Peter Stothard's Blog, page 19

October 6, 2015

Michael Holroyd at 80

Michael Holroyd, 2011; �� Geraint Lewis/Writer Pictures

By RUTH SCURR

Last night the Royal Society of Literature hosted a celebration of Michael Holroyd���s eightieth birthday at the British Library. Hermione Lee led a panel of biographers ��� Patrick French, Richard Holmes, Jenny Uglow and me ��� discussing Holroyd���s work and his influence on our own biographical practice.

There was a high level of consensus: Holroyd is nonpareil. He can do more in a single sentence than lesser writers manage in a whole page. For example, when writing of Winnaretta Singer, one of the many children of the American sewing-machine multibillionaire: ���Her first marriage, a distressing experience involving an umbrella, had to be annulled���. . . .

His ears ringing with our praises and gratitude, Michael came on stage and said he felt elevated into a new fictional character called "Holroyd". Concerning "Holroyd" he had this to say: experience shows us our ignorance. The young Holroyd ���entered other people���s lives to get away from his own���. Mature Holroyd, looking back on his work, reminded us that Virginia Woolf thought she knew everything there was to know about biography, until she sat down to write one of her friend Roger Fry. She wanted to bring him back to life on the page, she thought she might write his life backwards, she thought she would revolutionize the genre, but in the end fell back on a conventional model. Experience shows us our ignorance.

Michael read two short passages to add to those the panellists had chosen from his work. The first was a description of George Bernard Shaw, in his ���young eighties��� enjoying gardening:

���Chopping wood, making bonfires, sawing logs, collecting acorns, eyeing the strawberries while patrolling up and down with his notebook, camera, and special secateurs, he appeared to one neighbour ���like a magic gardener in a fairy story���. He would write in the garden too, stepping out from a veranda at the back of the house (���my Riviera���) and hurrying past the flowers and trees to a small revolving hut, like a monk���s cell, with its desk and chair and bunk. Here in what some visitors mistook for a toolshed, he was conveniently out of the staff���s way and the world���s reach.���

The second was an autobiographical account of ���Illness in England���, ending with a call from a journalist wanting ���A couple of facts about your schooling, if you don���t mind���:

���Really? What for?���

���Your obituary.���

I paused. ���Who are you?���

He named a name ��� and a newspaper ��� and with mingled feelings I gave him the facts as I remembered them.

���Is that all?��� I asked tentatively.

���Yes. I think that completes it, thank you.���

For the time being.

After that, Michael rejoined the audience. The panel set off on a broad discussion of biography and its challenges past, present and future. When the question of Facebook, Twitter and email arose, we ventured some tentative thoughts on how social media might change biographical practice. Hermione Lee, with characteristic incisiveness, turned quickly to Michael and asked: ���Are you on Facebook or Twitter?��� ���Not to my knowledge���, he replied.

Michael Holroyd, Hermione Lee, Ruth Scurr and Patrick French; �� Dylan Spencer-Davidson

October 5, 2015

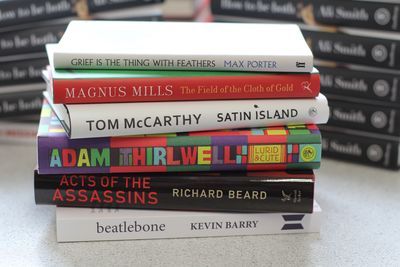

Not the Goldsmiths Prize?

By MICHAEL CAINES

The Goldsmiths Prize is, many people seem to agree, a very good thing. It seems to put the whole dubious mechanism of modern literary prize culture to critically serious use; it has brought about what Ali Smith has called the "miracle" of encouraging publishers to take risks on relatively experimental works of fiction.

Feel free to reply: "Well, she would say that, wouldn't she?" For Ali Smith won last year's prize, with How To Be Both; before her, there was Eimear McBride, who won the inaugural prize in 2013, for A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing. Both women seemed to be favourites to win. This year, however, all that can be said with certainty is that the Goldsmiths winner will be male. . . .

That's because this year's shortlisted books are all by men ��� there was a "low number of eligible entries by women", according to McBride, who is one of this year's judges. Given the Goldsmiths prize's "previously unblemished record", she writes, "hopefully" (ahem) this will turn out to be an anomaly ��� a "blip".

For the obvious reasons (in this day and age . . . and all that jazz), I share that hope. Just for the critical hell of it, though, with respect to the Goldsmiths judges, and more in tribute-to than competition-with them, here is an alternative, all-female list: fiction published this year that "breaks the mould or opens up new possibilities for the novel form" (and happens to be written by women).

Every year, the Guardian runs an enjoyable sideshow to the Man Booker Prize: the Not the Booker prize, in which the process of choosing the best novel of the year is thrown democratically open. This year, for example, out of a long list of seventy books, a shortlist of six has emerged and almost 1,000 votes were cast. Let's hope the voters have voted for books they've read ��� "I seem to be the only person on the planet who has read all the entries on the shortlist. Or even, possibly, more than two of them", Sam Jordison, the Not the Booker's Ion Trewin, wrote a few years ago (is there no end to the vitiating mishaps of the judging process?).

No, I don't think the Goldsmiths Prize is in need of a similar annual sideshow. And we're not in the prize-giving business. For this year only, though, maybe an alternative shortlist would be a good idea. There'll be no voting, no money changing hands; these six choices are based on nothing more than asking around, some idle Twittering and some recommendations from the TLS's fiction editors. No publishers should slap "Shortlisted for the Not the Goldsmiths Prize" stickers on their stock ��� as if they would.

In fact, most significantly, we've veered away almost entirely from the Goldsmiths concentration on novels ��� so this is "Not the Goldsmiths" in more senses than one. You could see this as conceding the point about "eligible" titles ��� or perhaps we could say that veering is what "new possibilities" is all about, and much of the interesting work is happening around the borderland between short story collections and "fully fledged" novels.

Further recommended veerings are welcome. What are the books that, in the words of the Goldsmiths website, evince a "spirit of invention that characterises the genre at its best"?

The winner of the Goldsmiths Prize will be announced on November 11.

1 Pond ��� Claire-Louise Bennett. "Unified and hallucinogenic" stories, the critic John Self told me the other day ��� a short story collection but narrated by a single narrator. In the (temporary) absence of a TLS review, why not read his? Or Ruth Gilligan's?

2 Don't Try This at Home ��� Angela Readman. Already the winner of various awards. Described by its own publisher as quirky (hmm). Reminiscent of Angela Carter and Katherine Dunn, says For Books' Sake. That's more like it.

3 An Account of the Decline of the Great Auk, According to One Who Saw It ��� Jessie Greengrass. One story here begins: "Sometimes I dream that there is still the internet". It begins with the title story and proceeds ��� via "On Time Travel", "Winter 2058" and "The Politics of Minor Resistance" ��� to "Scropton, Sudbury, Marchington, Uttoxeter". What, you need to know more?

4 The Measure of Reality ��� Maija Timonen. Stories, in some cases just single paragraphs, described on the back cover as "Funny, mordantly sexy, witty, true". I'm not sure about the "sexy" part. There's a bleak wind of loneliness blowing through the life of Timonen's female, city-dwelling protagonist. And there's absurdity, too: the obsession that grows out of smelling a neighbour's aftershave; the way "I'm OK" sounds less convincing the more it is repeated ("I'm OK. I'm OK. I'm OK. I'm OK . . ."); panicking when trying to find a reference in book and thus making it more difficult to find the reference.

5 Devotion ��� Ros Barber. Every reviewer of this book is honour-bound to point out that her first, The Marlow Papers, wasn't in prose. This automatically, undeniably makes Devotion a departure ��� "not quite as profound as I had anticipated", the Independent's reviewer wrote, but a near-future "page-turner", nonetheless, about science and religion. The Financial Times found it "challenging and at times a little confusing", but was impressed by Barber's precise language, as was the TLS's Catherine Higgins Moore, who quotes one character's observation that "Unconsciously we are casting spells on ourselves . . . . Language is how we create the reality we live in".

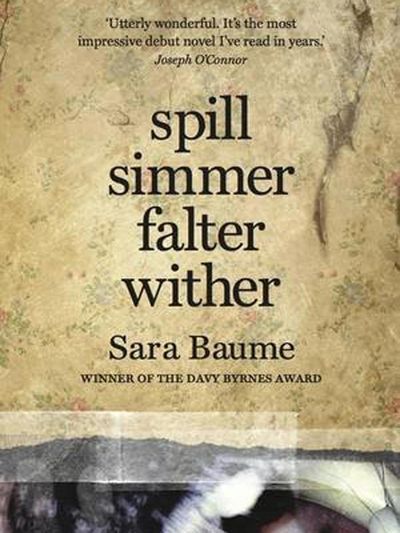

6 spill simmer falter wither ��� Sara Baume. One Irishman and his rescue dog. Described by David Collard in the TLS as "engaging, intriguing and brightly original first novel may mark a comparably significant debut", although the "nameless protagonist never fully convinces . . . because the author seems deliberately to avoid settling on a persuasive voice".

October 2, 2015

John Clare and the remnants of the fairy days

By MICHAEL CAINES

Here's a gladdening thought: By Our Selves, Andrew K��tting's "abstract documentary" about the poet John Clare and his "Journey out of Essex", is out today. I blogged about this film last year, when it was in production but also in need of crowd-funding. Quite rightly, the crowd helped out ��� so here it is . . . .

By Our Selves has shifted in shape over the past year ��� I saw a mesmerizing live version at the Battersea Arts Centre, some time before the great fire that consumed that particular part of the building, with a wild dance courtesy of that straw bear, and the woods somersaulting deliriously on screen.

Yet the film is what it promised to be last summer: a quietly humorous, sometimes disquietingly giddy memorial in monochrome to that uncertain post-asylum progress of July 1841, with a befuddled soundtrack and an equally befuddled Toby Jones as Clare (a part also played by Jones's father Freddie, in a more conventional Omnibus documentary in 1970). We watch as Clare meanders softly through the woods, patched at the elbows, gypsy-abandoned hat in hand. He stops near roaring roads. A merry and thoroughly modern band tread the same path. The straw bear bemuses passers-by in Peterborough.

Interspersed interviews, with Moore and others, suggest how that hapless journey home continues to fire people's imaginations, not least because it was so evocatively recorded by Clare himself. "I thought as I awoke somebody said 'Mary' but nobody was near", he recalled. "I lay down with my head towards the north to show myself the steering point in the morning." Hunger and confusion take over:

"I sat down half an hour and made a good many wishes for breakfast but wishes was no hearty meal so I got up as hungry as I sat down ��� I forget here the names of the villages I passed through . . . ."

As the filmmakers candidly admit, By Our Selves might be around, on limited release, for a week only ��� so catch it while you can. This may be your only chance, as pictured above, to see a film starring Alan Moore, a straw bear, the singer MacGillivray (ghosting the part of Clare's dead lover Mary) and a sometime TLS contributor, Iain Sinclair, in a goat mask.

The poetry, meanwhile, will wait for you. Is he still an underrated writer? Surely not . . . but as a modest beginning, if you've not read Clare before, here are fourteen lines that John Fuller thought fit to stand opposite Shelley's "Ozymandias" in the Oxford Book of Sonnets. And for another conjuration of Clare's wandering spirit, see Anthony Hecht's "Coming Home", another creative response to the "Journey out of Essex", first published in the TLS in 1976.

The Ants

What wonder strikes the curious while he views

The black ants' city by a rotten tree

Or woodland bank. In ignorance we muse,

Pausing, amazed. We know not what we see,

Such government and order there to be:

Some looking on and urging some to toil,

Dragging their loads of bent stalks slavishly,

And what's more wonderful, when big loads that foil

One ant or two to carry quickly; then

A swarm flocks round to help their fellow men.

Surely they speak a language whisperingly,

Too fine for us to hear, and sure their ways

Prove they have kings and laws, and them to be

Deform��d remnants of the fairy days.

JOHN CLARE

September 30, 2015

Who is your most overrated author?

By TOBY LICHTIG

In early 1977, to celebrate its seventy-fifth birthday, the TLS ran a special issue in which a score of literary luminaries was asked about the authors who, in their opinion, were most underrated ��� and overrated. The exercise was brilliant because of the people polled: Anthony Powell, Roland Barthes, Christopher Isherwood, Philip Larkin, Vladimir Nabokov, William Empson, and many others.

The responses were suitably forthright, provocative, amusing. Hugh Trevor-Roper considered ���the whole Bloomsbury group ��� excepting only J. M. Keynes ��� to be the most overrated literary phenomenon of our times��� ��� and Lytton Strachey to be its charlatan-in-chief.

Rebecca West dismissed Leo Tolstoy for the ���sheer nonsense��� of Anna Karenina; Larkin chose D. H. Lawrence, mostly on the basis of Women in Love (���boring, turgid, mechanically ugly���). Readers were treated to a gnomic Bob Dylan (���Overrated and underrated: the Bible���), a paranoid Karlheinz Stockhausen (���for security reasons I cannot name the book which I consider to be ���the most over-estimated������) and a plainspoken Thomas Balogh (���Michael Arlen ��� identified with the essential snobberies of the British as only a foreigner could���).

In the ���overrated��� category, several authors were selected more than once: J. R. R. Tolkien, Ezra Pound, Arnold Toynbee, Sigmund Freud. E. M. Forster was chosen both by Anthony Powell, for his ���bland self-satisfaction���, and Anthony Burgess, for his lack of ���creative potency���. Andr�� Malraux cropped up three times, an interesting reflection of the era. Who now rates Malraux at all? For Barthes, Malraux was imaginatively ���feeble���, for Hugh Trevor-Roper one of ���the great charlatans���, for Richard Cobb quite simply ���fraudulent���. (Cobb also scorned James Joyce as ���arrogant, unpleasant, and above all, quite unreadable���). Those under attack, by a tacit gentlemanly agreement, were all dead ��� though not necessarily for long. Malraux had been in the grave for barely two months; Isaiah Berlin���s choice was Hannah Arendt, who died in late 1975.

The ���underrated��� sections, though less entertaining, were no less instructive. (It may be noted that John Betjeman and David Hockney were too kind to damn anyone, as was Nabokov, R. D. Laing and Lord David Cecil.) Some of those cited remain underrated ��� which is to say that I for one have barely heard of them. Who now reads (or ever read) Maurice Baring, Leo Shestov, Lucien L��vy-Bruhl, John O���Hara, Forrest Reid? Some, such as John Cowper Powys (selected by Angus Wilson), have just about been rehabilitated. Conversely, it now seems amusing to see Italo Calvino (chosen by Eric Hobsbawn) in the ���underrated��� category, given the widespread hero worship he continues to provoke, particularly among undergraduates. As in so many things, Hobsbawn was ahead of his time. So, too, was Michal Dummett, who selected Ralph Ellison for Invisible Man�� ��� a novel that can hardly nowadays be described as overlooked.

The biggest winner from this special issue was Barbara Pym, chosen by both Cecil, who described her books as ���the finest examples of high comedy to have appeared in England during the past seventy-five years���, and Larkin: ���the six novels Pym published between 1950 and 1961 ��� give an unrivalled picture of a small section of middle-class post-war England���. The story has now become a part of TLS, and wider literary, lore. Pym, who had been out of print for several years, really was brought in from the cold on the back of this support, and she went on to publish several more novels. She continues to be widely read, and enjoyed, today.

Why am I raking over all this now? Well, on Sunday (October 4) we'll be reprising the jape in the form of a debate I���ll be chairing at the London Literature Weekend. It's on at King���s Place at 6.30pm. I can���t offer you Nabokov or Rebecca West, and Dylan was otherwise engaged (he���s playing at the Albert Hall; as it happens). I can, however, offer a suitably stellar panel, comprising the author-critics and TLS stalwarts D. J. Taylor, Claire Lowdon and Jonathan Keates. I won���t give away who���s in the firing line ��� and who���s being given a boost ��� but you can take my word for it that some eyebrows will be raised. Of course, you can always come along and see for yourself. Tickets are available here.

As for my own choices: I���ll stick for now to the studied neutrality of conscientious chairmanship, but I was amused this afternoon to receive an email from Intelligence Squared telling me that Karl Ove Knausgaard ���is widely described as one of the greatest artistic geniuses alive���. I���m a big fan of Knausgaard, but I wonder if the modern media penchant for superlative praise makes this game even more relevant today. After all, how many other heroes of our times would you consider just a teensy bit over-praised? Haruki Murakami? Hilary Mantel? Elena Ferrante? (I don't really mean that last one: I just thought I'd try to raise some hackles.) More to the point, who are the real charlatans? And who deserves a boost?

Feel free to comment at the end of this blog, or reply by tweet, and I���ll do my best to get in a mention of your choices at the start of the debate.

September 29, 2015

The Forward Prize

DAVID HORSPOOL

Claire Harman

Congratulations to Claire Harman, whose poem "The Mighty Hudson", about a New York strongman (first published in the TLS), has been awarded the Forward Prize for Best Single Poem 2015. In an interview on the Forward site, Claire, better known as a biographer and critic, reveals that she is a prolific but mostly unpublished poet. In fact, she says, only four of her poems have been published. I wonder if any other poets can claim that a quarter of their published oeuvre is prize-winning?

Next week's TLS also happens to feature an article in Commentary by Claire Harman about Charlotte Bront��.

September 26, 2015

Trollope: Something for the (London Lit) Weekend

This time next week, I'm very happy to say, the London Lit Weekend, produced in association with the TLS, will be under way at King's Place. There'll be talk of overrated and underrated authors (suggestions welcome), inequality and what to do about it, the Notting Hill Editions essay prize, the Battle of Agincourt, Mrs Thatcher in fiction and much else besides, including some chat about this:

This is the work of the artist and comics expert Simon Grennan, who has turned Anthony Trollope's late novel John Caldigate (1879) into Dispossession, a "novel of few words". Indeed, the page reproduced above is a typically deft rearrangement of relatively few words from its source. (In the novel, Dick Shand declares of their fellow passenger, without needing to assert that he and his college friend John are gentlemen: "She is a mystery, and mysteries are always worth unravelling. I shall go to work and unravel her".) Other panels and pages pass wordlessly, making a fresh adventure out of Trollope's own.

As part of the London Lit Weekend, I'll be discussing Dispossession next Saturday, and Trollope in general, with Simon Grennan, Professor Helen Small (who has edited both The Eustace Diamonds and The Last Chronicle of Barset), Jonathan Keates (whom I strongly suspect of knowing everything, as well as being able to write beautifully about anything) and John Sutherland (likewise). As already mentioned on this blog, on our podcast TLS Voices and in the TLS itself (by Professor Sutherland, among others), it's Trollope's bicentenary this year ��� not a bad moment to be revisiting Barsetshire or the sometimes surprisingly wider world that the novelist covered in the course of forty-seven novels and numerous works of non-fiction.

Stories set in Australia, Egypt and Ireland reflect his fascination with the fate of English men and women abroad, as well as those who come home but, as in John Caldigate and Dr Wortle's School, cannot escape the malign clutches of the past. There is an abiding irony in the series of travelling narrators who find themselves unable to escape the company of their compatriots, either, however far they go. Over the course of his prolific literary life, Trollope covered a full spectrum of Victorian obsessions: the Church of England and its politics; problems with money and class; sex and marriage. Trollope never lost his admirable knack for coining a ridiculous name: President John Neverbend, Ontario Mogg, Sir Harry Hotspur of Humblethwaite, Lady Selina Protest.

Perhaps his own name will come up at the end of the London Lit Weekend, too, in the course of that discussion of the overrated and underrated, authors with "undeserved reputations" and those who have been "unfairly overlooked". Trollope has been regarded as both over the years. His Autobiography suggests that he himself regarded Lady Anna as his best novel ("Quite far away above all others!!!" ��� sic), while Ralph the Heir was "one of the worst": "a novelist after fifty should not write love-stories". Is He Popenjoy?, despite its splendid title, will strike many modern readers as Trollope at his most wrong-headed, for its attack on the "nascent women's rights movement". On the other hand, he dared to write in favour of Radicalism in Lady Anna and everywhere spies out pride, vanity and the other little quirks of character that could make comic characters of us all. If he lacks a modern-day counterpart, there is at least Dispossession to prove that a story of his can be translated, with unexpected ease, into a highly modern idiom.

September 22, 2015

Sven Hassel and books for boys

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

The Danish writer Sven Hassel wrote fourteen novels set during the Second World War. The second of these, Wheels of Terror, which was first published in 1959, has just been reissued by Weidenfeld & Nicolson (Paperback, ��8.99), in anticipation of a graphic novel version by Jordy Diago, which Weidenfeld are bringing out in October.

Alan Sillitoe, the author of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, is quoted on the back cover of Wheels of Terror: ���This is a book of horrors, and should be left alone by those prone to nightmares . . . a great war novel!���. Well, that last point is highly disputable. Under the rubric ���Great War Novels��� I would put All Quiet on the Western Front and Gabriel Chevallier���s Fear, the Sword of Honour trilogy and Catch-22, among many others. But not Wheels of Terror, which is certainly brutal, remorselessly, almost monotonously violent and crude. The narrator Sven is in the fictional 27th (Penal) Panzer Regiment. The misfits and chancers of the 27th, who are regarded as entirely expendable, find themselves on the Russian front, where the fighting is at its most ferocious and shambolic, and the Geneva Convention is routinely flouted. The main character Joseph Porta is a lanky Communist sympathizer from Berlin; there���s a certain irony in the fact that he has been sent to fight against the Red Army (���Ivan���). Sven writes that ���we cared nothing for the Fatherland or Hitler���s war-aims. We fought only for our lives���.

The dialogue, at least in I. O���Hanlon���s translation of 1959, is frequently terrible (it may be better in the original Danish): ������We���ll burn the fat off Hermann [Goering]���s backside when we have our revolution,��� hissed Porta���. ������Soon we���ll be back at the front and then we���ll see what���s in you, you Schleswig bible-puncher������. ������You call our F��hrer crazy? I���ll take a note of that!������ Comical . . .

Are Hassel���s books anti-war novels or glorifications of military violence? Hassel would claim they fall into the former category, written by a witness to terrible events, and it���s probably fair to give him the benefit of the doubt. The author was born Sven Pedersen in Denmark in 1917. After a period of unemployment he appears to have joined the Wehrmacht in 1937 and taken part in several campaigns, including the Russian one. In a Guardian obituary of the writer in 2012, Dan van der Vat wrote ���Mystery surrounds the events of [Hassel���s] own life���. The Danish journalist Erik Haaest, meanwhile, alleged that Hassel never served on the Russian front and that he got his information for his books from Danish Waffen SS officers. But Haaest also denied the existence of the Nazi death camps, so maybe his claims should be treated with scepticism.

Britain accounts for some 15 million of Hassel���s worldwide sales of over 50 million books ��� a figure rather dwarfed by the late Jackie Collins���s 400 million. He was certainly popular when I was at school in the 1970s (his Monte Cassino was much passed around). His books fed a seemingly insatiable appetite for WW2 and Cold War spy stories, or tales of baddies intent on world domination. Into the mix I would also throw the novels of Alistair MacLean (my own favourite), Desmond Bagley and Hammond Innes. None of them had any literary pretensions, I sense, but they wrote exciting, well-plotted adventure stories. The anonymous TLS reviewer of MacLean���s Ice Station Zebra (1963) praised the way in which ���the story evolves in a succession of masterful puzzles as astonishing as they are convincing���. Does anyone recall MacLean���s The Guns of Navarone (made into a good film with Gregory Peck, David Niven and Anthony Quinn), Where Eagles Dare (film version with Richard Burton, Clint Eastwood and Mary Ure), or Caravan to Vaccar��s?

And then there was the former Times man Ian Fleming, whose James Bond novels were essential reading. I worked my way through the thirteen books in fairly short order. The Fleming world view is terribly politically incorrect of course: the back cover of my Pan edition of Dr No describes the Dr as ���a ruthless, power-crazed Chinaman���, while Le Chiffre in Casino Royale is a ���formidable, dangerous French Communist with large sexual appetites���. Of the wonderfully named Vesper Lynd (in the same novel), Fleming wrote, ���the conquest of her body would each time have the sweet tang of rape���. A pre-teen reader in the 70s would have been oblivious to the offensiveness of such an observation. The actor Daniel Craig recently criticized Bond's Neanderthal attitudes towards women. He has a point.

September 21, 2015

From Bronte to Bront��: where Sicily meets West Yorkshire

Il "Castello" di Nelson; �� REDA &CO srl/Alamy

By THEA LENARDUZZI

To a list of overlaps between Sicily and Yorkshire ��� plentiful and vertiginous dry stone walls; the flat cap (or coppola); gratuitously calorific cakes; a quintessentially ���rugged��� landscape which can make even the most mediocre novel/TV adaptation sing ��� I can add another: the Ducea di Nelson, an impressive abode which sits on the border between the communes of Maniace and Bronte, about 60km north of Catania.

Though generously elevated to the rank of a ���castello��� by the Sicilians, the Ducea is in fact an old abbey, founded by Queen Margherita di Navarra in the twelfth century, and gifted by Ferdinando III di Sicilia (as he was known until 1816, after which, for various complicated reasons, he became Ferdinando I delle Due Sicilie), to Admiral Nelson, in 1799, in recognition of the Englishman���s vigour in fending off the French. From then on, Nelson could call himself Duke of Bronte ��� and indeed he did, on every document he signed thereafter.

The pile, along with its 200 hectares (reduced from the original 15,000), is now open for public perusal and I was lucky enough to find myself in its vicinity last week. (Which is more than can be said for Nelson himself: there is, a plaque begrudgingly concedes, no evidence of the landlord ever having visited ��� though his descendants, the Nelson-Bridports, lived there, bar a few years of Fascist appropriation, until the 1970s.)

If you can ignore the palm trees outside the bedroom windows and the scorched hills which rise up to meet Mount Etna in the south-east, the Ducea is the kind of English Country House you���d expect to find in any of the more wealthy Shires. The rooms, hung in shades of custard, scarlet or Brunswick Green (very ���Now��� in the late 1700s), are dark, almost cold in spite of the 30-odd degrees C outside, and bedecked in gilt-framed paintings of Lord Nelson and his exploits. (You'll find a pretty exhaustive slide-show of the house and parts of the grounds here.)

(An odd aside: the Scottish poet, William Sharp, who spent his final years in the house as a guest of the Nelson-Bridports, is buried in the small cemetery to the side of Nelson���s chapel. He is ��� at the time of going to press ��� the only writer I can think of who chose to write under a female pseudonym, going beyond the gender-obfuscating initials favoured more recently, to become Fiona MacLeod.)

It���s in the accompanying literature that the Yorkshire connection is spelt out, albeit with attendant it-is-saids and as-the-story goes: so deeply admiring of the Admiral was a certain Patrick Brunty, who signed up to an undergraduate course in Theology at St. John���s College, Cambridge, in 1802, that he swapped the fenian-sounding "y" of his name for a more Continental "e" ��� umlauting it to avoid mispronunciation. It���s a name he took with him, following ordination, to a small parsonage perched on a hill just outside Keighley, West Yorkshire, and which went on to echo far beyond those less decorous walls.

A poem written in 1814 to commemorate the death in battle of the Duke of Bronte, by the parson���s only son, Branwell ��� incidentally, the least successful of all the Bront��s ��� makes clear the esteem in which the family continued to hold that ���star of glory���, ���Thunder bolt of war���. (Branwell was not known for the originality of his verse.)

As far as I know, no documents ��� official or otherwise ��� have been unearthed to prove the integrity of the Bronte-Bront�� connection once and for all, but it is nevertheless a tasty morsel brought out to please the tourists (myself included). The irony over the discrepancy between visitor numbers at the Bront�� parsonage (who can arrive in Haworth on a gloriously kitsch steam train) and the ���castello��� di Bronte is something to ponder over coffee and a couple of cucchie di petralia, a local pastry which tastes like a cross between a mince pie and a Betty���s shortcake piglet. Almost as delicious as the way the brontesi might pronounce ���Keighley and Worth Valley Railway���.

September 18, 2015

Corb our enthusiasms

By MICHAEL CAINES

We couldn't help it: eventually, a dangerous enthusiasm for the work of certain poets had to show itself via TLS Voices, the TLS podcast, and here it is . . .

In case you missed it: Robert Potts spoke last week about J. H. Prynne's To Pollen and the images of suffering so acutely accounted for by Susan Sontag in On Regarding the Pain of Others:

And here's a word from me about The Infant and the Pearl (1985), Douglas Oliver's highly personal, idiosyncratic pastiche of the fourteenth-century dream vision Pearl, in which a twentieth-century dreamer ��� a dreamer of the 1980s, more specifically ��� goes on a grimly satirical tour of Margaret Thatcher's Britain. Not only a tour: with a nightmarish ease, the "lyric subject", as Andrea Brady has put it, becomes "personally implicated" in "brutal Tory politics and City greed".

Despite the references to video screens and Cabinet ministers of that era, I couldn't help thinking that perhaps such a vision held some relevance for British politics today ��� a whole week on from the announcement that Jeremy Corbyn (a socialist of the same mould as Oliver's father, perhaps) has become leader of the Labour Party. But let's not get into all that now . . . .

Those eager to discuss literature, the current scene and that old one are directed to Mrs Thatcher and the Writers at King's Place, London, on October 4; a former Editor of the TLS, Ferdinand Mount, is one of the speakers, alongside Jonathan Coe and D. J. Taylor.

September 16, 2015

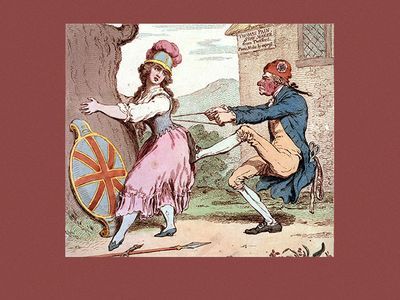

Deattributing Thomas Paine

���Fashion before Ease ��� or ��� A good Constitution sacrificed for a Fantastick Form���, 1793, by James Gillray: Thomas Paine���s Rights of Man is shown as a tape measure hanging from his pocket

By DAVID HORSPOOL

We don���t often do scoops at the TLS, and a History Editor is used to being teased that his idea of a scoop is a story about something that happened more than 200 years ago. But this week we are running an article in our Commentary pages by the distinguished historian and long-cherished contributor Jonathan Clark, "Monuments to Liberty", in which he argues that Thomas Paine didn���t write part of Rights of Man. And not just any part, but the bit that describes the run-up to and early weeks of the French Revolution.

Those 6,000 words, Clark contends, have skewed the way we have interpreted the French Revolution ever since. We have taken them as the authority of an eyewitness, a man who was present not just at the French but also the American revolution, and knew whereof he wrote. But many of the events Paine describes in fact happened before he arrived in France, and he couldn���t have understood many of the ones he did bear witness to, as he couldn���t speak French. The implications, Professor Clark argues, are profound for our understanding of an epoch-changing event. So, if he���s right (and he has an intriguing suggestion for who did write the passage in question), I think we have a story.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers