Peter Stothard's Blog, page 3

August 7, 2016

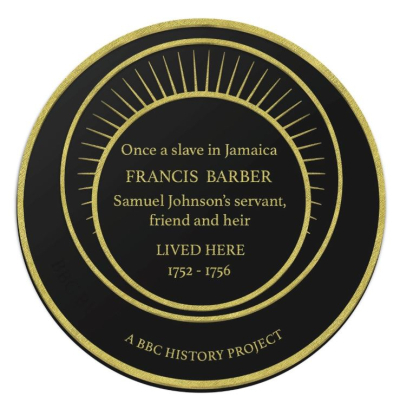

A plaque for Francis Barber at Dr Johnson's house

By ROBERT DEMARIA

On July 28, about a hundred people gathered at Dr Johnson���s House at 17 Gough Square, off Fleet Street in London, to witness the unveiling of a plaque commemorating the life of Francis Barber, a West Indian freed slave who was a member of Johnson���s household and his residuary legatee. The plaque is one of several being placed at sites in the UK, former colonies and the Commonwealth in connection with a four-part BBC television series about Britons of African origin on both sides of the Atlantic. The series traces the presence of Africans in Britain from Roman times, through the years of slave trading in the Western Hemisphere, and into modern times.

David Olusoga, the writer and presenter of the BBC series, and his crew were at Dr Johnson���s House for most of the day, trying to capture on film the situation in which Barber lived and to get some sense of the remarkable ���Modern Family��� of which he was a part in Gough Square.

Colonel Richard Bathurst brought Barber with him to London around 1750 after the sale of his plantation in Jamaica, where Barber was born into slavery. Almost all the other slaves were sold along with the plantation, and Barber���s special treatment has raised speculation that he was the son of the plantation owner and therefore the half-brother of Johnson���s close friend (also called Richard Bathurst). Francis was put in Johnson���s care in 1752, shortly after the death of Mrs Johnson.

When Colonel Bathurst died in 1755, he left Barber his freedom in his will, although whether or not this changed his legal status is not clear. Barber had not lived in England as a slave; he was a servant and a tutee in Johnson���s house; but his freedom was nonetheless supremely important. In 1762, Richard Bathurst died at the siege of Havanna, where he served as a military doctor, and this may have intensified Johnson���s commitment to Barber. Johnson sorely lamented Bathurst���s death, vehemently declaring that all the territories won in the battle were not worth the life of his friend. Although Johnson thought highly of the effort to bring the benefits of Christianity to all parts of the world, he was strongly against colonial expansion; he deplored colonial cruelty, and he was profoundly opposed to slavery, which he regarded as dangerous to moral, spiritual and civic life. His toast while dining with ���some grave men��� at Oxford ���to the next insurrection of the negroes in the West Indies��� is well known, but even earlier, in the 1750s, while composing his Dictionary, he paused when he came to the word ���caitiff" and reflected on its signification as both a bad man and a slave; then, he inserted a Greek distich deploring slavery because it diminishes morality. In 1776, reacting to revolutionary activity in the American colonies, he asked trenchantly why ���we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of the Negroes���.

When Barber arrived at 17 Gough Square at the age of six or seven, Johnson and his amanuenses were at work on the great Dictionary. Johnson helped Barber to get an education, tutoring him himself and eventually sending him to a boarding school. The two lived together on and off through Barber���s youth, which included a stint in the Royal Navy and a period of service with an apothecary in the City. Johnson himself was somewhat itinerant for several years after leaving Gough Square in 1759, but he eventually settled down in Johnson Court and then in nearby Bolt Court. Barber, who was by this time married, shared his house again as an adult.

Barber���s marriage to a white British woman was controversial in Johnson���s circle, but Johnson had no qualms about welcoming Frank, his wife, and their children into his life. As far as I know, Johnson never spoke about his inclusion of Frank and his family as an act of special virtue on his part. He benefited from Frank���s presence, and he was no more critical of Barber���s status than he was of the status of the other denizens of his household: Anna, the blind daughter of the experimenter Zachariah Williams; Elizabeth Desmoulins, a former caretaker of his wife; Polly Carmichael, a former prostitute; and Robert Levett, a largely self-educated doctor to the poor. This was not by any means a harmonious group, and each had his or her problems, but they stayed together for a long time, and Johnson felt indebted to each for various reasons.

Many of Johnson���s companions died before he did. By the end, Barber was almost the only one remaining, and he was certainly the youngest. When Johnson died in 1784, he left Barber about ��1,500 and many of his worldly effects. Johnson named Barber as his residuary legatee over the objections of his executor and attorney Sir John Hawkins, who expressed his prejudicial views in his biography of Johnson in 1787. With his inheritance Barber moved his family to Lichfield, where he opened a school, becoming perhaps the first black schoolmaster in Britain. Like Johnson���s school in Lichfield in the 1730s, Barber���s failed, and he was eventually forced to sell many of Johnson���s effects. His family thrived nevertheless, and he left children and grandchildren behind when he died in 1801.

At Thursday���s celebration, Cedric Barber, Francis���s direct heir of the seventh generation, was on hand to whisk the veil from the plaque and to speak briefly about his family���s connection to Johnson. He was joined by Celine Luppo McDaid, the curator of Dr Johnson���s House, and by Michael Bundock, the author of the recent authoritative biography, The Fortunes of Francis Barber (2015), which is now the definitive source of information on Barber (including the information presented in this article).

After richly deserved applause, the assembled group of Johnsonians, including many patrons, directors and governors of the House, went inside to drink a toast to the memories of Francis Barber and his unlikely master turned employer turned lifelong friend, Samuel Johnson.

The BBC series A Black History of Britain will air this autumn.

Unveiling the plaque: Celine Luppo McDaid, Cedric Barber and Michael Bundock

August 5, 2016

Apollinaire, the painter's poet

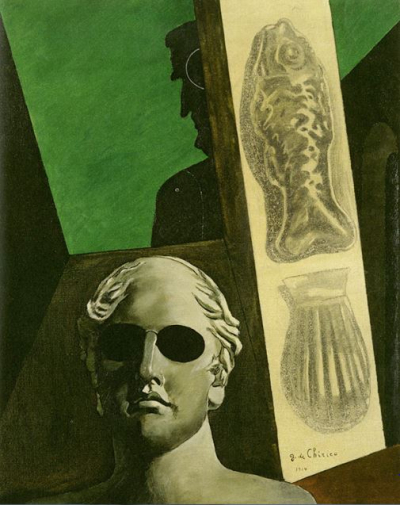

Giorgio De Chirico���s ���Premonitory Portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire��� (1914; oil and charcoal on canvas)

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

���J���ai tant aim�� les arts que je suis artilleur���, Apollinaire wrote in 1916 ��� I���ve so loved the arts that I���m an artilleryman (a pre-echo perhaps of the Killers��� line ���I got soul but I���m not a soldier���?)

Was there a twentieth-century poet more painted than Apollinaire? There are numerous portraits by Picasso ��� the two men met in 1905 and remained firm friends until the poet���s death at the age of thirty-eight from Spanish flu only a few days before the Armistice in November 1918. Picasso, who had provided a Cubist portrait of the poet for the frontispiece of his collection Alcools (1913), was said to be grief-stricken.

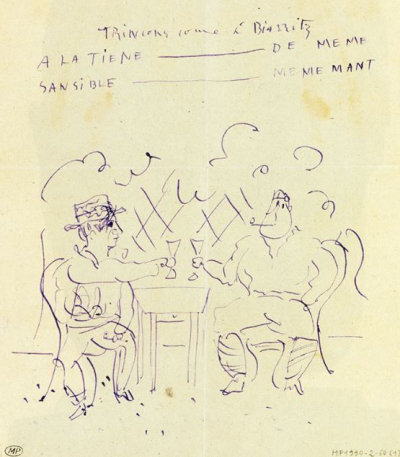

Picasso: ���Picasso and Apollinaire clinking glasses��� ��� drawing on a letter Picasso sent to the poet in the summer of 1918

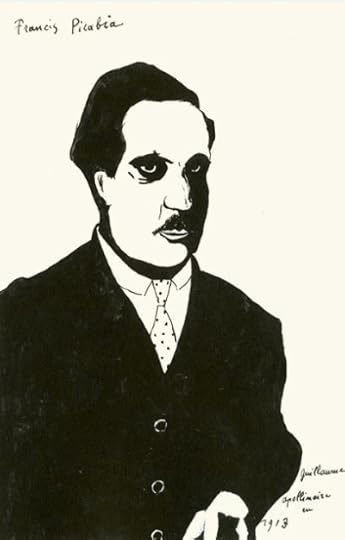

A recent exhibition at the Mus��e de l���Orangerie in Paris, Apollinaire: Le regard du po��te, focused on the poet���s fruitful relationships with his artistic peers, and his serious engagement with the art of his time, championing the work of Douanier Rousseau, for example ��� Paris was unquestionably the world capital of art at the time. Apart from work by Picasso, on display were portraits by Giorgio De Chirico (before his return to Italy to sign up), Francis Picabia, Sonia Delaunay, Marc Chagall, Robert Delaunay, Jean Metzinger, Louis Marcoussis (the comical ���Apollinaire in Prison��� in the wake of the Mona Lisa episode in 1911), Marie Laurencin (including the wonderful ���Group of Artists��� of 1908, which also features Picasso, Laurencin herself, and Picasso���s companion Fernande Olivier), Marcel Duchamp and Henri Matisse (an eye-catching charcoal work dated 1944). Raoul Dufy, meanwhile, had provided woodcuts for Apollinaire���s collection Le Bestiaire (1911).

Francis Picabia: Apollinaire in 1913

Added to which were numerous works Apollinaire had written about or championed in the Soir��es de Paris magazine, which he co-founded in 1912. Then there is his interest in the circus, in cinema (Louis Feuillade's poster image of Fant��mas massively straddling the rooftops of Paris). And not least was the interest he shared with Picasso in ���art n��gre��� or ���primitive��� art, which he fed by visiting the Trocad��ro museum. (The museum closed in 1935, but in its stead Paris now boasts the superb museum at the Quai Branly, which displays the indigenous art and cultures of Africa, Asia, the Americas and Oceania; it was opened, somewhat surprisingly, by President Jacques Chirac, and has recently celebrated its tenth anniversary.)

To coincide with the exhibition, Gallimard published an edition of the mostly unpublished correspondence between him and the art dealer Paul Guillaume (some 120 letters, the majority from Guillaume to Apollinaire). The work has been meticulously edited by the TLS contributor Peter Read. Apollinaire and Guillaume met in 1911 when the latter was just nineteen. Within ten years he had become ���one of the most influential and enlightened art dealers of his time���. As Read and Laurence Campa write in their introduction, the two men, ���in spite of their differences, . . . collaborated . . . in a magnificent series of exhibitions, events and publications���.

Guillaume is often ��� it has to be said ��� demanding, disappointed at the poet���s non-appearance. (Apollinaire���s own first letter to the art dealer is no. 17 in the correspondence: ���Received from Mister PAUL GUILLAUME the sum of TEN francs for the publicity in the June issue of SOIR��ES de PARIS���.) By 1915 the poet has signed up and is at the front, where, as contact man, he rides around on a horse behind the lines. In May of that year he writes to Guillaume from the front to thank him for cigars. ���Here it���s always the same, combats in which we don���t see the enemy, we sense him, we see the shells that he sends over and during the night the rockets light up the front, the searchlights . . . . It���s enchanting��� (these experiences were worked into his poetry). Guillaume replies to reveal that he has become ���Plenipotentiary of modern art in Paris���. He offers no specific comment on the poet���s report from the front beyond a request for ���frequent news��� as it gives him ���the greatest pleasure���. By September Guillaume is wondering ���what has become of [him]?��� He���s heard that he may have been promoted to sergeant, but as he���s not certain he decides not to address him thus on his envelope. (Apollinaire, meanwhile, refers to Germany as ���Bocherie���.)

(Attributed to) Serge F��rat, after a photograph taken at the H��pital italien on the quai d���Orsay (1916)

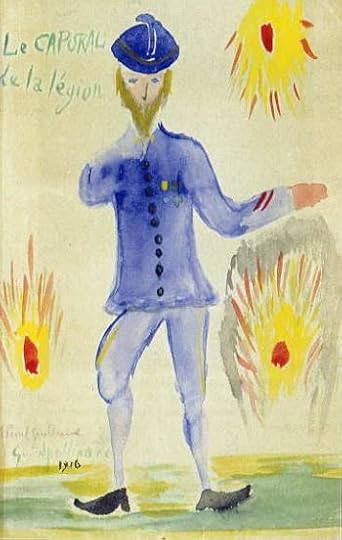

In May 1916 following a head wound received at the front the poet undergoes a trepanning (curiously Read gives the date as May 1915 in a note). During his convalescence Apollinaire paints the wonderful watercolour ���Le Caporal de la l��gion", a portrait of the poet and adventurer Blaise Cendrars, who had himself lost an arm in the conflict (below).

Paul Guillaume kept his poet busy. In January 1918 he commissioned Apollinaire (who was bed-ridden with a chest infection) to write the preface to a catalogue of an imminent Picasso/Matisse exhibition. The poet delivered an eloquent text. In May 1918, meanwhile, Picasso was a witness at Apollinaire���s wedding to Jacqueline Kolb and gave them ���L���Homme �� la guitare��� which took pride of place on the walls of their apartment on the Boulevard Saint-Germain. Sadly, the last letter from the poet to Paul Guillaume included here, dated October 11, 1918, accuses its recipient of loutish behaviour ��� "Votre conduite vis-��-vis de moi est celle d'un fort grand voyou". Within a month Apollinaire would be dead.

Related articles

The Marquis de Sade 200 years on

The Marquis de Sade 200 years on

August 3, 2016

Dystopian fictions in the time of Trump: A letter from America

By JEFFREY WASSERSTROM

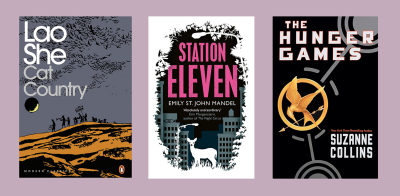

I���m not sure why others read dystopian novels, but I know why I turn to them ��� and why, thanks to Donald Trump���s candidacy, I���ve recently found myself abandoning ones midway through that had come to me highly recommended. For me, the allure of thought-provoking dystopian novels ��� from classics such as Aldous Huxley���s Brave New World (1932) to powerful recent works such as Emily St. John Mandel���s Station Eleven (2014) ��� is twofold. They provide new ways of thinking about contemporary problems, yet offer a degree of escape from them. The difficulty now is that dystopian works of art ��� films as well as novels ��� don't give me relief from a singularly distressing news cycle, dominated both by reports of horrific violence and by an American election that has inspired more conjuring of nightmarish scenarios than any past one.

Some commentators present a Trump presidency as sending the United States in a dystopian direction. Analysts invoke the troubling visions of an authoritarian America found in novels such as Philip Roth���s The Plot Against America (2004) and, long before that, Sinclair Lewis���s It Can���t Happen Here (1935). Trump���s acceptance speech, meanwhile, was described by everyone from late-night comics to political analysts and newscasters as presenting the country���s current state in darkly dystopian terms. (Perhaps owing to the comparative scarcity of the word dystopian in coverage of past political speeches, some felt the need to define it as the opposite of utopian.)

In addition to reading dystopian fiction for pleasure, I have often brought it into my work on China, and found it useful, in doing this, to distinguish between three general varieties. There is the Big Brother type, involving a ruling strongman and, as George Orwell put it in Nineteen Eighty Four (1949), a ���boot stamping on a human face ��� for ever��� approach to control. Then there is the softer authoritarianism of Brave New World, in which the powerful retain control by providing material comforts and deeply distracting forms of entertainment to the masses, while also ensuring that different groups view one another with disdain. Finally, there is the lawlessness of Lord of the Flies (1954). There is no iconic Western exemplar for this kind of novel from the first half of the last century, but China provides one in Lao She���s Cat Country (1932), which I discussed in the TLS on the publication of a new edition, with an excellent introduction by Ian Johnson).

Elements of the first two varieties are blended in many works: in the Hunger Games books and films, for example, life in the capital has a Brave New World side while in other districts, the system of control is boot-on-the-face; and, in a Chinese context, while Chan Koonchung���s The Fat Years (2009) has been marketed as a work with much in common with Nineteen Eighty Four, it is only Huxley's name, not Orwell's, that gets mentioned in passing by one of the novel's characters. Orwell and Huxley both placed a strong, intrusive state at the centre of the nightmare. In the third variety, by contrast, weak state structures fail to keep chaos in check.

Which sorts of dystopian fiction have been in play lately in the US? Asking this feels natural: describing what the country could become under Trump is the sort of imaginative exercise in which novelists routinely engage, while the Republican candidate plays so fast and loose with facts that his speeches lend themselves to literary criticism. The answer is easy when it comes to worrying about Trump���s rise: he is seen as embracing a Big Brother view of governance that would send the country spiralling into the kind of populist-fuelled fascism that Roth and Lewis conjured up in their novels.

Trump���s speech at the Republican National Convention, on the other hand, fits squarely into the tradition of failed-state fiction. He presented the contemporary United States as having descended into the kind of decayed land more commonly found in post-apocalyptic works, from the post-plague Station Eleven to the world of the Mad Max movies. The speech reminded me of Lao She���s Cat Country, which focuses on a feline-run community on Mars clearly meant to represent China in the early 1930s. The Chinese author, best known to Western readers for the very different realist novel Rickshaw Boy (1936), presented his country as a once great place that had declined markedly. In this stand-in for China on the eve of Japanese invasions, all forms of basic infrastructure have decayed, and the rulers of the land are unable to defend it from threatening outsiders.

When I teach about China in the 1930s, I treat Cat Country as providing a caricatured but in some ways apt portrait of a country Lao She longed to see right its course. Trump���s vision of today���s America, though presented as fact rather than fiction, takes too much poetic licence to be handled that way. There is also something that chills me when I reflect on the course of Chinese history from the era of Cat Country���s publication to the present era of the trust-me-to-handle-everything autocrat Xi Jinping. Time and again, that country���s people have suffered, as those of its neighbour Russia have, from the notion that the only way to revive the fortunes of a once great nation is to put its fate in the hands of a tough-talking strong man.

July 31, 2016

BG (Before Granta . . .)

The novel is over ��� and a more "novel" kind of novel is needed. Or at least Bernard Bergonzi suggested as much in The Situation of the Novel, back in 1970. The novelist writing after the Second World War, he wrote, "has inherited a form whose principal character is novelty, or stylistic dynamism, and yet nearly everything possible to be achieved has already been done".

There have been many variants on the same, now far from novel theme. The Bergonzi version has Proust and Joyce as the twin "apotheosis of the realistic novel"; where else was there to go? What on earth would happen next? Clearly a renewal was in order . . . .

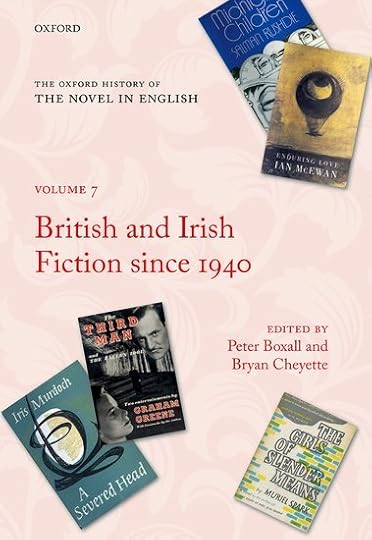

At least as far as the novel in one language is concerned, an alternative means of tracking the progression of the novel over the many years since the glory days of the great modernists is offered in the latest volume of the Oxford History of the Novel in English. Edited by Peter Boxall and Bryan Cheyette, the seventh in this already bulky, impressive series, covers "British and Irish fiction since 1940". It will be reviewed in the TLS in due course; for now, though, it's one of those critical parlour games that catches the eye here: the OHNE editors' retrospective take on the "Best of Young British Novelists" scheme inaugurated by Granta and the British Book Marketing Council in 1983.

In its very first issue, in 1979, Granta proclaimed "the end of the English novel [and] the beginning of British fiction". The new generation was apparently more engaged with the international scene and with theoretical ideas "such as postmodernism, postcolonialism and feminism". The old, insular, "exhausted" lot could hardly hope to compete with all that. Who would replace them?

Well, as a reminder ��� deep breath ��� how about this lot, all under forty years of age at the time?

Martin Amis

Pat Barker

Julian Barnes

Ursula Bentley

William Boyd

Buchi Emecheta

Maggie Gee

Kazuo Ishiguro

Alan Judd

Adam Mars-Jones

Ian McEwan

Shiva Naipaul

Philip Norman

Christopher Priest

Salman Rushdie

Lisa de Ter��n

Clive Sinclair

Graham Swift

Rose Tremain

A. N. Wilson

"Prescient" is the word some have fairly used of the Granta list, and not just in relation to 1983's crop. (1993, 2003 and 2013 aren't bad, either.) What the OHNE editors suggest, however, is that there is a false, "invariably overstated" narrative here of "youth superseding age". The received idea of a "new era in the novel", dating back some thirty or forty years, is "misleading". Take a look at their table of under-forty novelists of the four decades before 1983 who might (ought to?) have been seen at the time as equally promising talents, many of them engaged, in various ways, with "postmodernism, postcolonialism and feminism" as their successors were:

1943

1953

1963

1973

H. E. Bates

Paul Bailey

Anthony Burgess

Stan Barstow

Elizabeth Bowen

John Berger

John Banville

John Braine

Wilson Harris

Pat Barker

William Cooper

Attia Hosain

A. S. Byatt

Malcolm Bradbury

Lawrence Durrell

Elizabeth Jane

Howard

Margaret Drabble

Melvyn Bragg

William Golding

Dan Jacobson

Emecheta Buchi

Henry Green

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

J. G. Farrell

Graham Greene

Francis King

David Caute

Arthur Koestler

George Lamming

P. D. James

Zo�� Fairbairns

Rosamund Lehmann

Elaine Feinstein

Malcolm Lowry

Colin MacInnes

John Le Carr��

Eva Figes

Olivia Manning

Brian Moore

David Lodge

Michael Frayn

Mervyn Peake

Nicholas Moseley

John McGahern

Gordon Giles

Stanley Middleton

Susan Hill

V. S. Pritchett

Barbara Pym

V. S. Naipaul

Gabriel Josipovici

Samuel Selvon

Edna O���Brien

Robert Nye

George Orwell

Paul Scott

Bernice Rubens

Christopher Priest

C. P. Snow

John Wain

Alan Sillitoe

Emma Tennant

Angus Wilson

William Trevor

Rose Tremain

Boxall and Cheyette's introductory account of the post-war novel is freely available to read online; I'll merely add that literary forms seem to be constantly dying and reviving, as the short story does with tedious circularity. And that even if the OHNE's contentions about the course of literary history don't convince you, it's not a bad way of reminding yourself of the literary eclecticism of recent times. B. S. Johnson, P. D. James, J. G. Ballard and Margaret Drabble at work in the same decade doesn't sound to me like bad going for a genre that's supposedly dead in the water.

July 30, 2016

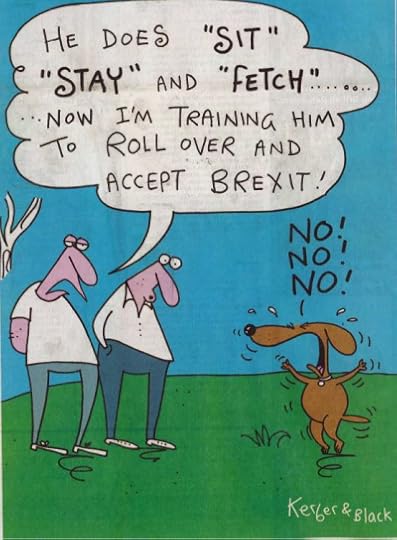

Banging on about Europe

A cartoon from the pop-up newspaper The New European

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

���Banging on about Europe��� was what David Cameron (remember him?) pledged back in 2010 he would stop the Conservatives from doing. He hoped to achieve this by promising a referendum on the UK���s membership in the European Union. It is said that Cameron never expected to win the general election in 2015 outright but rather that the Conservatives would probably end up in coalition with the Liberal Democrats again. Did he have a slight sense of foreboding when he realized that, with the surprising outright victory, he would have to deliver the referendum, or was he absolutely confident that the Remain camp would prevail? Or did he really believe ��� as he asserted to his fellow European leaders in March ��� that the Remainers had it in the bag because he ���was a winner���? I guess we may find out one day when the history of the tumultuous past few months in British politics comes to be written.

Events have moved so quickly that it���s easy to forget that in the post-Cameron/Osborne landscape we were faced with the prospect of a Boris Johnson premiership. The writer and political columnist Harry Mount wrote in the London Evening Standard on June 24: ���The age of Cameron and Osborne is giving way to the age of Johnson alone���. Cameron could not withstand ���the blond exocet missile now aimed at the front door of No 10���, he went on. The Exocet has, thankfully, been intercepted ��� for the time being at least, or redirected to the Foreign Office where it can do only a limited amount of damage.

Three days later, again in the Standard, Mount wrote that the referendum result had ���triggered a mass outbreak of bad losers who won���t accept the result���. Pointing out that 3.5 million voters had signed a petition demanding a second vote, Mount wrote that ���the bad losers can���t accept that the rest of the world doesn���t agree with them . . . . In democracies, the people can���t be told how to vote ��� or told to try again if they produce the wrong result. It isn���t a difficult concept to handle, whatever age or class you are���.

But the Remainers can accept the result, and have done so! No one has seriously suggested there should be a second referendum ��� I imagine many of the signatories to that petition signed out of a sense of frustration rather than in the expectation of a second referendum.

Meanwhile, in the Times on July 21, Tim Montgomerie complained about ���Remoaning nonsense��� (do I detect light abuse there?). The Times published a good riposte to Montgomerie on its Letters page (July 22) from James Shillady of London SW15, who took exception to Montgomerie���s suggestion that Remainers should ���be denied the right to fight against or to seek to modify Brexit and every aspect of its implementation���. I particularly like his conclusion: ���Had we just lost a general election we would not now be expected to profess our support for the winning party���s manifesto . . . . It is called opposition and the Leavers should get used to the idea that there will be plenty of it���.

And a very visible manifestation of this opposition comes in the form of the New European, the self-styled ���new pop-up paper for the 48%��� (who voted Remain). Quick off the mark, the weekly, which sold 40,000 copies on its launch, has already brought out its fourth edition, and costs ��2 or ������3 (where sold in the Eurozone)���.

It seems almost calculated to raise the hackles of the Brexiters: there have been articles by Howard Jacobson on ���Racism, Brexit and Fear���, Hardeep Singh Koli writing under the rubric ���Expertise��� (which contains the witty tagline ������People in this country have had enough of experts��� ��� Michael Gove���) on the ���dearth of diversity in our media���, which is perhaps slightly off the point. A. C. Grayling, meanwhile, suggests that far from it being ���anti-democratic to debate this bad referendum, . . . shutting up and accepting it is wrong���. In the most recent issue (July 29���Aug 4), the distinguished Professor of the History of the Church at Oxford Diarmaid MacCulloch explains why the sixteenth-century Reformation instigated by Henry VIII (���the old monster���) was ���not the first Brexit���. MacCulloch suggests that the Reformation offers history lessons: ���Those who remember the Reformation aright should resist breaking the natural wider ties in our Continent���.

July 29, 2016

Samuel Lock ��� fighting for the spirit

Sam Lock in Lefkada; photograph by Jonathan Dove

By ALAN JENKINS

���Very odd and original��� was the way Alan Hollinghurst described one of his Books of the Year in 1995: As Luck Would Have It by Samuel Lock. And indeed Lock, who died earlier his month at the age of ninety, was one of the oddest and most original novelists of his time. But what was ���his time���, exactly? Speaking at his funeral, Hollinghurst recalled being ���captivated by something that was oddly both contemporary and old-fashioned��� about As Luck Would Have It, the first of Lock���s three strikingly different novels to be published. The same could be said of all of the novels.

They appeared at three-year intervals between 1995 (when Lock was sixty-nine) and 2001; the last, The Whites of Gold, begins ���It is 1969���. But it is still very much the post-war era that they inhabit: a world of shared flats and bedsits in 1950s Kensington and Chelsea, with excursions to the south coast and the pre-war west country ��� on the face of it, a world of respectability, frugality and making-do (Larkin���s ���small blameless comforts���), before sexual intercourse began, before Swinging London, and long before the Sexual Offences Act of 1967, which decriminalized homosexual acts in private between consenting adult males. For in all Lock���s novels this is, predominantly, a world of males, and consenting if not always fully adult ones; men whose deepest motives and desires are obscure even to themselves and whose inner lives ��� ���the vein of rich, unfolding narrative within us���, which interests Lock far more than the externals of ���period��� detail or convention ��� are a kind of battleground between the potent forces of guilt and repression, and the urgings of the hidden self towards self-knowledge and fulfilment. Privacy, reticence and kindness are all valued, and all equally subject to sudden, alarming eruptions of impulse and appetite, violent, irrational, unbiddable ��� with comic, poignant and in one case terrible consequences.

It was Hollinghurst who gave me a copy of As Luck Would Have It, and introduced me to Sam himself not much later. I was very much taken with the novel and equally so with the novelist, a spry, sprucely turned-out and bewilderingly youthful septuagenarian whose eyes gleamed with insight and mischief. I was soon charmed, as many others were, by his gently inquisitive manner and his residual west-county burr (he was born in Devon, minutes after his identical twin Wilfred, to Sidney Avery and Edith, n��e Lock, and named Samuel after Edith���s brother, killed in the First World War). He had an aura of old-world bohemian distinction, a classless elegance. Such was, as well, the feel of the studio, set squarely on top of an LCC block of flats just off the King���s Road, where Sam had lived since 1956 ��� sharing it first with Wilfred and, from 1960, with his partner, the painter Adrian de Menasce. Adrian had died not long before my first visit; his presence was (and remained) palpable not just in Sam���s conversation but in the paintings, drawings and books that filled every inch of wall- and shelf-space in the ���time-capsule���, as Hollinghurst justly called it, where Sam dispensed gin-and-tonics and smoked-salmon canap��s or served inventive suppers that often featured a mysteriously customized Crosse and Blackwell���s lentil soup.

As a young man Sam had set out to be a painter; this proved to be Wilfred���s calling, while Sam turned his hand to a succession of creative endeavours, as a stage-designer, documentary-maker, scriptwriter and playwright, before, in his mid-sixties, discovering his vocation as a novelist. His deep love of theatre and, especially, cinema had survived what, in his very funny and affectionate stories of the actors, directors, artists and poets who thronged his and Adrian���s Friday-evening ���at homes���, seemed years of thrillingly chancy but perhaps frustrating effort, and he spoke with profound inwardness, and something close to reverence, about painting. This depth and variety of background is surely something shared by the three members of ���that fascinating tribe, the late-flowering novelist��� Hollinghurst invoked ��� the other two were Francis Wyndham and Penelope Fitzgerald: writers who ���by coming to the novel so late. . .emerged as mature and completely individual voices, without showing any obvious allegiance to anyone���. Ivy Compton-Burnett, Angus Wilson and even Joe Orton might all have contributed a fleeting note or flavour to Sam���s writing, but what is really distinctive in it has nothing in common with any of them: ���the meticulous self-correction, the hurdle-like sequence of semi-colons, the simultaneous effect of candour and mystery. He is a keen clarifier ��� ���Worthington ��� the name of a brand of beer��� ��� and a regular reminder (���which, as I have said��� or ���and which you may remember���); but the tone of logical reassurance often gives one the feeling of being at least half in the dark. Sam���s friend, the American poet James Merrill. . . described the effect beautifully as ���the impeccable prosiness of a vivid dream������. (Hollinghurst.)

Photograph by Orlando Gili

And there is a further aspect to Sam���s novels that lay outside the realms of the possible for those earlier explorers of exquisite social agony and forbidden or occluded desire: as Hollinghurst said, ���It���s worth saying too that the specifically homosexual self-confidence declared on the opening page of Sam���s first book persists wonderfully untroubled through all of them ��� Sam wrote a particular kind of gay novel not bothered about being a gay novel at all. Not what he calls in As Luck Would Have It a ���drop-your-trousers book���, but one full of physical frankness when it seemed right, and as a part of his larger insistence on telling the truth���.

The last months of Sam���s life were troubled by illness, and the death of his brother came not long before his own. He was too ill to attend Wilfred���s funeral, so his friends were more than ever mindful to visit him in hospital on the day, and I was one. Offering my condolences I referred sympathetically to his current situation, and what I assumed must be the sadness and frustration it occasioned him. ���It���s a pity but I can���t be cross, or anything like that���, came Sam���s reply. ���All our lives we fought for the spirit. And we found a higher life.���

July 28, 2016

The Man Booker ��� a TLS longlist

By TOBY LICHTIG

There is always a disjunction, when it comes to literary prizes, between the parameters adhered to by the judges and those demanded by the audience ��� not least for a prize as open to interpretation as the Man Booker.

The task of the panel is simple: to select what its members agree to be ���the best��� English-language novels to have been published in the UK over the past year. But what we, the public, tend to clamour for is something closer to a cross-section. When it comes to a long list, we demand balance, a range of different voices, themes and settings; of different nationalities and genres. Conversely, we also like to spot patterns and trends (a terrible journalistic habit). And of course we���re all hopelessly partisan about our own choices. Who has ever seen a longlist, or a shortlist for that matter, and genuinely thought: yes, those are exactly the ones I would have chosen?

When it comes to the Man Booker I���m firmly with Julian Barnes on the ���posh bingo��� front. As I discussed last night on Front Row with Alex Clark and John Wilson, this year���s is a particularly surprising list, blindsiding the critics with several novels that have barely been reviewed in the British press. Having not seen all 155 submitted books ��� and having, frankly, not read many of the ones on the current list ��� it would be unfair of me to criticize the choices. But while many of the entries are no doubt worthy of recognition, I could quite imagine an alternative reality in which all of these thirteen were replaced by thirteen deserving others. And certainly the list as a whole looks a little narrow to me. Everyone on it is either North American or British, with the exception of J. M. Coetzee, who represents the whole of Africa and Australasia. There are no Irish writers and no Asian ones (Madeleine Thien is a Canadian of Chinese parentage). There are fewer doorstops this year than in previous ones, and fewer sweeping narratives, with an emphasis on the family, the domestic.

So in the spirit of both inclusiveness and partisanship, I���ve decided to jot down a little selection of my own thirteen ���top��� novels from the past year. Of the Man Booker longlist, I���ve included three: David Szalay���s All That Man Is, Paul Beatty���s The Sellout and Madeleine Thien���s Do Not Say We Have Nothing ��� all excellent choices in my opinion. I haven���t yet received proofs of the new J. M. Coetzee novel, The Childhood of Jesus, and so I can���t in all good faith include this; but I have chosen, as a replacement, a novel by another author resident in Australia, Jack Cox. Unlike the Man Booker panel I���ve managed to include a couple of Irish novelists, as well as one at least partially representing Asia (Aravind Adiga, who was born in Madras and grew up in Australia). The Edna O���Brien inclusion is a bit of a cheat, as it���s technically a collection of linked stories ��� but then so too is David Szalay���s book, which was deemed kosher by the judges. And I���ve tried to include a little bit more experimental writing than did this year���s committee, in the forms of John Keene and Eimear McBride, as well as Cox.

All of these books have, naturally, been reviewed in the TLS, except for the ones that haven���t yet come out (or have only just come out) and are set to be reviewed over the coming weeks. And so, in alphabetical order, here there are:

-- Aravind Adiga���s Selection Day: Adiga is one of four debut novelists to have won the prize (for The White Tiger in 2008), which seems to be something of a death knell for literary careers. Neither Keri Hulme (The Bone People, 1985) nor Arundhati Roy (The God of Small Things, 1997) have published another novel since winning. D. B. C. Pierre (Vernon God Little, 2003) has, but his novels have not been especially well-received, and Adiga himself has struggled to achieve the recognition of his debut with his two subsequent books. But Adiga's new novel, out in early September, looks excellent ��� and our reviewer has already written to me to say how much he is enjoying it. Selection Day is set in contemporary Mumbai and features a fourteen-year-old boy struggling to come of age in a domineering and cricket-obsessed family.

-- Paul Beatty's The Sellout: I thought this was an excellent choice by the Man Booker panel. Beatty's satire on race relations in America, featuring an African American protagonist called "Me" who attempts to reinstate slavery and segregation in "agrarian" Los Angeles, is both hilariously funny and entirely on-the-button. Our reviewer, Bill Broun, called it both "inspiring" and, crucially, "much more than 'scathing' ��� it is constructive". And how's this for a funny takedown of black literary stereotypes?: "I'm so fucking tired of black women always being described by their skin tones! Honey-colored this! Dark-chocolate that! My paternal grandmother was mocha-tinged, caf��-au-lait, grahamfucking-cracker brown! How come they never describe white characters in relation to foodstuff and hot liquids?

-- Jack Cox's Dodge Rose: Wildly inventive, hugely tricksy and excellent fun all round, Cox's novel gets my vote for its ability to stretch language and test the reader. The novel is split into two sections, one featuring a young woman growing up in 1920s Sydney, the other focused on the woman's heirs, as they pick through her vast inventory of belongings some sixty years later. Paul Griffiths will be reviewing it in the TLS next month. He calls it: "Brilliant and dark, mysterious and immediate, moving and maddening, disturbing and entertaining . . . [an] extraordinary first novel that compacts the histories of a continent and of a family into a dazzle of two hundred pages."

-- John Keene's Counternarratives: Our reviewer Kate Webb was hugely impressed by this dazzling retelling of colonial history in the Americas, a "writing back" inspired by writers from Jean Rhys to Edward Said but achieved with an unique vision that is all the author's own. "We have", wrote Webb, "become accustomed in recent years to the revisionary spirit of much postcolonial fiction, but the ambition, erudition and epic sweep of John Keene���s remarkable new collection of stories, travelling from the beginnings of modernity to modernism, place it in a class of its own.

-- James Kelman's Dirt Road: The 1994 Booker winner's most recent novels features a father and son who go to America in response to a double bereavement, which transmutes, for the teenage boy, into an anxious, illicit road trip into adulthood. Sarah Crown will be reviewing the book in a future edition of the TLS and she is hugely impressed, calling it a "brilliant" and "universal" book: "quietly, subtly Kelman peels back the veil of daily life to reveal the urgent struggle of a sixteen-year-old coming to terms with death".

-- Eimear McBride' s The Lesser Bohemians: The exclusion of this novel from the 2016 Man Booker is, to my mind, the biggest miss of the lot and a crime to literature. Eimear McBride's brilliant follow-up to A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing, concerns a torrid love affair between an undergraduate drama student and an actor twice her age. It is sexy, urgent, moving, linguistically dazzling and filled with dramatic turns. The TLS will be featuring an exclusive extract from the book next month, and we will be reviewing it when it is published in September.

-- C. E. Morgan's The Sport of Kings: Somewhat oddly, two American "equestrian" books could easily have made the Man Booker longlist this year. Mary Gaitskill's The Mare was reviewed by D. J. Taylor in last week's TLS, and enjoyed by him for its wry, rueful treatment of American middle-class guilt; but it was Morgan's novel from earlier in the year that really sparked this paper's interest. Michael LaPointe noticed a new trend of American female authors producing "long, sprawling, ambitious novels" and concluded that Morgan had triumphantly joined their ranks with this "constantly invigorating, surprising and transfixing novel" about the scion of a farming dynasty who wishes to transform his family's corn fields into a breeding ground for race horses.

-- Sarah Moss's The Tidal Zone: It is hard to say, exactly, what makes Sarah Moss so special. She doesn't do anything particularly showy. Her settings are fairly small canvas. Not that much tends to happen ��� even when Moss moves her action between centuries, or sets her narratives in Greenland. She's just a very very good writer, and her latest novel, The Tidal Zone, in which an anxious father tends to his teenage daughter after she suffers an idiopathic cardiac arrest, is perhaps her best to date. Set against a backdrop of austerity Britain it entwines the father's anxieties with those of the wider nation. Our reviewer, Jonathan Gibbs, found great pleasure in the novel's "studied contemporaneity": "Moss, you feel, sees clearly where we are just now".

-- Edna O���Brien's The Little Red Chairs: Yes, it's technically a collection of interlinked short stories but, frankly, so is David Szalay's All That Man Is (see below) so I'm including it. O'Brien's book moves between Ireland and the Balkans, in what Lindsay Duguid described as "a compelling portrait of a world fractured by guilt and sorrow . . . . The narrative moves swiftly between the past and present tense, first person and third, in short sections and long chapters, mixing vague dreams and vivid memories with sharp scene-setting and close-up enactions of horror."

-- Annie Proulx's The Barkskins: We needed a least one doorstopping behemoth in the list, and what better one to choose than Proulx's epic take on loggers and conservationists set across Canada, the US, China and New Zealand. Our very own Editor Stig Abell praised Proulx���s use of metaphor, her lack of sentimentality and, above, the boldness of her vision: "Proulx has written a huge and brilliant novel, which takes us back to the uncompromising splendour of the natural world, and affirms her reputation as one of the greatest and toughest prose stylists writing today."

-- Francis Spufford's Golden Hill: The Man Booker long list is light on older historical novels (a bit of nineteenth-century whaling aside) and so I thought Spufford's entertaining book deserved a shot. A picaresque tale of an Englishman's misadventure in eighteenth-century Manhattan, it draws on Sterne, Smollett and the Fieldings (Henry and Sarah), and is written in the rhythms and diction of its setting's era. "Spufford���s exuberance and erudition are a wonderful combination", wrote Norma Clarke in the TLS. "The narrative never flags and nor does the sense that we are in several worlds at once, parlours with young women and prison cells with mad drunks that we have encountered in novels and films, rooftop escapes that defy credibility, a bonfire night crowd that turns ugly, bent judges, anxious traders, a coffee-house waiter who can respond to orders in at least five languages."

-- David Szalay's All That Man Is: I love this novel, even if it isn't a novel at all. Szalay's collection of nine interlinked stories, each featuring a different man facing a crisis at a different stage of life, zings with wry observations and coheres into a fascinating portrait of troubled (and pusillanimous) masculinity. The stories "are cleverly arranged", wrote Sam Jordison in the TLS, "running from spring to winter, full of ruses and subtle references to each other, to the different stages of life, to growing and waning, to naivety and experience." I was delighted to see this on the long list.

-- Madeleine Thien's: Do Not Say We Have Nothing: Another good choice by the Man Booker panel. Thien's novel concerns a woman who has fled to Canada in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square protests. Looking back on her past, she reflects on the Cultural Revolution and the lives of three musicians caught up in it. It will be reviewed in a future edition of the TLS.

July 27, 2016

Beyond the Home Front

Kate Cook in The Invisible Woman

By JULIE ANDERSON

Elsie Cawser���s comic poem from the Second World War, Salvage Song (or the Housewife���s Dream) ends with the lines, "So now when I hear on the wireless, / Of Hurricanes showing their mettle, / I see in a vision before me, / A Dornier chased by my kettle". The drive for metals to make weapons such as Spitfires required many women to give up useful household items. Cawser���s poem epitomizes the struggles of women on the home front to juggle their domestic needs with the rapacious requirements of a nation at war. The majority of histories written about war tended to focus on women keeping the home fires burning. Many of the preconceptions surrounding women in war have cast them as keepers of the home or carers; roles that demonstrate women���s support of the quintessentially male practice of war.

Britain is currently in the grips of remembering and commemorating the First World War, which was fought and documented by men. Women���s wartime experience during 1914���18 was centred around nursing, epitomized by Vera Brittain���s book, Testament of Youth. The Second World War placed women in the conflict, as the fluid fighting lines and bombing of civilian targets, meant that in some cases, the war came right through their front doors, with devastating effects. Yet women maintained their supporting role, dealing with the impact of war and its aftermath, which included suicide, disability and domestic violence. There were many ways a woman could lose a husband, father or son to war. It became clear to those interested in the subject of women and war that women���s role in war was more complex and less constrained by domesticity than previously thought. War correspondents such as Lee Miller, Martha Gellhorn and later Kate Adie normalised the public presence of women in conflict zones. Female world leaders were unafraid to take centre stage in supporting conflict. In 1986, the world witnessed the incongruous, yet in the light of her role in the Falklands War, unsurprising, image of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, at a NATO camp in Germany clad in a cream coat, headscarf, gloves, and goggles, riding in a Challenger tank. The reaction to a female world leader in close proximity to weapons of war caused one Daily Telegraph reporter to note that she looked like "a cross between Isadora Duncan and Lawrence of Arabia".

Today, women can take up official combatant roles in a number of countries��� armed forces. So the Women and War Festival, a month-long exhibition (ends July 31) presented by the So and So Arts Club in the City of London, reflects this change from supporter to participant. In this festival of drama, music and dance, accompanied by film screenings and talks, women are soldiers, spies, refugees, veterans and victims. They are also mothers, wives, children, nurses, prostitutes and entertainers. This festival explores universal women���s war experiences, yet still retains the profoundly personal experience of an individual caught up in conflict.

As soon as you go into Fredericks Place, you are transported by the arresting and disturbing images of war by photographers Keymea Yazdanian and Alison Baskerville, and the war paintings of Arabella Dorman which occupy the walls of some of the rooms. Many of Dorman���s images of Afghanistan feature groups of girls, a reminder of the danger that growing up in a conflict zone presents to girls threatened by sexual assault, trauma and disruption to their schooling.

Many of the performances on offer are inspired by historical events, which reflects an awareness of the number of roles that women have played in conflict. During the Festival, I learned that Aphra Behn, the seventeenth-century female playwright, also had a career as a spy during the Dutch Wars. In Invisible Woman ��� one of many one-woman shows at the Festival ��� about a female spy during the Second World War, far removed from the worries associated with the loss of one���s saucepans, a woman named Mrs Bishop is sent to France to assist the French Resistance. The actress Kate Cook tells the audience how she used the Mass Observation Archive to research the many roles she takes on during her performance. Cook, demonstrating an extraordinarily wide range, plays at least a dozen characters, from the jolly-hockey-sticks spy Florence to Mrs Bishop���s husband, a wounded war veteran.

The Festival gives a sense of the variety of women���s experiences of war, cutting across class, age, religion, race, and history. No woman���s experience of conflict is the same, yet the unique experience of individual women speaks to a collective understanding of the effect of conflict on women���s lives.

July 26, 2016

Lov Lttrs

By DENNIS DUNCAN

In 1641, the Portuguese merchant and poet Alonso de Alcal�� y Herrera published a work entitled Varios effetos de amor en cinco novelas exemplares ��� Sundry Effects of Love in Five Novellas ��� in which each of the five tales was written without the use of a different vowel. Thus, "Los dos soles de Toledo" ("The Two Suns of Toledo") has no a, "La carro��a con las damas" ("A Coachful of Gals") no e, and so on. The work is a tour de force ��� Herrera includes poems, songs, and snippets of dramatic dialogue within his narratives, all conforming to the particular exclusion in operation.

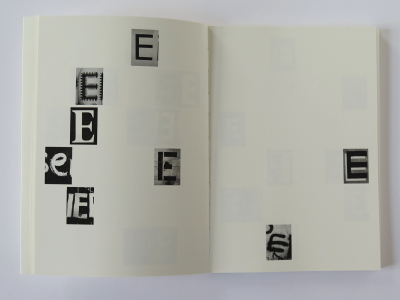

Over the next three centuries, there would be a handful of other lipogrammatic novels, of which Georges Perec's La Disparition (1969) ��� A Void in Gilbert Adair's English translation ��� is the best-known and most dazzling. A full-length detective novel, witty, self-referential, surprisingly moving, it eschews the letter e, the most common vowel in French as it is in English. Displaying a natural sense of balance, Perec followed this up with Les Revenentes, a novella in which e is the only vowel allowed, and a, i, o and u are avoided. Translated by Ian Monk as The Exeter Text, it recasts a family myth of how a trove of jewels, intended to fund the family's flight from the Nazis, was stolen at an orgy.

I was reminded of Perec's e-only text when I came across a pair of photography books which came out earlier this year: Joachim Schmid's E-Book and its companion, Joachim Schmid Works by Elisabeth Tonnard. Like Les Revenentes, Schmid's book uses only the letter e, only here it is not merely the only vowel, but the only letter whatsoever. The back cover informs us that the book's text is that of a letter which Schmid sent to Tonnard (the two artists are a couple), but redacted of everything but its es. Each e in the original, however, has been replaced with a photograph of that letter taken during Schmid's travels. Hundreds and hundreds of them: the es of public writing ��� bus stations, graffiti, shop signage, Ezra Pound's grave in Venice ��� a mosaic of found texts, each in its most minimal form and utterly different from the others.

Tonnard's book meanwhile consists of photographs of Schmid caught in the act of photographing these es, standing in the street, bent over manhole covers or straining to get a close-up of an awning. This is a book of unselfies: instead of a photograph of oneself taking a photograph of oneself, each of Tonnard's images is a photo of someone else photographing something else.

Playful and plural in their different ways but each unquestionably dedicated to the other artist, taken together these books are quite charming. Schmid cites Perec as an influence, and certainly Perec is now an unavoidable point of reference for vowel-play of this kind. But in this pair of works, replaying the original love letter as a love of the letter, and created as a side-project as the two artists sold their work at the small bookfairs of Europe and beyond, it is tempting to think that the courtly Alonso de Alcal�� y Herrera, poet and trader, might also have approved.

July 22, 2016

Dem bones

"The Two Princes Edward and Richard in the Tower, 1483" by Sir John Everett Millais, 1878

By DAVID HORSPOOL

Among the many mysteries about the disappearance of the "Princes in the Tower" in or around 1484 is that they turned up again. Well, their remains did, in 1674, dug up by workers at the Tower of London and reinterred four years later, with the permission of Charles II, in Westminster Abbey, where their urn can be seen to this day. The mystery in this case is not that quite a few people doubt that these bones were those of the princes (Edward V and his younger brother, Richard Duke of York), but that so few people seem aware of the discovery at all. Perhaps that is because, unlike the man who is still widely believed to have ordered their murder, Richard III, their remains were reinterred with very little fuss.

Now, the man who began the process of genetic and historical detective work that eventually led to the rediscovery of Richard's penultimate resting place, Dr John Ashdown-Hill, has claimed that the bones in the urn "show no relationship to Richard III". Dental analysis of the bones carried out in the 1980s (from photographs taken when they were inspected in the 1930s) showed that both had congenitally missing teeth, whereas new analysis of Richard's teeth shows no such defect. Because this "hypodontia" is relatively rare, it has previously been calculated that (to quote the article by Theya Molleson from 1987), "a relative is eight times as likely also to have hypodontia as the general population; that is, at least one in three relatives also has hypodontia". If you've followed me this far, you may have noticed that the "proof" is therefore of the absence of evidence rather than evidence of absence type. That is, Richard had a full set of gnashers, the children's remains didn't, so chances are they weren't related. Of course, they could have been, as two out of three relatives statistically don't share hypodontia.

In fairness to Dr Ashdown-Hill, the press release about the new edition of his book (on Edward IV's putative secret wife, Eleanor Talbot) probably overstates his own position, in the ordinary way of publicity machines. The real frustration for any researcher is that Westminster Abbey (and the Queen) have not been inclined to give permission for the urn's contents to be re-examined under modern conditions. But even if they were, what could really be established? If there was DNA available, perhaps their identity, but almost certainly not how they died, and very certainly not at whose hand. This, then, is the ultimate frustration for "Ricardian" defenders of Richard III's reputation, despite the extraordinary discovery of his bones in Leicester: they really can't answer the questions everyone asks about the king. Did he do it? Historians have tended to agree that he did, but the truth is, nobody knows, or is likely to ��� and that doesn't make for very good headlines.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers