Peter Stothard's Blog, page 28

March 22, 2015

From Alphabet to Zombie-like

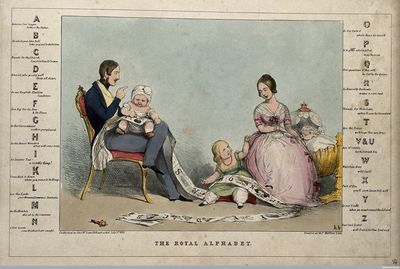

Prince Albert and Queen Victoria instructing their children; a political alphabet frames the image. Coloured lithograph by H.B. (John Doyle), 1843. (Wellcome Images)

By MICHAEL CAINES

Zombie-like? Let me explain. In case you're not familiar with it, we started running a TLS Poem of the Week several years ago, when the late Mick Imlah was poetry editor. Mick's early choices, laconically prefaced with some apposite remarks, included Philip Larkin's "Aubade" and Stevie Smith's "Pretty". More recent examples of verses first published in the paper, now selected by Andrew McCulloch for an online revival, include "Re-reading Jane" by Anne Stevenson, "Holbein" by Geoffrey Hill and John Hartley Williams's take on "Le Bateau ivre". These weekly poems have come to reflect a world of possibilities, it seems to me – of the literary imagination from A to Z. . . .

Rimbaud's poem, 100 lines and 800 words long, must be one of the grandest selections yet; by contrast, one of the shortest must be "Alphabet" by the Scottish poet Norman Cameron. As far as I know, it's the only poem by Cameron to be published – and posthumously at that – in the TLS, a "slim" piece of work that appeared in April 1964, after his literary executor discovered it among his papers. It could stand as a minimalist comment on the whole body of Cameron's work, as well as a pushing of the art of the alphabet poem to its ne plus ultra (or maybe its reductio ad absurdum):

Alphabet

After

Beauty

Cometh

Death.

Ev'ry

Flower

Gay

Hath

Its

Joyful

Kingdom

Lost –

Monarch

None

Obey.

Pleading

Queens

Reluctant

Shall

Tumble

Unto

Viewless

Ways,

eXiles

Yearning

Zombie-like . . .

Cameron's piling-up of A on B on C and so on, one word per line, strikes McCulloch as a modest sign of a "delight in the lapidary and the ludic" (see this brief account for another way of setting the poem out, as if this son of the Presbytery were George Herbert taking a break from his exercises in visual conceit). A characteristic verbal vanitas, it offers in its most concise form the same lesson in futility imparted in slightly wordier Cameron lyrics such as "The Unfinished Race", "The Disused Temple" and "Fight with a Water-Spirit". Is there a "touch of clumsiness" at the end, however, as Peter Scupham suspected – is that a further, deliberate "jest"?

Would-be poets could certainly gauge their own versatility in the same way, especially in the narrow straits of X and Z. A could stand for Always or Anyone. X might be better-off as the clinical X-ray or false-sounding Xylophone, depending on which corner the writer had by then painted themselves into. Perhaps it's a little harder than it looks. Could you make a self-representative statement out of the bare bones of the alphabet in the Cameron style?

It is not a game for everyone, I suppose. Yet the alphabet poem, or "abecedarius", has proved its tenacity over the years, and has been treated as something more than just a trivial pursuit by some. (The prize for most trivial yet recondite use of the alphabet perhaps goes to Trollope, for a joke in the opening chapter of Barchester Towers that even its modern editor describes as "heavy-handed": Trollope gives a cameo to two doctors, Sir Lamda Mewnew and Sir Omicron Pie, their names being allusions to five consecutive letters in the ancient Greek alphabet.)

It is a form of acrostic with biblical roots: God declares himself to be "Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, the first and the last" in the Book of Revelation; Psalm 119 literalizes this by devoting a verse to each Hebrew letter. Chaucer apparently pulled off the same pious trick in English, with an "ABC" that runs from "Almighty and all-merciable Queen" to "Zachary you calleth the open well". Modern variations include Alice Oswald's "Tree Ghosts" ("in which each letter commemorates a cut-down tree") in Woods Etc; An English Alphabet by the Dutchman Pierre Kemp (of which you can read the only two pages I've read here), Robert Pinsky's equally terse "ABC"; the more expansive sequence of short books by Ron Silliman, (begun in 1979 and completed in 2004 and each devoted to a separate letter); and Pinsky's "Alphabet of My Dead" (from a schoolmate called Harry Antonucci to Zagreus, "ancient god of the past").

At a less elaborate level, Cameron seems to have been playing a wry game with an established pedagogical mode when he diverted himself by making up his own "Alphabet". Numberless children will have heard one abecedarius or another over the years, whether it was by Edward Lear ("A tumbled down, and hurt his Arm, against a bit wood. / B said, 'My Boy, O! do not cry' it cannot do you good!'" and so forth) or the American lyricists Buddy Kaye and Fred Wise ("A, you're adorable / B, you're so beautiful . . ."). See also the "royal alphabet" pictured above.

In 1925, a poet who features in next week's TLS, W. H. Davies, published a Poet's Alphabet ("A is for Artist" to "Z for Zany") that at times reaches for a haunting simplicity of tone not unrelated to Cameron's:

Q for Question

The man who tell she has seen a ghost,

He either lies, was drunk or full of fears;

But if by chance a ghost should come my way,

This is my question, ready for his ears –

"What lies beyond this life I lead to-day?"

One night I dreamt I met a spirit man,

But when I told that ghost what I would know,

He laughed "Ha, ha! I knew what you would say;

And that's the question I am asking now –

'What lies beyond this life to-day!'"

The right word for such acrostic verses may be "ludicrous", as derived from the Latin for "play" but was only blessed with a sense of the ridiculous in the late eighteenth century. It seems that doesn't make ABC poems irredeemably trivial, though. On the contrary: perhaps they serve to warn poets that the attempt to sound profound in verse can sometimes keel fatally towards absurdity. Better to embrace the absurdity, maybe, as Norman Cameron did, than vainly hope it can be altogether avoided.

March 21, 2015

In praise of picture editors

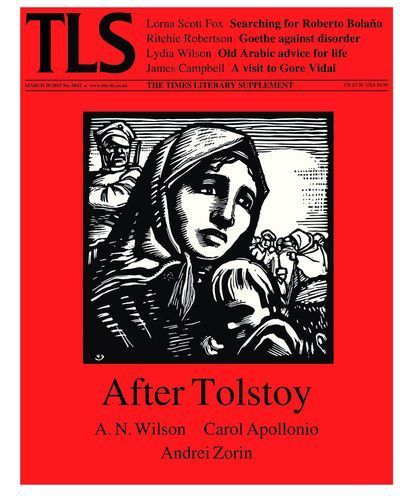

Andrei Zorin's account of War and Peace as Tolstoy's "total explanation of the current state of Russia" is now freely available on our website. This is just one horse in a Tolstoyan troika, however, passing splendidly through the village at pace: anyone who is curious, or even passionate, about Tolstoy will find more to enjoy in this week's TLS, as a glance at the issue's contents page will reveal.

That glance won't reveal the unsung feats of our pictures editor Martin Smith in bringing together, as illustrations for the same issue, a kind of miniature picture gallery inspired by the Russian master, including art by the Russian master himself: his doodles in a manuscript of Anna Karenina. . . .

There is also René-Xavier Prinet's study for "The Kreutzer Sonata", which blurrily represents pianist and violinist in a passionate (and jealously imagined?) embrace, and a striking still from Sergei Bondarchuk's film of War and Peace to complement Zorin's essay. The wood engraving on this week's cover, meanwhile, derives from the cover of an obscurity: Anissia: The life-story of a Russian peasant, an autobiographical work in which Tolstoy had a revising hand.

I suspect that that pictures editors don't get the praise they deserve. Like sub-editors and proofreaders, their existence tends to be noticed by readers only when a mistake slips through – such as our nodding acceptance once of the incorrect date for a photograph of D. H. Lawrence provided by a picture library ("Lawrence had no beard in 1908", a distressed professor observed), or the Guardian's unfortunate reproduction of a painting of the wrong John Aubrey last week, distracting from an excellent review of Ruth Scurr's new book about him – but the best of their work goes unacknowledged.

Obtaining permission to use an image from eccentric copyright holders, identifying the right mugshot amid thousands of irrelevant ones, fitting the right picture to the right space on the page: these aren't always simple matters, especially in the face of an implacable deadline. According to Martin, online picture libraries have made the job easier, whereas once "you had to rely on how a library picture researcher's interpretation of your search without really knowing the paper's picture style". The real art remains unchanged, however: "to seek out the obscure picture sources where you can find the pictures not seen a hundred times in other publications". (Have pictures editors ever been celebrated in Fleet Street fiction, by the way, beyond the vile figure of Michael Frayn's Reg Mounce in Towards the End of the Morning? I hope so, but they don't come readily to mind.)

Different publications set their picture editors different challenges, and there are obvious options for literary papers – book covers and author photos – that some use exclusively, as part of an overall design strategy, or sparingly, as contributions to a general variety. The TLS belongs in the second camp, where all the challenges of knowing how to illustrate a book review about ontology and where to find a photo of Glastonbury Tor rising above the obscured plains of Somerset (see below) reside. When I asked Martin about this, he also told me about a trend among publicists that originates in the cult of celebrity ("the bane of my life", he said, forgetting about copyright permissions for a moment). "I will put an exhibition or new film in the search box and get twelve pages of Z-list celebs attending the opening night and six images of the exhibits or stills." It is another publication, I'm guessing, that necessitates those first twelve pages.

And then there was the time he was asked to provide – not for the TLS, I hasten to add – an image of a "hippopotamus behaving strangely during a solar eclipse" . "I have to confess I had to resort to Photoshop for that one. . . ."

"The mist covers all memories, the bad as well as the good": A line from The Buried Giant, Kazuo Ishiguro's new novel, Toby Lichtig's review of which appears in this week's TLS, accompanied by the photo above (Stephen Spraggon/Alamy)

March 20, 2015

How to be a global traveller

By TOBY LICHTIG

What links Lisbon, Bodmin Moor, the Amazon, Satyajit Ray, the early Islamic caliphates and the living goddess tradition in the Nepalese Newari community? If you can answer this question then the chances are you were at the Tabernacle in Notting Hill on Tuesday night for the fascinating How To Travel and Explore evening, courtesy of the How To Academy.

What the different subjects lacked in cohesion they made up for in individual interest as six authors gave fifteen-minute lectures – rather like TED talks – on topics close to their hearts. The entry price of £25 may have been eye-watering to some, but compared to the price of the average Premier League match, the value was considerable: two intellectually stimulating halves of forty-five minutes each, broken up by a ten-minute interval. No pitch invasions, no queues to leave the venue, and no dreary post-match analysis. Apart from this blog.

First up was Philip Marsden, whose most recent book, Rising Ground, was described by the TLS's Marion Gibson as a “joyful perambulation through Cornwall, as well as through theories of space and place”. Marsden enthused about the bleakness of Bodmin Moor (“I’m not trying to sell it as a holiday destination, but rather as one of the best preserved examples in Europe of a ritual landscape”) and explained that his chief interest in neolithic stone formations was not as evidence of “functional structures” but as “works of art”. “These monuments are about reverence for the place they’re in”, Marsden commented. Many of the monuments on Bodmin Moor – ring cairns, bank cairns, view frames (in which boulders are triangulated to form a viewing aperture) – in some way point to Rough Tor, Cornwall’s second highest summit and a sacred site for the ancient architects. Marsden spoke of experiencing a similar reverence for the landscape. “I find it profoundly moving that what I feel on Bodmin Moor is in some way close to what was being felt 2–3,000 years ago.”

Ancient reverence and ritual were also at the heart of Isabella Tree’s talk – but this time in the setting of twenty-first-century Kathmandu. The “living goddess” (kumari) tradition involves the worshipping of a pre-pubescent girl selected from among the goldsmiths caste of the Newari community. The goddess (a Buddhist) is sacred to both Nepali Hindus and Buddhists. There are several of these goddesses living in Nepal at any one time and highest among them is the Royal Kumari, from whom the President of Nepal (formerly the King) must seek permission to rule by placing his head against her feet – an act of humility, said Tree, that most politicians would do well to consider.

Once these goddesses hit puberty, they are retired and replaced. Tree interviewed several of them in their later, mortal form. Most go on to live normal lives; one is now a software programmer. All spoke fondly of their former divine lives. Tree was non-judgemental, but it was hard to escape the feeling that the young goddesses are subjected to what might in a different light be considered child abuse. They are cooped up indoors all day. They must not smile, bleed or wear shoes; nor can their feet touch the outside ground. Running up and down polished floors in socks might sound like fun, but the lack of outdoor perambulation becomes a problem when post-celestial kumari have to adapt to the realities of Kathmandu’s pot-holed streets. One of Tree’s interviewees could barely walk for many months. The experience of becoming mortal again was “literally about finding her feet”.

Next, Andrew Robinson gave a diverting speech about the Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray and his embrace of eastern and western culture: a celebration of multiculturalism advanced by Justin Marozzi after half-time, this time in relation to Baghdad. Marozzi reminded us that Baghdad was once a centre of cosmopolitanism, a home to Christians, Shia, Sunni and Jews, who made up 40 per cent of the city’s population less than a century ago. He used this past tolerance as the basis for a humorous tirade against “the homoerotic death cult” of Daesh (“Don’t use the term ‘Islamic state’: it’s reprehensible”) and the group's misconceptions about the real Islamic caliphates of the Rashidun, Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties.

Unlike Daesh, the early caliphates were “progressive and intellectually inquisitive” and “enjoyed huge popular support”, said Marozzi, who went on to accuse Western media of shying away from satire about contemporary jihadism. This was a bold invocation in the light of the Charlie Hebdo killings, though Robinson’s favourite brand of humour is perhaps less pugnacious than that of the French cartoonists. Drawing on Monty Python’s Life of Brian, he finished with some words of advice to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi: “You’re not the Caliph, you’re a very naughty boy”.

After the brutal misconceptions and wanton cruelties of Daesh, it was something of a relief to flap over to the rainforests of Brazil with Katherine Rundell, a Fellow of All Souls College and a devoted rooftop trespasser, who camped out in the Amazon as research for her latest book. There Rundell learned “never to assume that an animal is dead” and found new meaning in the expression “God is in the detail”. Having witnessed the sight of floating petrol stations, submerged forests and small children driving motor boats to school (“I’d never thought it was possible to be so intimidated by a five-year-old”), she considered her most treasured memory to be of a swallow perched on a tree. It wasn’t the bird itself but the confluence of bird and place. Rundell is a children’s author and the combination of swallow and Amazon was irresistible.

As a one-time resident of Lisbon, I can confirm that some of my own most treasured memories are of swallows swooping in their flocks by the banks of the Tagus at dusk – and it was Lisbon that captured the imagination of our final speaker, Jonathan Keates. According to the publicity posters, Portugal is “Europe’s best kept secret”, though for Keates this strapline used to be reversed: under Salazar, Europe was Portugal’s best kept secret. Keates, who first visited the country under the dictator, rhapsodized about the magic of a place that appears to be mediterranean but is actually buffeted by the “vast, cruel, relentless” Atlantic Ocean. A whistlestop tour of lisboeta history – from garum (fermented fish guts favoured by the Romans), trams, fado and persecuted Jewry to the city’s great authors: “Don’t tell Julian Barnes but I think [José Maria] de Eça de Queiroz is better than Flaubert” – ended with Keates’s conclusion that “the essence of Lisbon is that it’s en route to somewhere else”.

And capturing this essence is what travel writing does best: providing us with that sense of voyage, of passing through, of dipping – however briefly and haphazardly – into another world. Looked at this way, the evening seemed even better value. Six journeys in one night for £25? Easyjet couldn’t better that.

March 19, 2015

There’s a heroine

By ROZ DINEEN

Daunt Books’s Marylebone store was looking particularly charming this morning, decked out in yellow bunting for the second Daunts Festival. The brilliant Alex Clark, Samantha Ellis and Anne Sebba took to the stage; their topic: "Choosing your heroines".

Ellis’s consideration of the female heroic began, in a way, on a walk with a friend to Top Withens (“it was properly wuthering all the way up”). Climbing, they argued about who was the better heroine – Kathy of Wuthering Heights or Jane Eyre. Ellis was all for Kathy, but at the peak she faltered, asking herself, “have I always chosen the wrong heroine?”. Here began her bibliomemoir, How to Be a Heroine.

As a biographer of women’s lives, Sebba has explored all sorts of heroics, and performed them, too. “Like a rescue mission” was how she described going after Wallis Simpson’s story. Many had Wallis down as a fantastical character, “a one-dimensional-Nazi-whore-prostitute-witch”. But she’s a “nuanced” heroine to Sebba. Other subjects, such as Jennie Churchill and Laura Ashley, “kept the marriage together, kept the home together, it’s not fashionable, but there are heroic aspects to that”.

The thing is, as Clark pointed out, we think we know what our heroines stand for, but on re-examination we often find we had it wrong. Through hearing of these writer’s processes of rereading and rescuing, we learnt this morning that new heroines can rise (and fall) out of old, familiar stories.

Who, for example, would think of Scarlett O’Hara as first and foremost an altruist, and Rhett a feminist? Yet this is exactly what Ellis found on returning to Gone with the Wind (and she added a delicious detail: that its author, Margaret Mitchell, was wrapped in a Votes for Women scarf as an infant by her suffragette mother and taken on marches).

Sebba is working now on a book about women in Paris in the Resistance and the risky things they did (a grenade in the baby’s pram, anyone?), which they later dismissed as adjuncts to the men’s activities. Inevitably the panellists accepted how many of our old heroine’s stories end where marriage begins.

Are things moving away from this model?

Yes, Ellis said: “and I think it’s always been there, we’ve just been distracted by the marriage plot”.

Here Ellis recalled the tale of Scheherazade – remember how the King married a new virgin every night, and killed her the next morning, until Scheherazade volunteered herself, “for her sisters”? She kept the king from killing her and the other women, by telling him tantalizing stories every night, for 1,001 nights (and you can read more on Visions of the Arabian Nights, in the TLS, here). Now there’s a heroine. “I hope we’re going back a bit”, Ellis said. The mainstream marriage plot may have pushed our real heroines into genre fiction, but it’s quite possible that they are pushing back.

Finally, do we still present our daughters with a feminine ideal, Clark asked – one that involves beauty, grace, elegance, rather than heroism?

“I have two daughters”, said Sebba, “and I try to tell them what matters is what you say, and do, and believe and not how you look.”

To which Clark replied: “You say it, but does everyone else say it back to them?”

This was a fantastic event that of course took in a great deal more than can be mentioned here (like Wallace Stegner, and E. M. Forster, and this, and this and Buffy).

The Daunts Festival runs until Friday night. A full programme of events can be found here.

This post was amended at 17.55pm. It was Rhett Butler not (thank goodness) Brett Butler who, frankly, etc.

March 18, 2015

Being chaste in Cheapside

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

“A play of quite exceptional freedom and audacity and certainly one of the drollest and liveliest that ever broke the bounds of propriety or shook the sides of merriment.” So wrote Algernon Charles Swinburne, as a pencil note in his copy of Thomas Middleton’s A Chaste Maid in Cheapside. Is it surprising that a city comedy, first published in quarto in 1630, could provoke such a reaction some two centuries on? And, I’d say, still do so?

Last night I saw a rip-roaring production at the Rose Playhouse in Southwark, which runs until March 28. As directed by Jenny Eastop, A Chaste Maid has a post-war setting, replicating the era of teddy boy teenagers and swinging circle skirts. A soundtrack consisting of Motown, Elvis and The Beatles guides us through the fast-paced, often bewildering, plot.

At the centre of Middleton’s play is Moll Yellowhammer, the only young virgin left – her mother and father (a wealthy goldsmith) despair – in London’s Cheapside. She’s in love with a poor man, Touchwood, but her parents betroth her to Sir Walter Whorehound, a philandering gentleman (fancifully attired here in knee-high red socks and tweed) who is having an affair with the wife of Allwit. A knowing cuckold, Allwit is tremendously pleased with this set-up so long as Sir Walter continues to pay. In a subplot, meanwhile, Touchwood's brother is so fertile that he’s forced to leave his wife – to prevent them from having any more children that they can’t afford – and sell his impregnating services, disguised as a fertility potion, to couples who find it difficult to conceive.

Moll and Touchwood. Photo: Bethany Blake

Moll and Touchwood. Photo: Bethany Blake

Depraved morals, physical grossness, mercurial obsession and ambition to climb up the greasy pole of social influence are all abundant in this view on the city, and alarmingly – even for last night’s audience – thoroughly revelled in. The Rose's revival is neatly cut to fit into ninety minutes without an interval, racing from one farcical situation to another. Timothy Harker is a perfect, compact Allwit (camp, elegantly suited-and-booted and not above gleefully singing about dildoes), in contrast to Andrew Seddon’s towering, sleazy Sir Walter. Some novel touches helped bring Middleton’s words up to date: when Sir Walter arrives at the Yellowhammers’ house, Moll mutters “Ugh death!”, then collapses in a sulk on a chair; later on, embarrassingly outwitted by the Touchwoods, Sir Walter desperately splutters after them, “losers!”.

More traditional is the minimal scenery. Two garden chairs and two arches (one with goldsmith’s weighing scales indicate the Yellowhammers’ house, the other with bull’s horns for the cuckold Allwit’s) sit either side of the stage – which is, in fact, a viewing platform for the archaeological site of the sixteenth-century Rose theatre. (This alone warrants a visit.) And if there are practical constraints on the props and scenery that can be used, it doesn’t affect the richness of the production.

I saw an excellent rendition of John Lyly’s The Woman in the Moon, here, a few months ago; again, a strong ensemble and simple staging. This time, though, A Chaste Maid uses the whole excavation – stunningly illuminated with red strip lights reflected in pools of water (see the top photograph) – for an amusing silent-film-style chase when Moll and her lover try to elope. They’re caught; there’s a sword fight; almost a death; and, finally, a marriage.

Little remorse is shown by the characters for their devious behaviour; cynicism is triumphant. Perhaps this isn’t quite what Middleton intended with his happy ending. But – the Rose being directly across the river from Cheapside and the City of London – it's irresistible to read the play now as a warning to those self-satisfied operators who still congregate there.

March 17, 2015

When Virginia found her Rachel?

Virginia Woolf by George Charles Beresford,1902; © Lebrecht Music and Arts Photo Library / Alamy

By THEA LENARDUZZI

Virginia Woolf made her TLS debut in March 1905, when she was just twenty-three, with a review of two “pilgrimage” books by F. G. Kitton – one concerning “Thackeray Country”, the other “Dickens Country”. “A writer’s country is a territory within his own brain”, Woolf wrote confidently. “No city indeed is so real than this that we make for ourselves and people to our liking”.

These comments came about five years before Woolf started work on The Voyage Out, her debut novel, published in March 1915, whose 100th birthday we mark in the latest episode of TLS Voices. (We’re joined by Hermione Lee, who needs no introduction here.)

Woolf’s novel is a pilgrimage work of a different order, the journey at its core being one of self-discovery rather than the discovery of any other. This accounts, as Lee explains, for the book’s arduous progress: though it was not published until 1915, when Woolf was thirty-three, the novelist had been struggling with it since at least 1910.

During this fraught period, Woolf continued to review regularly for the TLS, writing some 100 pieces, mainly on debut novels. She also reviewed the work of established writers, however, including The Longest Journey by E. M. Forster (“Where are the connexions? Sometime the short cut succeeds and sometimes it fails . . . . The method is clearly dangerous") and The Sentimental Traveller by Vernon Lee (“It is perhaps, the confession of a narrow spirit, but have we not heard a little too much lately about this pervasive Genius Loci?”). In Forster’s A Room with a View, meanwhile, she recognized “that odd sense of freedom which books give us when they seem to represent the world as we see it”.

Her responses to the material she was reviewing tell us something, perhaps, about where she was up to in her own writing. Indeed, it is possible that, in reviewing a biography by Francis Gribble of the great French actress Rachel Félix (TLS, April 20, 1911), Woolf found a rich source of inspiration for her own protagonist, Rachel Vinrace. Certainly the two characters have a great deal in common, from their esoteric educations to their ambivalent opinions of the opposite sex; and both women are to a degree mixtures of fact and fabrication at the mercy of writers. The actress’s father was a pedlar and, as a child, Rachel “jolted about in the back of her father’s cart, and sang at street corners”; Woolf’s Rachel, meanwhile, sets sail for South America on a vessel belonging to her father, a commercial trader.

In her review of Rachel: Her stage life and her real life, Woolf is concerned with the shortcomings of biography: there is a tendency towards over-simplification and, ironically, type-casting – “La pauvre Rachel! That is the Leit-motif . . . .We can imagine [her] reading this exclaiming, ‘Poor thing! But I’m not a bit like that’, and going up to town as gay as ever”. Mr Gribble’s broad strokes daubed over “the secret of Rachel’s sadness”: for Woolf, that lay in having to “live the life of others and not my own” – a sentiment that may as well have been uttered by Woolf’s own Rachel aboard her father’s ship. (“But what, after all”, Woolf continues, “is one’s ‘own life’?”)

Both Rachels die out of wedlock. The actress, having had many lovers, “died of exhaustion at the age of thirty-seven, having kicked her body round the world, secured no permanent happiness, and outlived her success”. Woolf's Rachel never really got the chance.

Wresting Rachel back from Mr Gribble’s too-neat characterization, Woolf ventriloquizes the actress on her death bed: “I have not been one quarter as great as I might have been. I have talent, but I might have had genius”. (Compare this with the extraordinary passage read for us by Hermione Lee, which captures the Rachel of The Voyage Out, in the grip of typhoid fever; she is a woman curled up between life and death, to whom things are done rather than who does things herself.)

“‘Ah, if only I had been brought up differently!’”, Woolf continues, speaking still as Rachel the actress. “‘If I had had different friends around me! If I had lived a better life! What an artist I should have been in that case!’” “There, surely”, Woolf (as herself again now) concludes, “is the true cry of sorrow."

And there, too, apparently, was a very fruitful commission – for Woolf and for the TLS. It may be that, in reviewing a biography of Rachel Félix, Woolf found not only a prototype for her first heroine, but also an early stirring of a current that was to ripple through much of her writing yet to come.

March 16, 2015

Ali Smith at the Wapping Project

By CATHARINE MORRIS

The Wapping Project, “an idea consistently in transition”, was founded by Jules Wright, formerly a resident director at the Royal Court Theatre and co-founder of the Women’s Playhouse Trust (WTP). It takes its name from its first home, the disused Wapping Hydraulic Power Station, London E1, where the WTP started mounting productions in 1993. The building was converted – in such a way as to retain its industrial glamour, and some of its machinery – into a versatile arts venue and restaurant.

In 2009, Wright opened a photographic gallery next to Tate Modern, which has now moved to the sumptuous Ely House in Dover Street. The Wapping Project retains its broad interest in the arts (I’m rather taken with the new residency it offers in Berlin: the successful candidate is not allowed to do any work); and on Thursday I went to the first of its “Skylight Soirées” presented in association with the New Statesman, and curated and chaired by Erica Wagner. The event featured Ali Smith; “I was thinking I might move in”, she told us as we gathered in a cream-carpeted, warmly lit room, surrounded by wood panelling and arresting photographs of Iran by Abbas Kowsari. “Nobody would notice.”

In the TLS of September 19, 2014, Kate Webb described How to Be Both as Smith’s “most thorough exploration of the art of fiction to date”. One half focuses on Francesco del Cossa, a real-life artist born in the 1430s who painted some of the frescoes in the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara; and the other on George, a teenage girl living in modern-day Cambridge who is coming to terms with the sudden death of her mother. (As Webb explained, there are two versions of the novel – in one, George’s half comes first, and in the other, it is Francesco’s; when you pick up a copy in a bookshop, you don’t know which you’re going to get.)

Smith read out a passage in which George is watching porn videos on her iPad out of curiosity, and feeling a profound sympathy for one actress in particular (“the uncomplaining smallness of the girl alongside her evident discomfort and the way she looked both there and absent . . . changed something in the structures of George’s brain and heart”). She then read another in which Francesco visits a brothel, where he (or in fact she: in the world Smith has created, Francesco is a woman who cross-dresses in order to live as an artist) politely refuses the services on offer and draws one of the prostitutes instead.

It was Tom Stoppard, Smith told us afterwards, who gave her the courage to write about the Renaissance period (she is not a specialist); she happened to be sitting next to him at a dinner, and he offered the metaphor of a letter sitting in front of you on the table: “only lift the corner of the envelope and peek in”. There is very little written about del Cossa; the only reason we know he existed at all is that he once wrote a letter to his employer (a duke), asserting his worth and asking for more money. At the beginning of Francesco’s half of How to Be Both, he is very physically ripped from his own time and brought into George’s: “Ho this is a mighty twisting thing fast as a / fish being pulled by its mouth on a hook . . . ” (that forward slash is necessary, I think: the text of the passage is itself set like a twisting thing, as you can see here). When a member of the audience confessed that she had found that passage difficult, Smith replied that it provided above all “a voice from elsewhere”. And it is a voice with some basis in reality: Smith studied del Cossa’s letter to the duke and used its rhythms and idiosyncrasies (one of them being its punctuation – he used a lot of colons) to build a whole person.

Smith described del Cossa’s frescoes as “so mysterious and yet familiar to us . . . . Something about them radiates meaning but we don’t know what the meaning is any more”. This was during a multi-faceted discussion about art and death that took in Hannah Arendt, whose introduction to Illuminations by Walter Benjamin provides one of How to Be Both’s epigraphs (“Although the living is subject to the ruin of time, the process of decay is at the same time a process of crystallization . . . ”) and Benjamin himself. It was a discussion facilitated by some wonderfully high-end questions and comments from the audience: one took us briskly from Wordsworth’s “spots of time” to Blake’s “Echoing Green”, and on to Lacan.

Minutes before the end of the evening, Smith was asked, in relation to her interest in narrative and its possibilities, whether there was somebody in particular who had inspired her. The answer she gave was not only amusing but also quietly revelatory:

“Probably my mother . . . I’m about five or six . . . and she would bath me and then sit me on her knee and then she would simply become another character . . . . she was just a master of imagination . . . . The characters ranged from two old witches called Gertie and Bella . . . [to] this hard put-upon character from the Hebridean islands called Morag . . . : ‘I’ve got the hens to feed . . . Oh dearie me’ . . . . And I . . . knew immediately at that point that it wasn’t about story in the same way as it was about voice, or the shift of voice, the movement of voice . . . the way in which we are all filled with the multitude of voices that exist or can exist – the ways in which a story will simply fall out of a voice . . . . I think it was something like that.”

March 12, 2015

Notes from the archive: T. S. Eliot and the Second World War

By BENJAMIN POORE

In a musty basement in Mayfair, boxed up beneath the offices of the English-Speaking Union (above), are the yellowed and mildewed papers that archive one of T. S Eliot’s contributions to war work.

It is fifty years since the poet’s death, but not many people know that at the end of his life he was the chairman of a large educational project called Books Across the Sea (BAS), set up in 1941 by the American typographer and anti-Fascist activist Beatrice Warde to counter Nazi propaganda that attempted to sunder relations between Britain and America (Lord Haw-Haw being a well-known example). Eliot was made president of the organization in 1943. It might be one of the most material expressions of his trans-Atlanticism – this aspect of his life and work is elaborated in Robert Crawford’s new account of Eliot’s early years.

For Warde, “mental mobilization” was vital. Everyone agreed that knitting and rolling bandages were important, she wrote, but “how often do you come across a work party of literates who are determined to wrestle with certain dangerous misconceptions that are causing trouble . . . between one Allied people and another?”

Books were the answer, and they were scarce: in 1942 Warde wrote that England was experiencing “a book famine”. “At least 20,000,000 books have been destroyed in the burning of libraries and publishing houses. The works of George Bernard Shaw…are now out of print. Yet the people are turning to reading as they never did before for escape from war strains.” The destruction of books was at the moral heart of the war effort: “The country [Germany] that began by burning its own books reached a climax in its war on enlightenment.” The fragments shored against the ruin of European civilization at the end of The Waste Land are themselves in danger of turning to cinders.

The plan was that books, especially those out of print, should be exchanged between the United States and Great Britain, as regularly as possible, and on broad topics: literature and poetry, of course, but also books on farming, ideas about postwar reconstruction, political and social history, environment and landscape. These were “Ambassador Books”, for informal discussion groups hosted by schoolteachers and open to everyone, especially the young.

They would themselves respond in making a “Hand-Made Book”, a “regional daily life scrap book”, which would travel back to the US. “Easily ten thousand young people”, a BAS document reported in 1945, “have played some direct or indirect part in the making of a book…Few of these young people will ever again imagine that ‘book’ means ‘dull mysterious thing churned out in quantity by Experts for High-brows’.”

Among Eliot’s papers I found old clippings from the TLS. In a piece from November 11, 1944, Eliot stressed the complementary character of the project’s activities. “For every piece of work done here”, he writes, “a parallel piece of work has been done by the New York circle.” “The provision of books and information about America is only one half of the book: the other half consists in supplying New York with books and information about Britain.”

Elsewhere, Eliot insisted that “the way to maintain democratic friendship between people is to multiply direct contacts between individual and individual and between group and group”. During the war, Lyndall Gordon, from the University of Oxford, suggests, Eliot came into contact with different sorts of individuals, “not the intellectual elite who had always welcomed him . . . but groups of ordinary people”; Eliot was trying “to feel his way into that sense of community”. Peter Ackroyd’s biography notes that wartime saw an impulse in Eliot that strove for “a common style”. The appeal of BAS is, in this respect, obvious, and might resonate in some ways with Eliot’s more reactionary cultural politics.

The end of the war did not see the end of the project (it continues to this day, organized by the English-Speaking Union, with whom it merged in 1946). A faded newsletter from 1946 notes that Eliot, in his Presidential Address, made a “statement of faith in the permanent establishment of Books Across the Sea”. Eliot was uneasy about the recently established peace, and saw a creeping instrumentalism compromising the “spiritual organisation” of modern life; after the war, Ackroyd writes, Eliot felt the “world was a less ‘moral’ place than it had been before”.

Eliot’s poetry can seem thousands of miles from the sentiment of this wartime project and its ad-hoc, amateur, exploratory approach. We tend to forget that there are children’s voices in The Four Quartets. But it is the juvenile energy and capriciousness of children making their own scrap books that stands out in Books Across the Sea. It also suggests a different Eliot: less T. S., perhaps, more Tom.

March 11, 2015

Double Deutsch

The novelist Isabel Colegate is best known for The Shooting Party, published in 1980, in part because of the film adaptation that quickly followed. Her first novel, The Blackmailer, has a more interesting claim to fame, a story from the small world of mid-century publishing that I believe she's written about before, but which I only discovered from the reissue published last year with a new foreword. . . .

Yes, as the title tells you, The Blackmailer involves blackmail: the brisk plot centres on a war hero's widow and the man who threatens to expose her late husband's true nature. Quite apart from the pleasures of the witty novel itself, though, are the author's opening remarks about the qualms of the publisher to whom it was first submitted, Jonathan Cape.

There, Colegate notes, the chief editor Robert Knittel became convinced that she had based one of her supporting characters, a publisher called Feliks Hanescu, on the well-known André Deutsch – "whom I never met". Cape declined to publish The Blackmailer and it appeared in 1958, under a new imprint set up by Anthony Blond, with whom Colegate had formerly worked as a literary agent. The TLS (for which Colegate would later write superbly) reviewed the novel positively, but did mention that it featured "some highly unlikely characters".

To Knittel, it seemed impossible that Colegate could have made up Feliks, however unlikely he appeared to be – this ambitious chap of Eastern European origin who wanted to be a "genius" but, failing that, settles for becoming a "personality", who "enjoyed scenes but preferred them to be engineered by, and centred upon, himself". Hanescu is of "Rumanian" origin and Jewish; Deutsch was of Hungarian origin and Jewish. Deutsch founded his own firm, Allan Wingate, in 1945, from which he was ousted a few years later; Hanescu sets up in 1945, only to be declared bankrupt eighteen months later. Both then establish their own firms.

To Deutsch's former partner Diana Athill, he was a "born publisher" – he once wrote an anonymous, worldly piece in the TLS about the perils that beset a young publisher:

"To the young man who has a few thousand pounds to play with and wants to become a publisher, it all seems so easy. Almost everybody, it appears to him, is writing a first novel or has a collection of short stories . . . Thus another new imprint is created, and as soon as it is heard of the unfortunate young man will be flooded with third-rate manuscripts from writers and agents. . . ."

Deutsch's supposed counterpart, meanwhile, gets back into business when his father dies, leaving him with, naturally, "a modest fortune":

"Feliks Hanescu had energy, talent, salesmanship, and an infinite capacity for remembering names. He also had, for the moment, a considerable unearned income. He soon acquired . . . a large clientele of ex-convicts, war heroes and deep-sea divers, who, greedily pursued by other publishers, came to him . . . partly because they had heard he was good at pushing sales, which was true."

All this was apparently enough to put Knittel in mind of Deutsch. Colegate told him, as she recalled in an earlier reissue of the book, that it wasn't anything so simple: "I don't think he believed me". The new foreword's implication is that a recognizable portrait of such a person was one reason, if not the only reason, for the book's rejection – and if so, this is a far cry from the current mania for fictions that are acknowledged variations on the themes of the authors' own lives, as in the tedious Outline by Rachel Cusk or the ongoing Neapolitan saga of the (pseudonymous) Elena Ferrante.

(Yet the 1950s was also the decade in which Anthony Powell began his Dance to the Music of Time, at least three volumes of which appeared before Colegate's book fell into Knittel's hands. So maybe I've misunderstood the significance of that accidental portrait of a publisher in The Blackmailer, which does indeed seem a reasonable enough likeness, but hardly a lampoon.)

It is tempting (because we are incurably nosey about this sort of thing?) to pin Powell's characters to their "counterparts" in real life – to match up X. Trapnel and his trappings with those of Julian Maclaren-Ross, for example, or Mona Templer's profile to that of Sonia Orwell, and so on. But this is to ignore Powell's own exasperation with critics who could not grasp the principle of composite characterization – that fictional characters in novels may be, as Colegate now puts it, "composites of people one has known or met, people one has read about or glimpsed on the bus, and oneself".

So even if Colegate never met Deutsch, Blond had worked for Allan Wingate, his old firm, and, while she remembers being "incapacitated by shyness", it was Blond who would "venture out into the cut and thrust of the literary world, returning with tales which I suppose provided the material for the character of Feliks": "Feliks of course is a creature of fantasy but characters not immeasurably different could adorn the publishing trade in those days".

Perhaps this capacity for "invention as well as manipulation" lies at the heart of the matter: if you find it "hard to believe" that a character in a work of fiction could be just that, you might as well believe that Shakespeare couldn't possibly have been a relatively ordinary person with an extraordinary mind. And yet an impish muddling of the two seems to be exactly what imaginative literature requires of its creators. Colegate remembers how the "French troubles in Indo-China" made the news at some point, and there were possibly rumours about a siege and a "gallant officer" – perhaps it was then that the "soup of the stuff of dreams began to bubble. It bubbles less easily now that I am old, which is why I look back on The Blackmailer with a certain affection".

André Deutsch, 1962 © National Portrait Gallery, London

March 9, 2015

Influences of the 1980s and beyond

By MICHAEL CAINES

And finally – that is, finally as far as this dusted-down list of influential books is concerned (see this blog about a month ago for the 1940s and onwards) – we come to that lowest-of-the-low, that most dishonest of all post-war decades (discuss): the 1980s. . . .

A couple of these books belong to the 1990s, in terms of chronology of publication – so these are perhaps the most adventurous choices made by those experts in the "common market of the mind", the Trustees of the Central and East European Publishing Project (CEEPP), who produced this list as a parting jeu d’esprit before they disbanded. I wonder how that decade could be completed if a similar group compiled such a list today, and what the 2000s would look like. And as for beyond – I'm immediately stuck at one obvious example, Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century. A researcher in intellectual influence in the Department of Influence Studies could do worse than attach the equivalent of a GPS tracking device to Piketty's book and follow it everywhere.

Despite the title, this Capital is, as Duncan Kelly puts it in his TLS review, "as much a story about the limits of modern democratic politics as it is about the structures of inequality", as much a story with large historical implications as a diagnosis of present discontents and possible future solutions, that could have an "electrifying" effect once its insights are "eventually fused into new histories of economic and political thinking about global competition". Its implications may interest those who, Kelly suggests, are simply interested in clearing up the "real confusion about how our current system of capitalism in the twenty-first century actually works".

See below for some further recommended reading – and a few pertinent excerpts from the TLS reviews of the time or later. As I've read only a few of these myself (Milan Kundera and Primo Levi, yes; ah, The New Palgrave . . . no), these are useful reminders for me at least that influence can touch one's own reading indirectly, just as Piketty's politico-economic predecessors acknowledged by the CEEPP may exert, through him, an intangible influence on today's many readers of Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

*

BOOKS OF THE 1980s and beyond

86. Raymond Aron: Memoirs (Memoires)

". . . it is clear that Aron was haunted by the celebrated phrase, 'better to be wrong with Sartre than right with Aron'. He points out, legitimately, that the idea that they were opposites is in fact stupid and first arose out of a misconceived television interview." (Douglas Johnson, 1983)

87. Peter Berger: The Capitalist Revolution: Fifty propositions about prosperity, equality and liberty

"Whereas many sociologists bury their messages in impersonal passives and a conglomerate German-American, this emigrant writes in humane literary English with a strong tincture of lived experience and humour." (David Martin, 1997, reviewing Berger's Redeeming Laughter)

88. Norberto Bobbio: The Future of Democracy (Il futuro della democrazia)

". . . the leading Italian political theorist of the post-war period . . . Bobbio’s work was as academically innovative as it was politically significant." (Richard Bellamy, 2004)

89. Karl Dietrich Bracher: The Totalitarian Experience (Die totalitaere Erfahrung)

"The experiences of the twentieth century have been so varied, its ideologies so shifting and contradictory, its prophets – Max Weber or Oswald Spengler or George Orwell, for that matter – so often both right and wrong that it is hard to write a work of synthesis which really holds together. This Professor Bracher has undoubtedly done." (James Joll, 1983, reviewing Bracher's Zeit der Ideologien)

90. John Eatwell, Murray Milgate and Peter Newman (eds): The New Palgrave: The world of economics

"At a casual but conservative guess, the world's professional economists are adding to the discipline's written record at least a yard of shelf-length every day. . . . A reference work of this kind needs every defence against creeping inundation by the economic matter that is published every day." (Paul Seabright, 1988)

91. Ernest Gellner: Nations and Nationalism

"Gellner does . . . provide a better explanation than anyone else has yet offered of why nationalism is such a prominent principle of political legitimacy today. . . . But although it is the product of great intellectual energy and an impressive range of knowledge, it is not a complete success." (John Dunn, 1983)

92. Václav Havel: Living in Truth

"When Václav Havel's essays began to appear, they signalled a renaissance in political theory. Today, they provide essential reading as witness, prophecy, contributory cause as unrivalled explanations of the revolutions of 1989, which have so extraordinarily propelled him from a prisoner of conscience [to] Europe's only philosopher-king." (Jeremy Adler, 1990)

93. Stephen Hawking: A Brief History of Time

"He is a physicist whose high genius is readily acknowledged by his peers. Members of the public at large can only take this on trust, but . . . they have made his A Brief History of Time into a record-breaking best-seller. How well it has been understood is hard to say." (John D. North, 1992, reviewing Stephen Hawking: A life in science by Michael White and John Gribbin)

94. Paul Kennedy: The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers

"[It] has had a remarkable impact in the United States since its publication late last year. It has been widely and almost universally favourably reviewed. . . . What has made this book the phenomenon it has become is that it speaks to one of America's deepest, most troubling anxieties: the fear of national decline." (Alan Brinkley, 1988)

95. Milan Kundera: The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

"Given the existence of limits, of the border, the individual has to choose to respect it or go beyond it. . . . [Kundera] is convinced that the individual is too vulnerable to hold out alone against totalitarian institutions. If one takes flight then one deprives those left behind of the support necessary for survival." Alan Bold, 1982)

96. Primo Levi: The Drowned and the Saved (I sommersi e i salvati)

"One is somewhat startled to find that Levi is able to leaven so grim a topic with an urbanely ironic wit – particularly evident when Levi is observing some of the less immediately homicidal Nazi lunacies. But sadly, for all the refined control of his writing, it would seem that Levi died in despair, still haunted by the nightmare that only the Lager is real." (Hugh Denman, 1987)

97. Roger Penrose: The Emperor’s New Mind: Concerning computers, minds, and the laws of physics

"When experts talk to experts, they are careful to err on the side of under-explaining the fundamentals. One risks insulting a fellow-expert if one spells out very basic facts. . . . So perhaps educated laypeople are only the presumptive audience for this book, hostages to whom he can seem to be addressing his remarks, so that the experts – his real target audience – can listen in, from the side, without risk of embarrassment." (Daniel C. Dennett, 1989)

98. Richard Rorty: Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature

"Perhaps the crowning achievement of this immensely rich and interesting book . . . is to constitute a pragmatic self-refutation of the author's main thesis." (Charles Taylor, 1980)

99. Amartya Sen: Resources, Values and Development

"Sen is here hacking his way through a conceptual and moral undergrowth that most market economists leave severely alone." (Michael Lipton, 1985)

100. Michael Walzer: Spheres of Justice

"If he is right in his main arguments, each of these problems deserves a book – nay, a philosophical controversy – of its own." (Jeremy Waldron, 1983)

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers