBECCA SWIRSKY

Can one taste an artwork? This was the synaesthesia-based conundrum I pondered while dining at a pop-up restaurant at Sotheby���s in New Bond Street. Chef Ollie Dabbous, dubbed by the food critic Jay Rayner "the most wanted chef in Britain", served six courses to coincide with the launch of the auction���s house Modern & Post-War British Art Sale (June 13 and 14).

Dabbous, whose restaurant (also called Dabbous) has received a Michelin star, said he was "drawn to the colours and textures, particularly with the more shape-driven abstract artworks that diners will be surrounded by���. As the pouring of wine commenced and paper bags containing warm bread were handed to tables, my fellow immaculately dressed diners were upstaged by even better-dressed walls: there were pieces by Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Elisabeth Frink, Lucian Freud, L. S. Lowry and Frank Auerbach.

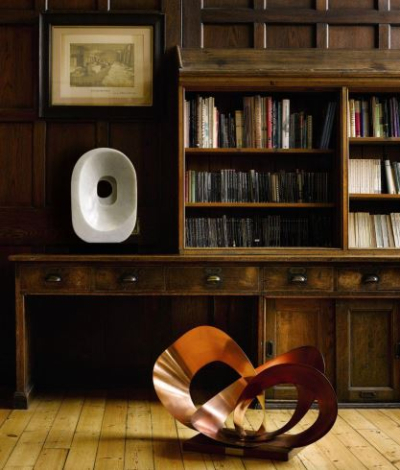

"Forms in Movement (Gaillard)" (1956), above, and "Quiet Form" (1973), below, by Barbara Hepworth

Dabbous���s inspiration was most evident in his third course, entitled "A Homage to Hepworth". A slice of bronzed kohlrabi sat atop a tasty offering of braised salt marsh lamb and wild garlic pickle; the dish bore a close resemblance to Hepworth���s "Forms in Movement (Gaillard)" (1956), one of the most valuable Hepworth lots in the two-day sale. Another lot, a white Seravezza marble sculpture entitled "Quiet Form" (1973), was a gift from the artist to her old headmistress, Miss Margaret Knott, on her retirement; Knott later re-gifted it to Hepworth���s alma mater, Wakefield Girls' High. Both sculptures were being sold in an effort to release funds for bursaries for future generations. "Forms in Movement", a structure consisting of three copper swirls, represents one of Hepworth���s earliest forays into sheet metal, and was acquired to celebrate the opening of the school���s gymnasium in 1960. The work was sold by Hepworth for the price of 200 guineas, half its market value at the time. Pupils were reportedly thrilled at its presence, with one poetically commenting that, ���it gleams like the setting sun, radiating a warm glow, and yet it has such a delicate hue���. Since Hepworth herself enjoyed two scholarships, first at the Leeds College of Art, then the Royal College of Art, the sale of both works to release bursary funds represents an agreeable circularity. ���I shall never forget the joy of going to school and the gorgeous smell of the paint I was allowed to use, nor the inspiration and help the Headmistress, Miss McCroben, gave me���, wrote Hepworth in A Pictorial Autobiography (1970).

���Ollie got a bit carried away by the naming���, acknowledged Graham Burton, general manager at Dabbous. He was referring to a green concoction of raw peas and iced mint tea, arriving with the title "England���s Green and Pleasant Land". The dish���s construction bore a natural resemblance to Patrick Heron���s ludic painting of Sydney���s botanical garden, "Sydney Garden Painting" (see pictures below), included in the auction. Heron, whose bright canvases are limned with dynamic unfurlings of colour, once said of his Antipodean experience: "I had a wonderful time [in Australia] in 1989���90 . . . . It wasn���t so much the landscape as the vegetation that got into the work". Biting into the vegetable crunch of Dabbous���s joyous pea-and-tea creation felt close enough to tasting a painting.

"Sydney Garden Painting",1990, by Patrick Heron

June 17, 2016

Baby talk

Considering that Louise Brown, the first "test tube baby", is thirty-seven years old, that one in six couples struggle to conceive, and that IVF, the "miracle" that produced Louise and so many others, is available on the NHS, it is surprising that the cultural impact of infertility has been so negligible, particularly in the theatre. We have had plays about everything from the privatization of the railways to the agonies of snooker, so the first sensation on seeing Gareth Farr's moving The Quiet House at the Park Theatre in North London (which runs until July 9) is that it is long overdue. Jess and Dylan are a happy, settled, professional couple in a sleekly decorated flat with an emptiness at its heart. They want a child, and can't have one. The decision to try IVF is not even discussed ��� it is just the logical progression from the medical evidence that without it, they haven't got a chance.

Without ever feeling schematic or preachy, the play takes up themes thrown up by their decision that might seem "obvious", were it not for the fact that no one ever seems to talk about them in polite society (by which I mean all society outside specifically designated support and discussion groups): envy or awkwardness arising from the ease with which others ��� in this case a neighbour in the upstairs flat ��� can conceive, and the daily reminder of that in the shape of a baby; the taboo around discussing either infertility or the decision to use IVF to address it; wounded male pride ��� about "being a jaffa" ��� and its mirror image, self-inflicted female shame ��� "it's always the woman's fault". When it comes to conception, we witness the substitution of a round of painful injections and medical procedures for the intimacy of sex, and how the couple compensate for that. Then there is the question of how a parent begins to relate to an unborn child, from the moment it first becomes a possibility, and the alternation of extravagant hope and overwhelming despair as the news of embryos, implantation and "viability" comes through.

Farr's achievement is to make Jess and Dylan experience all this as part of a genuine domestic drama, not a public information workshop. From the start, Dylan in particular is a compelling mixture of tortured modern partner, desperate to be supportive, and classic silent male, absolutely incapable of telling his boss why he needs time off, or even of using the company's own privacy policy to avoid doing so. For her part, Jess is both clear-eyed and practical, and racked with anxiety. The quietness of the title is not just the lack of of a baby's cries, but the silence of all concerned about what they are struggling with. Of course, as Jess points out, "everybody knows" that a couple in their mid-thirties who have been together for as long as they have, and haven't declared a decision not to have children, must be considering IVF, but no one feels able to raise it ��� even after the upstairs neighbour takes delivery of the enormous package from the Assisted Conception Unit when Jess doesn't answer the bell. Farr shows the enormous strain all this silence puts on those who experience it. The actors who play Jess and Dylan, Michelle Bonnard and Oliver Lansley brilliantly draw out our sympathy and sense of helplessness when confronted by their narrowing odds of success. If you haven't been through IVF, the chances are you know someone who has, but The Quiet House succeeds because it shows that these are people whose yearnings and contradictions strike a chord whatever your experiences are. It was worth the wait.

June 15, 2016

Re-Joyce-ing on Bloomsday

By MICHAEL CAINES

"Miss Dunne clicked on the keyboard:

��� 16 June 1904."

On June 10, 1904, James Joyce stopped Nora Barnacle in a Dublin street. "I mistook him", she later recalled, "for a Swedish sailor." She didn't show up to meet him, however, as arranged, a few days later, on June 14. If she had, that would be the date we now know as Bloomsday, as June 16 is now called, for its association with a meandering span of Leopold Bloom and the other Dublin characters in Joyce's Ulysses ��� for that is when they did meet again, and their passionate, complex relationship began in earnest. . . .

Fifty years later, as the date on which Joyce set the action of Ulysses, June 14 was to be chosen by John Ryan, Patrick Kavanagh et al as the moment for the inaugural Bloomsday celebrations in Dublin ��� at a point when Joyce was, as David Wheatley has pointed out in the TLS, "neither popular nor profitable in the land of his birth". (This is not to count the similarly convivial but less . . . posthumous affair of 1924, which Joyce was aware of.) Bloomsday is now marked, and not only in Dublin, by readings, drinkings and dressings-up, but back then a Dublin publican could assume that the revellers entering his establishment belonged to a funeral party: "Ah! the sign writer, little Jimmy Joyce from Newtown Park Avenue".

At least that's the all-too-Irish story ��� it's like an anecdote out of Flann O'Brien, who was one of those inaugural revellers. Many a fine story is probably to be told of Bloomsday and what it elicits from modern Dubliners. "James Joyce, is it?" The bookseller and TLS columnist Eric Korn once had this from a taxi driver as he arrived in town for Bloomsday in Joyce's centennial year. "That gobshite they threw out of the country for his dirty writings?"

The first mention of Bloomsday in the TLS that I can find in the archives is in a passing reference by the novelist Rayner Heppenstall, in 1957, to this "valuable adjunct to Eire's tourist industry", "with trips round Dublin . . . stopping at spirit stores to look at the characters". Four years later, the opening of the Martello Tower as a "shrine to the memory of James Joyce" apparently marked a new stage in appreciation, receiving considerable attention in the American press. The years have seen the tipsy ritual reach a municipally demanding scale. That centennial Bloomsday enjoyed by Eric Korn, for example, also witnessed a re-enactment of the "Wandering Rocks" chapter, "including 150 participants and a viceregal coach".

At Sandycove, meanwhile, Korn observed a "various and chilly crowd of devotees", "shaving on the gunrest, absurdly with electric razors, or toasting the day in Buck's Fizz in honour of plump Buck Mulligan". There were brave swimmers at it, too. "If I had a scrotum", one water-borne woman proclaimed, "it would surely have tightened." Another Kornish tale has Davy Byrne's Moral pub being advised to advertise a Bloomsweek special, in the form of burgundy and gorgonzola ("A cheese sandwich, then. Gorgonzola, have you?") for ��2. The advice is heeded. The sign reads: "BLOOMSDAY SPECIAL: GORGONZOLA AND BOURGANDY".

The TLS was nonchalantly late to review Ulysses itself. It had covered Dubliners ("The author . . . is not concerned with all Dubliners, but almost exclusively with those of them who would be submerged if the tide of material difficulties were to rise a little higher"), A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man ("It is wild youth, as wild as Hamlet's, and full of wild music") and Exiles (notably reviewed by T. Sturge Moore, who had campaigned without success for the Stage Society to overcome its scruples and produce the play). It continued reviewing Joyce after that, but ignored Ulysses ��� bar the odd nod ��� until 1937, by which time there was finally an English edition to review. The novel was, by then, thoroughly notorious: "there is an appendix", noted the reviewer, "giving, among other details of controversy, the decisions of the United States District Court and of the United States Court of Appeals which allowed Ulysses to be published in that country".

(An air of scandal weirdly clung to Joyce even as his work approached the expiration of copyright. Christopher Hitchens could note in the TLS in 1987 that a New York radio station risked the wrath of the Federal Communications Commission by announcing its annual reading of Ulysses on air. "The FCC was asked to state which passages might be risky, and loftily replied that that would be telling.")

Perhaps the most significant of those early engagements with Joyce's great work came in a review by Anthony Powell of a selection called The Essential James Joyce, in 1948, seven years after Joyce's death. While marvelling at Joyce's "mastery of his medium", Powell saw in Ulysses's gleeful pastiches the evidence of a "professorial attitude towards writing and [a] temperamental unwillingness to deal with the world of action in straightforward terms". And make what you will of both authors in Powell's concluding remarks:

"By mighty effort of will ��� will rather than imagination ��� [Joyce] produced a work that carried a certain sort of writing to its logical conclusions; and if there were nothing else to be said for Ulysses it might be defended on the plea that, once given to the public, such a book need never be written again. It is a literary oddity by a gifted writer, and it is hard to see how it can ever, or could ever, be otherwise regarded. However, Tristram Shandy is also a literary oddity and it has lasted close on a couple of hundred years to date. For Finnegans Wake we feel inclined to offer no such hope."

Perhaps Bloomsday in its modern guise may be thought of as a "normalizing" response to this oddity. It has served as convenient date for both the doling-out of literary prizes and coat-tail-grabbing publications such as Picador's dubious "Reader's Edition" of 1997: "the handy, usable Ulysses that we have been waiting for . . . smuggled out of the ivory tower of the academics and put squarely into the market-place". And in 2000 Julian Rathbone could reject the pedantic notion that one needed to read the book to be able to celebrate it. Dubliners, he reckoned, could feel something beyond pride and love for this writer: "Even if they haven't read a word, they know there was a man, there is a book, that understands and knows them in all their wonderful, terrible, terrifying, pitiable and admirable loneliness and companionship". I admit that I take his point.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers