Freud's books

By BENJAMIN POORE

Earlier this year I became involved in organizing a new exhibition: The Festival of the Unconscious, at the Freud Museum in Hampstead, which runs until October 4. I was to mine Sigmund Freud���s library to see who and what he was reading as he composed key papers, in particular his ���metapsychological��� works ��� ���The Unconscious��� being the most famous of them ��� which collectively celebrate their 100th anniversary this year.

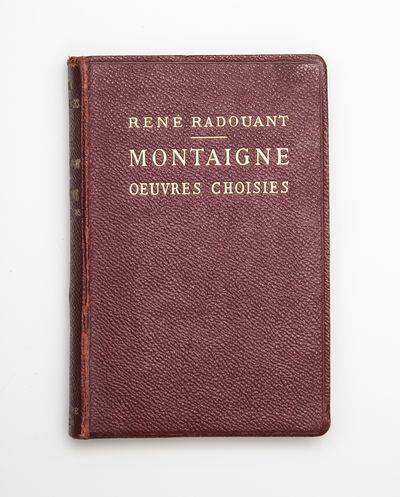

Psychoanalysis is all about the details, and so looking for Freud���s notes and annotations seemed an appropriate way to start. One of the first books I came across was his copy of Montaigne���s Selected Works, edited by Ren�� Radouant and published in French in 1914. Freud���s underlinings suggest that he was reading the great essayist in the opening years of the First World War, so powerfully do the annotations resonate with the anxieties and fears that punctuate Freud���s writing in this period.

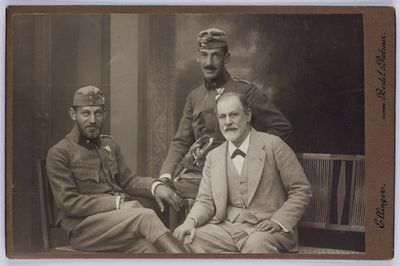

Freud with his sons Ernst and Martin in Salzburg, 1916

Freud was hardly removed from the furious political and social upheavals of the war ��� his own sons, with whom he is pictured above, were at the Front ��� so it might seem curious that his writing is both abstract and speculative. Yet death and hostility loomed large for Freud in these years. Think of the bucolic On Transience, which featured a disguised and miserable Rainer Maria Rilke; the gloomy Mourning and Melancholia, eventually published in 1917; and Thoughts for the Time on War and Death, published in late 1915, as Freud���s initial excitement about the war soured into the prevailing cultural pessimism of his later work.

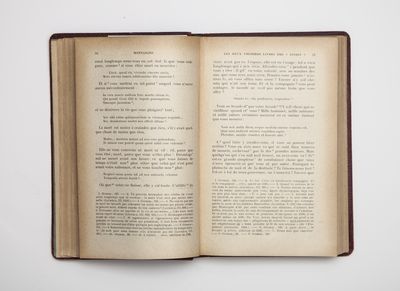

Montaigne's essay ���That to Philosophise is to Learn to Die��� is especially well-thumbed. In Radouant���s introductory rubric, underlinings and jottings point us towards the resolute stance on death taken in Thoughts for the Time, with Freud remarking: ���Montaigne refused to admit to himself that virtue could be separable from suffering���. Freud's insistence that we must take death in our stride is echoed elsewhere in his reading, too. In Montaigne���s essay itself he underscores the remark that ���the value of life is not to be found in its length, but rather its employment���.

Such marginalia offers the first indications of the ethical and moral preoccupations that war would increasingly encourage in his work. To ���bear life���, he went on to write in Thoughts for the Time, we must accept its brevity and fragility. We should, it follows, take ���the truth into account a little more���: this would make life ���more bearable again���.

Freud's copy of Montaigne forms a key section of the exhibition titled ���Reading the Unconscious���, where it joins other books on display, including collections of Rilke���s poems belonging to his daughter, Anna.

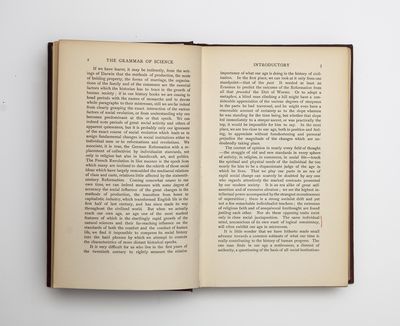

The exhibition is also traces the links between Freud���s ideas about the unconscious and contemporary scientific writing. This is particularly visible in a 1911 edition of The Grammar of Science, by the English statistician Karl Pearson. The book is annotated thoroughly, the reader's compact scribbling betraying anxieties about the ambitious nature of his own developing theories. (Pearson, like Freud, was involved in the radical political and social movements of the early 1900s, most alarmingly in his enthusiasm for eugenics.)

In Drives and Their Fates, also from 1915, Freud was evidently aware that he was working at the precarious edges of scientific and intellectual certainty: ���Physics furnishes an excellent illustration of the way in which even ���basic concepts��� that have been established in the form of definitions are constantly being altered in their content���. From the outset, in his copy of Pearson, Freud is clearly worried about the reception of his very original ideas. On p.3, he marks out a passage with a dash in the margin that describes the antagonism intellectual upheaval involves: the slowness in accepting new forms of thinking ���ought not to dishearten us, for one of the strongest factors of social stability is the inertness, nay, active hostility, with which human societies receive all new ideas���.

Psychoanalysis is at its most eloquent when describing the doubleness of intent innate to the human mind. No wonder Freud���s interest was piqued on Pearson's next page, where he underlines the final sentences of a paragraph that begins: ��� . . . we see the highest intellectual power accompanied by the strangest recrudescence of superstition . . . the extremes of religious faith and unequivocal free thought are found jostling each other. Nor do these opposing traits exist only in close social juxtaposition. The same individual mind, unconscious of its want of logical consistency, will often exhibit our age in microcosm���.

What is more exemplary of the unconscious than persistent ambivalence? Freud���s work often sketches the way we, despite living in a world of instrumental reason and reassuring knowledge, often have recourse to archaic and irrational forms of belief: the ���strange recrudescence��� in people Pearson describes. As the writer Adam Phillips put it in his recent biography, Freud "shows us how ingenious we are in not knowing ourselves���, or, indeed, how little notice we take of what we do know.

Critics of psychoanalysis often oppose its emphasis on individual pathology in lieu of wider social and political forces, but Freud���s underlining raises a rather more interesting proposition. Perhaps the psyche itself is riven from without by cultural and political antagonisms, and the symptoms that manifest ��� a persistent cough or a slip of the tongue ��� express ructions in both inner and outer worlds. Freud���s wartime annotations show how his thought oscillated between these overlapping worlds.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers