Wilde child

By MICHAEL CAINES

"What do you say to a simple inscription", Oscar Wilde wrote to a friend on December 7, 1886:

To the Memory

of

Thomas Chatterton

One of England's greatest poets and sometime pupil at this school

The plan for a memorial tablet to Chatterton on the fa��ade of his old school, Colston's in Bristol, came to nothing. Wilde and his friend Herbert Horne were not alone, however, in their admiration, as Wilde went on to show: "I was very nearly coming to fetch you the night of the fog to come and hear my lecture on Chatterton at the Birkbeck, but did not like to take you out on such a dreadful night. To my amazement I found 800 people there! And they seemed really interested in the marvellous boy". . . .

That last phrase, too, indicates something of the Romantic history of the Chatterton cult, since it is Wordsworth's (and you can hear it in the course of the latest episode of TLS Voices, embedded below). His other admirers included Keats, Coleridge and Southey (who co-edited his poems). Today there is a modern Thomas Chatterton Society, established in 2002, on the 250th anniversary of his birth; most unusually for a literary society, and with the poet's sorry fate in mind, one of its aims is to "highlight the needs of teenagers like Chatterton in modern society".

You can see from modern anthologies, on the other hand, that few still think that Chatterton is one of "England's greatest poets", as Wilde apparently did. Perhaps it doesn't help that the most notorious productions of this eighteenth-century teenager are those he attributed to a fifteenth-century priest called Thomas Rowley. Here is an eighteenth-century teenager doing an impression of a fifteenth-century priest translating a poem by an eleventh-century monk about the only eleventh-century event that would happen to mean anything to an eighteenth-century readership:

Kynge Harrolde turnynge to hys leegemen spake;

My merrie men, be not caste downe in mynde;

Your onlie lode for aye to mar or make,

Before yon sunne has donde his welke, you'll fynde.

Your lovyng wife, who erst dyd rid the londe

Of Lurdanes, and the treasure that you han,

Wylle falle into the Normanne robber's honde,

Unlesse with honde and harte you plaie the manne.

Cheer up youre hartes, chase sorrowe farre awaie,

Godde and Seyncte Cuthbert be the worde to daie.

(Is there also a hint of Shakespeare's King Henry V before the Battle of Agincourt at the end there?)

Of these medieval fantasies, supposedly discovered amid the lumber of St Mary Redcliffe Church in Bristol, with which Chatterton's family had long been associated, only one was published in his lifetime, "Elinoure and Juga":

Systers in sorrorwe, on thys daise-ey'd banke,

Where melancholych broode, we wyll lamente;

Be wette wythe mornynge dewe and evene danke;

Lyche levynde okes in eche the odher bente,

Or lyche forlettenn halles of merriemente,

Whose gastlie mitches holde the traine of fryghte,

Where lethale ravens bark, and owlets wake the nyghte.

(The quainte spellynges aside, you can see here, I think, why Chatterton thought his sentimental and Gothic forgeries might appeal to Horace Walpole, who had himself perpetrated a literary fraud in the form of The Castle of Otranto, supposedly translated from an Italian original and "found in the library of an ancient Catholic family in the north of England".)

Not many of the wiser sort were convinced of the authenticity of the Rowley poems, although a campaign of support was to outlive Chatterton himself, who died at the age of seventeen in 1770 (or killed himself, the mythologizers preferred to believe).

In turn, Wilde's admirers will know what that alarming word "authenticity" meant to him ��� this is the man who declared that "art's aim", in The Picture of Dorian Gray, is to "reveal art and conceal the artist". And that "One should always be a little improbable". And: "The first duty in life is to be as artificial as possible. What the second duty is no one has as yet discovered". A poet who seems to have lived by these maxims was bound to appeal to the aphoristic Oscar, as Nick Groom shows this recently published TLS review.

That makings of that lecture about Chatterton survive as a notebook that has caused some controversy: Professor Groom tells how some took its contents as evidence that Wilde was a plagiarist. Instead, we might now say, the notebook shows how Wilde was deeply interested in the marvellous boy. It helps us to see why he believed Chatterton deserved that memorial in his home town ��� and why he "remained a touchstone" in Wilde's work.

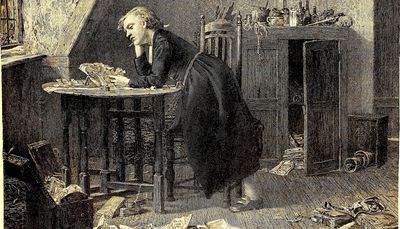

There may be a hint of him, for example, in the figure of the garret-bound writer in "The Happy Prince", for whom the prince has one of his own sapphire eyes plucked out. "I am beginning to be appreciated", the poor writer observes, on receipt of this gift. "'This is from some great admirer. Now I can finish my play', and he looked quite happy." It's not the only possible reading of that passage, but I like the idea of Wilde reversing what he called "the most tremendous tragedy in history" by way of this children's story. Chatterton himself would no doubt have loved the idea, and tried to put it into oldde englysshe.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers