Peter Stothard's Blog, page 8

May 16, 2016

Craig Brown���s A-Z of Humour

By SAMUEL GRAYDON

The Olivier Award-nominated actress, singer and comedian Dillie Keane took to the stage, to much applause, and began a set of ���songs about [her] personal life��� ��� ���personal��� meaning very personal indeed. ���Those aren���t my handcuffs��� and ���I swear I���ve never seen those girls before / Nor that horse!��� were some of the cleaner lines. Twenty minutes into the set, in her ���Song for Sexual Re-Orientation���, Keane weighed the pros and cons of lesbianism.

I began to wonder if I was at the right event.

I had thought I was attending the satirist Craig Brown���s "A���Z of Humour��� as part of the London Library���s ���Words in the Square��� celebration, which marks the 175th anniversary of its foundation in St James���s Square. As it turned out, Brown, accompanied by the actress Eleanor Bron, and the impressionist Lewis Macleod, came on after an interval. Among its other aims, The London Library wants to encourage ���a delight in literature and the arts���, and it appeared that this meant that Keane and Brown needed no discernible overlap besides the fact that they were both funny. As with most literary festivals, comedy was merely an accessory, and not an independent contribution, to the conversations and debates about literature. Brown���s half of the evening was effectively a collection of his best parodies, organized under very loose categories (presented alphabetically) such as "Juxtaposition", with occasional hints at their use in comedy.

Brown knew his audience ��� M was for Malapropism, V for Verbiage and L for Literary Festival, no less. But, as a result, the event did on occasion feel a little exclusionary: at one point, Brown said: ���I shan���t explain what a clerihew is, for we all know���. A woman sitting behind me spent a lot of her time explaining every other joke to her partner (who didn���t know what a clerihew was), which brought to my attention how much people were laughing at their own knowledge. But then, inclusion and exclusion are part and parcel of comedy, and if one does have the rare opportunity to laugh at a joke about Edith Sitwell, Beatrice Webb, or W. B. Yeats, one may as well revel in it. I laughed as hard as anyone when, in what Brown called ���Harold Pinter���s Revised Book of English Verse���, the audience were treated to:

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made;

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee,

Until the Yanks come and fuck the shit out of it.

More recent figures were ridiculed as well, however. Barack Obama, Tony Blair and John Prescott (imagined as having to pose for a portrait by Lucian Freud) all came under fire. But best of all was "D was for Donald" (a parody of Donald Trump���s Twitter account). Despite the occasional exaggeration of character, it was probably the closest to real life of any of the sketches, not least because of Macleod's spot-on performance. At that point everyone was laughing at Trump, rather than at an imitation of Trump ��� it was the only point in the night when there was any discomfort in the audience, as there should be in the best satire.

But then, I thought, this was perhaps not the point. Free prosecco, a marquee, sunshine and beautiful arrays of tulips are not conducive to Juvenalian satire ��� far better to laugh at sex and swearing and authors.

May 13, 2016

Views of Casanova

From The Fable of Casanova (1934)

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

There���s a wonderful review by David Coward in this week���s TLS of a new French edition of Giacomo Casanova���s Histoire de ma vie. Coward gives us as rounded a portrait of the Venetian adventurer as we could hope for in 2,500 words.

As Coward reminds us, the book runs to well over a million words and was written in Italianate French, French being the lingua franca of eighteenth-century Europe. There is an English translation in print entitled History of My Life, single-handedly completed by the heroic American scholar Willard R. Trask. It first appeared in six substantial annotated volumes in the 1960s, and seems unlikely to be superseded.

History of My Life is generally reckoned to be one of the great eighteenth-century autobiographies, ranked alongside Rousseau���s Confessions. The great American critic Edmund Wilson called it the ���most interesting memoirs ever written���.

One of Casanova���s most fervent advocates is the French novelist and critic Philippe Sollers, who is not beyond speculating on occasion: ���it���s easy to imagine that he met Mozart���. He describes his hero as ���a handsome man with a very dark complexion���, and points out that he was 1 metre 87 in height (he couldn���t stand up properly in his prison cell in Venice). Sollers���s Casanova l���admirable was published in 1998 (the 200th anniversary of Casanova���s death), and has now appeared in English as Casanova the Irresistible (translated by Armine Kotin Mortimer; 154pp; University of Illinois Press). The review copy came into the TLS offices too late to be included in Coward���s review, although the French edition was favourably reviewed in 1998 by the late Robin Buss.

Sollers���s book takes the form of an erudite meditation on Casanova���s life and his potent afterlife. It is not without humour: while in prison, Casanova is prey to ���the fleas, the permanent sweating, hemorrhoids, fever, and, on top of that, debilitating mystical readings ��� why not, while they���re at it, a collection of sermons by the Dalai Lama?��� Elsewhere he writes, ���if Casanova were put in prison today, the black humor would be to want to re-educate him by making him study the complete works of Pierre Bourdieu in depth, for example��� (Sollers has had his battles with fellow Parisian intellectuals over the decades, including the sociologist and anthropologist Bourdieu).

The author has fun at the expense of Casanova���s first editor, the Frenchman Jean Laforgue who, not content with correcting Casanova���s French, removed passages he disapproved of. For Sollers ,���Laforgue is a specialist of the fig leaf (each period has such ���restorers���)���. ���Women perspiring, odors, food, political opinions: it all needs to be kept under surveillance. If Casanova writes ���the low people of Paris���, he���ll be made to say ���the good people������. Sollers adds, ���A woman, according to the professor, cannot be represented lying on her back while ���masturbating���. No, she will be ���in the act of deluding herself��� (understand it if you can)���.

An interesting aspect of reading a translation of a book published seventeen years ago is observing how the world has moved on in the intervening period. For example, Sollers is scornful of a fast- food restaurant in Prague called Casanova ��� an abomination, in his eyes. He imagines a book entitled The Cooking of Casanova. He is becoming ���a brand name���. Well, yes, all this has happened, and more.

May 12, 2016

There once was a writer called Lear . . .

May 12 is the anniversary of the birth of Edward Lear. So it's also, inevitably, National Limerick Day. Cue much excited circulating of the innocent and NSFW varieties of the form. . . .

As was pointed out in the TLS in 1924, in what I think is the paper's earliest review of an anthology of limericks, the essential ingredients of a good limerick are "a good last line, ingenuity of rhymes, and plot". And light as they are, they're a fair introduction to some of the elements of verse (if not Poetry with a hifalutin capital P). Even then, Arnold Bennett could tell the editor of that limerick anthology that "the best ones are entirely unprintable". That tendency is perhaps best exemplified by Isaac Asimov's Lecherous Limericks, Norman Douglas's often pirated collection Some Limericks and the fact that there's a Playboy's Book of Limericks of 1972. (Why no accompanying volume on heroic verse or the villanelle?) Let "On the bridge that spanned a ravine / Archibald was screwing Kathleen . . ." stand for all of that.

Still, it seems that anyone can write one and everyone does. There are plenty of game attempts amid this morning's 5,000-odd #NationalLimerickDay tweets, some weak, others amusing ��� off-the-cuff, either way, is often best. Many become popular that originated with that well-known and versatile author Anonymous. Philip Larkin found himself in a Westmorland village called Kaber and sent off this limerick to Charles Monteith, his editor at a certain London publisher:

There was an old fellow of Kaber,

Who published a volume with Faber:

When they said: "Join the club?"

He ran off to the pub ���

But Charles called, "You must love your neighbour".

As Monteith recalled in the TLS in 1982, the third and fourth lines were fillers that could be replaced at a later date as occasion demanded. For example:

When they said "Meet Ted Hughes",

He replied, "I refuse" . . . .

Lear's limericks were about Old Men from Tobago or Hong Kong, and young ladies from Parma or Portugal. They are not all, however, simply jokes. There's a strange preponderance of people stuck on walls or pillars ��� "fraught with Freudian possibilities", Claude Rawson has observed. And there's the old man whose despair "Induced him to purchase a hare"; the outcome is not wholly comic:

Whereupon one fine day,

He rode wholly away,

Which partly assuaged his despair.

(Also, a fine point, but am I messing up Lear's preferred four-line arrangement of the limerick?)

Others have found ways to make the limerick topical, xenophobic, or topical. Clement Attlee managed an autobiographical one. The prolific Robert Conquest "has a first-rate limerick on Lenin", a TLS review once noted, although it should perhaps have pointed out that he was also a master of the bawdier variety. (Conquest gives a good example of the properly Byronic impudent rhyme in his one about Arnold Toynbee, incidentally: "So how would a kick in the groin be?") Here's another, of a later date, about Einstein's theory of relativity:

There was a young lady named Bright

Whose speed was faster than light;

She went out one day

In a relative way,

And returned the previous night.

As Anthony Burgess once pointed out in the TLS, however, the limerick boasts a grand history that stretches back beyond Lear to claim Ben Jonson as an ancestor (these lines appear in a masque of 1621 called The Gypsies Metamorphosed):

The wheel of fortune guide you,

The boy with bow beside you;

Run aye in the way

Till the bird of day

And the luckier lot betide you.

There's an even older instance in medieval Latin, beginning "Si vitiorum meorum evacuatio . . .", and apparently there are even Saxon prototypes. So this sort of nonsense has been going on for some time.

Burgess was writing in 1978. Conquest himself had noted in the TLS nine years earlier, of a book called The Lure of the Limerick that "It marks, one supposes, some kind of epoch when a respectable London publisher gives us a collection of limericks, including many of the most obscene, in the form of a sort of small coffee-table book". Indeed. Conquest could certainly, by then, quote a naughty one in the paper about "Victorian attitudes":

Charlotte Bront�� said, "Wow, sister! What a man!

He laid me face down on the ottoman

Now don't you and Emily

Go telling the femily

But he smacked me upon my bare bottom, Ann!"

I'm sure you've heard ruder. The bumpy rhythm of this one reminds me, though, of W. S. Gilbert's cunning breaking of the rules of rhyme:

There was a young man of East Cheam

Who one day was stung by a wasp.

When asked: Does it hurt?

He said: No, it doesn't,

But I'm so glad it wasn't a hornet.

One more note about Conquest. That review of his inspired a two-stanza reply from the publisher of The Lure of the Limerick:

The savants who write for The Times

Never overlook publishers' crimes:

"The original metre

Was very much neater,

The author's were far better rhymes."

"Now the author", they're sure to go on,

Was my grandfather, Bishop Anon,

And the earliest version

(Derived from the Persian)

Was privately printed in Bonn."

On that note . . . It's not always possible to approve whole-heartedly of contrived National [insert worthy theme here] Days. But I asked around TLS HQ all the same, in case anybody was in the rhyming mood. And here's what happened ��� rendered, as is only right, Anonymous. I apologize in advance for getting into the spirit of things, and will revert, at the next blogging opportunity, to normal cynical service. (Further examples welcome, obviously.)

There was once a debate about Brexit.

Full of info (but nobody checks it).

It all ends in shouting,

Grumbling and pouting.

Any reasoned debate: someone wrecks it.

There once was a website called Twitter

That Franzen thought equal to litter.

"It's great!", someone said --

"You're wrong in the head!"

It ended up really quite bitter.

There once was a golfer named Clough

Who away from the links was quite gruff;

But the use of his putter

Got his caddy a-flutter

So they did it right there in the rough.

The sky over London is chalky

But the skyline���s appallingly gawky:

It is ravaged and scarred

By, e.g., the Shard,

The Gherkin, the foul Walkie-Talkie.

There once was a literary hack

Who was asked to reveal the knack

For writing a limerick ���

���And make that double quick��� ���

Despite his marked lyrical lack.

There once was an icebox replete

With plums so deliciously sweet

That I gobbled the lot

And completely forgot ���

Was this the breakfast you were planning to eat?

A chap not averse to a tweet

Got a job at a literary sheet ���

So excited was he

That he jumped up with glee ���

And tore a great hole in his seat!

And lastly, as recommended by the poetry editor, here's a polite one by Robert Conquest:

Seven Ages: first puking and mewling

Then very pissed-off with your schooling

Then fucks, and then fights

Next judging chaps' rights

Then sitting in slippers: then drooling.

May 11, 2016

The cr��me de la cr��me

By THEA LENARDUZZI

Every ten seconds, a TLS writer is nominated for an award somewhere in the world. Well, perhaps not quite, but the statistic can���t be that far off, and to keep track of all of our writers��� achievements would require a whole new department in JC���s basement labyrinth. (Its employees would have to be kept apart from those working on the committee of the All Must Have Prizes Prize, mingling only in the windowless canteen where they might exchange a respectful nod across their lukewarm bowls of gruel.)

Food may not be the first thing that people think of when they think of the TLS, but it will come as no surprise to many that our long-time contributor Bee Wilson should be shortlisted for a Fortnum and Mason award for her writing in the TLS. (Her pieces for the TLS include reviews of The Health Gap: The challenge of an unequal world by Michael Marmot and four books on the history of food, including Eatymologies by William Sayers and A Century of British Cooking by Marguerite Patten.) Wilson joins Tim Hayward and Xanthe Clay in competing for the annual Food Writer toque, and there are fourteen other categories, including Restaurant Writer (Giles Coren; Marina O���Loughlin;���Tracey MacLeod), Cookery Writer (Felicity Cloake; Itamar Srulovich and Sarit Packer; Rachel Roddy), and Radio & Podcast (Farming Today; On Your Farm; The Food Programme). Winners in each category will receive, among other things, a ���luxury hamper worth ��500��� (at which point one hopes they'll remember their greying, gruel-bloated editors . . .).The cr��me de la cr��me will be announced tomorrow ��� best of luck to all.

May 6, 2016

Utopian voting

It's futile, many a Middle England type would say, to vote for Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party. What's the point in voting for this supposedly unelectable figure? Look at the local election results coming in from around Britain today: Labour defeated in Scotland; and merely, as far as anyone can tell at the moment, holding steady across England when they ought to be making dramatic gains in the face of Tory venality, hypocrisy, in-fighting etc, as previous opposition parties have done. It seems that my old MP Sadiq Khan has won the London mayoral election ��� but that's despite Corbyn, some have said already and no doubt will go on saying.

As a wise head told me this morning, however, some see an urgent point in trying to correct the right-wards drift to which the Labour Party has succumbed over the past two decades. Leaving aside the apparently unlikely scenario of a Labour victory in the General Election of 2020, even if Corbyn is out well before then, whoever succeeds him would have to acknowledge and accommodate the majority of party members who have supported him, rather than sinking back into the purest Blairism. It's that, some say, or a permanent split.

There is a dirty word that Right-thinking people occasionally like to throw at such idealists: utopian. The word in this context means: unworldly dreamer, one whose notions would be catastrophic if ever put into practice. It's the word Marx and Engels used to dismiss early socialist thinkers such as Charles Fourier and Robert Owen. And it's time the word was reclaimed, I think. 2016 is, after all, the year in which Thomas More's mighty book Utopia turns 500. It's about time we learned again what that mischievous coinage could possibly mean . . . .

Commentators have already tried to link Utopia to the Labour leader, sometimes with spectacular ineptitude; for one thing, Utopia does not advocate a "broad-minded attitude to religion". Nor is it simply a book about having an "extremely authoritarian state". (There is ignorance of another kind on display in one commentator's recent suggestion that the pun encoded in the word "Utopia", meaning both the good society (eutopia) and no place (outopia), is More's "only recorded joke". He made at least one more.)

On the other hand, nobody could know everything there is know about this subject. There is a library's worth of commentary on Utopia itself, as well as countless literary imitations and a long history of sometimes disastrous attempts to put "utopian" ideas into practice. There is a Society for Utopian Studies and its long-running publication Utopian Studies. This year's 500th anniversary, marking five centuries of Utopia and utopianism, brings us all manner of events around central London; and, to satisfy the academically minded inheritors of the humanist tradition in which More himself worked, there are conferences taking place in Leuven (the city where Utopia was first published), Lisbon and St Petersburg, FL. (The conference in Antwerp, where More sets the first half of his book, has been and gone.)

And ��� ahem ��� everyone is welcome to "Utopia: Then and now", a discussion I'm chairing at King's Place in London on May 16, with some excellent, "utopologically" minded speakers; it would be just grand to see some TLS blog readers there. (Whet your appetite with this recent episode of TLS Voices, which concentrates on Utopia "then" and what More wrote . . .)

(All right. Plug over.)

So what is a utopia?

The simplest answer is that it is an imaginary or real state or community designed to improve everyone's lot. Hence the belated rise of its opposite: the dystopia, a term only coined after the Industrial Revolution, in which everyone except the lucky few is worse off.

There are further distinctions to be made, though, between Land of Cockayne fantasies of plenty without end and elaborate, serious-minded attempts to devise, at least in outline, a world and the way it would work. Another useful distinction, delineated by Elisabeth Hansot in Perfection and Progress (1974), separates "classical" utopias from "modern" ones: the first, in her view, are contemplative and static, like Plato's Republic; the second type are about the possibility of real change.

Partly as it's often described as a satire, I guess More's Utopia could easily be categorized as the first of Hansot's two types. It mocks the disorderly England of the sixteenth century; the island commonwealth of the title, on the antithetical side of the globe, is everything More's world wasn't. Private property doesn't exist there, the citizens are wonderfully reasonable and all social problems have evaporated. (The few bad apples are serenely made better, or dispatched.) The learned traveller in whose mouth More puts his description of Utopia, Raphael Hythloday, entirely approves of everything he sees there.

An alternative view of Utopia is offered by the excellent Open Utopia edition:

Hythloday finds himself at the table of a political figure drawn from life, Archbishop John Morton, and, in this elevated company, stridently condemns contemporary abuses of power in England, such as the ruthless enclosure of common land and the imposition of the death penalty for petty crimes. These criticisms crash, however, against the firm defences of ignorance and bigotry; Morton himself is receptive, but his hangers-on convert his pronouncements into opportunities for mere sycophancy.

"Their received notions must prevent your making an impression on them", Hythloday is told. He is advised to follow a different course:

"If, when one of Plautus��� comedies is upon the stage, and a company of servants are acting their parts, you should come out in the garb of a philosopher, and repeat, out of Octavia, a discourse of Seneca���s to Nero, would it not be better for you to say nothing than by mixing things of such different natures to make an impertinent tragicomedy? . . . go through with the play that is acting the best you can, and do not confound it because another that is pleasanter comes into your thoughts."

To Hythloday, direct confrontation is the only approach worth taking. Unwittingly, though, he takes this other option, suiting his argument to its moment, with his description of Utopia. It is his Plautine comedy, an entertainment intended not to blast his interlocutors into submission but giving them to chance to contemplate the common problems of the world. It is not a rhetorical end in itself but the means to an end.

Just as Morton's dinner table gives us a mock-Socratic dialogue, Utopia can certainly be read as a satire ��� but that is not all it is. The name "Raphael Hythloday" would have warned More's readership of fellow humanist scholars that its owner was a "speaker of nonsense", yet the nonsense he speaks turns out to contain some surprisingly noble sentiments. The devout More is extremely unlikely to be mocking Jesus's teachings when he has the Utopians refer to their "community of goods" and explicitly acknowledge its Christian precedent.

If the book is not a blueprint, this reading suggests, it might instead be called a "prompt" ��� a nudge in the direction of thinking creatively yet realistically about shared political, social and philosophical problems. Through Hythloday, More offers a vision of a different way of life. Readers/travellers are meant to explore it and return to their own world enriched. Not morally purified in some extraordinary way, or subjected to a conversion to More's beliefs, but perhaps prepared to think differently. Who could make that journey, return home and lapse back complacently into their own imperfect modus vivendi?

So when people talk about the "utopian" schemes of a naive variety ��� well, I know what they mean. But to be truly "utopian", in the spirit of the great book itself? Now there's a compliment.

May 5, 2016

Alain Jupp��, president-in-waiting?

Alain Jupp�� delivers a speech, Saint-Gr��goire, western France, on April 20, 2016. Jean-Fran��ois Monier/AFP/Getty Images

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Alain Jupp�� is mayor of Bordeaux. He has an illustrious predecessor in that position: Michel de Montaigne, who reluctantly took up the post in 1581 and served until 1585. Those were troubled times: wars between Catholics and Protestants were raging in the region and, from June 1585, a plague in the city that took away some 14,000 souls in six months (Montaigne was criticized for not leaving his chateau to attend his successor���s investiture in the plague-ridden city).

Montaigne isn���t mentioned in the journalist Ga��l Tchakaloff���s new book about the eighteen months she spent in Jupp�����s entourage, Lapins et merveilles (265pp. Flammarion. ���19). The reason for her assignment? Jupp��, if the polls are to be believed, could become France���s next president this time next year. He is well ahead of his fierce rival Nicolas Sarkozy, and on the Left, no candidates have declared themselves yet. Jupp�� is seventy ��� which would make him a year older than Donald Trump and two years older than Hillary Clinton.

Bordeaux itself hardly appears in Tchakaloff���s narrative: there is a moment when a youth approaches Jupp�� in the street there and asks him if he is the mayor, to which he stiffly replies ���yes��� and walks away. Clearly, he doesn���t have the common touch. But being mayor of one of the country���s larger cities is undoubtedly a useful springboard for higher office. After all, Jupp�����s mentor Jacques Chirac served as mayor of Paris before his two terms as president (1995���2007). Sarkozy was, at the age of twenty-eight, mayor of the town of Neuilly-sur-Seine, while Fran��ois Hollande held the post in the even smaller town of Tulle in the Corr��ze region.

Tchakaloff���s book is a partly successful attempt at a psychological portrait (there���s no discussion of Jupp�����s political record ��� he served as prime minister during Chirac���s presidency ��� or his policies). ���I���m well aware that you have to be a little screwy to spend eighteen months with Alain Jupp�����, she writes early on. Indeed, she struggles to break through his thick carapace; to mix metaphors, she describes him to her editor as a ���block of ice���, hence the need for eighteen months rather than, say, five or six: ���Alain, closed, double-locked. Me, the opposite. Extrovert, expansive, excessive���. Politically, she���s on the left; he is centre-right.

Ga��l Tchakaloff, Paris, April 4, 2016 - Martin Bureau/AFP/Getty Images

He has something of the technocrat about him. In the 1980s, colleagues would refer to him as ���Amstrad��� in recognition of his data-processing abilities. But the politician who emerges from these pages is also likeable: he listens to the Goldberg Variations and reads Pl��iade volumes. He takes twenty-five family members on holiday to Greece to celebrate his seventieth birthday (he has been married twice and has three children). His politics are centre-right but he appeals to many on the left. (To my untrained eye, he appears statesmanlike too.)

As she watches the two men debate, Tchakaloff draws a comparison between Jupp�� and Sarkozy, who with his ���malleable neck, . . . protruding eyes, angry beak��� reminds her of a little screech owl, hopping from one leg to the other. Jupp�� is more like a peregrine falcon. ���Long-legged, he keeps his distance, draped in heavy wings, wheeling round from time to time to show off his height and administer his jabs.���

As Le Monde has pointed out, Jupp�� is unlikely to enter into any sort of pact with the Front National, or to try to reach out to its supporters, unlike Sarkozy. The leader of the Front Marine Le Pen recently wrote, with heavy irony, ���Who would have thought at the time of massive strikes against Alain Jupp�����s government in 1995 that, twenty-one years and several ministerial portfolios later, the same Jupp�� would try to embody renewal?��� It sounds as though he has her rattled.

By the end of her time with the entourage, Tchakaloff appears reluctant to leave. She has grown fond of her subject, even if she���s not sure what to make of him. I sounded out informed opinion about Jupp�����s chances next year ��� they were rated negligible: he���s too much of a technocrat and has too much baggage (not unlike Hillary Clinton, then!). But these are strange political times, so who knows?

May 4, 2016

The Jungle Book rebooted

By SAMUEL GRAYDON

Taken by a sense of childhood nostalgia as I passed the Picturehouse in Greenwich, I went recently to see Jon Favreau���s ���live-action��� remake of Walt Disney���s The Jungle Book.

I slightly regretted this unusual spontaneity as I sat through half an hour of children���s adverts surrounded by couples and families. But, as the lights dimmed and I donned my 3D glasses, it hardly mattered. Even as the Disney logo disappeared behind jungle foliage, I was gripped. Not because of the fast-paced action sequence that begins the film, or even because of Ben Kingsley���s distinguished narration as Bagheera, but, to my surprise, because of the CGI animation.

Even if the film had been disappointing in all other aspects, I still would have come away impressed. The landscape simply looked real. Fantastical, but real. Had I not known beforehand that it was shot almost entirely against a green screen, I would not have believed that it wasn���t shot on location. Favreau has referred to the graphic technicians on the film as artists, and it would seem foolish to call them anything else.

And for this reason ��� that the world of the film is completely artificial ��� the best performance of what is quite the all-star cast is given by Neel Sethi (aged eleven/twelve at the time of filming), who plays Mowgli. In fact, he seemed so natural in his surroundings that he managed to supply a depth lacking from 1967 incarnation of the man-cub.

Of all Disney���s modern ���live-action��� remakes of their cartoon classics, The Jungle Book seems the most indebted to its predecessor. The film paid obvious homage to the original film in many ways, and in the opening and credit sequence it was almost shot-for-shot. Favreau was not afraid of bringing forth some of the darker and animalistic elements of the story, however ��� a process helped, of course, by the ���photo-real��� wolves, tiger and bear. Indeed, the film seemed torn between Kipling���s Jungle Book and Disney���s, and so attempted to meld the two; I felt that this didn't always work.

I was unsure about the inclusion of the songs, for example ��� they came as a surprise, and initially seemed to jar with the more violent, more serious elements. A huge King Louie, voiced by Christopher Walken, erratically singing ���I Wanna Be Like You���, seemed a little off-kilter with the scarred and bloodied ten year-old who was his audience. (King Louie is so big because, wanting to represent native wildlife, Disney opted not for an orang-utan but for a species of ape, Gigantopithecus, that became extinct in what is now India between 100,000 and 9 million years ago.)

But then again, this is primarily a children���s film. More than that, this is Disney, a studio which ��� with its wizard-mouse and pink elephants ��� has always had a sense of the playful and the absurd. A giant, long-dead ape who loves papaya and jazz was perhaps not as incongruous as I thought. As I ambled my way home in the dark, I found myself singing ���The Bare Necessities��� in my head, and I was happy to have revisited this childhood classic.

May 2, 2016

April 29, 2016

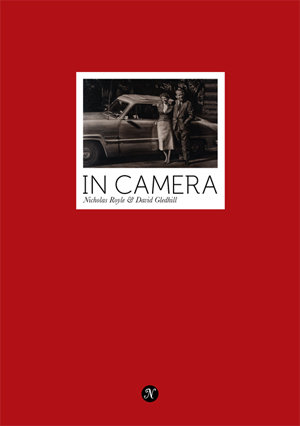

Snap!

Look at this jolly chap ��� can you believe he was found abandoned in a flea market in Frankfurt? Or at least, some version was found there, by the painter David Gledhill, in an East German family album . . . .

How wonderfully fruitful such second-hand seedlings can be. Gledhill produced a series of oil paintings based on this ordinary collection of snapshots from the 1950s, and asked the writer Nicholas Royle to conjure a story out of the paintings. In Camera is the excellent result of their collaboration: published by Negative Press, which exists for the purpose of encouraging works that each take "a unique approach to mixing art and writing", it matches each of Gledhill's paintings to an answering page by Royle. A comic story emerges, told from a child's point of view. It turns on her curiosity about her father's newfangled camera:

"Not long after Father took up photography, I would sometimes come across his camera left lying around the house . . . . I was curious about this device, which on occasion he had allowed me and J to hold, but only as long as we were very careful and didn't press what he called the shutter. At night I would talk to S . . . about this shutter. She said [it] was a secret portal to another world . . . ."

A surreptitious take-over follows, reflecting Gledhill's adoption of the homeless snapshots that inspired In Camera. And there's also a gently sinister spin here, perhaps, on the Isherwood ideal of passively recorded material, that "Some day . . . will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed", as the girl's own version of events is framed by various adult ones. After all, Father, pictured above beaming in his armchair, is a citizen of the Deutsche Demokratische Republik, and a doctor ��� the Stasi were not above approaching medical professionals as potentially useful informants. (How many doctors were involved, and how they were involved, with the Stasi has been, I'm told, a matter of hot historical dispute.)

Perhaps you could call In Camera an eccentric form of ekphrasis. In strict classical terms, that term refers to the description of a work of art in words, as in Homer's mighty description of the Shield of Achilles in the Iliad. The habit of stretching that definition is an age-old one, though; it takes in exalted poems such as Keats's "Ode on a Grecian Urn", Browning's "My Last Duchess" (imagined ekphrasis; Browning being, incidentally, the subject of the latest episode of TLS Voices) and Larkin's "Arundel Tomb". (You can find many more examples via the Poetry Foundation, by the way: "The Broken Fountain" by Amy Lowell, "In Goya's Greatest Scenes We Seem To See . . ." by Lawrence Ferlinghetti, "Tapestry" by Charles Simic, "Edward Hopper Study: Hotel room" by Victoria Chang, and more.)

Prose examples crop up everywhere, but whole books based on the same idea are rarer: they include Brigid Brophy's Prince and the Wild Geese, a story set to the graceful drawings of Prince Grigory Gagarin, and the National Portrait Gallery's Imagined Portraits, accompanying an exhibition of the same name. More recently, in Exchange, Chris Drury and Kay Syrad describe an unusual rural situation, that of three farms in West Dorset, in a similarly unusual way, combining Drury's drawings (on paper "matured" in the Dorset soil itself for eighteen months) with Syrad's verse and prose. "Walk along the track to the sheep barn, find the farmer checking udders for damage or disease . . . ."

I participated in a "live" exercise in ekphrasis a few years ago, providing some improvised musical accompaniment to a series of slides, again of domestic scenes, to which actors ad-libbed stories. (The slides being drawn from a collection some 5,000-strong that originated in another flea market, in Berlin this time.) The stories grew increasingly absurd with each click-and-slide of the projector, as domestic interiors gave way to mountainsides. The audience had long given up trying to make sense of all this, I expect, by the time we found ourselves in a submarine.

But at least this officially makes In Camera part of a noble artistic tradition. "We are all rootling around the flea market, but some of us are looking at the Stasi . . . ."

Hitler and the Zionists

Ken Livingstone, 2016 �� Jack Hill

By TOBY LICHTIG

Amid all the outcry and ill feeling surrounding Ken Livingstone���s Hitler-was-a-Zionist ���gaffe���, it���s probably worth referring to a few historical facts. I���m not sure which history book the former London mayor has been reading, but it presumably isn���t Peter Longerich���s Holocaust (2010), in which we can find (on page 67, should Livingstone wish to consult it) a very clear explanation of the Reich���s policy on Palestine:

���on 16 January 1937 [well before Hitler, in Livingstone���s estimation, ���went mad���] the Reich Minister of the Interior informed the German Foreign Office that it was planning to continue to support the policy of Jewish emigration regardless of the destination countries [including Palestine]. But after it began to emerge in early 1937 that Britain���s Peel Commission might opt for a Jewish state in Palestine, on 1 June the Foreign Minister, Neurath, sent guidelines to the embassies in London and Baghdad and to the Consul General in Jerusalem in which he made it crystal clear that he was against the formulation of a Jewish state or ���anything resembling that state������.

In other words, and not surprisingly, the Nazi Party was not happy, in the words of Longerich, with the idea of ���an internationally recognized power base for world Jewry���.

It is true that Adolf Eichmann visited Palestine, also in 1937, to promote ���Zionist emigration of Jews from Germany���, as well as to keep a close eye on the Zionist organizations in the British Mandate, and perhaps this confused Livingstone, who apparently fails to understand the difference between Hitler���s desire to get rid of his Jewish population as quickly and efficiently as possible and a sincere concern for the desirability for nationhood of a much persecuted ethno-religious group.

Perhaps Livingstone was also thinking about the arguably ���fascist��� ��� although certainly not Nazi ��� elements of certain Zionist factions in the years leading up to the formation of the Jewish State in 1948 and beyond. It is interesting to note, for example, that Benito Mussolini, whose own anti-Semitism was born more of political expediency than ideological fervour, praised Vladimir Jabotinsky ��� the founder of Revisionist Zionism and the father to today���s Likud Party, currently in power in Israel ��� as a ���Jewish fascist���.

Vladimir Jabotinsky (centre). �� FPG/Getty Images)

Certainly, there was plenty of talk of Jewish sweat and Jewish soil and Jewish exceptionalism in a specifically Jewish state. Indeed, it would have been surprising if a nationalist movement at that time hadn���t, in its most extreme manifestations, taken on some of the characteristics of the fascism so in vogue. In December 1948, a few months after the formation of the Israeli State, Albert Einstein, who knew a thing or two about the terrible effects of right-wing politics, wrote to the New York Times to complain about one of ���the most disturbing political phenomena of our times��� ��� the new Israeli Freedom Party (also the precursor to today���s Likud), which he described as ���closely akin in its organization, methods, political philosophy and social appeal to the Nazi and Fascist Parties���. There is a genuine debate to be had about the fascist strains in certain ��� and I stress certain ��� elements of early Zionist ideology, even if that ideology was born of the desire to escape oppression. But regardless of the context in which Livingstone was speaking, and apart from anything else about this sorry episode, he does us no favours at all by getting history so badly wrong.

Perhaps the former mayor was also confused by the term ���Hitler Zionist��� ��� a pejorative used in the 1950s and 60s by the Zionist pioneers (���Sabras���) who had been in the country for several decades, or were born there, to refer to those who had merely been forced into their ���Zionism��� by dint of their expulsion by Hitler. If so, he might again wish to consider the difference between ejection and nation-building.

Whatever the case, what no part of Ken Livingstone���s little indiscretion does is encourage people to be clear-headed about the very distinct and salient differences between Zionism in the 1930s; Zionist ideology in the twenty-first century ��� the original aim of Herzl���s Zionist project having been emphatically attained; and the foreign and domestic policies of the current and recent Israeli governments. Nor, for that matter, does it help us to consider the various differences between Jews of the diaspora, with their multiplicity of views on Israel; Israeli Jews who support a two-state solution; those who support a one-state one; Zionist settlers who believe in a greater Israel; and Israeli Arabs ��� as opposed to the long-suffering Palestinians of the Occupied Territories ��� who so often tend to get forgotten in discussions about Israel: which is to say, the Arabs who are represented by a robust, if troubled, democracy, with MPs in the Knesset.

But, then, nuance isn���t one of the most noteworthy features of contemporary discourse on Israel���Palestine, whether or not it is used as a smokescreen for anti-Semitism. We can only hope that the rightful widespread outrage about Ken Livingstone���s foolishness or ��� possibly ��� racism does not itself get co-opted to drown out the very many nuances of this most vexed of political issues: an issue whose very vexedness ��� in comparison to, say, the rather more muted outrage expressed daily at human rights abuses in Sudan or Equatorial Guinea or even that other great Western ally in the region, Saudi Arabia ��� is itself in danger of transmuting from a justifiable concern for the wellbeing and need for nationhood of the Palestinian people into something far more worrying and obsessional.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers