Peter Stothard's Blog, page 24

June 16, 2015

Wandering through Waterloo

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

The battlefield at Waterloo, 18 kilometres south of Brussels, is flanked by the N5 motorway heading south from the Belgian capital to Charleroi. It���s also about 4 kilometres south of Waterloo itself (no more than a village in 1815, most of whose 1,800 inhabitants fled in the hours leading up to the epochal event). June 18 was a Sunday (no rest for the military then) and those attending church services in Brussels were, it is reckoned not much after 11 am, made anxious by the sound of cannon fire.

Of course you don���t have to be a military historian to be fascinated by Waterloo. Or a historian tout court. Granted it was the last major military engagement of the European pre-industrial age. But Waterloo seems to transcend history. It is, in the French historian���s term, one of the ���great sites of memory��� of modern Europe.

And that site was to contain, on June 18, a mere two days after ferocious engagements at Ligny and Quatre-Bras, upwards of 200,000 soldiers, 60,000 horses and 537 artillery pieces, in undulating fields of rye, lined with ridges, punctuated by woods and copses, and dotted with the odd farm building: Hougoumont, La Haye Sainte.

A couple of hundred metres to the left of the motorway is the brand new underground Waterloo Memorial (it opened at the end of May), a stunning interactive museum full of lifelike exhibits, screen reproductions of paintings from the era, and a great deal more. The visit culminates in an extremely effective fifteen-minute film of the battle, seen through 3-D glasses.

Exiting into the light, the visitor is drawn to the handsome nearby rotunda, housing the vast panorama, 110 metres in circumference, of the battle by the Parisian artist Louis-Jules Dumoulin, which he started in 1912. It���s showing its age a little, but has an undeniable grandeur. From there, it���s up the 226 steps to the Butte du Lion, or Lion���s Mound, raised to mark the spot where the Prince William of Orange, later King William II of the Netherlands, was wounded. (���They have ruined my battlefield���, Wellington complained.) The platform at the foot of the bronze lion offers a panoramic view of the site; it must be said that ��� as expected and perhaps appropriately ��� there is not a great deal to see: undulating fields; still-standing Hougoumont, where Napoleon launched a furious assault on British troops. But it���s still an evocative sight.

Wellington stayed in Waterloo on the nights of June 17 and 18, in a pleasant inn that now houses the Waterloo Museum. According to two attendants I spoke to, very few French people come to the museum. It can���t be too painful still, after 200 years? Or is the memory of Napoleon tinged with embarrassment at the carnage he wrought across Europe? Among the exhibits are some brutal-looking surgical instruments and the artificial leg worn by the British commander Lord Uxbridge (his real leg is buried in the garden at the back, under a memorial plaque): Uxbridge is said to have exclaimed to Wellington, ���By God, sir, I���ve lost my leg!���, to which the Duke replied: ���By God, sir, so you have!���

���Nothing, except a battle lost, can be half so melancholy as a battle won���, said Wellington.

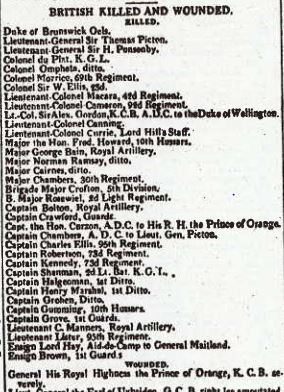

The Times of June 22 (below) published the Official Bulletin: ���The Duke of Wellington���s Dispatch, dated Waterloo, the 19th of June, states, that on the preceding day Buonaparte attacked, with his whole force, the British line, supported by a corps of Prussians: which attack, after a long and sanguinary conflict, terminated in the complete Overthrow of the Enemy���s Army, with the loss of ONE HUNDRED and FIFTY PIECES of CANNON and TWO EAGLES. During the night, the Prussians under Marshal BLUCHER, who joined in the pursuit of the enemy, captured SIXTY GUNS, and a large part of BUONAPARTE���s BAGGAGE. The Allied Armies continued to pursue the enemy. Two French Generals were taken.��� Wellington later admitted that it had been the ���nearest run thing you ever saw in your life���.

The Waterloo site is off-limits from the 17th to the 21st, as a re-enactment of the battle will be taking place. That should be quite a spectacle.

June 15, 2015

���Ferrante Fever��� and other symptoms

Paola Capriolo (left) and Viola Di Grado (right); �� Leonardo Cendamo/Writer Pictures

By THEA LENARDUZZI

If you don���t count the one-woman sensation that is Elena Ferrante ��� whose agile prose has found her not a few (well-deserved) admirers in our recent Summer Books feature ��� Italian literature has been having a rather tough time of it in recent years (recent decades, some would say). When I left Italy for England in 2004, Ugo Riccarelli���s Il dolore perfetto had just won the Strega prize, Paola Mastrocola had won the Campiello with Una barca nel bosco, and Franco Cordero had taken the Bagutta for Le strane regole del sig. B. A cursory search suggests that I was the only one of us to make it to England. Statistics haven't improved much in the past ten years. Of last year's winners ��� Francesco Piccolo, Giorgio Fontana, Maurizio Cucchi and Valerio Magrelli (joint winners of the Bagutta) ��� only Magrelli, and to a lesser extent, Cucchi, are likely to ring any bells among English readers (Magrelli's poetry in particular, translated by Jamie McKendrick, has been praised highly in the TLS).

Italy���s performance on the international literary scene seems generally weak, compared with, say, that of France or Spain. Why? Well ��� it's complicated. But perhaps we can take heart from what the publishing industry calls ���Ferrante Fever���. Is this an opportunity for writers of the same nationality to win an anglophone readership?

I know which recent novels I'd recommend. If Viola Di Grado���s debut novel 70% Acrylic 30% Wool announced ���the arrival of a considerable talent ��� (as our reviewer put it last year), her second novel, Hollow Heart, published this month by Ferrante's publisher, Europa Editions, confirms that the author has in fact thrown open her bags and set about moving in permanently. The novel ��� which will be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS ��� begins with the protagonist���s suicide and charts the decomposition of her body, as mind and matter struggle to go their separate ways. Themes from the first novel ��� the life/death binary, the female form (physical as well as literary) ��� are reprised and developed here in an extraordinary feat of linguistic gymnastics expertly captured in Anthony Shugaar���s translation.

Similar themes have long occupied the writing of Paola Capriolo, a novelist who was last reviewed in these pages in the days when Italy still had its own currency. Writing on La Spettatrice and Un Uomo di carattere ��� at, if you���ll forgive a little nostalgia, 26,000 Lira each ��� our reviewer found in the Milanese's fabulist prose ���the unsettling pleasures of the perverse���; her forte, he concluded was ���the exquisite philosophical game played with corrosive scepticism���. Which sounds like just the stuff of good novels, doesn���t it? Her most recent offering in Italian is the typically elegant Mi ricordo. It tells the tale of two women, from different times, whose lives are mysteriously bound together in the walls of a once-grand mitteleuropean villa (a favourite trope of Capriolo���s). We���ll be running a review of this one in the coming months, too.

Among the rest, I'd look out for The Other Language by Francesca Marciano (who actually writes in English), which appeared earlier this year, as did a dark triptych called Cocaine, featuring stories by Massimo Carlotto, Gianrico Carofiglio and Giancarlo De Cataldo; while Marco Missiroli���s fourth novel Il Senso del elefante and Alessandro Spina���s I confini dell���ombra are both due to appear in English later this summer. But perhaps I���d best keep those for a future post. Are you meant to feed or starve a Ferrante fever?

June 12, 2015

Melancholy John Ford

By MICHAEL CAINES

Brother, dear brother, know what I have been,

And know that now there's but a dining-time

'Twixt us and our confusion . . .

For William Hazlitt, there was little to admire in the plays of John Ford. ���I do not find much other power in the author . . . than that of playing with edged tools, and knowing the use of poisoned weapons���, he announced in the course of a lecture on English dramatists. ���Except the last scene of the Broken Heart . . . they are merely exercises of style and effusions of wire-drawn sentiment.���

Even the great critics nod, I suppose . . . .

Hazlitt was challenging the high opinion of Ford held by Charles Lamb, for whom he was to be placed in the ���first order of poets��� as ���the man after Shakespeare���. (The first phrase appears in Specimens of English Dramatic Poets, the second in a letter to William Wordsworth.) I wonder: would those who saw the recent productions of Love���s Sacrifice, The Broken Heart and ���Tis Pity She���s a Whore agree with Hazlitt or with Lamb?

It is pretty clear where Brian Vickers, as editor-in-chief of the Collected Works of John Ford, stands on the question of Ford���s artistry. Professor Vickers gave the Sam Wanamaker Fellowship lecture last night, after being introduced as the author of (among many other things) some ���searingly astute��� criticism; TLS readers may well know what Patrick Spottiswoode meant by that remark.

Last night, however, Vickers���s theme was essentially a celebratory one: his subject was ���John Ford and feminine virtue���, and the argument was supported entertainingly by acted-out excerpts from several of the plays. (The professionals did most of the acting, but the professor gamely took on the necessary supporting roles: courtier, father figure, low-life friend.)

Born in 1586, Ford had taken a familiar course towards a play-writing career, via the University of Oxford and the Middle Temple; non-dramatic works and dramatic collaborations seem to have given way to the independently written works of the Caroline era, including The Lover���s Melancholy, the recent revivals mentioned above and that remarkable history play Perkin Warbeck. Satisfyingly obscure in life ��� the date of his death is unknown ��� he was nonetheless a major writer of the 1630s, and the inspiration for a later witticism that seems to sum up the plays, if not the man:

Deep in a dump alone John Ford was gat,

With folded arms and melancholy hat . . . .

It was only in Hazlitt���s lifetime that a pioneering but unsatisfactory attempt was made to edit those plays for public consumption; fortunately, Henry Weber���s edition of 1811 did at least prompt others to improve on it. By the late 1950s, a TLS reviewer could note that Ford had become the subject of a ���quite respectable��� shelf of critical works ��� yet there had been no attempt to collect Ford���s work for a modern readership since Alexander Dyce���s edition of 1869 (reprinted in 1895).

(Doesn���t it seem odd that so much scholarly energy has gone into endlessly re-editing Shakespeare ��� the Forth Bridge of English literary editorship ��� when a decent old-spelling edition of Ford is only now in the works? But that���s easy to say in retrospect, I suppose. Cf. Ford���s contemporaries Philip Massinger, who had to wait until the 1970s, the current James Shirley project and Richard Brome, now available online and well worth a look.)

The argument about Ford, meanwhile, as G. F. Sensabaugh saw it, had swung between predictable poles of regarding him as a ���high priest of decadence��� or a ���prophet of a modern world���. When it came to Ford, morality and art got themselves in the usual tangle. The smitten Swinburne could praise The Witch of Edmonton, one of the collaborations, as a ���play of rare beauty and importance both on poetical and social grounds���, but condemn Love���s Sacrifice as ���intolerable���: ���utterly indecent, unseemly and unfit for handling���. John Buchan followed Havelock Ellis: Ford anticipated Stendhal and Flaubert as an ���exponent of the naked human soul��� and ���the most modern of the Elizabethans���. Muriel Bradbrook thought him an ���imitator��� of ���limited range���, guilty of ���gawkiness���. Allardyce Nicoll wrote of ���Tis Pity:

���The novelties in the torments . . . have no dramatic purpose; they are there merely to arouse curiosity and thrill the hearts of a jaded public.���

T. S. Eliot, writing in this paper, deemed his comic scenes to be ���quite atrocious��� and likened Ford���s sensationalist, edged-tools side to that of Beaumont and Fletcher, James Shirley and the later Thomas Otway ��� but he also acknowledged Perkin Warbeck to be ���almost flawless���, and was entranced by the ���slow solemn rhythm��� of Ford���s verse:

Minutes are numbered by the fall of sands,

As by an hourglass; the span of time

Doth waste us to our graves, and we look on it:

An age of pleasure, revelled out, comes home

At last, and ends in sorrow . . .

Listening to the scenes from Ford���s plays last night, I think I caught that distinctive rhythm from time to time.

In contrast to those critics who have seen Ford as a better poet than dramatist, or thought him somehow modern rather than of his time (his debt to Robert Burton���s Anatomy of Melancholy can hardly be ignored), but perhaps in keeping with Mark Stavig���s John Ford and the Traditional Moral Order (1968), Vickers celebrated the ���virtues��� of Ford���s female protagonists with the deeply chauvinistic prejudices of the age. In the face of medical, Christian and ethical commonplaces, his Ford is ��� after Shakespeare, indeed ��� a dramatist who suggested that it was men rather than women who suffered from dangerous chemical and psychological imbalances. But there will be a further opportunity to ���test��� that view when the Globe���s ���Ford Experiment��� concludes in the autumn, with the Edward���s Boys production of The Lady���s Trial ��� I hope to be among the jaded public for that, too.

June 9, 2015

Bj��rnstjerne Bj��rnson at home

By CATHARINE MORRIS

The Norwegian writer Bj��rnstjerne Bj��rnson was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1903, "as a tribute to his noble, magnificent and versatile poetry, which has always been distinguished by both the freshness of its inspiration and the rare purity of its spirit". He wrote not only verse but also plays and novels, as well as countless articles; and it was with his pen, our tour guide Kari Elisabet told us at Bj��rnson���s farmhouse ��� now a museum ��� in Gausdal a fortnight ago, that he took part in the great political issues of the day. We were staying in Lillehammer for Norwegian Festival of Literature (more on that to come in a future post); and some of us were curious to hear more about the man Margaret Atwood had honoured in delivering the Bj��rnson Lecture that morning (her title: ���What is a Book?���).

Born in the ��sterdalen district of Norway in 1832, Bj��rnson was still an undergraduate when he started publishing stories and criticism in various newspapers. In 1857 he joined the Norwegian Theatre in Bergen as stage director, and published a novel, Synn��ve Solbakken (striking partly because of its choice of characters: they were farmers), which brought him almost instant fame. He would later say of Synn��ve Solbakken: ���I did not write merely to make a book. What I wrote was a plea on behalf of those who worked the land . . . . We had come to see that the language of the sagas lived on in them, and that their life lay close to the sagas. The life of our nation was to be built on our history, and now these were the people who were to provide the foundation���.

Norway had been granted its own constitution in 1814, but it was that year joined in a union with Sweden, and Danish remained the standard written language. As Bj��rnson���s comment on his novel makes clear, literature, for him, was partly a means of forging a new national identity. A TLS review by James McFarlane published in 1958 refers to the ���crop rotation��� working method Bj��rnson employed in the first part of his career, ���the Peasant Tales on the one hand, with their contemporary themes and their happy endings; and on the other the dramas, saga-inspired and tragic. In both, the design deliberately stressed the links that bound the new Norway to the old���. Bj��rnson created, he said, ���an image of Norwegian life that was like enough to be recognizable but idealized enough to constitute an incentive���.

Bj��rnson���s work evolved, of course; he moved, for example, from historical plays to ones that examined contemporary society in quite realistic terms, among them Redakt��ren (1875; The Editor); En Fallit (1875; A Bankruptcy); and En Handske (1883; A Gauntlet), which drew attention to moral double standards in marriage unions, and was said to have resulted in the calling off of hundreds of engagements. For McFarlane, Bj��rnson���s play Over ��vne (1883; Beyond our Powers) stood out for its non-conformity as well as its consummate artistry: ���Elsewhere it is generally only too clear whose side Bj��rnson is on, and where one���s sympathies are meant to lie; but here is a play impious in design yet sustained by a great piety, where sceptic and believer appear equally vulnerable, where fanaticism is not without sublimity, where reasonableness seems faintly comic, and where irony never loses its dignity . . . . Beyond our Powers reflects Bj��rnson���s newly won conviction that decency and morality count for more than any officially Christian faith���.

Bj��rnson moved to the farm, Aulestad ��� with his wife Karoline (n��e Reimers) and their children ��� in 1875, coaxed back from an Italian sojourn by the suggestion that he���d be surrounded by friends there, and by news that a school was opening near by whose ethos was that of N. F. S. Grundtvig, whom he deeply revered. Karoline (captured in Bj��rnson���s correspondence as a young woman light of foot as she gaily danced, but who became ever more stately as she took on more and more responsibility) set about decorating the house in an invitingly opulent and eclectic style. Bj��rnson was a keen early adopter of new inventions, so there is a fridge, of sorts, and a shining hot water urn. As we moved from room to room, we were experiencing the house almost exactly as Bj��rnson would have: all the furniture is original. A focal point was a small round table at which Bj��rnson would talk for hours, with his family and a steady stream of visitors . . . .

���Active, beneficent, eccentric���, wrote Edmund Gosse of Bj��rnson ensconced at Aulestad; ��� ��� a sort of Golden Farmer in his laughing valley among the dark pine-plumaged mountains���. Having once met Bj��rnson himself, Gosse was able to describe him entering ���affably into a loud torrent of talk, lolling back, shaking his great head, suddenly bringing himself up into a sitting posture to shout out, with a palm pressed on either knee, some question or statement . . .���. (For a lively summary of Bj��rnson���s works, see Gosse���s introduction to his novel The Heritage of the Kurts, which you can read online here.) Kari Elisabet pointed out that in this respect ��� his conviviality ��� Bj��rnson was the polar opposite of Henrik Ibsen, who was quiet, restrained, introspective, aloof. These two pre-eminent literary figures knew each other for most of their lives but fell out intermittently ��� perhaps the biggest rift being caused by Ibsen���s play De unges Forbund (1869; The League of Youth): the protagonist, Stensgaard, was believed by many to have been modelled on Bj��rnson, and the play therefore to constitute an attack on him. Life can���t have been entirely straightforward for Ibsen���s son Sigurd (Prime Minister of Norway in Stockholm, 1903���05) and Bj��rnson���s daughter Bergliot (a mezzo soprano), who married in 1892.

Bj��rnson caused rows wherever he went; Kari Elisabet made that very clear. When I asked her for more detail, she said that a lot of trouble was caused by Bj��rnson���s view that there should be Norwegian plays in the Norwegian language; and that his strong social conscience led him, for example, to sue the local doctor when a woman who worked on the farm died after being sent home without treatment: it would not have happened, he believed, if she had been a rich woman.

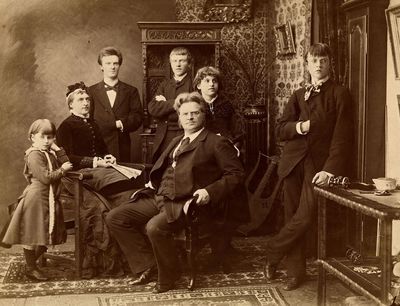

Above: Bj��rnstjerne Bj��rnson in 1909;

Bj��rnson and his family, 1882;

Bj��rnson and his wife Karoline at Aulestad

June 4, 2015

BHL and the custard pies

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

I don���t know if the French intellectual Bernard-Henri L��vy (above) knows the Led Zeppelin song ���Custard Pie���, but if he does it���s unlikely to be on his playlist at the moment. The Figaro reports that last Saturday evening BHL (as he is commonly known) was custard-pied in Namur in Belgium as he was on the way to a public debate (the topic is not disclosed), in spite of the fact that he was accompanied by two bodyguards.

His assailant, as on previous occasions ��� this is the ninth time that poor BHL has been pied by him ��� was the Belgian writer and anarchist No��l Godin (below), whose previous targets, chosen, according to him, for sense-of-humour deficiency, include the dancer and choreographer Maurice B��jart, the novelist Marguerite Duras, Nicolas Sarkozy, and Bill Gates (Brussels, 1998).

Is Godin, whose books include Cr��me et chat��ment: M��moires d���un entarteur (Cream and punishment: Memoirs of a pie thrower), in a fine tradition of Belgian farceurs or is he a public nuisance? In the case of BHL, maybe it was funny the first couple of times but surely enough is enough. BHL says he���s fed up with him, which is understandable. Aside from the public humiliation of being covered in cr��me Chantilly (however pleasant that may be), there���s the inevitable need for a wardrobe change. One of the first assaults, which took place in 1985, is on film (BHL doesn���t come well out of it, threatening Godin with violence). Another very public one took place at Nice airport, when L��vy was in the company of his glamorous wife.

BHL plays an important role in French public life, taking stands that are not always popular and even influencing policy: he pushed President Sarkozy into military action in Libya in 2011. He���s an outspoken intellectual who divides opinion. It���s a little bit as though Will Self had to worry about being pied every time he stepped out into public. Rather restricting.

But BHL is also considered something of a narcissist in France and neighbouring Belgium. He used to wear white shirts with billowing sleeves unbuttoned practically to the navel. He arguably takes himself a little too seriously. Maybe if he lightened up, his tormentor would leave him alone. Or turn to another target. How about Marine Le Pen?

June 2, 2015

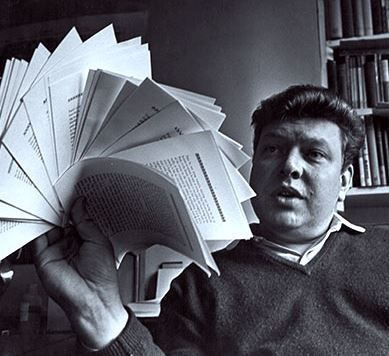

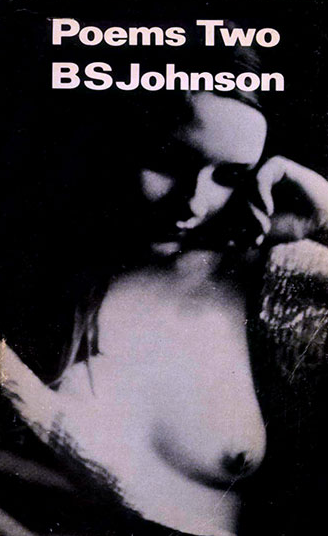

B. S. Johnson the poet

-

-

By CATHARINE MORRIS

B. S. Johnson is well known for his experimental novels ��� Albert Angelo (1964), Trawl (1966), House Mother Normal (1971), Christie Malry���s Own Double Entry (1973). Much less well known are his two volumes of poetry (which are out of print) ��� Poems (1964) and Poems Two (1972). Chris McCabe of the Saison Poetry Library did something to address that neglect last month, hosting an evening of readings and discussion of Johnson���s poetry. In welcoming the speakers ��� Alan Brownjohn, John Lucas and Julia Jordan ��� McCabe described Johnson as ���a special figure in poetry���. A cult figure, in fact: ���I wouldn���t say he���s a popular poet . . . but he is one of those poets whose books get stolen more than others���.

Poetry was Johnson���s first love, Brownjohn told us, and perhaps even continued to be his principal love; it was something he did ���with great technical attention and great technical care���. And like his novels, his poetry has ���a quality of candour and honesty which he doesn���t flinch from, even when he might have feared offending the reader . . . or embarrassing the reader, because his frankness . . . endears him to the reader, and draws you in���. In ���Good News for Her Mother!���, for example (there���s a subtitle: ���Probably the last poem I shall write about her daughter���) ���

In the last year ending with eight (cunningly

making it timeless) ten years ago, that is,

I was in this pub with this girl, or that girl,

whichever, the one girl, anyway, one one:

and it was very clear, then, at that time, here,

that she didn't reckon I'd ever make it . . . .

��� Johnson is ���trying to forget���, said Brownjohn, ���trying to have done with a particular person . . . we���ve got the fool Johnson, we���ve got the resentment, we got the rueful humour, we���ve got the range of disappointment in the Johnson genius, and the range of idiosyncrasy with the language that his poetry contained��� (Brownjohn said he could think of no other poet who played with the words ���this���, ���that��� etc in the way Johnson does here). Brownjohn also read us ���Love-all���, another funny, regretful poem (���The decorously informative church / Guide to Sex suggested that any urge / could well be controlled by playing tennis���, it begins), and ���The Short Fear���, which Johnson wrote not long before he took his own life in 1973, and which communicates doubt ���very very tersely, very very plainly���.

For Julia Jordan, Johnson was a writer obsessed with the pursuit of truth; but in his poetry he seems aware that ���this notion of truth is always sort of a lie��� ��� that complete honesty is difficult to achieve. She suggested that the bathetic ���anti-epiphanies��� at the end of many of his poems were part of his ���memorialization of the failure���; and noted that ���A Suggested End to the Celebrated Long Run��� ���

. . . unbroken chains of causality reach

back in time and space indefinitely.

Where start then?

Here

��� was evidence of his preoccupation with the arbitrary, the random, and his ���hatred of this idea of endings, of closure��� (a hatred also expressed in his shuffle-able novel The Unfortunates (1969) ��� though, as she pointed out, that does in fact have a beginning and an end: ���the publisher . . . won that battle���).

Jordan observed that Johnson���s use of syllabics amounted to a refusal to indulge in the more high-flown aspects of poetry. John Lucas was not convinced that they helped Johnson: ���I think they often create a kind of hippety-hoppety rhythm which you have to get round in a reading which actually destroys them���. He later went further (���I don���t think Bryan was naturally a poet ��� I���m sorry to say this���), citing Thom Gunn���s poem ���Considering the Snail��� as an example of how it should be done: ���it uses seven-syllable lines. Now I think that���s crucial, because if you���re writing in syllabics you need to get as far away as you possibly can from the iambic, and I think the problem with Johnson using syllabics is that he actually does use eight- and ten-syllable lines. So the temptation is to hear those lines as iambic lines, and when they aren���t iambic, it feels most peculiar���.

For Jordan, Johnson was ���absolutely a poet���; ���I actually think the poetry is more successful in what it���s doing, often [than the novels]���. Jordan is troubled by the misogyny she sees in some of them, ���but when they���re good���, she said, ���I think they���re up there with absolutely everything that���s going on in the 1960s���.

The speakers touched on Johnson���s relationship to the poetic avant-garde (Brownjohn pointed out that Johnson didn���t write sound poetry or do anything with shapes and forms on the page, as Bob Cobbing was doing), and his interest in architecture (Jordan saw a connection between his mathematically precise or architectural language and his interest in ���the unregulated big scary sublime���). There was also a mention of the dialogue in Johnson���s film You���re Human Like the Rest of Them (1967), which is in iambic pentameter; and a discussion of Johnson the person.

He was a big man, said Brownjohn: ���not quite Falstaffian; he didn���t have the outgoing, outrageous robustness . . . . There was always something really rather sad about his fatness, his roundness, his jolliness ��� something in the eyes���.

Brownjohn fondly and gratefully recalled the time, ���fifty-seven years and seven months ago���, when Johnson gave up a fortnight of his writing time to drive him ���several hundred miles and knock on twice as many doors��� before the 1964 general election (in which Brownjohn was standing as a candidate for Richmond and Barnes). This wasn���t out of character. Brownjohn remarked, in relation to the section titles in Poems Two ��� ���Exorcising���, ���Loving���, ���Observing���, ���Unthinking��� and ���Rotting��� ��� that it was ���a pity it stopped there, because B. S. Johnson���s was also a life of doing, committing, giving and, friends would have added, indulging and laughing���.

Lucas confirmed that impression, saying of Johnson���s stint as poetry editor of the Transatlantic Review that ���he behaved with great generosity as well as I think scrupulousness towards a lot of younger persons including myself who were sending him poems���. Lucas met Johnson in 1966, when, as a young lecturer at Nottingham University, he went to hear him give a talk there. On this occasion another aspect of Johnson���s personality was in evidence: ���Johnson spent more or less the entire hour attacking the world of academe, and pointing out that people who were in the world of academe could be expected to understand nothing about literature at all���. Afterwards Lucas approached Johnson holding a copy of Poems, ���which sufficiently warmed him to me for us to go off to the pub��� (the pub ��� according to Lucas ���a kind of Wild West saloon��� in which ���prostitutes, footballers and rogue millionaires rubbed shoulders with each other and upstairs there was an air . . . of forlorn decorum��� ��� was the one referred to in Johnson���s poem ���In Yates���s���).

When Lucas asked Johnson which poets he had been influenced by, he replied that he admired not only David Wright (another poet of bare statement, Lucas pointed out) but also Robert Graves ��� The White Goddess in particular ��� and the Cornish poet Jack Clemo. Lucas was astonished by this, ���partly because Clemo was so obscure, but also because his brand of home-made rhetorical grandeur was at the very opposite of what I expected Johnson to approve of���.

Brownjohn was particularly keen to explore this question of Johnson���s influences: as far as he could remember, Johnson rarely talked about poetry; he therefore finds himself looking for clues to Johnson���s reading in the poems themselves. ���You���re reading something in Bryan Johnson���s poetry and you . . . think that sort of echoes something somewhere . . . in the beginning of the ���Barents Sea��� poem, suddenly you realize that this comes out of a famous medieval love lyric . . . . It reminds you of . . . ���Quia Amore Langueo���. That, if you like, is someone who���s done an English degree and has looked into medieval lyrics. Or they have been given to him and he has been impressed by them, and he hasn���t forgotten them."

See Jonathan Coe���s biography Like a Fiery Elephant (2004) for more evidence of Johnson���s many facets . . . .

May 30, 2015

Edward Burra in Hastings

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

The Conservative MP for Hastings and Rye, Amber Rudd, described Hastings in 2013 as ���a bit depressing���. She may have a point, but that���s perhaps not the sort of comment that constituents would expect from their parliamentary representative. It turns out it did her little harm as she was re-elected earlier this month, with an increased majority. Nor did her as yet unfulfilled pledge, also made in 2013, to have the burnt-out pier ���rebuilt just in time for the election��� damage her electorally, it would seem. Incidentally, what���s with arsonists��� apparent obsession with seaside peers? Their handiwork can be seen up and down the British coast.

I wonder whether Amber Rudd has visited the Jerwood Gallery, which has graced Hastings���s seafront since it opened in 2012 as a ���permanent home in the public domain for the Jerwood Collection of twentieth and twenty-first-century British art���. According to Alan Grieve, Chairman of the Jerwood Charitable Foundation, ���the Collection has been created to underline the strength of Jerwood in supporting the visual arts, enriching a cultural heritage and stimulating regeneration in Hastings���. Blending in nicely with the black-painted wooden fishing huts and alongside the Fishermen���s Museum, the airy gallery is a gem, smaller than the modernist De La Warr Pavilion just up the coast in Bexhill-on-Sea, but scoring highly in quality. It includes works by Walter Sickert, David Bomberg, Christopher Wood, a surprisingly fine L. S. Lowry, Keith Vaughan (five works), John Minton, Julian Trevelyan, Maggi Hambling, among others.

The three current exhibitions feature a room of work by the Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi (until May 31), two rooms of works from the Fleming Collection which, according to the Jerwood, is ���widely regarded as the finest collection of Scottish art in private hands��� (there are several paintings by John Bellany). That runs until July 12.

The rather more local Edward Burra (1905���76) has two rooms dedicated to him upstairs (until June 7). Burra, who lived most of his life in and around Rye, dismissed the town as a ���ducky little Tinkerbell towne��� and ���like an itsy bitsy morgue quayte DEAD���. He was afflicted with arthritis from an early age (deforming his painting hand), but he still managed to travel widely, to Paris in the 20s, New York in the 30s; his depictions of the Harlem scene are particularly striking. Then there was Spain at the time of the Civil War, the horror of which he captured in his inimitable, visionary way. He spent the war mostly in Rye, witnessing the Battle of Britain at first hand.

The two rooms in the small exhibition (on a wall outside the rooms is John Banting's piercing 1930s portrait of Burra) mostly focus on his Sussex-based work, the most striking of which, in my view, is the pencil-and-watercolour ���Landscape near Rye��� (1943���5, below). Note the ominous dark clouds in the distance, the whole composition seems strange, with the dishevelled wigwam and the sheep's skull nestled between the arms of a plough in the foreground.

Andrew Graham-Dixon began his brilliant hour-long BBC documentary (broadcast to coincide with a Burra exhibition at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester in 2011) with the words ���This is a film about the most intriguing twentieth-century artist you may never have heard of". If that is the case, can I urge you to discover him?

May 29, 2015

Byron in prose

By MICHAEL CAINES

"He is like a solitary peak, all access to which is cut off not more by elevation than distance", William Hazlitt wrote of Lord Byron. "He is seated on a lofty eminence, 'cloud-capt', or reflecting the last rays of setting suns; and in his poetical moods, reminds us of the fabled Titans . . . . He scorns all things, even himself. Nature must come to him to sit for her picture ��� he does not go to her. . . ."

Hazlitt's sublime Byron appears in The Spirit of the Age in the course of a comparison with Sir Walter Scott, the contemporary poet for whom Byron himself expressed the most considerable admiration. Yet Hazlitt also thought that this idol, great though he was, held a more limited kind of attraction than Scott did. While one "casts his descriptions in the mould of nature, ever-varying, never tiresome, always interesting and always instructive", the other made "everlasting centos out of himself". And in prose rather than verse, that difference was even more pronounced. "All is fresh, as from the hand of nature" in Scott's Waverley; Byron's formal prose is "heavy, laboured, and coarse".

The key word here is "formal" ��� by contrast, Richard Lansdown argues in his Cambridge Introduction to Byron, that "Even if Byron's poems had never existed he would remain a classic author". Byron's informal writings ��� his letters and journals ��� constitute "one of three most significant informal autobiographies in English", alongside Pepys's diary and Boswell's journal. (That male, libido-driven trio prompts me to ask: who are the best female English diarists and letter-writers? Virginia Woolf? George Eliot? Sylvia Townsend Warner?)

The earliest letter here dates from 1798: "Dear Madam, My Mamma being unable to write herself desires I will let you know that the potatoes are now ready and you are welcome to them whenever you please". The last dates from only a few days before his death in 1824: "As the Greeks have gotten their loan ��� they may as well repay mine . . .". What comes in between? "I have been up all night at the Opera ��� & at the Ridotto & it's Masquerade ��� and the devil knows what ��� so that my head aches a little ��� but to business." Some of that, certainly. More, too, though, about his travels ("Cadiz, sweet Cadiz!") and his poetry ("in no case will I submit to have the poem [Don Juan] mutilated"). And escaping England, notoriety and the rest.

Lansdown's new selection of Byron's Letters and Journals will be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS. In the meantime, for the latest episode of our podcast TLS Voices, here's our own selection from that selection. Modern Hazlitts, beware: alongside expressions of literary scorn (for most modern poets and for Shakespeare, despite the many allusions that pepper Byron's correspondence) and personal passion (for Teresa, Contessa Guiccioli), it includes a Byronic ascent among the "cloud-capt" Alps. A lofty eminence, indeed.

May 28, 2015

Kingsley Amis���s ���feast of fun���

Anthony Hobson in his study, c.1970 ; Christies's Images LTD, 2015

By LAURA FREEMAN

���Keep a diary���, is the advice attributed to both Mae West and Margot Asquith, ���and one day it will keep you.��� Keep, too, the books of great men and women and do not neglect to have them signed. This is the postscript the late Anthony Hobson, bibliophile, expert on antique bookbindings and author of almost 200 reviews for the TLS, might have added.

Hobson���s collection helped him out of financial crisis on more than one occasion. It was his mentor, Cyril Connolly, who advised: ���Do not hesitate to ask authors you meet to sign their books for you���.

In 1996, anxious about money, Hobson culled from his collection books by seventeen authors in a 323-lot auction. Out went W. H. Auden, T. S. Eliot, Robert Graves, Graham Greene, George Orwell, Evelyn Waugh, Virginia Woolf and W. B. Yeats. There were, however, authors with whom he could not part. He kept works by Federico Garcia Lorca and the letters of Ronald Firbank ��� he was still working on those. And he could not easily part with books by his friends.

Hobson died last year, aged ninety-two, ten days after his swansong review had appeared in the TLS. He had outlived all but one of the writers he collected. V. S. Naipaul is, at eighty-two, still writing.

It is only with Hobson���s death that his collection of works by friends is to be broken up. As a recent NB column in the TLS pointed out, on June 10, 250 lots will be auctioned at Christie���s South Kensington.

There are books by Harold Acton (���For Anthony Hobson with the hope that I may eventually write something worthier of his fine taste���); by Cyril Connolly (���Anthony from Cyril ��� This edition was a flop because I would not put my photo on the cover ��� 350 copies sold!���); and by Christopher Sykes (���Haven���t read it since. Shan���t again. C.���).

Anthony Powell signed each of the twelve volumes of A Dance to the Music of Time as they were published: ���Anthony Powell after a delicious luncheon���; ���Anthony & Tania after a very delicious luncheon���. Regrettably, Powell dedicated six of the volumes to Hobson���s wife Tania (spelt incorrectly) and only three to Tanya (spelt correctly).

V. S. Naipaul���s dedications do not vary: ���V. S. Naipaul for Anthony Hobson��� inside The Mystic Masseur; ���V. S. Naipaul for Anthony Hobson��� inside A Flag on the Island; and again ���V S Naipaul for Anthony Hobson��� inside In A Free State.

The greatest pleasure of the auction catalogue is in the flyleaf dedications from Kingsley Amis, a friend of many decades. Amis���s inscriptions are self-effacing and pleasingly puckish.

On the front free endpaper of Amis���s first published work Bright November, the author has written: ���Anthony from Kingsley, these abnormally unpromising first fruits���. The dedication inside Springtime: An anthology of young poets and writers is more confident: ���My first appearance ��� of any respectability ��� in book form (I think)���.

Inside What Became of Jane Austen? And Other Questions is the laconic: ���Yet another feast of fun for Anthony, from Kingsley���. Inside Socialism and the Intellectuals, Amis has scored though his own typed name and written: ���Ah well, too late to repudiate now.��� By the time he came to sign The Old Devils in 1986, he appeared to be running out of steam: ���Here we are again ��� Anthony���.

The dedication inside A Spectator Miscellany reveals Amis suffering a pang of regret: ���Anthony from Kingsley (a bit hard on L. Lee, perhaps.)���. The anthology contained Amis���s essay ���Is the Travel-Book Dead?��� ��� a critical review of Laurie Lee���s A Rose for Winter. Amis thought Lee���s deliberate seeking of discomfort absurd: ���it is silly to sleep on straw in the inn yard if you can get hold of a bed; and while it is no doubt better to be gay and have sores than to be ungay and not have sores, it is better still to be fairly gay and not have sores���.

Amis did not take criticism of his own work with good grace. His 1977 novel Harold���s Years is inscribed: ���Auberon Waugh was very shitty about this . . . ���

There is a thrill in the intimacy of these inscriptions: they reveal something of the mood of the author at the time of signing ��� anxious, bombastic, rueful ��� and of the confiding nature of the friendship. We might imagine both men in high spirits when Amis wrote inside the covers of Lucky Jim, his most enduring novel: ���Anthony from Kingsley, on a splendid day in March���.

May 26, 2015

Oh Hull

By MICHAEL CAINES

In 1996, the Scottish poet Kathleen Jamie wrote a review of four new books in the TLS, by writers who seemed distinguished by some idiosyncratic connection to their chosen territory. (Or whose territory had chosen and shaped them, you might say.) Between the ���short, unpretentious��� poetry of Siobhan Campbell and the ���fresh and exciting��� debut of Alice Oswald came a posthumous publication: How It Turned Out: Selected poems by Frank Redpath. His ���sustaining words���, Jamie noted, were ���Humber���, ���North���, ���Hull��� and ���friends���. She mentioned a ���fond and insightful��� introduction by Sean O���Brien which revealed that Redpath ���had little interest in publishing���. ���But How It Turned Out will ensure he receives some of the recognition he never sought.���

Well, a Redpath poem did receive a little belated recognition last week: it appeared in the TLS as a previously unpublished poem by Philip Larkin. That���s right: contrary to what we and the Larkin scholars who inspected it believed, ���In and Out��� isn���t by Larkin, after all. Yet it seemed so perfectly (too perfectly?) Larkinesque. And as Tom Cook wrote in last week���s issue, it ended up as two halves of loose typescript tucked into one of Larkin's archived workbooks at the University of Hull.

How did that happen?

As Sean O���Brien recalls (see his letter in the forthcoming TLS), it was back in 1982 that Douglas Dunn put together an anthology called A Rumoured City, celebrating the ���new poets��� of Hull. The young guns included Peter Didsbury, Douglas Houston, Ian Gregson and Sean O���Brien himself. There were contributions from a certain Frank Redpath. And Philip Larkin provided what William Scammell called ���one of his dead-pan prefaces���. That was in the TLS; Scammell thought Didsbury, Houston, O���Brien and Gregson were the ones to watch. Frank Redpath, meanwhile, had ���clearly modelled himself on Larkin���.

In fact, as Jean Hartley notes in Philip Larkin, the Marvell Press, and Me, Redpath was ���by far the oldest of the ten poets represented���. Born in 1927, a soldier in the late 1940s and then a journalist, he had produced a ���small but steady��� stream of poems since the 40s. Apparently, though, until Ted Tarling created the poetry magazine Wave in the 1970s, ���he had only once been able to bring himself to seek publication���.

A Rumoured City aside, it seems publication sought out Redpath in later years. Tarling would later publish To the Village, a collection of thirty-six Redpath poems, in 1986; the posthumous selection reviewed by Kathleen Jamie was the Rialto���s first venture into book publishing. Another poetry magazine, Stand, published Redpath���s ���I saw a child hold up his finger . . .��� a year later, with the sheepish comment, ���This poem has surfaced from the magazine���s archives where it may have spent some considerable time���.

Redpath���s print-shyness partly explains why outsiders could mistake him for just another of the post-Larkin crowd, as Phil Bowen did when he referred to the ���new poets from Hull��� in A Gallery To Play To: The story of the Mersey poets. And no, at the time of writing, Wikipedia doesn���t have an entry for ���Redpath, Frank��� or list him among the writers associated with that ancient city in the East Riding of Yorkshire. ���My day, thank God, unmentioned on the news���, indeed, as he once noted.

Insiders could tell a different story. Houston recalled that he was an ���extremely decent man��� who had written ���stories for children���s comics��� as well as poetry. It was on Redpath���s advice that another Hull writer, Peter Everett, got himself out and down to London. O���Brien gives some sense of his territory in ���To the Unknown God of Hull and Holderness��� (���God of the windy bus shelter and the flapping hoarding���; ���God of the infilled drainsite . . .���), which is dedicated to him. In a garden not far from the Humber estuary, meanwhile, a statue of the apostle Peter sits, heavily pondering his denial of Christ and his redemption, in Redpath���s words:

Once quicksand man, then called

A rock; three times denied

The name who gave my name:

The moving ghost filled all

My shifting, made me firm.

So credit where it���s most definitely due: to Sean O���Brien for recalling A Rumoured City (in which Dunn says ���In and Out��� ���evokes November in the moody long gardens of Hull���s Avenues district���) and setting the record straight.

The best part of the story, however, is this. Larkin didn���t have Redpath���s unqualified admiration ��� as O���Brien has recalled, the lesser-known poet ���once called Larkin a political ignoramus across the dinner table, and Larkin���s letters suggest that he was not far short of the mark��� ��� but it does seem that they regarded one another���s poetry very highly. Jean Hartley recollected how Larkin was publicly supportive of A Rumoured City, but privately much less complimentary about it. To Frank Redpath he said: ���Yours are the only poems in the book I would have been glad to have written���.

We cannot know if Larkin meant that, of course, but it���s a suggestive remark, given how securely ���In and Out��� could be identified as Larkin���s own, on the basis of both close readings and external evidence. As with their political views, though, it exposes the differences between the two of them as much as the similarities. Hartley continues:

���Frank���s initial response was to feel thrilled at being complimented by a poet whose work he so much admired. But the feeling changed to sadness as he thought of the words Philip had used, with their implication of increasing isolation from the work of the younger poets coupled with a wistful lament for a fulfilment which he was hardly ever again to enjoy.���

Update: Here's "In and Out" by Frank Redpath (not Philip Larkin), with a brief introduction by Sean O'Brien.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers