Peter Stothard's Blog, page 27

April 16, 2015

Gwyneth Paltrow's steam bath and other ways of avoidi...

Gwyneth Paltrow's steam bath and other ways of avoiding the subject of shitting in ancient Rome. From this week's Spectator. http://www.spectator.co.uk/books/9499032/how-the-romans-went-about-their-business/

Translation into English – and instant translation

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

In their newly published report, Publishing translated literature in the United Kingdom and Ireland 1990–2012, Alexandra Büchler and Giulia Trentacosti, of the Mercator Institute for Media, Languages and Culture at Aberystwyth University, write “The absence of data on published translations and the low literary translation output has always set the United Kingdom and Ireland aside from the rest of Europe”. To explore this further, they have “embarked on the task of collecting and analysing translation data” and has come up with the following:

The oft-quoted figure of 3 per cent, that being the proportion of translated books to English-language books (over the period 1990–2012), is accurate.

This compares with 12 per cent in Germany, 15 per cent in France, 19 per cent in Italy and 33 per cent in Poland.

“Some languages, both European and non-European, are very poorly represented, notably Eastern European languages”.

Literary translations are slightly higher, at 4 to 5 per cent. That would be novels.

In Germany, English was the “leading source language at 63% with French in second place at a mere 10.2% share”. (In France, English scores 61 per cent, with Japanese second at 13 per cent.)

The report points out that there are six available English translations of Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. “Following Three Percent’s logic, should only one of these be listed and the remaining ones ignored? Does not each of these translations in fact represent a ‘new voice’?” I would say it does.

The report does not draw any significant conclusions. My views, for what they’re worth, are that the UK and Ireland will always score quite low when it comes to translated literary work for the simple reason that we have the whole anglophone world at our disposal. Having said that, we could certainly translate more, particularly from the languages the report says are neglected; above all, we could perhaps translate more quickly. As I pointed out in the TLS earlier this year, Michel Houellebecq’s new novel Soumission was available in a German translation in the same month as it was published in France (it's scheduled to appear in English this September). That meant that German readers who had read about the fuss it was causing in France could immediately go out and buy a German translation and make up their own minds. And Kazuo Ishiguro’s new novel The Buried Giant appeared in a French translation (as Le Géant enfoui) one day after British publication. Indeed, Ishiguro is in France at the moment, promoting his new and newly translated novel.

April 10, 2015

King Lear at The Rose Playhouse

By ROZ DINEEN

John McEnery as King Lear

The Rose was the first purpose-built theatre in Southwark. Before The Globe, before, even, The Swan, The Rose stood among the bear-baiting, whore-housing, dens and iniquities. Doctor Faustus was staged there, as were both the Henry VIs and Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy. By 1606 the space had been abandoned, it was repurposed, built over and then lay undiscovered until the late 1980s when an office block came down above it.

Our offices being located where they are (sort of on top of the huge and morphing London Bridge station), the Rose is our local theatre and has been well-frequented by TLS staff. It is still an archaeological site, a big hole, an excavation, partly unroofed. A viewing platform has been installed – like Juliet’s balcony – over the damp concrete scene. It is quite remarkable that on this platform (not even a wooden O) it is just about possible to fit fifty seats and a production, let alone an impressive and moving staging of King Lear. The Malachites company, here directed by Benjamin Blyth, have done exactly this.

The benefits of an intimate Lear are in evidence from the start. The King (John McEnery) holds court to carve up his kingdom for his daughters and “unburden'd crawl toward death”. It’s a scene that has been known to invite over-acting, but here there is no eye-rolling, there are no meaningful looks; with the audience in such close proximity, everything can be under-played, the daughters’ slightest smirks and hesitations are detectable. Goneril, Reagan and Cordelia (respectively Claire Dyson, Orla Jackson and Emma Kirrage) are smart, subtle and individuated. Lear would give the most opulent third to his youngest, Cordelia, but first she has to play his game, she must delight him with some ornate language. Cordelia offers “nothing”.

The play’s sub-plot of Edgar (Ludovic Hughes) and Edmund (William De Coverly), the legitimate and illegitimate sons of the Earl of Gloucester (Brian Merry), is not so much a sub-plot in this production: the three actors in this triangle alone could hold the attention for the ninety-minute running time (yes, ninety minutes, no heating and no toilets means no interval and cuts; but the play has been gently shrunk, rather than butchered, even if the war does come on at a bit of a gallop). The music (original compositions by Dr Deborah Pritchard and Danielle Larose) emanates throughout from “off stage”, which is a small corner of the excavation, just visible. From this corner the great storm that will crack Lear’s mind begins to grow, in voice and instrument.

During the storm, the whole excavated space is brought into play as Lear, his Fool (Samuel Clifford), Kent (David Vaughan Knight) and Edgar (hiding under the cover of madness), each unnaturally thrown out of his society, leave the platform and meet in the wild, at the back of the dug-out waterlogged old theatre. From here they are at liberty to scream against the wind and really move. But out of the elements and back on the platform, we see a perfectly under-played Fool who is usurped by Edgar and devastated for Lear. We also witness McEnery conveying the madness of an old man up close, which here is frightening, as it should be.

It is hoped that in 2016 the excavation at the Rose site will be finished, and eventually a 250-seat theatre will take up the space. I’d go now, before the crowds get there, while it is still uncovered.

King Lear runs at The Rose Playhouse until April 30.

April 9, 2015

Elegant variation, anyone?

"la cité phocéenne” (otherwise known as Marseille)

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Fowler has fun with the concept of elegant variation in his Modern English Usage: “It is the second-rate writers, those intent rather on expressing themselves prettily than on conveying their meaning clearly, and still more those whose notions of style are based on a few misleading rules of thumb, that are chiefly open to the allurements of elegant variation.” Elegantly put. He clearly felt strongly about it: “There are few literary faults so widely prevalent, and this book will not have been written in vain if the present article should heal any sufferer of his infirmity.” Over the course of a couple of pages he provides examples, of greater or lesser egregiousness (I’m sure he would have disapproved of that phrase), of the practice, and explains why they won’t do.

I don’t think Fowler has been translated into French, and don’t know if there’s a French equivalent. I should know. If there is, it’s probably not to be found in the editorial offices of Le Monde if their articles are any indicator. Here are a few of their favourite elegant variations, from headings and articles themselves: Diego Maradona was once “le capitaine de l’équipe parthénopéenne”, i.e. Napoli. Other football teams include “Les Helvètes” (the Swiss), “Les Fennecs” (Algeria) and of course “Les Bleus” (France). The Irish rugby team, meanwhile, is “la XV du Trèfle” (clover), while the English are “la perfide Albion”.

Marseille is often referred to as “la cité phocéenne” (as in Phoenician; “la cité phocéenne reste une république bananière”), Toulouse as “la ville rose”, while Brasilia is “la cité carioca” (I admit I had to look that one up). Japan is “L’Archipel” with Tokyo “la capitale nippone”. China is elegantly varied as “l’empire du Milieu”, New York “la Grande Pomme”, Rome “la Ville éternelle” of course. Lebanon is, bien sûr, “le pays du Cèdre”, while Jordan (another country in "le Levant") becomes “le royaume hachémite”,and Morocco “le royaume Chérifien” (some thought must go into these!).

Then there is the taint of political incorrectness: Beijing and Mumbai are still referred to as Pékin and Bombay, in seeming defiance of conventional naming. And the phrase “un kamikaze taliban” strikes me as particularly crude. Did no one think to change that?

Back to perfidious Albion: in the late 1980s, Christopher Hitchens used the phrase “rotund felines” in an article, presumably about greedy City bankers. It struck me as comical and consequently has stayed with me. Clearly he wanted to avoid writing “fat cats”. The beauty of his phrase is in the fact that the reader can’t be sure whether it was deliberately arch, or an attempt at variation by a notably stylish writer. Probably a bit of both. Or maybe – and this strikes me as unlikely – he was going for euphemism: “a mild or vague or periphrastic expression as a substitute for blunt precision or disagreeable truth” – Fowler.

Thinking up inelegant variations can relieve the tedium of office life (and I’m sure not just in the offices of the TLS). The more arch the better, in my view: “assail yourself to the point of unconsciousness”; “desist from proceeding in that direction”; “authenticity has been achieved”; “I’ve witnessed what you performed”, and so on. I hope I don’t need to translate any of these. Can you offer any others?

April 4, 2015

Houellebecq on form

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Michel Houellebecq’s most recent novel, Soumission, is really very good. As is well known, it was published on the day of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, in which the novelist lost one of his friends, the sixty-eight-year-old economist Bernard Maris. It’s inevitable that the publication of a mere novel should have been completely overshadowed by such events, and noteworthy that France’s leading left-leaning paper Le Monde gave the book a distinctly lukewarm review. The paper has given Houellebecq acres of coverage over the course of his career, so this was a significant thumbs-down.

But, for what it’s worth, I think Soumission is far superior to his last novel La Carte et le territoire (2010; The Map and the Territory), which walked away with France’s most prestigious literary prize, the Goncourt. As French editor of the TLS I feel mildly embarrassed that it’s taken me until now to read Soumission; but then I was rather put off by the last effort. (There was also the small diversion of the film that came out last year, The Kidnapping of Michel Houellebecq, which seemed to me a complete indulgence of the author.) Russell Williams reviewed Soumission for the TLS in March; he had some well-argued reservations which I don't entirely share.

It seems to me that where Houellebecq excels in his most recent novel is in presenting quite complicated ideas in a lucid and highly readable style. The writing is as sharp as it has ever been, and will present quite a challenge to his English translator. The conceit of having, as a central character, an expert on the work of the quirky symbolist novelist J.-K. Huysmans is a brilliant one; and Houellebecq is always illuminating on Huysmans: he knows his work well.

Meanwhile this insight, late in the novel, was worth the admission price alone, as they say: “. . . these hideous [faculty] buildings had been constructed during the worst period of modernism, but nostalgia has nothing to do with aesthetic sentiments, it’s not even linked to a happy memory, one is nostalgic for a place simply because one has lived there, regardless of whether it was good or bad, . . .” How true.

April 1, 2015

English as she isn't spoke, part 2

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Ah, the joys of station announcements. There have been plenty of those at London Bridge recently, a stone’s throw from the TLS’s new offices, as the station undergoes major rebuilding (which will take three years). The punctuality rates of trains (never very good) have fallen through the floor, as the picture above demonstrates (you will need to magnify it, but suffice it to say that the word "Delayed" occurs frequently). This is all happening at the UK’s fourth busiest rail terminal.

A couple of years ago, I posted about the excruciating genteelisms that (mostly pre-recorded) station or train announcements trade in, along the lines of “. . . customers who pay the additional premium to enjoy first class travel”.

Here are a few more:

“Train services are experiencing delays”. Can an inanimate, albeit moving, object “experience” something? Might not “trains are running late” do fine?

There are the ones that just go a bit wrong: “I apologize for any delay to your service [who’s “I” by the way?]. This is due to awaiting a train crew.” Or “This is in reaction to a shortage of available train crew.” “In reaction to”?

I also like: ”We apologize for any inconvenience this cancellation may cause” (my italics). Is it not a given that a late-running train will cause inconvenience?

And then there’s my favourite: “please be advised”, as in “Please be advised that your journey time will be extended. This is due to . . .". Or “Please be advised that this service has been cancelled” and “You are advised the train will be delayed a short while . . .".

Of course the trains themselves are frequently “subject to delays or platform alterations” (which makes me feel sorry for the trains; on the face of it, maybe they are sentient beings after all).

Tenses can be strange: “The 8:59 is being delayed.” Is being? “It has become necessary to cancel the. . .". (In a similar vein, footballers, when interviewed after a match, tend to use the past continuous rather than a more standard tense, as in “I’ve gone in there with my studs up and I’ve caught him. I’ve apologized to the lad . . .".)

Finally, there are the often engaging announcements made by the train drivers or guards/inspectors (better known as “revenue protection officers”). They are usually worth listening to, conveying as they do a sense of mystery: “This is the first train to leave Brighton for London Bridge for some considerable time . . .“.

Or how about this?

“We will endeavour to get you to your stations as quickly and safely as possible”. Reassuring.

March 27, 2015

The Kids Are Alright

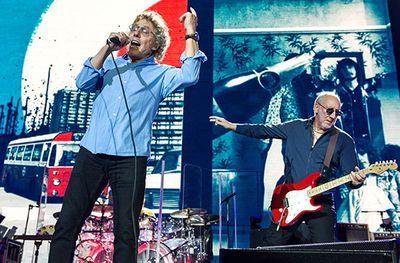

Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend, March 2015 - Brian Rasic/Rex Features

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

It was a farewell tour, a swansong, a celebration of fifty years in the music business. And as I had never seen The Who live I didn’t want to miss it. Having two days earlier heard a sublime performance of Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht by the Sussex-based string sextet Ensemble Reza (that’s the kind of eclectic guy I am), I wandered along to the soulless concrete bowl that is the O2 Arena. There, in residence for two nights, were the veterans Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend, and their younger band members (including the guitarist Simon Townshend, younger brother of Pete). They made sure they left us something to remember them by.

The Who have always struck me as quintessentially British (with a few Celtic tinges such as in the song “Baba O’Riley” on Who’s Next), from their Mod appropriation of the Union Jack to their blokeish wit: Daltrey jokingly complained that “they’ve made us play two nights running. Football teams don’t have to do that. But WE DELIVER! Unlike a few football teams I could name”. Later Townshend started to rubbish one of his own songs, “Substitute” – “that bit in the middle’s not very good, I should have cut it”, or words to that effect. And then there’s “Pinball Wizard” (rather well covered by Elton John many years ago), with its socio-topographical references: “From Soho down to Brighton, / I must have played them all” . . . There was a video backdrop of parka-wearing Mods on Lambrettas riding over the Sussex Downs to Brighton, all nicely evocative of the band’s formative years.

The O2 may be soulless, but it has a good acoustic: incompetent musicians will probably be found out there. And The Who are very far from incompetent, which would explain why they’ve survived fifty years (without, of course, their early casualty, madcap drummer Keith Moon and the longer-lived, slightly eccentric bassist John Entwistle). Daltrey’s voice still has astonishing power and range even if his movements on stage are necessarily restricted (although he can swing a mic cord with aplomb). Townshend, in dark glasses and comically large white trainers which enabled him to leap around windmilling like a twenty-five-year-old, played superbly. I hadn’t expected him to be quite so potty-mouthed: “I wrote this one before most of you were even f***ing born!” (not true). There was quite a lot of that kind of banter. It was funny: Townshend playing the grumpy old man, but with huge energy.

From “My Generation” (yes, I know, it’s absurd now, but still a classic), to songs from Quadrophenia, to, inevitably, “Won’t Get Fooled Again”, they did indeed deliver. I’m sure if they had just played the entirety of Who’s Next (that rare thing, an album without a dud song on it), the audience would have been very happy. As it was they performed for a good two hours, without a break of course. The Who embark on a marathon farewell North American tour later in the year. I should think they’ll go down a storm. As Daltrey left the stage, he implored his audience: "Be lucky!"

March 26, 2015

Richard at rest

By DAVID HORSPOOL

It wasn't a funeral service. That was emphasized from the beginning. But walking into a packed Leicester Cathedral and milling about, ten feet away from a coffin while someone found me a seat, it certainly felt like one. History editors don't often get to attend global news events, certainly not in any official capacity, so the chance to go to the reinterment of Richard III this morning was too good to miss: especially for me, as I also happen to be putting the finishing touches to a book about the king (yes, I know the world probably doesn't need another book about him, but I'm afraid what the world needs and what the world gets aren't necessarily the same thing).

The two and a bit years since Richard's remains were discovered in the most celebrated car park in England (a little more time than he spent on the throne), yards away from the cathedral, have been filled with fractiousness.

First, we had the doubts about the accuracy of the identification. Then there was the spat over where the bones should go, which led to a court case started by the "Plantagenet Alliance", who wanted him to be reburied in York (I attended a day of that, too: a bizarre mixture of formality and on-the-hoof historical blether). Next came the inevitable signs of strain in the awkward marriage of enthusiasm and academe that had made the discovery possible. Representatives of the Richard III Society, and in particular Philippa Langley, whose inspired detective work and advocacy had persuaded University of Leicester archaeologists to start digging, began to complain that their contribution to the great discovery was being written out. All that, before we even begin to contemplate the awkward fact of Richard's reputation. You wouldn't know it in Leicester, but historians still tend to categorize him as a usurper and probable child murderer. (Why, you may ask, when the camera picks out the smiling faces of children from Richard III Primary School, did someone think it was a good idea to name a school after such a person? Even if he was innocent of the charge, it seems an odd association to make.)

The Church might say that God welcomes all, but did that mean the nation had to grind to a halt for Richard? This morning, however, on the first day of the new year as it was reckoned in the Middle Ages, the capacity of British pageantry, and a bit of star quality to smooth over the cracks, was on impressive show. I have never seen quite so many different uniforms up close. As well as a riot of chasubles and copes on bishop, archbishop and dean, there was the Orator of the University of Leicester in academic gown and one of those hats that Mark Rylance's Thomas Cromwell doffed with such elegance; there were two Yeomen of the Guard (aka Beefeaters); I sat behind two army officers, one Royal Air Force Squadron Leader (I know his rank because his seat card fell on the floor and I got a glimpse) and a senior naval personage. There was a man in a full-bottomed wig, and men in spurs (but no armour, though some women behind the barriers outside wore full medieval head-dresses) and a surpliced choir forty strong.

Across the aisle from me, Benedict Cumberbatch (Richard's cousin sixteen times removed) and Robert Lindsay (no relation, yet) appeared to be comparing Yorkist lapel badges, while around the cathedral men and women who have become much bigger stars in Ricardian eyes could be spotted: Langley pretty much wearing widows' weeds (again); John Ashdown-Hill, the historian and geneaologist who first traced the king's bloodline, and who had donated a crown for the occasion (apparently he had one spare; he was the man who happened to have a royal standard in his boot to wrap the cardboard box containing Richard's as yet unidentified remains, so we shouldn't be surprised).

And, I suddenly realized, two seats away was Dominic Smee, the young star of a documentary about Richard who has been described as his body double – he suffers from the same spinal condition, scoliosis, to the same degree as the king. It was a chance to confirm that, contrary to a Ricardian claim I had heard only the night before, Richard's disability would have been clearly, if only slightly, visible through clothing.

It was not a time to revisit Richard's own contested reputation, though the swiftness with which both eulogy and sermon vaulted over those fraught weeks in which Richard seized (or "was offered") the throne was a wonder to behold. I was slightly confused by the idea that only in 2009 had an account of a medieval reinterment been found, in the British Library, as a very full narrative of the ceremonies to transfer Richard's own father and brother, killed at the Battle of Wakefield, to a more honourable resting place at Fotheringhay, has long been known. I plan to look into that. (Update: I have. What hadn't survived was details of the service -- and music -- at such a ceremony, so the discovery by Dr Alexandra Buckle of a transcription of the reinterment rite for Richard Beauchamp, fourteenth-century Earl of Warwick, certainly was a uniquely useful find.)

One more reinterment troubled me: when workmen found bones at the foot of a staircase in the Tower of London in the seventeenth century, and it was concluded that these were the remains of the "Princes in the Tower", Edward V and Richard of York, these too were offered a more dignified reburial, in Westminster Abbey, but nothing like the orgy of commemoration that has attended the man accused of their murder. And, pace Carol Ann Duffy, whose poem cousin Benedict read so stirringly, Richard's name had been carved before. Henry VII paid for a tomb and epitaph in 1494, years after Bosworth. It wasn't a showy thing, just £10 worth of alabaster (around £5,000 today). But perhaps it was more in proportion with the achievements of a man who sat on the throne for two years, and spent a large proportion of that time desperately trying to hold on to it.

On the train down from Leicester, I expected real life to return with a bump, but a little bit of the surrealism persisted. The Countess of Wessex swept past me in the waiting room in her killer heels, attended by a Sikh railwayman and one of those spurred officers, as well as an indeterminate number of brittle ladies-in-waiting. They had a carriage to themselves. Perhaps the Countess might have been asked to make room for the Archbishop of Canterbury, who squeezed past me as he said to a member of his staff, "No, I don't think I do have a seat reservation".

March 24, 2015

Heath Robinson’s humours

Publishers have some inscrutable habits. Among the easiest to understand, though, is their traditional turn to "humorous books" around December. The TLS's NB column reports every season on how the till-side piles of such publications can lead to a bad bout of the "Christmas giftbook blues" – Aunt Sally won't thank you for that side-splitting copy of Is It Just Me or Is Everything Shit?, you know.

The family had more innocent options in 1936. You could have lightened the low, dishonest mood with Dear Sir, Unless . . ., written by Nathaniel Gubbins and illustrated by William M. Hendy – a "Guide to Dodging Income Tax", hovering "a little uncertainly", according to the TLS review of the time, "between leg-pulling and semi-serious counsel". Or could the authors of 1066 and All That have raised a laugh with their Garden Rubbish? Not likely: "unrelieved nonsense", said the Lit Supp.

I'm quoting here from a round-up of eight humorous books by an unknown reviewer, who noted that only one of them named its illustrator on the cover, How To Live in a Flat, written by K. R. G. Browne and illustrated by a cartoonist whose work has just been, in the well-worn phrase, "saved for the nation": William Heath Robinson. . . .

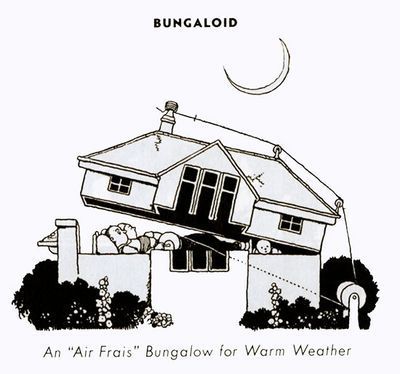

Born in 1872, Heath Robinson initially wanted to be a landscape painter, but illustration was the (better-paying) family business. He soon acquired a nickname, "The Gadget King", for the line in imagined contraptions for which he continues to be celebrated – spectacular mechanisms, ingenious spaghetti medleys of pipelines, eccentric, elaborate contrivances for performing simple tasks, and the like. He could be more economical with his sight gags, though, as in the "Bungaloid" pictured above, which appears in How To Live in a Flat, and this "Baby Grand" from the same source:

Not that Londoners then or now could take such cartoons entirely as a joke (I tip my hat to the fellow editor who found this on YouTube):

The Bodleian Library recently reissued How To Live in a Flat alongside another from the same collaborators, How To Be a Motorist (1939), in which the enthusiast for the open road is advised on arcana such as how the thing works ("without brakes it would be highly impolitic to use the engine"), accommodating a large family (try the "Expandocar", constructed on the "opera-hat principle"), and the selection of a "radiator mascot" (a "little rubber replica of the Home Secretary" or a "small-scale reproduction, in solid granite, of Battersea Power Station"?). Interestingly for admirers of the large-scale Heath Robinson contraptions, Browne confesses that they are neither of them "skilled engineers" – "though I can open a tin of peaches with the best, while his mastery of the corkscrew is much admired by the local Dorcas Society".

Meanwhile: the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Art Fund have contrived to help decisively with the purchase of a collection of 410 Heath Robinson paintings and drawings, including his wartime cartoons (in which he explores the obvious comic potential of the goose-step and espionage by carrier pigeon, among other things). This collection will now go to the William Heath Robinson Trust, which has also received £1.13 million from the Heritage Lottery Fund to establish a museum in his name, at his house in Pinner. It looks as though this will give the museum a total of nearly 1,000 original artworks to display, but also another £200,000 still to raise if their ambitions are to be realized.

Perhaps it won't be forgotten, among those weighing up whether or not to chip in, that while there can be no denying the main reasons for Heath Robinson's popularity, that he also illustrated works by Shakespeare, Rabelais, Edgar Allan Poe and Kipling – the "designs" for the last, Laurence Binyon wrote in the TLS, being "unequal" but sometimes appropriately "grandiose" and an enrichment of the verse:

There is also Heath Robinson's own twee yet charming story Bill the Minder ("The pictures are irresistible – deliciously real children", ran the TLS review, "dreams of beautiful colour, and bits of riotous grotesquerie, unsurpassed even by Lear . . . an orgy of gorgeous nonsense"), as later adapted as a children's television programme, and selectively reproduced below. Maybe one Christmas an enterprising publisher will engage to put these little inventions back into print, too.

March 23, 2015

Evergreen John Ford

Owen Teale as Bassanes and Amy Morgan as Penthea; photograph by Marc Brenner

By THEA LENARDUZZI

My heart goes out to the poor King of Sparta. All he wants is a court full “revels and disport; the joys of Hymen . . . . No sounds but music, no discourse but mirth!” What he gets instead is one ravaged by duplicity, indecision, depression, jealousy, revenge and, possibly, post-traumatic stress disorder. This is a central irony around which all others circulate in John Ford’s The Broken Heart, a play in which nobody gets what they want and happiness and propriety are rarely more than a charade. Caroline Steinbeis’s production is the latest in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse’s “Extreme Love” season which has already featured stagings of Ford’s best-known play, ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore, written a few years after The Broken Heart, as well as The Knight of the Burning Pestle and L’Ormindo.

As Martin Wiggins from Birmingham University’s Shakespeare Institute explains in his essay in the programme, Sparta was a city “known for valuing self-discipline over self-expression”. (I adore his appropriately inappropriate description of Orgilus as “cold on the outside, but passionately hot within . . . like a baked Alaska in reverse”.) Repression of all manner of appetites is the most prized skill here – no wonder Havelock Ellis published an edition of Ford’s plays in 1888.

So despite being saturated with love – between would-be lovers, brothers and sisters, daughters and fathers, soldiers – The Broken Heart is more four-funerals-and-a-wedding than the other way around. And the title’s use of the definite article is wittily undermined, given there is not a character in the play whose heart is not damaged – “Crack, crack” – to some degree.

At nearly three hours long, the Wanamaker’s latest offering is quite an undertaking (for the audience, not to mention the players). Though not far off its 400th anniversary, the play feels strikingly modern – this in spite of receiving the full Caroline treatment, complete with ruffs, crinolines and dripping candles. Steinbeis, whose background is almost entirely in new productions, has described writing out the play “line by line”, “translating it into my own English” in order to get closer to it. On stage, the language is Ford’s own, yet its ironies are evergreen and universal. In the age of social media where we’re all, apparently, “friends”, it’s worth sparing a minute’s thought for Ithocles who, after praising Orgilus’s friendship (“so dear, so fast”), has the carpet pulled out from underneath him – so fast.

And admirers of Ford who have read his plays will be pleased to see that The Broken Heart will be followed by Love's Sacrifice, to be revived by the RSC (and reviewed in the TLS) next month. The cracking of hearts continues.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers