Peter Stothard's Blog, page 26

May 7, 2015

Up Jumped Nick Cave

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

Nick Cave is an oddball. His music, writing, performance – everything about him, or what we can make out about him, is a strange, intense mixture of menace, chaos, gentleness and self-mockery. We like him when he calls us “motherfuckers” and tells us to “fuck off”, as he did several times at the Royal Albert Hall on Sunday night. We cheered louder when he coolly threw his mic over one shoulder to resume playing the piano during a mesmerizing delivery of “Higgs Boson Blues” (poor – or lucky? – person in the front row who was caught by the flying mic stand). At one point, he invited a few members of the audience onto the stage, group-hugged them, and then abandoned them to continue parading up and down the aisles of the stalls, looming over us like a bird of prey, pointing in faces and touching heads as if granting absolution: “Can you feel my heartbeat? / I’m talking to you / My heart goes boom boom boom boom”.

In 20,000 Days on Earth (2014), a docu-fiction film in which Cave plays himself, he says that rock stars must be “god-like”. And indeed he was on Sunday evening: from his haunting piano-solo ballads, such as “Water’s Edge”, which was introduced by Warren Ellis's (of the Bad Seeds) mournful violin, to Cave’s powerful whispers at the beginning of “From Her to Eternity” that impressively erupted into anarchic clashing chords and Thomas Wydler’s manic outbursts on the drums. On the first gleeful ding of the bell in the song “Red Right Hand” – the phrase is taken from Milton’s Paradise Lost – the entire auditorium was saturated in red light.

Reminders of early Cave came from a performance of “Up Jumped the Devil”. Here he brashly hammered on a comically tiny xylophone during the chorus (the sticks were also tossed over one shoulder). “This song was about being drawn into hell”, he told us before he began, “but I don’t believe in that anymore.” Maybe not, but his lyrics since then haven’t lost their (often playful) references to doom, death, the devil or the soul. Just a handful of examples from his set: in “Mermaids”, he sang, “I believe in God / I believe in mermaids too / I believe in 72 virgins on a chain”; in “Jubilee Street”, “I’ve got a foetus on a leash”; and in “Higgs Boson Blues”, one of his most fanciful tales, “If I die tonight, bury me / In my favourite yellow patent leather shoes / With a mummified cat and a cone-like hat”.

For the encore, as well as the beautifully elegiac “Push the Sky Away”, he sang a cover of Leonard Cohen’s “Avalanche”. “I saw him play here”, Cave said. “It was quite good.” There was a lot of endearing dialogue like this, especially between Cave and Ellis: “I can’t see you over there”, Cave called to Ellis halfway through the show, “it’s your beard”. (The lighting technician spotlighted Ellis from then on.)

“There’s something that happens on stage”, Cave tells us in 20,000 Days on Earth. “You’re transported and time has a different feel and you are just this thing and you can’t do any wrong. Then you look down the front row and somebody yawns. And the whole thing falls away and there’s just this schmuck . . . .”

Cave simmered and surged for nearly two and a half hours without a break on Sunday night. No one was yawning.

May 5, 2015

Women and the Mexican golden age

By THEA LENARDUZZI

One of the most striking things about the 1948 Mexican film Salón México – screened last night as part of the Barbican’s "Women and the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema" season – is how contemporary it feels. Leave to one side the dizzying melodrama of Emilio Fernández’s camera work, mute the more orchestral elements of the soundtrack, and you’re left with the simple tale of a strong woman – Mercedes, played by Marga Lopez – let down by a society in which sexism is the norm and change is not forthcoming.

This cabaretera – an exhilarating mix of melodrama, cabaret and noir; like mid-period Hitchcock with added spit 'n' sawdust and a rumba beat – is set in Ciudad Juárez where Mercedes works as a dance-partner, sold by the boss of the Salón México to the highest bidder. Her only drive is to earn the money to put her younger sister, the blessed Beatriz, through boarding school: “I want to see her become a doctor and get married”; elsewhere, she hopes that Beatriz will grow tall, to be up there “where there are no shadows, no horrors”. But Paco, a mobster with extraordinarily high-waisted trousers (one of very few comical things about him) swindles Mercedes out of her share of their winnings – “We won the contest together!”; “Don’t be impertinent” – and in the end, in true cabaretera style, her future. It seems all too logical a continuation that Juárez should now be known (as Lucy Popescu points out in her review of La Lucha: The story of Lucha Castro and human rights in Mexico, in this week’s In Brief pages), as the "femicide" capital of the world.

Fernández, working with the cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa (five years earlier the pair had collaborated on María Candelaria, also showing at the Barbican; it was the first Mexican film to be screened at Cannes and the first Latin American film to win the Grand Prix), brings to life a country of deep contrasts and ironies, positioning them carefully around the central metaphor of dance. The most stark of these is that a country so proud of its independence can keep half of its population enslaved.

The scenes of the two sisters celebrating the anniversary of Mexican independence around the Zócalo, Mexico City’s main, officially known as the Plaza de la Constitución, are worth watching for the early footage of the square alone – see 1:47 here:

Since shortly after the May rallies of 1968, when students gathered to protest the increasingly authoritarian policies of Gustavo Díaz Ordaz (the Tlatelolco massacre, in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas, came just a few months later), the square was left to ruin; eventually it was paved over entirely, and that is how it remains today. (The word Zócalo, meaning plinth, is the only trace of plans to erect a monument to independence; only the plinth was built – long since destroyed – which says it all, really.)

As Lupe Lopez – a kindly policeman who becomes something of a guardian angel to Mercedes – puts it in Salón México: “Everyday I move further from understanding things . . . . I don’t know where we’re headed”. His name – a reference to the Virgin Guadalupe, one of the country’s patron saints – is just another twist of the knife: “I am the last representative of the law”, he tells Mercedes sadly. And that really isn’t enough. As the film draws to a close the band strikes up a slowed-down version of the classic “Juárez no debió de morir”: “If Juárez hadn’t died, things would have been different . . . . If Juárez hadn’t died…”

May 1, 2015

Wonderland at war

By MICHAEL CAINES

In 1948, two Polish emigrés in London, Stefan and Franciszka Themerson, set up the Gaberbocchus Press, the name being a Latin spin on Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky”. Working initially with a hand press, they would go on, over the next three decades, to publish an average of just a couple of new books every year – and what books they were.

Among other notable firsts, Gaberbocchus published the first English translations of Ubu Roi; Raymond Queneau’s Exercises in Style; The Good Citizen’s Alphabet by Bertrand Russell; and other works by Stevie Smith, Kurt Schwitters and the Polish futurist poet Anatol Stern. These publications, “best lookers” rather than “best sellers”, are also examples of a sound principle (for small publishers? for all publishers!) put into practice: that “the design of each book should be an expression of its content”.

The Themersons were artists in their own right, who collaborated on experimental films and children’s books. The TLS welcomed the “wit and the precision and the merciful economy” of Franciszka’s drawings for Ubu Roi, and later the “many rum non sequiturs” of Stefan’s novel Mystery of the Sardine. It is only from the recently published Unposted Letters, however, that I have learned what led up to this settled post-war life: a period of intense uncertainty, with Stefan stuck in France, and Franciszka stuck in England. One of them was reading Alice's Adventures in Wonderland . . .

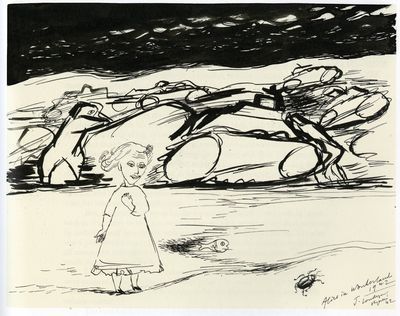

Alice – the object of numerous 150th anniversary celebrations this year – was Franciszka’s inspiration for the drawing above, of a frowning girl with a fixed smile, wandering through "Wonderland". In the foreground are a beetle (escaped from the Looking-Glass train carriage?) and a fish; behind her, the tanks roll by.

The Themersons had moved to Paris a year before the outbreak of the Second World War; they were decisively separated in 1940 when the Polish government-in-exile retreated to London, taking Franciszka with it, and the Polish Army chaotically disintegrated, leaving Stefan stranded in France. The “unposted letters” of the next few years were not only verbal but visual, as Franciszka drew and wrote her way around her anxieties. “I work all day and talk with people and smile while my heart shrivels up with worry . . . hopelessly sad . . . Our nearest and dearest live in such torment. It’s unbelievable.”

“Today, the whole evening I am drawing – actually these are also letters (or a diary?) to you. . . . I have to do something that reminds me that I am human." "Help! This is the only word that I should really write”, she admitted in 1941, and Jasia Reichardt, the editor of Unposted Letters, adds a note directing the reader to the relevant drawing, emblazoned with that single word, of Alice-Franciszka beneath what seem to be a pair of bomber planes with broad grins.

On many occasions, the couple did manage to exchange letters and telegrams. Receiving one from Stefan, Franciszka says: “I sat down beside it and sat for five minutes before I opened it. Our black cat here, who thought that he knew my habits, sat opposite me and his ears stood up in amazement”. She tells Stefan how she has been amusing herself by writing “funny autobiographical ferdydurki” – meaning funny autobiographical nonsense, alluding to the title of Witold Gombrowicz’s great first novel rather than Carroll this time.

Stefan ruminates on literature: “Pickwick Papers is also now a book for children. And so are the figures of Don Quixote and some pages from Rabelais, but Alice in Wonderland may one day be a book for adults. I think that Shaw and Chesterton, whole volumes of Anatole France and Diderot’s Jacques le Fataliste will be for children one day”. He reads Ulysses in French: “900 solid pages of small print. What absorbing reading. The approach of a scientist in a wonderland . . .”.

Unposted Letters is full of the traces of vital practical matters, such as Stefan’s attempts to gain a visa, but I’m struck by this particular aspect of it – by its demonstration that the avant-garde, free-ranging Themersons of the 1930s (when they made most of their films) didn’t altogether retreat into artistic hibernation during the war years. Instead, as those allusions to Alice perhaps suggest, they seem to have been groping their way towards Gaberbocchus.

As when Franciszka asks Stefan this question (but doesn’t post it): “in Paris you were clearly in the ascendant, with growing power and greater impetus. – Have you found a way to hold on to all that?” And she draws him sitting at his desk:

As much as the war is affecting them – keeping them apart, perhaps permanently – she suggests how an artistic life is a life apart from these minor matters:

“I’m conscious all the time that small talk is not our world. That the only real sense of communicating with people is greeting through the written word or by some visual form . . . What sincere and real friendship I feel for Carroll or Czukowski, how close to me is this or that painter or composer, even if they’re unknown to me by name.”

Stefan, for his part, happily observes that the sprig from a cherry tree he put in a water glass on his thirtieth birthday has budded overnight: “I shall put a red pencil behind the glass and will have a picture by van Gogh when they bloom”. Who needs nature when you can have a Van Gogh?

Their reunion in the summer of 1942, in England, was soon interrupted when Stefan was sent off to Scotland, to rejoin the Polish forces; Reichardt notes that their mothers both committed suicide a few days later, in the Otwock ghetto, not far south of Warsaw, as its liquidation began. Of their pre-war life, perhaps the most poignantly innocent remnant is this short film, The Adventure of a Good Citizen. It is the only one of five pre-war films of theirs to have survived the war. Franciszka’s Paris paintings are apparently all gone, too. Troubles of another sort meant that it wasn't until after her death in 1988 that her fifty-seven illustrations to the second Alice book appeared in print as intended. There is a Mad Hatter, meanwhile, in Stefan's Mystery of the Sardine, published in 1986 (he, too, died two years later).

After the great separation of those dark years, the ferdydurki would never be the same again.

April 30, 2015

The TLS at Brighton

By TOBY LICHTIG

The Brighton Festival kicks off this weekend with an exciting programme of literature, art, music, theatre, film, dance and debate over three (count ‘em) culture-filled weeks.

The festival is guest directed by the recent winner of the Costa Novel award and Goldsmiths Prize (not to mention TLS contributor) Ali Smith, and includes two TLS-sponsored events.

Next Wednesday (May 6), at 8pm at the Dome Studio Theatre, the former Times literary editor Erica Wagner will be talking to Ruth Scurr, whose study of John Aubrey was described by Stuart Kelly in this paper as a “formidable and astonishing achievement” – and one that manages to extend the very boundaries of its genre: “a biography of a biography that doubles as an experimental analysis of biography”. Scurr has resurrected Aubrey – a biographer, of Christopher Wren, Isaac Newton and Thomas Hobbes among others – as a potent spirit for our own time.

On Sunday week (May 10), at 5pm at the same venue, the TLS contributor Caroline Moorehead will appear alongside the historian Roderick Kedward in conversation about the history and legacy of the French Resistance. Moorehead’s recent book Village of Secrets: Defying the Nazis in Vichy France tells the extraordinary story of a French village that helped to save thousands of citizens who were pursued by the Gestapo during the Second World War. Reviewing Moorehead’s book in the TLS last year, Matthew Cobb found the events described “incredibly moving because they involved ordinary people doing extraordinary things in the most extraordinary circumstances”.

Kedward is the author of, among many other things, the groundbreaking study Resistance in Vichy France, based on a series of interviews conducted in the 1960s with ordinary men and women from the Resistance. These testimonies have now been deposited at the Keep in Brighton and are the starting point for a new Centre for Global Resistance Studies at Sussex University. The discussion will be chaired by Martin Evans, Professor of Modern History at Sussex University and the author of Algeria: France’s undeclared war.

April 29, 2015

PEN pals

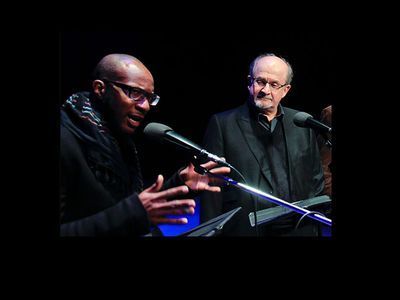

Teju Cole and Salman Rushdie discuss their work at Symphony Space’s Selected Shorts, hosted by the Time Out New York, December 2014. Photograph: Rahav Segev/Symphony Space

By MICHAEL CAINES

In a few days’ time, PEN American Center will hold its annual gala dinner in New York, and will give the PEN/Toni and James C. Goodale Freedom of Expression Courage Award to Charlie Hebdo, the Parisian “journal irresponsible” – for the obvious, awful reason.

The past few days have ensured, however, that diners’ attention will be divided between the presence of two of the magazine’s surviving representatives – Gérard Biard and Jean-Baptiste Thoret, who are due to collect the award – and six notable absentees. . . .

As reported in the New York Times this weekend, the writers Peter Carey, Teju Cole, Rachel Kushner, Michael Ondaatje, Francine Prose and Taiye Selasi have withdrawn as “table hosts” for the event, rousing the ire of those who like to howl about free speech in the usual forums. Adam Boulton, a television presenter, rose to the occasion to put out this, the ultimate barb against Carey:

What Salman Rushdie had originally said was this: “The award will be given. PEN is holding firm. Just 6 pussies. Six Authors in Search of a bit of Character”.

More helpfully, the writers themselves and PEN's official representatives have stated their views. See the response from the director of English PEN, Jo Glanville, the statements by Kushner and Carey in the NYT, George Monbiot’s dialogue-in-tweets with Rushdie (“2 sound values – pro-free speech, anti-hate speech – can conflict”). And Cole – who is described on his website, by the author of The Satanic Verses, as one of the “most gifted writers of his generation” – has told The Intercept:

“I’m a free-speech fundamentalist, but I don’t think it’s a good use of our headspace or moral commitments to lionize Charlie Hebdo in particular. L’affaire Rushdie (for example) was a very different matter, as different as blasphemy is from racism. I support Rushdie 100%, but I don’t want to sit in a room and cheer Charlie Hebdo. This distinction seems to have been difficult for people to understand, and any dissent from the consensus about Charlie Hebdo is read as somehow 'supporting the terrorists,' or somehow believing that they deserved to be murdered.

"I would rather honor Raif Badawi, Avijit Roy, Edward Snowden, or Chelsea Manning, who have also paid steeply for their courage, but whose ideals are much more progressive than Charlie’s. I would like an acknowledgement of the Kenyan students who were murdered for no greater crime than being college students. And, if we are talking about free speech, I would rather PEN shed more light on the awful effects of governmental spying in the US, and the general issue of surveillance.”

In fact, PEN is not ignoring those other issues – far from it, as demonstrated by, for instance, the English branch’s campaign for reform of British surveillance laws, and its petition in response to the seemingly dire state of things in Mexico. It’s chosen, on this occasion, to emphasize the “courage” of those whose views may be “shocking, disturbing or offensive” over “progressive” ideals – but alongside the courage of others. Suzanne Nossel, the executive director of PEN American Center, has pointed out that the imprisoned Azerbaijani journalist Khadija Ismayilova is also to be honoured this year.

What kind of speech we’re defending ought not to matter in such debates; but this latest spat suggests that it’s impossible to avoid getting into arguments about exactly that. Charlie Hebdo is now globally notorious for one aspect of its satirical work, which its detractors deem to be hate speech – for better and for worse, however, hate speech is as much a form of expression as, say, keeping a diary, and many people believe we have a “right” to do one as well as the other. (That’s a noble notion; but is it one for which human history has shown much respect?)

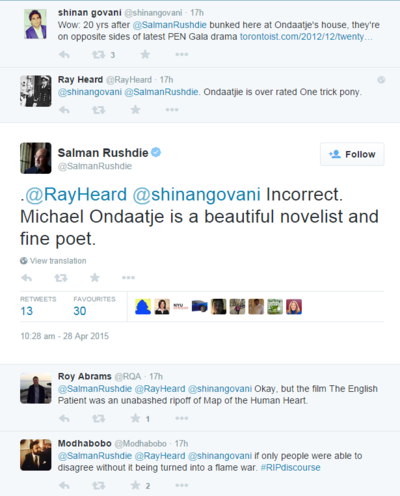

So here’s an insoluble and perhaps inevitable problem when it comes to defending free speech: it can mean defending not only the imprisoned Syrian journalist Mazen Darwish but expressions of “cultural intolerance”, Kushner’s phrase for what Charlie Hebdo does. And it’s unfortunate that disagreements about a point of principle can collapse so easily into something else, as in Boulton’s blurted-out swipe at Carey. When faced with a remark of a similar nature on Twitter, Rushdie was obliged to defend Ondaatje as a writer, his point being at risk of disappearing in the frenzy of tweeted vituperation:

In the future, I wonder, will those six writers be seen as brave for stating their views? Or will history side with their furious detractors? And lost in the middle, how many are there whose quandary is more like that of Michael Greenberg, who reported in the TLS on attending PEN American Center’s Festival of International Literature in 2006, and found himself caught between irreconcilable view on the small matter of a literary event co-sponsored by the Israeli government. The Lebanese writer Elias Khoury made an announcement that was "greeted", Greenberg recalls, "with thunderous applause, spiced with whistles and hoots of approval":

"A strange paralysis comes over me. If I refrain from applauding, I imagine, I’ll appear to be on the side of those who support Israel no matter what. If I do applaud, who knows what vindictive forces I’ll be joining. Maybe the cheers are no more than a naive wish by the audience to feel that literature and the cause of the dispossessed are the same. Yet why so much glee for what, at the very least, is a setback for a festival that seeks to promote international fellowship?”

April 24, 2015

Physical Graffiti remastered

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Led Zeppelin recently released a fortieth anniversary edition of their 1975 double album Physical Graffiti, remastered and produced by the band’s guitarist and keeper of the flame, Jimmy Page. Even those who don’t consider themselves acquainted with the album (and I concede that Led Zeppelin may not be to everybody’s taste . . .) will surely be familiar with at least one song from the album, “Kashmir”, that swirling, Eastern-inspired trip to “My Shangri-La beneath the summer moon”. The lead singer Robert Plant called it “the definitive Led Zeppelin song”.

So why the remastering?

Well, apart from anything else, the sound quality is of course enhanced. Anyone who found themselves unable to listen to the record on their Walkman will now be able to do so, sumptuously, and be reminded of what makes Led Zeppelin without rivals among rock bands (dread term). From the thunderous opening riff of “Custard Pie”, it comes over (very) loud and clear. And having spent several years putting the record together (some of the material dates from 1971), why would Page not want to see it newly available at its best?

The Daily Telegraph’s critic Neil McCormick, who is clearly a fan, captured the band’s enduring qualities in a few vivid phrases in an article last year. He describes the double album as "crammed with flamboyant, exciting, adventurous music by a group overflowing with ideas and thrilled to shoot off in multiple directions".

Rolling Stone magazine, in placing the record at no 73 in their 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, called it [Led] Zeppelin's most eclectic album, featuring down-and-dirty blues (‘Black Country Woman,’ ‘Boogie With Stu’), pop balladry (‘Down by the Seaside’) and the 11-minute ‘In My Time of Dying.’ An excessive album from the group that all but invented excess”.

I’m not sure about “excessive”: expansive, perhaps, and lush, and thrilling. Were it just a case of gross excess, the music would be of little interest. Indeed, Plant has described the album as representing the band at its most creative and expressive. For Page, meanwhile, it’s a “high-water mark”. To illustrate the range of musical styles on display, here is a list of the instruments deployed (involving plenty of overdubbing):

Drums and percussion – John Bonham, who succumbed early to alcoholic excess (like his equally talented contemporary, The Who's drummer Keith Moon)

Bass guitar, organ, acoustic and electric piano, Mellotron, guitar and mandolin – John Paul Jones (I hadn’t realized until recently that he had wanted to quit the band and take up a position as choirmaster at Winchester Cathedral before the album was recorded)

Electric, acoustic, lap steel and slide guitar, mandolin – Jimmy Page

Harmonica, acoustic guitar – Robert Plant

(Not forgetting the freewheeling Ian Stewart, occasionally of Rolling Stones fame, on piano for the frolicky “Boogie With Stu”)

The second CD of the album is, if anything, better than the first, containing that wonderful triptych “Down by the Seaside” (“Sing loud for the sunshine, pray hard for the rain . . .”), the majestic “Ten Years Gone” and “Night Flight” (“So I said goodbye to all my friends / And packed my hopes inside a matchbox . . .”). Nothing excessive here.

And then there’s the album’s famous cover image (above), designed by Peter Corriston, of the New York City tenement block with the letters spelling “Physical Graffiti” appearing in the windows.

John Paul Jones, Robert Plant, Jimmy Page and John Bonham - Caitlin Mogridge/Getty

And what of the surviving band members? Plant, who is sixty-six,hasn’t been idle. Some will recall with affection his heartfelt collaboration with the bluegrass singer Alison Krauss on Raising Sand (2009). More recently he teamed up with some very proficient musicians to record Lullaby and . . . the Ceaseless Roar (2014). And he’s performing: my thanks go to my esteemed collègue Michael Caines for taking me to hear Plant and his band perform songs from that album (and one or two older ones) at the iTunes Festival at the Round House last September. Quite an evening.

Plant has resisted all overtures to reform the band, to the apparent frustration of the seventy-one-year-old Page, who has declared himself ready to tour. It looks as though the remasterings (in 2003 Page brought out How the West Was Won, a triple live CD of two concerts in California in 1972) will have to suffice.

Trollope at 200

By MICHAEL CAINES

After the death of Rupert Brooke, commemorated on April 23 – although possibly this is to state things the wrong way round, at least in chronological terms – comes the birth of Anthony Trollope, who was born on April 24, 1815.

Both are given due critical attention in this week’s TLS (see the cover, above); it seems to me that there’s a connecting intellectual thread between them, in the form of the notions of Englishness that they seem to represent, or have been made to represent. . . .

In the post-war years, for example, Brooke was made to play the tragically short-lived Soldier Poet of myth – a matinée idol in verse. The mischievous authors of Fifty Works of English Literature We Could Do Without suggested that Trollope was meanwhile being served up as a safe cultural replacement for Jane Austen:

“Trollope is that nice, maundering spinster lady with a poke bonnet and a taste for cottagey gardens whom superficial readers thought they had got hold of when they had in fact got hold of the morally sabre-toothed Jane Austen. . . . it was not until the 1939–45 war that he became a popular (indeed, a paperback) novelist. Perhaps it was then that the English middle classes discovered that Jane Austen was not what they had supposed and took to Trollope in her place . . . .”

The waspishness of such criticism has its appeal (how pleasant it is when you’re not stung yourself), but it ignores the fact that readers are quite free to enjoy both Austen and Trollope for their different qualities. Trollope himself was modest in his estimation of his own work – lofalutin, even – and full of generous praise for Austen, conveying admiration rather than rivalry, even of different leagues rather than close competitors.

In his essay “On English Prose Fiction”, Trollope describes Austen as “surely a great novelist” – that “surely” implying that he cannot take that fact for granted as he addresses his contemporaries. Nor can he assume that they are all familiar with her novels, and he urges them to read her to enjoy, among other things, her “comedy of folly”. In that regard, he could say, “I know no novelist who has beaten her”. As Matthew Ingleby shows in this week’s TLS, there are comparisons to be drawn between them – but is it is really a case of either/or? Call me greedy, but I prefer both/and.

On looking back through the Barchester books, and leafing through the many short stories I’ve never read before, in preparation for the latest episode of TLS Voices, what I've noticed most often might be described not as the comedy of folly but the comedy of pride. (TLS Voices, incidentally, passed its first anniversary recently; how young it is.) Early, ticklish stories such as “George Walker at Suez”, “Relics of General Chassé” and “The O’Conors of Castle Conor, County Mayo” involve fits of farcical pride brought low, just as those proud Barsetshire clergymen have to jostle for the reader’s attention against one another, and against Mrs Proudie and Wilfred Thorne, Esq.

The first line of Trollope’s fortieth novel, Dr Wortle’s School – once singled out by the TLS’s former poetry editor Mick Imlah as “the fastest-written of all novels of lasting worth” – cuts to the chase: “The Rev. Jeffrey Wortle, DD, was a man much esteemed by others – and by himself”. There is nothing dignified and Darcy-ish about such formidable self-regard.

In the meantime, Trollope had been, like Dr Wortle, a man of “two professions”, and wrote his books while working for the Post Office, over the best part of four decades. How he did that, and his industrious, demystifying remarks about writing (would they have sounded better coming from, say, Joyce Carol Oates or Georges Simenon?), is something we cover in this episode of TLS Voices, while John Sutherland also writes this week about the unstinting productivity of Trollope’s last years, and Gerri Kimber reviews the new Oxford edition of Trollope’s Autobiography.

Elsewhere, bicentenary celebrations are under way or coming soon, in the form of a “Big Read” of Barchester Towers, a talk and conferences and evensong at Westminster Abbey, where Trollope belatedly received some recognition in Poets’ Corner, a theatrical adaptation of Lady Anna, and more. And while Maggs have been busy cataloguing the Schroder collection of Rupert Brooke, Joshua Clayton has compiled an impressive catalogue of first editions, and other delights, for the nineteenth-century specialist bookseller Jarndyce.

You may wish to look away at this point, if you’re neither a book collector nor related to one:

The Jarndyce catalogue begins with two letters not found in the Letters of 1983, concerning Post Office preferment and an unspecified problem concerning the name of Saint Pauls Magazine, of which Trollope was to be editor. For deeper-pocketed types, there is The Warden (“scarce” in the original cloth, £3,500) or the uniform twenty-seven volumes of the Works that have perhaps come from Easton Neston, that splendid folly of a family seat in Northamptonshire sold a decade ago to the fashion designer Leon Max (original uniform olive green cloth covers, £850).

A manuscript page of Castle Richmond, dated May 5, 1861, will set you back £2,500; it’s £1,500 for The Fixed Period, the euthanasia-espousing exercise in science fiction set in “Gladstonopolis” mentioned by Professor Sutherland. Gratuitous mention must also be made of a gift copy of The Golden Lion of Granpere from Geoffrey Keynes to G. E. Moore’s wife Dorothy (£350), merely because Keynes’s name cropped up yesterday, too – and of the second edition of Kept in the Dark at the same price, because it seems to have eluded the redoubtable collector Michael Sadleir, and indeed all library catalogues bar that of the National Library of Scotland.

At less alarming prices are the volumes on offer here from Trollope's mother Frances and his brother Thomas Adolphus; the aspiring collector could also pick up a late nineteenth-century copy of The Small House at Allington for £40, Lady Anna for £30, Trollope’s brief study of Thackeray for £20 (notable for its tutting over Thackeray’s transcription of the Irish accent and habit of being late with his “copy”), or the Trollope Society's illustrated edition of Hunting Sketches for a tenner.

The abundance of cheaper twentieth-century editions shows that, for all that the critics have always been ready for Trollope to dwindle into oblivion, either relishing or lamenting the prospect, demand seems to have kept up for new editions of oddities and entities as well as for the more obvious Barchesters and Pallisers. It bears little resemblance to the half-patriotic, half-prurient cult of Brooke, but the cult of Trollope perhaps has more persistent, happier life in it yet.

April 23, 2015

Rupert Brooke’s return to Cambridge

By MICHAEL CAINES

Oh! Death will find me, long before I tire

Of watching you; and swing me suddenly

Into the shade and loneliness and mire

Of the last land . . . .

*

I said I splendidly loved you; it’s not true.

Such long swift tides stir not a land-locked sea. . . .

*

Unkempt about those hedges blows

An English unofficial rose;

And there the unregulated sun

Slopes down to rest when day is done . . . .

Rupert Brooke, the poet responsible for these effusions, died one hundred years ago, on April 23, 1915; on his way to war, he was killed not by sunstroke (as initially reported) or syphilis (as later theorized) but septicaemia, and was buried on the Aegean island of Skyros. And with his death, the myth of the doomed soldier-poet was born. Perhaps it had already begun, as far as the wider public was concerned, with the quotation of “The Soldier” in the Easter sermon given by William Inge, Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral, on April 4, 1915. As William Wootten notes in this week’s TLS, it was a poem the Dean must have first come across in a review by Walter de la Mare in this paper . . .

A century on, Wootten revisits Brooke’s poetry, considering what might have been, had the poet lived into the age of The Waste Land, or even through more of the First World War, and what he really did achieve, mythological status aside. Are there signs of a “mature war poet”, one to be ranked with the other witnesses of the Western Front, anywhere to be found in his extant works? Seeing what he did write, Wootten asks, “Could Brooke have moved on?”

What he did write was enough for many. Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty and instigator of the Gallipoli disaster that Brooke’s death en route spared him from seeing, wrote:

“The thoughts to which he gave expression in the very few incomparable war sonnets . . . will be shared by many thousands of young men marching resolutely and blithely forward into this, the hardest, the cruellest, and the least-rewarded of all wars that men have fought.”

(It was also Churchill who had secured Brooke his commission as a sub-lieutenant in the Royal Naval Division.)

Friends and admirers returned to Skyros long after the war was over, in 1931, to commemorate him with a monument, by which time the myth-making about this young Apollo – this “King David, or Lord Byron, or Sophocles”, as Gwen Raverat mockingly put it – had thoroughly obscured the more dubious aspects of his character and secured excellent sales for his posthumously published poems. (My 1934 copy of the Complete Poems shows that demand called for a fifth impression within two years of the first; for some reason, a bookmark seems to have found a permanent home here, next to “The Hill” and its simply but effectively delayed volta.) From the TLS archives, you can also find on our website Elizabeth Lowry’s account of Brooke hagiography and the subsequent biographical turn towards iconoclasm.

Could that trend go any further? Would-be debunkers will undoubtedly find today’s announcement from Cambridge of interest: the “last great collection of Rupert Brooke manuscripts in private hands” is destined to go to King’s College, of which Brooke was a Fellow. Destined, that is, assuming the asking price can be met for this, the John Schroder collection, which includes some 170 items by Brooke himself: the college is seeking a further £70,000 to add to the grant of £430,000 from National Heritage Memorial Fund. Anybody who wishes to contribute is invited to contact the college library.

There is a substantial collection of Brooke papers in the New York Public Library, and a good scattering elsewhere (a parody of his much-loved Swinburne can be found at Cambridge University Library, for example). For those who like the idea of literary archives staying in places associated with their authors, however, the Schroder collection will seem to have found the right home when (let’s hope “when” rather than “if”) it does go to King’s: the history of the college’s modern archives began with a gift of Brooke papers. That gift was one outcome of the disagreements over Brooke’s legacy between his literary executor Edward Marsh and his mother Mary, and subsequently between Marsh and the literary trustees whom Mrs Brooke appointed, including De la Mare and Geoffrey Keynes.

Now the existing collection of Brooke papers is to be joined by what looks to be an extraordinary range of manuscripts and other materials – letters from Brooke to Eric Gill, David Garnett and Lascelles Abercrombie, others’ reminiscences, even theatre programmes from his student days. The bookbinder Sybil Pye’s last letter to him mentions that St Paul’s sermon: “does it lift up the heart to be made the text of an Easter sermon? I think my ambition would be satisfied”. Brooke warns a close friend, meanwhile, that “America is no place for a gentleman”; and his close friends in turn talk about him, up to and after his death at sea.

The Maggs catalogue of Schroder’s collection also shows how Keynes, after Marsh, was not adverse to a spot of airbrushing when it came to editing Brooke’s letters. A rather too frank reflection such as “I think I’ve been doing too much fucking”, about his sojourn in Tahiti, obviously had to go.

Skyros sees another Brooke-commemorating ceremony today, among the other celebrations promised over the next few days. Perhaps somebody will echo Churchill echoing Hamlet, after he heard of Brooke's death: “We shall not see his like again”. Such sentiments are said to have their times and places; but the Schroder collection, like William Wootten’s essay in this week’s TLS, tells a more complex story. The weary myth probably doesn't require debunking all over again – what will emerge in its place?

April 18, 2015

Portrait of the book reviewer as a prematurely aged hack

By MICHAEL CAINES

A thought for anybody planning on reviewing a book (or two – or why not three?) this weekend: among his other achievements, George Orwell is perhaps responsible for what must still be one of the best things ever written about the grind of being a regular book reviewer. "Confessions of a Book Reviewer" was first published in the Tribune for May 3, 1946; and while it is not exactly what the title promises, some of it is, I suspect, still eerily relevant to the world of the books pages . . .

Orwell himself, as noted at the foot of the Orwell Prize reproduction of "Confessions", reviewed around 700 books, plays and films over two decades, for the Observer, the Listener and even, on a few occasions, for the TLS. He peaked in 1940, "when he reviewed 135 books, plays and films in 67 reviews".

Six years later, he could refer in his short essay (highly recommended if you haven't read it before, not least as a taste of Orwell's still entertaining journalism) to the "regular reviewer" as "anyone who reviews, say, a minimum of a hundred books a year". Many editors relied then as they do now on a "team of hacks", despite the consequent devaluation of the critical language ("as soon as values are mentioned, standards collapse") and the disingenuous praise doled out by those who are doomed to having a "professional relationship" with dull books (i.e., the majority).

Alternative schemes, such as turning to a wider pool of experts and amateurs rather than the "bored professional", in Orwell's eyes, are impracticable: "that kind of thing is very difficult to organize". (At times, I'd be inclined to agree, but as it happens, barely anybody writes week in, week out for the TLS, which draws on academic experts, crack-shot amateurs and even the odd seasoned old pro.)

Orwell regards the "usual middle-length review of about 600 words" as "bound to be worthless", and 1,000 words as the "bare minimum", with "very long reviews" the ideal; I like a long essay, too, but the worth of a piece of less than 1,000 words seems to me to depend entirely on who's writing it and what it's about. How about this Guardian review of After Birth by Elisa Albert, for example, by my colleague Roz Dineen, or Janette Currie on The Old Straight Track by Alfred Watkins, both of which split the difference between Orwell's worthless 600 and "bare minimum" 1,000?

Orwell also recommended that literary papers just "ignore the great majority of books". It is tempting to take that suggestion as a sign of more innocent times – times when it seemed even vaguely possible, in the dented war years and their immediate aftermath, to cover anything like a majority of books published. There is, notoriously, little danger of that today. While many literary editors remain rightly keen to represent the diversity of what gets published, nobody can cover more than a probably much-better-than-average fraction of even just the new novels published each year. Publishers Weekly performs a useful service for the trade in covering so much ground, but obviously that has to take the form of the "Short notes" Orwell approved; learned journals that ask an (unpaid) scholar to round up, say, the year's work in Shakespeare studies are another story.

"Confessions" feels to me like a tribute to George Gissing, an updating and an aside to New Grub Street, in which reviews serve the blithely careerist Jasper Milvain as a means to achieve his ultimate strategic end, and Edward Reardon languishes in the hellish cell of his blocked, bill-beleaguered mind. Orwell's archetypal (male) reviewer occupies another sorry dwelling: a "cold but stuffy bed-sitting room littered with cigarette ends and half-empty cups of tea"; he has misplaced both his spectacles and a cheque for two guineas; he is thirty-five "but looks fifty". He has until the following midday to write 800 words on five volumes that do not, as the editor suggested, "go well together"; one of the books, A Short History of European Democracy, is 680 pages "and weighs four pounds".

To some reviewers, that will sound like the stuff of nightmares indistinguishable from the stuff of desperate days in front of the laptop (and there another small difference, the technological one, comes between Orwell's day and the present). Does it appear ridiculous to others? Indulgent and melodramatic? Accurate for its time but irrelevant now? I'd love to know.

Reproduced above and below are examples of an innovative approach to reviewing books from the self-taught comic artist Kevin Thomas, who published a series of comic strip reviews on The Rumpus from 2010 to 2014 (and which he has now brought together in book form, as Horn!: The collected reviews). Thomas describes it series as the "partial diary of a reading life", in which he tries to "get to the core of a book" and "luxuriate in its surface beauty" at the same time. It's lucky for him he quit before A Short History of European Democracy hit his desk.

April 17, 2015

In The Spectator?

By PETER STOTHARD

A call from Oxford: why am I writing about Roman toilets and sewers in The Spectator rather than the TLS.

The answer is not that the Editor of the TLS deems his readers too sensitive to read about Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow's book, or about her opening citation of Ovid's advice that a good way to cure a young man in love is to arrange for him to see his girl on the toilet.

No. The truth is that he did not expect his dear friend and colleague, Mary Beard, to have already 'sent out' the book (as we say) to someone else, in this case to the distinguished ancient historian, Greg Woolf, whose verdict will appear in the TLS in the coming weeks.

This was entirely the Editor's own fault - but it seemed a shame to waste 'the copy'. Perhaps other papers will consider this fine book. Or not.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers