The Man Booker ��� a TLS longlist

By TOBY LICHTIG

There is always a disjunction, when it comes to literary prizes, between the parameters adhered to by the judges and those demanded by the audience ��� not least for a prize as open to interpretation as the Man Booker.

The task of the panel is simple: to select what its members agree to be ���the best��� English-language novels to have been published in the UK over the past year. But what we, the public, tend to clamour for is something closer to a cross-section. When it comes to a long list, we demand balance, a range of different voices, themes and settings; of different nationalities and genres. Conversely, we also like to spot patterns and trends (a terrible journalistic habit). And of course we���re all hopelessly partisan about our own choices. Who has ever seen a longlist, or a shortlist for that matter, and genuinely thought: yes, those are exactly the ones I would have chosen?

When it comes to the Man Booker I���m firmly with Julian Barnes on the ���posh bingo��� front. As I discussed last night on Front Row with Alex Clark and John Wilson, this year���s is a particularly surprising list, blindsiding the critics with several novels that have barely been reviewed in the British press. Having not seen all 155 submitted books ��� and having, frankly, not read many of the ones on the current list ��� it would be unfair of me to criticize the choices. But while many of the entries are no doubt worthy of recognition, I could quite imagine an alternative reality in which all of these thirteen were replaced by thirteen deserving others. And certainly the list as a whole looks a little narrow to me. Everyone on it is either North American or British, with the exception of J. M. Coetzee, who represents the whole of Africa and Australasia. There are no Irish writers and no Asian ones (Madeleine Thien is a Canadian of Chinese parentage). There are fewer doorstops this year than in previous ones, and fewer sweeping narratives, with an emphasis on the family, the domestic.

So in the spirit of both inclusiveness and partisanship, I���ve decided to jot down a little selection of my own thirteen ���top��� novels from the past year. Of the Man Booker longlist, I���ve included three: David Szalay���s All That Man Is, Paul Beatty���s The Sellout and Madeleine Thien���s Do Not Say We Have Nothing ��� all excellent choices in my opinion. I haven���t yet received proofs of the new J. M. Coetzee novel, The Childhood of Jesus, and so I can���t in all good faith include this; but I have chosen, as a replacement, a novel by another author resident in Australia, Jack Cox. Unlike the Man Booker panel I���ve managed to include a couple of Irish novelists, as well as one at least partially representing Asia (Aravind Adiga, who was born in Madras and grew up in Australia). The Edna O���Brien inclusion is a bit of a cheat, as it���s technically a collection of linked stories ��� but then so too is David Szalay���s book, which was deemed kosher by the judges. And I���ve tried to include a little bit more experimental writing than did this year���s committee, in the forms of John Keene and Eimear McBride, as well as Cox.

All of these books have, naturally, been reviewed in the TLS, except for the ones that haven���t yet come out (or have only just come out) and are set to be reviewed over the coming weeks. And so, in alphabetical order, here there are:

-- Aravind Adiga���s Selection Day: Adiga is one of four debut novelists to have won the prize (for The White Tiger in 2008), which seems to be something of a death knell for literary careers. Neither Keri Hulme (The Bone People, 1985) nor Arundhati Roy (The God of Small Things, 1997) have published another novel since winning. D. B. C. Pierre (Vernon God Little, 2003) has, but his novels have not been especially well-received, and Adiga himself has struggled to achieve the recognition of his debut with his two subsequent books. But Adiga's new novel, out in early September, looks excellent ��� and our reviewer has already written to me to say how much he is enjoying it. Selection Day is set in contemporary Mumbai and features a fourteen-year-old boy struggling to come of age in a domineering and cricket-obsessed family.

-- Paul Beatty's The Sellout: I thought this was an excellent choice by the Man Booker panel. Beatty's satire on race relations in America, featuring an African American protagonist called "Me" who attempts to reinstate slavery and segregation in "agrarian" Los Angeles, is both hilariously funny and entirely on-the-button. Our reviewer, Bill Broun, called it both "inspiring" and, crucially, "much more than 'scathing' ��� it is constructive". And how's this for a funny takedown of black literary stereotypes?: "I'm so fucking tired of black women always being described by their skin tones! Honey-colored this! Dark-chocolate that! My paternal grandmother was mocha-tinged, caf��-au-lait, grahamfucking-cracker brown! How come they never describe white characters in relation to foodstuff and hot liquids?

-- Jack Cox's Dodge Rose: Wildly inventive, hugely tricksy and excellent fun all round, Cox's novel gets my vote for its ability to stretch language and test the reader. The novel is split into two sections, one featuring a young woman growing up in 1920s Sydney, the other focused on the woman's heirs, as they pick through her vast inventory of belongings some sixty years later. Paul Griffiths will be reviewing it in the TLS next month. He calls it: "Brilliant and dark, mysterious and immediate, moving and maddening, disturbing and entertaining . . . [an] extraordinary first novel that compacts the histories of a continent and of a family into a dazzle of two hundred pages."

-- John Keene's Counternarratives: Our reviewer Kate Webb was hugely impressed by this dazzling retelling of colonial history in the Americas, a "writing back" inspired by writers from Jean Rhys to Edward Said but achieved with an unique vision that is all the author's own. "We have", wrote Webb, "become accustomed in recent years to the revisionary spirit of much postcolonial fiction, but the ambition, erudition and epic sweep of John Keene���s remarkable new collection of stories, travelling from the beginnings of modernity to modernism, place it in a class of its own.

-- James Kelman's Dirt Road: The 1994 Booker winner's most recent novels features a father and son who go to America in response to a double bereavement, which transmutes, for the teenage boy, into an anxious, illicit road trip into adulthood. Sarah Crown will be reviewing the book in a future edition of the TLS and she is hugely impressed, calling it a "brilliant" and "universal" book: "quietly, subtly Kelman peels back the veil of daily life to reveal the urgent struggle of a sixteen-year-old coming to terms with death".

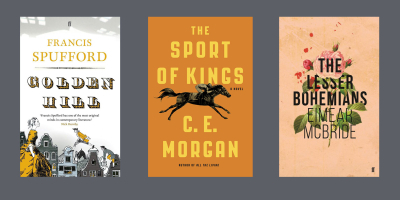

-- Eimear McBride' s The Lesser Bohemians: The exclusion of this novel from the 2016 Man Booker is, to my mind, the biggest miss of the lot and a crime to literature. Eimear McBride's brilliant follow-up to A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing, concerns a torrid love affair between an undergraduate drama student and an actor twice her age. It is sexy, urgent, moving, linguistically dazzling and filled with dramatic turns. The TLS will be featuring an exclusive extract from the book next month, and we will be reviewing it when it is published in September.

-- C. E. Morgan's The Sport of Kings: Somewhat oddly, two American "equestrian" books could easily have made the Man Booker longlist this year. Mary Gaitskill's The Mare was reviewed by D. J. Taylor in last week's TLS, and enjoyed by him for its wry, rueful treatment of American middle-class guilt; but it was Morgan's novel from earlier in the year that really sparked this paper's interest. Michael LaPointe noticed a new trend of American female authors producing "long, sprawling, ambitious novels" and concluded that Morgan had triumphantly joined their ranks with this "constantly invigorating, surprising and transfixing novel" about the scion of a farming dynasty who wishes to transform his family's corn fields into a breeding ground for race horses.

-- Sarah Moss's The Tidal Zone: It is hard to say, exactly, what makes Sarah Moss so special. She doesn't do anything particularly showy. Her settings are fairly small canvas. Not that much tends to happen ��� even when Moss moves her action between centuries, or sets her narratives in Greenland. She's just a very very good writer, and her latest novel, The Tidal Zone, in which an anxious father tends to his teenage daughter after she suffers an idiopathic cardiac arrest, is perhaps her best to date. Set against a backdrop of austerity Britain it entwines the father's anxieties with those of the wider nation. Our reviewer, Jonathan Gibbs, found great pleasure in the novel's "studied contemporaneity": "Moss, you feel, sees clearly where we are just now".

-- Edna O���Brien's The Little Red Chairs: Yes, it's technically a collection of interlinked short stories but, frankly, so is David Szalay's All That Man Is (see below) so I'm including it. O'Brien's book moves between Ireland and the Balkans, in what Lindsay Duguid described as "a compelling portrait of a world fractured by guilt and sorrow . . . . The narrative moves swiftly between the past and present tense, first person and third, in short sections and long chapters, mixing vague dreams and vivid memories with sharp scene-setting and close-up enactions of horror."

-- Annie Proulx's The Barkskins: We needed a least one doorstopping behemoth in the list, and what better one to choose than Proulx's epic take on loggers and conservationists set across Canada, the US, China and New Zealand. Our very own Editor Stig Abell praised Proulx���s use of metaphor, her lack of sentimentality and, above, the boldness of her vision: "Proulx has written a huge and brilliant novel, which takes us back to the uncompromising splendour of the natural world, and affirms her reputation as one of the greatest and toughest prose stylists writing today."

-- Francis Spufford's Golden Hill: The Man Booker long list is light on older historical novels (a bit of nineteenth-century whaling aside) and so I thought Spufford's entertaining book deserved a shot. A picaresque tale of an Englishman's misadventure in eighteenth-century Manhattan, it draws on Sterne, Smollett and the Fieldings (Henry and Sarah), and is written in the rhythms and diction of its setting's era. "Spufford���s exuberance and erudition are a wonderful combination", wrote Norma Clarke in the TLS. "The narrative never flags and nor does the sense that we are in several worlds at once, parlours with young women and prison cells with mad drunks that we have encountered in novels and films, rooftop escapes that defy credibility, a bonfire night crowd that turns ugly, bent judges, anxious traders, a coffee-house waiter who can respond to orders in at least five languages."

-- David Szalay's All That Man Is: I love this novel, even if it isn't a novel at all. Szalay's collection of nine interlinked stories, each featuring a different man facing a crisis at a different stage of life, zings with wry observations and coheres into a fascinating portrait of troubled (and pusillanimous) masculinity. The stories "are cleverly arranged", wrote Sam Jordison in the TLS, "running from spring to winter, full of ruses and subtle references to each other, to the different stages of life, to growing and waning, to naivety and experience." I was delighted to see this on the long list.

-- Madeleine Thien's: Do Not Say We Have Nothing: Another good choice by the Man Booker panel. Thien's novel concerns a woman who has fled to Canada in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square protests. Looking back on her past, she reflects on the Cultural Revolution and the lives of three musicians caught up in it. It will be reviewed in a future edition of the TLS.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers