Peter Stothard's Blog, page 22

July 27, 2015

Bardolatrous Boris

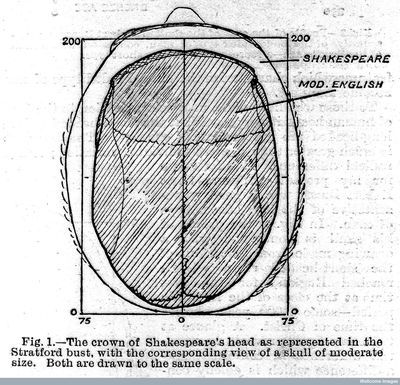

Diagram comparing the skulls of Shakespeare and modern man. Wellcome Library, London

By MICHAEL CAINES

The news that Boris Johnson is to write a biography of Shakespeare has not been greeted with universal joy. As the Sunday Times reported yesterday, the Mayor of London and MP for Uxbridge and South Ruislip is to write the book promptly, for a mildly impressive sum of money, in time to be published next year ��� the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's death. And why not? Johnson's most recent biography, The Churchill Factor, is deemed to have been a commercial success: it has sold some 160,000 copies. Never overawed by such footling matters, the TLS called it "a jaunty, opinionated and ahistorical piece of hagiography". (Ah. That's why not.)

That's also pretty much what we can expect from Johnson's Life of Shakespeare, isn't it? Johnson has given us plenty of warning, in any case: he's already written at length about the man he has called "the world's top author" . . . .

And a characteristically jaunty piece of work it is, too. Johnson's Life of London: The people who made the city that made the world appeared a few years ago, in 2011. As Leo Hollis observed in his TLS review, this earlier book is a collection of potted biographies that "collectively . . . tell us as much about the author as they do about the city". Their subjects are "rugged individualists" and mainly male. Churchill is in there, just before Keith Richards. Boudica precedes Hadrian and Alfred the Great.

When it comes to Shakespeare, Johnson tells a few of the old stories ("Richard Burbage famously fixed an assignation with a female fan at the stage door, and went to change from his clothes, only to find that Shakespeare himself had got there first . . .") ��� and issues the few facts. Many details in Life of London are drawn from a single source, Stephen Inwood's History of London: one of them is an anonymous observation about the "greatest part" of Londoners in Shakespeare's time being neither "too rich" nor "too poor", wrenched complacently out of context to imply some reassuring continuity between us (modern) and them (Elizabethan).

Johnson also draws admiringly on James Shapiro's 1599 for a thrilling sense of Shakespeare's plays as viscerally alive to their political moment, in place of that square old notion that they are "deracinated masterpieces bequeathed to the human race by some garret-bound egghead with a bad haircut" (a very fair point: not every great writer can be blessed with a Johnsonian crown of gold).

Then there are the more personal touches. Johnson reminisces about seeing Shakespeare's Globe for the first time and being stunned by the absence of seats ��� and about witnessing, as a schoolboy, a recital of Shakespeare speeches in "Brezhnev's Moscow", "watching hundreds of wrapped-up Russians stream into some dim and grimy theatre". The standard export-based model of Bardolatry naturally emerges from the latter story: Johnson's Shakespeare is "the greatest hero and ambassador the English language has ever known", "our single biggest cultural contribution to the world, our riposte to Beethoven and Michelangelo . . . . He is the one author we can truly call universal. He is our Homer".

So brace yourself for more of that.

Whoever writes it, Shakespeare's biography has always been a tricky business. In some ways, the challenge it poses is little changed since the days of Nicholas Rowe, whose dubious, influential "Biographical Account" first appeared in 1709.

In Shakespeare's Lives (1991), after surveying the biographical writings of the past four centuries, Samuel Schoenbaum could write that the twentieth century "lacks an authoritative Life [of Shakespeare] conceived in the modern spirit". Schoenbaum wondered if such a thing was even possible. The "biographical tradition" had reached its heights with the monumental efforts of Edmond Malone, J. Halliwell-Phillipps and E. K. Chambers ��� and they had all abandoned the idea of writing a "continuous narrative". Long before electronic resources made it easy for many people to say this, they had accrued too much information.

Yet Schoenbaum acknowledged that scholars would continue trying to supply just that. The twenty-first century has already given us plenty of attempts, several of them ingenious and engaging; Johnson's researchers could do a lot worse than look up The Lodger by Charles Nicholl, Ungentle Shakespeare by Katherine Duncan-Jones and the "critical biography" by Lois Potter.

Gaps in the record (those pesky lost years) and uncertainties of interpretation (country boy or sophisticated city dweller?) pose the same tempting challenges to all. Literary scholar, professional biographer and flaxen chancer alike must rely on the same basic information and resort to some degree of informed speculation. "Restless under the constraints of the historical record, biographers end up telling us about many things besides Shakespeare", Graham Holderness notes in Nine Lives of William Shakespeare (2011), "and filling the empty spaces with their own preoccupations." Shakespeare's marriage to Anne Hathaway, for example, "can be interpreted in diametrically opposed ways".

Some biographers have turned this inevitability into a creative opportunity (Stephen Greenblatt and Holderness himself come to mind) and this tradition goes back to Rowe, too, I think (perhaps because of re-reading Rowe while writing a paper for this conference about Shakespeare and a different Johnson): after editing Shakespeare and writing his biography, Rowe wrote The Tragedy of Jane Shore, "in imitation of Shakespeare's style".

Beware, Boris: "thousands and thousands of books have been written about Shakespeare", as Logan Pearsall Smith wrote in 1933, "and most of them are mad". Schoenbaum accounts for a host of batty amateurs and lesser artists whom one can only hope Johnson hopes to imitate. For example, John Abraham Heraud gives away his misguided game in the title of his Shakspere: His inner life as intimated in his works (1865). Charlotte Carmichael Stopes and Anthony Burgess show what close acquaintances they are with their biographical subject by calling him "Will". (Cf. my own faux-chumminess at the opening of this paragraph.) Frank Harris's remaking of Shakespeare in something like his own image, in The Man Shakespeare and His Tragic Life-Story (1909), sounds like a hoot.

Or perhaps Johnson should stick to something like Burgess's practical, profitable line, as heard in this extract from a talk about Shakespeare for the Book Society of 1964: Shakespeare, Burgess states bluntly, "wrote to make money".

Now that's more like it. No man but a blockhead ever did otherwise. Even the Mayor of London knows that.

July 24, 2015

Proust's Cabourg today

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Nice coincidence, or a case of great minds thinking alike? In this week���s TLS our columnist J. C. gives a charming and vivid account of a recent visit to the Normandy seaside town of Cabourg, which was said to be the inspiration for Proust���s Balbec in his novel. The very next day I read a two-page spread in Le Monde on: the Grand H��tel in Cabourg . . . .

The article in Le Monde is the first in a twelve-part series on ���Hotels that changed the world��� (!) In common with its conservative rival Le Figaro, Le Monde finds imaginative ways to fill its summer pages (remember that France starts to shut down in late July and early August, so there is not a great deal of politics to report apart from the usual internecine battles in the Front National). The subsequent two articles, very different in tone, have been on the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, which was bombed by Menachem Begin���s Stern Gang in 1946 with the loss of ninety-one lives, and the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles, which the photographer Helmut Newton and his wife Alice Springs made their home for twenty-five years. Today���s article (which I haven���t read yet) covers the H��tel du Parc in Vichy, home to P��tain���s government between July 1940 and August 1944, while tomorrow���s will be on Nabokov���s hotel in Montreux ��� that should be interesting.

J. C. writes of how Proust would visit the hotel every summer from 1907 to 1914 ���for the sea air���. (He first visited Cabourg in 1890, with his grandmother, and again that year during his military service.) In the summer of 1914, meanwhile, Proust was one of the last guests to leave before the hotel was converted into a military hospital. Poor health prevented him from returning there after the war.

Rapha��lle R��rolle, the author of the Monde article, reveals that Proust spent 421 days in Cabourg (two months per year), which he would mostly spend in his usual room with sea view on the fourth floor of the Grand H��tel, booking out the two adjoining rooms for tranquillity. He stuck to the unusual hours he was in the custom of keeping elsewhere: rising late, not going out before mid-afternoon (to the Casino next door to the hotel), receiving young visitors in his room. And working late into the night. As the Proust scholar and biographer Jean-Yves Tadi�� wrote, ���it all began in the Grand H��tel���.

R��rolle reveals that the hotel (which has a mere seventy-one rooms, but retains its belle ��poque grandeur) is now popular with Parisians . . . and Japanese tourists. Room 414 (Proust���s room) is particularly sought after. Other rituals for Proustians include having a meal in the Balbec restaurant (which Proust would have done infrequently himself, subsisting on a diet of coffee and croissants), in the hotel. Proust called it the ���Aquarium��� in A l���Ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs. It���s now said to be very expensive.

Proust's Cabourg is popular

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Nice coincidence, or a case of great minds thinking alike? In this week���s TLS our columnist J. C. gives a charming account of a recent visit to the Normandy seaside town of Cabourg, which was said to be the inspiration for Proust���s Balbec in his novel. The very next day I read a two-page spread in Le Monde on: the Grand H��tel in Cabourg . . . .

The article in Le Monde is the first in a twelve-part series on ���Hotels that changed the world��� (!) In common with its conservative rival Le Figaro, Le Monde finds imaginative ways to fill its summer pages (remember that France starts to shut down in late July and early August, so there is not a great deal of politics to report apart from the usual internecine battles in the Front National). The subsequent two articles, very different in tone, have been on the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, which was bombed by Menachem Begin���s Stern Gang in 1946 with the loss of ninety-one lives, and the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles, which the photographer Helmut Newton and his wife Alice Springs made their home for twenty-five years. Today���s article (which I haven���t read yet) covers the H��tel du Parc in Vichy, home to P��tain���s government between July 1940 and August 1944, while tomorrow���s will be on Nabokov���s hotel in Montreux ��� that should be interesting.

J. C. writes of how Proust would visit the hotel every summer from 1907 to 1914 ���for the sea air���. (He first visited Cabourg in 1890, with his grandmother, and again that year during his military service.) In the summer of 1914, meanwhile, Proust was one of the last guests to leave before the hotel was converted into a military hospital. Poor health prevented him from returning there after the war.

Rapha��lle R��rolle, the author of the Monde article, reveals that Proust spent 421 days in Cabourg (two months per year), which he would mostly spend in his usual room with sea view on the fourth floor of the Grand H��tel, booking out the two adjoining rooms for tranquillity. He stuck to the unusual hours he was in the custom of keeping elsewhere: rising late, not going out before mid-afternoon (to the Casino next door to the hotel), receiving young visitors in his room. And working late into the night. As the Proust scholar and biographer Jean-Yves Tadi�� wrote, ���it all began in the Grand H��tel���.

R��rolle reveals that the hotel (which has a mere seventy-one rooms, but retains its belle ��poque grandeur) is now popular with Parisians . . . and Japanese tourists. Room 414 (Proust���s room) is particularly sought after. Other rituals for Proustians include having a meal in the Balbec restaurant (which Proust would have done infrequently himself, subsisting on a diet of coffee and croissants), in the hotel. Proust called it the ���Aquarium��� in A l���Ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs. It���s now said to be very expensive.

Penelope Mortimer reborn

Penelope Mortimer, 1971. (Photo by Michael Ward/Getty Images)

By LAURA FREEMAN

���It���ll be alright���, says Mrs Armitage in Penelope Mortimer���s novel The Pumpkin Eater. ���I promise you. You���ll like it when it���s born, you always do, perhaps it���ll be a boy, you haven���t got anything like enough boys . . . One more won���t make any difference, I promise you it won���t.���

Mrs Armitage, pregnant for the umpteenth time, is pleading with her husband Jake to be happy about her news. It is never quite clear how many children she has accumulated from her four marriages. They are variously a ���brood���, an ���army���, a ���bodyguard���, and a ���bloody houseful���. Her father fears she���ll come ���trailing home with half a dozen more in five years' time���. Mrs Armitage wants desperately, obsessively to have another; Jake does not.

The novel was first published in 1962 and is reissued this month as a Penguin Modern Classic. A radio adaptation will be broadcast on BBC Radio 4 next month, with Helen McCrory as Mrs Armitage. So what will it mean to people discovering it now? Is it a period piece or a fiction of enduring relevance?

Either way, Mortimer certainly tells an unsettling story. (The TLS, at the time, thought it ���claustrophobic��� and ���quite the best of Mrs Mortimer���s excellent novels���.) Mrs Armitage is coerced into having a termination by a husband who has tired of playing at domesticity. ���What joy do you think I get out of this god-awful boring family life of yours?��� he asks. ���Where do I come in?���

Mrs Armitage, who has no first name in the book, only her husband���s surname, is sent to a nursing home for the termination and to be sterilized. Mr Armitage, meanwhile, knocks up his mistress.

It ought to be a bleak book, a tale of marital misery, but Mortimer does not let Mrs Armitage get away with moping. She interrogates her character���s particular malaise with wry scepticism. She is mistress, too, of the small detail. Jake���s mistress writes to him in mauve script on mauve paper (presumably, a slightly different shade of mauve), telling us everything we need to know about her.

Fittingly for a novel about pregnancy, The Pumpkin Eater had a long gestation. On March 27, 1956, Mortimer, thirty-seven years old, married to the writer and barrister John Mortimer, and mother to six children by four fathers, wrote in her diary: ���Perhaps soon I shall begin to write another book . . . I sit in the chair and smoke and think, I can���t sit here much longer; and go on sitting. I drive to John Barnes [a department store] and walk around the bales of material, even sometimes feeling it, touching it; thinking, I know quite well I don���t want to, shan���t buy any . . . Some day I shall write about this���.

In The Pumpkin Eater, John Barnes becomes Harrods ��� a fortuitous change, with the book���s long-term popularity in mind, since one department store is long gone, but the other continues to thrive. There Mrs Armitage has a breakdown in the Linen department and has to be taken to recover in a small, private room next to Lingerie. Bed linen and lingerie: the departments are significant in a novel about early passions deadened by the responsibilities of childcare.

The novel is dedicated ���To John��� which has led to speculation about how much was autobiographical. Mortimer began writing in November 1961 and finished in the spring of 1962. During that time, she agreed to an abortion and sterilization after becoming pregnant for the eighth time (her seventh pregnancy had ended in miscarriage). Shortly after the termination, she found out that her husband���s mistress was pregnant.

To my mind, the themes of the book are as pressing today ��� in a Britain of smaller families, gender (im)balance at work, and stay-at-home dads ��� as they were then. How few we have been able to satisfactorily resolve. How many children can a couple afford? How many is too many to give each enough care and attention? Can a parent love a step-child as unconditionally as their own child? Does a man have any say in a woman���s choice to have an abortion? What if he is her husband? Tellingly, the praise of Edna O���Brien quoted on the cover of the new Penguin edition ��� ���almost every woman I can think of will want to read this book��� ��� you can also find on the back cover of Penguin editions of old.

Only this week a debate has run in the newspapers, after comments made by the comedian Jenny Eclair, about whether having a nanny makes you a less able and attentive mother. Mrs Armitage regrets that affluence brings nursemaids and nannies who take your children away and tuck them into bed for you.

Perhaps the most enduring question is: for women, can children and home be ���enough���? Or must a woman maintain financial independence and her own career? Mrs Armitage suffers an anxiety about dust, and is bored by the limited, repetitive conversation of small children. Mortimer does a fine impression of the chatter of children home from school:

���I got a green star . . . I got top in Friday Paper . . . Two of the goldfish died and a cat . . . Did you see any lions? . . . I got a green star for spelling and I got . . . Well, I got top in Friday Paper . . . What were the elephants like, did you see any lions? . . . We went to the circus, we went to the pictures three times . . . That���s where I fell down . . . Did you see any camels, then? . . . and I got a green star for sums . . . .���

And so the domestic round goes on. Mortimer hasn���t any solutions to offer, but her questions remain compelling. Of which of today���s novelists might people say the same thing, for addressing the same issues, in fifty years��� time?

July 22, 2015

Dark horses

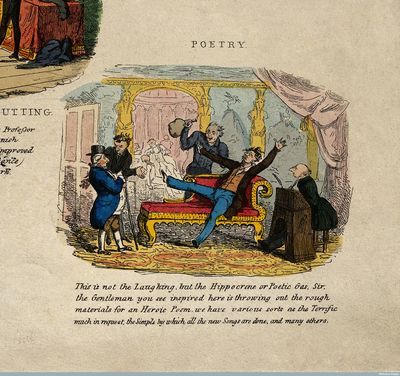

A group of poets carousing and composing verses. Coloured etching by R. Seymour after himself, 1829. Wellcome Library, London.

By MICHAEL CAINES

How many ages does a poetry magazine have? Seven would surely be too pat, an Aristotelian three ��� youth, prime, old age ��� too simplistic. The longest-lived are not necessarily the best. Poetry Review, for example, since its founding in 1912, has tended to waver in the face of experimentalism. Its longest-serving editor, Galloway Kyle, kept it going through the Second World War by taking it in a patriotic, sales-boosting direction. To a younger man, Derek Stanford, it appeared to be ���rather like an old folks' home for retired Georgian poets���.

Yes, some poetry magazines are born great; some achieve ��� but perhaps I shouldn���t be mixing my Shakespeare allusions . . . .

However many ages there are in total, Raceme is certainly in the first. Its debut issue is dated to May; three issues a year are promised. The editors, Matthew Barton and Jeremy Mulford, freely admit that they chose the botanical name ���after long deliberations���, intending to lay stress on a sense of of organic diversity and community, but only too late noticed that ���it could also be pronounced RaceMe, the name in fact of a motor-racing journal���. The poetry of the South West serves as a starting point rather than a parochial boundary; the website promises ���sequences of poems with contextual matter by the authors���, such as, in this first issue, Alyson Hallett���s ���Guadalajara Guide Book���. Barton offers a concise account of a single troublesome punctuation mark, the full stop ��� or should it be a ���Frost-influenced��� comma? ��� in Edward Thomas���s ���Adlestrop���. Philip Lyons engages in an imaginary correspondence with a certain librarian in Hull (���Dear Philip . . . Yours, Philip���), while tribute is paid at the outset to the late Anne Cluysenaar.

More Larkin lather and another homage to Cluysenaar, by Adam Czerniawski, appear in the July-August issue of the long-established PN Review ��� issue 224, or volume 41, number 6, of a magazine now in its fifth decade. Since Grevel Lindop dared to suggest in a previous issue that Larkin might not be all that, the forthright responses now published together, by Neil Powell, John Lucas and Silas Gunn, might grab the reader���s attention first. There are other kinds of dialogue, however, on show: ���The Hendonists��� by Yvonne Green, a poem ���after��� Sean O���Brien���s ���Novembrists���; Elaine Feinstein���s autobiographical recollection of her foreign, female ���poetic mentors���; Vidyan Ravinthiran on following Auden into lexicophilia; and Philip Terry���s respinning of The Regrets by Joachim du Bellay:

I���m not going to wade through creative writing manuals,

I���ve no desire to write like Larkin . . .

In this book I���ve no intention of

Imitating those who think they will live for ever

Just because they���ve had a good review in the TLS.

I was also, for some reason, taken with Miles Burrows���s wily ���Across the Road��� (���I live in a street of divorcees / Most of us are left to our own devices / Though one can be heard making love to Debussy���), and the piquant lines by Tom Pickard, quoted by Patrick McGuinness, about ���bloated tomes by toady poets who sit in circles blowing prizes / up each other���s arseholes with straws���.

Ravinthiran can also be found in the summer issue of Poetry London (first published as a ���listings newsletter��� in 1988): here his subject is Paul Muldoon���s latest collection, One Thousand Things Worth Knowing. Worth it or not, I now know that Muldoon once turned up at a conference about his work as if ���to devil us, sitting at the back of the room and paralysing the speakers into sycophancy���. And I now know what a lot of poets look like: austere within, Poetry London disconcertingly covers itself in mugshots. (I hope the intention isn���t to remind the reader that poets are people, too. We all know they���re not.)

I���m not a regular reader of the magazine, but it was good to be able to flick through this copy and find back-to-back pleasures: ���The Givens��� by Kim Addonizio ���Someone will bump into you and not apologize . . .���; ���someone will tell you / she���s sorry it���s out of her hands as though everything isn���t already���) and ���A Portable Joye��� by Stephen Knight (���along his sleeve / The infante wipeth aye his snot���). The editorial by the magazine���s co-editor Martha Kapos will interest many, since it concerns the perennial question of funding for poetry. (Is there perhaps a poetry magazine cycle dedicated to crazes, crises and life-threatening contentions?) ���Of the 664 National Portfolio Organisations that [Arts Council England] supports���, Kapos writes, ���poetry represents only 2%.��� ACE has made the ���far-sighted��� decision to train those who run Poetry London, Modern Poetry in Translation and the Poetry Translation Centre ���to become fundraisers ourselves���. All the modern questions arise here, concerning ���impact���, ACE���s alignment with government policy and its beneficiaries��� appetite for jumping through the bureaucratic hoops.

Lastly: The Dark Horse is celebrating its twentieth anniversary with a splendidly hefty issue, pleasingly printed in the traditional combination of black, white and red. Scottish poetry is well represented, of course, but the voices are many and varied, not least in the round-table discussion about anglophone poetry and criticism organized by Carmine Starnino, and in the poems by Helen Mort, A. E. Stallings, Dana Gioia and Anne Stevenson. Gerry Cambridge, the magazine���s editor, gets to play the part of the justice ���Full of wise saws, and modern instances��� in his editorial, reminiscing about the magazine���s early days (���500 copies of a slim, buff-card-covered first issue��� with a ���bumptious, somewhat prickly and combative tone���) and subsequent technological advances (���It was only when setting issue 8 that I realised how massively labour-saving e-mail was going to be���).

He also affirms the view that technology has helped to upset the ���power structures��� of contemporary poetry (���the old hegemonies seem less significant than energy, imagination and new approaches���), while railing against the ���unsensual��� ghastliness of ���on-screen reading���. Naturally, writing on a blog, I suppose I���m meant to say that on-screen reading has its uses. Those unwilling or unable to grasp the pleasure of reading verse in print might wish to consider investing in a copy of Cambridge���s pamphlet, The Printed Snow: On typesetting poetry, with its ruminations on fonts and their symbolic resonances, gutters gone wrong and who the (exceptional) good typesetters of poetry are. I suspect there are one or two poetry magazine editors who have a lot to learn.

July 17, 2015

France 1940 ��� an enduring fascination

Maurice Gar��on (Photo Henri Martinie. Roger Viollet)

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Vichy: Un pass�� qui ne passe pas was the eloquent title of a book by Eric Conan and Henri Rousso published in 1994. There���s no doubt that France in the years 1940 to 1945 exercises a particular fascination over historians, novelists and filmmakers. Added to which, we are given constant reminders of the period: on May 27, four members of the Resistance were reinterred in the Panth��on in Paris.(In an earlier post I jumped the gun by suggesting that the quartet had already been transferred there, but in fact the ceremony, at which President Hollande gave an oration, took place only on May 27.)

There are seventy-five occupants of the Panth��on. Jean Moulin was reinterred there in 1964, the first member of the Resistance to occupy its marble halls (see the TLS of December 12, 2014 for Julian Jackson and Matthew Cobb's article about Andr�� Malraux's tribute to the Resistance hero). Moulin has now been joined by Pierre Brossolette, Genevi��ve de Gaulle Anthonioz, Germaine Tillion and Jean Zay. In the President���s view, the ceremony represented ���one of the most important days, if not the most important day, of [his] presidential term���.

In June, Fayard published the 700-page wartime diary of the lawyer and writer Maurice Gar��on (1889���1967). Gar��on kept a diary for most of his life but the wartime section had been kept in a cupboard by his family until recently. It���s said to be revealing and fascinating. Gar��on, who once defended the novelist and recidivist Jean Genet on a charge of theft (of a volume of Verlaine���s poetry), was well acquainted with the Parisian literary world. In the words of Fran��ois Angelier, Le Monde���s reviewer of Journal (1939���1945), the volume offers an extraordinary portrait of ���le Tout-Paris collabo���. The diary will be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS.

Last year Caroline Moorehead published a gripping account of Resistance in the Massif Central, Village of Secrets: Defying the Nazis in Vichy France. In next week���s TLS, meanwhile, there will be a short review by Moorehead of L��on Werth���s 33 Days, with an introduction by Werth���s close friend Antoine de Saint-Exup��ry. Werth (1878���1955) took part in the mass exodus from Paris in early June as the Wehrmacht advanced across northern France. 33 Days is a vivid account of those dramatic weeks. And let us not forget the not entirely successful film version earlier this year of Ir��ne N��mirovsky���s great, posthumously published novel Suite fran��aise.

The Princeton historian Philip Nord recently brought out a slim volume entitled France 1940: Defending the Republic (Yale). In September Faber and Faber will be publishing the 550-page Fighters in the Shadows: A new history of the French Resistance by the Oxford-based historian and TLS contributor Robert Gildea (author of Marianne in Chains: In search of the German occupation, 2002). And just arrived in the TLS offices is a proof copy of David Drake���s equally bulky Paris at War: 1939���1944 (Harvard, November). All of these books will of course be reviewed. The fascination endures.

July 15, 2015

What is a book?

Margaret Atwood �� Graham Jepson/Writer Pictures

By CATHARINE MORRIS

What is a book? Margaret Atwood was in characteristically deadpan form as she set about answering that question at Lillehammer University College; as I have already mentioned, she was speaking in honour of the Nobel Prize-winning writer Bj��rnstjerne Bj��rnson, and her twinklingly helpless pronunciation of his name raised not just a laugh but a round of applause.

Her lecture was in part a tour of the writing and publishing technologies she has used in her time. She was an early adopter of the personal computer (���I had to store the text of my novel on floppy disks ��� remember those? They weren���t floppy. They were square. [You could store] only a couple of chapters per disk, and the disks . . . got stuck inside the computer and had to be prised loose with hair pins and paper clips���). In recent years she has experimented with online publishing platforms such as Byliner, on which writers can publish their works a chapter at a time. In the case of the novel saved on disks, was the book, she asked, the stack of disks? Or was it the text that was stored on them? Or was it the codex book that appeared later with the type set for it? And in the case of the novel she started on Byliner (she was asked why she wasn���t writing a ���real book���, so she took her four Byliner posts and went back to more traditional methods), was the book the first four episodes? Or was it the longer book? Or were they two different books?

Atwood asked other, related, questions (is an audiobook a book?), as well as going into enjoyable detail about the pros and cons of such things as typesetting softwares old and new (���Even today, words can float around and pop up like drowned corpses in the most unexpected places. I have just been correcting galleys for my forthcoming novel. Why did the word ���shoe��� suddenly appear in the middle of an otherwise footless sentence?���). She also reflected on the origins and function of storytelling (if you are told the story of how gazelle were successfully hunted last year, you'll have the edge when it comes to hunting them this year, and so on). ���Inside every one of us there���s an artist of some sort", she said. "Maybe not a very good artist ��� I as a painter am to Rembrandt as brushing your teeth is to dentistry ��� but an artist nonetheless."

Atwood recently became the first person to take part in Katie Paterson���s Future Library project based in Oslo; every year for a hundred years a well-known writer will submit the manuscript for a book that will be withheld from publication until 2114. (A forest has been planted that will supply the paper on which all the books will be printed.) ���How should I address these unknown readers?���, she asked. ���How will I explain to them about such things as floppy disks . . . . How old-fashioned will they think me? . . . . What will they be able to understand of my world, and how will the meanings of words have changed?���

By the time she returned to her central question, her focus had shifted. When you read, ���the brain works hard���, she said. ���Your Mr Darcy is different from my Mr Darcy. Mine does not have a wet shirt. Your Don Quixote is not the same as mine, though they may share some features. Each reading of a book . . . is unique���. So the meeting of reader and writer ��� the mingling of voices and imaginations that can take place across cultures and even across centuries ��� ���that is a book���.

July 10, 2015

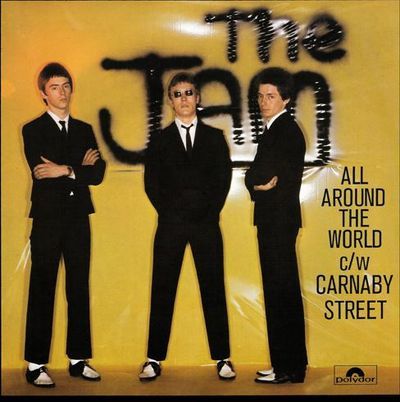

'All Around the World'

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Who���d have guessed that The Jam would end up in the grand halls of Somerset House? That���s the venue for About the Young Idea, a small exhibition on the career of one of the UK���s most successful bands of the late 1970s and early 80s (on until August 31).

The Jam, from Woking in Surrey, weren���t punks; nor were they Mod revivalists as they were once accused of being ��� the lead singer and guitarist Paul Weller objected that he could hardly be a ���revivalist��� at the age of eighteen. They were simply them: writers and performers of tight, tough, politically engaged, anti-Thatcherite three-minute songs. They rode along with the punk movement, and were caught up in it, but they always had a distinct identity, as a sharply dressed trio. (Weller, the youngest, was the leader and songwriter; the other two were Bruce Foxton on bass and backing vocals and Rick Buckler on the drums.)

Some of those early songs, the debut ���In the City���, ���All Around the World���, ���Going Underground���, still sound pretty fresh today. As does the menacing ���Down in the Tube Station at Midnight���, for all its clunky occasionally comical lyrics: ���They smelt of pubs / and Wormwood Scrubs / and too many right-wing meetings���. And personally I don���t buy the line ���the wine will be flat and the curry���s gone cold���. Wine, rather than beer, with curry? Urghhh.

When he was still Leader of the Opposition, David Cameron talked about how he used to listen to The Jam���s ���Eton Rifles��� at school (���I was one���). It always struck me as a vaguely incoherent song (���What chance have you got against a tie and a crest?���), but it clearly had a protest message of sorts. It doesn���t surprise me that it could have been appropriated by those it was supposedly attacking ��� and, of course, Cameron was perfectly entitled to listen to what he chose, even if Weller expressed surprise at reading about it.

The Jam broke up acrimoniously in 1982 as Weller wanted to pursue a solo career, which he does to this day. There have been some high points, including the Style Council���s soul-funk ���Long Hot Summer��� (1983). And the solo Weller single ���The Changingman���. Are he and Bruce Foxton now on speaking terms again?

On YouTube you can hear The Jam being hosted by a rather camp Marc Bolan on his new television show, in 1978. It's great.

July 9, 2015

Fair-weather Federers

A woman hitting a tennis ball. Photogravure after Eardweard Muybridge, 1887. Photo: Wellcome Library, London

By MICHAEL CAINES

I recently reviewed a book about tennis in the TLS: William Skidelsky's Federer and Me. Unlike most other top players, I confidently noted, the great Roger Federer plays his backhand shots single-handed. (It's not necessarily a lesser shot than the double-handed alternative, and it's certainly more versatile.) Sure enough, I then found out, Federer had improvized this two-handed lob at the French Open.

Cue a colleague of mine crafting an eerily convincing fake letter for publication, supposedly from a professor of literature who had pinpointed all the occasions down the years when the same thing had happened: "Sir, ��� I write to complain . . .". I admit it, I was taken in . . . .

The capacity to surprise has always been a part of Federer's game. Hence "How do you hit a winner from that position?", the John McEnroe question asked of a similarly out-of-nothing shot, and quoted by David Foster Wallace in a celebrated essay about the "religious experience" of watching Federer play. At the time of writing, it seems fairly certain that the brilliant Serena Williams is going to win the women's singles title at Wimbledon. The men's? It's marvellous, I think, not to have a clue.

Those ecstatic heights of gawping at the Grand Slam professionals contrast with writers' fondness for turning the sport into something else: a metaphor for fortune or love, perhaps. "Man is a tennis court: his flesh, the wall", the seventeenth-century poet Francis Quarles observed, with "real tennis" in mind rather than, prophetically, the modern version of the game, "The gamesters God and Satan; the heart's the ball."

E. M. Forster gave the game a significant, relationship-defining role in A Room with a View, and for W. Somerset Maugham, in "The Facts of Life", a young man's aspirations towards professional status have unexpected consequences. There is no shortage of further instances, reflecting the spread of the standard game over the past century or so.

Metaphors and novelistic situations aside: it's summer. In England, these are what J. P. Donleavy called the "tasty days of the Lawn Tennis Championships": "The stadium looms dark green and ivy clad, holding rich hearts, eager hearts and my own grey one shortly arriving". "Applause flutters onto the open air", Robert Wallace notes of an American tournament held in the same season:

like starlings bursting from a frightened elm,

and swings away away across the lawns

in the sun's green continuous calm

of far July.

("A Snapshot for Miss Bricka Who Lost in the Semi-Final Round of the Pennsylvania Lawn Tennis Tournament at Haverford, July 1960")

This is the time for the fair-weather, Wimbledon-inspired amateurs (like me) to seek out the stowed-away tennis equipment, and book whatever court they can get (there's a waiting list for the club down the road from me, but the courts on the common will do very well for my own flailing efforts). And so this week's episode of our podcast, TLS Voices, is about literature and this, the really beautiful game (although the short readings here tend to the comical rather than the sublime aspect):

In fact, as Skidelsky observes, tennis can be an easy distraction for writers at any time of year. A lunchtime set with your editor or sworn rival (as in The Information by Martin Amis) apparently fits all too easily into a flexible working life. Just think: you could be working on that single-handed sliced backhand return all year round. (Although, look, Garbi��e Muguruza is playing Agnieszka Radwanska; perhaps leave the television on for just a little longer . . . .)

July 6, 2015

Language taken from life

��douard Louis, 2014. Photograph by Leonardo Cendamo/Writer Pictures

By CATHARINE MORRIS

The name Karl Ove Knausgaard cropped up a lot at this year���s Norwegian Festival of Literature (mentioned in my last post), as you might expect, despite his not being physically present, as far as I know. Admiring comments all of them. The twenty-two-year-old French writer ��douard Louis, who was interviewed by Ane Farsethaas (of the newspaper Morgenbladet) in the caf�� of Lillehammer Art Museum, said that he was not very interested in contemporary French fiction; ���when I see in Norway that you���ve got people like Knausgaard . . . I���m extremely jealous���.

Louis���s first novel, En finir avec Eddy Bellegueule (which has been translated into more than twenty languages), is about a boy growing up a downtrodden working-class village in Northern France. Eddy is gay, and is beaten up every day at school because of it. His father describes him as ���the shame of the family���. He wants desperately to fit in, but has no chance of doing so. This is very much a novel from life: Eddy Bellegueule is the name Louis himself had until he officially changed it, formally drawing years of suffering to a close.

The book illuminates the ways in which we are defined by the perceptions and words of other people (���I always had this impression that my childhood wasn���t me���, said Louis; ���it was like two realities mixed together���), and the ways in which we can escape them. As Farsethaas pointed out, it is, in a sense, a work of sociology; part of Louis���s project was to understand the system ����� ruled by machismo ����� that gave rise to his mistreatment. When he was a child he didn't take into account the kind of lives his parents had had ����� ���I would just hate my mum; I would just hate my dad" ����� and he had to learn to suffer on their behalf.

Louis observed that many of those who have written about class struggles in the past have focused on geniuses, people who were born different and do everything they can to break away. ���For me it wasn���t the case ����� I try to show almost the contrary.��� The idea that he was naturally cleverer than his sister or in some way freer than his brother strikes him as ���violent��� ����� ���we can create the differences . . . the difference for Eddy was created��� ����� and as a child he just wanted to be normal. "I absolutely wanted to be masculine, to be the most masculine"; ���my dream was for my parents not to lower their eyes when I was talking���.

He was animated on the subject of the romanticization of working-class life by those who have never experienced it (���It���s a way of telling . . . the people ���stay where you are��� . . . .���Ok, you are starving, but you are so authentic��� . . .���), and the impact of politics on the lives of those who have (���It���s not a question of words; it���s not a question of speeches; it���s a question of meat ����� how are you going to eat tonight?���). He spoke about the folly of mixing love and politics (���I would support the prisoners against the conditions of life but it doesn���t mean I would want to have dinner with [them] every day���); and about writing ����� including his influences (William Faulkner, Marguerite Duras, Toni Morrison). He said of non-autobiographical fiction, ���I just get bored. I don���t feel that I can change things���; and of style, ���You have to say what you want to say. What has not been said in the other books. And if you say different things you will always have a different kind of writing���.

Louis wrote Eddy Bellegueule to bring the French working classes into the public discourse ����� ���they have disappeared, mostly, these last years��� ����� and in particular to reproduce their language accurately, something he thinks many writers shy away from; it���s as if, he said, the process of producing literature requires the exclusion of such language.

���I have the feeling that literature was forty years late compared to art���, he said. ���I was thinking in writing Eddy Bellegueule: OK, stop using this oil paint, just take paper, just take plastic, just take glass���. Some people assume that taking language directly from life is easy, but it���s not, he said; it was the hardest part of writing the book: ���To construct it, to frame it. Which sentence do you choose? . . . How can you find a rhythm?���

Louis���s second novel, which focuses on immigrants in France, will be published in January. It is based on a four-hour conversation with an Algerian man he happened to meet, and it is 300 pages long. ���300 pages based on a four-hour conversation?���, said Farsethaas. ���You���re worse than Knausgaard.���

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers