Peter Stothard's Blog, page 25

May 22, 2015

Girl, interpreted

Aoife Duffin; photographed by Richie Gilligan

By DAVID COLLARD

The highlight of this year's Norfolk and Norwich Festival was the English premiere of Annie Ryan's stage adaptation of A Girl is a Half-formed Thing, Eimear McBride's debut novel.

The 300-seat Playhouse Theatre was a particularly appropriate venue because Norwich is home to the independent Galley Beggar Press, publishers of the novel in 2013. Over the subsequent months it went on to win just about every literary prize: the Goldsmiths, the Baileys (formerly Orange), the Kerry, the Geoffrey Faber and the Desmond Elliott. This spectacular haul was all the more surprising because A Girl is a Half-formed Thing is quite unlike the heavyweight middlebrow writing that dominates most shortlists.

Before going on I should declare an interest. I wrote the first ever review of the novel (for the TLS) and have just completed a monograph on the author and her work (with emphasis on the latter).

I'd been invited by the festival organisers to chair a post-show discussion following the second performance in the play���s short run, and was joined on stage by the director, the author and (later) the solo performer, Aoife Duffin (of whom more in a moment).

The Chicago-born Ryan, founder of Dublin's Corn Exchange Theatre, had her work cut out in adapting it for performance. Her version runs for a brisk eighty minutes, cutting around 85 per cent of the original text. The audiobook version of A Girl is a Half-formed Thing ��� read superbly by the author ��� lasts for seven-and-a-half hours and there's not a line that's easily lost, not a word.

In our discussion Ryan recalled telling the author at the outset that she thought the novel was performable, but not necessarily stageable (a nice distinction). The author imposed the challenging condition that the audience should not see the girl, because everything in the book is experienced from her perspective. Although constantly subject to a predatory male gaze, the nameless girl is never described. There's no mediating authorial presence and the reader experiences with startling directness everything that happens to the girl. Many of these things are terrible, and that is what makes the novel so emotionally overwhelming.

Arriving at a pared-down script after many drafts and re-drafts, the next great challenge was to find a performer who could be present on a bare stage yet remain effectively invisible. Ryan already had an actor in mind, and her casting was inspired.

The extraordinary Aoife Duffin gave one of the most powerful theatrical performances I've ever seen, Thirty years old and slightly built, she portrayed the girl as a foetus (briefly), then as a newborn baby, toddler, gauche teen and troubled young woman ��� a whole lifetime. She also played every other character with virtuosity: the mother (particularly impressive), the dying brother, the bigot grandfather, the predatory uncle, a bunch of callous schoolboys, university students, gormless evangelical Christians and others, many others. This was a superb display of physical acting ��� subtle, detailed and constantly inventive, enriched by her distinctive Kerry accent, by turns soft and grating. It was a gruelling experience for both Duffin and her audience, and I was reminded of Billie Whitelaw directed by Beckett in Not I.

In the post-show talk McBride, who studied theatre at Drama Centre in London, described her approach as ���method writing��� and we explored, briefly, the overlap between Stanislavskian approaches to acting and writing. We were later joined by Duffin (greeted with a burst of applause) and the discussion continued with many illuminating insights into the genesis of the production and the travails of rehearsal. I listened in a slight daze, unable to detach myself from the intense experience of the previous eighty minutes. When I saw the show again the following night it was, if anything, even more powerful. Like the novel, it has a momentous presence. Unlike the novel, the play is a collective experience.

A Girl is a Half-formed Thing recently appeared in Dutch translation as Een meisje is maar half af and will be published in French next month, with other translations to follow. Also next month the author will be reading, for the first time in public, passages from her forthcoming second novel, The Lesser Bohemians, due for publication next year. Before that keenly-awaited event the Corn Exchange production will be visiting other venues in Britain and is not to be missed.

May 21, 2015

Scandi design genius

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

We���ve all become familiar with the concept of Scandi noir. But let���s not forget Scandi design, something else for which the Nordic countries seem to have an especial talent ��� and I���m not just talking of the crowd-pleasers Ikea.

The Times earlier this week ran an obituary of Jacob Jensen (below), who has died at the age of eighty-nine. Jensen was a designer who worked for the Danish firm of upmarket manufacturers of music systems, Bang & Olufsen ��� ���By appointment to the Royal Danish Court���. The obituarist described Jensen as ���arguably the greatest exponent of Scandinavian slick-tech���, which is nicely put.

Speaking as one who inherited a 1970s Bang & Olufsen music system I can concur. They are things of beauty (and I regret that I simply don���t have the space at home to set it up; there it sits in the loft, unused, for me to occasionally go and gaze at and purr with pleasure). The combination of wood with a black metal front (dazzlingly lit up when switched on) is striking in its simplicity; minimalism as an art form (as in the image at the top of this post).

But Jensen didn���t just design hi-fi systems. ���Over half a century, [he] would design more than 500 products in his Jutland retreat, including the first touch-button telephone . . . which has been cited as a timeless, and much plagiarised, design classic.��� I���m thinking also of his alarm clocks ��� simple, utilitarian objects, but beautiful too.

An interesting fact Jensen���s obit revealed was that the Nazis burnt down the Bang & Olufsen factory ���in an act of revenge because of its refusal to co-operate with the occupiers���. The factory was rebuilt after the war, initially producing electric razors before moving on to more sophisticated products.

I sense that the hi-fi systems the firm brings out now are too minimalist and space-age to please the eye to the same extent, as well as no doubt being eye-wateringly expensive ��� I've only looked briefly. Maybe the 70s were Bang & Olufsen���s heyday. Either way, I feel very fortunate to have one.

May 19, 2015

Shakespeare, naturally

By MICHAEL CAINES

Is Country Life in any danger of selling out in the university towns this week? In its latest issue, the magazine is revealing what it is calling the "true face of Shakespeare": "an astonishing new image of William Shakespeare, the first and only known demonstrably authentic portrait . . . made in his lifetime".

Cue the traditional overtures of over-excitement from the newspapers and the sceptical/envious/infuriated/perplexed reactions from the professional Shakespeareans. . . .

They have, of course, heard stories before of Shakespeare's "true face" (in which people seem to take an inordinate interest, rather like that of Jane Austen). Searches for that face that claim to have found what they were looking for often reveal nothing more than our fantasies of what a great writer looks like.

"Isn't such a search doomed to disappointment and failure?", Katherine Duncan-Jones has asked in the TLS. "After all, he was not a Romantic poet who made his art out of his own subjective experience, cultivating his personal image and appearance in the manner of Shelley or Byron." (There's so much to blame the Romantics for.) Yet do forgive yourself if some line about hope and how it springs comes to mind at this point.

The image above is the title page of The Herball, John Gerard's vast and vastly expensive folio "Generall Historie of Plantes", published in 1597. (Apologies for the quality of the reproduction. No doubt better ones will soon make themselves freely available online. Other title pages for the book are from later impressions/editions.)

The four fellows depicted on the title-page above have been dismissed as generic or allegorical. When the botanist and historian Mark Griffiths started work on a biography of Gerard ten years ago, he wasn't looking to identify them with real people. Eventually, however, he identified three of the figures: Gerard himself; his Flemish peer Rembert Dodoens; and William Cecil, Lord Burghley, the great statesman who employed Gerard as his Garden Superintendent. Who was the fourth man?

His story is an intricate affair, and buying the idea that he is Shakespeare depends on evidence that I won't go into in full here, not wishing to misrepresent a case that I've only heard in detailed yet abbreviated form during a press briefing held this morning at the Rose Playhouse (just down the river from TLS HQ). Whether people agree with it or not, it's clearly an intricate and responsible piece of work, cautiously shared between only a few experts for the past five years. Griffiths's case rests partly on the kind of Elizabethan cipher game that literary scholars seem to dislike intensely, especially as they've been used to support all manner of eccentric theories over the years.

Yet I admit I'm taken with one detail, the presence of a certain flower in "Shakespeare"'s hand: it's a snake-head fritillary, apparently, not seen in the wild in Britain until 1796, but known to Gerard in 1597: "They are greately esteemed for the beautifieng of our gardens and the bosomes of the beautifull", he wrote. To Shakespeare, they mattered, too: in Venus and Adonis, published a few years before The Herball, he has the blood of that "rose-cheek'd" victim of Venus fall to the ground and give rise to a "purple flower . . . chequer'd with white".

That would seem to be a deliberate diversion from Ovidian tradition, in which it is the anemone that springs from Adonis's blood ��� a slight adjustment, perhaps, since anemones can be purple, too. But variegated, "chequer'd with white"? As Miriam Jackson recently argued in Barbarous Antiquity, here is one way in which Shakespeare perhaps shows he wishes to transform the myth into "something entirely new" ��� by turning Adonis into an "exotic bulb, whether a fritillary or a variegated tulip", he wishes to "generate literary currency" much as exotic new bulbs did in the same period.

No doubt we'll hear more arguments and counter-arguments about all this soon, cynicism straining as far in one direction as naivety will strain in the other. This kind of thing often gets an adverse reaction and often deserves it. While the TLS letters page carries on in its stormy way with a debate about what Shakespeare did or didn't write around the same stage in his career, Griffiths is clearly in for an interesting time among the Shakespeare experts. I'll just second-guess one further dubious implication of this latest "portrait" ��� of a rather classicized chap with a full head of hair.

For Griffiths (a Fellow of the Linnean Society and a regular contributor to Country Life) and his (medievalist) collaborator Edward Wilson, a Fellow of Worcester College, Oxford, have already stated their intention of editing what they suspect to be Shakespeare's verse contributions to The Herball ��� something that would partly explain, I suppose, his presence on the title-page in the first place. (They'll also no doubt enrage various scholars by suggesting that, at the time, Shakespeare was effectively Burghley's pet propagandist.)

Is this one of those contributions? It's not a translated snippet from the Latin, as most of them must be, but a poem of "commendation" by "W. Westerman", a name that might cause some to get carried away, hyperbolize and imagine that they've found Shakespeare, a "W" for William from the West, working under an obvious (but unnecessary?) pseudonym. The poem is, in fact, in the same stanza form as The Rape of Lucrece:

Not bad, is it? No doubt a machine could subject it to the usual sort of analysis and tell you how closely it corresponds in various ways to the canonical Shakespeare. But that stanza form is also a formerly fashionable stanza form, rhyme royal, and, inconveniently, a contemporary William Westerman who wrote sermons and poetry did exist. Something always has to be explained away, I think, in attribution studies, when something else is put in its place.

Independently but inconclusively, Gerard has been linked to Shakespeare. And I'm not sure if it's completely implausible, if unpalatable to some, that Shakespeare the poet of nature was also an "upstart crow" and a crony of Cecil's. Inevitably, though, people read more into it than is reasonable, o'erleaping evidence in their desperation to touch the hem of Shakespeare's garment. On the basis of the findings Country Life promises to publish this week and next ��� which include, by the way, "a new play by Shakespeare" ��� I'm looking forward to seeing the dubious penumbra of the Shakespeare canon growing a little wider, yet again.

May 17, 2015

Peter Pi��t'anek remembered

Peter Pi��t'anek, 2014; (c) SME

By DONALD RAYFIELD

Peter Pi��t'anek, the finest of modern Slovak novelists, died of a drug overdose on March 22, just before his fifty-fifth birthday. I discovered his work ten years ago, as an external examiner for Rajendra Chitnis���s doctorate on Slovak prose. I was duty-bound to read the Pi��t'anek works Chitnis discussed: I rolled on the floor, helpless with laughter. Pi��t'anek���s irreverence, obscenity, wit and ingenuity would, I was sure, find a British publisher. After a year���s wait I gave up, wrote to Pi��t'anek and found a translator, Peter Petro, who shared Pi��t'anek���s own background in Bratislava���s semi-dissident demimonde, and his mix of languages (Viennese German, Hungarian and even Romany enrich Bratislava Slovak). We then published his most striking novel Rivers of Babylon and its two sequels with the Garnett Press.

No one has evoked so well Eastern Europe in the late 1980s, when thugs and secret policemen metamorphozed into racketeers and ���businessmen of the year���. Pi��t'anek portrayed sex and violence as graphically as a manga novelist and as convincingly as if he had experienced every sado-masochistic ploy of his anti-heroes. Yet when he came to London to launch Rivers of Babylon at Foyles, despite an endearing resemblance to Uncle Fester of the Addams family, he was all charm and self-deprecation. For all his dark satire, he was a reticent man, but with an uproarious sense of humour.

His passion in London was not literary, but for a rare Spanish brandy, traced to a stockist in Ealing. His literary admirers found that he was an expert in Scotch whisky and had visited every distillery in the Highlands and islands. Even a successful Slovak novelist can���t sell enough books to make a comfortable living: Pi��t'anek made his main anti-hero R��cz an enthusiastic brandy and whisky drinker, so the Bratislava distributors for Hennessy, R��my-Martin and Macallan happily paid for placement with crates of their products. Food, unimportant to his heroes, was a preoccupation for Pi��t'anek: if his book, Recipes from the Family Archive, finds an English publisher, his study of brandies will prove as appealing as his fiction.

Pi��t'anek was in Communist days a drummer in a rock group (a life he celebrated in his novella The Musicians): this was then one of the few careers that allowed young Slovaks to travel abroad, if only to Bulgaria. Becoming a writer was harder, even after the Velvet Revolution. Pi��t'anek���s exposure of the underbelly of Slovak life and his satire on sacred Slovak pretensions (which he called ���narcissism���) caused a scandal. His novellas sympathized with the underdog: in the Young D��n��, he offended patriotic readers by taking as his hero not the wise beekeepers and chaste maidens of conventional Slovak novelists, but rather, a subnormal child of alcoholic peasants who spends his first wage on a Bratislava whore. Pi��t'anek���s genius became manifest in Rivers of Babylon which, with its sequels The Wooden Village and The End of Freddy, formed a trilogy in which the thug who takes over the money-changing and prostitution rackets in a hotel transmutes into an oil oligarch. Pi��t'anek���s plotting has the ingenuity of Quentin Tarantino, the irony of Evelyn Waugh and, in the later novels, an obscenity that makes Last Exit to Brooklyn seem mealy-mouthed.

The third novel, The End of Freddy, showed another side to Pi��t'anek, who wrote in Czech whenever the novel���s action moved to Prague. Slovaks always felt like the underdogs in Czechoslovakia; although the two languages are mutually intelligible, Slovak films used to be subtitled for Czechs, while Slovaks had to watch Czech films without assistance. This homage to the Czech language provoked Pi��t'anek���s readers as much as his low-life characters did. Pi��t'anek loved to torment authority: his scurrilous trilogy of Tales about Vlad were such a thorn in the flesh of Vladim��r Me��iar, the Slovak prime minister, that nobody would have been surprised if the author had been drowned in the Danube.

Rivers of Babylon has now been translated into several European and Asian languages. Pi��t'anek was beginning to get, via the English versions of his novels, an international reputation; the Slovaks, more sophisticated with every year, came to value their enfant terrible. Pi��t'anek was full of plans: a fourth novel in the Rivers of Babylon series, in which the terrifying R��cz would lust after an aristocratic title and plot to get it by murdering his former enemy, the newly restored Hungarian Count Feri (after becoming the count���s adopted son). Pi��t'anek���s own childhood was reflected in the childhood of his other unsavoury hero, the car-park attendant and pornographer Freddy Piggybank: he planned to expand on this with an autobiographical novel about growing up in a brickworks to the sound of locomotives.

A decade ago Pi��t'anek���s now defunct online magazine and radio programmes won him fans half his age: they have grown up to be his most appreciative readers. Pi��t'anek recently published a new novel, The Hostage, which was to be adapted for film. His marginalization seemed over. But the depression that plagued him returned.

May 14, 2015

Rediscovering Brigid Brophy

By MICHAEL CAINES

A few years ago, the Observer published a sublimely wayward list of Britain's "top" 300 intellectuals. Here one learned that the little-known Indian economist Amartya Sen and even lesser-known Irish poet Seamus Heaney were British, while one writer was included whose death in 1995 apparently presented no obstacle to her cutting a "public figure" in 2011: the restlessly inventive novelist and campaigner for author and animal rights alike, Brigid Brophy.

Now it's twenty years since Brophy died, and it still remains fair to say that she deserves wider recognition. But that's not exactly saying anything new . . .

That is: people have been saying something like that since at least the 1980s. Apparently, they would ask Giles Gordon, her literary agent, "Whatever became of Brigid Brophy?" ��� and the "terrible answer" he would give was that multiple sclerosis had been, for many years, making her life "pretty much hell".

And what made them ask in the first place? Apart from anything else: her campaigns for Public Lending Right, and against laboratory vivisections; the Shavian sharpness of her journalism; and her books, each one of which was a virtuosic left turn from the last.

Born in 1929, sent down from Oxford, and recognized as a promising literary talent in her twenties, the Anglo-Irish Brophy became an unmistakable critical voice in the early 1960s, partly by remaining true to some distinctively unfashionable sources of inspiration. She expressed heretical views about religious education, open marriage (she had one, to Michael Levey, director of the National Gallery) and lawn tennis, while maintaining that the two most fascinating subjects in the world were "sex and the eighteenth century". She could be forthright, outspoken, acerbic, or whatever word her opponents could find for her ��� in the TLS, Ian Hamilton (sheltered by anonymity, of course) called her "one of our leading literary shrews".

Yet that period of modest notoriety disguises the fact that her tastes were not entirely "of" the 1960s. Baroque-minded and classically educated, Brophy said that one early story, "Late Afternoon of a Faun", originated in a Latin class. She was in favour of Ronald Firbank and against the crudeness of Lucky Jim; highly pleasurable comments on the first and excoriating remarks on the second may be found in the memorable volume of "views and reviews" pictured above.

After GBS, she called a story collection The Adventures of God in His Search for the Black Girl, which captures her versatility in a single volume. Here are paradoxes that remain all too piquant ("'Poverty is a crime,' the sage said, 'but it isn't the poor who are guilty of it.'"), one-liners ("'I'm afraid we shall have to make a small charge.' said the cavalry commander."), a straight-faced account of Ambrose Bierce outlasting his natural span of years and adopting the pseudonym Jorge Luis Borges, as well as the Platonic dialogue of the title, between God, Voltaire, Edward Gibbon and a few others. "I didn't ask for a whitewash job", Brophy has this supreme deity say of his depictions in art and literature, "Indeed, without self-flattery, I think I'm the ideal romantic-opera hero. It leaps to the eye. You have only to consider my moodiness, my sudden but inexorable anger and my frequent obstinate silences when addressed."

Much of Brophy's fiction has been reissued over the past two decades, including Hackenfeller's Ape, her spry debut of 1953, the "heroi-cyclic" In Transit and The Finishing Touch, a Firbankian acid drop of a novel, in which she transmogrifies Anthony Blunt into the headmistress of an institution on the French Riviera. There have been further welcome reissues in the past few years from Faber Finds and the Coelacanth Press.

I'm not expecting a reissue of a work of non-fiction such as Black Ship to Hell any time soon ��� that one's a lengthy, Freudian meditation on art, violence and civilization ��� but it would be wilful philistinism to ignore her collections of journalism. You know you are in the presence of a properly decided, opinion-pinioning mind when you read an essay that begins: "The three greatest novels of the twentieth century are The Golden Bowl by Henry James, A la Recherche du Temps Perdu by Marcel Proust and Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli by Ronald Firbank". Showing she meant what she said, Brophy went on to write a full-length "defence of fiction" in the guise of Prancing Novelist: In praise of Ronald Firbank.

There are signs that people are rediscovering the argument that Brophy needs rediscovering. Hunt around in the usual online ways, and you will find fresh acknowledgements of In Transit and the seminal contribution of The Rights of Animals. You may come across the website Discovering Brigid Brophy, where Brophy's daughter Kate Levey offers, among other things, reminiscences about her childhood home (most of which was given over to a kind of "private literary den"). The novelist Jonathan Gibbs has written warmly about Flesh, which features a different kind of gender swap from The Finishing Touch: it's Brophy's contemporary retelling of the Pygmalion myth, in which it is a woman who fattens up her husband and turns him into, as he himself jokes, a "Rubens woman".

And there's to be a Brigid Brophy conference in October, when the speakers will include Peter Parker and Philip Hensher. It sounds like I have to go, doesn't it? I'm looking forward to finding out more about this most mischievous of literary shrews, and the well-wrought range of her achievements.

May 13, 2015

The Alice look

Mia Wasikowska in Tim Burton's Alice in Wonderland (2010). Photo: Moviestore/REX Shutterstock

Mia Wasikowska in Tim Burton's Alice in Wonderland (2010). Photo: Moviestore/REX Shutterstock

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

A white pinafore, blue dress, strapped shoes, stockings, headband, bare arms and blonde hair ��� the image of Lewis Carroll���s Alice has been stamped ineffaceably in our minds ever since Alice���s Adventures in Wonderland was first published 150 years ago. It was then that John Tenniel���s magical, potent illustrations put her in a typical middle-class Victorian girl���s dress ��� an original of which is now on display at the V&A Museum of Childhood���s new exhibition, The Alice Look.

When Tenniel eventually coloured his black-and-white drawings, however, Alice���s dress was yellow; it was only much later, after his death in 1914, that she was given a blue one, and it's probably Disney���s success ��� first with the animated film version of 1951 (not forgetting a short film in 1923), then its Tim Burton-ized update in 2010 ��� which has made this her most recognizable form . . . .

It's remarkable that this small exhibition manages to show how illustrations of Alice have evolved with contemporary fashion. As she says herself: ���it's no use going back to yesterday, because I was a different person then���. In a rare edition of the book from the 1920s, Alice has a bob haircut and wears a dropped-waist white dress; a polka-dot red swing skirt in the 1950s (Yayoi Kusama���s trippy artwork, and as it happens her illustrated Alice in 2012, surely stems from this); and in an edition from the 1990s, Pixie O���Harris draws her in blue jeans and a t-shirt.

Alice���s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll. Illustrations by John Tenniel (1900s). V&A Museum London

Alice���s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll. Illustrations by John Tenniel (1900s). V&A Museum London

Is it a surprise that her style is often localized, too? (Alice has been translated into 170 languages.) In a Swahili edition published in 1940, she swaps her crinoline and linen dress for a striped kanga; in Proven��al she���s pictured wearing a simple sundress and trop��zienne leather sandals. A couple of weeks ago, Michael Caines wrote about Franciszka Themerson ��� an artist, filmmaker and founder of the Gaberbocchus Press ��� who drew Alice in a long dress, wandering through ���Wonderland��� in 1942; tanks, mechanical figures and a heavy sky loom in the background. Vivienne Westwood is the latest to design an Alice: her cover and endpapers for the Vintage Classics��� anniversary edition incorporate Tenniel���s original illustrations with geometric blocks of colour and a ���Climate Map���. She writes in her introduction: ���Never be complacent. The world we think we know reflects the way we are conditioned to see it. Maybe it���s not like that at all. Carroll is on your side. Always wonder���.

The counter-cultural fashion movements in Britain in the 1960s and 70s took inspiration from Carroll and Tenniel���s creation. A monochrome poster from the V&A���s archive advertises T. Elliott & Sons���s ���Alice Boots��� (���5 & 6 gns���). The bewitching illustration ��� a pastiche of Aubrey Beardsley ��� depicts a woman in lace-up boots clutching flowers in her bell-sleeved arms. Tumbling around her in the shadows are peculiar, Hieronymus Bosch-type figures with pointy demon ears, amorphous skulls and masks. Over in Japan, more recently, street style has appropriated the Alice uniform, stepping up the Victoriana with excessive ribbons and lace: an outfit from 2011 on display is completed with a fluffy black dog handbag. And a photograph of Grayson Perry in a blue "Alice" frock, holding a mini-Alice doll, is an inevitable supplement at this point.

Japanese street fashion outside the National Gallery, Trafalgar Square, London, March 22, 2014. Photo: Johnny Armstead/Alamy Live News

Japanese street fashion outside the National Gallery, Trafalgar Square, London, March 22, 2014. Photo: Johnny Armstead/Alamy Live News

The exhibition doesn���t ignore the darker, more uncomfortable side of all this, which is ��� most decidedly ��� not for kids (though it does bypass whether or not Carroll���s liking for children was simply an innocuous affection, which Dinah Birch discusses in her review of Robert Douglas-Fairhurst���s The Story of Alice: Lewis Carroll and the secret history of wonderland in this week���s TLS ��� subscribers can read it here). GQ���s ���Malice in Wonderland��� (2000) photo-shoot shows us what happens when "hedonistic fashion faces meet for tea": Jade Jagger is dressed as a sexy Cheshire Cat, Philip Treacy is the Mad Hatter and Kate Moss is the White Rabbit.

No doubt we'll see further variations on Tenniel's theme as the Alice hysteria rises this year. After all, as the changeable Duchess advises: ���Be what you would seem to be ��� or, if you���d like it put more simply ��� never imagine yourself not to be otherwise than what it might appear to others that what you were or might have been was not otherwise than what you had been would have appeared to them to be otherwise���. Well, quite.

May 11, 2015

Infinite riches in little rooms

By MICHAEL CAINES

You���re probably asking yourself ��� and if not now, maybe you will later, as you dawdle down the street, enjoying the warm weather (I���m assuming too much about you, I know) ��� what the devil���s going on with the little/literary magazines of this world? Should you be reading one? Are there new ones worth a first look or old ones worth a second?

Here's how I'd answer such questions, in the form of my own notes from happily reading some of the recent issues of various magazines that have caught my eye. . . .

Out of desperation or pride, the London Magazine clings to the notion that venerability is its strongest selling point. ���First published in 1732���, proclaims the front cover. The eighteenth-century London Magazine has a few things in common with the current version, although the original was a vehicle for anti-Tory sentiment and ceased publication in 1785. Its modern counterpart began in 1954 under the editorship of John Lehmann, although it is indelibly Alan Ross with whom many will associate the name. It is now owned by a Tory, but is apparently more ���eclectic��� in its coverage.

The April/May 2015 issue has an elegiac side: Grevel Lindop mourns the passing of the ���age of letter-writing��� (���Future biographers will have a problem���); a series called ���My London��� continues with Suzi Feay���s imagined dividing of the city after a break-up (���Soho���s streets we must re-order / I���ll take Berwick, Greek and Wardour���). And then there���s Edward Lucie-Smith, on fine ranting form, writing about the ���demise of art criticism���, and an encounter with a publisher who wants him and his co-author to do all the work, ���without a cent of investment on their part���. More generally, Lucie-Smith suggests, the web is partly responsible for the decline of the expensive art book. "The Demise of Art Criticism" can be read for free on the London Magazine website.

Now might be a good time to turn back, if you have a copy, to the Spring 2015 issue of the Dublin Review, and Ian Sansom���s diary for 2014, ���Crying into the Emulsion���. Partly for the amusing notes on the writing life ��� the early rising to write two novels in twelve months, the familiar faces at a London book launch (���Craig Raine, Christopher Reid, weird people from the TLS, young fat ugly men, young slim good-looking women . . .���) ��� but also for the September 19 entry, in the wake of the Scottish referendum: ���over breakfast my wife . . . explains to me some of the possible implications for Northern Ireland, and next year���s UK general election: rise of minority parties, UKIP, et cetera, another coalition government dominated by the Tories. Multiple versions of awfulness���.

Out of Dublin also comes The Stinging Fly, on a mission ���to seek out, publish and promote the very best new Irish and international writing���. There are some splendid examples of the Fly succeeding in this mission in their Spring 2015 issue (as there are in Colin Barrett's Fly-supported, award-winning story collection Young Skins), which includes Colm Breathnach���s ���Muirdhreach��� (���Seascape���, presented in facing-page Irish and Marit Howard���s English translation) and Nicole Flattery���s debut, ���Hump��� (���The men continued to stare at me like I was an item of significant interest���), which reads to me like Grace Paley stuck in an office (and an office romance barely worthy of the name). The issue opens with Sara Baume���s ���Eat or Be Eaten: An incomplete survey of literary dogs���. The survivalist's challenge in the title comes from Jack London: ���he didn���t dare rose-tint the base preoccupations of his beast characters, instead celebrating their beast qualities over and above their propensity to be humanlike���. And Baume, whose first novel Spill Simmer Falter Wither is a ���Dog Book���, is well-placed to appreciate the unsentimental side of White Fang: ���I spend significantly more time with animals than I do with people���.

Two more (for now), and then I���m done. Shooter Literary Magazine is a biannual (not biennial), edited by Melanie White. It takes printed form safe in the knowledge that, as one wise man of the wired-up world acknowledged, ���extraordinary content is going to stay in the print domain���. For me, the extraordinary high point of Shooter���s Winter 2015 issue is Corey Pein���s ���Women and Children First���, perhaps because, reading the magazine straight through rather than dropping in here and there, I imagine it sounds a note of non-fiction authenticity after two (perfectly effective) short stories and a poem. It���s one of those pieces that begins quietly, with a ���routine���: the author, a journalist, cycling over from the office of a Santa Fe newspaper to the courthouse. For a couple of years, Pein concentrates on reading the files marked ���CV��� (civil lawsuits) and ���CR��� (criminal complaints). Then he starts in on the files pertaining to acts of domestic violence. ���I figured the best thing that could happen to most of the people I read about in the DV files was that I never saw their names again.���

Open the thick Lent 2015 volume of the Cambridge Literary Review at random and you might come across an item excluded from the contents list. ���The Gissing Link��� ends: ���Will you select the contemporary popular novel that was the purpose of your visit? If so, turn to page 163. If you think you would do better to select something impressive and improving ��� possibly even scientific ��� turn to page 102���. I don���t know if this is the first time a journal has come laced with a ���Choose Your Own Adventure���, but Rosie ��najdr���s take on the genre suits this rabbit hole of an issue very well: this is the children���s issue (actually vol. V, no. 8/9; Lent, 2015). It also includes the ���absurdist and imagist clusters��� of Chris McCabe���s poems for his son Pavel, with drawings by Sophie Herxheimer; Juliet Dusinberre on Arthur Ransome, setting out on a ���new tack���; and Nicholas Clark���s tour of Eric Carle���s library in Northampton, Massachusetts, where the creator of The Very Hungry Caterpillar kept, among other things, eight books about Pablo Picasso and six about Paul Klee.

May 9, 2015

In the ABBA Museum

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

“My, my, at Waterloo Napoleon did surrender . . .” Thus did ABBA burst on to the scene in 1974, victorious in the Eurovision Song Contest, held in Brighton that year. The event is upon us again soon, its image enhanced if not actually transformed by Conchita Wurst’s extraordinary performance last year.

For ABBA (Agnetha Fältskog, Anni-Frid Lyngstad, Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus) it was of course the start of a period of uninterrupted success, hit after hit until, I guess, they ran out of steam – or implausible rhymes; as people have pointed out, their lyrics can sometimes sound like the translation of a Volvo driver’s manual, but there’s no denying the catchiness of the tunes (“SOS”, “Dancing Queen”, “Mamma Mia” . . . beware those earworms!).

On a first visit to Stockholm last weekend, I couldn’t quite resist a visit to the ABBA Museum (which has only been open since 2013). This blog is not the place to write about the city’s spectacular, wonderful Museum of Modern Art, its superb Photography Museum, or the beautiful skyline, islands and waterways . . .

Among the items on display in the museum are the guitar that Björn Ulvaeus played on “Waterloo” (above), reconstructions of various recording studios, and walls of multilingual album sleeves (below) and gold and silver discs. A film clip shows the moment of Eurovision victory, the prize – handed out by a stiff, bow-tied director-general of the BBC – being accepted, bizarrely, by the songwriter Stig Anderson rather than the group itself. It being an interactive museum, you can of course perform karaoke and there’s a phone that occasionally rings – apparently, one of Agnetha, Anna-Frid, Benny and Björn will be on the other end of the line.

I didn’t know until I visited the museum that the slightly art-house Lasse Hallström, director of My Life as a Dog, What’s Eating Gilbert Grape and The Shipping News among others, cut his teeth directing ABBA videos. Extraordinary notion.

The overwhelming impression the visitor gets is that the foursome had a lot of fun while producing infuriatingly catchy pop songs in a language not their own, in the process becoming one of Sweden’s biggest exports. And they seem incredibly nice, too. The (very popular) museum, meanwhile, was an enjoyable experience. In the meantime I must overcome my aversion to Pierce Brosnan and check out the film Mamma Mia! Apparently that’s quite enjoyable too.

May 8, 2015

Andrew O���Hagan on war and writing

Andrew O'Hagan, 2011; copyright: Robert Perry/TSPL/Writer Pictures

By CATHARINE MORRIS

���I believe in the truth of what Martha Gellhorn said���, Andrew O���Hagan told Sam Leith at a ���Hidden Prologues��� event at Radisson Blu Edwardian Hotel in Bloomsbury last week. ���If you���re going to write about war, you have to taste it.��� So, in 2013, for his fifth novel The Illuminations, O���Hagan spent a number of weeks with soldiers in Afghanistan. He was not, ���even for a day���, in the kind of danger faced by many war reporters, he said, but he ���did get to taste the fear because it was straightforwardly very frightening���.

With experience as a writer, he said, ���you come to know what you���ll need for the paragraph . . . . The journalist in me absolutely races into the middle of a situation like that to get the material���. He was particularly interested in how the soldiers spoke, and in ���the rhythm of their moral lives���; he found himself troubled, when he was among them, by the impression that video games had strongly influenced their attitude to conflict. His research also took him to war graves in France, where he reflected on our ���national myth of the beauty of sacrifice���. He described the poet Charles Sorley as a talismanic voice in the writing of the book, and recited (from memory) ���When You See Millions of the Mouthless Dead���, which was found in Sorley���s knapsack after his death at the Battle of Loos in 1915:

. . . .

Give them not praise. For, deaf, how should they know

It is not curses heaped on each gashed head?

Nor tears. Their blind eyes see not your tears flow.

Nor honour. It is easy to be dead . . . .

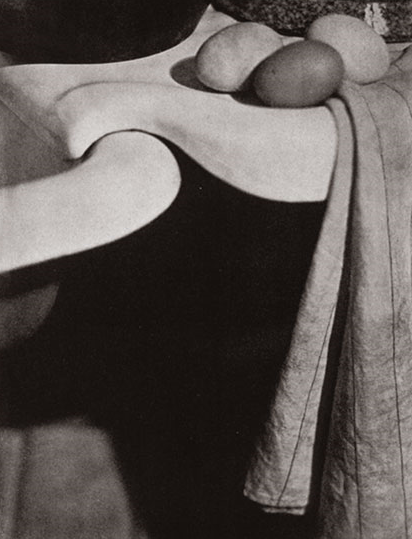

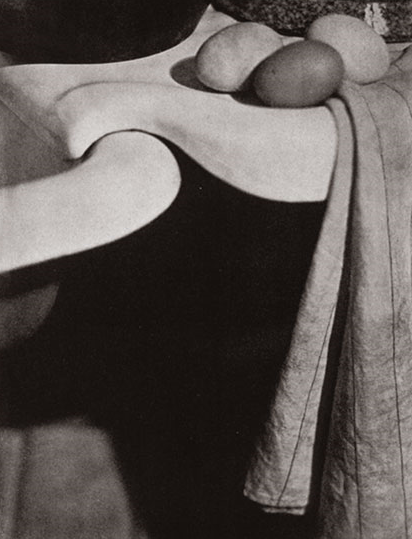

O���Hagan is interested in fiction that explores the relationship between soldiers��� lives on the battlefield and their lives at home; so, in The Illuminations (see Kate Webb���s review of the novel here), readers are introduced not only to Luke, a captain in the Royal Western Fusiliers who is leading the delivery of equipment to an electricity plant at Kajaki, but also to his grandmother, Anne, once a talented photographer, who is struggling with Alzheimer���s. Anne���s part of the story, O���Hagan told us, was inspired by the life of a Canadian photographer, Margaret Watkins (1884���1969), who, after studying at the Clarence H. White School of Photography in Maine, entered a career in commercial photography, and in the 1920s achieved international recognition for a body of work that included portraits, street scenes and domestic still lifes.

Watkins���s career was cut short when she moved to Glasgow to look after four elderly aunts. There, we were told, she became agoraphobic and stopped leaving the house ��� it is in large part thanks to a man called Joseph Mulholland, who lived near by, that she is known to us now: he noticed lights going on and off, and decided to knock on the door. Watkins later instructed him to open a particular packing case after her death; when, eventually, he did so, he found inside a huge number of negatives, contact sheets and prints dating from the period 1909���24. O���Hagan described Watkins���s photographs as ���miracles���, ���works of art���: ���she just had this absolute feeling for shape and for light��� (see ���Domestic Symphony���, 1919, and ���The Kitchen Sink���, 1919, below). Coming across her work, for him, ���was one of those moments that as a writer you get three or four times, if you���re lucky. I suddenly understood that there was a book to be written that hadn���t been written before, that was about the relationship between this woman and her vision of life ��� and her sense of the loss of her creative power���.

The weightiness of much of the conversation notwithstanding, this was a relaxed sort of evening (wine, canap��s, plush seating), and one rich in enjoyable digressions ��� on modern reading habits, for example (���I think people looked to novels once upon a time as a way to give ballast to their moral selves, and I don���t think people do that now���) and the decline of some varieties of long-form journalism (���I wrote a 12,000-word piece once about a bunch of lilies���). O���Hagan touched on writers��� certainties about what makes good and bad writing (���I'm always arguing with my friend Colm T��ib��n about this ��� everything Colm says about writing is really a justification for what he does���); and having, as a writer, strengths and weaknesses (���I was the Telegraph���s film critic for a while . . . . I don���t think I was very good at it, though . . . . Peter Bradshaw ��� he really cares whether a film���s good or not. I don���t���).

There was also an exchange with Lynn Barber, who was sitting in the audience, about approaches to interviewing: O���Hagan has had, since childhood, ���a completely insane ability to disappear���; he said of the five months he spent with Julian Assange (when working as his ghostwriter): ���He would ask for my opinion every five minutes and I���d say nothing . . . . I became like the Aga in the kitchen���. And we���ll be hard pressed to forget his descriptions of his grandmothers: one of them was ���a good-time girl. She loved dancing and singing���, while the other was ���absolutely bitter and went to Mass every day. She hated the idea that Protestants existed, and that was her main preoccupation���.

In talking about attitudes to writing, O���Hagan said: ���I don���t really believe at all in a hierarchy of forms���; ���writing well ��� it���s a bit like wanting to look all right . . . . It becomes instinctive���; and he said, of dialogue in fiction, ���If you���re serious about it, everything everybody says is filled with a kind of hinterland, and a DNA���. Meticulousness, it became clear, characterizes all his work as a writer ��� he was as thorough in his research for Anne���s part of The Illuminations as he was in that for Luke���s, spending hour upon hour with people suffering from dementia. It is not just war but all life, it seems, that needs to be tasted.

Andrew O’Hagan on war and writing

Andrew O'Hagan, 2011; copyright: Robert Perry/TSPL/Writer Pictures

By CATHARINE MORRIS

“I believe in the truth of what Martha Gellhorn said”, Andrew O’Hagan told Sam Leith at a “Hidden Prologues” event at Radisson Blu Edwardian Hotel in Bloomsbury last week. “If you’re going to write about war, you have to taste it.” So, in 2013, for his fifth novel The Illuminations, O’Hagan spent a number of weeks with soldiers in Afghanistan. He was not, “even for a day”, in the kind of danger faced by many war reporters, he said, but he “did get to taste the fear because it was straightforwardly very frightening”.

With experience as a writer, he said, “you come to know what you’ll need for the paragraph . . . . The journalist in me absolutely races into the middle of a situation like that to get the material”. He was particularly interested in how the soldiers spoke, and in “the rhythm of their moral lives”; he found himself troubled, when he was among them, by the impression that video games had strongly influenced their attitude to conflict. His research also took him to war graves in France, where he reflected on our “national myth of the beauty of sacrifice”. He described the poet Charles Sorley as a talismanic voice in the writing of the book, and recited (from memory) “When You See Millions of the Mouthless Dead”, which was found in Sorley’s knapsack after his death at the Battle of Loos in 1915:

. . . .

Give them not praise. For, deaf, how should they know

It is not curses heaped on each gashed head?

Nor tears. Their blind eyes see not your tears flow.

Nor honour. It is easy to be dead . . . .

O’Hagan is interested in fiction that explores the relationship between soldiers’ lives on the battlefield and their lives at home; so, in The Illuminations (see Kate Webb’s review of the novel here), readers are introduced not only to Luke, a captain in the Royal Western Fusiliers who is leading the delivery of equipment to an electricity plant at Kajaki, but also to his grandmother, Anne, once a talented photographer, who is struggling with Alzheimer’s. Anne’s part of the story, O’Hagan told us, was inspired by the life of a Canadian photographer, Margaret Watkins (1884–1969), who, after studying at the Clarence H. White School of Photography in Maine, entered a career in commercial photography, and in the 1920s achieved international recognition for a body of work that included portraits, street scenes and domestic still lifes.

Watkins’s career was cut short when she moved to Glasgow to look after four elderly aunts. There, we were told, she became agoraphobic and stopped leaving the house – it is in large part thanks to a man called Joseph Mulholland, who lived near by, that she is known to us now: he noticed lights going on and off, and decided to knock on the door. Watkins later instructed him to open a particular packing case after her death; when, eventually, he did so, he found inside a huge number of negatives, contact sheets and prints dating from the period 1909–24. O’Hagan described Watkins’s photographs as “miracles”, “works of art”: “she just had this absolute feeling for shape and for light” (see “Domestic Symphony”, 1919, and “The Kitchen Sink”, 1919, below). Coming across her work, for him, “was one of those moments that as a writer you get three or four times, if you’re lucky. I suddenly understood that there was a book to be written that hadn’t been written before, that was about the relationship between this woman and her vision of life – and her sense of the loss of her creative power”.

The weightiness of much of the conversation notwithstanding, this was a relaxed sort of evening (wine, canapés, plush seating), and one rich in enjoyable digressions – on modern reading habits, for example (“I think people looked to novels once upon a time as a way to give ballast to their moral selves, and I don’t think people do that now”) and the decline of certain sorts of long-form journalism (“I wrote a 12,000-word piece once about a bunch of lilies”). O’Hagan considered writers’ pronouncements on good and bad writing (“Everything Colm [Tóibín, a friend of his] says about writing is really just a justification for what he does”); and having, as a writer, certain strengths and weaknesses (“I was the Telegraph’s film critic for a while . . . . I don’t think I was very good at it, though . . . . Peter Bradshaw – he really cares whether a film’s good or not. I don’t”).

There was also an exchange with Lynn Barber, who was sitting in the audience, about approaches to interviewing: O’Hagan has had, since childhood, “a completely insane ability to disappear”; he said of the five months he spent with Julian Assange (when working as his ghostwriter): “He would ask for my opinion every five minutes and I’d say nothing . . . . I became like the Aga in the kitchen”. And we’ll be hard pressed to forget his descriptions of his grandmothers: one of them was “a good-time girl. She loved dancing and singing”, while the other was “absolutely bitter and went to Mass every day. She hated the idea that Protestants existed, and that was her main preoccupation”.

In talking about attitudes to writing, O’Hagan said: “I don’t really believe at all in a hierarchy of forms”; “writing well – it’s a bit like wanting to look all right . . . . It becomes instinctive”; and he said, of dialogue in fiction, “If you’re serious about it, everything everybody says is filled with a kind of hinterland, and a DNA”. Meticulousness, it became clear, characterizes all his work as a writer – he was as thorough in his research for Anne’s part of The Illuminations as he was in that for Luke’s, spending hour upon hour with people suffering from dementia. It is not just war but all life, it seems, that needs to be tasted.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers