Byron in prose

By MICHAEL CAINES

"He is like a solitary peak, all access to which is cut off not more by elevation than distance", William Hazlitt wrote of Lord Byron. "He is seated on a lofty eminence, 'cloud-capt', or reflecting the last rays of setting suns; and in his poetical moods, reminds us of the fabled Titans . . . . He scorns all things, even himself. Nature must come to him to sit for her picture ��� he does not go to her. . . ."

Hazlitt's sublime Byron appears in The Spirit of the Age in the course of a comparison with Sir Walter Scott, the contemporary poet for whom Byron himself expressed the most considerable admiration. Yet Hazlitt also thought that this idol, great though he was, held a more limited kind of attraction than Scott did. While one "casts his descriptions in the mould of nature, ever-varying, never tiresome, always interesting and always instructive", the other made "everlasting centos out of himself". And in prose rather than verse, that difference was even more pronounced. "All is fresh, as from the hand of nature" in Scott's Waverley; Byron's formal prose is "heavy, laboured, and coarse".

The key word here is "formal" ��� by contrast, Richard Lansdown argues in his Cambridge Introduction to Byron, that "Even if Byron's poems had never existed he would remain a classic author". Byron's informal writings ��� his letters and journals ��� constitute "one of three most significant informal autobiographies in English", alongside Pepys's diary and Boswell's journal. (That male, libido-driven trio prompts me to ask: who are the best female English diarists and letter-writers? Virginia Woolf? George Eliot? Sylvia Townsend Warner?)

The earliest letter here dates from 1798: "Dear Madam, My Mamma being unable to write herself desires I will let you know that the potatoes are now ready and you are welcome to them whenever you please". The last dates from only a few days before his death in 1824: "As the Greeks have gotten their loan ��� they may as well repay mine . . .". What comes in between? "I have been up all night at the Opera ��� & at the Ridotto & it's Masquerade ��� and the devil knows what ��� so that my head aches a little ��� but to business." Some of that, certainly. More, too, though, about his travels ("Cadiz, sweet Cadiz!") and his poetry ("in no case will I submit to have the poem [Don Juan] mutilated"). And escaping England, notoriety and the rest.

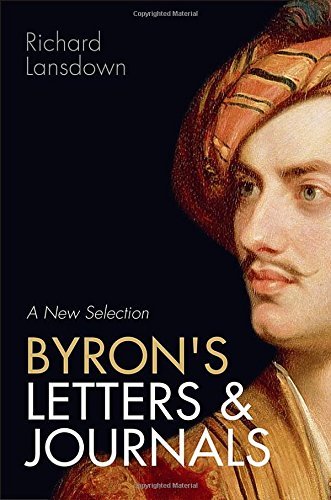

Lansdown's new selection of Byron's Letters and Journals will be reviewed in a future issue of the TLS. In the meantime, for the latest episode of our podcast TLS Voices, here's our own selection from that selection. Modern Hazlitts, beware: alongside expressions of literary scorn (for most modern poets and for Shakespeare, despite the many allusions that pepper Byron's correspondence) and personal passion (for Teresa, Contessa Guiccioli), it includes a Byronic ascent among the "cloud-capt" Alps. A lofty eminence, indeed.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers