Peter Stothard's Blog, page 20

September 11, 2015

Chateaubriand's manuscript

Detail from a portrait of Chateaubriand (1811) by Anne-Louis Girodet de Roucy-Triosson

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

If one had to think of the archetypal French Romantic writer then it would probably be Fran��ois-Ren�� de Chateaubriand (1768���1848). And I���m not just thinking of the studied pose (above). He was the author of short novels such as Atala (set in North America and notable for its sympathetic portrayal of Native Americans, and published in 1801) as well as that beautifully written study in self-absorbed melancholy, Ren�� (1802). Victor Hugo said of him ���I want to be Chateaubriand, or nothing���.

But Chateaubriand is perhaps best known now for his M��moires d���outre-tombe (available in a recent Penguin Classics abridged edition as Memoirs from Beyond the Tomb). In that book, regarded as a classic of French autobiography, and which he composed over a period of thirty years from 1811, Chateaubriand describes his lonely childhood in the Ch��teau of Combourg near Saint-Malo (to anyone who finds themselves near Saint-Malo and with time on their hands I can strongly recommend a visit to the rather forbidding property ��� vaut le d��tour), his military career, and journey to North America in 1791���2, where he was received by George Washington; his long (seven years) and rather miserable exile in England, where he taught French in Beccles in Suffolk for a time; a voyage to Jerusalem; the political career and his account of the Revolution; and vivid portraits of his close contemporary Napoleon, "whose genius he admired but whose despotism he detested���, in the words of the historian Philip Mansel, and of his entourage. As Mansel puts it, Chateaubriand was ���Royalist by birth, by conviction and by revulsion���, although he had initially welcomed the Revolution before turning against it. Talleyrand, meanwhile was characterized by Chateaubriand as ���vice leaning on the arm of crime���. Of Napoleon���s exile to the island of Elba, the author writes:

���Bonaparte had refused to embark in a French ship, setting store at that time only by the English Navy, because it was victorious; he had forgotten his former hatred, and the calumnies and insults which he had heaped upon perfidious Albion; he saw no one now who was worthy of his admiration save the triumphant party, and it was the Undaunted which took him to the place of his first exile.���

In a saga worthy of that other literary titan Balzac (who found the younger writer ���morose���), the Memoirs ��� or at least a manuscript copy of them ��� have become the subject of a legal wrangle. According to Pascale Robert-Diard and St��phane Durand-Souffland, writing in Le Monde and Le Figaro respectively (September 10), the fifty-eight-year-old lawyer Pascal Dufour was due to appear before a Paris court yesterday charged with attempting to sell the manuscript of Chateaubriand���s Memoirs at auction for between ���400,000 and ���500,000.

Thomas Samson/AFP

In 1836, finding himself in financial difficulties, the author sold the manuscript to his publishers Delloye et Sala with the proviso that it be published a year after his death ��� hence the title. The manuscript was written up by Chateaubriand���s secretary and placed in the hands of a Parisian lawyer, Ma��tre Cahouet, and into a safe with three keys ��� one in the possession of the lawyer, one with the publishers and one with the author. In 1847 the manuscript was replaced with an expanded version, which was published in 1850. The publishers were wound up shortly after and the manuscript has remained with the law firm ever since.

When Cahouet died he was succeeded by his clerk Jean Dufour. Pascal Dufour is his great-great-great-grandson (one Dufour went by the first name of Napol��on). Matters are complicated by the fact that the widower Chateaubriand died childless. State lawyers have therefore had to track down his closest known relative, one Guy de La Tour du Pin (scion of another aristocratic family), who has let it be known that he doesn���t want to press charges against Dufour, but would like the work to be returned to its rightful owner, i.e. the writer���s family.

The court will have to decide to whom the manuscript belongs; in other words, was Dufour within his rights to try to sell it, or is he guilty of an ���aggravated breach of trust���? It appears that the state has no stake in the matter: a spokesman for the National Archives has said that the manuscript constitutes a private archive rather than a national one. The verdict will be handed down ��� with characteristic speed ���- on December 10.

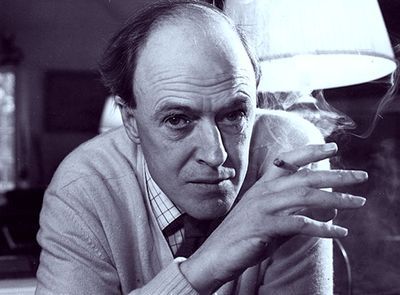

Deliciously dark Roald Dahl

Roald Dahl, 1971; Photograph by Dumant/Getty Images

By ROBERT POTTS

A couple of years ago, I purchased, at a bargain rate, a boxed collection of books by Roald Dahl, and began steadily introducing them to my young son at bedtime. So many seemed to begin with difficult material ��� the orphaning of James at the start of James and the Giant Peach; the orphaning of Danny at the beginning of Danny, the Champion of the World; the poverty of Charlie Bucket in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory; the ill-treatment of the eponymous Matilda -- that I shied away, given my son���s age, but with helpful advice from younger colleagues I began with The Fantastic Mr Fox, which merely involved three horrible farmers trying to starve or shoot a delightful family of foxes . . . .

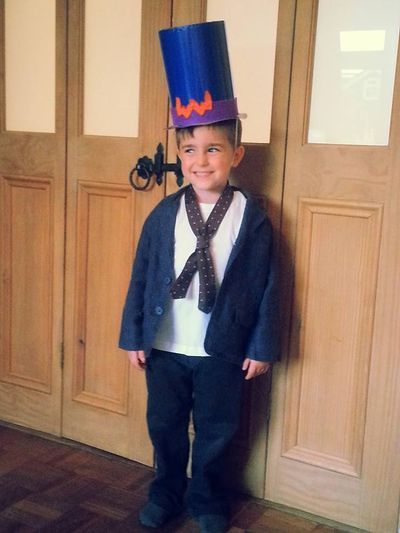

Halfway through the book, my son leaped on top of me, hugged me fiercely, and said ���THANK you! I LOVE this! Can you get MORE fox books?��� I can honestly say that I had never given so much pleasure to another human being. But my son was only experiencing what millions of other readers have discovered over the decades. Dahl is routinely listed as one of the most popular novelists in the UK, voted for by adults and children alike. On Sunday, Roald Dahl Day will be celebrated internationally; today, children at my son���s school will be dressing up as their favourite character from Dahl���s books, in anticipation.

Probably what makes Dahl popular is precisely the elements that had made me hesitate. Countless protagonists in successful childrens��� stories are orphans ��� it enables a fantasy of autonomy that children love and need. And the painful elements? Partly they initiate a dramatic arc ��� triumph over adversity ��� but more importantly, they are a way of dealing with fears and anxieties in a safe place, a fiction told by a trusted figure in the cosy haven of the bedroom. The actor Colin Baker, a former star of Doctor Who, spoke recently about how scary that programme could or should be, and cited Dahl in his assessment: ���Something Roald Dahl recognized is that children love to be and need to be frightened [in order] to understand the world around them. It���s what the Grimms��� stories were all about, they were horrible. We tend to wrap our kids up in cottonwool now, but getting kids deliciously afraid is a good thing���.

As has often been remarked, Dahl doesn���t condescend to children; he addresses them conspiratorially, life is seen from their point of view. This is thrilling and empowering for the young reader. But as a counterbalance, adult readers might enjoy this exchange in the television sitcom Outnumbered, when the Head Teacher is talking to the precocious and rebellious schoolgirl Karen.

HT: Tell me Karen, do you like Roald Dahl?

K: Sorry?

HT: Have you read much Roald Dahl?

K: When I was I younger, yes?

HT: And which was your favourite? Was it Matilda? I bet it was!

K: Yes, it was.

HT: Yes. Matilda, a very special little girl who refuses to buckle under and so defeats all those stupid grown-ups. It���s a great story. Shall I tell you something Karen, I���d ban Roald Dahl. He���s probably ruined more children���s lives than polio. Ruined them with the idea that all adults are stupid and can routinely be outwitted by small children and the occasional fox.

K: Not all of the grownups in Matilda were stupid. Her form tutor Miss Honey was nice. She let Matilda go and live with her.

HT: In the real world, dear, Miss Honey would be sacked for inappropriate behaviour. Now if you like reading, I recommend this.

K: Lord of the Flies?

HT: Yep, that���s what really happens when children get to make rules. Corpses everywhere.

September 8, 2015

Farquhar���s finest?

Pippa Bennett-Warner (Dorinda) and Susannah Fielding (Mrs Sullen) �� Manuel Harlan

By MICHAEL CAINES

A postscript to those 101 Greatest Plays: when it comes to eighteenth-century plays in English, Michael Billington understandably sticks to the conventional few comedies that are still performed today. If I were to play the same parlour game, however, I���d pick George Farquhar���s last (and now somewhat less popular) comedy, The Beaux��� Stratagem, over Billington's choice, The Recruiting Officer.

The Stratagem, as it became casually known in the eighteenth century (cf. The Dream, a current abbreviation for one of Shakespeare's most popular plays), happens to be playing at the National Theatre at the moment. It's nearing the end of its run, however, so there are only a few more chances to catch it and see what an extraordinary piece it still is. At least as refurbished, shall we say, by Patrick Marber and the revival���s director, Simon Godwin. . .

First staged in 1707, the play begins with the arrival of a very fine gentleman arriving with his servant at a Lichfield inn; in fact, they are both gentlemen, on the run from their London debts, swapping the master/servant roles as they go from one town to the next, and hoping to repair their fortunes by catching a rich widow or a naive heiress. The landlord of the inn (deliberately armed by Farquhar with the world's least funny catchphrase: "as the saying is") suspects that they are highwaymen, and has his own plot afoot; the most promising young heiress in the vicinity has a sister-in-law who ought to be a widow but is still married to a drunken husband who despises her. Farquhar famously drew on Milton's divorce tracts in dramatizing this miserable situation. "Spouse" is the monosyllable with which Mrs Sullen meets her husband at one point. "Rib", he replies, just as grimly.

Thanks to Godwin���s sharp direction, Marber���s dramaturgical interventions, the comic excellent of the cast, and especially Susannah Fielding���s moving turn as Mrs Sullen, the current Olivier Theatre production is a glorious affair. Godwin has Mr Sullen (Richard Henders) added to the opening scene, a dead-drunk adornment to welcome those debt-ridden gentlemen Aimwell (Samuel Barnett) and Archer (Geoffrey Streatfeild) to Lichfield. Pearce Quigley continues his mission to out-deadpan every actor in town; Jamie Beamish, as a priest, has to essay two accents at once.

I'd read a couple of reviews suggesting that it was in some way underpowered, lacking in life ��� if so, a metamorphosis has taken place. (Isn't it a misleading clich�� that productions tend to tail off in quality as the run goes on?) Instead, the show seems impossibly to contain a farce and a serious disquisition on the evils of matrimony, held in balance for a short time.

The action of this Beaux' Stratagem culminates in a neat improvement on Farquhar's final scene (which, I admit, after the climactic verbal duel between the Sullens, does rush a bit towards its conclusion). It also completes a transformation in Archer's personality; he's generally more roguish than his romantically inclined confederate Aimwell, and the original has him outmanoeuvre Mr Sullen and free Mrs Sullen's fortune from his clutches with a rogue's trick. While this altered ending satisfies something otherwise lacking in the play's structure, it also veers sentimentally away from the usual view of Farquhar ��� the clich�� being that he clear-sightedly draws people as they are.

Explicitly rejecting Aristotle and the attendant claptrap about dramatic theory as a guide to writing plays to please a modern English audience, Farquhar instead "developed the ability to put real characters and real situations on the stage", as Elisabeth J. Heard puts it in her study of his comedies. (I'd love to see how his neglected, earlier, darker plays, The Twin Rivals or The Inconstant perhaps, worked on stage now.) A cynic might say that real people don't undergo real reformations. Or ought a cynic just lighten up, as the saying is, and smile?

September 5, 2015

George Herbert by candlelight

By MICHAEL CAINES

If you���ve attended a poetry reading in the past, say, twenty years, you���ve probably heard it: the Portentous Hush. This is what Joseph S. Salemi, a poet and Professor of English in New York, once provocatively identified as ���the single most destructive and off-putting characteristic of contemporary confessional lyrics���: an attitude of reverence that cancels out criticism, and would merely have you listen to the recitation of morally earnest verses ���as if they were a religiously sanctioned revelation���.

���You can find Portentous Hush at every level of current poetic composition���, Salemi observed in 2001, ���from the whining of some lovesick adolescent in a collaborative workshop to the boring but well-remunerated exhalations of Diane Wakoski and Rita Dove���. Salemi is talking here about the writing of poetry, but I���ve heard plenty of poetry readings infected, in turn, by the same phenomenon ��� ���the oracular tone, the inflated self-importance, the complete failure to perceive that poetry need not be overheated vatic utterance��� ��� and seen audiences fail to respond to poets who take a irreverent, satirical line, seemingly because they don���t know that they can. . . .

At the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse last night, the Hush seemed to abate in the presence ��� of all things ��� of the genuinely religious poetry of George Herbert and a series of sensitive responses to Herbert by contemporary poets, some of them (though maybe not enough of them) written for the occasion.

This was the second in a short series called The Voice and the Echo (the next one, devoted to William Blake, is tonight, then it���s Gerard Manley Hopkins on September 9; the first event was inspired by John Donne, and included a new poem by Paul Muldoon, "From His Mistress Going to Bed", published in the TLS last month). Actors, in this case Alex Jennings and Hattie Morahan, read out the poems; the cellist Jacqueline Thomas provided apt musical interludes. This being the Sam Wanamaker, the candles were lit and lowered; a few of the Herbert-inspired poets were there to read out and elucidate their works for themselves. It was all beautifully prepared, and set up, you might think, for a bad case of Portentous Hush: Live!

Or perhaps that���s to take the religious poet tag too . . . seriously. Herbert���s devotion, his springing into formal innovation, his confessions of doubt and failure, and all-consuming conversation with God, make him not a humourless bore but a more amusing and, in the best sense, conceited writer. (Jennings conveyed that in his reading of ���The Sonne���, Herbert���s son-net piously in praise of the usual, but also in praise of the English language: ���How neatly doe we give one onely name / To parents issue and the sunnes bright starre!���)

Today���s poets, as John Greening noted before reading his own ���Near Leighton Bromswold, Huntingdonshire���, tend to write more ���obliquely��� about religion than Herbert did. For his part, Herbert would perhaps have understood us all too well: a fluent scholar, who enjoyed the best of (Jacobean) First World privileges by birth and education, and was drawn to the world of the Court and a political career (before, in one impressively wicked swoop, fate carried off his two patrons at the same time). Born in 1593, he died of tuberculosis in 1633, not long after taking holy orders and becoming Rector of Bemerton, an obscure Wiltshire village (it���s now on the cusp of Salisbury). His poetic collection, The Temple, appeared posthumously, within a year of his death. W. H. Auden reckoned him ���ingenious, though never . . . obscure���, ���capable of clever antitheses that remind one of Pope���, or even Mallarm��:

Church-bels beyond the starres heard, the souls bloud,

The land of spices; something understood.

The Voice and the Echo showed a loving but not over-sombre respect for Herbert���s poetry, helped by the rhythm it fell into: music; a male or female voice reading Herbert; the other voice responding with a modern piece of writing. Vikram Seth was present for the reading of his poem ���Host���, from a cycle of six poems written in 2007; three were first published in the TLS, with a note by Seth about the "deep affinity" he feels for Herbert. "Host", for example, recounts Seth's doubts over moving into the Old Rectory in Bemerton, where Herbert lived for the last few years of his life. As Herbert was instructed to ���sit and eat��� (at the feast of ���Love���), so Seth did find himself permitted to ���sit and write���.

In response to Herbert���s ���Death��� (which aptly followed a neat prose summary of Herbert���s Life-story), Daljit Nagra���s ���8��� imagined the deceased, were their ���punctual // heart-stop��� to be serenely timetabled and foretold by an hour, receiving visitors ���taking / turns to embrace you with private words���. (The word ���palimpsest��� ought to make its predictable entrance here.) Morahan made ���In search of sleep��� by Grace Nichols (���I took my insomnia to the sea���) sound like a very Herbert-like quest for peace, prompting a collective gasp of appreciation from the galleries; Jennings read ���Affliction (I)��� and persuaded the audience to laugh along with the perturbed lines about the poet being betrayed ���to a lingring book��� and wrapped ���in a gown���. Glyn Maxwell���s response, ���The White���, meditated on a poet���s creative progress from optimistic youth to maturity, increasingly haunted and hemmed in by the blankness around the written word. ���The black-and-white [of the inscribed page] is the creature against the Eternal���, he said. Written down, perhaps that appears portentous than it was.

Other, more lately lost poets were invoked: Lee Harwood, to whom the performance was dedicated, and Seamus Heaney. We were not, as in Nagra���s ���8���, comfortably ahead of fate this time. But there were moments of clarified peace, all the same ��� hushed for all the right reasons.

That Ferrante feeling

I have finished Ferrante. After working my way through the author���s Neapolitan series ��� the final instalment of which will be reviewed by Lidija Haas in next week's TLS ��� I found myself working back through her shorter work, in which similar themes ��� the effacement of women; transformation within the everyday ��� are explored with less range but a vivid intensity. Three novels are currently available in English (with more to come). Troubling Love concerns a daughter in the wake of her mother���s mysterious death; The Days of Abandonment follows a wife and mother reeling at the betrayal of her husband; in The Lost Daughter a woman is preoccupied by both a stranger���s loss and her own.

There is an inevitable feeling of abandonment when you finish a really good book. Everyone knows the feeling ��� at least I hope they do ��� and it speaks to the strange intimacy of the reading experience as a whole. Ferrante's voice has been with me for so long now, I feel bereft without it. Science has apparently established that reading a book stimulates the membranes in your brain (in the left temporal cortex, to be exact), so it���s perhaps no wonder I feel dulled. But where do I turn next?

It is fortunate, perhaps, that August was ���Women in Translation Month���, an initiative masterminded by Meytal Radzinski on her blog Biblibio, Life in Letters, which aims to raise awareness and co-ordinate discussions of works in translation written by women. This follows in the wake of work done by the organization Literature Across Frontiers, which has tracked the steady growth of translated titles in the UK over the past few years. And yet a report published by them in 2013 still found that only 3 per cent of books published in the UK were in translation, a figure the organization���s director Alexandra B��chler rightly condemned as ���embarrassingly low���. Currently the figure stands at around 5 per cent ��� a marked improvement, certainly, but still a meagre offering when compared to France���s 50 per cent, especially when only a third of these translated titles are by women.

Thankfully, due to recent successes such as Ferrante and Karl Ove Knausgaard, literary translation is on the rise, with a glut of small presses ��� Pushkin Press, Peirene Press, Norvik, to name a few ��� dedicated to bringing writers from around the world to an English-speaking audience. A few days ago the TLS received review copies of Donatella Di Pietrantonio���s My Mother Is a River, the first book produced by Calisi Press, a new publishing house that deals exclusively with translations of Italian fiction by women. Earlier this year, & Other Stories announced their plan to only publish translations by female authors for the whole of 2018. Ferrante has helped to create a demand not only for translation but for women in translation. With no face and no real name she has inadvertently made herself the perfect template for the overlooked foreign female author.

September 3, 2015

Michael Billington among the greats

By MICHAEL CAINES

Michael Billington drops a name at the outset of The 101 Greatest Plays: it was Antonia Fraser who suggested he adopt the superlative for his title, to "raise the stakes". Billington's book challenges readers to disagree ��� not just with his choices, but with the reasons behind his choices ��� and will perhaps inspire some to compile their own lists. . . .

Nobody has or could ever see everything. The Guardian's veteran theatre critic, however, has managed to see about 9,000 plays over the past half-century; and many of them he has written about with exemplary acuity, although, given the widely diminishing space for in-depth reviewing across the media, notably on television and in certain broadsheets, it is not certain that many will be able to follow his example in the future.

That critical experience provides the book with its USP ��� its Unique Stalls Perspective. How, after all, is a play to impress the professional playgoers? Can they be excited by the same play in a second production, once the novelty has worn off? Re-viewing, like rereading, is a good test for work and critic alike.

For Billington, moral ambivalence emerge as one common quality; as does the seeming presence of a unique authorial voice (which is especially difficult to judge, he admits, when it comes to translated works). He approves of plays that seem to absorb the past while setting their sights on the (theatrical) future. There is also the basic test of asking if a play works in different contexts, in different theatres, at different times.

Hence his provocative but not gimmicky selection from Shakespeare (Love's Labour's Lost but not King Lear) and Samuel Beckett's All That Fall rather than anything more obvious. Lear seems too much of a mess to him (whereas he rates highly the structural ingenuity of, say, No��l Coward's Design for Living or The Real Thing by Tom Stoppard) and contains "a punishment disproportionate to the original sin" (which some would say is precisely a sign of its greatness, of its refusing to yield to our intense desire for poetic justice). And he frankly admits that Beckett's general vision of life as "an irremediable hell" is not to his taste, preferring the "localised richness" and "vivid particularity" of this radio play. (He's right to point out that All That Fall has been staged, but omits that Beckett thought that was a bad idea, and usually refused permission.)

Hence also Billington's preference for plays that he's seen work not just once or twice in the theatre but several times, often to new effect each time. "I've measured out my life in Uncle Vanyas", he writes, beginning with Laurence Olivier's Chichester Festival Theatre production of 1962. The critic himself doesn't seem to have changed much at all over the years, seeming almost to distrust theatricality sometimes: he disliked the "self-advertising" National Theatre revival of Sophie Treadwell's Machinal, for example, with its "virtuosic set", much as he feels that the current Barbican production of Hamlet privileges its "visual conceits" over "textual investigation".

Indeed, the whole exercise is a homage to the "subversive voice of the individual dramatist" ��� it is dedicated to "the playwrights, living and dead" ��� and a riposte to the emerging notion that "democratising the work process" in devising a play "automatically leads to work of radical intent". Who exactly holds to that notion about devising, down to the word "automatically", is never made explicit.

With authorial subversiveness to the fore, 101 Greatest Plays pays tribute to subversive work written under oppressive regimes or against impossible circumstances. Greatness may be reserved for 101 plays, but the brief biographies here of so many exceptional dramatists open the doors to further exploration. (The contents page, incidentally, tries to get in on the act, by getting its page numbers out of sync; the reader interested in Peter Pan is decisively sent to Waste by Harley Granville Barker instead. It's not the volume's only sign of scrappy production.) For Billington, biographical and historical context matters: "our" knowledge that Federico Garc��a Lorca completed House of Bernarda Alba two months before Francoists executed him, in 1936, "informs our vision of the play". Not that such considerations outweigh all others, otherwise George Farquhar's last play, The Beaux' Stratagem, could perhaps have trumped its predecessor, The Recruiting Officer.

As that last choice suggests, predictable choices outnumber surprises here ��� but they are only predictable because of the consensus, and the consequently rich performance history, that has emerged around them. (For a less reverent alternative view of The Crucible by Arthur Miller, to take one example, see Diane Purkiss's recent TLS review of The Penguin Book of Witches.)

It is more interesting, I think, to see Billington championing Assembly-Women by Aristophanes, Venice Preserved by Thomas Otway, and Ena Lamont Stewart's Men Should Weep, which I missed when it came to the National five years ago and is one of only three post-war plays by women included here. (More happily, Congreve's Love for Love, which here wins out over The Way of the World, is to be staged by the RSC this autumn.)

Finally, from the cheap seats, it caught my eye that Billington makes room for five plays by Shakespeare's contemporaries: Edward II by Christopher Marlowe; The Malcontent by John Marston; A Mad World, My Masters by Thomas Middleton; The Alchemist by Ben Jonson; and The White Devil by John Webster. How does that strike you? I confess to finding Middleton's comedy tiresome next to the tragedies, and imagine that scholars in that field could argue for a hundred different plays, on their own terms.

All right, not quite finally. Here are the four twenty-first-century plays Billington includes: The Goat by Edward Albee; The History Boys by Alan Bennett; Jerusalem by Jez Butterworth; and King Charles III by Mike Bartlett. Could these four stand the test of time as well as, say, Uncle Vanya?

September 1, 2015

The death of Louis XIV

Louis XIV by Hyacinthe Rigaud (1701)

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Louis XIV reputedly never said ���l�����tat, c���est moi���. The phrase was first attributed to him at the beginning of the nineteenth century. He did, however, utter the sentence, almost his last words, ���Je m���en vais, mais l�����tat demeurera toujours��� (���I���m going, but the State will always remain���), His final agony lasted twenty-three days. Normally a prodigious eater, he left his food mostly untouched.

Louis XIV, le Grand, le Roi Soleil, died 300 years ago today. It���s generally agreed that he endured his suffering with courage and dignity. Even the waspish courtier and memorialist Saint-Simon conceded that in his leave-taking, Louis XIV ���presented the most touching spectacle, which made him admirable��� (���forma le spectacle le plus touchant, qui le rendit admirable���).

The historian and professor at the University of Paris���VIII Jo��l Cornette, has just published La Mort de Louis XIV: Apog��e et cr��puscule de la royaut�� (367pp. Gallimard. ���21). This fascinating book (which will be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS) appears in a series entitled ���Les Journ��es qui ont fait la France���, the day in question here being September 1, 1715. As the publishers put it, a trifle hyperbolically perhaps, ���This day was the only one over which the Grand Roi had no control, he who wanted to be all-powerful director of his kingdom���. For Cornette, ���the death of Louis XIV closes a chapter in the history of [French] royalty���. In his time the French monarchy reached the apex of its power. Yet he left behind a system of government which, according to Cornette, can still be discerned in the workings of the Fifth Republic today.

Cornette writes that during the final two days of the King���s life all the apartments at Versailles remained closed; in order better to control all information about the imminent death all mail had been stopped. By September 2, an autopsy had been carried out, followed by the process of embalming. The official funeral took place on October 23, six weeks after the body had been transferred to the cathedral of Saint-Denis (now in the northern suburbs of Paris), burial place of French kings down the centuries.

How was the death of Louis XIV greeted? Aside from the torrent of lampoons, with something between indifference and secret relief, Cornette tells us. ���The length, the weight, of an interminable reign had exhausted both spirits and hearts���. (Louis came to the throne in 1643 at the age of five, after the death of his father Louis XIII; although he came of age in 1651, i.e. at thirteen, he only assumed full powers after the death of his chief minister Cardinal Mazarin in 1661.) The priest of Saint-Sulpice, a small parish near Blois, wrote in his Remarques sur l���ann��e 1715, that Louis���s death was ���little regretted by his whole kingdom, because of the exorbitant sums and enormous taxes he had levied on all his subjects���. The only ones to profit in this subjugated, impoverished nation, he went on, were the financiers and the tax collectors. As one verse had it, ���Dans ce tombeau est inhum�� / Un roi si tendrement aim�� / Au commencement de son r��gne; / Sur la fin si peu regrett�� / Qu���on a peur qu���il ne revienne���. ���What a contrast���, Cornette writes, ���with the splendours of August 1660, when the twenty-one-year-old monarch made his triumphal entry into a rejoicing capital!���

���L�����tat louis-quatorzien��� was above all dedicated to military glory, on land and at sea. France was, it seems, in perpetual conflict during his reign: the Fronde, or civil uprisings of 1648 and 1651���3, the Dutch Wars of the 1670s. In the War of Spanish Succession between 1701 and 1714 nearly 650,000 Frenchmen were mobilized, out of a total population of 20 million. Cornette calls the French state at the time an ���insatiable Leviathan���. Yet, the defeats multiplied: Ramillies (1706), Oudenarde (1708), a costly victory at Malplaquet (1709). Added to which were the terrible winters such as that of 1693���4, during which 1.6 million French citizens perished. A further punishing winter in 1709���10 (average temperatures of ���20 degrees C in the Ile-de-France in January and February, rivers froze over and birds fell out of the sky) carried off another 630,000 citizens ��� the death toll less great this time partly as a consequence of "l'intervention de l'��tat" (which sounds like a slightly anachronistic phrase).

Religion: in his lifetime Louis heard 2,000 sermons, attended Mass 30,000 times, i.e. one a day, touched some 200,000 people afflicted with scrofula (���le roi te touche, Dieu te gu��risse���). His detestation of Protestantism, meanwhile, grew with the years. The revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 resulted in some 200,000 Huguenot Protestants choosing exile to England, Holland, or Germany, depriving his country of a valuable skilled workforce. Jansenists fared little better, being viewed as dangerous heretics; their headquarters at the abbey of Port-Royal were closed in 1710, the buildings razed to the ground.

Louis acknowledged at least twenty-two children, of whom six were legitimate. Cornette writes that there were also ���all those, numerous no doubt, of whose existence we���re unaware���. His affair with Louise de La Valli��re produced five children; only two survived into adulthood. Six of the nine children borne by the beautiful, spirited Marquise de Montespan, Louis���s mistress in the 1670s, went past the age of seven. In Cornette���s nice phrase, after the death of the last of his mistresses, Mme de Fontanges, in 1681, the King ���resolved to think about his salvation���.

The arts and learning flourished in Louis's reign. Cornette lists the bodies that were set up in that time: (the Acad��mie fran��aise had been founded by Cardinal Richelieu in 1635, three years before Louis���s birth)

Acad��mie de peinture et de sculpture (1648)

Acad��mie de danse (1661)

Acad��mie des inscriptions et belles-lettres (1663)

Acad��mie des sciences (1666)

Acad��mie de France �� Rome (1666)

Acad��mie royale de musique (1669)

Acad��mie d���architecture (1671)

Acad��mie d���op��ra (1671)

The Hall of Mirrors at Versailles

But it would be fair to say that Louis���s most visible legacy is the Palace of Versailles, much changed though it apparently is in appearance since his day. (See the American author William Richard Newton���s three-volume history, covering everything from fountains and waterworks to stables; reviewed in the TLS, March 16, 2012.) He first set eyes on the Palace in 1651 while out hunting (a pursuit he followed with a passion) at the age of twelve. The place had been more or less abandoned since the death of Louis XIII. The Court, with its attendant splendour, was transferred from Paris to Versailles (at one point Louis went four years without visiting the capital). Among the great names associated with the Court of Louis XIV are Racine, who wrote two plays, Esther (1689) and Athalie (1691), to be performed by the girls at the school of Saint-Cyr set up by the King���s second wife the Marquise de Maintenon.

On his deathbed Louis appeared to concede failings: addressing his successor, his great-grandson Louis XV (who himself came to the throne at the age of five and reigned until 1774), he said: ���Do not copy me in my love of building or in my love of warfare . . . try and improve the lot of your people, as I, unfortunately, have never been able to do���. Cornette concludes that while Louis XIV took his authority from God alone and was answerable only to Him, neither Louis XV nor the unfortunate Louis XVI was ever able to display such uncontested authority. After 1715 came the Enlightenment, and then the Revolution.

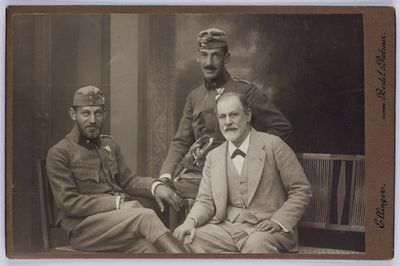

Freud's books

By BENJAMIN POORE

Earlier this year I became involved in organizing a new exhibition: The Festival of the Unconscious, at the Freud Museum in Hampstead, which runs until October 4. I was to mine Sigmund Freud���s library to see who and what he was reading as he composed key papers, in particular his ���metapsychological��� works ��� ���The Unconscious��� being the most famous of them ��� which collectively celebrate their 100th anniversary this year.

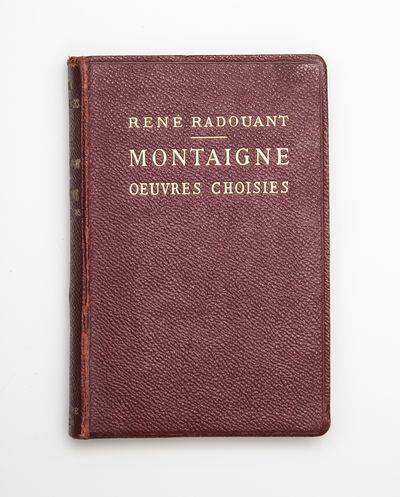

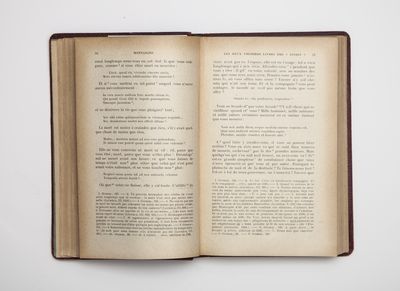

Psychoanalysis is all about the details, and so looking for Freud���s notes and annotations seemed an appropriate way to start. One of the first books I came across was his copy of Montaigne���s Selected Works, edited by Ren�� Radouant and published in French in 1914. Freud���s underlinings suggest that he was reading the great essayist in the opening years of the First World War, so powerfully do the annotations resonate with the anxieties and fears that punctuate Freud���s writing in this period.

Freud with his sons Ernst and Martin in Salzburg, 1916

Freud was hardly removed from the furious political and social upheavals of the war ��� his own sons, with whom he is pictured above, were at the Front ��� so it might seem curious that his writing is both abstract and speculative. Yet death and hostility loomed large for Freud in these years. Think of the bucolic On Transience, which featured a disguised and miserable Rainer Maria Rilke; the gloomy Mourning and Melancholia, eventually published in 1917; and Thoughts for the Time on War and Death, published in late 1915, as Freud���s initial excitement about the war soured into the prevailing cultural pessimism of his later work.

Montaigne's essay ���That to Philosophise is to Learn to Die��� is especially well-thumbed. In Radouant���s introductory rubric, underlinings and jottings point us towards the resolute stance on death taken in Thoughts for the Time, with Freud remarking: ���Montaigne refused to admit to himself that virtue could be separable from suffering���. Freud's insistence that we must take death in our stride is echoed elsewhere in his reading, too. In Montaigne���s essay itself he underscores the remark that ���the value of life is not to be found in its length, but rather its employment���.

Such marginalia offers the first indications of the ethical and moral preoccupations that war would increasingly encourage in his work. To ���bear life���, he went on to write in Thoughts for the Time, we must accept its brevity and fragility. We should, it follows, take ���the truth into account a little more���: this would make life ���more bearable again���.

Freud's copy of Montaigne forms a key section of the exhibition titled ���Reading the Unconscious���, where it joins other books on display, including collections of Rilke���s poems belonging to his daughter, Anna.

The exhibition is also traces the links between Freud���s ideas about the unconscious and contemporary scientific writing. This is particularly visible in a 1911 edition of The Grammar of Science, by the English statistician Karl Pearson. The book is annotated thoroughly, the reader's compact scribbling betraying anxieties about the ambitious nature of his own developing theories. (Pearson, like Freud, was involved in the radical political and social movements of the early 1900s, most alarmingly in his enthusiasm for eugenics.)

In Drives and Their Fates, also from 1915, Freud was evidently aware that he was working at the precarious edges of scientific and intellectual certainty: ���Physics furnishes an excellent illustration of the way in which even ���basic concepts��� that have been established in the form of definitions are constantly being altered in their content���. From the outset, in his copy of Pearson, Freud is clearly worried about the reception of his very original ideas. On p.3, he marks out a passage with a dash in the margin that describes the antagonism intellectual upheaval involves: the slowness in accepting new forms of thinking ���ought not to dishearten us, for one of the strongest factors of social stability is the inertness, nay, active hostility, with which human societies receive all new ideas���.

Psychoanalysis is at its most eloquent when describing the doubleness of intent innate to the human mind. No wonder Freud���s interest was piqued on Pearson's next page, where he underlines the final sentences of a paragraph that begins: ��� . . . we see the highest intellectual power accompanied by the strangest recrudescence of superstition . . . the extremes of religious faith and unequivocal free thought are found jostling each other. Nor do these opposing traits exist only in close social juxtaposition. The same individual mind, unconscious of its want of logical consistency, will often exhibit our age in microcosm���.

What is more exemplary of the unconscious than persistent ambivalence? Freud���s work often sketches the way we, despite living in a world of instrumental reason and reassuring knowledge, often have recourse to archaic and irrational forms of belief: the ���strange recrudescence��� in people Pearson describes. As the writer Adam Phillips put it in his recent biography, Freud "shows us how ingenious we are in not knowing ourselves���, or, indeed, how little notice we take of what we do know.

Critics of psychoanalysis often oppose its emphasis on individual pathology in lieu of wider social and political forces, but Freud���s underlining raises a rather more interesting proposition. Perhaps the psyche itself is riven from without by cultural and political antagonisms, and the symptoms that manifest ��� a persistent cough or a slip of the tongue ��� express ructions in both inner and outer worlds. Freud���s wartime annotations show how his thought oscillated between these overlapping worlds.

August 27, 2015

Charles Tomlinson at the crossroads

Charles Tomlinson, photographed by Norman McBeath

By ALAN JENKINS

Charles Tomlinson, who died last week, was born in 1927, published his ���first pamphlet of verse��� in 1951 and his first volume in 1955, and spent most of his life teaching English literature at Bristol University. That looks, on the face of it, like the career of an archetypal Movement poet, but Tomlinson���s work tells a rather different story. From that first volume, The Necklace, on, Tomlinson stood at a kind of crossroads, his collections embodying the tension between opposing tendencies in postwar Anglophone poetry: raw and cooked, ���art��� and ���life���, inner and outer, parochial and international ��� that can still be felt today . . . .

A glance at the title pages of his early books ��� ���Aesthetic���, ���Venice���, ���Nine Variations in a Chinese Winter Setting���, ���Flute Music���, ���The Art of Poetry���, ���At Delft (Johannes Vermeer)���, ���Farewell to Van Gogh��� ��� suggests the very poet Kingsley Amis had in mind when he said ���Nobody wants any more poems about philosophers or paintings or novelists or art galleries or foreign cities or other poems���. Tomlinson grasped that particular nettle in his poem ���More Foreign Cities��� (���Not forgetting Ko-jen, that / Musical city . . .���). And the preface he wrote for his Collected Poems in 1985 carries an implicit rejection of the claims Al Alvarez had made twenty-five years earlier for ���confessional��� or ���extremist��� poets such as Robert Lowell, John Berryman, Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes in his introduction to The New Poetry, and perhaps also of the claustrophobic personal anguish specialized in by Ian Hamilton and the poets in his influential magazine The Review . ���I realized when I wrote [���Poem���, one of his earliest pieces]���, Tomlinson says, ���that I was approaching the sort of thing I wanted to do, where space represented possibility and where self would have to embrace that possibility somewhat self-forgetfully, putting aside the more possessive and violent claims of personality. The embrace was, all the same, a passionate one, it seemed to me . . .���.

This self-denying ��� or liberating, depending on your point of view ��� ordinance was prefigured in the exchange between Alvarez and Donald Davie in the first number of The Review in 1962, and the distancing (or dissatisfaction, or distaste) it entails is still a matter of contention, for some. Davie, who had begun his critical career with Purity of Diction in English Verse (1952), a manifesto for the Movement in all but name, had tutored Tomlinson at Cambridge, and was one of his earliest critical champions (another was Hugh Kenner, still pre-eminent among explainers of Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot and other American Modernists). Davie���s focus on an Augustan ���purity��� and clarity in diction and syntax had, by 1955, when he published Articulate Energy, widened to include the musical aspects of French Symbolist poetry ��� De la musique avant toute chose. Tomlinson quoted this line of Verlaine���s in ���Antecedents���, one of the most interesting among his early poems (and poems of the 1950s), a ���Homage and a Valediction��� to the shades and the artistic assumptions of the late nineteenth century, from Wagner and Nietzsche to Laforgue and Mallarm��, and their diminished survivals in the twentieth.

Between appearing in New Lines (the anthology edited by the late Robert Conquest which announced the Movement in 1956) and The New Poetry (which attempted to kill it off), however, Davie had experienced a revelation, which went something like this: the condition to which poetry should properly aspire was not that of music, but sculpture; its proper raison d�����tre was an enhanced attention to ���the world bodied over against the eye���. The preferred antecedent was no longer Verlaine but Th��ophile Gautier, who described himself as ���un homme pour qui le monde visible existe���: a man for whom the visible world has an existence. Rather than expressing or recording an inner state, poetry would provide a rigorous exploration of whatever was ���out there���.

Pound had played a central part in Davie���s apostasy, as had ���Objectivist��� followers of William Carlos Williams such as Louis Zukofsky and George Oppen. Although the debt most clearly owed by Tomlinson���s own poems, early and late, is to Wallace Stevens and Marianne Moore, he found sustenance and a sympathetic hearing among these same representatives of a very different American tradition, to whom (like Davie) he later added Robert Creeley and Ed Dorn as valued exemplars. The possibilities of space, whether in Gloucestershire or Somerset, in Tuscany or New Mexico, the perceiving eye���s (as against the ���I������s) relation to it, and that relationship as recorded by other arts and artists, continued to preoccupy Tomlinson in a way that placed him outside the Anglo-American mainstream, whether that was embodied by Lowell or Larkin. He became a standing (or moving) reproach to the insularity of the Movement, and Larkin in particular. Although from 1958 he and his family lived at Brook Cottage, Ozleworth Bottom, Wotton-under-Edge ��� splendidly, almost caricaturally English address ��� from there he travelled widely, making long-lasting literary friendships, notably with Octavio Paz, and translating: from the Spanish of Antonio Machado and the Russian of Fyodor Tyutchev (with Henry Gifford), from C��sar Vallejo and Attilio Bertolucci. Out of this aspect of his work came an invaluable Oxford Book of Verse in English Translation, and Metamorphoses: Poetry and translation, an absorbing collection of essays.

Notwithstanding, he retained a deep affection for whatever was traditionally English, and local, in architecture, crafts, materials, properties of land and weather; and all these found their way into his poems at different times, albeit their personal importance to him is very indirectly conveyed. Indirectness aside, this aspect of his work makes him sound a Hardyesque kind of poet, but of Hardy in his poems there is barely a trace. His pared-down, free-verse evocations of place are arresting, but there are probably too many of them, and his more expansive, meditative poems can decline into stilted grandiloquence. Some of his best poems are casual-seeming, conversational, about the industrial Midlands where he was brought up, class and society. He enjoyed a high reputation among academic colleagues, but nothing he wrote earned him the wider critical acclaim and popular affection that were Larkin���s as if by right. (The same could be said of his lifelong friend Donald Davie, who blamed the ���lowered sights and diminished horizons��� that afflicted postwar poets and readers on the long shadow cast by Hardy ��� on Larkin especially ��� and devoted the brilliantly contentious Thomas Hardy and British Poetry to measuring it. But did either write anything with the direct appeal and ramifying force of ���The Whitsun Weddings��� or ���The Old Fools��� or ���Love Songs in Age���? ��� Not, of course, that ���direct appeal��� had much appeal for them.)

The last word should be Tomlinson���s, from an interview conducted by Willard Spiegelman for the Paris Review in 1998:

���A dangerously old-fashioned lifestyle? . . . For practically forty years I taught in a leading British university in our fifth largest city. We brought up a family of two girls and, like the rest of contemporary humanity, were busy getting them to school, to music lessons, to friends. We all went to the opera together and, by the time they began at the Royal Academy of Music, they had seen most of the classics. When we could afford it we went to Italy en famille and the world of Renaissance art and architecture awaited us. . . . Brenda and I have travelled all over the world���.We���re not in retreat from anything. . . . It���s not North Dakota, you know. Let me just say this: every day here is a quiet celebration of married love.���

August 25, 2015

On and off duty in Shanghai

By THEA LENARDUZZI

"I've already tried fish lips, thanks", I said, with relief, to my friend from the Shanghai Review of Books last week. "Canton greens and ginger instead?"

I was in town for the Shanghai International Literary Festival, a week-long series of talks, readings, panel discussions and presentations, now in its fifth year. The dim sum lunch pictured above (my paltry photography doesn't do it justice) followed a television interview and a trot around the hundreds of stalls filling the Shanghai Exhibition Centre, an immense neoclassical edifice built in 1955 and christened the Sino-Soviet Friendship Building. (The same gift was made to a number of cities around the world, although the only other still standing is in Poland.)

The previous night, I had taken part in a typically wide-ranging "forum" on the significance, past and present, personal and political, of ���The Orient��� ��� my contribution to which was deeply indebted to two recent TLS reviews, of Christopher Frayling's The Yellow Peril: Dr Fu Manchu and the rise of Chinaphobia and of Patrick Hanan's translation of the early-nineteenth-century novel Shenlou Zhi (Mirage). Fellow panellists included, among many others, the Chinese-American writer Gish Jen; the Welsh writer Francesca Rhydderch, whose debut novel, The Rice Paper Diaries, is based on her great aunt's experience as a POW in Hong Kong during the Second World War; and the Chinese writer Jin Yucheng, whose novel Evanescent had just won the prestigious Mao Dun prize. (Jin seemed to relish one speaker's suggestion that his book ��� which is written in a hybrid of Mandarin and Shanghainese dialect, with delicate ink illustrations by the author ��� is ���untranslatable���.)

On Thursday came the Poetry Gala, at which thirty-odd invitees were asked to select and read two poems. One of mine was Larkin's ���Aubade���, plucked from the TLS's archive, which succeeded in depressing almost everyone. Yeats's ���When You Are Old��� was a popular choice, read twice ��� once in English and then again in Korean. We heard contributions from Taiwan and Germany, France and Japan, as well as China, of course, interspersed with folk music from Moxizishi, who played a Kouqin, a southern Chinese mouth harp. The evening was filmed in its entirety to be broadcast on national television. It's almost impossible to conceive of such a show being made in the UK.

In between literary appointments and culinary (mis)adventures, I was free to roam and entertain myself. A favourite pastime during these off-duty hours was to wander through the city's French Concession, noting down restaurants and cafes with intriguing names or themes, from the does-exactly-what-it-says "Cheese + Chocolate" to the Wellingtonian "Beef and Liberty". There was also "Mr Bean Coffee", a memorabilia-packed coffee house nestled among the neck-cricking skyscrapers of the Pudong district, as well as "221B Baker Street" (cunningly located at 50 Ruijin Er Lu), which, at first glance, appeared to be Sherlock Holmes-themed, but on closer inspection, turned out to be a shrine to Benedict Cumberbatch.

To my colleague's compendium of felicitously mangled notices, I have this to add, which was slipped under my door one evening:

My week culminated in a discussion, with Professor Wen Jin, on ���Tradition and British Poetry���, in which we meandered from Anglo-Saxon verse to Geoffrey Hill and Eavan Boland, via Wordsworth and T. S. Eliot. Set in the intimate surroundings of the House of Literature in the Sinan Mansions, the event was well-attended (possibly something to do with an enormous billboard just down the road) and the audience was welcoming and engaged ��� even when I chattered away for a full ten minutes before realizing the need to allow an interpreter to fill everyone in. At the end there were questions on, among other things, the overlaps between nature poetry and realism, whether folk songs could be classed as poetry, and whether Simon Armitage had plans to publish in China. There was a cautious query, too, about the impact of censorship on poetry during the First World War.

And then it was time for yet another meal ��� the cutesy term ���baby lobsters��� making me feel only slightly guilty for eating an entire generation's worth.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers