Peter Stothard's Blog, page 31

February 7, 2015

Herring aid

Damien Molony as Spike and Olivia Vinall as Hilary in The Hard Problem. Photo: Geraint Lewis.

By MICHAEL CAINES

This novel of ideas question I've been fretting about – be honest, is it really something of a red herring?

In more general terms, that's a question D. J. Taylor both asks and answers in last week's Independent on Sunday, in response to The Hard Problem – or rather, in response to the responses to The Hard Problem, Tom Stoppard's (sorry) problematic new play, which recently opened at the National Theatre. Some people, as Taylor observes, will work themselves up over the unseemly prominence of "ideas" in, say, prose fiction or stage plays. Why can't novelists and playwrights just stick to nice characters and pretty plots? How dare we give "ideas" more prominence than they deserve . . .

The TLS contributor David Collard put it like this in a comment on my first post on this subject the other week: "Is there such a thing as a novel without ideas? Tread carefully . . .". A fair point; terms need to be defined. Taylor writes: a novelist might not be, in anybody's eyes, including their own, a "novelist of ideas", but at the heart of their work there may nonetheless lie "some kind of behavioural proposition". And as in pages, so on stages – and on canvases, picture postcards etc.

What we're dealing with when we talk about the novel, the play or any other kind of art of ideas, however, is a "rather specialised redoubt of the novel, drama or painting in which what exists on page, stage or canvas is there, primarily, and for all the attractions of its characters or the vigour of its impasto, to prove, or ventilate, a point". To this category belong the plays of George Bernard Shaw, the novels of George Meredith and George Eliot, and more. Not a shabby tradition at all, as far as writing in English goes, and one to be distinguished from any general notions about ideas that happen to turn up in novels. So whatever the opposite of a red herring is (help!), in this context, that's what this is . . .

I saw The Hard Problem for myself last week, and seem to be in the minority who enjoyed it. I know what my fellow reviewers mean when they use phrases such as "much to ponder" or even "information overload". But that comes with the intellectual territory, doesn't it? The play considers the question of consciousness, as well as the connected questions of the creation of life and the possibility of being selflessly good. This gives the ensemble, particularly Olivia Vinall in the lead, plenty of verbal heavy lifting to do, the Stoppardian disquisitions coming before the Stoppardian quips. It's performed suavely enough, but perhaps Nicholas Hytner has not pushed the actors into exploring their characters in as much detail and depth as possible. The result, I admit, is something Peter Kemp puts most succinctly in this week's TLS: The Hard Problem is "less drama than diagram".

All the same, as I said, I somehow contrived to enjoy The Hard Problem. Despite the awfully long words. What gives?

Well, I don't know. The jury's out and won't be back in until LSE week, I'm afraid. But for now: is it always true, as Taylor maintains, that "drama stands or falls on character, or if not character then human interest"?

For all its supposed faults, Stoppard's problem play confronts an intellectual problem directly and unapologetically. Such work isn't always welcomed by those with minds so fine, to adapt T. S. Eliot's words about Henry James, that no idea may be allowed to penetrate them. And so maybe those others who do not regard psychological realism as the principle or indeed only desideratum in a play or novels will always be in a minority – as with Meredith's small band of admirers, or the one Booker judge against the many.

Incidentally: turn the middle pages in this week's TLS, from the arts to the fiction section, and you'll be turning your attention from a new play to a new novel: Euphoria by Lily King. I haven't read it myself yet, but Jennie Erin Smith's review, "South on the grid", makes me want to do so before the LSE debate on February 28, the life and anthropological ideas of Margaret Mead being the apparent source of inspiration for King. Among other things, Smith admires King's "restrained prose and eagerness to dissect not just the emotional but the intellectual bonds among her protagonists as they improvise their way in a nascent discipline without established methodologies or theoretical models". Does it stop short, I wonder, of that specialized redoubt where ideas are made to speak louder than characters?

February 6, 2015

'The French Intifada'

Courneuve, to the north of Paris described by Andrew Hussey as "run-down and dangerous" JACQUES DEMARTHON/AFP/Getty Images

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

In his excellent book The French Intifada: The long war between France and its Arabs (2014), Andrew Hussey opens with a discussion of the concept of the banlieues: “For all their modernity, these urban spaces are designed almost like vast prison camps. The banlieue is the most literal representation of ‘otherness’ – the otherness of exclusion, of the repressed, of the fearful and despised – all kept physically and culturally away from the mainstream of French ‘civilization’”.

Ok, the quotes around the word civilization were perhaps unnecessary – after all, we can see where Hussey is coming from. Yet it does bring to mind the phrase “mission civilisatrice”, the nineteenth-century notion, promulgated by the statesman Jules Ferry, that French colonialism was in part a quest to bring Western, specifically French, values, culture and ideas to “backward” peoples, mainly in West Africa and what the French refer to as le Maghreb, i.e. Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia (which, I learn from Hussey’s book, had a “thriving Jewish community of some 100,000” before the German occupation of 1942).

Hussey goes on to say that “the banlieues are made up of a population of more than a million immigrants, mostly but not exclusively from North and sub-Saharan Africa. As the population of Paris has fallen in the early twenty-first century, so the population of the banlieues is growing so fast that it will soon outnumber the 2 million of so inhabitants of central Paris”. A staggering thought.

This pattern can probably be replicated in other big cities such as Lyon, and Marseille, as well as in the smaller cities (Roubaix in the far north, for example, which is also the poorest town in France, has a large Muslim population). Of the banlieues of Lyon Hussey writes: “. . . the people who live there are angry and unhappy”, living “in a kind of spiritual poverty . . . because they do not belong here. No one does”. When riots erupted across the country in the autumn of 2005, the Interior Minister Nicolas Sarkozy talked of the need to hose down “la racaille” (scum), the kind of language that could quite conceivably have forced a resignation had he been a British politician; instead, he was voted in as President in 2007, and is now positioning himself for another stab at the presidency in 2017. What price a gruesome run-off between Sarkozy and the Front National leader Marine Le Pen in two years’ time?

But for most of us visitors to France it’s probably safe to say the banlieues are merely glimpsed from the window of a Eurostar train speeding into the Gare du Nord, or of a shuttle service from Charles de Gaulle airport. Even in Marseille they are not immediately visible. Which prompts the question: how much of the real France are we seeing as we breeze in and out again?

As Natasha Lehrer wrote in her TLS review of Hussey’s book (August 1, 2014), the author “combines the job of a historian with that of a reporter and he evinced a gusto for being on the ground” – not just in the “Hexagon” but in Algiers (lyrically described), Tangier, Casablanca, Marrakesh and Tunis. Hussey provides an excellent background history of France’s colonial involvements in North Africa, from the first arrivals in Algeria in 1830 to that country’s independence in 1962. It doesn’t make for pretty reading: for every enlightened colonial administrator like Marshal Hubert Lyautey in Morocco there was a Paul Aussaresses, a brutal captain in the Special Operations Unit in Algeria during the war of independence.

Algeria was more closely integrated with France than either of its neighbours, becoming “as French as Alsace-Lorraine, Provence or Brittany”, in Hussey’s words – hence in large part the particularly violent nature of its decoupling, with atrocities being committed on both sides, as Hussey reminds us in grim detail (he draws effectively on Alistair Horne’s still essential A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962, published in 1977.) But it was a war that no one came out of unscathed: even Albert Camus, on a visit to Algiers in 1956, was denounced for referring to “Arabs” rather than “Algerians”, perhaps unwittingly revealing how far removed from the realities on the ground he had become in his self-imposed Parisian exile.

On a trip to Tunis in 2012, Hussey describes an encounter with “a guy called Omar”: “I asked how he felt about the revolution. ‘We thought that the Europeans would help us, that the French would give us money and aid. But instead they insult us.’ (He was referring to the Charlie Hebdo cartoon.)” How significant that comment now seems.

Nothing can of course justify last month’s appalling acts, but if there is a link between extreme social deprivation, crime and Islamist radicalization, here’s a fact from Hussey’s diligent researches that might be of some relevance: “At the latest estimate, the prison population of France is thought to be 70 per cent Muslim. No one can know the exact figure because under French law it is illegal to distinguish individuals on the grounds of their religion – this is the principle of laïcité, the specifically anti-religious concept which is supposed to guarantee the moral unity of the French nation”.

In an article in Le Monde a few days ago, part of an in-depth investigation into the backgrounds of the killers, the paper's reporters Jacques Follorou, Simon Piel and Matthieu Suc focused on the scale of Islamist radicalization taking place in French prisons: it happened to Amedy Coulibaly, the gunman at the Jewish Hyper Cacher supermarket in Vincennes, who was once an inmate of Europe’s largest prison, Fleury-Mérogis, to the south of Paris. Also radicalized in prison were Khaled Kelkal, one of those responsible for the 1995 attacks on the Métro system in Paris in which eight people were killed; Mohamed Merah, who went on the rampage in Toulouse in 2012, killing both Jewish primary schoolchildren and French soldiers of North African origin (harki, the term for Algerians who fought on the French side in the war of independence, is a grave insult among Arab youth today – were Merah’s victims viewed as harkis?); and Mehdi Nemmouche, last year’s assailant on the Jewish Museum in Brussels. As if to demonstrate the problems faced by the authorities, the journalists reveal that radicalized inmates employ a tactic called taqiya, which consists of hiding one's faith so as not to come into conflict with those very authorities.

In the midst of the soul-searching and attempts on the part of the French to understand how they have come to be where they are, it will be of no consolation to read Hussey’s conclusion:

“In the nineteenth century, Charles Baudelaire wrote of Paris being haunted by its past, by ‘ghosts in daylight’. In the early twenty-first century, the ghosts of colonial and anti-colonial assassins continue to be visible in the daylight of the banlieues. It may be that what France needs is not hard-headed political solutions, or even psychiatry, but an exorcist.”

February 5, 2015

Harper Lee: happy as hell

1961- Photo by Donald Uhrbrock//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

By ROZ DINEEN

“To Kill A Mockingbird comes from America laden with well-deserved praise” – this from the TLS of Friday October 28, 1960. “In situation and tone it has something in common with The Member of the Wedding though its development and atmosphere are more commonplace . . . the message [is] one that can stand repetition . . . ”.

A Pulitzer prize, about 40 million copies, countless exams papers and fifty-five years later, at Penguin Random House on a Tuesday afternoon, “A series of screams went up around the office”. Excited staff members having just heard that their company has acquired the UK and Commonwealth rights to Harper Lee’s next book, Go Set a Watchman.

The “new” novel was written in the 50s, before To Kill a Mockingbird; it features the same characters twenty years on. Lee thought she had lost it. Her lawyer found it “affixed to an original typescript of To Kill a Mockingbird.” Screams.

All this is just a bit surprising in terms of literary biography. Lee is known as the recluse, who stopped talking to press in 1965 after finding the media attention surrounding Mockingbird overwhelming. The New York Times reported last year, “To those who chase her, who can’t leave well enough alone, she has developed a standard response to their proposed interviews: ‘Not just no, but hell no.’”

“It’s better to be silent,” she once told an audience, “than to be a fool.”

Gossip whirs. Her friend and lawyer Tonja Carter, who found the manuscript, is mentioned in reports along with the ill-defined smell of something funny going on here. Is Lee being used, or coerced? Since a stroke in 2007 she has become progressively blind and deaf. Her sister Alice, a lawyer who helped her manage her affairs, not to mention her considerable annual royalties, died in November. Alice wrote in 2011: "Harper can't see and can't hear and will sign anything put before her by anyone in whom she has confidence".

In recent years Lee has brought charges against her former agent, Samuel Pinkus, claiming that in 2007 he "duped" her into assigning him the copyright to Mockingbird. In January 2012, Tonja Carter attempted to force Pinkus to assign the copyright back to Lee, which he did in April. Vanity Fair reported that, "Carter obtained power of attorney over Lee and fired Pinkus".

Meanwhile Lee's agent David Van Dusen said in an interview with Vulture earlier this week that: "she’s very deaf and going blind. So it’s difficult to give her a phone call, you know? I think we do all our dealing through her lawyer, Tonja. It’s easier for the lawyer to go see her in the nursing home and say HarperCollins would like to do this and do that and get her permission. That’s the only reason nobody’s in touch with her. I’m told it’s very difficult to talk to her". Yet he denied that she was a "recluse".

Today we hear, presumably through Carter, that she is “alive and kicking and happy as hell”.

But, hell, isn’t it exhausting to always worry so much about what our great writers ate, and how they slept, and how and by whom they are used? What about the book?

In a statement Lee has said of Go Set a Watchman that “My editor [in the 50s], who was taken by the flashbacks to Scout’s childhood [in it], persuaded me to write a novel from the point of view of the young Scout. I was a first-time writer, so I did as I was told.” The result was Mockingbird. Van Dusen puts it like this: "her editor at the time at Lippincott, said to her this isn’t what you want to write; you want to write something about Scout when she was a girl". You might say, then, that Go Set a Watchman was rejected. Lee was asked to improve on it.

And yet this apparently unedited book will be, according to Waterstones, "the most sure-fire hit of the century”.

Lee gave a rare interview to Roy Newquist back in 1964 in which she spoke of her hopes and plans:

“Well, my objectives are very limited. I want to do the best I can with the talent God gave me. I hope to goodness that every novel I do gets better and better, not worse and worse. I would like, however, to do one thing, and I’ve never spoken much about it because it’s such a personal thing. I would like to leave some record of the kind of life that existed in a very small world. I hope to do this in several novels – to chronicle something that seems to be very quickly going down the drain. This is small-town middle-class southern life as opposed to the Gothic, as opposed to Tobacco Road, as opposed to plantation life . . . . In other words all I want to be is the Jane Austen of south Alabama.”

Here is a sadness. Either Go Set a Watchman is dismissed and Lee loses her moniker — literature's greatest one-hit wonder; or Go Set a Watchman stands up to and matches Mockingbird, then we will miss these apparently unwritten or unfinished accounts of Southern life all the more. Unless, of course, there are yet more manuscripts to find, and Lee, no-longer reclusive, but “alive and kicking and happy as hell” will pull them into the light. Screams.

February 4, 2015

No More, Mr Nice Guy?

By MICHAEL CAINES

Here’s one corollary of that well-worn maxim about victors writing history: historians love a villain. And, you might add, so do novelists. For example: out of her memories of a Catholic schooling at Harrytown Convent near Stockport in Cheshire, Hilary Mantel has taken the sainted image of Thomas More (he was canonized in 1935) and turned him into the arrogant, fundamentalist, torture-condoning prig of Wolf Hall. A Man for All Seasons, as many have noted, this is not. Is it fair to make More so foul?

I've been dawdling around the middle ground between history and fiction recently, trying to size up the "real" More from a biographical angle, so I’m finding it interesting to see not only how he appears in the BBC2 adaptation of Wolf Hall (the third episode of which airs tonight), but also how this fictional More has alarmed those with some expertise on the historical subject – in the same way that the abysmal Anonymous caused consternation among Shakespeare scholars, or Becoming Jane bemused some Austenites. These were cinematic fictions, yes, but they derived from facts; the fear was that they would lead others to think that they had some claim on the exciting, secret truth of the matter.

At least, that seems to be one justification for rising up and whinging about the Hollywood version of history. The assumption seems to be that cinema-goers are wonderfully suggestible, as must be viewers of Wolf Hall. (And readers of the novel? Here's my review from 2009.) If that's true, they have learnt by now that Thomas More (played with bedraggled pomp by Anton Lesser) was just some grandee with a nice line in schoolteacherly hypocrisy. “Oh, I think it’s a little late to read the Cardinal a lesson in humility”, he can intone of Cardinal Wolsey, as that churchman falls from favour and More, the lawyer, rises.

To Thomas Cromwell (played by Mark Rylance), this is good coming from More, lording it over a politicos’ dinner party (Cromwell has to number among them to engage in this conversation at all, of course, but don’t worry, he arrives late and sits at the far end of the table). More boasts of his piety, but here he is usurping Wolsey’s position as Lord Chancellor. “What’s that, a fucking accident?”, Cromwell asks, prompting More to exit in a curmudgeonly grump. This is a far cry from the quick wit whose company the King supposedly enjoyed so much that More could barely excuse himself to go home and see his family.

Something tells me this television serial may be an attempt to create a costume drama out of a less-than-telegenic crisis. While Henry VIII (played by Damien Lewis) strides purposefully through rooms of lackeys or stands with arms akimbo to correspond with our imaginary portraits of him, a few loyal subjects are presumably just out of shot hacking out the terms of a trade agreement with Charles of Castile, or counting the Church revenues over which Cromwell and Anne Boleyn are to disagree. More himself complained about not seeing enough of his family thanks not just to a good stock of witticisms but the arduous hours the administration of the King’s affairs compelled him to keep. And no doubt there would be some difficulty in conveying over dinner, in Peter Straughan’s dialogue, that the hair-shirt More was wearing under his finer robes was itching somewhat.

I guess More’s big moment on the box/block is still to come, as his own fall from power approaches. Yet it’s striking to see how, of all the wrong notes to pick out, it’s perhaps this – the Mantel version of a man dubiously accorded the honour, in 2000, of being appointed Rome’s patron saint of politicians – that has already caused the most fervent outcry. David Starkey has had his cake (Wolf Hall is a “wonderful, magnificent fiction . . .”) and eaten it (it is “based on a deliberate perversion of fact”); Jonathan Jones has eloquently summarized the defence against the Mantel “caricature”; and two Catholic bishops have made their opinions known, too, apparently unaware that they are simply inviting undercutting remarks along classic Mandy Rice-Davies lines, that – well, they would say that, wouldn’t they?

More’s legacy has always been a doubtful and controversial one, from the time of his execution, through Shakespeare’s use of his Richard III (More knew what it was like to be a historian in search of a villain), to the socialist acclaim for Utopia, and down to our own revisionist accounts, in which he may appear to be, in the words of Jasper Ridley, “a particularly nasty sado-masochistic pervert”. Some believe Mantel has made a villain of a hero, or even stolen some of More’s thunder and given it to her own protagonist, Thomas Cromwell (you could write a whole book, and indeed John Guy has, about the mutual adoration of More and his daughter Margaret; here it is Cromwell who is kind to animals, a man of strong family feeling etc).

"It is not a battle between history and fiction", Diarmaid MacCulloch has said, "It is a conversation." (Do Professor MacCulloch's fellow conversationalists know that?) Or to put it another way: the current counter-movement to Wolf Hall is just the latest variation on a sometimes acrimonious and oft-aired theme. What next for the humanist scholar who seems to have played so many roles in his own life – lawyer, London undersheriff, family man, pursuer of heretics, Lord Chancellor, martyr – what role will be thrust on him next?

January 29, 2015

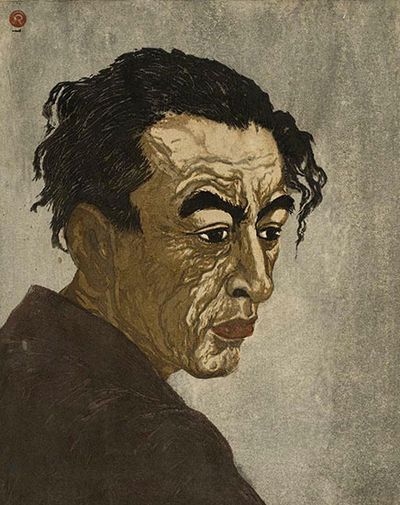

Sakutarō Hagiwara, ‘big cheese’

Portait of Sakuturo Hagiwara, 1943, by Onchi Koshiro

By THEA LENARDUZZI

This may not be as audacious as my colleague’s recent blogs, but I have a confession – quite a weighty one for someone who reckons they’ve got a grip on Modernism’s many modernisms (well, as much as one can). I’ve never read Sakutarō Hagiwara. Not a word, in fact. Thankfully NYRB Books have come to my rescue with a slim anthology of his poems in new and revised translations by Hiroaki Sato. Hagiwara is, so the blurb tells me, “the big cheese”, and Sato, “the master translator” (a cracker, you could say).

Cat Town is necessarily slim – Hagiwara died in 1942 at the age of fifty-five from a combination of lung cancer, pneumonia and alcoholism, compounded by life-long mental afflictions. The poems here are drawn from his two main collections (Howling Moon, 1917, and Blue Cat, 1923), bolstered by Sato’s excellent introduction, Hagiwara’s original prefaces from both, and a generous selection of verse from across his career. Sato’s edition takes its title from Hagiwara’s “roman in the style of a prose poem” (Hagiwara’s phrase; he took issue, as Sato explains, with the standalone term “prose poem”), which appeared as an illustrated volume in 1935.

Hagiwara was an over-indulged first son, born in 1886 to a respectable but dysfunctional Japanese family in Maebashi, about 115km north-east from Tokyo. He yearned for the metropolis until he dropped out of college and moved there in 1911 – in part, to learn the mandolin, with the intention of becoming a professional musician. “As far as academic matters go, it is an irony not infrequent in the world of literature that Hagiwara, who would go on to become one of the most important poets in Japan, continued to fail Japanese language class”, notes Sato, whose potted biography carries us through Hagiwara’s first encounters and experimentations with the 5-7-5-7-7-syllable tanka form (as well as haiku and kanshi verse), and on to his embrace of the radical, colloquial free-verse style which made his name, at home and abroad.

Hagiwara’s relationship with poetry was not an easy one. There were times when he shunned the medium entirely in favour of prose, publishing collections of essays and “aphorisms” (as he called them); these became increasingly autobiographical – generally despairingly so, as you might expect from a man who enjoyed reading Nietzsche and Schopenhauer – with titles such as Turning Back to Japan (which, of course, implies an earlier turning away from it) in 1938, The Man Who Came Home and Idiot, both published in 1940. (Sato works in a few quotations to cherish from Hagiwara’s contemporaries, such as this one from Hinatsu Kōnosuke: “Hagiwara has no literary training, that’s the fellow’s strength more than anything else”.)

No doubt in part because of the mandolin years, Sato explains that there is “a presumption made upon approaching Hagiwara’s poetry that it is ‘musical’” – indeed, for the poet Murō Saisei, Hagawari “turned the Japanese syllables into [piano] keys”. This equation between music and language irked Hagawari (he warned against the “common folly” of blurring the distinction between tuneful verse and music). The musical quality of his poetry was nonetheless emphasized in early English translations by Donald Keene and Graeme Wilson (who is perhaps best known for his translations of Natsume Sōseki).

Quoting Hagiwara, Sato writes: “Poetry was a ‘direct expression of music’ only when the poet succeeded in projecting his inner rhythm, namely, his vision”. Without intense and precise “sentiment” which came in the form of the “image”, Hagiwara’s poems might simply have been pretty word-melodies.

One of Graeme Wilson’s early translations of the poet appeared in the TLS in February 1967. Though the end rhymes might lack the subtlety and intuition of Sato’s more recent efforts, I think it holds up quite well:

In the Mountains

October at the fading of the year,

Waits for my prayers and silences.

The birds and fishes disappear

Into their fasting distances

And autumn flowers fade. Their colours seep

To lend the whitening air an opal shine.

Nothing, not even prayer, dare run too deep.

Touch but a Bible, it turns argentine.

Sato hasn't translated this one afresh, so perhaps we’re in agreement.

January 27, 2015

The novel of oh dears

By MICHAEL CAINES

Well . . . what have I learned recently? That poetry is a medieval form of unreason and that some sui generis prose writers could win prizes for intellectual complacency – or hang on, is it the other way round? Either way, I've offended someone.

There is little to learn from such encounters, unfortunately, but I've enjoyed the predictability with which some have received my observations about, first, a storm-in-a-teacup literary prize, and then a novelist's revealing use of a single word. I suppose I should be looking around for a dramatist to offend. And I am going to see The Hard Problem soon . . .

But to stick with novels for now, here's something to look forward to: it's almost time for the LSE Space for Thought Literary Festival, which is now in its seventh year. . . .

On both occasions when I've chaired Space for Thought panel discussions in the past – on parody in 2013, and The Grapes of Wrath last year – the speakers were excellent, the audience engaged and articulate. It was everything the average episode of Question Time now isn't. So I'm looking forward to this year's festival, which has the appropriate theme of "Foundations" for LSE's 120th anniversary, and especially to chairing this panel on February 28: Is there life in the "novel of ideas"? In the words of the festival programme: is the novel of ideas enjoying a "resurgence", or is it "an outdated genre"?

There has certainly been plenty of helpful discussion about the novel of ideas online in recent times, as in this Online Literature thread and these recommendations from Rebecca Goldstein. But can you name a book published in the past year that you would confidently describe as a "novel of ideas"? And another initial piece of devilish advocacy on the subject: as far as this part of the Anglo-Saxon world is concerned, does it even exist?

I'd like to think I know what is generally meant by the term – or at least I would reckon Diary of a Seducer, Sartor Resartus, Middlemarch, The Man without Qualities, The Moviegoer and Infinite Jest are among the most frequently cited examples – but oddly it doesn't appear in the Oxford Companion to English Literature, nor the equivalent volumes from Cambridge, Bloomsbury etc. It's a different story in France and the US, I'm told. Why the lack of acknowledgement here?

I guess I'm looking in the wrong places, but expect the speakers on Feb 28 will have an answer or two to these (and, I hope, less crude) questions: Professor Peter Boxall, the author of Twenty-First Century Fiction: A critical introduction and a forthcoming book called "The Value of the Novel"; Jennie Erdal, the author of Ghosting and a deeply entertaining novel, The Missing Shade of Blue: A philosophical adventure; and the novelist Andrew O'Hagan, whose new book The Illuminations I'm reading with great pleasure at the moment.

As ever, it would be very good to see a few TLS readers there (and maybe I'll see you at John Gray's talk about human freedom or what sounds like a very promising discussion about music and poetry). I hope to come back to the subject of the novel of ideas between now and the LSE festival on this blog, between blithe attempts at poking ant-hills with a long stick. . . .

January 22, 2015

Robert Herrick and John Evelyn: Minority reports

By MICHAEL CAINES

As Paul Davis pointed out in last week's TLS, seventeenth-century poetry is full of small things: Andrew Marvell's "little globe" (a drop of dew); Edmund Waller's lovely ribbon binding a "slender waist"; and, above all, the "nano-phenomena" that caught the eye of Robert Herrick. Davis's review ("Maximum Parsimony", for subscribers only) brought home the conflict of scale in the sole collection of verse Herrick published in his lifetime: Hesperides is stuffed with 1,400 lyric pieces but barely "three dozen or so" are more than fifty lines long.

I've selected a few examples of this copious miniaturism to read for this week's episode of the TLS podcast, TLS Voices. And, as we're between seventeenth-century poets in the paper itself, here's a reading of a longer poem, too, by a poet who, you might say, is both more and less famous than Herrick: John Evelyn, whose Diary, rather than his poetry, is the cause of his enduring literary reputation. In fact Evelyn the poet will be known to very few readers, and his contemporaries would have known him instead for his other intellectual interests, and his activities as a member of the Royal Society. Yet he wrote poetry throughout his life, and when his daughter Mary died in 1685, he expressed his sorrow in the elegy recorded here. "On My Dear Child M. E." will also appear in full in next week's issue, alongside Stuart Gillespie's fascinating account of Evelyn as poet rather than diarist.

January 21, 2015

Medieval Salman Rushdie

"We", whoever that is, all know what the Middle Ages were like, don't "we"? They were nasty, brutish, and went on for ages. Anything after the Romans and before the Renaissance is the bad old Middle, right? You could call it "medieval"; everything smelled bad, minds and bodies were in a permanent state of plague, and the only known form of entertainment was killing, in all its most disgusting forms. See above for an expert reconstruction of what the world used to be like.

If you believe all this, and don't believe in the existence of cathedrals and Chaucer, congratulations – to borrow the words of Joseph Brodsky, "you're in The Empire, friend" – the empire of intellectual complacency. Or you've just mistaken Monty Python and the Holy Grail for real life. Medievalists – those who study the art and architecture, the literature, the politics and philosophy of this period, and therefore have a vested interest in arguing, quite bizarrely, that there may be more to it than that – will roll their eyes at you, but don't mind them. Let Salman Rushdie show you the way. . .

In print, commentary on the horror of the Charlie Hebdo murders must already run to a library's worth of heavy bound volumes. From Rushdie came this statement, which strains to earn a volume to itself. The first sentence of it runs:

"Religion, a mediaeval [sic] form of unreason, when combined with modern weaponry becomes a real threat to our freedoms."

As others have noticed (and yes, I've only just noticed that others have noticed), whatever one thinks of the rest of this opening line, its third word is a disputable choice, even one some people are willing to dispute amid the furious agreement and disagreement about what Rushdie goes on to say about "religious fundamentalism" and satire. (Not that Rushdie is alone in his misconception of what "medieval" means. I particularly like this comment on his comment, from the Wall Street Journal's Speakeasy blog: "Religion is not a mediaeval form of unreason. Not reasoning well is mediaeval . . .".)

I was reminded that there's more than pedantry to the unthinking use of "medieval" as a pejorative at a superb colloquiuum I attended last autumn, at Queen Mary, University of London; the delegates were mainly postgraduate students and academics at an early stage in their career, and they were there to consider the question of public engagement – what "impact" could medieval studies have in print or on the radio? Their career prospects aside, it was obvious that running into the common assumption that they wre devoting their lives to the study of an era of "unreason" might be slightly irksome to them. I wonder what they would say now a well-known novelist has suggested that "religion, a medieval form of unreason" – that's "religion" as in Benedictine monks and "unreason" as in the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, then – is more or less on a continuum with death by assault rifle, as appallingly seen in Paris on January 7, 2015.

While some pundits have criticized Rushdie for, say, equating "religion" with "fanaticism", a lot of people seem to have approved of his statement; and I can see why belatedly picking up on a seemingly minor verbal slip might seem irredeemably trivial. (But isn't the devil said to have a fondness for such minutiae?)

I wonder if more of the pundits would have noticed if religion had been described here as an ancient or even just a contemporary form of unreason (ah, those irrational theologians!). A historian might observe, too, that we owe more to those unwashed ancestors of ours than we care to acknowledge; even the not widely loved period between AD 400 and 700 remains "central to the modern European sense of identity", as Nicholas Vincent wrote in the TLS last summer. And years ago, a medievalist told me how weird and exasperating it was to see the word "medieval" constantly being deployed as a colloquialism that, quite childishly, just meant: all the bad things that are nothing to do with modernity. I said I wasn't sure; it sounded like the proverbial storm in a teacup. It's just a figure of speech, the historian admitted – conversation loves a cliché, you know – but isn't it a revealing one? Indeed, everybody can see what Rushdie was trying to say. "Medieval" means "pre-rationality, brutality and theocracy", OK?

Recently published books on subjects such as the refashioning of "archaic language" in the early seventeenth century and "comic medievalism" (to be reviewed in the TLS in the near future) invite the same sort of question. Why is it that "we" associate the worst of our own world and our own time with the long-gone past, and with people who aren't around to answer back?

Perhaps the answer is here, courtesy of The Conversation:

"First deployed in the Renaissance, the term 'medieval' was invented by scholars who wanted to celebrate the progress of their own age in contrast to the preceding centuries. Describing something as medieval has since endured as a successful form of negative branding."

In other words, by using this particular adjective, Rushdie is repeating one of the hoariest of rhetorical tricks, an exercise in "negative branding" as old as the writings of fifteenth-century historians such as Leonardo Bruni (but also, I am told, with considerably older roots; which means that one day perhaps it will be possible to speak of the "medieval Salman Rushdie"). To those in power, at any rate, its power remains undimmed – whichever side they're on.

If only the novelist had edited his statement so it read, more plainly, "unreason combined with weaponry is a threat to our freedoms". And since the world will never be free of "unreason", "weaponry is a threat to our freedoms" would do just as well. And while he's about it, he might as well drop "to our freedoms", which has a rather grandstanding ring to it. Weaponry is a threat. Then as now. Only some people don't like to admit as much. O tempora o mores, as a thirteenth-century lawyer might have said.

January 20, 2015

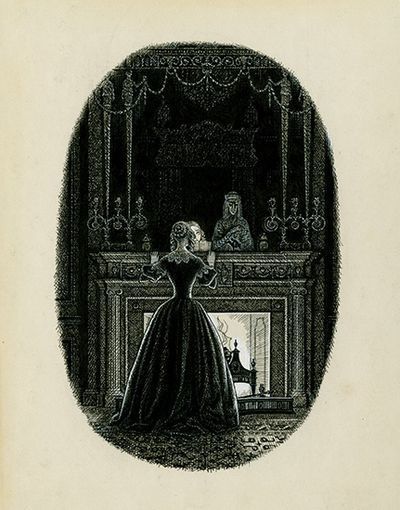

How to illustrate a story

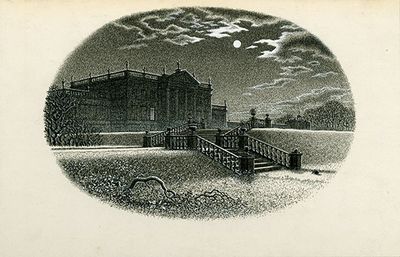

Charles Stewart's frontispiece, 1947, of Uncle Silas. Pen and ink. Courtesy of Royal Academy of Arts, copyright estate of the artist.

Charles Stewart's frontispiece, 1947, of Uncle Silas. Pen and ink. Courtesy of Royal Academy of Arts, copyright estate of the artist.

By MIKA ROSS-SOUTHALL

Editors be warned: there are fastidious rules when it comes to republishing the work of Mervyn Peake. Speaking at the Royal Academy of Arts yesterday on how artists illustrate stories, Sue Bradbury (the former editorial director of the Folio Society), told us that when it came to reissuing his books in 1999, Peake's estate wouldn't allow illustrations of figures. Halls, buildings and landscapes were acceptable, but no “characters”. In the words of the Folio Society's founder, Charles Ede, the relationship between the author, illustrator and publisher is like “a ménage à trois conducted on tight-ropes”.

Should artists choose which parts of a text they want to illustrate, or should the author (even if dead) direct them? And how much control do the publishers have?

A new one-room exhibition at the RA showcases the intimate, creative processes and working methods of a commercial twentieth-century book illustrator, Charles Stewart (1915–2001). He was fascinated by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s gothic novel Uncle Silas (1864) and created his own visual world for the book in the late 1940s. It was well received by the Bodley Head, but Stewart’s intricate pen and ink drawings – a pastiche of the steel etchings and wood engravings by Victorian illustrators such as Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne) and George Cruikshank – were his own downfall. In an article, Stewart said:

“My aim was to try to convey the feeling of the [book’s] period by studying the style and conventions of the illustrators of that time . . . . Unfortunately, my pen work, known to my friends as my knitting, was so close in texture that it proved impossible to reproduce satisfactorily by the usual line block process”.

Charles Stewart, "The figure of Uncle Silas rose up, with a death like scowl", undated. Pen and ink. Courtesy of Royal Academy of Arts, copyright estate of the artist

Charles Stewart, "The figure of Uncle Silas rose up, with a death like scowl", undated. Pen and ink. Courtesy of Royal Academy of Arts, copyright estate of the artist

The publishers couldn’t afford the expense after the Second World War and abandoned the project. Almost forty years later, however, Stewart showed his illustrations to Bradbury, who immediately commissioned a further twenty-six decorations and tail-pieces, as well as a design for the binding, to accompany his thirty original illustrations. The Folio Society finally published Uncle Silas in 1988 (and they’ll be re-printing the same edition this summer).

A selection of strange objects – discovered in the artist’s studio by the curator Amanda Doran – are arranged in one of the exhibition’s display cabinets. Included are a pair of black ballet shoes bought at “Charing Cross Road, London, c.1960”; a wooden box of glass eyes (three blue, one brown) bought on “Portobello Road, c.1956”; and a Penguin Classics edition of Uncle Silas with Stewart’s annotations on the dust jacket. Under Le Fanu’s name, the cover should read: “Specially edited by Christine Longford”; Stewart’s version reads: “Specially edited, abridged & practically rewritten by Christine Longford (may the Devil turn her black)”. An array of bird and human skulls, quirky puppets and a huge collection of historic costumes and mannequins, on which to display the clothes, were also found by Doran, though they’re not on show here. Instead we see Stewart’s extensive preparatory sketches – often made from these items – alongside their realizations in print. “Usually more is less”, Bradbury said, “but in Stewart’s case, his amount of detail and accuracy manage to be haunting.”

His illustrations communicate an atmosphere or psychological state, often the result of meticulous research, but also informed by a dalliance in professional ballet dancing. While training to be a draughtsman at the Byam Shaw School of Drawing and Painting, Stewart performed at Glyndebourne in 1936 in Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, and then joined the corps de ballet at Covent Garden in 1936–7 for Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffman and Verdi’s Aida. It gave him a valuable understanding of staging and set-design.

Interiors and architecture are pivotal to the novel. The narrator, Maud Ruthyn, is locked away from society in ancient mansions, first by her father, and then, after his death, by her Uncle Silas, who is shrouded in rumours of immorality, murder and drug addiction. Stewart sketched country estates and used old copies of Country Life for details of staircases, chimney pieces, furniture and furnishings: “Knowl and Batram-Haugh, the two great houses in which the story takes place, became so real to me that I drew plans of the principal rooms, choosing and placing the furniture so that in imagination I could move about them freely”.

Charles Stewart, "Meanwhile, the winter deepened", 1947. Pen and ink. Courtesy of Royal Academy of Arts, copyright estate of the artist

Charles Stewart, "Meanwhile, the winter deepened", 1947. Pen and ink. Courtesy of Royal Academy of Arts, copyright estate of the artist

A simple line from the text, “Meanwhile, the winter deepened", was transformed into an illustration (above) of an imposing house in the moonlight, with an ominous, leafless tree fallen in the foreground. Another of my favourites – “She stood scowling into the room with a searching and pallid scrutiny” – depicts Madame de la Rougierre, the nasty French governess, with a skeletal face, brandishing a candle towards us in a doorway. The chiaroscuro is striking. Similar to that of the film adaptation of the novel, already underway while Stewart was making his illustrations. He visited the set at least ten times in 1946 to sketch portraits of the actors. He collected many of the film stills – some of which are in the RA's exhibition. It’s difficult to gauge how much Robert Krasker’s bold cinematography (also seen in The Third Man and Brief Encounter) influenced Stewart’s final work, and vice versa.

Having dabbled in illustration myself, I’d hazard to say that any book can be illustrated – on film, paper or otherwise – even the less obvious ones, such as Finnegans Wake. (Indeed, the Folio Society recently published an edition.) Maybe Joyce left behind a few guidelines . . . .

January 16, 2015

In the Almanach de Gotha

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

The great French painter Nicolas de Staël (1914–55), when asked about his family antecedents, was said to casually reply “Have a look at the Gotha”. He was referring to the Almanach de Gotha, the directory of European aristocracy.

The Staëls emerged from Holstein in Germany, from where they migrated via Sweden to St Petersburg. The painter’s father was vice-governor of the Peter and Paul Fortress in St Petersburg at the time of the Revolution, and the family was forced to flee Russia in 1919, when Nicolas was five years old. Nicolas spent part of his childhood in Belgium before moving to Paris in his twenties, where he more or less settled (“settling” being a relative concept in his restless life, which might explain why Staël only took out French citizenship relatively late in his short life). His centenary was marked by two exhibitions in France last year.

The family of another Russian exile, Nicholas Romanov, followed a similar trajectory: they too fled the country in 1919. Nicholas was born in 1922 in Cap d’Antibes (which, coincidentally, was where Staël committed suicide at the age of forty-one) in the South of France, and died in September last year. His father Prince Roman Petrovich of Russia was cousin to Tsar Nicholas II. Nicholas Romanov was, according to his obituary in the Times, “the stateless head of Russia’s former ruling family”, and a republican.

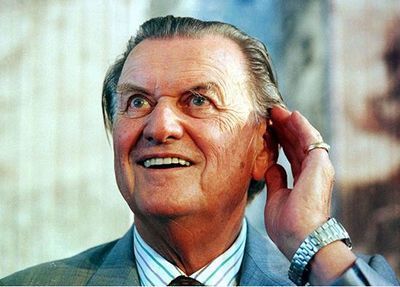

Nicholas Romanov – Lehtikuva Oy/Rex Features

Nicholas Romanov can, of course, be found in the 2014 (and 191st) edition of the Almanach de Gotha, under “Russia (House of Romanov/Romanoff)”. He was resident in Livorno, Italy. According to the Times obit, Romanov hosted the launch of the 2003 Almanach in London, when “he was at pains to point out that admittance to its pages was not a foregone conclusion. ‘Southern Italy is full of dukes . . . Very nice families, but there are millions of them. And the Almanach has always been careful with Portuguese dukes’”.

There can be no such doubts about the Duchess of Alba, who was born in 1926 and died last November. The Times, again, referred to her “unmatched collection of titles, fabulous wealth and colourful love life” as well as calling her “one of Europe’s most eccentric aristocrats”. She was a “descendant of King James II”: “had the . . . Scottish referendum ended differently, her connection to the Stuart dynasty would have given her a claim to the Scottish throne”. Apparently “she owned so many estates that it was said she could travel from the northernmost point of Spain down to the south coast without ever stepping off her own land”.

There she is on p153 of Vol II: “Maria del Rosario CAYETANA Paloma Alfonsa Victoria Eugenia Fernanda Teresa Francisca de Paula Lourdes Antonia Josefa Fausta Rita Castor Dorotea Santa Esperanza Fitz-James Stuart y de Silva, 11TH DUCHESS OF BERWICK, 18TH DUCHESS OF ALBA DE TORMES, Almazán, Liria and Jérica, Aliaga, Arjona, Hijar, Jerica, Montoro, Countess and Duchess of Olivares, Marchioness of the Carpio, San Vicente del Barco, La Algaba, Almenara, Barcarrota, Castañeda, Coria, Eliche, Mirallo, Mota, Moya, Orani, Osera, San Leonardo, Sarria, Tarazona, Valdunquillo, Villanueva del Fresno, Villanueva del Río, Countess of Aranda, Lemos, Lerín, Miranda del Castañar, Monterrey, Osorno, Palma del Río, Salvatierra, Siruela, Andrade, Ayala, Casarrubios del Monte, Fuentes de Valdepero, Fuentidueña, Galvi, Gelves, Guimerá, Modica, Ribadeo, San Esteban de Gormaz, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Tinmouth, Villalba, Viscountess of la Calzada, Baroness of Bosworth, Lady of Moguer, Grandee of Spain 1st Cl.”

Prince David Chavchavadze (who also died in November 2014), meanwhile, was descended from both the Russian and (as his surname suggests) Georgian royal houses and ended up working for the fledgling CIA after the war. He seems to have been a particularly colourful character (the photo accompanying the Times obit shows him in what looks like traditional Georgian warrior dress in 1999) who “performed [Russian folk tunes] professionally” in Washington. The name Chavchavadze (Chav for short, perhaps?) appears in the index, but I can find no David on the relevant page – I’m not yet very adept at consulting the Almanach, clearly.

That’s quite a trio of European royals we've recently lost. And, while on the subject, I learnt from the Almanach that there are ten surviving royal houses in Europe – can you name them? (I should say that I’m neither royalist nor republican, just a fence-sitter who thinks that royals can add to the gaiety of nations.)

The Almanach is a monumental publication, 2,700 closely printed pages spread across two volumes, but I guess it doesn’t have to update to quite the extent of its fellow publication the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, which annually publishes records of hundreds if not thousands of cricket matches played around the world in the preceding year.

Reviewing the last Gotha in the TLS (October 5, 2012 – it’s a long way from being an annual publication), the historian David Gelber wrote of how it “became a handbook for husband-hunters, fortune-seekers, pedants and pretenders”. Yet “its punctilious itemization of titles, lineage and heraldry aims for scholarship rather than sensation”.

I didn’t know the Almanach included a 500-page country-by-country gazetteer. It’s sobering to discover from it that the death penalty is retained in (by my calculations) 100 countries across the world, including Japan – even if the information is occasionally qualified with the phrase “not used since . . .”.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers