Peter Stothard's Blog, page 15

December 11, 2015

You can't say that!

Omar El-Khairy, Sabrina Mahfouz, Ritula Shah and Shaista Aziz; credit: Rebekah Murrell/English PEN

By BENJAMIN POORE

Shoreditch can sometimes feel like the nadir of twenty-first-century triviality, so I was pleased to find myself, on Saturday afternoon, listening to a serious and clear-sighted discussion about freedom of expression in Rich Mix cinema. Discussions of this sort can be predictable, with attacks on political correctness, and libertarians demanding the right to say anything to anyone anywhere. Thankfully, none of the three panellists at English PEN���s "Crossing Borders" event once mentioned Voltaire.

Their conversation was shepherded (for a two-dozen-strong audience) with understated authority by the BBC���s Ritula Shah. "You Can���t Say That!" was part of a day of events organized by PEN, Rich Mix and the Arts Canteen with the title "Crossing Borders". The dramatist Omar El-Khairy spoke eloquently about the last-minute cancellation of Homegrown, his play about radicalization, by the National Youth Theatre earlier this year, after concerns were raised about its content. (I was pleased to read that it is now likely to be put on in the new year.) El-Khairy didn���t want to be seen as a free-speech martyr: ���I don���t want to be put in some kind of Salman Rushdie box���, he noted wryly.

The panellists��� experiences taught us that freedom of expression can emerge only in specific conditions and for specific people. Omar El-Khairy suggested that Homegrown might have been seen as a daring and sensitive intervention ��� and been staged ��� if it had been written by somebody else. The poet and filmmaker Sabrina Mahfouz spoke of a documentary she made about sex work; after Amnesty International produced a report recommending the global decriminalization of sex work, Mahfouz said the producers demanded that her piece take a position on this argument one way or the other. She said she was more interested in simply posing questions and allowing her subjects to speak for themselves. The programme was pulled. Freedom of expression finds itself under threat in certain contexts if it sails too close to ambiguity and ambivalence; or, to put it another way, we might say that sometimes expression is only possible if it operates within the established ways of speaking and thinking about a particular topic.

Shaista Aziz described her experience of making a BBC documentary (which was aired in the spring) about young Muslims in the poorer parts of Paris; saying "Je suis Charlie" demanded that they buy into a with-us-or-against-us narrative. Aziz and El-Khairy pointed out the troubled relationship the French Left (as well as the Right) have had with race and ethnicity. The arguments about Charlie Hebdo and free speech are perhaps less about freedom of expression in and of itself than they are to do with the terms under which you can be included within the liberal rhetoric of French republicanism. Aziz���s reflections suggested that not everyone gets to be French in the ways that supporters of Charlie Hebdo suggested were synonymous with the magazine.

At another event ��� the Arts Canteen���s "Uniting Rhythms", which was held on the main stage downstairs, in front of a packed audience ��� the Anglo-Iranian singer and tambok player Somaya gave us arrangements of Duke Ellington and Peggy Lee; and the spoken-word poet Fajr Tamimi, MC for the evening, read with defiance from her poem "The Tongue": ���So explain to me / one more time���, she intoned, each repetition growing in anger.

The night culminated in an extraordinary performance by Maya Youssef, who was playing the Kanun, or Qanun, a seventy-two-string harp with a history in various parts of South-eastern Europe and the Middle East. Youssef is studying for a PhD at SOAS, and uses music in her work with Syrian refugee children. She was trained in Western, Arabic and Azerbaijani classical and folk music, and this tangle of influences gives her performance an astonishing contrapuntal intensity. At certain moments, we could have been listening to the Goldberg Variations, or a sonata for harpsichord by Alessandro Scarlatti; at others, we were somewhere else entirely.

Those intertwined musical traditions offered an artistry of striking delicacy and immediacy ��� and affirmed the artistic possibilities that come from "crossing borders".

December 10, 2015

Roland Barthes and the Citro��n DS

Citro��n DS 19 (Photo by Auto BILD Syndication/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

There���s a nice review in this week���s TLS of a novel about Roland Barthes. La Septi��me Fonction du langage by Laurent Binet (Grasset) imagines Barthes���s assassination (���Who killed Roland Barthes?��� asks the cover line of the book). The writer was in fact knocked down and killed by a laundry van in Paris in 1980.

Barthes���s centenary fell on November 12, and was marked by an exhibition at the Biblioth��que nationale de France earlier this year. Binet���s centenary tribute is rather more irreverent. In his highly entertaining novel, Michel Foucault is depicted with a rare degree of insolence: accosted on the steps of a packed amphitheatre in the Coll��ge de France by Jacques Bayard, the police officer in charge of the investigation into Barthes���s murder, ���he looks at the hand gripping his arm as if it was the biggest assault on human rights since the Cambodian genocide���.

This insolence is extended to living figures: the writer Philippe Sollers, who has already appeared in a less than flattering light in Michel Houellebecq���s fiction, is lavishly sent up, as is his partner Julia Kristeva. Bernard-Henri L��vy also makes an appearance. I wonder what they make of the novel.

Also given more than a roll-on part in the novel is the fabled Citro��n DS, or D��esse (Goddess) as it soon became known. Contemplating the wrecks of two cars implicated in the crime, Bayard wonders ���Why a DS? Production stopped in 1975". And began in 1957. In his essay on the ���New Citro��n��� (published in Mythologies, 1957), Barthes writes: ���I think that cars today are almost the exact equivalent of the great Gothic cathedrals: I mean the supreme creation of an era, conceived with passion by unknown artists, and consumed in image if not in usage by a whole population which appropriates them as a purely magical object��� (translation by Annette Lavers). I particularly like that enormous white steering wheel. And does anyone who ever rode in the back of one recall how the suspension would rise when the key was turned in the ignition? A unique sensation.

December 8, 2015

Letters from Greece

Athens. Credit: Dimitris Karaiskos

By ROZ DINEEN

Not long ago, we were hearing a lot more from Greece, but while the debt crisis has hardly passed, the coverage has certainly diminished. The story that 700,000 migrants arrived in Greece this year has understandably overshadowed the machinations of the Greek Parliament as it reluctantly approved an austerity budget for 2016 that will include significant increases in privatization. Perhaps we will hear more from our news outlets when measures to double the income tax for Greek farmers and a new round of pension cuts are put forward. Perhaps not. A recent, harrowing episode of Crossing Continents on BBC Radio 4, Greece: No place to die, reported on the exhumation of graves which are often only rented for a three-year period.

There is appetite for stories that emerge from impossible situations. The Syrian refugee crisis has given rise to several admirable examples (such as this, this and this). But this sort of long-form reporting doesn't suit all publishers; it is often deemed too expensive to create and too time-consuming to digest.

Step forward Letters from Greece from the innovative digital publishers The Pigeonhole press. The Letters were curated by the Greek literary agent Evangelia Avloniti, and they arrive to Pigeonhole subscribers in instalments on any device. Its beautiful illustrations include works by the New York Times contributing photographer Eirini Vourloumis.

One of the stand-out letters is by Angela Dimitrakaki, a celebrated Greek novelist and a senior lecturer in History of Art at the University of Edinburgh. She revisits a topic she has written about before, the distinctive apartment culture of Athens, and depicts the atmosphere of life in this city. In short: everything is awful and, at one and the same time, not so bad.

Dimitrakaki recounts what it���s like to return to Athens from abroad:

"When I used to live mostly in Britain, I expected not to see the infamous Athens traffic jams upon my return, thinking that no one could afford petrol any more. Despite the frequent phone calls home, despite my regular travels back and forth, despite my formal training in suspecting the media of, well, lying, descriptions of Greek destitution were impossible to dislodge from my head. After as little as five days away from the apartment, I would start questioning my first-hand experience of the reality of Athens."

Another man returning to Greece is Peter Papathanasiou, who was born in Florina but then adopted by a family in Australia. In his dispatch, he has returned to see his biological brothers and renew his Greek identity card. He occupies the ideal insider-outsider position from which to relate to us the intricacies of a different culture:

���The taxman or inspector comes to your shop, fakelaki. You open any business, build anything, go anywhere, you need the magic fakelaki. It���s the way business works. Without it, nothing happens. It���s an ancient and noble tradition. Like growing your best olives on land the taxman can���t find.

My brother had also told me a story about my adoptive mother, who came from Australia to adopt a Greek baby from an orphanage. She had been living in Australia for so many years that she didn���t offer a fakelaki, thinking they no longer did that in Greece. She walked away from the orphanage empty-handed. Had she remembered the time-honoured custom, she would not have asked my biological parents to have another baby, and I would never have existed.���

As he recounts his trip, Papathanasiou also traces his grandfather's harrowing journey from Anatolia to Greece in 1923 as an Orthodox Christian refugee at the time of a population exchange with Turkey. It reminds us of our continent's history of people escaping, on foot, with no aid, in desperation. Meanwhile, Angela sits in her apartment with friends whose lives have been diminished by the Greek crisis, watching videos of refugees in Calais and Macadonia. ���Our own city is full of pain, and who are we to be enjoying a fabulous risotto among people we have loved for years and others that we may love in the future? Guilt . . . . Heavy with stupidity, our times do not condone cultural openness. Our times display a collective preference for structures of withholding and patterns of exclusion, and for punishment."

In conversation with each other, the letters link the old news with the new. They leak word from inside not a single crisis, but a nexus of geopolitical and cultural events, that ��� for the usual purposes of the news ��� must be teased apart and simplified for consumption.

To read A. E. Stallings's Freelance column of February 27 ��� "Snow on the ground, The Clash in the air ��� and Cavafy in Parliament" ��� click here.

December 4, 2015

Tintin in the house

�� Herg��-Moulinsart 2015/Somerset House - Installation image

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

���What if I told you that I put my whole life into Tintin?��� asked Herg�� shortly before he died in 1983. The man who revolutionized the cartoon strip and influenced the work of Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol is the subject of a nice little exhibition at Somerset House, Tintin: Herg�����s masterpiece (admission free, until January 31, 2016). There is also a book to accompany the exhibition (published by Rizzoli).

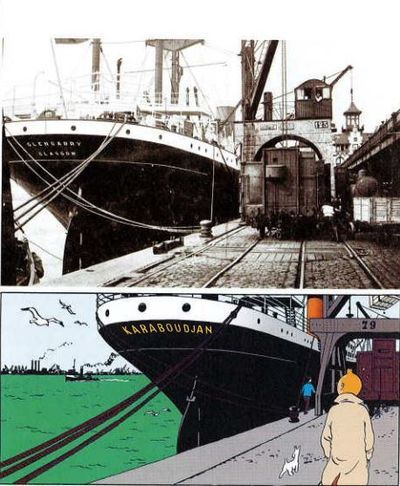

As the publicity claims, the exhibition enables us to step ���inside the wonderfully eccentric world of artist-author Herg�� and Tintin, his intrepid young reporter��� (who, it should be said, never files a report or ages a day across his twenty-four books). The walls of the three rooms replicate the famous pastel-blue and white inside covers of the albums. There are also models of Captain Haddock���s chateau, Moulinsart (Marlinspike Hall in the English edition), and of Tintin���s anonymous apartment in Brussels. Herg�����s interest in architecture and design can be seen in the many precise drawings on display, many of views from windows. As Michael Farr points out in his indispensable Tintin:The complete companion (2001), everything was drawn as close to life as possible, from Bauhaus chairs to ships��� rigging.

The Glengarry of Glasgow was used as a model for the Karaboudjan (from Michael Farr's Tintin: The complete companion

The last time the cub reporter floated into public consciousness was with the appearance of Steven Spielberg���s shockingly bad computer-animated film The Adventures of Tintin (2011). Spielberg had harboured an ambition to film a Tintin adventure for over three decades and Herg�� reckoned that he was the only director ���who could ever do Tintin justice��� (in the words of Herg�����s biographer Pierre Assouline,"he considered Spielberg a genius"), so disappointment at the result was felt all the more keenly by Tintinophiles. Herg�� had agreed to Spielberg���s request for "sole artistic and commercial control of the project", which might explain the ill-judged liberties the director took with the stories. (A superb theatrical version of Herg�����s own favourite Tintin in Tibet, in London in 2006, revealed how adaptable his work can be.)

Meanwhile, Herg�����s star shows no sign of waning: a drawing from Tintin in the Congo sold at auction in Paris recently for ���770,000.

December 2, 2015

Iris Murdoch: letter-writer and eucatastrophist

By MICHAEL CAINES

"Dearest girl a RING! Thank you so very much. And what a lovely one ��� obviously magic ��� a ring of power. I think it is made of mithril. (I hope you know your Tolkien.)" The author of these words, Iris Murdoch, sent them to her dear friend Philippa Foot on December 23, 1969 ��� within a few years, as far as I can tell, of Murdoch starting to write her letters at the desk of the author she perhaps somewhat surprisingly alludes to here. . . .

Tolkien was surprised, at least. As noted in the TLS back in October, the Oxford philologist-novelist had, in 1965, received a "warm fan-letter" from the the Oxford philosopher-novelist. A recently published essay (by Scott H. Moore, in Tolkien among the Moderns) suggests that the affinities between the two of them run deep: troubled by what she saw as the potentially dubious consolations of fantasy writing, her own novels nonetheless reflect Tolkien's concept of the "eucatastrophe" ��� not a sudden, sweeping disaster but a sudden, sweeping miracle that puts everything right. A. N. Wilson, who knew Murdoch and was taught by Tolkien's brother Christopher, has observed that neither author could be considered an especially talented stylists (that most deadly of literary virtues). Both preferred ���simply charging on��� as they told their tales; their conversations, to Wilson's horror, could turn on ���abstruse points of elvish lore���.

So to those prepared to put their novels side by side, perhaps the connection is not so surprising after all ��� maybe think of them as novelists who are equally concerned with the struggle between good and evil yet take different routes to encompass that struggle.

Not that Murdoch was uncritical of Tolkien. In January 1969, twelve months before demonstrating to Foot her knowledge of metals peculiar to Middle-earth, she had asked one of her students at the Royal College of Art: "Have you read Lord of the Rings yet I wonder? I have just been reading The Hobbit which has some very good scenes in it. (Tolkien muffs all the big scenes in L of R I'm afraid ��� it should be much more drawn out)".

It's a long time since I read Tolkien, so I can't say if she's right about that failing (can you?). But this observation does put me in mind of those drawn-out scenes in Murdoch's own fiction. She excelled in devising such atmospheric sequences: Jake's pursuit through the streets in Under the Net; the two boys clinging to the ominous tower (it "emerged blackly against a black sky") in The Sandcastle; Ducane, Pierce and Pierce's dog Mingo (some thoroughly Murdochian nomenclature there) trapped in a littoral cave by the rising tide in The Nice and the Good (that cave has a chimney; imagining escaping that way, Ducane realizes the water "would rush up that narrow sloping hole like a demon . . .").

One more Tolkien���Murdoch connection: both were prophetically praised in the TLS on the publication of their first works of fiction, Under the Net appearing to its anonymous reviewer to show that "the gifts which have gone to its making promise great things", and The Hobbit, two decades earlier, being hailed as a likely "classic" for the future. The critical prophet, admittedly, being Tolkien's friend C. S. Lewis.

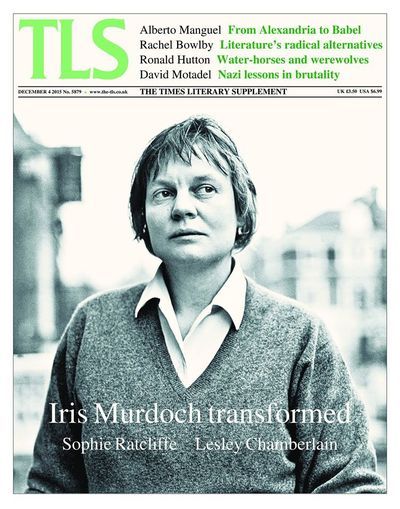

Both of the letters quoted above appear in Living on Paper, the generous selection of Iris Murdoch's letters recently published by Chatto and Windus; a photograph of the celebrated roll-top desk is reproduced here, too, in its place in the study "where Murdoch would sometimes spend up to four hours a day writing letters", after doing a day's work at the desk in her other study. While noting those passing references to Tolkien, I've been reading the volume's many letters to Brigid Brophy with a certain interest. Sophie Ratcliffe's review leads this week's TLS, which some may enjoy reading, its superior critical qualities aside, in the wake of a complaint from Avril Horner and Anne Rowe, the editors of Living on Paper, about how other reviewers have portrayed the author ��� as ruthless, "morally bogus" and so on. Amid the usual mixture of howling-mad and sensible comments in response to them is a reply in the latter category from one of those reviewers, John Sutherland. A review of a review of some reviews, you might say; this one could run and run. (Let's hope it doesn't.)

By quiet contrast, the most recent edition of the Iris Murdoch Review, produced by Horner and Rowe, among others, pays tribute to Murdoch's husband John Bayley, and includes his correspondence with Michael Howard. Bayley introduces her in 1955 as "Earning about 2 x as much as I do & wedded to literary ambitions": "We are much in love, & live in great harmony & domesticity". So how about a quotation, from 2004, for the paperback edition of Living on Paper?

"Funny thing letters. Iris was one of the worst of correspondents, perhaps because she always conscientiously answered every one she got, and there were a great many, often fairly dotty. When I was courting her, and wrote her what you might call long and pseudo-brilliant letters, I always got a few ��� a very few ��� hasty but kindly words in reply. Letters were emphatically not her mode of expression or being . . . ."

OK, perhaps not. . . .

November 30, 2015

The Blank Page by Jon McGregor: National Conversation

Jon McGregor. Photo credit: Dan Sinclair

This is an extract from Jon McGregor's provocation delivered at the final event of Writers��� Centre Norwich's National Conversation, Cambridge Literary Festival, on November 29.

Picture the typical literary event: there will be a long, narrow room, with chairs set out in straight rows. The audience members will gather in attentive silence. The writer will stride confidently to the front of the room, be introduced by an event organizer, pour himself ��� and the default image is, still, of a him ��� pour himself a glass of water from a jug on a low table, and move across to the lectern to begin.

From this lectern, the writer will talk for a time about their latest novel: how the research was done, where the idea came from, how the idea was developed, what a personal struggle it was to wrestle this beast into being . . . they will give a lecture about themselves, essentially, often for many long minutes.

They will then read some pages from their novel, with much harrumphing and mumbling and fiddling with bifocals.

This reading may go on for some time.

The audience will politely pay attention.

The author will then be ushered over to a comfortable chair on the stage, and joined by one or two others on equally comfortable chairs, there to have a conversation with each other to which the audience is expected to listen.

The conversation will be about the writing of the novel, or the argument of the novel; the author will be given the opportunity to very gently defend or justify what they have written. The conversation will then be "opened up" to the audience; meaning that the more confident members of the audience will call out questions to which the writer is expected to respond instinctively.

. . . the entire format is based on a nineteenth-century idea of the public intellectual: the lectern, the lecture, the silent audience, the spirited conversation, the debate; even the wine.

It's a format that deliberately privileges those from a specific cultural and educational background ��� the privately educated, the Oxbridge educated, those who have grown up with dinner parties and salons and debating clubs, those who feel comfortable and confident holding forth, those who expect to be listened to.

This all makes sense, of course. It's entirely fitting that the novel should be presented and discussed in settings such as these. Because the novel itself is a peculiar artefact, a product of a very particular socio-economic class. That the telling of stories was devolved to the object we call the novel is an historical anomaly born out of a particular set of technological and economic circumstances: printing technology, the availability of a specific size of leather binding, the educational shift from Latin to English, and the growth of a leisure class with the time to read long novels and the disposable income to collect them. And wasn't that leisure class itself founded on the wealth drawn directly from the exploitation of the labouring classes, from the pillage of empire, from slavery? Shouldn't we consider the novel itself to be a freakish indulgence, forever tainted by the stain of colonialism and slavery, as ugly in its way as the stately homes and gilded statues which shame our landscape?

We've heard a lot, in previous contributions to the National Conversation, particularly from Kamila Shamsie and Kerry Hudson, about the lack of diversity in publishing, and about the stifling of voices that results. But this lack of diversity is more pervasive than even these previous contributions to the National Conversation have suggested. The problem is one of structure. The problem is one of form. The entire culture and apparatus of the published novel was developed by an economic elite with leisure time on its hands, and the descendants of that class work to perpetuate an environment in which their own sort feel at home, while others are accepted only as hyphenated anomalies: the working-class-writer, the black-writer, the gay-writer, the disabled-writer, the woman-writer.

Here's my suggestion: if we want to open literature up to a much wider range of voices, and if we really want to hear the stories our fellow citizens have to share, we could start by entirely revising our idea of how we expect writers to behave; how we expect them to look; how we expect them to present their work to us when we ask them to perform. We could remind ourselves that we do have these blank pages from which to work.

We could start by getting rid of the lecterns . . . .

I'm not asking for the wheel to be reinvented every time a writer appears in public. Some events in the traditional format can be wonderful: captivating, surprising, engaging, revelatory. Some writers are comfortable reading at a lectern, and holding forth from a stage; some of those are even quite good at it.

But other writers are better at small talk, in small groups. Some writers benefit from preparation and rehearsal and can perform their work wonderfully, but not talk about it coherently afterwards. Some writers can work with musicians, or theatre-makers; some can work well alone; some prefer the intimacy of a bookshop; others, the privacy of a brightly-lit stage. Some writers can communicate wonderfully through social media, while an actor performs their work. Some events in the traditional format suit some of the writers, some of the time. But they exclude many writers ��� or, at least, squeeze them into uncomfortable positions in which they struggle to thrive ��� and they exclude great swathes of potential audiences.

This exclusion ��� this exclusivity ��� should be a matter of urgency for all of us who care about literature . . . .

This is an extract from a piece commissioned by Writers��� Centre Norwich for the National Conversation #NatConv

To read the piece in full, click here.

The Williamsburg Independent Film Festival

By CATHERINE HIGGINS-MOORE

On November 19 I walked four artfully grafittied blocks from my apartment, through biblical rain, past neighbourhood restaurants and construction sites boasting new high-rise apartments, to the sleek Wythe Hotel in Brooklyn. I was there for the opening night of the sixth annual Williamsburg Independent Film Festival ��� a festival that boasted entries of over 220 films, shorts and features, submitted by writers and directors in twenty-five countries. The aim is to "nurture and celebrate new and independent filmmakers in the mecca of hipster and progressive culture, Williamsburg Brooklyn���.

Relieved to be inside, and out of what New Yorkers simply refer to as ���weather���, I took my seat in time to catch the festival's opening short, In Transit, directed by Justin Van Voorhis. In Transit tells the story of two ���unique individuals��� who meet on a ���fateful day��� in a bus station. It was disappointingly saccharine; the script inchoate, the acting of the sort that makes leads in films you���ve never heard of on Netflix look Oscar-worthy. In film number two, We Just Met, directed by Khawaja Muneeb Hassan, it distracted me that the Irishman whose ���surprise visit to his NYC girlfriend results in being snubbed, then inadvertently involved with a conniving, thieving fun loving female��� was played by an antipodean. I waited for this to be explained; to be a plot point. It wasn���t. I waited for the female lead, short film���s answer to the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, to morph in to more. She didn���t.

Hassan���s stock characters and paint-by-numbers script did not engage me, but I was struck by how much money had obviously been poured in to making it; I am thinking in particular of a lengthy dance scene shot at Bethesda fountain in Central Park and involving a large troupe of dancers. Later, I talked to a young director at the festival who told me his $15,000 budget was donated by his parents. When I asked what they got from investing, aside from their son���s happiness, he told me that they both had ���creative input. My dad was a producer���.

���And your mother?��� I asked.

���She worked in craft services.���

The festival���s third offering was a welcome change of pace: an engaging film based on a true story. In Cameron Fife���s Buckeye, Donald Webber Jr. gives an outstanding performance as a homeless man in New York who saves his money for a plane ride to a warmer climate. For the first time in the evening, a film���s score added to its story rather than making it sound as if a DJ had started playing in a room next door. In a particularly well-observed moment, a man queues behind Webber���s character in a pizzeria, only to cover his mouth and nose with his scarf and exit without ordering. Buckeye was the opening event���s stand-out film, and Fife, who was in town to star in the Midtown Theatre Festival, is surely an actor/director to watch.

Gail Lerner���s Toygantic was the final film of the four opening shorts. A mockumentary exploring the history of a toy ocean liner from the 1960s, Toygantic was well told and poignant in parts. Lerner exploited the intimacy that comes of the ever-popular faux-documentary style, although since her film is twenty-seven minutes long, the joke eventually wore thin. It was surprising that Lerner, who used to work on a network comedy show, could not ramp up the humour that was always threatening to burst forward.

In the end, one has to wonder if having another festival like this is just a vanity project for its founders: it offers no funding or training to aid those filmmakers whose work it needs to exist. Given that Bushwick has widely been christened "the new Williamsburg", perhaps the Bushwick Film Festival, with its panel discussions and local sponsors, is the place to look next year for emerging filmmaking talent. And while the Wythe is a magnificent venue with an intimate screening room, if the aim is to foster and welcome the young artists of tomorrow, a more fitting space might be one where a glass of wine can be had for under ten dollars.

November 27, 2015

Robert McCrum's hundred best novels

By WILLIAM REES

There is something rather curious about the ���hundred best��� list (see Michael Caines's posts "Not the hundred best novels?" and "The hundred most influential books since the war?"); after all, putting the vote to the public or, worse, a cadre of self-elected experts almost never results in anything that will meaningfully diverge from an all-too-well-known canon. And yet we are compelled, time and again, to draw up endless variations of the same list, and to read them. Even those of us who have not contributed to an ���official��� list have probably drawn up hazier versions in our imaginations, perhaps as we stare at that familiar patch of ceiling above our beds.

Why?

Last week, with this question firmly in mind, I made a rare trip to Piccadilly Circus to attend an event at Waterstones promoting Robert McCrum���s The 100 Best Novels in English. The book���s cover tells us that it is affiliated with The Observer ��� but as the lack of the words ���edited by��� in front of McCrum���s name implies, it was compiled not by committee but by a single person. For two years, McCrum wrote about one book each week for the Observer, and the entries have now been compiled in an elegant hardback. Nice work if you can get it.

McCrum was an amiable host. At one point he told us of the hefty manuscript that he rejected when it landed on his desk at Faber. Its title was Infinite Jest. Later, he spoke about the obscurity in which Herman Melville lived after the publication of Moby-Dick, and posed the tantalizing question: who are the Melvilles of today? He went on to tell us ���the problem with the contemporary novel��� (not enough passion, apparently).

The evening had an informal tone, and McCrum was keen to hear the small audience���s views on what should make the cut. Our suggestions were every bit as predictable as his; and while that���s not necessarily a bad thing, it does suggest that we are all now quite used to this. Of course, McCrum���s choices are only part of the interest; it���s the way he speaks about those choices that really counts, and he did so with tenderness and flair. But browsing McCrum���s list, it looks oddly like one that has been compiled by committee, and there is little in there that is likely to surprise. One might expect an industry man like McCrum to have chosen a few lesser-known works ��� works whose inclusion might have challenged our idea of ���best���. But, then, we don���t read these lists to be surprised, do we?

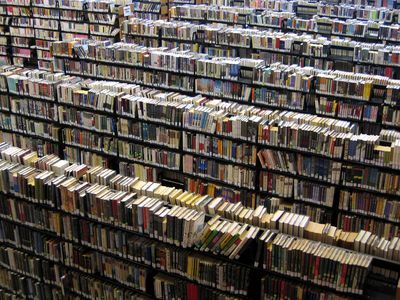

Which raises once again our opening question. What makes us endlessly reaffirm the value of Swift, Sterne and Steinbeck? Why are we so drawn to these lists? Maybe it���s that, in the face of an endless list of potentially life-changing works of art, these lists feed the fantasy of mastery. Who hasn���t been appalled, on visiting a library, to be confronted not only by all the fantastic things one hasn���t read, but also by the realization that one will never read the vast majority of them?

In answer to this anxiety, the ���hundred best��� list offers a soothing balm. It does this by way of a clever ruse, making mastery at once difficult enough to be worthwhile and easy enough to be achievable. And for those who find a hundred books a little daunting for a single lifetime, a growing list of books like McCrum���s offers a compelling and entertaining shortcut.

November 25, 2015

Eliza Soane commemorated

By MICHAEL CAINES

As mentioned by Mika Ross-Southall on this blog last month, the new exhibition at the Soane Museum surveys a morbid scene: if there is one architect who could inspire an exhibition entitled Death and Memory, it's Sir John Soane. Not content with imagining his Bank of England as a ruin, and commissioning Joseph Michael Gandy to depict such scenes for him, he turned his own house into a delirious reliquary, abounding in statuary and other fragments of antiquity, including several cinerary urns and an alabaster pharoanic sarcophaghus, through which to educate and overawe posterity.

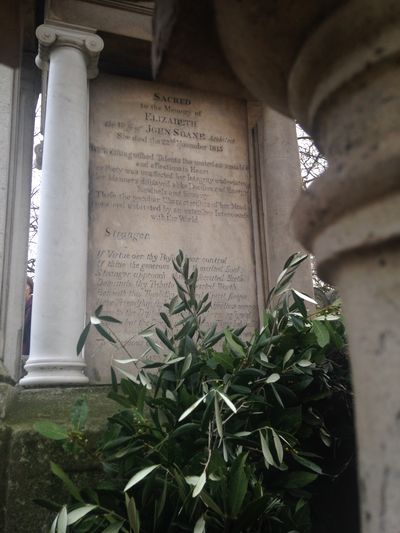

But not Soane's own posterity ��� not the sons he had hoped would continue his work. Indeed, when his younger son George published two anonymous attacks on his father's architectural achievements, in 1815, Soane regarded them as his wife Eliza's "Death Blows"; she died a few weeks later, on November 22 that year. There was to be no Soane lineage of architects, at least not directly; instead, there is his museum. And there is also the remarkable mausoleum where some thirty people gathered on Monday to pay tribute to Eliza. . . .

The 200th anniversary of Mrs Soane's death was a Sunday, and deemed to be impractical, so a brief ceremony was held the following day, on November 23, at the Soane mausoleum in the churchyard of St Pancras Old Church. It was here in the mid-1860s, about fifty years after her death, that the young Thomas Hardy oversaw a mass excavation of bodies, as thousands of graves made way for the Great Midland railway out of the new St Pancras railway station (where George Gilbert Scott built the Midland Grand Hotel; it was his grandson Giles who took inspiration from the Soane mausoleum for the British red telephone box).

Hardy captured something of the atmosphere of the place in his poem "The Levelled Churchyard", written at a later date, and partly with reference to similar works in Dorset:

O passenger, pray list and catch

Our sighs and piteous groans,

Half stifled in this jumbled patch

Of wrenched memorial stones!

We late-lamented, resting here,

Are mixed to human jam,

And each to each exclaims in fear,

"I know not which I am!"

(Note the characteristically strange yet striking use of the word "jam" . . . There is also, to take this digression even further, a more recent and superbly ghastly take inspired by these experiences, The Hardy Tree by Iphgenia Baal.)

No such rotten luck for Eliza Soane and the remaining son, John, and the husband who were later to be interred with her. Set within the bounds of a circle of iron railings, the Soane mausoleum still stands within listing-and-catching distance of the chuntering trains going in and out of St Pancras. Its isolation is nothing like the romantic scene pictured by George Basevi in 1816 ��� but it is also nothing like the "jumbled patch" Hardy saw assigned to the residents of the neighbouring graves, and certainly not "crowded", as a fellow journalist recently put it. On the contrary, it is appropriately set apart, a monument without a trace of Christian imagery in its design (Soane, a Deist, disliked organized religion) making its bold architectural statement in the grounds of an Anglican church. To me, it has always seemed surprisingly modest in scale, compared to Basevi's depiction. Intimate or domestic even ��� as might be thought fitting for a family tomb.

After the necessary warm drinks in the church itself, we ambled across the churchyard, and the gate into that iron circle was opened for us. The museum's Acting Director, Helen Dorey, gave a speech, noting Eliza's own collecting activities and how vital she was to her husband. (Dorey is also giving a talk about "the Soane as a shrine" tomorrow night.) It seems to have been a happy marriage, of three decades' duration; although readers of Gillian Darley's John Soane: An accidental romantic will know that there were rougher times as well as smoother ones, there is no doubt he was devastated by her death. A "delightful, perceptive" person, Eliza had "acute intelligence" and a "shrewd head for business". The Soane library of some 6,000 books is not exclusively his collection, but includes some titles with her name inscribed in them: Lady Mary Wortley Montagu's Letters; Samuel Johnson's Dictionary; a second-hand copy of Elizabeth Griffith's Essays Addressed to Young Married Women. Eliza Soane also, Darley suggests, "brought Soane the personable architect into being", playing the "socially adept" hostess and the "confidante". He needed such guidance. Could it be said that he was, in some sense, her great achievement?

Soane's grief found expression in the mausoleum he designed for her, erected in 1816; he could not then bear to go and see it for himself. The wreath laid there on Monday was a reminder that anybody who admires his work is in Eliza Soane's debt, too.

Paris - writers' responses

Cynthia Fleck holds a drawing of the Eiffel Tower during a rally of solidarity at the Consulate-General of France, Atlanta, Sunday Nov 15 (AP Photo/Branden Camp)

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

How have writers in France reacted to the appalling events of November 13? After President Hollande���s eloquent statement of resolve to the two chambers of the French Parliament on November 16 ��� ���Je veux que la France puisse rester elle-m��me��� ��� and the unanimous vote for a three-month state of emergency have come the expressions of shock and disbelief: that a second atrocity could hit Paris in the space of ten months, and on a much larger scale, and with such apparent randomness.

With a horrible irony or prescience, Le Monde of Saturday 14 (which went to press before the attacks) carried a long article by the psychoanalyst Fethi Benslama about the ways in which, for some ���desperate people, radical Islam is an exciting product���.

In a symposium on November 20 in the same paper, which solicited the views of twenty-nine writers, there was a unanimity of sentiment but some divergence of opinion. The novelist Olivier Rolin ��� not one to mince his words ��� rejects the notion that the atrocities ���have nothing to do with Islam . . . . Jihadism is undoubtedly a disease of Islam, but it has exactly the same relation with that religion as a disease has with the body it���s devouring. ���It���s a tiny minority.��� Without doubt. But several thousand ���radicalized��� [people] in our country is no small matter. The leftist groupuscules of the post-68 years (to which I belonged) were scarcely more numerous. Or the Russian Bolsheviks, but that didn���t stop them from constructing one of the two great totalitarian systems of the XXth century���.

Agn��s Desarthe, who lives near the Place de la R��publique (i.e. near where the attacks took place), on a more personal level describes how from 10 pm onwards people started calling to check that she and her family were ok. ���Our children frequent the places which we���re now seeing images of on TV on a loop.���

The Egyptian writer Alaa El Aswany, meanwhile, points out that ���millions of us owe a lot to France ��� access to art, . . . culture, the principles of the Revolution . . . . Ever since the XIXth century most Egyptian thinkers and writers have been francophone���.

Genevi��ve Brisac points out that in the past it was the far-right Front National that used to get ���pissed off��� at France���s youth. Now Islamic State has targeted that demographic, describing Paris as the ���capital of abominations and of perversion���.

According to Joyce Carol Oates, writing from the US, ���For many of us Americans, Paris is the ideal city, the most beautiful city in the world, and to see it hit right in its heart is shattering . . . . Parisians��� refusal to be intimidated is a model for all nations���.

The Goncourt Prize-winning J��r��me Ferrari takes a more jaundiced view: ���Who would dare criticize this society that is so festive, so subtly transgressive that it provokes, through its very perfection, the rage of these bad people [m��chants]?���

In the weekly journal Le Point, the Paris-based British writer Andrew Hussey (author of The French Intifada: The long war between France and its Arabs, 2014) writes of how the riots in 2005, ruthlessly quelled by the Interior Minister Nicolas Sarkozy, were a ���prelude��� to recent events. The novelist and member of the Acad��mie fran��aise Amin Maalouf predicts that the struggle against Islamism will last beyond his generation. More provocatively, Kamel Daoud, the author of the acclaimed anti-��tranger novel Meursault, contre-enqu��te (The Meursault Investigation), writes: ���All this comes from one matrix, one country, one kingdom: there���s no point in fighting against a badly dressed Daech in Syria while shaking hands with a well-dressed Daech in Saudi Arabia���.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers