Peter Stothard's Blog, page 21

August 20, 2015

Chatto Poets at the LRB Bookshop: Liz Berry, Helen Mort, Sarah Howe

From left to right: Liz Berry, Helen Mort and Sarah Howe

By THEODORA HAWLIN

How does a poet become a poet? Helen Mort ��� whose debut Division Street (2013) was shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize and the Costa Prize ��� puts her poetic leanings down to the fact she was a lonely child and her parents didn���t own a television. Everything she fed-off was audio, the radio, bed-time stories. She talks fondly about the importance of the Young Foyles Poetry Prize ��� which she won five years running ��� and how it helped shape her identity as a writer. ���It gave me something better than money ��� the chance to escape to where talking about poetry was normal���. The prize ��� an Arvon residential writing course ��� gave her the chance to engage with other young writers in a safe environment, ���an invaluable experience���.

For Sarah Howe, whose recent debut Loop of Jade (2015) was shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection, poetry sprung from a similar yearning towards sound. Her inability to understand her mother���s native tongue when in Hong Kong was central to how she engaged with language and how it could be manipulated. The winner of the Forward Prize, Liz Berry with her collection Black Country (2014),credits her upbringing ���my mother and father loved poetry ��� we were very old fashioned ��� we learned poems off by heart���.

Compared by Ian McMillan this exciting triple-bill of readings began with Mort, a poet who ���can���t help but be political ��� we see things in brighter colours up where we live��� (the extremities of the North play a crucial theme throughout the night). Mort���s new poems highlight the influence of technology; even late night television-watching of a documentary on the brothels of Sheffield produces a rhyming sonnet on a prostitute who believes she���s saving lives. A ���found poem���, in which Mort splices together a Wikipedia article on the changing nature of women���s fashion from the 1920s with an internet forum on miniskirts juxtaposes the two worlds with cunningly placed rhymes of hysterical harmony. Mort revels in the ridiculousness of it: ���Things people say on the internet are far more surreal than in real life���.

Berry is a poet who is single-handedly changing attitudes towards the neglected Black Country, celebrating the unique tones of its dialect. She recasts its language to create something profound, selecting details that stick as in ���The Night You Were Born��� where she conjures the ���red tent of legs��� from which her partner emerges from his mother at birth. Yet it is her reading of her poem ���Bird��� that stands out. A Kafkaesque metamorphosis of girl to bird, with imagery that strikes with a visceral jab: ���I found my bones hollowing to slender pipes, / my shoulder blades tufting down. / I spread my flight-greedy arms / to watch my fingers jewelling like ten hummingbirds, / my feet callousing to knuckly claws. / As my lips calcified to a hooked kiss.���

Howe also presents a tale of transformation, a mother turns into a tree as she is beaten by her husband for not producing a boy: ���her scar-ridged back, beneath his lashes, toughened to a rind; it split / and crusted into bark���. McMillan jokingly recalls his grandson���s comment on Howe���s collection ���it might be slim but it���s deep���, but the image is one he comes back to, praising her for producing a book in which a reader can ���take time . . . swim around inside���. She delivers what may be the most poignant line of the night at the end of her poem ���Tame���, in which a father unknowingly kills his daughter who has transformed into a goose: ���A single blow. Profit. Loss��� staccato and sombre.

As Ian McMillan so aptly introduces them ��� ���three fantastic non-metropolitan voices��� ��� these are poets that deserve to be heard.

August 17, 2015

Greek generosity

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

It was a curious sensation being on one Greek island (Z��kynthos) and reading about the migrant crisis on another (Kos). Kos is within touching distance of the Turkish shore and so a natural arrival point in Western Europe for refugees who have come overland from Syria. The Guardian���s correspondent on Kos, Patrick Kingsley, reported last week that whereas tourists were paying ���20 for a ferry trip to Turkey, refugees ���will have paid fifty times more to complete [the journey] in reverse���. Meanwhile, the UK recently pledged to take in 500 of the nearly 4 million refugees who have fled the war in Syria. Does this seem like an acceptable figure? Germany has already taken in some 30,000 and Norway, Sweden and Switzerland have each taken comfortably more than 500. Britain's reputation as a nation that provides a haven for the oppressed is being severely tested.

Z��kynthos, being in the Ionian chain in western Greece, is unlikely to face such an emergency. But Greece of course has its own existential crisis to deal with, and while the economic situation is said to be worse on the mainland, the islands have not been unaffected. Quite a few enterprises on the unlovely outskirts of Z��kynthos Town, for example, had gone to the wall. Some relief, though, comes in the form of tourism, and it will be interesting to find out, sometime later this year, what effect this summer���s season has had on the Greek economy. On Z��kynthos, I was told that tourist numbers were down this year (anxiety about empty ATMs, etc), but not dramatically.

Over the past ten years I���ve gone to the Ionian Islands several times and have fallen in love with them: volcanic Kefaloni�� (of Captain Corelli���s Mandolin fame), beautiful Corfu, and now Z��kynthos, or Zante as its Venetian occupiers named it. The most southerly isle of the Ionian chain and no more than 50 km from top to bottom, it looks northwards to Kefaloni�� across the narrow strait which was at the epicentre of the earthquake that devastated the two islands in August 1953, and is some 25 km from the Peloponnesian shore to the east. It has its own airport (as so many Greek islands now do), where, hearteningly, the cash tills were ringing in the departure lounge duty free store.

Whatever their economic woes may be, the Z��kynthians appear not to let these divert them from their innate sense of hospitality and generosity. In common with their fellow Greeks, they may have had their taxes increased, their pensions cut, their savings decimated and been told that they���re going to have to work for extra years, but this doesn���t prevent them from giving a warm welcome to those who���ve come there, at least from my experience ��� and what a surprisingly cosmopolitan selection of holiday-makers there was: from Americans to Libyans to Poles. Little things come to mind: on the beach at Agios Nikol��os in the north of the island, the sunbeds are offered free (as is the parking); where else on the European Mediterranean shore would you encounter that? Meanwhile, hand-woven textiles are sold from people���s homes in the mountain village of Vol��mes for ridiculously small sums of money ��� along with the offer of a convivial glass of local wine. In general, people seem to work extraordinarily long hours (granted it���s the tourist season, and the most must be made of it, but even so). It is all quite humbling.

August 14, 2015

MacGuffins

John Travolta, Pulp Fiction, 1994

By ROZALIND DINEEN

There is a suitcase in Pulp Fiction about which there is much ado, the contents of which we never discover. This is a MacGuffin ��� a plot device, an object or a person, that drives the action so completely that the thing itself becomes meaningless. The black statuette in The Maltese Faction; the plans for the airplane engine in The 39 Steps; and (I am so very sure you won���t know this one) Doug in The Hangover, these are all MacGuffins. It doesn���t matter what���s in the suitcase; the statuette isn���t that interesting, who cares what happened to Doug ��� the point, the film, the story is in the search they engender.

MacGuffin is also the name of a new publishing initiative from Manchester���s sprightly and frequently brilliant Comma Press. This MacGuffin is a website (���a digital publishing platform���) on which writers can upload their work ��� text, audio and all. It���s free to access, and pleasing to look at. You can browse through the stories using hashtags (or help other readers by adding them). Comma���s digital editor recently explained: ���a crime-fiction fan on a 20-minute bus ride in south London could search #20minutestories #crime #lambeth to find a story suited to her journey���. And if that���s what people wanted to do, they could indeed do that.

Here���s the killer: the analytics for each story on MacGuffin are also clearly displayed. This means that all the writers involved know how many people have read their story, where in the world they were when they read it, and how many of them read it all the way through to the end. A graph for each story shows where people stopped reading ��� the ���key drop-off points���.

A burgeoning author could find all this quite helpful. If you know that 79 per cent of all your readers can not get past the same paragraph without throwing their device across a crowded Berlin caf�� or just leaving it in the loo in Miami International Airport, this may inform your editing process. Having said that, I���m not sure I���ve ever encountered a writer who would give up on the 21 per cent who kept going.

Can art be improved by consensus and approval? Of course not ��� but a certain type of readable and saleable writing can. The point here is in the search for, rather than the contents of, the work. A true MacGuffin.

I have my own list of ���drop off points���, by the way. There is one novel in particular, a novel that is about as successful as it is possible for a novel to be, which I have tried to read only about half a dozen times. When I get to the bit about the vase, something inside me rolls its eyes, and the book drops-off down the back of the sofa. Thankfully the author neither knew nor cared.

August 12, 2015

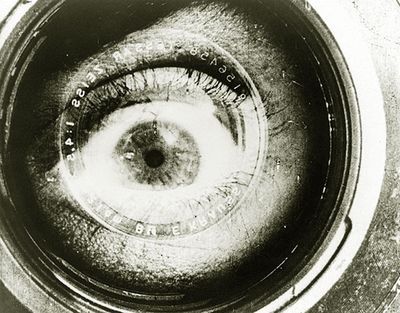

Man with a Movie Camera restored

A still from Man with a Movie Camera

By DAVID COLLARD

Is Man with a Movie Camera, a sixty-seven-minute silent film directed by Dziga Vertov in 1929, really the greatest documentary ever made? Yes, at least according to a readers' poll in Sight & Sound magazine. This came as no surprise to cinephiles ��� the film has topped so many lists over the past eight decades that it may be time to declare it hors concours and give some other contenders a chance. It is to documentary film what Ulysses is to the modernist novel and (it could be argued) the two masterpieces share a common approach and aesthetic. They are complex and minutely-detailed explorations of contemporary urban life and monumentally modernist. British audiences can judge for themselves this summer as a digitally restored print tours independent cinemas throughout the country . . . .

Man with a Movie Camera declares in its opening title card (itself a mini-manifesto) that the film was made without a script and contains no dialogue or inter-titles because it aims to offer an ���international absolute language���. This is not just an aesthetic gesture, but an attempt to overcome the daunting communication problems of a country with a vast range of languages and cultures.

The result remains to this day a thrilling and audacious work of art, still fresh, energetic, provocative and wonderfully funny ��� remote from the "tractors and wheat fields" clich��s of later Soviet propaganda. It is an unalloyed pleasure to watch, and re-watch, and not only for film-buffs.

The BFI Blu-Ray reissue features a fine musical accompaniment composed by Michael Nyman, while the big screen release has a score by the marvellous Alloy Orchestra, derived from the director's notes to his original composer, and so perhaps closer to what Vertov had in mind.

The disc comes with many extras, including Vertov's little-known sound film Tri pesni o Lenine (Three Songs about Lenin) from 1934, a slice of Stalin-era propaganda that admittedly features plenty of tractors and wheat fields, but a lot more besides. It was commissioned by Stalin to commemorate the anniversary of Lenin's death and to persuade the Soviet people that he was Lenin's natural heir. It's not as immediately engaging as Man with a Movie Camera and is less likely to appeal to a modern audience, but it is certainly worth a look, not least for its intriguing literary connection.

(A declaration of interest: my chance discovery some years ago of W. H. Auden's long-lost renderings of Russian peasant songs, turned into sub-titles for the first London screening of Three Songs about Lenin, led to an invitation from the BFI to provide an essay for inclusion in the booklet accompanying this release.)

In May 2009, the TLS published my Commentary on the Auden material ��� a bundle of manuscripts, typescripts and shot lists that record a brief collaboration between the poet and the Film Society's Ivor Montagu, a rush job calling for technical know-how which may be seen as a dry run for Auden's rhythmic, metronome-timed commentary for the celebrated Night Mail (1936).

Three Songs about Lenin was last shown publicly in Britain in 2009, at a BFI screening prompted by the rediscovery of the Auden verses. This one-off event was a partial re-creation of the original Film Society programme on October 27, 1935, a typically eclectic matinee that featured some German commercial shorts, a nature documentary about sea urchins, a dazzling abstract film by Len Lye and premieres of two films of lasting importance: Housing Problems, Arthur Elton's seminal study of the effects of poverty, followed by Coal Face (with its Auden madrigal and Benjamin Britten score). Some of these were screened before an expectant modern-day audience settled down to watch the main feature. I had seen it for the first time a few hours before at a trial screening and had been moved to see Auden's subtitles re-united with the original film. But that was in an empty theatre ��� this was in a crowded cinema.

In an early sequence in Three Songs about Lenin a Muslim woman removes her veil and joins a reading class in a village school. There were admiring murmurs in the audience and a ripple of applause as Auden's subtitles blazed on the screen:

My face in a dark prison lay

And blind my life remained

No learning mine nor light of day,

A slave although unchained

Till through my darkness shone a ray,

And Lenin���s truth I gained.

"Dziga Vertov" was the pseudonym of David Abelevich Kaufman, invariably and inaccurately translated by film historians in the West as "spinning top". The term really means "gyroscope" ��� not a nursery toy but, far more resonantly, a piece of kinetic precision engineering, a modern device for the machine age. As the current season of screenings suggests, "Dziga Vertov" runs on.

August 10, 2015

Inside the Fondazione Prada

Photograph: Bas Princen. Courtesy of Fondazione Prada

By KEITH MILLER

The fashion designer Miuccia Prada and the architect Rem Koolhaas have, over the years, forged what looks to the observer like a marriage of true minds. That distinctive eau-de-nil that you still sometimes see in Prada stores was his idea (well, technically it was Le Corbusier���s idea), and his practice-cum-think-tank OMA has worked on several sites for the designer, including a spatially exhilarating megapod in New York known, somewhat pompously, as the Prada Epicenter. Meanwhile the Fondazione Prada has supported OMA���s remarkably wide-ranging research into architecture, urbanism, shopping (���possibly the last public activity we have left���), airports and more.

Now, in an unimpeachably doleful location just off the outer ring road of Milan, the Fondazione has opened a gallery, or series of galleries, in an ex-distillery profoundly altered for the purpose by Koolhaas and his team; OMA is the named curator on one of the inaugural exhibitions, an absorbing if slightly tendentious survey of imitation and authorship in classical antiquity. A series of rooms displays pieces from Prada���s collection, alongside some deft loans ��� mostly but by no means exclusively mid-twentieth century, leaning a little on Italian artists that maybe don���t get the attention they deserve in international survey collections. There���s also a cinema, a ���triptych��� ��� three loosely related pieces by different artists installed in adjacent rooms - and several site-specific pieces, though one or two of these reminded me of things I���d seen on other sites, so perhaps their specificity is the result of some naturalization process.

Both Prada and Koolhaas produce work that one���s arch upper-middle-class grandmother, if one had an arch upper-middle-class grandmother, would characterize as jolie laide. They���re never content to make work that���s merely beautiful when they can produce work that is interesting ��� and in the process, both often attain a peculiar kind of beauty, clunky and complex and a little fetishistic ��� often, but not always. Contrast another Milan-based fashion titan, Giorgio Armani, who proudly proclaims his artisanal roots. Prada���s formative years, meanwhile, were concerned with mime, feminism, art history and Communism ��� she���s unlikely to have picked up a pair of scissors until she took over the family firm in 1978, and her first big success (those nylon handbags, versions of which are still on sale) had a kind of hard, industrial aesthetic: they were acheiropoietai, objects not made by human hands.

Armani���s work, meanwhile, is overtly concerned with beauty, albeit a rather bloodless, minimalist notion of beauty, and always cut with minute attention to the body. He has tended to work with architects at the Zen end of high modernism: recently and notably, he collaborated with Tadao Ando, on another non-specific cultural space, in another scruffy Milanese outskirt ��� the Armani Silos by the navigli, canals allegedly surveyed for the Sforza family by Leonardo da Vinci five centuries ago. The difference between Ando���s exquisite barely-thereness and Koolhaas���s brow-knitting, heavily textured, heterogeneous, contradictory maximalism couldn't be more pronounced ��� it���s as if two d��butantes had arrived at a party wearing, not the same dress, but two provocatively different ones.

Nevertheless, this time the Fondazione might just have pipped the Silos to the fabled golden apple. Koolhaas and OMA���s proclamations about urbanism and architecture have often been rather depressing, at least if you���re the kind of reactionary who prefers the Piazza della Signoria to the departure lounge at Schipol. Often there���s glib acceptance of aspects of globalisation and neoliberalism which ought in fact to be deprecated and resisted, and an almost cheerful fatalism about the erosion of public space (���junkspace��� is a characteristic shrugging coinage; ���fuck context��� is another ��� though the latter was framed quizzically rather than as an imperative).

But the gallery complex frames the objects with modesty and thoughtfulness ��� it���s very unlike recent showstoppers such as Frank Gehry���s Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. It toys with passing trends such as the ���dirty refurb���, to be sure; but carefully and even poetically, so you���re left with a rather poignant sense of the compound���s industrial past. It deploys lustrous and luxurious materials with irony, wit and a crisp formal cohesion: one block is externally gilded, another, of a different period and style, silvered; the sculpture show eschews the high pedestals on which such pieces were traditionally displayed in favour of a complex and richly refractive landscape of heaped-up square perspex slabs.

From "Serial Classic"; photograph by Attilio Maranzano; Courtesy of Fondazione Prada

A welcome feature of the Fondazione is Bar Luce, a flawless simulacrum of a child���s memory of an imagined 1950s Milanese espresso bar, with busy, sub-Fornasetti wallpaper depicting the celebrated Galleria Vittorio Emanuele, and formica tables in retro pastel hues. (Here was my only sighting of Koolhaas���s minty green ��� the twinkly-stern, grey-clad gallery assistants are more in line with Prada���s halcyon days some time in the mid-90s). The bar is apparently the invention of the film-maker Wes Anderson, who says it represents the kind of place he���d like to sit and work in ��� which tells you all you need to know about his work. Nevertheless, it���s a smile-inducing place, a world away from most gallery caf��s; it���s not madly expensive, and it has its own opening hours and front door, so it promises to make some sort of genuine contribution to the area which, on brief acquaintance, could sorely do with it.

Bar Luce; photograph by Attilio Maranzano; Courtesy of Fondazione Prada

As for the art ��� well, several pieces are genuinely world-class. There are a couple of excellent Louise Bourgeois, a ghoulish set of Keinholzes (���Wonderfully vulgar artist���, said Duchamp), a Joseph Cornell, a Sarah Lucas car (this in the obligatory Big Art room, alongside automobile-themed pieces by Elmgreen & Dragset and MVRDV, inter alia). The Italian modern stuff is an unexpected pleasure ��� or, in the case of a mirror piece by Michelangelo Pistoletto, an expected one. If you arrived thinking that the association of art and fashion was somehow trivializing, you���d find little evidence to support your prejudice (the whole thing seems much more high-minded than the Saatchi Gallery, say).

Sometimes the curation style dallies with Renaissance and baroque reference points ��� one room in the ���Introduction��� exhibition is a dense tapestry hang, which would be fine if you could get properly into the room; another sets the work in a little wooden aedicule; there���s even a grotto (Processo Grottesco by Thomas Demand). This may or may not be ironically meant: either Miuccia Prada sees herself as a kind of Isabella d���Este for our time; or she and her curators are alert to many people���s sense that the new plutocracies of our time, marching to power unopposed by the waning forces of social democracy, constitute a mirror���image of the petty despotisms that squabbled over ancien regime Italy, leaving chaos and destruction ��� plus the odd undying masterpiece ��� in their wake.

August 5, 2015

Spiegelhalters, Norton Folgate and the Water Poet

By DAVID COLLARD

Earlier this year I blogged about a campaign to save the fa��ade of an abandoned jeweller's shop, Spiegelhalters, in London's East End.

Property developers wanted to obliterate this plucky little structure and replace it with a glass atrium flanked by massive oxidized slabs, wiping out a century-old story and erasing what the great topographer Ian Nairn called "one of the best visual jokes in London". The campaign attracted thousands of supporters and widespread media coverage, perhaps because the stakes are immediately comprehensible ��� you don't have to be an architectural expert to see what happened here: a small family firm held out against bullying developers, and saw them off.

Six months after it was launched the campaign has now ended because the architects, Buckley Gray Yeoman, aware of public feeling (and perhaps belatedly realizing that they have a fascinating asset rather than a liability on their hands), have submitted revised proposals which incorporate the fa��ade . . .

Spiegelhalters remains a potent symbol of bloody-minded opposition and contrariness, qualities that are much needed today, as London disappears in a wave of speculative developments. News of another victory suggests that conservationists are beginning to win the day.

About a mile to the west of Spiegelhalters lies the wonderful enclave known as Norton Folgate, an ungentrified backwater of cobbled streets and shabby warehouses, a stone's throw from Hawksmoor's mighty Christ Church, Spitalfields and the lovely silk weavers' houses in Fournier Street. The developers, British Land, planned a wholesale demolition, retaining some of the fa��ades and erecting behind them the usual corporate glass and steel boxes. Thanks largely to a campaign organized by the Gentle Author (who blogs anonymously, daily, and inimitably, here), Tower Hamlets Council last month rejected the developers' proposals.

If you've never made a perambulation of the district, once home to Christopher Marlowe ��� well, you certainly should. From the Middle Ages until 1900 Norton Folgate was a self-governing "extra-parochial liberty" within the City of London ��� a district in which rights reserved to the king were devolved into private hands. The Liberty of Norton Folgate consisted of around eight acres, now reduced to Folgate Street, Spital Square, Elder Street, Fleur de Lis Street and Blossom Street.

On Folgate Street is a wonderful pub with an evocative name ��� the Water Poet. I went for a drink there recently to celebrate the Spiegelhalter victory and stayed for a couple more. The place is named after John Taylor (1578���1653), who was born in Gloucester but spent much of his life as a Thames waterman, a member of the guild of boatmen that ferried passengers across the River Thames (there was only one bridge at the time). Taylor rose in the hierarchy of the guild to serve as its clerk. In The True Cause of the Watermen's Suit Concerning Players (written c.1613), he wrote about the watermen's disputes with the riverside theatre companies which, in 1612, moved en masse from the south bank to the north, depriving the watermen of their income.

http://www.britannica.com/biography/J...

Taylor was a prolific writer with more than 150 publications in his lifetime, many of which were gathered into the compilation All the Workes of John Taylor the Water Poet (1630; with a facsimile reprint by Scholar Press in 1973). His prose is unpolished but his observations of seventeenth-century London will appeal to social historians.

He was something of a public prankster, undertaking a number of eccentric journeys that were, in effect, crowd-funded conceptual artworks. He travelled from London to Queenborough in Kent in a paper boat with two stockfish tied to canes for oars. In 1618, he walked to Scotland: he took no money with him, but later published an account of his travels in The Pennylesse Pilgrimage; or, the Moneylesse Perambulation of John Taylor, alias the Kings Magesties Water-Poet; How He TRAVAILED on Foot from London to Edenborough in Scotland, Not Carrying any Money To or Fro, Neither Begging, Borrowing, or Asking Meate, Drinke, or Lodging. He had an impressive tally of 1,600 subscribers. When some of them failed to pay up he published A Kicksey Winsey, or, A Lerry Come-Twang, Wherein John Taylor hath satirically suited 800 of his bad debtors, that will not pay him for his return of his Journey from Scotland.

A final claim to fame: Taylor is among the earliest authors to whom a palindrome can be attributed: "Lewd did I live, & evil I did dwel". (That ampersand will irritate the purist.) The London pub that bears his pen-name has a convivial walled beer garden, a perfect place to raise a glass to the shade of the man himself.

August 3, 2015

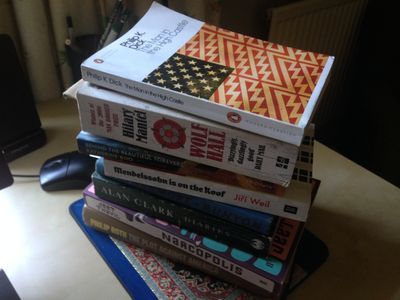

Half-read books

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Half-read books? Don���t you hate them? They sit in piles on your desk or bedside table, gathering dust. Every now and again you brush them down and remind yourself how far you got: ten pages in? halfway? near the end, but you fell on the last lap? Should you try again?

I���ve got two piles��� worth of unfinished books, which suggests a lack of staying power as a reader. Or maybe I���m too easily distracted. Prominent among them is Hilary Mantel���s Wolf Hall, which I simply haven���t been able to get on with ��� I struggled to page 180 or thereabouts a couple of years ago and have remained there ever since ��� my problem, not the novelist���s. I don���t envisage tackling the sequel, Bring Up the Bodies, anytime soon.

Other notable failures on my part include The Plot against America, Philip Roth���s counterfactual novel about Charles Lindbergh winning the US presidency instead of Franklin D. Roosevelt and making a pact with Hitler. It���s very depressing. But I asked for the book as a birthday present so don���t have much excuse for not making great headway. It���s generally thought to be one of Roth���s best.

Roth wrote the introduction to the translation of another novel that defeated me: Ji���� Weil���s Mendelssohn is on the Roof ��� I���d been meaning to read this one for years but when I eventually started it I couldn���t get beyond page 20. And yet I love Czech literature in general. I can���t really explain it. Some books, I guess, just don���t agree with you.

And then there���s Philip K. Dick���s The Man in the High Castle, which I have recently finished. The problem is that I started it in May, so that���s nearly three months to read a 250-page novel, and a really good one at that. Every time I picked it up again I had to go back a couple of pages to remind myself what was happening (in case you���re unfamiliar with it, the book offers another counterfactual: the Allies have lost the Second World War and the Axis powers have taken over the US, with the Nazis in New York and the Japanese in California ��� the book is mostly set in San Francisco). Had I stuck with it uninterruptedly I would undoubtedly have got more out of the book. Maybe I should read it again one day.

Then there���s Narcopolis by Jeet Thayil, set in Mumbai���s drug dens. It���s good, but dense. I got a third of the way through and put it to one side ��� a shame really. Also set in Mumbai is Katherine Boo���s Behind the Beautiful Forevers, about life in a slum. It���s hard-hitting, but very grim; maybe that���s why I put it to one side. Both of these books I will surely resume at some point but I���ve lost something in not sticking with them first time round.

In a different category comes the politician Alan Clark���s Diaries, which was quite entertaining for a while, but ultimately became toxic ��� I simply couldn���t finish it. Maybe I should just put it back on the shelf.

I���m about to set off for a week's holiday and shall choose my reading carefully. I fully intend to finish whatever I start. So no door-stoppers then.

July 31, 2015

In the back of the van

By TOBY LICHTIG

Attending any of the longer theatrical performances at this year's Latitude Festival was nigh on impossible given the accompaniment of a tiny child, but I did manage to catch one excellent and crucially (for my purposes) short piece of theatre, which has stayed with me ever since.

Sweat Box by Chlo�� Moss (directed by Imogen Ashby) takes places in a prison van. (The van, I was told, was requisitioned off some dodgy geezer who does a nice line in them: apparently they make good horse boxes.) There's space for around twelve audience members in the back of the vehicle, pushed up against three tiny locked cells. (We were allowed to inspect the cells afterwards: no seatbelts, barely room to move.) In each cell sits a woman, waiting to be transported to prison. The van has stopped for unknown reasons. The women aren't told what's happening, adding to their sense of frustration . . . .

Over twelve intense minutes, we're treated to the prisoners' repartee, as they reassure and rile one another, and comment on the spectacle of the prison guards, who appear to be standing around outside, flirting and eating sandwiches. One woman is a newbie; she has a toddler at home; she didn't realize she was going be put away earlier that morning and didn't get the chance to say goodbye. Another is a cheerfully cynical old timer. "What's prison like?" the newbie asks. "Butlins", is the reply. The third is pregnant ��� and angry. Only after she emerges, handcuffed, like the rest of them, do we realize how late-term she is. Desperate for the toilet, she has been forced to relieve herself in the little cell. "Lovely", says the disgusted officer, leading her away. The banter between the women is funny, troubling and above all very human ��� the reaction of the officer is, by contrast, degrading.

Clean Break is a theatre charity dedicated to highlighting the difficulties faced by women caught up in the criminal justice system. Sweat Box shows how easy it is to dehumanize those who have had their freedoms removed, for whatever reason, and how it is the little ��� and entirely avoidable ��� humiliations that can be the most corrosive. At a time when Michael Gove is planning to overhaul the criminal justice system, it casts salient light on that tired old debate about rehabilitation vs retribution.

July 30, 2015

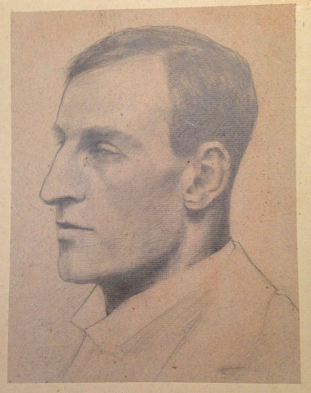

George Calderon and the blog-biography

George Calderon by William Rothenstein

By MICHAEL CAINES

Last September, I blogged about a blog ��� Patrick Miles's Calderonia. Now Calderonia has drawn to a necessary close: its purpose has been to trace events of a century ago, from day to day, through the last year of a man's life.

The man in question is the Edwardian playwright, translator of Chekhov and notable early TLS reviewer George Calderon, who volunteered to fight in the First World War, and was killed in action at Gallipoli in early June 1915. I've been following Calderonia irregularly over the past year, but missed out on the recent posts. Now I see it has become not only the means for making fortuitous discoveries about Calderon, but also a meditation on writing a biography. It has become a biographer's autobiography. . . .

As somebody who only posts the occasional squib or diatribe, I'm in awe of those who stick to a daily (and in this case scholarly) regime. There have been painstaking posts, for example, about subjects such as the likely circumstances of Calderon's death in battle (all the time in the awareness that he didn't "need" to go to war at all, on account of his age). Sticking to the exact chronology of events means recording that Calderon's wife, Kittie, received two letters from him four days later.

Then there is the excitement of discovering a post-war letter from Kittie about George and their friend Percy Lubbock's book about him. And a taste of the literary times in Calderon's dig at A. E. Housman, recalled by the painter William Rothenstein: "Well, William, so far from believing that man wrote A Shropshire Lad, I shouldn���t even have thought him capable of reading it!" (See above for Rothenstein's fine pencil portrait of Calderon, identified by Miles earlier this year.)

Boris Johnson (or at least the ghost of Boris Johnson) has barely a year in which to write a Life of Shakespeare. Patrick Miles first studied George and Kittie's papers some thirty years ago, and has come back to them in earnest over the past five. The blogging has happened in tandem with writing a biography of Calderon. And it has had a potentially productive pitfall: "chronotopia", a tension between keeping a tightly focused day-by-day record and thinking about the long-term, joined-up narrative, too. Blog-time and biography-time eventually got out of sync. And this is how Calderonia has become a biography in its own right.

"Both for me and, I know, some followers", Miles says of the past year's virtual life-writing, "it also seems an eternity because we have lived through it all day by day":

"Somewhere, I believe, Carl Jung said that the present is ���terrible in the intensity of its ambivalence���. Rather like one���s own life, so many of the days of this blog have been intense with that ambivalence that I can no longer remember them all; the relevant brain cells have apparently been seared out; I cannot possibly now get my memory round the whole of this blog-year���s events."

One of those memories will be about the general challenge of biographical writing, as in this post, a critical response to Ruth Scurr's salutary Guardian essay about biography and her novel approach to writing a biographer's biography. Is biography, as strictly defined here, flourishing today ��� or is it "almost at a standstill"? For some, we are living through a new golden age, albeit one too heavily gilded with Shakespeare biographies; others, I suspect, are sceptical about attempts to escape from the plod of the cradle-to-grave approach. (Don't we still rely on them, despite the insights and gains of books about Peacock Dinners or Nights at the Majestic? And anyway, aren't such "momentary" accounts just following in the wake of the immortal joy that is Alethea Hayter's A Sultry Month?)

Golden age or not, though, the problem remains the same: in Scurr's words, "how to find a narrative form that fits the life (or lives) in question". In George Calderon's case, maybe there are two forms that fit. I wonder who is next for the blog-biography treatment.

July 28, 2015

At the back of the tent

By TOBY LICHTIG

Even to the hardiest of campers the modern British music festival contains its share of obstacles (sunburn or trenchfoot, depending on conditions; traffic reminiscent of Jean-Luc Godard's Week End), so the decision to bring our ten-week-old daughter to Latitude this month was not taken lightly.

Days of planning and buying (miniature ear defenders, an electric fan for the car) segued into hours of congestion on the A12, screaming infantile discomfort and an error of topographical judgement that led to an hour-long trek around the perimeter fence. As we finally acquired our wristbands and entered the site, it was impossible to ignore the uncomfortable question: would it all be worth it?

Fortunately it was. Latitude is about as child friendly as big festivals get, and, along with beautiful scenery ��� woods; a punting lake ��� there was plenty for tiny eyes to marvel at, not least the sheep sprayed a psychedelic pink (washable dye, we were assured). Babies can simplify as well as complicate things, and our options this year were fairly limited: no loud music (the ear defenders proved to be too large), no big crowds, somewhere with space to lay out the changing mat. What better areas to camp out in than the back of the Literature and Poetry tents?

The programme was very varied ��� which meant bad as well as good; and yet the curators can partly be forgiven for holes in the literary line-up. This isn't Hay or Cheltenham and there's little point in inviting a wide array of major names from the book world when they also have to compete with Portishead and Thom Yorke. (With this in mind, perhaps there could have been more focus on the experimental, the challenging; and I'd have liked to see more genuine debates than cosy book promotions or fully consensual discussions.)

The theme for the weekend was "For Richer for Poorer for Better for Worse", and a host of the usual suspects (Owen Jones, Georgia Gould) were there to give their views on what's happened to Britain's Left (the most convincing argument: it has forgotten how to play hard politics). An environmental strand also ran through the weekend, with Patrick Barkham speaking eloquently on coastal erosion and Blake Morrison providing his own take on local environmental degradation in poems from his most recent collection The Ballad of Shingle Street. In the title poem, which was first published in the TLS, memories of Nazi invasion in 1940 ("And in the dusk they tell a tale / Of burning boats and blistered flesh") mingle with an apprehension of more recent natural threats: "The waves maraud, / The winds oppress, / The earth can't help / But acquiesce". Shingle Street is about an hour's drive from Henham Park in Suffolk, where Latitude is based, and even nearer is Dunwich, the scene of another of Morrison's Suffolk coast poems. "The Discipline of Dogs" tells the tale of a woman who feeds her beloved mutt an ice-cream at Dunwich Beach, "its tongue neatly curling to detach / the twirly flourish at the tip": an image that caused a ripple of amusement around the tent.

Along with some pretty effective beatboxing, some rather abject cabaret, and a bizarre if spirited adaptation of the works of Virginia Woolf to the music of Benjamin Britten (perhaps I was distracted by the baby but it was pretty hard to work out what was going on), I enjoyed Eimear McBride in conversation with Anita Sethi. McBride again told the well-known tale of the provenance of her prize-winning novel A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing, but she also provided some fascinating insights into her development as a writer. A Joycean commute in London was one crucial factor: "I got on with Ulysses at Bruce Grove and by the time I reached Liverpool Street I knew that everything I ever knew about the novel had changed forever". The influence of the playwright Sarah Kane was another: "I had previously thought that women weren't allowed to be angry in prose". McBride also argued that, despite its debt to modernism, her style is a direct reaction to the contemporary world: "In the age of the internet the novel has a different job"; no longer concerned with imparting information, "it has to be boiled down to its most essential self". "I wanted to take the writer out of the reading experience . . . to make it completely unmediated."

Mediation is John Crace's stock in trade; style, to him, is everything ��� that is, other people's style. Crace is well-known for his Guardian "digested reads" in which authors are cruelly and amusingly mimicked. He hasn't yet taken on McBride ��� he never tackles debut writers ��� but given the idiosyncrasies of the Irish author's voice it is perhaps only a matter of time. At Latitude, the targets of Crace's mimicry included Lady Antonia Fraser and her admiration for the poems of her husband "Herald" (sample, via Crace: "Your radiance divine / Is mine all mine"). Despite being "so very heppy", Crace's Antonia spared a thought for the misery of others around the dinner party table ("Salman was also present. His fatwa is too too awful"). Stepping out of role, the author commented on the unfortunate irony that Antonia "submitted herself to Harold's happiness, and it was clear that Harold was the grumpiest bastard around". The memoir of Fran��ois Hollande's former mistress, Val��rie Trierweiler, delivered by Crace in a ludicrous franglais, provided another amusing butt ("It was toucher et aller whether I would survive") and Crace's "digested read digested" for Harper Lee was both topical and succinct: "To kill a golden goose".

Crace is also the Guardian's parliamentary sketch writer, having succeeded the late Simon Hoggart, and he answered questions about the current Labour leadership contest, apparently unequivocal about his favoured choice. "I'm certain the person David Cameron would least like to face is Yvette Cooper". Who will win remains anybody's guess ��� Crace also spoke about the failure of pollsters and pundits at the most recent election ��� but with Labour currently in tatters, it will be interesting to see whether commentators at next year's Latitude will be able to take a more positive view of Britain's flagging Left.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers