Peter Stothard's Blog, page 11

March 8, 2016

Wilde child

By MICHAEL CAINES

"What do you say to a simple inscription", Oscar Wilde wrote to a friend on December 7, 1886:

To the Memory

of

Thomas Chatterton

One of England's greatest poets and sometime pupil at this school

The plan for a memorial tablet to Chatterton on the fa��ade of his old school, Colston's in Bristol, came to nothing. Wilde and his friend Herbert Horne were not alone, however, in their admiration, as Wilde went on to show: "I was very nearly coming to fetch you the night of the fog to come and hear my lecture on Chatterton at the Birkbeck, but did not like to take you out on such a dreadful night. To my amazement I found 800 people there! And they seemed really interested in the marvellous boy". . . .

That last phrase, too, indicates something of the Romantic history of the Chatterton cult, since it is Wordsworth's (and you can hear it in the course of the latest episode of TLS Voices, embedded below). His other admirers included Keats, Coleridge and Southey (who co-edited his poems). Today there is a modern Thomas Chatterton Society, established in 2002, on the 250th anniversary of his birth; most unusually for a literary society, and with the poet's sorry fate in mind, one of its aims is to "highlight the needs of teenagers like Chatterton in modern society".

You can see from modern anthologies, on the other hand, that few still think that Chatterton is one of "England's greatest poets", as Wilde apparently did. Perhaps it doesn't help that the most notorious productions of this eighteenth-century teenager are those he attributed to a fifteenth-century priest called Thomas Rowley. Here is an eighteenth-century teenager doing an impression of a fifteenth-century priest translating a poem by an eleventh-century monk about the only eleventh-century event that would happen to mean anything to an eighteenth-century readership:

Kynge Harrolde turnynge to hys leegemen spake;

My merrie men, be not caste downe in mynde;

Your onlie lode for aye to mar or make,

Before yon sunne has donde his welke, you'll fynde.

Your lovyng wife, who erst dyd rid the londe

Of Lurdanes, and the treasure that you han,

Wylle falle into the Normanne robber's honde,

Unlesse with honde and harte you plaie the manne.

Cheer up youre hartes, chase sorrowe farre awaie,

Godde and Seyncte Cuthbert be the worde to daie.

(Is there also a hint of Shakespeare's King Henry V before the Battle of Agincourt at the end there?)

Of these medieval fantasies, supposedly discovered amid the lumber of St Mary Redcliffe Church in Bristol, with which Chatterton's family had long been associated, only one was published in his lifetime, "Elinoure and Juga":

Systers in sorrorwe, on thys daise-ey'd banke,

Where melancholych broode, we wyll lamente;

Be wette wythe mornynge dewe and evene danke;

Lyche levynde okes in eche the odher bente,

Or lyche forlettenn halles of merriemente,

Whose gastlie mitches holde the traine of fryghte,

Where lethale ravens bark, and owlets wake the nyghte.

(The quainte spellynges aside, you can see here, I think, why Chatterton thought his sentimental and Gothic forgeries might appeal to Horace Walpole, who had himself perpetrated a literary fraud in the form of The Castle of Otranto, supposedly translated from an Italian original and "found in the library of an ancient Catholic family in the north of England".)

Not many of the wiser sort were convinced of the authenticity of the Rowley poems, although a campaign of support was to outlive Chatterton himself, who died at the age of seventeen in 1770 (or killed himself, the mythologizers preferred to believe).

In turn, Wilde's admirers will know what that alarming word "authenticity" meant to him ��� this is the man who declared that "art's aim", in The Picture of Dorian Gray, is to "reveal art and conceal the artist". And that "One should always be a little improbable". And: "The first duty in life is to be as artificial as possible. What the second duty is no one has as yet discovered". A poet who seems to have lived by these maxims was bound to appeal to the aphoristic Oscar, as Nick Groom shows this recently published TLS review.

That makings of that lecture about Chatterton survive as a notebook that has caused some controversy: Professor Groom tells how some took its contents as evidence that Wilde was a plagiarist. Instead, we might now say, the notebook shows how Wilde was deeply interested in the marvellous boy. It helps us to see why he believed Chatterton deserved that memorial in his home town ��� and why he "remained a touchstone" in Wilde's work.

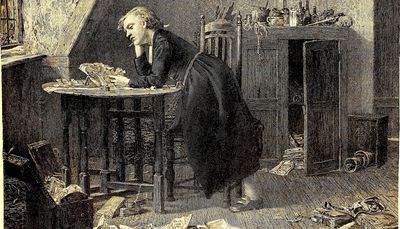

There may be a hint of him, for example, in the figure of the garret-bound writer in "The Happy Prince", for whom the prince has one of his own sapphire eyes plucked out. "I am beginning to be appreciated", the poor writer observes, on receipt of this gift. "'This is from some great admirer. Now I can finish my play', and he looked quite happy." It's not the only possible reading of that passage, but I like the idea of Wilde reversing what he called "the most tremendous tragedy in history" by way of this children's story. Chatterton himself would no doubt have loved the idea, and tried to put it into oldde englysshe.

Wilde at heart

By MICHAEL CAINES

"What do you say to a simple inscription", Oscar Wilde wrote to a friend on December 7, 1886:

To the Memory

of

Thomas Chatterton

One of England's greatest poets and sometime pupil at this school

The plan for a memorial tablet to Chatterton on the fa��ade of his old school, Colston's in Bristol, came to nothing. Wilde and his friend Herbert Horne were not alone, however, in their admiration, as Wilde went on to show: "I was very nearly coming to fetch you the night of the fog to come and hear my lecture on Chatterton at the Birkbeck, but did not like to take you out on such a dreadful night. To my amazement I found 800 people there! And they seemed really interested in the marvellous boy". . . .

That last phrase, too, indicates something of the Romantic history of the Chatterton cult, since it is Wordsworth's (and you can hear it in the course of the latest episode of TLS Voices, embedded below). His other admirers included Keats, Coleridge and Southey (who co-edited his poems). Today there is a modern Thomas Chatterton Society, established in 2002, on the 250th anniversary of his birth; most unusually for a literary society, and with the poet's sorry fate in mind, one of its aims is to "highlight the needs of teenagers like Chatterton in modern society".

You can see from modern anthologies, on the other hand, that few still think that Chatterton is one of "England's greatest poets", as Wilde apparently did. Perhaps it doesn't help that the most notorious productions of this eighteenth-century teenager are those he attributed to a fifteenth-century priest called Thomas Rowley. Here is an eighteenth-century teenager doing an impression of a fifteenth-century priest translating a poem by an eleventh-century monk about the only eleventh-century event that would happen to mean anything to an eighteenth-century readership:

Kynge Harrolde turnynge to hys leegemen spake;

My merrie men, be not caste downe in mynde;

Your onlie lode for aye to mar or make,

Before yon sunne has donde his welke, you'll fynde.

Your lovyng wife, who erst dyd rid the londe

Of Lurdanes, and the treasure that you han,

Wylle falle into the Normanne robber's honde,

Unlesse with honde and harte you plaie the manne.

Cheer up youre hartes, chase sorrowe farre awaie,

Godde and Seyncte Cuthbert be the worde to daie.

(Is there also a hint of Shakespeare's King Henry V before the Battle of Agincourt at the end there?)

Of these medieval fantasies, supposedly discovered amid the lumber of St Mary Redcliffe Church in Bristol, with which Chatterton's family had long been associated, only one was published in his lifetime, "Elinoure and Juga":

Systers in sorrorwe, on thys daise-ey'd banke,

Where melancholych broode, we wyll lamente;

Be wette wythe mornynge dewe and evene danke;

Lyche levynde okes in eche the odher bente,

Or lyche forlettenn halles of merriemente,

Whose gastlie mitches holde the traine of fryghte,

Where lethale ravens bark, and owlets wake the nyghte.

(The quainte spellynges aside, you can see here, I think, why Chatterton thought his sentimental and Gothic forgeries might appeal to Horace Walpole, who had himself perpetrated a literary fraud in the form of The Castle of Otranto, supposedly translated from an Italian original and "found in the library of an ancient Catholic family in the north of England".)

Not many of the wiser sort were convinced of the authenticity of the Rowley poems, although a campaign of support was to outlive Chatterton himself, who died at the age of seventeen in 1770 (or killed himself, the mythologizers preferred to believe).

In turn, Wilde's admirers will know what that alarming word "authenticity" meant to him ��� this is the man who declared that "art's aim", in The Picture of Dorian Gray, is to "reveal art and conceal the artist". And that "One should always be a little improbable". And: "The first duty in life is to be as artificial as possible. What the second duty is no one has as yet discovered". A poet who seems to have lived by these maxims was bound to appeal to the aphoristic Oscar, as Nick Groom shows this recently published TLS review.

That makings of that lecture about Chatterton survive as a notebook that has caused some controversy: Professor Groom tells how some took its contents as evidence that Wilde was a plagiarist. Instead, we might now say, the notebook shows how Wilde was deeply interested in the marvellous boy. It helps us to see why he believed Chatterton deserved that memorial in his home town ��� and why he "remained a touchstone" in Wilde's work.

There may be a hint of him, for example, in the figure of the garret-bound writer in "The Happy Prince", for whom the prince has one of his own sapphire eyes plucked out. "I am beginning to be appreciated", the poor writer observes, on receipt of this gift. "'This is from some great admirer. Now I can finish my play', and he looked quite happy." It's not the only possible reading of that passage, but I like the idea of Wilde reversing what he called "the most tremendous tragedy in history" by way of this children's story. Chatterton himself would no doubt have loved the idea, and tried to put it into oldde englysshe.

March 4, 2016

A Russian in the Acad��mie

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

The writer Andre�� Makine (above) has just been elected to the Acad��mie fran��aise. Born in the former Soviet Union in 1957, where his grandmother instilled in him a love of the French language, Makine travelled to France in 1987 on a teacher���s exchange programme and decided to stay. He was subsequently granted political asylum in the country.

A mere eight years after settling in France, Makine won the Prix Goncourt with his lyrical fourth novel Le Testament fran��ais ��� a book that was firmly rooted in the author���s Siberian childhood and adolescence. A prolific author, he has published some ten novels since (all of them translated into English by Geoffrey Strachan).

The main function of the Acad��mie, which was founded by Cardinal Richelieu in 1635, is to act as guardian of the French language. It was recently embroiled in the controversy over reforms to French spelling.

Makine is the fifth writer of Russian origin to be elected to the august body, after Henri Troyat, Joseph Kessel, Maurice Druon and the historian of Russia H��l��ne Carr��re d���Encausse, who is its permanent secretary. He will be taking the seat (or fauteuil) vacated by the Algerian novelist Assia Djebar, who died last year. In doing so he joins the ranks of forty immortels. His most immediate predecessor is the Haitian writer Dany Laferri��re, who was elected in 2013. (The Acad��mie also boasts a British member, Michael Edwards.)

From Soviet defection to the Prix Goncourt and now the Acad��mie fran��aise in less than thirty years. It���s an impressive trajectory.

March 3, 2016

The Jamesian scene

Henry James, c.1910. Photo: �� Corbis

By MICHAEL CAINES

It is a century, anyone might say in that hazily accurate way, since the death of Henry James, but today, Thursday March 3, 2016, we may say in confidence of expressing ourselves with exactitude, a whole century since the funeral of the Master took place, on March 3, 1916, at Chelsea Old Church. (I have been reading The Sacred Fount, so apologies for the inept but, I assure you, involuntary essay in pastiche.) This afternoon, indeed, almost to the hour, that sombre occasion is to be commemorated at the same blessed venue that was formerly, in the words of Professor Philip Horne ��� who writes poignantly in this week's TLS of James's final illness and the funeral itself ��� "Sir Thomas More's private chapel". The author's friends had "lobbied" for Westminster Abbey, but the family took a "more dignified" line. Amid the distinguished congregation, one mourner, Rudyard Kipling, could describe the funeral as "the most touchingly beautiful service I have ever heard" . . . .

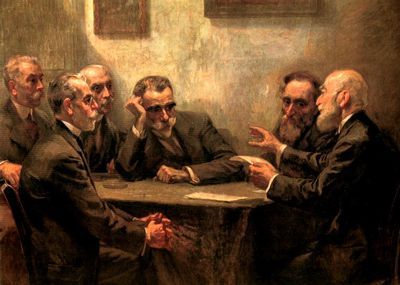

James contributed to the TLS on a few occasions; and it's strange to think of him writing on, say, Balzac anonymously, as the paper then demanded, yet in that irremediably distinctive way. As far as the more discerning sort of reader was concerned, it was perhaps possible to make out the identity of the author. TLS readers had indeed, since the first year of the paper's publication, been treated to regular updates on James's latest works ��� from The Wings of the Dove onwards, and courtesy of reviewers such as Walter de la Mare and the Jamesian expert Percy Lubbock ��� and the peculiar nature of their appeal, the exquisite uncompromised splendour of their Art. (I have a soft spot, though, for Thom Gunn's "Jamesian", which reduces the whole business to two lines: "Their relationship consisted / Of discussing if it existed".) And there was a debate already well under way concerning the early, middle and late periods, which was thus brought into an imaginary salon or debating chamber after James's death in a review of The Ivory Tower (a novel he didn't live to finish):

"There are generally three parties or factions present: the larger group, which praises all the bright array of cultivated, lucid, readable novels and stories written in his earlier period, Daisy Miller, Roderick Hudson and the rest. A smaller and more select faction expresses appreciation also of the books of the middle time. But both groups combine to deplore what they consider the sad falling-off of his last period; the disintegration, as they think it, of his style, and the general lapse into difficulty and diffuseness which makes, they declare, books like The Awkward Age, The Ambassadors and The Golden Bowl practically unreadable. And then, solitary among them but undismayed, the enthusiast takes up the theme, maintaining that it is precisely in these works, and only in these, that Henry James's genius found complete expression ��� an expression so new, so original, so personal, so surprising that by comparison his earlier works all sink into insignificance."

There has been much else to debate since those times, of course, although in the face of this question about James's artistic development I now recall that a Jamesian enthusiast possibly of the last stripe would kindly recommend Daisy Miller as a more appropriate starting point for the uninitiated than, say, The Ambassadors. (Does anybody strongly support alternative suggestions?) That later work prompted the TLS's reviewer to write: "Mr James demands unswerving and intense attention from his readers. Skip half a page and the next page or two are at once reduced to gibberish".

By contrast, I would say, if you don't read anything else today at all, skip to the final paragraph of "Refugees in Chelsea", an essay by James published in the TLS shortly after his death ��� all you may need to know in advance, I hazard, by way of context, is that he had "flung himself into the war effort", as Professor Horne writes, "caring for Belgian refugees, visiting wounded soldiers, serving as honorary president of the American Volunteer Motor Ambulance Corps". It was a cause he cared deeply about ��� as that last paragraph alone is enough to demonstrate ��� deeply enough, indeed, for him to adopt British citizenship in the summer of 1915. And as Horne goes on to suggest, the strain did not do the old man any good ��� crass though the thought may be, it is not entirely implausible to think of Henry James as yet another victim of the First World War, albeit one whose death took place not in No Man's Land but in Chelsea.

March 2, 2016

Log-rolling for beginners

Parnassos Literary Society by Georgios Roilos

By MICHAEL CAINES

Of course, some say, it's unavoidable: the world of, say, Liminal Gnocchi studies is small, and when one of the grands fromages of LG studs publishes a major work of scholarship, it's impossible to find a reviewer who doesn't already know Professor Al Dente personally. Indeed, your reviewer is in Dente's "acknowledgements", listed as "a close personal friend whom I've known for years, and whose comments on the manuscript to this book have proved invaluable". But never mind ��� a review's a review.

The Gnocchi scenario aside, however, I doubt that all readers are aware how shamelessly, craftily and unrelentingly writers seek to review one another. I wouldn't say it's a daily or even a weekly event that I receive such a request, typically from a reviewer new to me. It happens often enough, though, that I receive an e-mail along these lines: do I need somebody to cover so-and-so's excellent new book? It's not published until October, but the would-be critic happens to have read it in draft. . . .

In other words, don't be surprised that friends wish to help friends, albeit in this small way ��� that's what friends do, right? But perhaps I'm allowed to raise an eyebrow, even after taking years trying to reconcile myself to the phenomenon, that friends do it so flagrantly.

Sometimes such proposals arise from naivety. There's a young chap gadding around other people's book pages, I know, who first asked me if he could review a novel he'd seen in manuscript, exactly as described above. More recently, we were approached by a biographer who wanted to do his fellow biographer a good turn, absolutely untroubled by the fact that he's never strayed into her historical period before ��� and also that they were well known to be thieving-thick.

Mere gossip, you'll say, unhelpfully shorn of the proper names. A couple of exceptional cases. It's also ��� to revisit the Gnocchi scenario for a moment ��� a different matter when you know that somebody serious-minded and at work in the same field wants to re-engage with the latest production of a contemporary. Even the timorous editor can then feel that they might just be furthering some worthwhile intellectual dialogue.

(An extreme example: there was a spat in the letters page among historians of Madagascar a few years ago; but as one of the correspondents claimed, "there are only three of us", condemned to spend their careers reviewing one another.)

When the subject came up recently in conversation at TLS HQ, however, it turned out everybody present could name more than one instance of sheer unabashed log-rolling; and it's the unabashed tone that particularly intrigues me. The academic who offered to review a book by his sometimes co-author; the well-meaning enthusiast who wanted to review the latest collection of stories by a Danish author, after (he declared with understandable pride) spending a few days with her and, yes, reading the manuscript in advance.

Is this in part an academics' attitude problem (career advancement hinging on such alliances) or is it more the fault of the books pages fostering the impression that disinterested opinion is worth less to them than enthusiastic back-scratching? When confronted with certain my-back-your-back instances of poetry reviewing, for example, you might well think so. In the course of that recent chat, somebody recalled a review of an essay collection, in which singled out for praise was a contribution that turned out to be by the reviewer's wife.

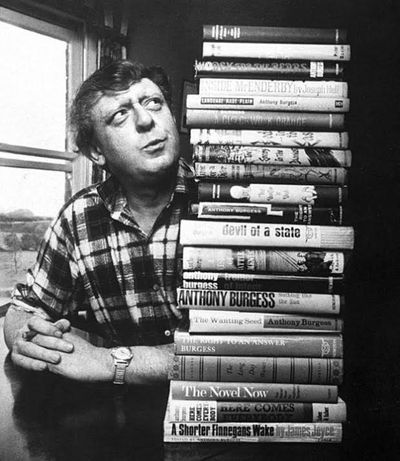

It's sometimes said that what the book reviewers say doesn't matter much in commercial terms. If that's the case, it certainly doesn't stop some authors from caring deeply about who gets to say what about them in print. I suppose it partly depends how puritanically you regard reviewing as a critical activity set apart from (apart from, and maybe below, please note, but most certainly not above) the book industry as a whole. Crossing the line isn't necessarily a bad thing, at least in the longer term: it's still of interest, I would guess, to Inklings aficionados, to know what C. S. Lewis could get away with saying about J. R. R. Tolkien (anonymously) in 1937 ��� or for anybody to take heart from Walter Scott's harsh review of his own work and Anthony Burgess's account of Inside Mr Enderby by "Joseph Kell". "This is, in many ways, a dirty book", Burgess wrote of what was, in fact, a work of his own. "The book itself is a laughing-stock. And yet how thin and under-savoury everything seems after Enderby's gross richness."

If anybody's managed to get away with that one recently, I'd love to know. In the meantime, it's one reason for us to go on, as we generally do, commissioning reviews after seeing the books for ourselves rather than, as some papers nonchalantly do, trusting to taking reviews on spec.

March 1, 2016

Rewarding arts journalism

Anthony Burgess; photo from the International Anthony Burgess Foundation collection

By RUTH SCURR

Reviewers are rarely rewarded with prizes. Our craft is to write persuasively about the aspirations and achievements of others. But at its best reviewing can be an art form too. The annual Observer/Anthony Burgess Prize for Arts Journalism is awarded to an unpublished 1,500-word review of a recent book, film, concert, exhibition, ballet, play, TV show or performance art piece.

I was delighted to be a judge on the 2015 panel, alongside the writers Alexandra Harris, Kate Mosse, Robert McCrum and Will Carr (the Deputy Director of the International Anthony Burgess Foundation).

Last Thursday we presented the prize to Leah Broad, a graduate student, for her review of a performance of Sibelius���s songs, which has now been published in the Observer. We also chose two runners-up: Ed Cripps for his review of the South Bank Show���s interview with Paul Greengrass, and Iris Veysey for her review of an exhibition of Candida H��ffer���s photographs.

We selected the winners from an extremely strong and diverse shortlist, that included a review of the Wellcome Trust���s sexology exhibition (by Scott Wilson), a review of John Gray���s A Short Enquiry into Human Freedom (by Tom Startup), a review of Blur���s Winter Garden concert (by Madeline Pettit), and a review of the crime comedy film Inherent Vice (by Tom Evans).

Observer / Anthony Burgess Prize for Arts Journalism winner, Leah Broad. Photo: Sophia Evans for the Observer

Observer / Anthony Burgess Prize for Arts Journalism shortlisted writers (left to right): Leah Broad, Iris Veysey, Madeleine Pettit, Ed Cripps, Tom Startup, Tom Evans, Scott Wilson. Photo: Sophia Evans for the Observer

How did we do it? During the judging process the entries were anonymous, so the gender and provenance of the authors were irrelevant. We did not agree on any specific criteria for deciding on ���the best��� reviews, but as we discussed each entry in turn, it became clear that we valued two qualities above all others.

The first was fine writing: nothing pompous or verbose. We weren���t looking for pastiche Burgess, but for new, vivid voices, as creative and articulate today as he was in his time. Burgess began reviewing when he was a student at Manchester University (1937���40) and never stopped. He wrote for the TLS as well as the Listener, the Spectator, the Guardian and the Observer. A selection of his literary essays, Urgent Copy, was published by Jonathan Cape in 1968, followed by the bulkier Homage to Qwert Yuiop in 1986.

The second quality we looked for was the ability to project a single example of an art form onto its wider cultural context. The best reviews deepen our understanding not just of one new book, film, performance etc., but of the whole genre into which it fits (however awkward or innovative that fit might be).

Last Thursday (February 25) would have been Burgess���s ninety-ninth birthday. The prize that carries his name goes from strength to strength, and the centenary celebrations are something to look forward to.

February 25, 2016

Drinking whisky with Umberto Eco

Umberto Eco, 2015; copyright Leonardo Cendamo/Writer Pictures

By IAN THOMSON

Umberto Eco, Italy���s best-known literary export, was in a bad way when I met him in 1986 at Bologna University, where he was Professor of Semiotics (that abstruse branch of literary theory). ���I���ve become a dissociated and schizophrenic personality���, he told me, crumpling up a cigarette packet. ���The movie of The Name of the Rose has upset my psychic balance!��� Shuffling grumpily round his office, he lifted up and slammed down books. Eco���s 1980 medieval whodunit had just been made into a film by the French director Jean-Jacques Annaud, starring Sean Connery as the monk-detective William of Baskerville. An artful reworking of Conan Doyle (with Sherlock Holmes transplanted to fourteenth-century Italy), the novel had sold more than 10 million copies worldwide. However, Eco refused to speak to journalists about the film.

Each night when he returned to his flat in Milan, he could ���hardly open the door��� for the accumulation of interview requests. In private, Eco judged Annaud���s movie a travesty, and found the monks (apart from the one played by Connery) ���simply far too grotesque-looking���. To top it all, Italian Vogue had claimed that Eco was writing a novel based on the life of Mozart. ���Not true! I feel blackmailed by journalists, by myself, by you, by my publisher. I don���t feel free any more. When I wrote The Name of the Rose it was half for fun ��� a free act. Now I ask myself: ���Am I writing a new book because I want to, or because it���s expected of me?������ In a voice made husky by sixty cigarettes a day, Eco grudgingly conceded that Annaud���s Piranesi-like sets were ���quite good���. In his trademark tweed deerstalker, Eco cut an odd figure.

The Name of The Rose: Sean Connery and Christian Slater, 1986

His death last week at the age of eighty-four provoked a deluge of obituaries. A polymath of towering cleverness who was fond of scholastic hair-splitting and arcane medieval erudition, Eco was not uniformly admired. His novels had the look and feel of encyclopedias, and combined cultural influences ranging from T. S. Eliot to the Charlie Brown comic strips. The success of The Name of the Rose weighed heavily on him. Joggers in Central Park listened to the novel on their Walkmans. Eco���s gifted English translator, William Weaver, built an extension on his Tuscan home with the proceeds: the Eco chamber, he called it. Eco���s second novel, Foucault���s Pendulum, published a couple of years after we met, in 1988, was a thriller set amid shadowy cabals and conventicles such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Eco saw modern-day political parallels with these and other sects; Italy���s crypto-fascist P2 masonic lodge and the far-left fringe of the Red Brigades indulged a similar secrecy and fanaticism. Not surprisingly, Eco liked to use the Italian term dietrologia, which translates, not very happily, into ���behindology��� and presumes that secret cliques and consortia are everywhere manipulating political scandals. In all his work, fiction and non-fiction, he displayed a quite Italian fascination for conspiracy and arcana.

���May I be permitted to offer you another whisky?���, he asked. I held out my glass and he accidentally stubbed out his cigarette in his own. ���Hell, I���m drunk!��� Bologna University had been a hotbed of Italian red activism in the 1960s and early 70s, and the philosophy faculty where we spoke was spray-gunned with political slogans and crude attempts at action painting. Eco was not that impressed. ���It was supposed to be a ���creativity equals liberty��� campaign, but the graffiti isn���t as witty as it used to be.��� Still Bologna is the undisputed gastro-heart of Italy, and Eco relished the city���s rich cuisine as well as its lewd medieval street names (via Fregatette, ���Rub-Tits Street���, was one of his favourites). Portly, with a great black beard, he gave lectures attended by semioticians of every stripe. Eco said he was definitely not ���intellectually slumming it��� by speaking of Donatello���s David in the same breath as, say, the US porn star and vice-presidential candidate Marilyn Chambers. When the entire world is a web of signs, he insisted, everything cries out for exegesis.

���Marginal manifestations of culture should not be ignored���, he went on, pouring us another shot of Talisker malt. ���In the nineteenth century, Telemann was considered a far greater composer than Bach; by the same token, in 200 years, Picasso may be thought inferior to the Coca Cola commercials.��� (And who knows, Eco added half-jokingly, one day we may consider The Name of the Rose inferior to the potboilers of Harold Robbins.) In his mandarin analysis of the mundane, Eco was influenced by the French counter-culture essayist Roland Barthes. While Barthes wrote about washing powder, Greta Garbo���s face, or the new model Citroen in a subtle, teasingly paradoxical prose, Eco���s essays (collected variously in Faith in Fakes, Travels in Hyperreality and How to Travel With a Salmon) showed a certain crude braggadocio and swagger. He was at his best when composing bookish parodies and spoof sequels to famous novels. In one of these, the narrator of Marcel Proust���s A la Recerche du temps perdu dies in Dublin after reading Joyce���s Ulysses and drinking an excess of Guinness.

Eco���s last novel, Numero Zero, published in 2015, was a razor-sharp thriller set in Milan in 1992, and deservedly a bestseller in Italy. Pape Sat��n Aleppe: Cronache di una societ�� liquida, a collection of essays that originally appeared in L'Espresso, will be published tomorrow.

A selection of articles written by Umberto Eco for the TLS from the 1960s onwards ��� "a blend of aphorism and didacticism", as J. C. describes them in the current issue ��� is available on the TLS website.

February 24, 2016

Religion in a test tube

Professor Jerry Coyne; photograph by Andrew West/ British Humanist Association

By MAREN MEINHARDT

Talking to a roomful of humanists about the superiority of science over religion is an activity apt to bring the words ���preaching��� and ���converted��� to mind ��� although preaching, of course, doesn���t really come into it.

The occasion was this year's Darwin Day Lecture ��� established by the British Humanist Association in 2003, after which it has been given, traditionally, on the Saturday nearest to Darwin���s birthday ��� the 2016 event fell squarely on the date itself, February 12. This year���s speaker was Professor Jerry Coyne, who has made significant contributions to our understanding of speciation, and whose review of Matt Ridley���s The Evolution of Everything appears in the current issue of the TLS. (His own book, Faith vs. Fact, was reviewed in the TLS of January 22, 2016.) The ���room��� in question was Logan Hall, a lecture theatre at the Institute of Education which holds almost 1,000 people, and the event had been sold out for weeks in advance.

Proving the superiority of science over religion may not seem, at first, so pressing an undertaking to a British audience, who have witnessed steadily declining church attendance over the years, and encounter churches, as often as anywhere else, on the property pages, where, increasingly redundant, they are advertised for sale.

Most people in Britain are aware that the situation in America is different, but the extent of the headway made by young earth creationism and ���intelligent design��� seems not to be fully appreciated. The Logan Hall audience, at least, seemed startled when confronted with the numbers. In the United States, Coyne reported, 40 per cent of people profess not to ���believe��� in evolution. On top of that, 55 per cent of them think that evolution, ���intelligent design��� and creationism should be allocated equal space in science lessons in school. The background to this is political, Coyne pointed out: in America, it is problematic to state that science and religion might be incompatible, he said, and academic funding can be conditional on adopting this position. Therefore, he explained, a popular strategy is to declare religion a separate entity, autonomous from other endeavours, and express sentiments of the ���you can���t put religion in a test tube��� variety. Coyne, predictably, had little truck with this: religious tenets can be subjected to scientific scrutiny, and should the efficacy of intercessory prayer be scientifically investigated, he'd be reasonably confident of the outcome.

Whether people believe in evolution is beside the point, Coyne said: belief is not something science has the need to resort to. While religion, he said, adduced facts, but lacked proof to support them, evolution, by contrast, was able to call on the support of many diverse fields of knowledge. Most of these (the fossil record; molecular biology; embryology) are abundantly familiar. But Professor Coyne was able to add to our understanding of vestigial organs ��� features of the body that are obsolete in a species but have been retained ��� by expertly wiggling his ears, using three muscles behind the ear whose use now is not entirely lost, but these days restricted mostly to illustrative purposes in support of evolutionary theory.

To those proposing a more conciliatory position, that religion and science should enter mutually constructive dialogue, Coyne had little to say that was of comfort: science and religion are indeed related, but not in a happy way. He had figures to show it. One graph plotted the negative correlation between religious belief and acceptance of evolution. Another demonstrated that belief in God was highly correlated with social dysfunction (defined by social markers such as teenage pregnancy, infant mortality, rates of incarceration, and the availability of health care). Of the countries included in the graph, the US, he pointed out, was represented by the dot on the far right on the x-axis: the most religious, the least socially successful.

For Coyne, the road to improving the understanding of science ��� and incidentally, to weakening religious belief, something he made no pretence of feeling sorry about ��� is pragmatic and straightforward: we need to promote social change, improve income equality and seek to establish universal healthcare.

���My quarrel���, said Coyne in answer to a question from the audience about new-age spirituality, ���is not with people believing crazy stuff, but with things that hurt humanity.���

February 23, 2016

Infinite Jest at 20

David Foster Wallace, 1996 �� Garry Hannabarger/Corbis

By ROBERT POTTS

David Foster Wallace's extraordinary 1000-page novel Infinite Jest is twenty years old this month. It was regarded as a classic almost on arrival, and the years have deepened and affirmed that status. It is significant that the TLS has returned to the novel on numerous occasions over the intervening period: as Thomas Meaney wrote, in 2013, "To be the distiller of the times for a generation is no small feat".

Bharat Tandon reviewed Infinite Jest when it was first published, in 1996. Despite the novel's density and complexity (the last 100 or so pages are end-notes which are sometimes highly illuminating, occasionally playfully unhelpful ��� "no clue" ��� and, on one occasion, completely blank), and its rambling, multi-styled sentences and paragraphs, Tandon identified most of the crucial features, including the link between a conspiracy theory culture and the reader's own acts of interpretation; the addictive nature of a book about addiction; and the debt to Thomas Pynchon. Tandon described Infinite Jest as "allegorical sci-fi, recasting and stylizing contemporary anxieties as the genre has always done", but concluded that it "never seems more than the sum of its weighty parts".

By the time of the tenth-anniversary reissue, Wallace's reputation had grown; he had not written another novel, but his short fiction and his essays showed a remarkable refinement of the themes and stylistic devices he had deployed in Infinite Jest. The game-playing could now be seen as intimately linked with philosophical, psychological and cultural anxieties; what seemed like heartless evasion was in fact a diligent manoeuvring around and towards some difficult and deeply heartfelt material. Stephen Burns, reviewing the reissued text, located the novel in its pre-millennial moment. He also picked up on the Joycean structure of the novel, in which the ostensible protagonist, Hal Incandenza, gradually descends into a Hamlet-like paralysis, while the unpromising figure of Don Gately, a drug-addict and criminal, steadily rises towards potential redemption: "Between the cynicism of youth and the developing sincerity of the recovering addict, Wallace attempts to explore what he calls 'the soul's core systems', probing his characters' sometimes nebulous sense of self". By now the incoherence Tandon had quite fairly criticized was mostly overlooked (barring some good quibbles about chronology) in favour of an admiration for the way in which the novel's overarching structure and (even at the level of a phrase or sentence) its diverse styles were a crucial part of its message.

Wallace hanged himself in 2008. The profusion of material that followed ��� previously unpublished manuscripts, criticism, memoirs, and so on ��� added new contexts; the addiction and self-consciousness that Wallace had presented as universal cultural and philosophical problems could be reduced to pathologies of the author himself. Paul Quinn's piece from last year deprecates the biographical turn in Wallace Studies. (Interestingly, none of our critics wondered whether one drive behind the writing of Infinite Jest might have been a testosterone-fuelled competitiveness ��� a boyish obsession with size and virility.) Wasn���t Infinite Jest also the capturing of a historical and cultural truth ��� what Quinn was able to call "Wallace's (and his generation's) defining work"?

The posthumous publication of the artfully assembled parts of Wallace's unfinished final novel, as The Pale King (2011), set in the 1980s in a rural department of the IRS, by sheer contrast further put Infinite Jest into its historical context. Quinn discusses Ralph Clare's claim that "Infinite Jest was the product of the 'Clintonian Golden Age' and 'the apparent fruition of neoliberal economics . . .' . The Pale King, on the other hand, was written 'during the exhaustion of the neoliberal promise', and 'returns to neoliberalism���s historical roots in the 1970s and its rise in the 1980s'". One might further note that as well as the economic crash, and the reassessment of value that followed, the events of 9/11 significantly reshaped aspects of the culture which Wallace had satirised in Infinite Jest. (The already comical terrorist subplot looks even more cartoonish in the light of twenty-first-century conflict.) Terrorism is treated with altogether more grimness in the short-story collection Oblivion (2004), albeit by Wallace's habitual use of suggestive tangents rather than direct engagement.

Twenty years on, Wallace's sprawling novel ��� a "battleship", an "encyclopedic behemoth", "gargantuan" ��� remains as powerful as ever. It had a profound influence on the novels that followed it, whether in imitation or conscious rejection. In style and intelligence it remains an unignorable challenge to readers and writers alike. But most importantly, beneath its brilliant stunts and set-pieces, it is a novel about sadness, about families, about the many barriers ��� psychological, socio-economic, technological, cultural, philosophical ��� between the self and others. It manages to be both hilarious and heart-breaking.

David Foster Wallace in the TLS:

The first review of Infinite Jest in the TLS: Bharat Tandon, 1996

Brief Interviews with Hideous Men: Lawrence Norfolk, 2000

On Oblivion: Stephen Burn, 2004

Consider the Lobster: Catherine Humble, 2007

The Pale King ��� "David Foster Wallace���s less-than-final text": Robert Potts, 2011

David Foster Wallace on Planet Trillaphon: Thomas Meaney, 2013

DFW reception: Paul Quinn, 2015

Boris versus Bunhill

By MICHAEL CAINES

What would a country run by Boris Johnson be like? Hilarious? No doubt. What japes there will be when this Shakespeare biographer is running the show. I wonder if he'll also be doing more of this, too: turning London into a giant office and effectively overruling a Grade I listing in the process . . . .

Just off the City Road, on the edge of the Square Mile, Bunhill Fields is a modest park (around the size of two football pitches) where office workers take some green respite from their desks. The City of London officially describes it as an "an oasis of calm and greenery in a busy, congested locality". Yet it has a past life, if that's the right word, as a burial ground for Nonconformists; 120,000 people were buried there, it is believed, including a handful of writers: William Blake, Daniel Defoe, John Bunyan and Isaac Watts, the "Father of English Hymnody".

You can add to that list the "Mother of Methodism" Susannah Wesley; Blake's wife and assistant Catherine; "Lady Lewson", said to be one model for Miss Havisham; the Quaker George Whitehead; and hundreds of Dissenting ministers and figures of interest, including antiquaries, brave Dissenting booksellers, inventors and radical politicians, to whom memorials also stand in the pages of the ODNB.

Robert Southey could justly call Bunhill "the Campo Santo of the Dissenters", and the significance of this historical community, who were given the status of inferior citizens by the Test and Corporation Acts of the 1660s, remains insufficiently acknowledged. As Timothy Larsen wrote in the TLS last year:

"The enormous influence once wielded by British Nonconformists is often downplayed today. . . . Nonconformist cultural contributions still surround us in names we routinely evoke: Cadbury���s, the YMCA, Thomas Cook, Aston Villa, Barclays, the Tate and much more. Full-blooded Dissenters would have said that their most important legacy was spiritual: they had produced the greatest preachers (C. H. Spurgeon), missionaries (David Livingstone) and social reformers (Elizabeth Fry)."

Understandably, if belatedly, this park-and-long-retired-cemetery received a Grade I listing in 2011, "putting it into the top 10% of the 106 listed cemeteries in England", while many monuments were also simultaneously given Grade II listings. The theory is that such a listing affords a measure of protection against "any form of development or interference".

Well, now we know how the Mayor of London views a Grade I listing. Developers have proposed erecting four blocks of offices that will overlook, overshadow and overwhelm the park; one of the towers to be ten and another eleven storeys high. Islington Council, the Ancient Monuments Society and the Blake Society have opposed the plans, saying they would cause "significant harm" to a garden of "special historic interest". ���The newcomer is just too vast", observes the AMS. "Part of the character of Bunhill is that sense of modern life crowding in but not spoiling it ��� its mood is the more rarefied precisely because of that tension.���

Johnson's decision? To call in the planning application and approve it on February 8 ��� the third time in three years he has overruled the local council in favour of developers.

Of course, there is nothing unusual or necessarily wrong about a new office block going up in London. (I'm writing these words from a relatively new one myself.) We need more office space here, apparently, as well as cheaper housing (try finding that in shouting distance of Bunhill Fields). And the listing is not a means for freezing the whole local area in time, which partly concerns questions of curtilage (although as things stand, most adjacent buildings are no more than four or five storeys high). And, of course, we've been here before ��� or if not exactly here, certainly hereabouts. I don't object on principle to the skyline changing. It's the disregard for history and quality of urban life, the flouting of the rules and intimation of how Johnson chooses to govern that disappoints ��� just these few, minor foibles.

Not least as, in the meantime, the Blake Society has been campaigning for years to erect a "traditional gravestone" in the correct spot in Bunhill Fields, and have been restricted to making it a flat stone "due to planning restrictions", for which funds are still being raised.

Perhaps Johnson could try reading a spot of Iain Sinclair, who gives a vivid sense of Bunhill's present and past commingled in this lecture from 2007:

"On a morning like this, it would be wonderful, with the trees overhead, the dappled leaves ��� there is a large fig tree that hangs over Blake���s grave. And it���s a place that is not in the City. It���s just outside the walls of the original City. Because once you go beyond, the permissions begin to open up. The original theatres grew up just on the edge of the City. The brothels, the liberties, the asylums grew up in Hoxton, on the edge, and in Hackney, because they���re the suburbs of the City. And in this place too the dissenters are buried. And I go through that place and sit down because it is a relief from any journey across town . . . . The place on the edge of the City is a place of respite and resolution."

In any case, unless many more people sign this petition, "Boris Johnson: We ask you to halt the development of towerblocks by Bunhill Fields", and a dramatic reversal takes place, I look forward to seeing Dissent-free City workers eating their packed lunches in the shadow of a tower block where once the earth was more open to the sky.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers